A mad scientist regresses a troubled teen into his primal state: a werewolf. AIP’s iconic low-budget horror was the first starring role of Michael Landon. Beneath the cheeky facade, serious themes are explored. 5/10

I Was a Teenage Werewolf. 1957, USA. Directed by Gene Fowler. Written by Herman Cohen, Aben Kandel, Gene Fowler. Starring: Michael Landon, Whit Bissell, Yvonne Lime, Barney Philips, Dawn Richard, Malcolm Atterbury, Ken Miller, Vladimir Sokoloff, Charles Wilcox. Produced by Herman Cohen. IMDb: 5.1/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 4.9/10. Metacritic: N/A.

Tony Rivers (Michael Landon) is a bright but troubled teenager with an anger management problem. We first catch him at his small town high school where he’s gotten into a fistfight with his friend Jimmy (Charles Willcox) over a triviality. Police detective Donovan (Barney Phillips) breaks up the fight and recommends Tony see psychologist Dr. Brandon (Whit Bissell), who specialises in hypnotherapy, in order to straighten himself out. But Tony ain’t seeing no shrink, instead he takes out his gal Arlene Logan (Yvonne Lime) to the nearby party shack where he and his rebellious teen friends drink beer, listen to rock music and play bongo drums. When happy-go-lucky Vic (Ken Miller) pulls a prank on him, Tony snaps and beats him, but when in the heat of his rage he shoves Arlene, he realises he must seek help. The next day, Tony visits Dr. Brandon (Whit Bissell), who assures Tony that within a few hypnotherapy sessions, he will be his “true self”. In reality, Dr. Brandon sees in Tony’s unhinged rage the perfect test subject for his new serum — a serum that he hopes will regress Man into his primitive origins. Considering the title of the film, we can all see where this is going.

1957’s I Was a Teenage Werewolf is a pop culture icon. Produced by Herman Cohen and directed by Gene Fowler for American International Pictures (the home of Roger Corman, among others), the film was one of the first to combine the tropes of the teenage film and the horror movie. While perhaps not the very first, the film’s enormous success spawned a cottage industry of “I Was a Teenage [insert monster]” movies. What made it stand out, especially, was that this was the first time a teenager was turned into a monster, whereas previously teens had largely been the victims in previous films. This fact created some controversy at the time, which, naturally, only added to its box office appeal.

Unlike mythological werewolfs, Tony’s lycanthropy isn’t brought on by moonlight, but can apparently be trigged by anger, distress or loud sounds. His first victim is a friend of his, whom he attacks while walking home after a party. Detective Donovan and the police department hunt a presumed circus animal or wild dog, while Pepe (Vladimir Sokoloff), the Romanian immigrant cleaner at the police station, warns that they are really chasing a werewolf. Meanwhile, Tony’s behaviour at school improves, and he gets a college recommandation from the principal (Louise Lewis). Unfortunately, after seeing the principal, the break bell causes him to transform, and he attacks and kills a schoolmate who is practising gymnastics (Playboy centerfold Dawn Richard) in front of the principal and several of his classmates. While transformed, they recognise his jacket and trousers, before he flees out into the woods.

Using his newfound animal cunning, Tony is able to evade the police search parties (complete with torches), and seeks out Dr. Brandon for help. But Brandon has no thoughts of helping him, but rather gives him a final shot, which will make the transformation permanent. Unfortunately, Brandon has neglected to restrain Tony before he turns. And turn he does — on his master. The Donovan and the police show up, and the film ends in the same tragic way as all these films end. Even down to the closing line that “there are some things man should not meddle in”.

Background & Analysis

The 1950’s was the decade of the teenager. With rising living standards, the emergence of the American middle-class and a change in culture and morals, teens suddenly found themselves with spare time on their hands and money of their own. The new spending potential of teenagers was quickly realised by cafes and ice cream parlors, radio stations and record companies, and not least TV stations, movie studios and movie theatres. But on the same time, the rise of the teenager brought with it social clashes. Teenagers felt they weren’t given agency by adults and society, and were often left between a rock and a hard place in the white picket fence dream of the new middle-class America. The early 50’s saw a sharp rise in juvenile delinquency in the US, and rather than examining the social causes for this increase, politicians took aim at the entertainment industry. A congressional committee in 1954 cracked down on comic books, but also warned Hollywood that the movie industry might be next, unless studios started self-censoring their output.

Nevertheless, teen angst and juvenile delinquency became cash cows for both major studios and low-budget outfits, both in the US and abroad. From Ingmar Bergman’s Summer With Monika (1953) to Warner’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and MGM’ Blackboard Jungle (1955), teenagers misbehaving filled theatre seats. The rock ‘n roll movie was born with Columbia’s Rock Around the Clock in 1956, and the same year AIP tried to replicate its success with Shake, Rattle & Rock!. AIP exec James Nicholson quickly saw the potential in the teen market — according to one survey, 25 percent of all movie-goers in 1956 were between the ages of 15 and 25. In 1956 alone, AIP released Girls in Prison, Hot Rod Girl, Shake, Rattle & Rock! and Runaway Daughters.

Also in 1956, independent producer Herman Cohen produced a crime drama for United Artists called Crimes of Passion, which bombed at the box office. Seeing as he was not going to make any money out of it, he needed another film quickly, and sought out his old friend James Nicholson at AIP with the idea of merging the studio’s two cash cows, the science fiction horror movie and the teenager movie, into a single product. He proposed a werewolf movie. Cohen wrote the script with his long-time collaborator Aben Kandel. In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, Cohen says that he suggested the title “Teenage Werewolf”, and that it was Nicholson who added the “I Was”. In the interview, Cohen denies that the film would have had the working title of “Blood of the Werewolf”, however, according to film historian Bill Warren, there is a notice in a trade paper from before the film’s release marketing it as just that. James Nicholson has claimed that it was his kids that came up with the memorable title. This, writes Warren, is probably true. He has dug up the number 5 issue of Dig magazine, a sort of rival to Mad magazine, which was very popular with adolescents and teens at the time, and which the Nicholson kids probably read. It contains a humorous article with the title “I Was a Teenage Werewolf”.

For his director, Cohen considered Sherman Rose, with whom he had collaborated on other pictures. But according to Cohen, Rose was going through a lot of personal problems, which made him unreliable. So instead he turned to his friend Gene Fowler, an editor with directing ambitions, and gave him his first directing job. Kanden and Cohen wrote the script under the shared pseudonym as “Ralph Thornton”, and according to the Weaver interview, Cohen initially considered producing it under a pseudonym as well, as he thought the film a major step down from his previous movies. However, comedians like Jack Benny and Bob Hope caught wind of the title and started making fun of it in their skits, which led to magazines like Look and LIFE taking an interest in the film. With all the media attention the movie was getting, Cohen realised the movie’s potential and decided to take due credit. For the all-important role of the teenage werewolf, Scott Marlowe was considered, but Cohen says that Michael Landon impressed him and Fowler in the audition. Landon was at the time an unknown, 20 years of age — not quite a teenager, but close enough — who struggled along in Hollywood as a TV guest actor. I Was a Teenage Werewolf was his big screen debut.

I Was a Teenage Werwolf reportedly had a budget of $82,000 and was filmed over the course of two weeks. Cinematography was handled by Joseph LaShelle, who had worked with directors like Otto Preminger and Lewis Milestone. The monster makeup was designed and applied by Philip Scheer, who had worked as a makeup assistant at Universal during the studio’s monster movie heyday. Yvonne Lime, who already had a couple of teen movies under her belt, was cast in her first leading role as the ingenue, and reliable character actors Whit Bissell and Barney Philips in the roles of the mad scientist and the police detective. In something of a casting coup, the role of Theresa, the gymnast attacked by Tony, Cohen cast adult model and actress Dawn Richard. Although he probably had nothing to do with it, or was aware of it when the movie was made, Richard gave the film some notoriety boost when she appeared as the centerfold in the May issue of Playboy magazine, hardly a month before the film’s release.

This film could easily have descended into full-on cheese-fest. Don’t get me wrong, it is still cheesy enough, but the director and the cast all take it seriously, and the script is not without its merits. Using lycanthropy as a metaphor for teenage rage is not exactly original, but it is both clever and well executed. Tony is portrayed as a well-meaning but mixed-up kid, who has lost his mother and is brought up by a father who is not around due to his work (fine work here by actor Malcolm Atterbury). There’s a fridge scene between Tony and his dad which edges close to the kitchen sink realism of Marlon Brando’s early movies. The teenage sexual urges repressed by adults and society are splendidly released in the scene where Tony the werewolf attacks Theresa, who is clad only in her tight-fitting gymnastics uniform. Unfortunately the film ends in the same blunt ways as all these monster movies end, and it is a shame that Cohen and Kandel didn’t bother to follow its theme through to the end, making for a — mildly put — muddled conclusion.

There would have been fertile ground here to examine the relationship between the psychologist as an older mentor/father figure and the young, rebellious teenager, but the script squanders this opportunity by turning Dr. Brandon into an all-out mad scientist. Brandon’s motives for wolfing out Tony are just as ridiculous as those of the mad scientist in The Werewolf (1956, review). Like in the previous film, Brandon argues that the only way to save humanity from itself is to revert it into its most primal state. In The Werewolf, at least, the scientist tried to explain this bonker theory (admittedly with little success), but here, Brandon doesn’t even bother to explain why turning all humans into bloodthirsty predators would be humanity’s salvation. Also, it is never explained why Tony seems to be a descendant of wolves, rather than apes, like the rest of us.

Another problem with the script is the bane of all these teenage movies written by middle-aged men: the party scene. These seem to have been obligatory to all teenage B-movies of the 50’s and 60’s, and they are always excrutiating to watch. Kudos to Cohen & Co for not casting 35-year-olds as teenagers. Here, the entire teen crowd is played by actors aged 20-25. If you squint, it is possible to image at least a few of them as actual high school kids. The scene in which the kids drink root beer, dance and play practical jokes is not the worst of the lot by far, but it goes on for way too long (and why is there always a guy playing bongo drums?). Plus, there is an cringy musical number performed by Ken Miller, singing a song called “Eeenie-Meenie-Miny-Mo”, written by jazz bandleader Jerry Blaine for the film. It is probably supposed to be rock, but is closer to jazz, and is just awful. Not only is the song awful, the music is also out of sync with Miller’s singing.

But on the whole, the film is well directed. Gene Fowler, the former editor, knows how to set up shots and excels in the action scenes. The fight scene of the opening is very dynamic, as is the scene in which Tony attacks Theresa. Another stand-out scene is the one where the werewolf attacks its first victim in the woods. By this time we have not yet seen the werewolf, nor do we see it during the entire episode — we only hear it, and the camera focuses on the victim’s face, as he realises someone is stalking him in the dark, and finally the scene ends with a close-up on him as the werewolf attacks. As a stand-alone scene, it’s right up there with the famous stalking scene in Cat People (1941). Cinematographer Joseph LaShelle also makes great use of shadows and highlights in the scenes with Dr. Landon, often highlighting Whit Bissell’s mad eyes and using almost expressionist techniques to heighten the menace in the scenes.

Bissell was a respected character actor who turned up in many A films, but often playing fourth or seventh banana in what were ususally rather proper and bland roles, so I imagine that he at least had a little fun going all-out mad scientists in I Was a Teenage Werewolf and its follow-up I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957, review). As mentioned, Malcolm Atterbury gives another standout performance in the film. The rest of the supporting cast is all competent without getting any chance to show off. But make no mistake, this is Michael Landon’s film. Landon has studied James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause and does a superb Dean impersonation — but it’s not just mimicry: Landon brings his own life and soul to the role of the conflicted, moody Tony. Much of it is non-verbal, Landon manages to tell a whole story just by a look. He’s got a twitchy, high-strung energy which he tries to barely contain within his thin frame, and which is set to explode whenever he is pushed over the edge. As the werewolf, he is truly explosive — agile, fast, menacing. As opposed to a lot of early werewolf movies, this film really gives the impression that the monster has the strength and speed of a wolf.

To Weaver, Cohen says that Landon did all his own stunts, and often went further than the director asked. According to Cohen, they were afraid that they might have killed their actor in the scene in which the werewolf attacks the gymnast, and Landon threw himself headlong into a jungle of metal chains. The scene in question is the best in the film. It sizzles with sexual energy, bewilderment and terror. Theresa is practising the parallel bars in her skimpy, skin-tight outfit, hanging upside-down when the werewolf enters. We first see the werewolf from her point of view, also upside down, a bold, effective choice by Fowler and LaShelle, which beatifully portrays the feeling of a world gone topsy-turvy into the realm of nightmare. Hanging there in a sexually provocative position, Theresa is a visual representation of a teenage sex fantasy come to life — one which teenage boys were not supposed acknowledge. Now, as a werewolf, Tony is given the means to release all that pent-up hormonal pressure in a raging rampage.

The werewolf makeup is quite good, even if the long, gnarly teeth are perhaps a tad over the top. In my opinion, it is perhaps the most stylish of all the werewolf makeups up to this point in time (including Jack Pierce’s iconic makeup for The Wolf Man), and looks a bit like a mix between that in The Wolf Man and in The Werewolf. It’s a leaner, meaner, more youthful werewolf. Cohen says most of it was actually makeup, courtesy of Phillip Sheer, who had picked up the tools of the trade during his time as makeup assistant at Universal. However, says Cohen, for some shots a rubber mask was used, as Michael Landon hated the makeup process. (Plus, any low-budget filmmaker worth his salt will use a mask for cost-cutting reasons in wide shots were a full makeup isn’t required.) The letterman jacket that Landon wears completes the iconic look, which has since been both imitated and spoofed several times.

To sum things up, I Was a Teenage Werewolf is a cheesy teen movie, but one which doesn’t squander its horror theme. It is highly entertaining despite a few dips in energy levels. It’s a clever exploitation film underpinned by some serious and timely themes, which, unfortunately, it doesn’t really explore in any greater depth. Gene Fowler’s direction is impressive, considering this was his first direction, and creates a couple of very memorable moments. The cherry on top is Michael Landon’s top-notch performance.

Reception & Legacy

I Was a Teenage Werewolf was released in June, 1957 on a double bill with Fred Sears’ SF spoof Invasion of the Saucer Men (review). As was often the case with AIP films, newspapers didn’t bother to review it. The trade press generally gave it a lukewarm reception. Variety called it “another in the cycle of regression themes is a combo teenager and science-fiction yarn”, but noted “good performances help overcome deficiencies”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor called it an “okay horror entry”, but also praised the cast, Michael Landon in particular. Harrison’s Reports was moderately positive, writing: “The story is, of course, fantastic, but it has been handled so expertly that it holds the spectator in tense suspense”. British Monthly Film Bulletin gave a harshly negative review, calling it a “second-rate horror” with bad transformation scenes and makeup that didn’t look like “the usual idea of a werewolf”.

However, despite poor reviews, AIP and Herman Cohen had the last laugh, as the film proved immensely popular, raking in over $2,000,000 at the US box office, and must have amounted to AIP’s most profitable film to date. The film’s most lasting legacy is perhaps its title. While the “I Was…” prefix had been used before, it was the “I Was a Teenage …” that caught on like wildfire, and was followed by films like I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, I Was a Teenage Vampire, I Was a Teenage Rumpot, I Was a Teenage Thumb, etc.

Today I Was a Teenage Werewolf has undergone a slight re-evaluation, although few would argue that it is some sort of underrated masterpiece. The film has a 5.1/10 audience rating on IMDb, and a 2.8/5 rating on Letterboxd. It has a 4.9/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes. ‘

Allmovie gives the picture a 2.5/5 rating, with Patrick Legare writing: “Although it suffers from its low-budget trappings and cheesy, dated script stylings, I Was a Teenage Werewolf is actually a rather clever analogy to what teens go through during adolescence: the physical and mental transformation from child to adult.” TV Guide says the movie “successfully combines the troubled teenager film and the horror movie”. Kim Newman at Empire gives it 3/5 stars, writing: “Besides the title, this has gone down in pop culture history because it’s a clever little film, rising above the limitations of its intermittently ridiculous script thanks to effective direction from Gene Fowler Jr and unusually committed performances.” And British Time-Out calls it an “all-time zero-budget schlock classic”.

Modern online critics are, on the whole, positive, non more so than Christopher Stewardson at Our Culture Mag, who gives a glowing 4/5 star review: “Despite its pacing issues and some ridiculous plot elements, I Was a Teenage Werewolf is a remarkable horror film. With a limited budget, Gene Fowler jr delivers a meaningful exploration of growing up, and the dangers posed by exploitative authority figures.” Richard Scheib at Moria rates the movie at 3/5 stars, writing: “The title concept makes for an amazingly powerful metaphor and that alone carries the film. […] I Was a Teenage Werewolf seems to be carrying the anger and alienation of the whole James Dean and hot rod generation on its shoulders. […] The film rips into the expectations of parents and middle-class values with a surly vengeance.” Finally Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV says: “Utter nonsense of course but it’s all part of the fun – and make no mistake, I Was a Teenage Werewolf is indeed a great deal of fun with only a few missteps”.

Cast & Crew

Producer Herman Cohen worked his way up the career ladder in the movie business from a young age — he began as a gofer in a movie theatre as a child and by the age of 15 he was well on his way to becoming a theatre manager. At the age of 25, in 1951, he produced his first film, The Bushwackers, and during the first half of the 50’s produced and sometimes co-wrote (often with Aben Kandel) around a dozen low-budget movies, including the abysmal Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (1952, review), and the slightly better post-apocalyptic thriller Target Earth (1954, review). In 1954 he was approached by James Nicholson who offered him to become a partner in the new movie company ARC, which later became AIP, but Cohen was tied up with obligations to United Artists. Nicholson instead founded the company with lawyer Sam Arkoff. Nevertheless, it was AIP that gave Cohen his greatest success, starting with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), and following up with I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), Blood of Dracula (1957) and How to Make a Monster (1958, review). He then relocated to the UK, where he produced such films as Konga (1961), Berserk (1967) and Trog (1970). He gradually moved more into distributing than producing, and in 1981 formed the distribution company Cobra Media. He passed away in 2002.

Gene Fowler was primarily an editor of some note. He started his career in the 30’s, and worked with directors like Fritz Lang and Samuel Fuller. He did some TV directing before getting his first chance at helming a movie with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), and directed a little more than half a dozen more movies in the 50’s, the best known being Paramount’s I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958, review) — a movie which is better than its title. In the early 60’s he directed some TV before returning to editing. As an editor he was Oscar nominated for his work on It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963), and won two consecutive Emmys for his TV work in 1973 and 1974. He allegedly also did some uncredited directing on the ill-fated SF movie The Astral Factor (1978), also released in reworked form in 1984 as The Invisible Strangler.

Romanian immigrant Aben Kandel started his career as a novelist in 1927, and also began writing plays. His 1931 hit play Hot Money was turned into films in 1932 and 1936, and one of his short stories was filmed in 1934, and one of his novels in 1940. He wrote his first screenplay in 1935. He wrote over a dozen screenplays in the 30’s, 40’s and early fifties, when he began writing for TV and struck up his long partnership with Herman Cohen. He co-wrote most of Cohen’s movies, which is what he is best remebered for today.

Anyone who has ever owned an old analogue TV will know who Michael Landon is. Less known is perhaps that he was born Eugene Maurice Orowitz in 1936, and under that name was a bit of a rising star as an athlete at USC. An arm injury put a stop to his athletic career and his university studies, and he did a couple of odd jobs and small roles before he decided to make a career out of acting and changed his name to Michael Landon in 1955. While he had over a dozen TV spots under his belt in 1957, Herman Cohen can take the claim of “discovering Landon” when he offered him the lead in I Was a Teenage Werewolf in 1957. Another lead role in Legend of Tom Dooley got him a spot at NBC’s new TV show Bonanza, in which he was cast as Little Joe Cartwright, the youngest of the three Cartwright brothers at the heart of the show — and he arguably became the most popular character in the internationally successful series, which ran for 14 years. Next, NBC cast him in the lead of another western series, and another international smash hit, The Little House on the Prairie (1973-1981), based on Laura Ingalls’ novel. This series ran for eight years. And for the next five years, he headlined Highway to Heaven, playing an angel on Earth, until his co-star’s health problems forced the show to a halt. Landon himself passed away from pancreated cancer not long after, in 1991.

Despite being teased endlessly by friends and co-stars because of his early horror movie “stardom”, Landon never disavowed the role that gave him his first brush with fame. In a special segment for Highway to Heaven, he again donned the werewolf makeup, and in an interview said that he had a lot of fun making the film, and was very thankful for the filmmakers giving him a stab at the role. It remained his only science fiction or horror movie.

Platinum blonde Yvonne Lime’s movie career was made up almost entirely of teensploitation films, from small roles in Warner’s Untamed Youth (1957) with Mamie Van Doren and Paramount’s Elvis film Loving You (1957), to her string of leads in AIP’s I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), Dragstrip Riot (1958), High School Hellcats (1958) and Speed Crazy (1959). She had a more varied career in TV and appeared regularly on the The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (1956-1958), Father Knows Best (1956-1960) and Happy (1960-1961). She dropped out of acting after marrying in 1968. After filming Loving You, Lime also went out on a “publicity date” with Elvis, and later published a kiss-and-tell called “My Weekend With Elvis” in Modern Screen magazine. One can only speculate as to whether the weekend she spent at Graceland posing with “the King” for a photographer was an actual date, or rather part of a publicity stunt meant to improve Elvis’ reputation with conservative critics who saw him as a menace to society. In the article, Elvis is described as a big teddy bear who goes to church, confesses his sins to the minister and served meat loaf and mashed potatoes to his dates. Whether Lime actually wrote the article, or if it was written bt a PR agent, is also questionable.

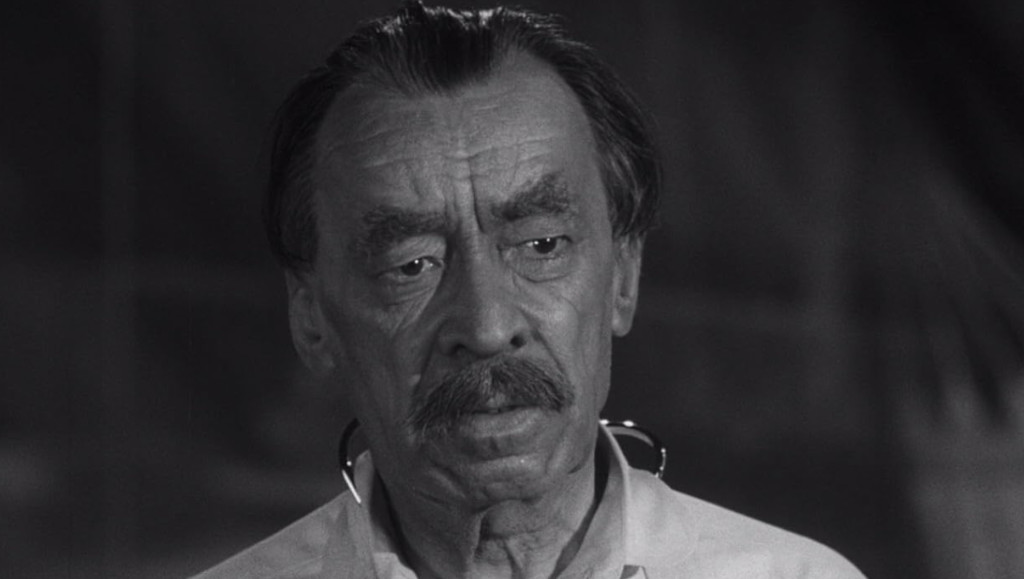

Whit Bissell is known to friends fifties horror and SF films as the eternal straight-laced, often mild-mannered and competent scientist, physician, government official or military man. He is best known to a wider audience for one of his rare villainous roles, that of the evil scientists who turns Michael Landon into a werewolf in I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). But his SF credit sheet is a mile long, and memorable performances include Dr. Thompson in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), a small but important role as one of the time traveller’s sceptical friends in George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960) and his portrayal of the evil Governor Santini in Soylent Green (1973). He also appeared in a small role in Lost Continent (1951, review), played a military scientist in Target Earth (1954, review), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), reprised his villain in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), appeared in Jack Arnold’s Monster on the Campus (1958, review), played Dr. Holmes in Irvin Allen’s TV movie City Beneath the Sea and reprised his role in a TV remake of The Time Machine (1978). Bissell was also a familiar face in science fiction TV from the fifties onward, appearing in many anthology shows, such as Out There and Science Fiction Theatre. His most prominent SF role was that of Lt. Gen. Heywood Kirk, one of the main characters of the TV series The Time Tunnel (1966-1967). Other memorable SF moments on TV for Bissell are the 1959 Christmas episode of Men into Space, the injured navy captain at the heart of the One Step Beyond episode Brainwave (1959), as small role as commanding officer in The Outer Limits episode Nightmare (1963), guest starring a young Martin Sheen, Mr. Lurry, the station Manager of the space station involved in the legendary Star Trek episode The Trouble with Tribbles (1967), and as one of the scientists studying the captured Hulk in The Incredible Hulk episode Prometheus: Part II (1980).

The small but memorable role as Theresa the gymnast was played by Dawn Richard. Richard’s acting career was two years short, and during that years she appeared in mostly bit-parts in eight movies and in 10 TV shows. Her most prestigious film was The Ten Commandments (1956), but she is best known for her role in I Was a Teenage Werewolf. She was more successful in her other career as a nudie photo model, she was Miss May 1957 in Playboy, and appeared in little clothing in numerous other men’s magazines.

The rest of the cast is made up of either reliable supporting and bit-part players or youngsters with rather few film credits. Barney Philips, playing the sympathetic police detective, had a long and prolific career in TV and film, and is perhaps best known as the Martian bartender in the Twilight Zone episode “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up”. Ken Miller, the singer of the awful song in I Was a Teenage Werewolf, actually did have a minor career as a recording artists, with singles like “Take My Tip” and “Teenage Bill of Rights”. While serving in Germany in 1954, he appeared in the German low-budget series Flash Gordon. He also appeared in I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and Attack of the Puppet People (1958, review), and was first-billed in the low-budget SF comedy It Came from Trafalgar (2009).

The role of the janitor Pepe is played by Russian-born and Moscow-trained actor Vladimir Sokoloff, who spent much the 20’s and 30’s in Germany and Austria, where he became famous character actor, and, among much else, appeared in G.W. Pabst’s classics The 3 Penny Opera (1931) and The Queen of Atlantis (1932). With the rise of the Nazis to power, he first fled to France, where he continued to appear in movies, such as Jean Renoir’s The Lowerd Depths (1936), and then to Hollywood, where one of his first appearances was in Wiliam Dieterle’s The Life of Emile Zola, in which he played artist Paul Cezanne.

In the US, Sokoloff was quickly typecast in “ethnic” roles. It didn’t matter whether they were Russian, German, French, Italian, Spanish or Greek, Chinese, Indian, Arab, Latino or Native American, Sokoloff played them all. He specialised in benevolent, kind-hearted and often wise characters, but also played the occasional sinister role. He is particularly well known for his appearances as Anselmo in For Whom he Bell Tolls (1943) and the Old Man in The Magnificent Seven. His science fiction films include Monster from Green Hell (1957, review), I was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and Beyond the Time Barrier (1960), in which he plays the leader of a sterile world in 2024. He acted until his death in 1962.

Makeup artist Philip Sheer created the makeup for I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), Attack of the Puppet People (1958), How to Make a Monster (1958), Invisible Invaders (1959) and The Cape Canaveral Monsters (1960). Composer Paul Dunlap also had a good run with low-budget SF films. He scored over a dozen SF movies, inlcuding Lost Continent (1951, review), Target Earth (1954), many of the AIP teensploitation horrors, and films like Frankenstein 1970 (1958, review), Destination Innerspace (1966), Cyborg 2087 (1966) and Panic in the City (1968).

Janne Wass

I Was a Teenage Werewolf. 1957, USA. Directed by Gene Fowler. Written by Herman Cohen, Aben Kandel, Gene Fowler. Starring: Michael Landon, Whit Bissell, Yvonne Lime, Barney Philips, Dawn Richard, Malcolm Atterbury, Ken Miller, Vladimir Sokoloff, Charles Wilcox, Louise Lewis, Cynthia Chenault, Michael Rougas, Robert Griffin, S. John Launer. Music: Paul Dunlap. Cinematography: Joseph LaShelle. Editing: George Gittens. Production design: A. Leslie Thomas. Set decoration: Morris Hoffman. Makeup: Philip Sheer. Sound: James Thomson. Produced by Herman Cohen for Sunset Productions & American International Pictures.

Leave a reply to Janne Wass Cancel reply