Scientists battle a novel element which theatens to blow the Earth to pieces in this 1957 Columbia cheapo. Dryly acted and clunkily written, but with an original enough idea to keep it going. 4/10

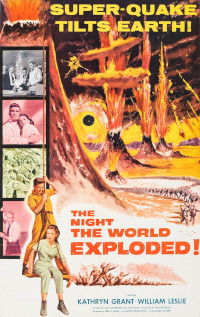

The Night the World Exploded. Directed by Fred Sears. Written by Jack Natteford & Luci Ward. Starring: Kathryn Grant, William Leslie, Tristram Coffin. Produced by Sam Katzman. IMDb: 5.3/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Geologist David Conway (William Leslie) invents a machine that will predict earthquakes. The moment he turns it on, it predicts a massive, devastating quake in California. Along with his boss, Ellis Morton (Tristram Coffin) and assistant Laura “Hutch” Hutchinson (Kathryn Grant), they try to alert the authorities, to no avail. The disaster strikes, with thousands of deaths as a result. More quakes follow all over the world, and Conway and his team descend to the bottom of Carlsbad Caverns to investigare what is going on with the Earth. Here, they find a new element, which they dub “Element Number 112”, a new element that expands and heats rapidly when it comes in contact with air, resulting in a tremendous explosion. This element is now pushing for the surface, and Conway calculates that it may soon destroy the entire planet.

Columbia’s The Night the World Exploded is a 1957 low-budget movie released as the lower bill with the literal turkey The Giant Claw (1957, review). It was directed by Fred Sears and was cast with a rather anonymous cast – perhaps with the exception of Kathryn Grant.

Hutch says at one point that it feels like the Earth is coming back for revenge for all the resorces we have robbed her off. It turns out that she isn’t wrong: the ore seems to penetrate in just those areas where oil drilling and mining has been going on, as the Earth’s crust has been thinned out, allowing the ore to push upwards.

In an amazing geopolitical feat, Conway is able to bring together all the world’s greatest scientists, and when feeding the combined knowledge about the new element through the supercomputer Datatron, they come to the result that the Earth has 28 days to destruction. Conway calls upon all the nations to put aside their differences and flood the areas where the ore is rising, as it will be rendered harmless once it is submerged in water. The world’s nations start breaking dams and manipulating the cluouds for rain, and for once it seems that all the people of the planet are working together for a common goal. But time is running out.

Oh yes, and Hutch is really in love with Conway, but he is too preoccupied with work to see it, so she’s going to marry Brad, because, you know, a girl just has to marry at some point.

Background & Analysis

There is not very much information on the production of this film online, and relatively few of my usual sources cover it, which is unusual for a 50’s mainstream Hollywood science fiction movie. Those who do cover it generally don’t have much positive to say about it.

Most of the film’s meager budget seems to have gone into the sets. There’s a relatively impressive reconstruction of the Carlsbad Caverns, which would be more realistic was it not so brightly lit. There’s also a few helicopter scenes and a finale filmed at a Los Angeles electric power plant which make the film a little less claustrophobic. Add to this a large proportion of stock footage. However, like its sister movie, The Giant Claw, much of the original footage is studio-bound, and there are a few too many nonsdescript rooms in which much of the dialogue takes place. However, as Sears has proven in previous films, he is able to deftly switch locations and use blocking to avoid making his films feel cramped, despite often being filmed on small, nondescript sets.

As said, The Night the World Exploded uses a lot of stock footage. It is sometimes painfully obvious and not particularly well worked into the story. For example, much of the earthquake footage is obviously stock footage of controlled building demolitions. There’s a good portion of very impressive miniature and model shots of the demolition of a dam in the climax of the film. However, all this footage is ripped straight from the 1938 Republic movie Born to be Wild, and the brilliant effects are created by the legendary Lydecker brothers.

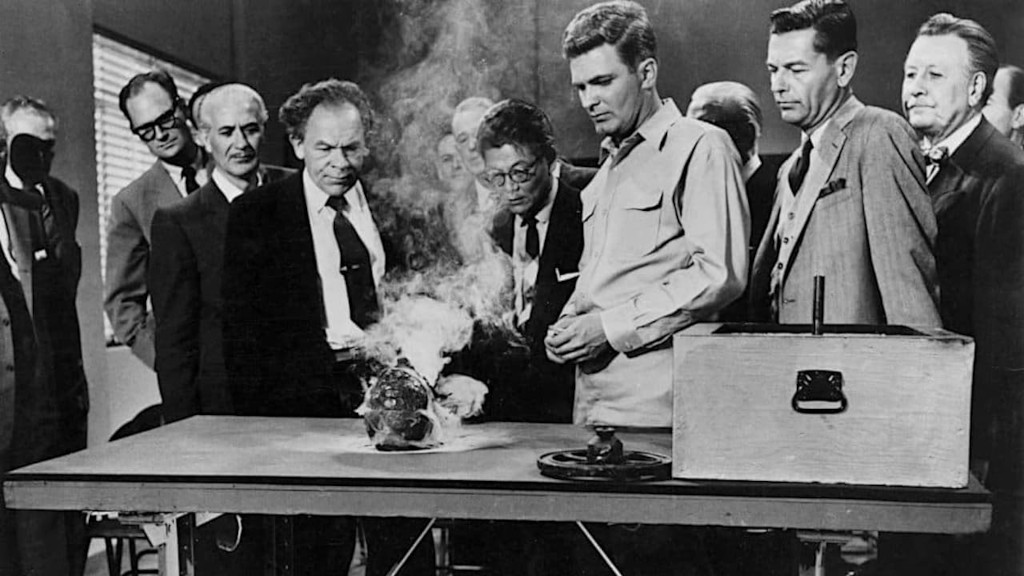

The script is so-so. Written by husband-and-wife team Jack Natteford and Luci Ward, it gets props for an original idea. Interestingly, Universal released a movie with a very similar premise just two months later, The Monolith Monsters (review), and the films must have been in production around the same time. The Night the World Exploded wastes no time on jogging itself into the plot – we’re not three minutes into the film when Conway predicts the first earthquake. However, the middle part of the film is rather low on plot and spends too much time explaining Element 112. By the time Conway gets around demonstrating it to the other scientists, we the audience have already been through the exercise twice already. It’s also quite dumb. Conway takes the scientists out to a bomb range in order to show off its explosive capabilities and sticks a bit of ore to a plastic globe, which he hangs in a tree. Of course, the globe explodes. But a firecracker would have blown up that globe. Conway doesn’t even tell the scientists what amount of ore he uses, rendering the whole demonstration completely useless.

The romantic subplot is, as usual, tacked on and redundant. There’s also a lot of talk about Brad, whom Hutch is going to marry, but we never see the guy. When Conway and Hutch finally get together, it turns out all she needed to do was say the word. The film is one of the many 50’s B-movies that tries to be feminist in a sort of backwards way. Hutch is described as a brilliant scientist and an invaluable member of the team, and she never backs away from danger. When a cave collapses around her, she doesn’t panic, but keeps reading out important measurements from the “pressure photometer”. But then there’s also a scene in which Hutch freezes when climbing down a rope ladder, and Conway has to talk to her like a child in order to get her down the cave shaft.

In an interview in Nik Havert’s book The Golden Age of Disaster Cinema, Kathryn Grant says she enjoyed working on the film, and thought her character gave feminism a boost. She also says that director Fred Sears was “very pleasant”; “Good directors keep things going, keep things pleasant, and get it done on time, and he did that”. However, the fast pace and long shooting hours seem to have taken a toll on the actress, as she recalls that while shooting at the electrical power plant, she managed to fall asleep on a chair, despite the “maddeningly loud” noise around her.

The science is, of course, “complete hokum”, as reviewers of the day would have stated it, but once the premise of the film is stated, the script manages to follow up on its own logic. However, at one point the narrator (as in The Giant Claw, director Sears did the narration, in order to cut costs) tells us that the Earth has shifted three degrees on its axle. However, this is never mentioned again, and seems not to be part of the problem.

In my previous review of The Giant Claw, I mentioned that by the late 50’s, fewer and fewer Hollywood science fiction movies seemed to make political statements, a stark contrast to the early 50’s, when all SF films seemed in one way or the other to comment on geopolitical issues. The Night the World Exploded, however, is an exception. It’s clear that screenwriters Natteford and Ward have seen The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), as it borrows heavily from that film. There’s a scene in which Conway tries to convince the Assistant Secretary of Defense (John Zaremba) to call together all the world’s leading scientists for a meeting, and is given a reply almost identical to that in the earlier film. In another scene, Conway calls upon all nations to put aside their differences and work toward a single goal to ensure the future of the planet, echoing the Klaatu’s final monologue about international cooperation and disarmament.

However, the film’s political impact is somewhat muddled here, as the problem the world is facing is not one related to the cold war in the slightest, but a natural — ecological — disaster. In fact, The Night the World Exploded is rather interesting as one of the very first eco disaster films not related to a nuclear war. In fact, it is the oldest film bearing the IMDb tag “Ecological disaster”. Of course, it’s not the first film to mention humanity’s poor treatment of mother nature — one can argue that this is one of the main themes in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), for example. However, it is unusual in the way that it makes the big menace of the movie a direct result of the exploitation of nature, a sort of eco disaster theme that wouldn’t really show up in cinemas en masse until a couple of decades later. However, the film is more invested in the plot than in any serious exploration of the theme.

The acting is mostly competent but dull. William Leslie makes for an unengaging leading man, seemingly delivering all his lines in the same monotone tone of voice, and failing to project any kind of charisma. He has a very impressive chin, though. Kathryn Grant is cute, but she isn’t capable of selling us on the idea that she is a university-educated geologist. Granted, with this script, few actresses would have been capable of this. Tristram Coffin is, as per usual, reliable, but his role doesn’t give him many opportunities to shine. A standout performance is given by Paul Savage, playing a sympathetic ranger who falls prey to the explosive capabilities of Element 112.

In his best moments, director Fred Sears was capable of both finesse and atmosphere, two elements sorely missed from The Night the World Exploded. He isn’t helped much by cinematographer Benjamin Kline, a Hollywood workhorse veteran, who over-lights the cave scenes and fails at using lighting for anything but flatly illuminating the sets and action. What location shooting there is, is not taken advantage of. The script tries to build some drama and tension at the end of the movie, but it is ruined by the boring and unengaging cinematography and direction.

Despite all of its flaws, though, I still thoroughly enjoyed The Night the World Exploded. It’s got an original enough idea to stand out, even of the low budget prevents it from taking full advantage of it. At 60 minutes it doesn’t outstay its welcome, despite occasionally treading water. There’s enough drama to keep you at least halfway interested.

Reception & Legacy

The Night the World Exploded was released on a double bill with The Giant Claw in June, 1957 and received little interest from the newspapers. Philip Ungerer at the New York Democrat and Chronicle wrote about the double bill: “As is usually the case with these film types, yesterday’s opening day audience came forth with more laughter than squeals”, although I suspect the companion picture with its wonky bird monster drew down the biggest laughs. Ungerer also notes that the “joint agitation” of William Leslie and Kathryn Grant in The Night the World Exploded is “at times […] downright frightening”, although it’s unclear if he means this in a positive or negative way. G.B. of The Miami Herald says that Grant “does more with her role than William Leslie does in his wooden portrayal of a male counterpart”.

Neither did the trade press lavish much attention on the movie. Gilb. at Variety called it “a modest science fiction entry” and said that “none of the performances are particularly convincing”. Vincent Canby at the Motion Picture Daily named it “a yarn of extremely dubious science and of elementary fiction”. Harrison’s Reports said: “Since the story is too fantastic to be taken seriously, the thrills offered are mild at best”.

Today, the film has a 5.3/10 audience rating on IMDb based on 700 votes, and a 2.9/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on a little more than 250 votes. Hal Erickson at The New York Times/Rovi/Allmovie says: “Despite all the scientific doublespeak, The Night the World Exploded is doggedly nonintellecutal in its execution and appeal.” TV Guide calls it a “dull science-fiction outing”. Phil Hardy’s Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies calls it “a pedestrian offering”. In Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren praises the original idea, but nevertheless says the movie is a “drab, dull exercise relying far too much on stock footage”. According to Warren, the film is also “damaged by more obvious sexism than average, even for the 1950s”.

The Night the World Exploded gets little love from online critics. Crippa at Disaster Movie World gives it 1/5 stars, writing: “Ideas-wise, I’ve certainly heard worse, but The Night the Earth Exploded is told in such an unimaginative and bare-bones fashion that it had me bored despite clocking in at a mere 64 minutes”. Derek Winnert gives it 1/4 stars, blaming the screenwriters for the” almost total failure here, because the script’s lack of intelligence and the production’s lack of budget combine to sink it”. Dave Sindelar says: “The idea is fairly good, the story is told efficiently, the script is decent enough, and the actors would be acceptable with a little sympathetic direction. But to really do justice to the idea, you need to throw a decent amount of money at it, and that just doesn’t happen here with Sam Katzman holding onto the pursestrings. Consequently, the movie never moves into the realm of believability, and you spend your time thinking about how much better it would have been given a proper treatment.” However, Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster is at least slightly sympathetic: “It’s not much. But then, its main job was to fill time, so that isn’t exactly a surprise. It is, however, short and moves quickly.” And Kris Davies at Quota Quickie says: “This is a bit of a pedestrian film that takes a while to get going but ultimately is worth persevering with. An fairly intelligent science-fiction plot and good use of stock footage overcomes the shortcomings with the budget. A reasonable little film.”

Cast & Crew

Director Fred Sears was born in 1913 and started his career as a stage actor, producer and director, until he was hired by Sam Katzman as a dialogue coach for Columbia in 1946, a company he stayed loyal to until his death in 1958. He also appeared numerous times in front of the camera in small roles, before graduating to direction in 1949, often getting handed westerns, crime films and other B-movies. His films were routinely undistinguished up until 1956, when Katzman handed him the double bill of Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (review) and The Werewolf (review). A more staple diet of his was the teenage movie, such as Teen-Age Crime Wave (1955), which made him a natural choice for director when Katzman was able to get a contract with rock musician Bill Haley, whose megahit “Rock Around the Clock” had taken off after being featured in the intro of MGM’s film Blackboard Jungle in 1955. Rock Around the Clock (1956), produced by Columbia, directed by Sears and featuring not only Bill Haley and His Comets, but also The Platters, Alan Freed, Tony Martinez and Freddie Bell, is often considered the first rock n’ roll musical film, and became a major sensation, taking home over $4 million dollars at the box office. However, Sears wasn’t able to capitalise on the film’s success, stuck as he was at Columbia, designated to its low-budget outfit, where he kept grinding out gangster movies, teen movies, westerns and the occasional SF film. Katzman hoped to repeat the success of Earth vs the Flying Saucers by having Sears direct another SF double bill in 1957: The Giant Claw and The Night the World Exploded.

The biggest star name of the cast was Kathryn Grant, stage name for Olive Kathryn Grandstaff, born 1933 in Texas. Appearing on stage since childhood, she studied acting before moving to California in 1933, where a beauty pageant was her ticket to the movies. From 1953 to 1955 the dark-haired beauty appeared only in uncredited bit-parts before getting credited roles, primarily at Columbia, in 1956. She had small parts in bigger movies and co-starring roles in B-movies of various genres.

By 1957 Grant was in the headlines not so much because of her acting career, but because of her relationship with actor and crooner Bing Crosby, whom she married later the same year, changing her name to Kathryn Crosby. However, her acting credentials also took a step upwards in the spring and summer of 1957, as she appeared opposite Audie Murphy in The Guns of Fort Petticoat and opposite Tony Curtis in Mister Cory. Her career continued to improve when she appeared in the female lead of the Ray Harryhausen classic The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) as Princess Parisa, in a large supporting role in Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959) and in a co-lead in Irwin Allen’s The Big Circus (1959). However, she quit her movie career soon after marrying the over 30 years older Bing Crosby, as he disapproved of her working – she did manage to squeeze in a few TV appearances in the 60’s. In the 60’s she also got an education as a nurse, although I haven’t found any information as to the extent she did or did not practice as one. After Bing’s death in 1977, Kathryn returned to stage acting, did the occasional TV and movie appearance and hosted a talk show on a local TV network. On her inactivity during her marriage to Crosby, she wrote in one of her biographies: “He was a pretty cute kid, when it came to convincing a girl that what she really wanted was to stay home and to scrub floors. He didn’t know that he was a male chauvinist pig, but he was!” As of November, 2023, Kathryn Crosby is still around at the age of 90.

Another Texan, William Leslie, appeared regularly at the Pasadena Playhouse in the late 40’s and early 50’s, before making his screen debut in 1952. After a while struggling, he was put under contract with Columbia in 1954, but was never able to make a name for himself. He got stuck playing second or third fiddle in mostly B-movies – The Night the World Exploded was his only lead at the studio. He struck out as a freelancer in 1958, but his career trajectory hardly improved. His second lead came about in 1965, in another science fiction movie, Mutiny in Outer Space, produced by low-budget schlock specialist Hugo Grimaldi. This remained his last film. After a couple of TV appearances, he apparently decided to call it quits oin 1967, and there seems to be little information on what he did after that, but he lived to a respectable age of 80 and passed away in 2005.

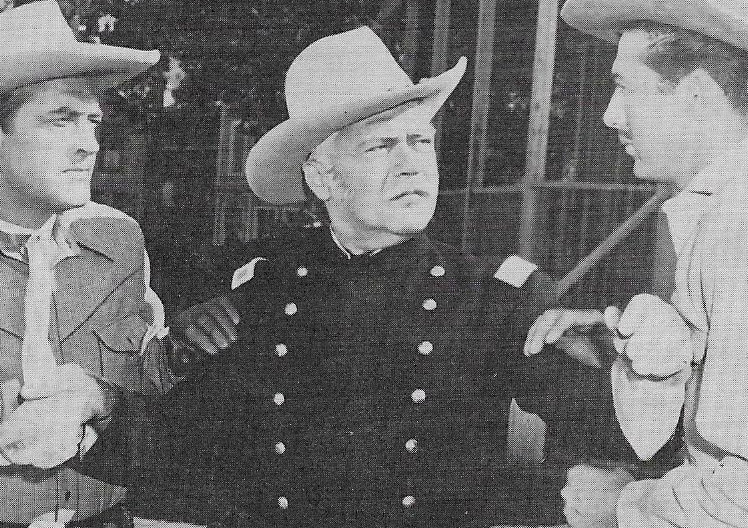

Tristram Coffin was a B-movie workhorse, with credits in over 200 films or TV series. He is probably best known for playing the titular hero in the film serial King of the Rocket Men (1949). His leading man roles were few and far between, more often he played heavies in cheap westerns, bit parts in crime movies or military supporting types. An exception to the rule was in one of Bela Lugosi’s so-called “Monogram Nine”, referring to the number of films the horror star made for the studio in the early 40’s. This was the bizarre horror/gangster film The Corpse Vanishes (1942, review), also produced by Sam Katzman (Monogram was the precursor to Columbia).

While third-billed in The Night the World Exploded, it would be an exaggeration to say Coffin’s role was a co-lead. He was pushed down to small supporting roles in his other sci-fi outings, Flight to Mars (1951, review), Creature with the Atom Brain (1955, review), The Crawling Hand (1963) and the Leslie Nielsen vehicle The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler (1971). He also appeared in the first all-out science fiction TV show, Captain Video, Master of the Stratosphere (1951) and had a number of different roles in the original Superman TV show (1952-1958). He became famous as the “corpse that got up and walked off screen” in 1954 during the first episode of the live-aired TV show Climax! According to Coffin himself, the gaffe was blown out of proportion, especially by Johnny Carson, who repeatedly recounted the story of how a actor named Coffin played a corpse that “got up from its stretcher and leisurely strolled off screen”. In fact, what happened, said Coffin, was that he was lying on the floor and was supposed to crawl away — under the camera — to make room for a boom shot on lead actor Dick Powell. But because his cue came too early, he was still visible in camera as he shimmied away with his blanket.

The role of the sympathetic Ranger Kirk who gets blown to smithereens is played by Paul Savage, who struggled on as a bit-part movie actor and TV guest actor between 1952 and 1958, before he chanced upon an ad calling for submissions for a story treatment for an episode of the short-lived western series Casey Jones in 1957. His treatment was accepted, and the episode was well-received, and Savage soon found himself in demand as a writer, deciding that this was where his talents really lay. While he contributed to other genres as well, he specialised in westerns, and his first more stable gig was as writer for Laramie, for which he wrote 14 episodes between 1959 and 1963. However, he is best known as the executive story consultant on the long-running, critically acclaimed and hugely popular show Gunsmoke, a job he held for 12 years between 1965 and 1979. His attachment to Gunsmoke also made him a writer in great demand for other projects, and over the years he wrote for shows like The Streets of San Francisco,The Walton’s, Matlock, TJ Hooker and Murder She Wrote.

The rest of the cast is filled with Columbia bit-part regulars and Hollywood veterans. Gerald Mohr, whose trademark was a smooth, barytone voice and strong resemblance to Humphrey Bogart, started working in radio in his teens in the early 30’s and became part of Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre, opening the doors to Broadway. In the 40’s he was typecast in Bogartian trenchcoat roles, often as leads in B noirs. However, work in the 50’s was getting scarce as the popularity of the noir waned, and Mohr found himself mainly stuck in low-budget fare, ping-ponging between leads in risible films like Invasion U.S.A. (1952, review) and uncredited bit-parts in slightly more prestigous movies, and instead found more dignified work as a guest star on TV shows. His other notable science fiction outing was as the lead in Ib Melchior’s cheap but interesting The Angry Red Planet (1959).

Austrian theatrical actor, director and photographer Otto Waldis came to the US in 1940. A renowned stage presence in Vienna, he relocated to Birmingham, Alabama, where he worked as a professional photographer, before moving to Los Angeles and starting work in movies in 1947. We have encountered him before on Scifist in the role as the crazed communist villain in William Cameron Menzies‘ uneven communist invasion film The Whip Hand (1951, review). He loathed the role, but at the time, while working somewhat steadily, he was offered mainly small supporting or bit parts, and a man’s gotta eat. He had few moments to shine in his movie career, but had small parts in big movies like Max Ophüls’ Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948), Henry Koster‘s The Robe (1953) and Stanley Kramer’s Judgement at Nuremberg (1961). He had a substantial part in the main cast of the hollow Earth movie Unknown World (1951, review), as one of the scientists looking for an underground world for mankind to shelter from nuclear war in. He appeared uncredited in The Night the World Exploded (1957, review) and had a supporting role as Prof. von Loeb in Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958, review).

Dennis Moore was a prolific gunslinger in over 200 westerns serials, Poverty Row films and TV shows, and hit his career peak during WWII, when many of the stars of Hollywood were drafted into service. He played the lead in a number of serials, including the SF-ish The Purple Monster Strikes (1945). An instantly recognisable face, if not name, is John Zaremba. Zaremba appeared in a multitude of sci-fi films and series over the course of his career, such as The Magnetic Monster (1953, review), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), The Night the World Exploded (1957), Frankenstein’s Daughter (1958) and Moon Pilot (1962). He was one of the stars of the TV series The Time Tunnel (1966-1967) as Dr. Raymond Swain, and had a recurring role in Batman (1966-1969) as Mr. Freeze’s butler Kolevator.

Benjamin Kline was an extremely prolific cinematographer who started his career in 1920 and worked over five decades, often turning out close to two dozen films a year. In 1957 alone he also shot The Man Who Turned to Stone (review), The Giant Claw, Zombies of Mora Tau and The Night the World Exploded.

Janne Wass

The Night the World Exploded. Directed by Fred Sears. Written by Jack Natteford & Luci Ward. Starring: Kathryn Grant, William Leslie, Tristram Coffin, Raymond Greenleaf, Charles Evans, Frank J. Scannell, Marshal Reed, Fred Coby, Paul Savage, Terry Frost, Gerald Mohr, Otto Waldis, John Zaremba. Cinematography: Benjamin Kline. Editing: Paul Borofsky. Art direction: Paul Palmentola. Sound: J.S. Westmoreland. Produced by Sam Katzman for Clover Productions & Columbia.

Leave a comment