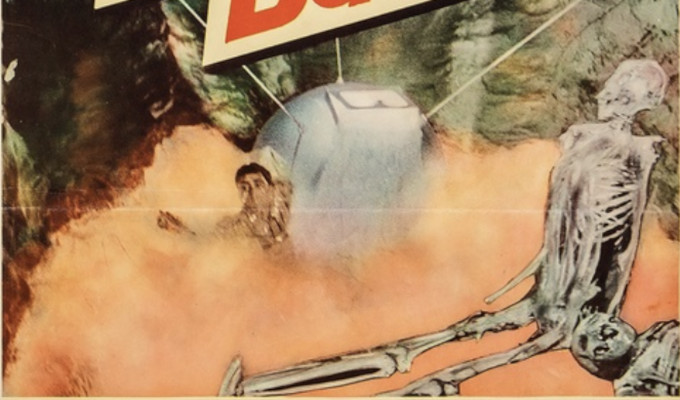

The search for yet another lost husband in the Mexican jungles leads to a crashed satellite inhabited by a murderous alien blob. Gramercy’s 1958 SF jungle adventure has a good idea but lacks both script and interest. 2/10

The Flame Barrier. 1958, USA. Directed by Paul Landres. Written by Pat Fielder, George Worthing Yates. Starring: Arthur Franz, Kathleen Crowley, Robert Brown. Produced by Arthur Gardner & Jules Levy. IMDb: 4.6/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Scientist and businessman Howard Dahlmann (Dan Gachman) has disappeared in the Mexican jungle while looking for a crashed satellite. Now wife Carol has come to the Yucatan peninsula in order to convince the hardened trekker brothers Dave and Matt Hollister (Arthur Franz, Robert Brown) to join her in an expedition to find her husband. Hard-headed Dave says no: too dangerous, the area will be impassable in the rain season. Heavy-drinking Matt says: look at that babe.

So begins The Flame Barrier from 1958, one of four SF/horror movies released by Arthur Gardner’s and Jules Levy’s Gramercy Pictures through United Artists in 1957–1958, of which three are generally well-regarded and one is not. The Flame Barrier being the one that is not. All four movies were written or co-written by Pat Fielder, and three were directed by Paul Landres, including this one. It was released in April, 1958 as the bottom-bill to Gramercy’s The Return of Dracula.

It probably comes as no surprise that Dave eventually feels that the Yucatan peninsula isn’t quite as impassable in the rain season as he originally thought, after being offered a substantial payment for the brothers’ efforts. Off the trio goes: obnoxious drillmaster Dave, playboy Matt and pampered, rich trophy wife Carol, picking up a trio of superstitious Indian porters on the way, led by Waumi (Rod Redwing). Along the way, Carol struggles with spiders, snakes, poisonous plants and her blouse getting all muddy, while Dave never misses a moment to belittle her and boss the rest of the party around. Matt passes the time by making several unsuccessful passes at Carol. The natives are, as per usual in these films, restless, as strange goings-on have been going on in the jungle near where Mr. Dahlmann thought the satellite had crashed.

First one native guide runs off, then the other, but they both turn up again with strange burns on their chests, after which their bodies self-ignite and burn down to the bones in seconds. After several arguments about whether to stay or go on, the remaining four explorers reach Dahlmann’s camp, where they find scientific equipment, as well as the chimpanzee which had been the passanger of the disappeared satellite – alive and well. Soon they also find both Dahlmann and the satellite in a cave. Unfortunately both have been engulfed in some sort of glowing protoplasm, and Dahlmann is quite certainly dead. The protoplasm also has a protective electric shield surrounding it, as demonstrated by one disintegrated chimpanzee. Dave concludes that Dahlmann’s theory that some alien force beyond the “flame barrier” 200 miles above Earth caused the satellite to crash, and now it has come to Mexico. (By this time Matt has stopped making passes at Carol, and Carol and Dave have become an item.)

Investigating Dahlmann’s notes, the three explorers (Waumi disappeared at some point during which my attention was probably wandering) find out that Carol’s husband had worked out that the ectoplasm and its deadly electrical sheild double in size every two hours. They realise that they can’t turn back, as they aren’t able to move fast enough to outrun the growth of the deadly blob. Some way or the other it, has to be stopped. Dave figures they could hook up Dahlmann’s solar battery to two metal ore veins running along the cawe wall against which the satellite is propped, thus electrocuting the alien entity. But they have only two hours to do it before the menace doubles in size, and it may involve the unselfish sacrifice of the disappointing brother Matt in order to redeem himself and give Dave and Carol a clear field to jumpstart their romantic entangement.

Background & Analysis

Between 1952 and 1954 the producer duo Jules Levy and Arthur Gardner produced three low-budget crime thrillers for United Artists. In 1957, they convinced the studio that they had the talent and know-how to make low-budget science fiction and horror movies that felt and looked like they were more expensive than they were. The result was the surprisingly good 1957 pairing of The Vampire (review) and The Monster that Challenged the World (review). In the fall of 1957 they were completing their third movie in the bunch, The Return of Dracula, when, in October, the Soviet Union launched the first man-made satellite, Sputnik, effectively igniting the cold war space race.

Studios all over Hollywood were now in their own race to capitalise on this world event. Likewise Levy and Gardner at Gramercy, who came up with The Flame Barrier, which went into production in December, 1957, and premiered in early April 1958. According to one trade paper piece during pre-production, Gramercy had bought the rights to a story by writer and producer Sam X. Abarbanel with the title “The Flame Barrier”. However, Abarbanel received no screen credit, and it is possible that the screenwriters threw out his story and settled for borrowing the title, if indeed such a story ever existed. Prolific SF screenwriter George Worthing Yates is instead credited for both the original story and the screenplay. Yates worked on some good projects previously, like Them! (1954, review) and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), but also a number of clunkers. Levy and Gardner probably weren’t quite happy with Yates’ work, and turned it over to Pat Fielder, who had written the previous three scripts, infusing them with both intelligence and emotional depth. Or perhaps Yates just gave up and passed it over.

Unfortunately, all involved later admitted to film historian Tom Weaver that their work on The Flame Barrier fell far from the mark. Arthur Gardner admitted that the screenplay wasn’t very good, and Pat Fielder says they made the mistake of trying to follow the formula of previous jungle adventure films. She adds that the film was made on a very thight budget and schedule, with less than a week of shooting.

The film had a budget of around $100,000, and was almost entirely studio-bound, with the exception of a few jeep scenes probably filmed in Griffith Park. There’s a small bar set and a hotel room in the beginning of the film, and after that almost the entire movie is shot on a jungle set with potted plants probably handed down from another film, or next to a tent canvas. The ending has a few unconvincing cave sets and the alien blob encompassing Dahlmann and the satellite. It seems to be made of backlit crumpled cellophane. The actors playing the Native Americans wear the same black wigs that seemed to be passed around anytime a low-budget film called for South American Indians. There’s a small python and an unconvincing puppet of a venomous snake, as well as an iguana and what may be stock footage of a couple of tarantulas. And a chimp, of course.

The script follows the basic pattern of a type of movie that was extremely popular in the latter part of the 50s, the jungle SF mystery movie. Its popularity probably stemmed in part from the fact that it gave the producers a chance to appeal to fans of several genres. But it was also a cheap and quick type of film to make, requiring a minimum of effort in regards to scriptwriting and production values, and one that could easily be cobbled together with a week of principal photography. You could rent a standing jungle set with potted plants at almost any studio, and by arranging the plants in different configurations, you could spend most of the film on a single set. In regards to screenwriting, the jungle quest provided an almost ready-made plot that could easily be copied from similar films with little variation. All you really needed was a beginning, which set up the scenario, and an end, in which the scenario is resolved. In The Flame Barrier, these take up around 25 minutes of plot in the 70-minute movie. Then, the jungle quest provides a sense of forward motion just due to the fact that the protagonists are moving from point A to point B with a purpose, and to get from the one point to the other must overcome a number of obstacles and difficulties, which can easily be filled in from the catalogue of jungle movies, and don’t really need to have any bearing on the actual plot: encounters with dangerous animals, crossing difficult terrain, a bout of jungle fever, loss of provisions, native guides running off, the jeep getting stuck, a cute monkey, a falling out within the party and the development of a romance. And, hey presto, you have a film.

The three science fiction concepts in The Flame Barrier are all borrowed from previous works. First of all, there’s the theme of something dangerous in the jungle, affecting the wildlife and the natives. There are numerous examples of this theme, but the latest very similar movie was Al Zimbalist’s Monster from Green Hell (1957, review), which hit the theatres in May, 1957. Here an experimental rocket carrying wasps crashes in the jungle, and the wasps grow giant due to cosmic radiation. The idea of a man-made object carrying with it a threat from space was first, and famously, explored in BBC’s TV series The Quatermass Experiment (1953, review), and reached the US through Hammer’s movie adaptation The Quatermass Xperiment (review) in 1955. Finally, there is the theme of some entity growing exponentially, threatening the world. This trope was essentially created by radio pioneer Arch Oboler with a segment of his radio show Lights Out!, called “The Chicken Heart”, which aired in 1937. The story involves an experimentally enhanced chicken heart, which is both indestructable and continues to grow exponentially, eventually throwing the Earth out of orbit. The idea was well adapted by Curt Siodmak and Ivan Tors in the movie The Magnetic Monster (1953, review) and by Kurt Neumann and Irving Block in Kronos (1957, review). As an avid science fiction fan, George Worthing Yates would have been familiar with Oboler’s work.

If we start with the good stuff, then The Flame Barrier is fairly well acted, at least as far as the three leads go. The Native Americans are played by bit-part actors who do their best “scared native” schtick, and can’t be blamed for the inane way in which the script portrays them. For what it is, it is competently directed. Paul Landres was seriously hampered by the circumstances, but he knew how to put together a movie. The special effects are at least OK, if cheap. Pat Fielder, who did such a good job scripting Gramercy’s previous SF movies is stuck with an unthankful job in polishing George Worthing Yates’ script. But the dialogue in The Flame Barrier is a notch above the usual in these kind of movies, and the characters are at least halfway interesting, if one-dimensional. Deep down in the film’s core, there is a good idea, if badly handled.

The major problem with The Flame Barrier is that the ratio between plot and padding is out of all proportion. After the initial setup and presentation of characters and concept, we spend 45 minutes trecking through the jungle where nothing of relevance to the actual premise happens. We’re around 55 minutes into the 70-minute movie when the protagonists finally reach the downed satellite and the alien blob, and the plot proper can actually begin.

Furthermore, if you stop to think even for a minute, nothing makes sense. First of all: why is the satellite in a cave? Did Dahlmann drag it there? Why? Dahlmann is found almost snuggled up against the satellite. This means he must have been caught in the alien’s grip almost immediately when it started growing. But we know that Dahlmann was aware of the dangers of the satellite, and even made notes about both its ray shield and its doubling in size. If he knew about these, why would he have gone near the satellite in the first place? And if he was caught unaware, how and when could he have made the notes? And why is Dahlmann caught in the blob, and not disintegrated by the electrical shield, like everything else that comes in contact with it? During the jungle trek, two of the natives are badly burned and later disintegrated in the same way as the ape when it touches the alien’s shield. But the natives have never been near the cave in which the alien resides. How did they get burned? Is there a second alien roaming the woods that the movie never lets us know about? And we are told it’s been two months since Dahlmann disappeared. How did the chimp now starve to death during two months tethered to a tent pole? And I suppose it is theoretically possible to find a vein of metal ore so pure that it can be used to conduct a high level of electricity for several metres, but I find it unlikely. Plus, can you electrocute a being that is able to generate a a deadly electrical field? All in all, the inconsistencies and logic holes are difficult to swallow even at a first viewing.

If we are nitpicking science, then let’s talk about the film’s title. According to the film’s narrator, the “flame barrier” is a barrier 200 miles above Earth’s surface above which no man-made object has ever passed, because everything catches fire when breaking the flame barrier. Of course, there is no such thing, and even in 1958 everyone knew there was no such thing. The “flame barrier”, if such a term might ever have been used, could have referred to the metaphorical “barrier”, determined by an object’s speed and angle in relation to Earth, when re-entering Earth’s atmosphere, when it catches fire. If we accept the idea that the film presents, however, then a better title might have been “Beyond the Flame Barrier”, as it is from beyond the barrier that the aliens comes. And the film was actually released under that title at some point.

The jungle set is what it is and the cave set is unconvincing. The cellophane alien looks like a cellophane alien, but it is somewhat effective, especcially with the petrified face of Dahlmann captured inside it. A better script could have lingered more on the horror of seeing your husband engulfed in a horrible alien entity, but The Flame Barrier just sort of skims over the matter. The little bit of livelyness that Pat Fielder is able to inject into the script, the decent performances and the overall competence of the producers and director are what keeps the movie from falling into the dark pit of awfulness where films like Jungle Hell (1956, review) resides. It’s not a film I would recommend to anyone, but if you are forced to sit through it, it is possible to do so without being bored to death.

Reception & Legacy

The Flame Barrier was released on April, 2, 1958, as the bottom bill to The Return of Dracula. It was the last science fiction film released by Gramercy. In an interview Tom Weaver asks why the studio stopped making SF movies, as they clearly had an aptitude for it. Arnold Laven and Arthur Gardner say that the films simply weren’t very profitable, despite the low budgets. Gardner explains: “I don’t thing United Artists really knew how to release this type of film at the time. We’d had been far better off if we had made them for a distributor like American International or one of the other smaller releasing companies.”

BoxOffice called The Flame Barrier “wild and wooly” with “sufficient excitement” to “satisfy the most action-minded fan”, but also referred to its “opening scenes” as “rather routine”. Saying that the film “builds up suspense steadily”, the magazine predicted that “teenagers will overlook the fact that this is routine entertainment and go for it in a big way” while “adult males will accept it” as the second half of a double feature. And Harrison’s Reports called it “an ordinary picture of its kind, offering little that will remain in one’s memory after he leaves the theatre”. The journal said that “the events leading up to [the] climax are generally unimaginative and contain little genuine suspense or excitement”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, British film scholar Phil Hardy writes that “the jungle sequences are full of suspense”, a statement that, together with a number of errors in his plot description, leads one to suspect that he wasn’t able to get a hold of a copy of the picture when writing the book.

Today, the film has a 4.6/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on just over 200 votes and not enough votes for a Letterboxd or Rotten Tomatoes consensus.

The film has a bit of a mixed reputation today, among the die-hard fans that look up these types of obscure B-movies. Glenn Erickson is dismissive in a write-up on Trailer from Hell: “In almost any monster film of the time we diehard fans can point to three or four great shots, the ‘good stuff’ that makes sitting through the rest of the movie worthwhile. Not here.” However, Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings is slightly more positive, as is Bruce Eder at AllMovie. Sindelar writes: “All in all, it would be pretty easy to dismiss this one, but the cast is likable enough, and I was in a congenial mood when I watched it, it was actually a little fun just to let the routine plot unfold in its own predictable way.” And Eder says: “the action, such as it is, does move along briskly, especially in the second half, despite some loose ends in the plot. And the science fiction side, when it finally gets here, is pretty neat — at least, it respects our intelligence more than the usual B-picture of this sort does. Gerald Fried’s sting-laden score helps immeasurably once the pacing notches up, and the performances are just good enough so that the ending, when it comes, is suitably dramatic and memorable, within the limitations of the script and budget.”

Cast & Crew

For more on producers Levy & Gardner, director Laven and writer Fielder, please check out my reviews on The Vampire (1957, review) and The Monster that Challenged the World (1957, review).

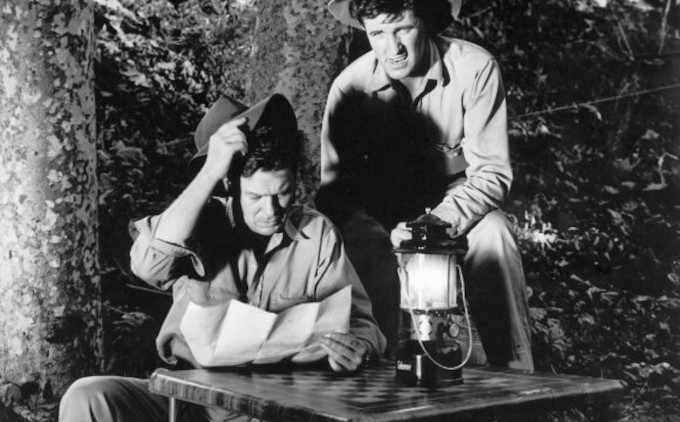

Male lead Arthur Franz had quite a successful career as a supporting actor in both B movies and A efforts like The Caine Mutiny (1954) and Sands if Iwo Jima (1949). He may be best remembered for playing the lead as a deranged murderer in The Sniper (1952). He appeared in a large number of science fiction series on TV and a few films, we have previously reviewed him on this blog in one of the major roles of the 1951 film Flight to Mars (1951, review) and as the adult lead in Invaders from Mars (1953, review). He also appeared in The Flame Barrier (1958), Monster on the Campus (1958, review), The Atomic Submarine (1959), in all of which he played the lead. He also narrated King Monster in 1976.

Kathleen Crowley had a background in theatre in New York, studying under the legendary Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. She had started her moving pictures career with leads in prestigious live-action TV shows in New York and worked for a year for MGM in Hollywood before starting to freelance in 1954. That’s when she got the opportunity to play the lead in Herman Cohen’s Target Earth (1954, review), opposite Richard Denning.

Crowley appeared in another sci-fi film, The Flame Barrier (1958), and did a few jungle and horror films, including the cult vampire western Curse of the Undead (1959). But she early segued back into TV, where she refused to take recurring parts in TV series, since she wanted to maintain her freedom, and often thought that the female parts in TV shows just weren’t good enough. Instead she made a good living out of appearing in TV movies and as a guest star on numerous TV series, with the odd cinematic movie thrown in here and there. When she gave birth to her first son, as late as 1970, she retired from the industry and never looked back. Weaver tells her straight up that he thought she was a very good actor and that her career could have gone further, and she tells him that back in the day, she wouldn’t do publicity, and that’s something she does regret; ”I thought it was what happened at eight o-clock the morning when the director said ‘action’ [that mattered], not who you was with at a nightclub the night before”.

Crowley didn’t have a great time on The Flame Barrier, as she complains to Weaver that co-lead Arthur Franz wasn’t a happy camper on B-movie sets, thinking himself above them.

I recently reviewed the British yeti film The Abominable Snowman, which features actor Robert Brown, who went on to fame as James Bond’s boss M. The Robert Brown in The Flame Barrier, however, was born in New Jersey rather than England. Bit-part and TV actor Brown is best known for playing the part of Lazarus in the first season of Star Trek, in the episode “The Alternative Factor”. Not so much for the role itself, but because he replaced John Drew Barrymore, who refused to show up on set for he first day of filming, and in a landmark court case, had his SAG membership suspended as a result. Brown spent most of his career in TV guest spots, until he was cast in the lead of the TV show Here Come the Brides (1968-1970) and Primus (1971-1972). Although the first was moderately successful, it didn’t do much to boost his career, which started teetering out towards the mid-70s.

Janne Wass

The Flame Barrier. 1958, USA. Directed by Paul Landres. Written by Pat Fielder, George Worthing Yates. Starring: Arthur Franz, Kathleen Crowley, Robert Brown, Vincent Padula, Rod Redwing, Kaz Oran, Grace Mathews, Pilar del Rey, Larry Duran, Bernie Gozier, Roberto Contreras, Dan Gachman. Music: Gerald Fried. Cinematography: Jack McKenzie. Editing: Jerry Young. Art direction: James Dowell Vance. Makeup: Dick Smith. Produced by Arthur Gardner & Jules Levy for Gramercy Pictures & United Artists.

Leave a comment