A makeup artist manipulates his actors to kill the studio brass that is shutting down horror movie production. AIP’s third and last teenage monster movie is a self-aware pastiche. The script makes no sense, but it is an entertaining romp. 5/10

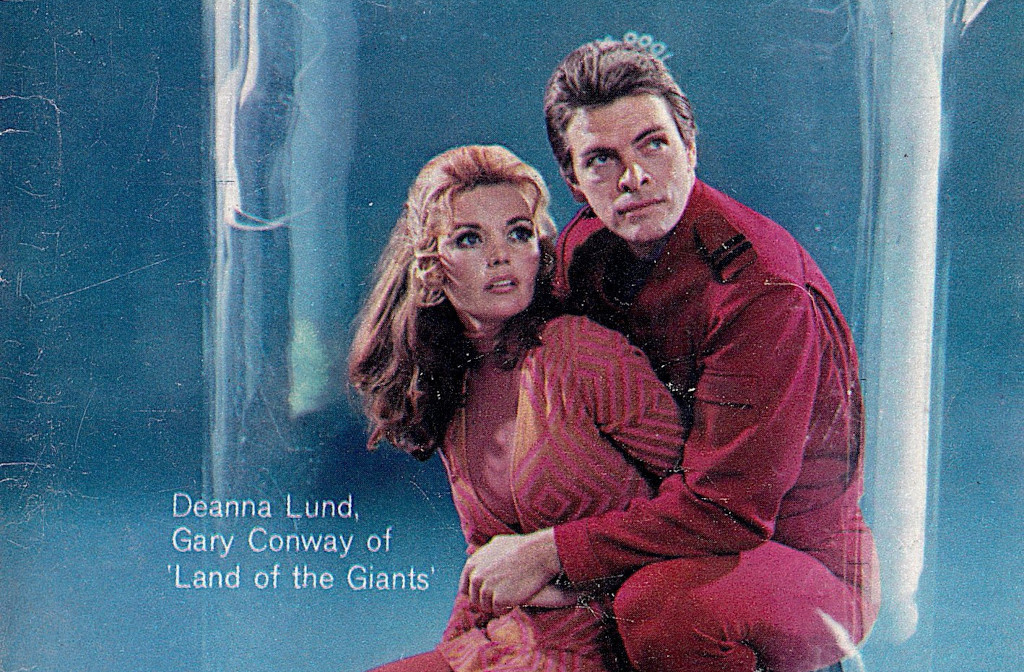

How to Make a Monster. 1958, USA. Produced & directed by Herman Cohen. Written by Cohen & Aben Kandel. Starring: Robert H. Harris, Paul Brinegar, Gary Conway, Gary Clarke. IMDb: 5.5/10. Letterboxd: 3.0/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

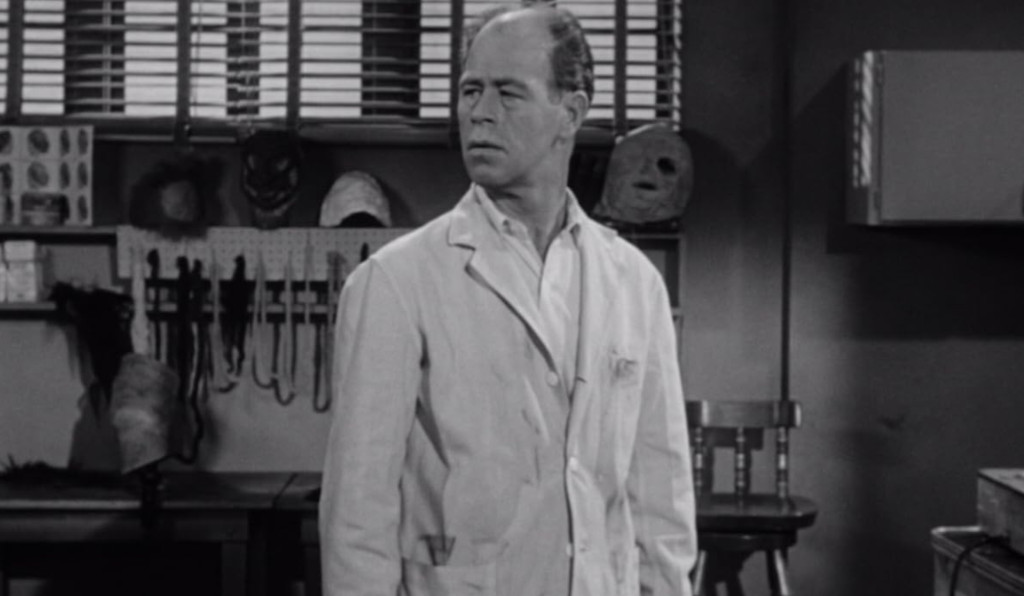

When a new regime takes over American International Studios, they inform long-time makeup genius Pete Dumond (Robert H. Harris) that they are shutting down the horror franchise in favour of musicals, and giving Dumond the boot as soon as he has finished work on the studio’s latest film, a monster mashup between Teenage Frankenstein and Teenage Werewolf. But Dumond won’t lay down to die quietly, and hatches a plan to bring the studio to ruin before he is done.

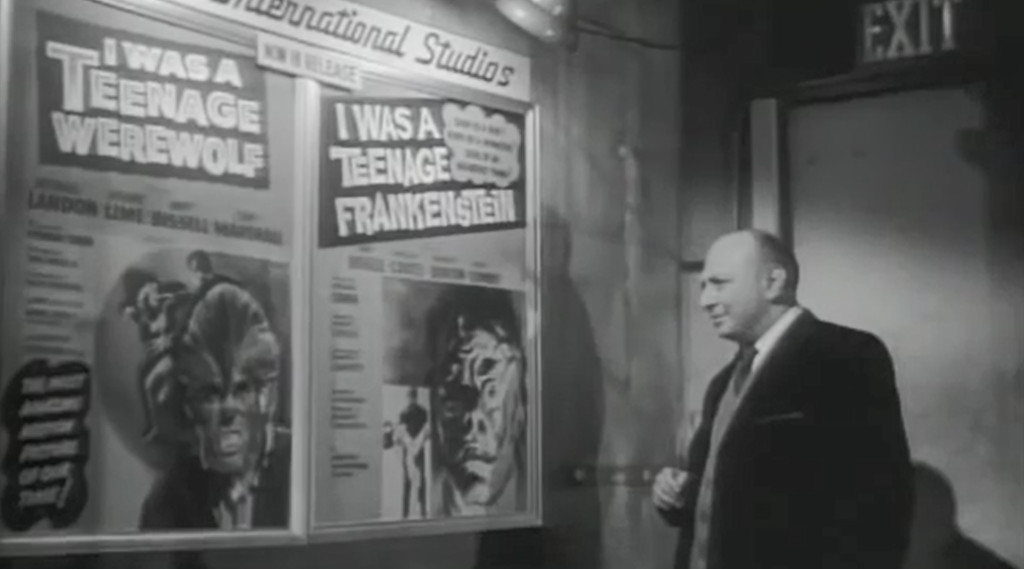

How to Make a Monster (1958) is a self-contained sequel of sorts to American International Pictures’ previous hit films I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review) and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957, review), although this time around, the monsters in the movie are simply creations of a make-up artist. The film was produced by Herman Cohen, who was also the brains behind the two previous films, and directed by AIP stalwart Herbert Strock. Almost the entire plot takes place at a fictional movie studio.

Dumond’s plan is to have the studio’s two new executives (played by Paul Maxwell and Eddie Marr) murdered by his own “creations”, Frankenstein’s monster and the Werewolf. The teenage actors playing the monsters in the studio’s films, Tony (Gary Conway) and Larry (Gary Clarke) are quite dear to Dumond, and he looks upon himself as a sort of minder of them – and looks upon the monsters he has created as his children.

Dumond explains his plan to his simple-minded assistant Rivero (Paul Brinegar): he has created a new makeup foundation that will allow him to put his monster actors under his hypnotic spell, and have them carry out his murderous deeds – in makeup – without remembering anything afterwards. The plot is then rather straightforward: Dumond has the two “monsters” kill the executives, and when an over-zealous security guard (Dennis Cross) starts suspecting him of the murders, he makes up himself as a third monster and bludgeons the guard to death. However, the police (with B-movie legend Morris Ankrum as the chief investigator) soon close in on Dumond and Rivero – and Rivero starts cracking up when intimidated by one of the investigators. After his last day at work, Dumond invites all three to a macabre “farewell party” at his house, where he has a candle-lit shrine dedicated to all of the monsters he ever created – his “children”. Without spoiling the ending, let’s just say that it all ends in a fiery finale where some monsters go up in flames and others survive to scare another day.

Background & Analysis

I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) was something of a stroke of genius by freelancing producer Herman Cohen, which managed to geniunely touch something poignant in the frustration of the young generation growing up in the US in the late 50s. At the same time, it was the first movie to successfully meld AIP’s two most popular genres – the teenage delinquent and the monster movie. Despite Cohen’s and Aben Kandel’s clunky and occasionally inept script, the film went deeper than usual on a subtextual level. The werewolf mirrored the pent-up teen angst and rage against adults unable to understand the new post-war generation, caught between the shadow of the cold war, with its nuclear angst and the new, sexually frivolous, consumerist culture. A generation born and raised in the Great Depression, who saw the best years of their lives devoured by the war, now pinning their hopes and dreams at their children, without ever asking what the teens themselves wanted. Gene Fowler provided good direction and future TV star Michael Landon shone in the title role, giving James Dean a run for his money. The film made $2,000,000 at the US box office, AIP’s best result to date. A follow-up was inevitable, this time featuring the Frankenstein monster, played by Gary Conway. While it has an interesting premise, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein is a much lesser film, although it was also a box office success. Why change a winning formula, thought Cohen and AIP, and produced a third movie, How to Make a Monster, this time a monster mash in classic Universal fashion. However this time it was firmly tongue-in-cheek.

Cult director Ed Wood’s widow Kathy Wood has claimed that AIP stole the idea for How to Make a Monster from him. According to Wood, he had previously presented a script with a similar idea to AIP exec Sam Arkoff. The script was written with Bela Lugosi in mind, and followed an ageing horror actor who decides to take revenge on a studio that sidelines him. However, Arkoff denied this, stating that he had nothing to do with the development of the script, and that the idea came straight from Herman Cohen. But knowing Arkoff’s reputation, one is inclined to err on the side of the Woods in this matter.

Whatever the case, Cohen’s and Aben Kandel’s script is both a mild attempt at satire on the movie business and an old-fashioned murder mystery plot. It also continues from its two predecessing movies the theme of an older mentor figure taking advantage of young men who have put themselves in his hands. However, the relationship between the youngsters and the mentor remains in the background of How to Make a Monster, focusing more on the machinations of Dumond, and to some extent on the relation between him and his assistant, and the way in which Dumond manipulates and deceives the feeble-minded Rivero. However, the themes are not explored in any depth.

Film scholar Bill Warren in his book Keep Watching the Skies! spends many pages analysing the film from an assumption that Cohen and Kandel used American International Pictures as a blueprint for the film’s movie studio – probably because they named the studio “American International Studios”. I think Warren makes too much of this, as there are few similarities between the fictional studio in the film and the real AIP. The film’s company is made out as a major studio, which AIP definitely was not. In fact AIP didn’t even have their own studio building, but shot their movies in rented spaces and on location. In the case of How to Make a Monster, they rented space at Ziv Studios, which primarily hosted TV productions. Cohen’s choice of name for the fictional studio was probably just a promotional stunt, in the same way that he shamelessly used How to Make a Monster to promote his two previous films as well as his upcoming one, Horrors of the Black Museum (1958).

It’s also questionable whether Cohen was making snide remarks about the state of Hollywood at the time. In fact, the monster movie witnessed a revival in the late 50s, thanks to the work of AIP and British Hammer Films, and not a decline. And if Cohen was serious about critizising the trend of music pictures, he probably wouldn’t have included a pointless musical number in the movie, just as all the other makers of teenage B-movies. If anything, the story seems to be inspired by the fate of legendary monster makeup artist Jack Pierce, who was forced out of Universal in 1946 after the new management pulled the plug on the monster franchise.

No, Cohen seems to mostly have been having a bit of a laugh at the expense of East Coast businessmen coming to Hollywood and “shaking things up”, believing they were on the cutting edge of the new trends, throwing out the baby with the bath water in their effort to make money off the movies. Cohen, who was born in 1925, was barely old enough to have experienced the golden age of Hollywood in any professional capacity, but he would have grown up with the classic Universal monsters as a kid, perhaps looking back at them with a sense of nostalgia – and the time when Universal was till the home of horror.

But most of all, this is an old-fashioned, light-hearted murder mystery and something of a pastiche on old monster movies – in a way it is Herman Cohen making fun of his own movies. How to Make a Monster is an early meta horror movie in that it is self-referential to the horror movie genre, anticipating such franchises as Scream (however, one could argue that a lot of the early old dark house films were also self-referential several decades earlier). It’s a fun glimpse behind the scenes in Hollywood, but a clearly fictionalised version of Hollywood, more akin to the audience’s perception of Hollywood than any reality. The film is full of delightful cameos by horror movie stalwarts. Early on we see Thomas Browne Henry playing a movie director talking Tony into the emotions of a wolfman scene, later we meet Robert Shayne as Tony’s agent, telling Dumand to leave his client alone. Morris Ankrum has a fairly sizeable role as the leading police investigator. John Ashley performs a pointless musical number, doing his best Elvis impersonation, surrounded by go-go girls. Ironically, he plays the musical artist set to drive out the horror movies from the business, but in reality, Ashley would himself become something of a Z-grade horror movie cult actor.

Of course, nothing much makes sense in the story. Why on Earth would Dumand want to have his actors running around in full makeup doing the killings? That’s like leaving a note at the crime scene shouting “It was me!”. Dumand was the only one present at the studio during two of the killings, and an eyewitness gave a clear depiction of his Frankenstein makeup at the third. Still, the police take ages to start considering Dumand as a suspect, when all evidence points straight at him from the beginning. Of course, this is just Cohen playing time. Why does Dumand himself dress up as a monster for the second killing? Like there would be a lot of monsters on a movie studio that didn’t emerge from the makeup room. And it’s very unclear what his motives are at the end — again, without spoiling too much: Dumand has spent the entire film trying to avoid being implicated in the murders, but his actions at the end would lead no doubt about the identity of the killer.

But all things considered, these flaws in logic matter little, because the film is made so clearly as a lark. Anyone expecting an actual horror movie will be quite disappointed. The science fiction angle is also minor – the only thing with an SF twist is the hypnose foundation, which is so silly it’s impossible to take it seriously.

Despite the fact that the plot treads water in the middle, the movie never gets boring. Enough things are happening to keep it moving, and Herbert Strock directs fairly fluidly. Strock may have been consigned to TV and B-movies for all of his career, but he was a competent, if pedestrian director. Strock seems to have had fun making How to Make a Monster, and while there are certainly a good deal of static scenes (the film was probably shot over a week on a budget of $100,00), there’s also enough camera movement and different camera angles as not to make the film stale. It also uses a gimmick that was becoming rather frequent with B-movies at this time, namely shooting the finale in colour. In this case, it was not just the final seconds that were in colour, as in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein and War of the Colossal Beast (1958, review), but actually the entire final 10-minute reel. This gives us a chance to see Dumand’s creepy home and his makeup creations (actually the creations of monster maker Paul Blaisdell), as well as the final flagration in colour. Strock made a handful of decent, even good, science fiction films in the 50s, and How to Make a Monster is up there with the better ones, if only because it is quite entertaining.

The iconic makeups for AIP’s werewolf and Frankenstein monster are naturally reused from the previous films. They were created by Phillip Scheer, and look just as good or bad as they did the year before. The werewolf makeup has always struck me as the better one, partly because it doesn’t suffer as much as the Frankenstein makeup from its rigidity. All the hair sort of cover up that it doesn’t really move much. The Frankenstein makeup, while gory, always looked like the mask that it was. It’s also difficult to reconcile the gory face with actor Gary Conway’s smooth, exposed arms. But of course, in this instance it doesn’t really matter how good or bad the makeup is, as it is supposed to look like makeup.

While the makeup was done by Scheer, the stuff we see in the final scenes, with all the monsters hanging on Dumand’s wall, was all done by AIP’s go-to monster maker Paul Blaisdell. Blaisdell wasn’t a makeup guy as much as a suit and props guy, and had a distinct spiky, cartoonish style to his creations, making them all difficult to take seriously. However, he was able to work wonders on the allowances that Roger Corman and others gave him. Most of Blaisdell’s work had been destroyed or was slowly falling apart already in 1958. They weren’t built to last, they were often modified for other movies and even when they were stored, they were often stored in poor conditions. But Blaisdell was able to cobble together a small gallery of monsters from his old films to be displayed in the final scene. For example, we see what was left of Beulah, the “cucumber monster” from It Conquered the World (1956, review), The Astrounding She Monster (1958) and one of the alien heads from Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review). We don’t see Blaisdell’s mask for AIP’s British import Cat Girl (1957), because it was placed behind the camera, but it was also infamously there. In the final scene, spoiler alert, we see Dumand’s “children” going up in flames. However, it wasn’t intended to burn Blaisdell’s old monsters, instead he made two new monster masks out of wax for the movie, which melt dramatically on screen, leaving human skulls behind. However, as fire and low-budget movies were often a dangerous combination, things didn’t go to plan, and the fire got out of control, singeing Beulah and completely destroying the cat girl mask. To add insult to injury, nobody was even filming the cat girl mask when it went up in flames.

How to Make a Monster succeeds because it is fun. The plot is as thin as it is silly and won’t stand up to any kind of logical scrutiny. Things happen simply because the plot needs them to happen. The characters are all one-dimensional cardboard cutouts. The direction is no more than adequate, neither is the acting – perhaps with the exception of Harris, who seems to revel in his rare lead. Paul Dunlap’s music is routine, as is the cinematography by Maury Gertsman. But the film moves at a nice clip, the actors all seem to have a reasonably good time, and the audience is constantly in on the joke. The movie doesn’t even set out to be smart or subversive, nor does it take the piss out of the 50s monster craze nor the teen movie. It laughs with its audience, not at it. Like all good spoofs, it is made with love for the subject-matter. It’s a minor movie and hardly a must-see for anyone. But if you chance upon it, chances are you will at least be entertained.

Reception & Legacy

I have not found any box office numbers for How to Make a Monster, but one would assume that its double bill with Teenage Caveman (1958, review) would have performed just as well as most AIP monster movies when it premiered in June , 1958 – that is, quite well. The Hollywood trade press also suggested that the pairing would satisfy the monster movie fans, and generally gave the film fair reviews.

Harrison’s Reports noted that the “story is novel and interesting”, and while “the picture […] is less horrific than the usual run of horror films”, the publication noted that it compensates this with “effective suspense values”. Like almost all trade publication reviews, Harrison’s Reports also noted favourably the switch to colour at the end. The Motion Picture Daily called the double bill “a natural for important box office returns”. The magazine called the meta angle “unique”. Variety wrote that the film is “more a mystery suspense picture than a horror item, and the horror effects are rather mild. The script has some sharp dialog and occasionally pungent Hollywood talk (‘That’s the way the footage cuts’) although these aspects will largely be lost on the audiences this picture will attract.”

As of writing, the films holds a 5.5/10 rating on IMDb, based on 1,500 votes and a 3.0/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on 1,250 votes.

TV Guide said about How to Make a Monster: “Silly, sort of stupid, but a lot of fun if you love old AIP movies”. Kevin Lyons at the EOFFTV Review writes: “How to Make a Monster is a bit of a mixed bag. It’s fun but it’s never quite the incisive Hollywood satire that one suspects Cohen and Kandel would have wanted to make”. Richard Scheib at Moria gives the movie 2/5 stars: “Unfortunately, How to Make a Monster is a film where the basic idea is more interesting than any of the delivery. Herbert L. Strock […] had a technical competence but is pedestrian – the film comes with no surprises or tension.” However, the film has its defenders, like Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum, who gives it 4/4 stars: “Man oh man; is this a brilliant film or what? It deftly updates the classic mad scientist premise into the Golden Era of Hollywood. Of course, instead of a mad scientist, it’s a mad make-up man. And if you loved I Was a Teenage Werewolf and Frankenstein, this movie is guaranteed to knock your socks off. What better way to get them together on screen than to have them running around the AIP back lot? It’s just pure genius.”

Several critics point out that How to Make a Monster was a transitional film for Herman Cohen – a halfway point between the teenage monster films he made for AIP and the horror mystery movies he was already starting to produce in England, which often involved serial killers – like The Horror of the Black Museum, which even gets advertised in this film. While AIP continued to combine horror and teenagers, How to Make a Monster was the last in this particular vein of teenage monsters. Roger Corman did direct Teenage Caveman, but the film had nothing to do with teenagers (lead actor Robert Vaughn was 26 at the time), and Corman’s working title was “Prehistoric World”. However, AIP exec Sam Arkoff changed the title without even informing Corman.

In 2001 effects wizard Stan Winston produced five TV movies under the banner “Creature Features” for Cinemax, all of them remakes – or really reimaginings – of old AIP horror/SF movies. In the case of How to Make a Monster, Winston only borrowed the memorable title, and the film has nothing to do with the original movie.

Cast & Crew

Producer/screenwriter Herman Cohen worked his way up the career ladder in the movie business from a young age — he began as a gofer in a movie theatre as a child and by the age of 15 he was well on his way to becoming a theatre manager. At the age of 25, in 1951, he produced his first film, The Bushwackers, and during the first half of the 50’s produced and sometimes co-wrote (often with Aben Kandel) around a dozen low-budget movies, including the abysmal Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (1952, review), and the slightly better post-apocalyptic thriller Target Earth (1954, review). In 1954 he was approached by James Nicholson who offered him to become a partner in the new movie company ARC, which later became AIP, but Cohen was tied up with obligations to United Artists. Nicholson instead founded the company with lawyer Sam Arkoff. Nevertheless, it was AIP that gave Cohen his greatest success, starting with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), and following up with I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), Blood of Dracula (1957) and How to Make a Monster (1958). He then relocated to the UK, where he produced such films as Konga (1961), Berserk (1967) and Trog (1970). He gradually moved more into distributing than producing, and in 1981 formed the distribution company Cobra Media. He passed away in 2002.

Screenwriter, Romanian immigrant Aben Kandel started his career as a novelist in 1927, and also began writing plays. His 1931 hit play Hot Money was turned into films in 1932 and 1936, and one of his short stories was filmed in 1934, and one of his novels in 1940. He wrote his first screenplay in 1935. He wrote over a dozen screenplays in the 30’s, 40’s and early fifties, when he began writing for TV and struck up his long partnership with Herman Cohen. He co-wrote most of Cohen’s movies, which is what he is best remebered for today.

Herbert Strock was a respected editor with some TV directorial experience when he was assigned to edit Ivan Tors’ and Curt Siodmak’s SF movie The Magnetic Monster (review). According to some sources, he took over directorial duties as Siodmak wasn’t comfortable with the technical aspects of directing. However, there are diferrings claims on whether or not this was actually the case. Strock also edited another Siodmak film, Donovan’s Brain (1954, review), and, according to himself, talked producer Tom Gries out of firing Siodmak. Here, Strock still ended up directing second unit. Strock did replace Siodmak when Siodmak had written and directed a TV series in Sweden, called 13 Demon Street (1959). However, when the episodes were finished, the studio thought most of them were too bad to release. So Strock got called in again, to re-edit three of them into a feature film called The Devil’s Messenger (1961).

Herbert Strock later ended up directing parts of Riders to the Stars (1954, review), again uncredited, when star and director Richard Carlson felt uneasy about directing the scenes he appeared in himself. The robot film Gog (1954, review) was Strock’s first credited feature film direction. He later directed a number of B horror and SF, like, Blood of Dracula (1957), I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), The Crawling Hand (1963) and Monster (1980), and he also wrote the latter two. He edited and produced a number of these films.

Robert H. Harris, born Robert H. Hurlitz in New York in 1911, was a respected character actor in film and TV, but his primary medium was the stage, where he appeared as an actor on Broadway and worked as both director and theatre manager off Broadway. From 1949 onwards he appeared regularly on TV, mostly in guest spots, often as sinister or evil characters. However, he achieved perhaps his biggest TV success as Jake Goldberg, a rare sympathetic character on the show The Goldbergs between 1954 and 1956. On the big screen, Harris appeared in around 20 films. He is perhaps best remembered in supporting roles in Elia Kazan’s America America (1963), Edward Dmytryk’s Mirage (1965) and Mark Robson’s cult classic Valley of the Dolls (1967). The latter has a surprising connection to How to Make a Monster (1958), as both films offers critical looks at show business. The later one just has a lot more sex. Harris also appeared in the SF kiddie film Invisible Boy (1957).

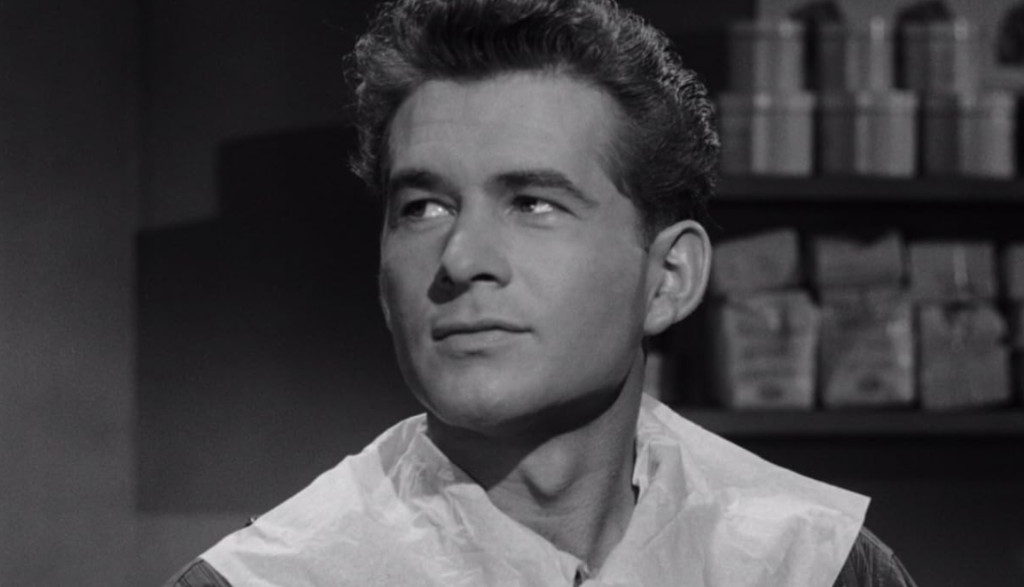

Gary Conway was an art student at UCLA who was regularly seen in University plays and worked as a bouncer in the evenings. He tells Tom Weaver that an agent had spotted him and suggested he go and seen AIP about a role in the upcoming The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Journey to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent (1957). He got a role, and on the strength of that, got cast as the creature in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. The studio apparently thought his real name, Gareth Carmody, was too refined, which suited Conway well, as he was a serious art student and didn’t feel like having the AIP movies coming back to haunt him in the future, so a change to Cary Conway was a good solution for both parties.

Conway reprised his role as the creature in the film’s follow-up How to Make a Monster (1958), but that was the end of his association with AIP. He transitioned to TV, where he did guest spots in a number of TV shows through the 50s and 60s, and continued to act sporadically in the 80s and 90s. He is probably best remembered for starring in the lead in the TV show Land of the Giants (1968-1969). Conway was married to Miss America 1957, Marian McKnight, and together then ran a winery, which they eventually sold for a decent profit. In latter years, Conway moved into the production and distribution side of the movie business, wrote a couple of films and even directed one in 2000. This remained his last movie project – to date. As of February, 2024, he is still alive at the respectful age of 88. While happy to have changed his name, Conway tells Weaver he feels very fondly about his old monster movies, and that, despite all their shortcomings, they have stood the test of time.

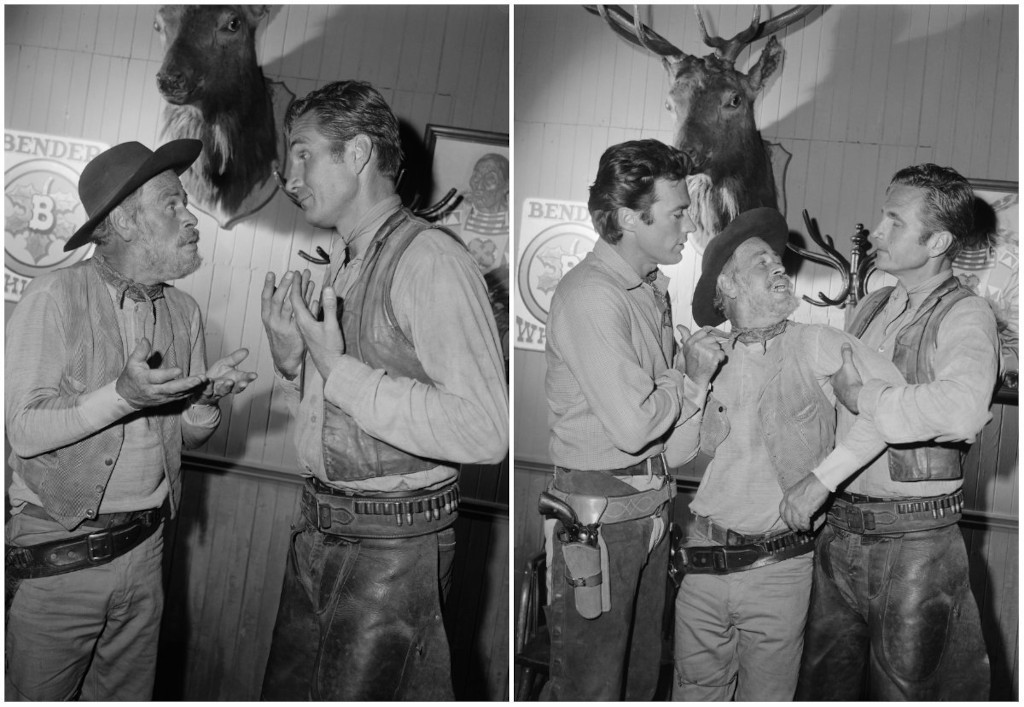

Gary Clarke took over the role of the werewolf from Michael Landon in How to Make a Monster. Born Clarke Frederic Lamoreux in Los Angeles, he was set on becoming an actor from an early age and started out in stock theatre, and did a few TV guest spots before landing his first lead role in film in AIP’s Dragstrip Riot in 1958, and went on to appear as co-lead in the studio’s How to Make a Monster (1958) and Missile to the Moon (1958, review). He then worked mainly in TV, most notably in a recurring role in The Virginian (1962-1964). He worked semi-steadily in TV and film throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s, and appeared in the big screen as recently as 2020. At the time of writing, Clarke is still in the books of the living.

Paul Brinegar was an in-demand character actor closely associated with the western genre, most notably because of his role of Captain Washington Wishbone in over 200 episodes of Rawhide (1959-1965). He appeared in a large supporting role in How to Make a Monster, and had a small but memorable bit-part in a fictional movie trailer doing a Clint Eastwood parody in the Leslie Nielsen space spoof The Creature Wasn’t Nice in 1981. He also appeared in World Without End (1956, review) and The Vampire (1957, review).

How to Make a Monster (1958) was the first science fiction film of Paul Maxwell, who was to become something of a staple in the genre, even if most of his credits are from TV shows. In particular, he became a fixture in the Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s marionette series. He was part of the principal voice cast of the Andersons’ second SF puppet series, Firebird XL5 (1962-1963). He appereared in one episode of the original Thunderbirds show (1965-1966) and was again among the principle cast of Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons (1967-1968). He voiced Captain Paul Travers in the movie Thunderbirds are GO (1966). Maxwell also had a large role in the Golem film It! (1967) and in James Cameron’s Aliens (1986) he played Paul Van Leuwen, the chairman of the tribunal set up to investigate what happened to the Nostromo in the original film. He might be best remembered for playing “the man in the Panama hat” who tells Harrison Ford he belongs in a museum in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

Further reading on SF staples Morris Ankrum, Thomas Browne Henry and Robert Shayne can easily be found through clicking the name tags in this sentence.

Janne Wass

How to Make a Monster. 1958, USA. Directed by Herman Cohen. Written by Herman Cohen & Aben Kandel. Starring: Robert H. Harris, Paul Brinegar, Garu Conway, Gary Clarke, Malcolm Atterbury, Dennis Cross, Morris Ankrum, Walter Reed, Paul Maxwell, Eddie Marr, Heather Ames, Morris Ankrum, Robert Shayne, Thomas Browne Henry. Music: Paul Dunlap. Cinematography: Maury Gertsman. Editing: Jerry Young. Art direction: Leslie Thomas. Makeup: Phillip Scheer. Sound: Herman Lewis. Wardrobe: Oscar Rodriquez. Produced by Herman Cohen for Sunset Productions & American International Pictures.

Leave a comment