Archaeologists recap their previous adventures with the resurrected Aztec mummy and battle a villain and his killer cyborg. The third instalment in the Mexican Aztec Mummy trilogy from 1958 uses up two thirds of the picture on stock footage from the two previous ones. 2/10

La momio azteca contra el robot humano. 1958, Mexico. Directed by Rafael Portillo. Written by Guillermo Calderón, Alfredo Salazar. Starring: Ramón Gay, Rosita Arenas, Crox Alvarado, Luis Aceves Castañeda, Ángel Di Stefani. Produced by Guillermo Calderón. IMDb: 2.4/10. Letterboxd: 1.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Dr. Eduardo Almada (Ramón Gay) and his wife Flor (Rosita Arenas) gather their old friends, including their associate Pinacate (Crox Alvarado), to bring them an update on their ongoing quest for the breastplate and bracelet of the old Aztec Mummy. While the group have previously successfuly battled the reanimated mummy Popoca and the devious Dr. Krupp, disguised as the villain The Bat, danger is once again afoot.

La momia azteca contra el robot humano (1958) or The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy is the third and last instalment in Guillermo Calderón’s and Alfredo Salazar’s trilogy concerning the reanimated Aztek mummy Popoca. All three movies were filmed back-to-back in Mexico in 1957, and released during 1957 and 1958. The film has a reputation as an unusually bad one, taken that most of it consists of stock footage from the previous two movies, The Aztec Mummy (1957) and The Curse of the Aztec Mummy (1957).

Dr. Almada begins his story by recapping the events of the previous two movies: How his experiments with regressive hypnosis revealed that his then-girlfriend, now wife, Flor, is the reincarantion of Xochitl, the lover of the ancient Aztec warrior Popoca (Ángel Di Stefani), who was mummified alive because of his love for Xochitl. It is rumoured that on the breastplate and bracelet of Popoca’s mummy, there are engraved in hieropglyphics the location of Popoca’s secret treasure, wich Almada sets out to discover.

The film follows the ancient Aztec mummification rituals and how Dr. Almada, Pinacate and Flor’s father Dr. Sepúlveda (Jorge Mondragón) set out to retrieve the trinkets with the help of Flor’s memory of her past life. However, they do not count on the fact that removing the artefacts from the mummy’s body functions as an alarm clock, awakening the undead warrior. They are also thwarted by the evil Dr. Krupp (Luis Aceves Castañeda), who is in reality the mysterious villain The Bat. After much sneaking about in dark crypts, all descend on the reanimated Popoca, who is invulnerable to bullets, and really pissed about being deprived of his belongings. Dr. Sepúlveda saves the day by holding off the mummy with a crucifix and then blowing up the crypt with dynamite, with both him and Popoca inside. Our surviving heroes then expose Krupp as The Bat, and the villain is taken into custody by the police.

But alas, in the second movie Krupp manages to escape the clutches of the police, and hypnotizes Flor into revealing the location of the mummy’s tomb. He kidnaps Flor and goes about fetching the artefacts, again awakening poor old Popoca, who really doesn’t like when you sneak off with his jewellery when he’s napping. However, Dr. Almada and Pinacate come to the rescue, aided by the mysterious masked superhero El Angel – who is revealed to be Pinacate. After some to and fro, the three heroes are captured by Krupp and held in his lab, awaiting death. But when all seems hopeless, Popoca the Mummy breaks into Krupp’s lab, throws Krupp in a pit full of snakes and again shuffles off back to bed with his belongings.

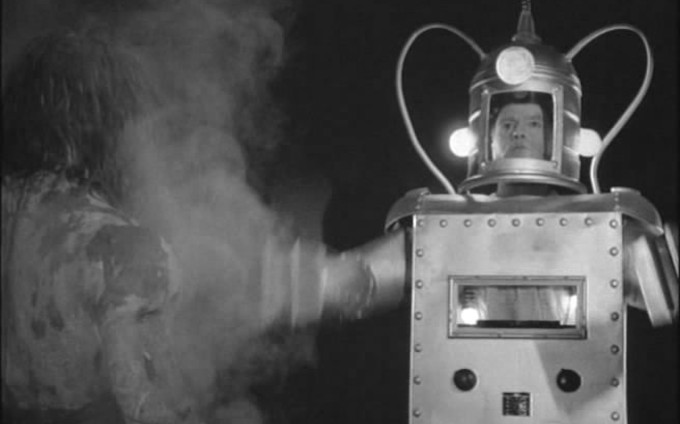

Now we are 45 minutes into the 65-minute movie, and everything up to this point has been stock footage from the previous films, alternated with new shots of Dr. Almada telling the story to his friends in a sitting room. Now, finally, we are up to speed, as Almada reveals that Dr. Krupp esaped the snake pit of the previous film through a trap door, and is once again on the hunt for the breastplate and bracelet. Almada and Pinacate trace suspicious shipments to Krupp’s lab, where they again manage to get caught by Krupp’s henchmen (they really should work on this stuff). Now Krupp reveals that he has been building a “human robot”, that is: a robot with the head and the brain of a human, which he hopes will be a match for the awesome powers of the mummy. Said and done, Krupp and his henchman Tierno (Arturo Martínez) once again break into the mummy’s tomb and steal Popoca’s trinkets, while leaving Almada and Pinacate back at the lab. When Popoca awakes once more, Krupp sets his robot on him. The robot seems to be winning, thanks to its powers of disintegration. But just when it seems that evil is winning, Almada, Flor, Pincate and the police burst into the tomb. Almada shoots the remote control from Krupp’s hands, disabling the robot, after which Popoca proceeds to rip the robot to shreds, and then descends on Krupp, who has now planted his last potato. Flor declares that for their love in a previous life, she hands over Popoca’s belongings, so that he can finally sleep in peace. The end.

Background & Analysis

I have not seen The Aztec Mummy, or The Curse of the Aztec Mummy, and several sources report that the best way to watch them both is to watch The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy, as this film basically gives you the entire plot of both previous films without all the boring downtime.

The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy was the brainchild of producer Guillermo Calderon and writer Alfredo Salazar. Both were renowned operatives during the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, which by 1957 was coming to a close. Neither had much experience with either horror or science fiction, although Salazar had penned the story for the horror movie La bruja (1954). Salazar was primarily known for writing comedy, and wanted to break out of the mold. The reasons for him choosing the horror genre may have been many, but most importanly, he must have been inspired by his brother, actor/writer/producer Abel Salazar, who in 1957 caused a sensation with his reimagining of Dracula in El Vampiro. This was the same year that Hammer reinvigorated the horror genre with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review), which also led to a renewed interest in the old Universal films.

Mexico has a long and proud horror history, starting in the early 30s, and we have reviewed a good handful of Mexican SF/horror pictures on this site as well. However, it wasn’t really until El Vampiro (1957) that Mexican cinema started tackling the hugely popular Universal monster movies head-on, turning Germán Robles into Mexico’s own Christopher Lee. Another inspiration was probably Ladrón de cadáveres (1957, review), in which luchador actor Wolf Ruvinskis starred as a sort of werewolf monster. That film also starred lucha libre film veteran Crox Alvarado, who turns up in The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy as Pinacate.

Vampire and werewolf movies having recently been released in Mexico, and there having been several films loosely based on the Frankenstein mad scientist trope, Universal’s The Mummy (1932) probably seemed like a logical next step for adaptation. Also, the action could easily be moved from Egypt to Mexico, creating a domestic brand, which would fit well into Mexico’s nationalistic film tradition. Salazar and Calderón weren’t going to be thwarted by the inconvenient fact that, unlike the Incas and the Mayans, the Aztecs did not practice mummification, but cremated their dead (and neither did they use hieroglyphs). The addition of the evil Dr. Krupp/The Bat is a trope that has bled into the movie from Hollywood film serials, which were just as popular in Mexico as the Universal monster movies. The pseudonym villain was already a trope in the fledgling lucha libre action movie genre, and in The Curse of the Aztec Mummy, the filmmakers went all out and added a luchador hero to the mix. Oddly enough, the fact that Pinacate is the luchador El Angel is completely omitted from the flashbacks in The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy — probably wisely, as it would have added yet another element to the already stuffed movie.

One of the main themes of the movie is hypnotic past life regression, inspired by the case of “Bridey Murphy”, or Virginia Tighe. In 1952, American housewife Tighe was put under hypnosis, during which she recounted her past life as a 19th century Irish woman called Bridey Murphy. Her story became a cultural phenomenon, and was turned into a book in 1954 and a film in 1956. In truth, The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy simply rehashes the idea presented in the original Universal film of the heroine of the movie being the reincarnated lover of the mummy — a trope that was in turn lifted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

For his choice of director, Calderón went to Rafael Portillo, a former editor whose editorial credits included work with distinguished directors like Luis Buñuel and Alfredo B. Crevenna, on the strength of which he emerged as a director in the mid-50s. Portillo had made his directorial debut in 1953, but had really only directed two films prior to The Aztec Mummy. It is possible that Calderón chose him primarily on his merits as an editor, knowing it would take a good editorial sense to shoot three movies at the same time.

For a film that uses two thirds of its running time on stock footage and recaps of two other movies, La momia azteca contra el robot humano is actually surprisingly coherent. This probably owes to the fact that all three films were filmed simultaneously, and planned this way in advance. In a way, one must applaud the audacity of Calderón and Salazar. It takes some cojones to release a trilogy of films where the third instalment is more or less a rerun of the two previous films. This is the sort of business wit that Roger Corman would have applauded (in fact, Calderón nicked the idea of making three movies back-to-back with the same cast and crew from his brother Pedro, who had done a similar thing in 1956, filming three musical comedies simultaneously). I have seen conflicting statements on the quality of the two previous movies, but all seem to agree that the entire story is pretty much contained within The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy, which makes me wonder just how much padding these two other films must have used to get their running times up to specs. Even in the third film, the scenes often feel stretched beyond their limits.

Inevitably, the plot is episodic, and especially during the first two thirds it grinds to a halt several times as we return to the sitting room where Almada narrates the recaps. The segments in between are often at least mildly engaging on their own, in the manner of 30s and 40s film serials, which is what this film mostly resembles, as is the case with many Mexican 50s action films. The short shooting schedule and low budget show in the filming: the movie is almost entirely shot in wide master shots and medium shots, with few cutaways, inserts or close-ups, and the cinematography is often static. The action scenes are hugely disappointing, considering the trilogy did involve a luchador hero (unfortunately cut from this movie). The brawls are completely without finesse, with opponents slugging each other in clumsy choreographies. The mummy does little more than hug people to death. The final fight between the robot and the mummy consists of awkward footage of two actors trying carefully not to destroy their fragile monster suits, resulting in something that mostly resembles slow-motion shoving match.

There are a few standout scenes, many of them involving Dr. Krupp, who is much livelier than villains in Mexican low-budget movies tended to be at the time. However, against the otherwise restrained and naturalistic acting in the film, he risks coming off as cartoonish rather than menacing, especially spouting the childish lines he has been provided with. Overall, the dialogue is painfully bad, with the actors spending pretty much the entire film either providing exposition or stating the obvious. Every line is designed to deliver information and none of it sounds like it was actually spoken by a human being. I have seen some comments online about the bad writing of the English dub, but as far as I can tell, the translation is pretty much a carbon copy of the original. A common problem with many of these Mexican SF/action films in the serial mold is that it is hard to find a character to sympathise with, and it isn’t helped by the fact that many of the actors are often former lucha libre fighters, rather than actual actors. This is not the case this time with lead actor Ramón Gay, but Gay isn’t able to elevate his role above its function as narrator. Retired wrestler Crox Alvarado usually brought a sort of moody gravitas to his roles, but he is miscast here as the bookish Pinacate (of course, there was a point to this when he was revealed as El Angel), and remains a wallflower. Intense Rosita Arenas gets a few moments to shine and makes the most of them, momentarily injecting the film with some emotional energy. As mentioned, Luis Aceves Castañeda hams it up to the max as Dr. Krupp/The Bat, and at least the scenes with him aren’t boring.

The production design looks cheap, and for the most of the time it is obscured by darkness – no doubt a budgetary measure. An exception is the early scene depicting the Aztec mummification ritual, involving a surprisingly large number of choreographed extras and reasonably extravagant costumes and sets. However, director Portillo is too fond of the scene, and it goes on several minutes too long. The mummy makeup and suit are OK for a low-budget movie, but Portillo doesn’t know how to shoot Ángel Di Stefani in order to give the monster the proper menace and mystery. It is mainly shot in unimaginative wide shots shuffling forward at a snail’s pace, in an overly stiff fashioned with its arms rigidly outstretched in an exaggerated Frankenstein fashion. What finally tips the film over into unintentional comedy is the “human robot”, which must be one of the worst robots ever put to screen this side of Robot Monster (1953, review). This looks exactly like what a 4-year-old kid would draw if you asked him to draw a robot, and poor Adolfo Rojas struggles to propel the ungainly costume without falling over (because the knees don’t bend). The thing even has a friggin’ light bulb attached to its forehead.

The one thing that makes this film, and its robot, interesting from a historical point of view, is that it marks (perhaps) the appearance of cinema’s first cyborg. The history of cyborgs in fiction easily becomes confused, as terms like robot, android, bionic and cyborg are sometimes used interchangeably. According to a very unreliable Wikipedia list, the first fictional cyborg appeared in Samuel-Henri Berthoud’s short story Prestige in 1831, but since I haven’t read it or found any synopsis of it, I can’t vouch for the accuracy of this statement. However, the story that is generally considered as the one introducing the cyborg to popular consciousness is Edgar Allan Poe’s The Man That Was Used Up (1839), about a soldier so badly damaged during the campaigns against the Native Americans that he has to be assembled every day from prosthetics and mechanics. Like in Poe’s story, most early mentions of cyborgs in literature were humorous or satirical, and it wasn’t until around the 1920s that serious literature on the subject started appearing, by authors such as Maurice Renard, Francis Flagg and Edmond Hamilton. By the 50s, the concept was fairly commonplace in SF literature, but had yet to be explored on screen.

Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz (1939) is arguably a cyborg, but since the story plays out in a magical fantasy setting where magical fantasy rules apply, it is debatable whether he should be considered a true cyborg. Some identify Maschinenmensch from Metropolis (1927, review) as a cyborg, but she is quite definitely an android – or actually a gynoid, if you want to use the correct terminology. (Also, beware of AI-written articles like this, where nine out of ten mentioned “cyborgs” are nothing of the kind). Nitpicking and semantics aside, 1958 was most likely the year that the science fiction cyborg made its debut on the silver screen. Two films contend for the title:William Alland’s and Eugène Lourié’s The Colossus of New York (review) andThe Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy. Which was first is a matter of which source you choose to believe. The Mexican film premiered in July 1958, and the US film has conflicting dates: Wikipedia states its premiere as June, 1958, while IMDb says November 1958. However, since it played on a double bill with The Space Children, it was probably released in June. Interestingly, both pictures include a human brain transplanted into a cumbersome robot.

The nods to both Mexican cinema and Hollywood horror are numerous, and sometimes absurd. The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy is like a bingo card of horror movie clichés. Of course, there are the obvious parallels to The Mummy (1932), but also many winks at the Universal Frankenstein movies. The mummy’s gait is copied from the later instalments of Universal’s Frankenstein franchise, and the robot is brought to life on the same kind of pivoting slab as the Bride of Frankenstein and the creature in many of the later instalments, with Dr. Krupp cackling away in typical mad Frankenstein fashion. And while the reincarnation theme is lifted from The Mummy, the way Krupp hypnotises Flor is straight out of Dracula (1931). In a flashback clip from the first movie in the trilogy, the mummy is inexplicably held at bay using a crucifix, although it is never explained why an ancient Aztec warrior would have any relation to a Christian symbol. The mummy also seems to shun daylight for no obvious reason. There’s a subplot in the films concerning a Krupp henchman whose face is deformed when the mummy throws him over a table with acid beakers. He spends the rest of the film hiding his deformed face with the lapel of his coat. Mexican horror movies had an obsession with facial deformation, going back to films like Herencia macabra (1940, review), Una luz en la ventana (1942, review) and El monstruo resucitado (1953, review). And then, of course, there’s also the lucha libre angle, which, unfortunately, is omitted from the third film.

Speaking strictly from a point of view of grading a film, you really can’t give a movie high marks when two thirds of it consists of stock footage from its two preceding entries in a trilogy. As opposed to other, better, cut-and-paste films, the stock footage isn’t even used in any creative manner, but simply recaps the story from the two previous entries, as an over-long “previously on the Adventures of the Aztec Mummy” segment. Even if one were to pretend that the two other pictures didn’t exist, The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy is an ungainly film. It has an episodic stop-start structure that, in combination with the long narration stretches, kills its energy repeatedly. Not that there is that much energy to kill, as the movie, despite being a condensed version of three different pictures, crawls along at a lethargic pace. It should not be possible to make a Mexican movie involving battles between lucha libre wrestlers, a revived mummy and a robot this dull. The dialogue is snooze-inducing and flatly delivered, and it really doesn’t matter whether you watch the Mexican version or the US dub. Both are equally poor. A few individual scenes and actors liven up proceedings from time to time, but it isn’t enough to save this thing. That said, if you are looking for a so-bad-it’s-good movie, then La momia azteca contra el robot humano is a prime choice!

Reception & Legacy

I have not found any Mexican reviews from 1958 for La momia azteca contra el robot humano, neither have I found any reviews from its 1964 US release.

Modern Mexican online critics seem to have oversight with the film’s flaws, regarding it as a little piece of domestic cult cinema. Julio Cesar Hernandez Pizano at Ciencia Ficción México writes: “[The] whole narrative mishmash results in a curious battle between traditional folkloric superstition (represented by the mummy) and growing technological fears (in this case the human robot). La momio azteca contro el robot humano is a cult work of national cinema that offers us an innocent vision of the applications of technology and raises concepts that would later become recurring themes in science fiction. It is worth giving it a chance.” Others seem to enjoy it for its badness. Oscar Arias at La Mansion del Terror says: “La momio azteca contro el robot humano is a really bad movie. Very bad, on every possible level, too. That’s why I had a good time watching it. […] The fact that it only lasts 65 minutes helps a lot to keep it from getting too boring, even with its slow and unnecessary scenes. But obviously it is what it is, it is only recommended for lovers of trashy movies.”

Many English-language critics seem to agree. Hal C. F. Astell at (re)Search My Trash writes: “Now whatever bad you want to say about this film is probably accurate […], but all of this is also a bit beside the point, as the film’s also pretty hilarious at pretty much every turn along the way, as its blend of horror clichés and cheap thrills in a slightly childish story without any sort of pretension has something weirdly hypnotic, so despite or maybe even for its shortcomings, this is a pretty entertaining movie.” Likewise Gary Loggins at Cracked Rear View Mirror said: “Okay, Citizen Kane it ain’t. The American dialogue sounds like something I would’ve written in 7th grade, with the worst dubbing east of Toho Studios. Some of the flashback shots are atmospheric, but most of the film is indescribably inept. You keep waiting for something to happen, and when it finally does, it’s a major disappointment. The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy is on many “worst of all time” lists, but to give it a tiny bit of credit, I liked Castaneda as the mad Dr. Krupp. And Flora’s not bad to look at. This film made me laugh, though. It wasn’t intended to provoke chuckles, but if you’re a fan of “so bad they’re good” twinkies, you’ll get a kick out of The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy.”

But there are also those who don’t find the film’s unintentional comedy is enough to redeem it. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Writings says: “Unfortunately, I find the movie sorely lacking in energy, and it has a static quality that gives it the feel of some of the very earliest talkies. In fact, there are stretches here where nothing is happening, such as the first few minutes of the robot resurrection scene, and cutting back and forth constantly between the characters staring at the robot on the slab does nothing to cover this up. As a result, watching this one is a bit of a chore.” Richard Scheib at Moria gives the movie a devastating 0/5 stars, writing: “Despite rehashing two other films, The Robot vs the Aztec Mummy lacks much interest dramatically. The direction is static and dull. There is a failure to invest anything in terms of atmosphere in the scenes with the mummy creeping about and menacing people. The most ridiculous thing about the twenty minutes of original footage that we get is the robot. […] At least, you hope, the showdown between the title creatures has something that looks forward to the various Godzilla vs ___ films of the coming decade. Alas, even then this is a fight that takes place inside a crypt and is over quickly”.

The film has a 2.4/10 rating on IMDb and a 1.8/5 rating on Letterboxd. It gained its current notoriety when it showed up on the first season of MST3K in 1989.

La momia azteca contra el robot humano was the last in the Aztec Mummy trilogy, even though “aztec mummies” did pop up here and there in later years. Alfredo Salazar returned to his mummy in 1964 with the lucha libre film The Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Mummy, and later legendary luchador Santo would battle mummies in films like The Mummies of Guanajuato (1972) and Santo in The Vengeance of the Mummy (1973). The Aztec mummy made a return in two low-budget luchador films in the 2000s, Mil Mascaras vs. the Aztec Mummy (2007) and Aztec Revenge (2015), as part of the Mil Mascaras revival.

The original The Aztec Mummy was bought up by schlockmeister Jerry Warren in 1963, and he shot new material with US actors, resulting in Attack of the Mayan Mummy. He did a similar trick with Curse of the Aztec Mummy, which he edited together with old scenes from La casa del terror (1959) and new footage featuring Lon Chaney, Jr. The result was the infamous Face of the Screaming Werewolf (1965). However, he did not get his hands on The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy, as the rights to that movie had been bought up by K. Gordon Murray along with a package of 70-something other Mexican genre movies, which he proceeded to dub in English and distribute in the US. These films were usually not tampered with, and the dubs tended to be true to the originals, albeit not always of the highest quality.

Cast & Crew

Producer Guillermo Calderón, along with brother Pedro, had behind him a distinguished career as one of the principle drivers of the so-called Rumberas film in the 50s. The Rumberas was a hugely popular genre of often urban melodrama infused with latin rythms, mostly centering around lower-class women such as prostitutes, barmaids and club singers and dancers. While it can be argued that the first examples of the Rumberas film emerged as early as the late 30s, it wasn’t until the 50s that the genre’s popularity exploded, partly thanks to Calderón’s films The Adventuress (1950), Victims of Sin (1950) and Sensualidad (1951).

By the mid-50s, the Rumberas film was losing popularity, partly because the genre had exhausted itself, and partly because of a new conservative government, which cracked down not only on the “immorality” of the Rumberas film, but also on the liberal urban nightlife which fed the genre. For Calderón, the decline of the Rumberas film was no insurmountable obstacle – he had been producing films in numerous genres since the mid-40s, and continued making crime films, urban melodramas, musicals, comedies and westerns. With a keen eye on what was happening in Hollywood, Calderón didn’t take long to latch on to what companies like Allied Artists and American International Pictures were churning out on minuscule budgets with reasonable success. With films like Los chiflados del rock and roll (1957) and Peligros de juventud (1960), Calderón tried to cater to a new, younger audience with a changing taste in culture. But he also ventured into the horror and science fiction genres which in Mexico at the time were becoming increasingly linked to the quickly emerging new craze: the lucha libre film.

For more on the birth of the lucha libre film, see my review ofEl enmascarado de plata (1954). The late 50s was the period when the luchador movie was starting to emerge as a sort of domestic superhero alternative in Mexico. The genre really exploded in 1961 when the superstar of Mexico’s lucha libre rings,Santo, decided, after many years’ hesitation, to lend his face to the screen. Around 150 luchador films were produced during the genre’s heyday in the 60s and 70s, and some of the most legendary were the products ofGuillermo Calderón and Alfredo Salazar. It was these two who introduced the infamous “wrestling women” in movies likeLas luchadoras contra el médico asesino (1963), The Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Mummy (1964), The Panther Women (1967) and Wrestling Women vs. the Murderous Robot (1969). Likewise, it was Calderón and Salazar who wrote and produced the hilarious cult classic The Batwoman (1968), in which a very sexed-up version of Bob Kane’s iconic comic book character meets the lucha libre world. Calderón struck gold when he produced over half a dozen Santo movies, several of which are among the most regarded of the wrestling star’s movie career – many of these were also written by Salazar. During his “golden years” in the horror and lucha libre genres, he also producedThe New Invisible Man (1958, review), the oddball Christmas movie Santa Claus (1959), in which Merlin and old Nick thwart the devil’s plans to ruin Christmas, the lost world film La isla de los dinosaurios (1967) and the infamousNight of the Bloody Apes (1969), which in its export version included a multitude of bare boobs, footage of real open heart surgery and bad gore effects. With the decline of the luchador genre and the Mexican horror genre, Calderón once again landed squarely on his feet, and began producing rather innocent sex comedies and melodramas with titles like Juventud desnuda (1971), Bikinis y rock (1972), Bellas de noche (1975) and Las modelos de desnudos (1983). He retired in 1994, and passed away in 2018.

As stated, Rafael Portillo started his career as an editor in the early 40s, and became a favourite of musical comedy director Ismail Rodriguez, but made his name in the early 50s, editing for Luis Buñuel and Alfredo B. Crevenna, which opened the doors for directorial duties. As a director, he primarily made B-movies, often comedies and melodramas, but occasionally strayed into the horror field as well, and, along with Calderón, was not above directing a few sex comedies in the 70s. He was also occasionally used by independent Hollywood production companies as co- or assistant director on films shot in Mexico, including the killer shark movie originally titled Shark! (1969) starring Burt Reynolds, and the horror movie The Devil’s Rain (1975) featuring Ernest Borgnine, William Shatner, Tom Skerritt, Ida Lupino and even a young John Travolta.

Lead actor Ramón Gay is best remembered today for being shot to death by the jealous husband of movie star Evangelina Elizondo (whom we have reviewed in Los platillos voladores) in 1960. Gay was a well-employed minor star of the Mexican screen, a good-looking but somewhat bland leading man. He appeared frequently in musical comedies and melodramas, not seldom reduced to playing “the other man”.

Rosita Arenas has been described as one of the last divas of the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. Arenas was born in Venezuela, the daughter of Spanish actor Miguel Arenas. She made her film debut in 1950 and played leading roles in melodramas and comedies in the 50s. With the decline of the Golden Age, she started appearing more and more in mystery and horror films, and toward the end of the decade and the 60s also started appearing in lucha libre cheapos. Arenas appeared in four movies that can be described as science fiction: La momia azteca contra el robot humano, as well as three films featuring wrestling superhero Neutron: Neutrón, el enmascarado negro (1960), Los automatas de la muerte (1962) and Neutrón contra el Dr. Caronte (1963). She also starred in all three of Guillermo Calderón’s Aztec Mummy movies in 1957-1958. In Calderón’s Los Chiflados del Rock and Roll (1957) she also tried her hand at singing, performing three songs in the film. She retired after the horror movie The Curse of the Crying Woman in 1963, based on the Mexican folk legend of La Llorona, and produced by Abel Salazar. However, she made a comeback in 1987, appearing in hald a dozen film and movie productions in the 80s and 90s.

Crox Alvarado was born Cruz Pío Socorro Alvarado Bolado in Guadalupe, and was one of the pioneers of the rapidly growing lucha libre scene in the 30s. He made his movie debut in 1937, and mostly appeared in bit parts, but impressed producers and directors enough to quickly move beyond the brawler roles he was originally cast as due to his physique and athleticism. His breakthrough came with a leading role in the melodrama Naná (1944), oppositie Mexican Hollywood star Lupe Velez. By now Alvarado had left wrestling behind and focused on his work as a caricaturist and actor. The role won him a regard as a serious character actor and romantic lead.

Crox Alvarado’s next important step was accepting the role of male lead in the 1952 movie The Magnificent Beast (La bestia magnifica), in which he played opposite fellow wrestler Wolf Ruvinskis and “the Marilyn Monroe of Mexico”, Czech star Miroslava. In the film, he played a wrestler struggling up from poverty. Along with Huracán Ramírez, The Magnificent Beast ushered in the age of the lucha movie, with Alvarado as one of its biggest stars. In fact, there was a long-running rumour going around that Crox Alvarado and Santo were in fact the same person. That is, until the theory was shattered in 1968, when they played opposite each other in Atacan las brujas, and again in Santo contra Capulina (1969). He starred as the hero in the Aztec Mummy trilogy in 1957 and 1958; The Aztec Mummy, The Curse of the Aztec Mummy and The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy. Between 1952 and his death in 1984 he appeared in over a dozen lucha films, a couple of boxing movies, some horror pictures, countless westerns and stints in romantic dramas, musicals, comedies, historical pictures, etc, and also established himself as a stage actor. To an English-language audience he is best known for appearing in bit-parts in Jerry Warren’s The Face of the Screaming Werewolf (1964), starring Lon Chaney, Jr., and the TV movie Attack of the Mayan Mummy (1964), which were both edited together from the Aztec Mummy films. You may also have seen him as a police inspector in The Batwoman (1968).

Luis Aceves Castañeda, who plays the evil Dr. Krupp in The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy, was a renowned character actor during the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, often appearing in villainous roles. He was a favourite of Luis Buñuel, and appeared in six of his movies, including Nazarín (1959) and Simon of the Desert (1965), both considered among the best of Buñuel’s work. He also did many films with Emilio Fernández, including Pueblerina (1949), Salón México (1949) and the star-studded Reportaje (1953), which was presented at the Cannes festival. He appeared in the supernatural fantasy film Macario (1960), directed by Roberto Galvadon. It was the first Mexican movie to be nominated for an Oscar for best foreign language film. Castañeda did not appear in many science fiction, horror or lucha libre films. He played the evil Dr. Krupp/The Bat in the Aztec Mummy series in 1957-1958, and turned up as the villain in the non-SF Santo movie Santo vs. the Diabolical Brain (1963). He retired from film acting in 1965 to direct the theatre company he had founded. Castañeda received an Ariel award (the Mexican Oscar) for best actor in a minor role in 1952 (for Buñuel’s Mexican Bus Ride), and was nominated for best supporting actor in 1953.

Flor’s father, who sacrifices himself at the end of The Aztec Mummy, was played by the respected character actor and trade unionist Jorge Mondragón, whose career on stage and in film spanned nine decades. Although he appeared in numerous films and acclaimed stage productions, he is best remembered for his tireless activism for actors’ rights in Mexico, and was one of the founding members of the Mexican actors guild, for which he also served as secretary general. He was also a key figure in the unionization of both Mexican performing artists and the film industry. Mondragón appeared in minor roles in a number of science fiction and lucha libre films – including one of Mexico’s very first SF movies, Los muertos hablan (1935, review) and the terrible Buster Keaton vehicle Boom in the Moon (1946, review). He also had roles in The New Invisible Man (1958), Doctor of Doom (1963), Santo in the Wax Museum (1963), The Panther Women (1967) and Santo and Blue Demon vs. Dr. Frankenstein (1974).

Another veteran actor worthy of mention is Arturo Martínez, who plays Tierno, the scarred henchman, in The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy. Martínez appeared in close to 200 films between 1948 and his death in 1992, often in villainous roles. He had larger roles (or at least high billing) as a mad doctor in the weird western El regreso del monstruo (1959) and played a heroic archaeologist in the SF-tinged Indiana Jones ripoff Abriendo Fuego (1989). He also turned up in a minor role in the Hollywood cult classic The Black Scorpion (1957, review).

Ángel Di Stefani was an Italian-born, tall, athletic bit part actor who often did roles that required some kind of stunt work in Mexican movies between 1944 and 1974. His role as the Aztec Mummy in the Aztec Mummy trilogy (1958-1959) is by far his most famous one, even though he appeared under heavy makeup in much of the movie. The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy was the only film appearance by Adolfo Rojas, who plays the titular robot.

Wrestlers Jesús Velázquez (Murcielago/The Bat), Guillermo Hernandez (Lobo Negro) and Firpo Segura all appear in the The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy (1958).

Janne Wass

La momio azteca contra el robot humano. 1958, Mexico. Directed by Rafael Portillo. Written by Guillermo Calderón, Alfredo Salazar. Starring: Ramón Gay, Rosita Arenas, Crox Alvarado, Luis Aceves Castañeda, Jorge Mondragón, Arturo Martínez, Ángel Di Stefani, Adolfo Rojas. Music: Antonio Díaz Conde. Cinematography: Enrique Wallace. Editing: Jorge Bustos. Production design: Javier Torres Torija. Makeup: Carmen Palomina. Produced by Guillermo Calderón for Cinematográfica Calderón.

Leave a comment