Arguably Argentina’s first horror movie proper, A Light in the Window from 1942 feels like an amalgamation of every old dark house film made in Hollywood in the twenties. Horror icon Narciso Ibáñez Menta stars as the acromegalic mad doctor kidnapping trespassers in order to perfect a cure for his condition. Cheap and derivative, but not terrible. 4/10

Una luz en la ventana. 1942, Argentina. Directed & written by Manuel Romero. Starring: Narciso Ibáñez Menta, Irma Córdoba, Juan Carlos Thorry, Severo Fernández, Nicolás Fregues, María Esther Buschiazzo. IMDb: 6/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Una luz en la ventana, translated as “A Light in the Window” is often cited as not only Argentina’s first science fiction film, but arguably the first horror movie made in the country, although that is a matter of some debate. A strong contender is the bizarre low-budget monstrosity El hombre bestia (1934, review). However, while it did make back its measly production costs many times over, that film was made as an independent cheapo and and was never picked up for distribution in Buenos Aires, the centre of the Argentine cinema business, so it has remained an obscurity. Una luz en la ventana, on the other hand, was made within the confines of the Argentine studio system proper, and has become something of a cult classic.

Argentina is historically one of Latin America’s three biggest movie producers, alongside Mexico and Brazil. The first Argentinian short film was made in 1897, and the country had a fairly strong comedy and documentary tradition in the silent era. Like in so many other countries that had previously been swamped by foreign productions, Argentina’s movie industry entered a Golden Age with the coming of sound in the thirties, to a large part because it was now necessary to produce movies in the audience’s own language. But for Argentinian film, there was also another benefit of the talkies, namely that the country’s strong musical tradition was now allowed to wash over the movie screen. This was the birth of the tango film, a genre that would more or less drown out all other genres of Argentinian cinema, save perhaps comedy. Tango films were usually romantic dramas or movies showcasing Argentinian culture and tradition, even if some of them also had more serious plots. But the emphasis on music, dance and comedy also left little room for experimentation with genre film, with the exception of the western, as the gaucho of the Pampas could easily replace the American cowboy.

Argentina has never had a strong tradition in cinematic science fiction: Barring a few US productions relocated to Latin America for budgetary reasons in the eighties, Argentina produced only around a dozen SF pictures during the entire 20th century. Una luz en la ventana can also be classified as SF only by the narrowest of margins.

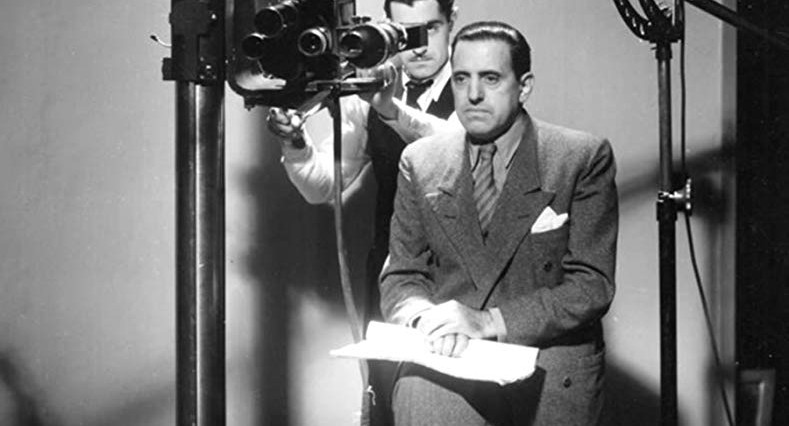

The country’s horror scene did eventually pick up, but primarily on TV, partly thanks to one of the actors on this movie, Narciso Ibáñez Menta. But in the forties only two horror films were made, with the inclusion of Una luz en la ventana, even if director Manuel Romero did direct a handful of thrillers, some of which borrowed elements from the horror genre. Romero was an extremely prolific writer and director with a background in stage work. He wrote over 180 plays and 50 films, and directed at least 53 pictures. While not the most critically lauded or commercially successful of his contemporary directors, he was known as an efficient filmmaker who could turn out acceptable movies as great speed and cost-efficiency. According to Tim Bernard and Peter Rist’s book South American Cinema: A Critical Filmography, Romero trained in the US-owned Spanish-language studios in France in the thirties. According to the book, Romero “worked in — and in Argentina often pioneered — a number of genres”. I’m guessing that the authors are referring to the director’s pioneering work in the horror genre, but perhaps also the police thriller. Una luz en la ventana came at the height of both the Golden Age of Argentinian cinema, and Romero’s own career, when he was churning out at least four pictures a year.

The plot of Una luz en la ventana is a classic an old horror film as you can get. Angélica (Irma Córdoba) arrives at a small town in a rainstorm, where she is supposed to take up a position as a nurse to an old, paralysed woman in a creepy remote estate. She gets a ride with two friendly men, romantic hero Mario (Juan Carlos Thorry) and his friend, comic relief character Juan (Severo Fernández). En route they crash their car, but walk to the estate where they see a light in a window, and are greeted by a giant, mute valet (Pedro Pompillo) and a creepy butler (Anibal Segovia) — as well as the similarly creepy Mrs. Herman (María Esther Buschazzio). After a few complications they are all invited to stay the night, but Mario and Juan smell a rat among all the creepy inhabitants, and rightly so, as Ms. Angelica is abducted during the night, and taken down to the basement laboratory of Mrs. Herman’s son, Dr. Herman (Narciso Ibáñez Menta).

It turns out that Dr. Herman suffers from acromegaly, a disorder caused by an excess of growth hormones, which causes extremities like cheekbones, ears, nose, hands and feet, to continue to grow even after the rest of the body is fully matured — resulting in some degree of deformity. Sometimes gigantism occurs. Dr. Herman has hidden away from the world and assisted by a Dr. Roberts (Nicolás Fregues) has developed a cure. The catch is that the procedure requires the extraction hormones from the pituitary gland from a living human. Now he has abducted Angélica in the hopes that she will perform the duties of nurse during the operation. Although reluctant, she has no choice but to agree after the heroic Mario barges in and manages to get himself captured, thus giving the villains both a “donor” and a hostage with which to blackmail Angélica (who has naturally fallen in love with Mario, as you do in movies during a car ride).

This setup raises a number of exciting questions: Will the dimwit Juan be able to convince the police that a mad doctor is about to perform dangerous experiments in his lab? Will Angélica be able to convince the desperate Dr. Herman that there is love for him in the world, no matter what he looks like? Will the hero actually do anything heroic in this film, apart from crashing his car and getting caught? And, most importantly, how are the filmmakers going to fill the remaining 50 minutes of the movie’s running 70-minutes time? And finally, what is the intended word that YouTube’s automatic English subtitles keeps translating as “prickly pears” throughout the entire movie?

The main problem with Una luz en la ventana is namely the fact that there really is no plot apart from the central premise of girl getting abducted by evil scientist in a creepy mansion. And unfortunately, girl gets abducted by mad scientist in creepy mansion around 20 minutes in. After this, the movie desperately treads water, trying to find the characters something to do. This is where comic relief Severo Fernández comes in, as writer-director Romero develops a long subplot in which Juan tries and fails to convince the police to arrest the mad doctor and hos gang, leading to much babble and two separate trips first to the police station and then to the estate. The need for comedy-filled padding is evident, however, already in the opening minutes of the movie, as a scene like Angélica hitching a ride with Mario and Juan, which could be done in a couple of minutes, is stretched out to ten because Fernández fills it with talk. This is an extremely talky movie, partly because very little happens in it. Fernández isn’t bad at what he’s doing per se, but in this film he is degraded to a sort of Mantan Moreland type spooked sidekick with little substance to his comedy, so he just stretches out the minutes, mainly by talking about how scared he is.

As is, oddly enough, very often the case in these films, the nominal hero is completely useless. Juan Carlos Thorry is fine in the role, as are, as a matter of fact, all actors involved. But there’s only so much you can do with a character who has to be reminded by his comic sidekick to go to the police when his girlfriend is being held hostage by a mad scientist. Thorry would later go on to become one of Argentina’s most successful actors with a movie and TV career spanning six decades.

Most interesting in the movie are naturally the ghouls of the old dark house, beginning with Narciso Ibáñez Menta’s acromegalic Dr. Herman. The acromegaly plot is actually rather original, as it still hadn’t surfaced in Hollywood. PRC’s agromegaly horror film The Monster Maker (review) didn’t come out until 1944, and real-life agromegaly sufferer Rondo Hatton made a name for himself for playing the sinister “The Creeper” in a number of movies in 1945 and 1946. But apart from this, there is little originality in the dark goings-ons in Una luz en la ventana.

Una luz en la ventana is inspired by Mexican medical horrors such as El baúl macabro (1936, review) and Herencia macabra (1940, review). Unfortunately it doesn’t follow in the footsteps of these macabre movies. There is no suggestion of girls being dragged down to their death in the basement, and Dr. Herman even points out that he hopes that the hormone donor he has kidnapped will survive the procedure. Even the test animals in the film survive. In tone and plot, the movie more resembles the old dark house movies so popular in Hollywood from the early twenties onward, often comedies more than actual horror movies. There are even direct references to Universal’s 1932 classic The Old Dark House, where Boris Karloff plays a sinister mute butler. Karloff gets name-checked in the dialogue when the mute valet turns up in the guise of Pedro Pompillo. Plus, Romero has checked off all the trappings of the subgenre. From the young couple and the comic relief character having car trouble on a stormy night, the light in the window over at the Frankenstein place, the creepy butler, the mute valet, the stern matriarch, the creaky, dark house with its secret rooms and hidden pathways, etc. It’s all so by the book that in 1942 it would have been cliché to the point of passé even to an Argentinian audience.

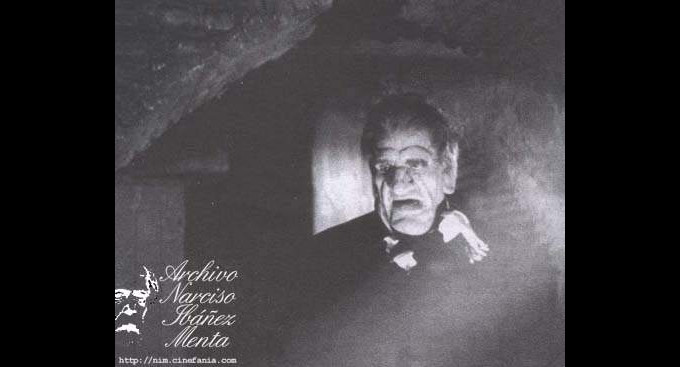

The highlight of the movie is, without doubt, Narciso Ibáñez Menta’s Dr. Herman, a character clearly inspired by The Phantom of the Opera, a tragic figure hiding his deformity and shame from the world, longing for a love he believes he can never have in his current state. Ibáñez Menta’s deep, deliberate and pained delivery adds weight and colour to the performance, and the fact that he spends most of the movie in backlight or sat in the shadows adds to the mystique. Ibáñez Menta was a Spanish stage actor who relocated to Argentina in the thirties, and Una luz en la ventana is perhaps best known for the fact that it was his film debut. Clearly drawn to classical horror roles, Ibáñez Menta played them on stage, but for obvious reasons didn’t have much chance to do them in the movies, as such movies weren’t made in Argentina, really before the sixties. It was on TV that he became a true horror icon, which is probably why he is so little known to a non-Hispanic audience. Here he took on the classic horror pieces from literature and the stage, not least in the hugely popular series Obras maestros del terror (1959) and Historias para no dormir (1966-1982). Apart from Una luz en la ventana, few of his films are of SF interest, however, he did do quite a bit of science fiction material on TV, both as writer and director and as an actor.

Ibáñez Menta’s love for the tragic title character of The Phantom of the Opera (which he had played on stage) is clear in this movie, and he saw himself following in the footsteps of the great Lon Chaney. Like Chaney, he did all his own makeup, and once even phoned up Boris Karloff to get makeup tips for Arsenic and Old Lace. The acromegaly makeup in Una luz en la ventana isn’t quite up to the standard of the great Jack Pierce at Universal, or even that of Ibáñez Menta’s idol Lon Chaney, but it’s slightly better, for example, then that of the later Mexican horror movie El monstruo resucitado (1953, review)), a film which bears a suspiciously strong resemblance to this one. The makeup here is rather crude, and makes Ibáñez Menta’s upper lip strangely stiff, but it serves its purpose and benefits from only being shown in short intervals. As John T. Soister and Henry Niconella write in the book Down from the Attic, the actor displayed his range and versatility in films, but really made a name for himself on TV, when he became the face of the horror genre in the fifties and sixties. He played everything from Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde to Dracula and The Phantom of the Opera — even Adolf Hitler. As a director, one of his favourites was Edgar Allan Poe, but he also did adaptations on stories by, for example, Ray Bradbury and Robert Bloch.

A contemporary review in Diario La Nación from 1942 gives the movie a sympathetic rating, commenting that the story unfolds “with agility” and that the movie raises the viewers heart rate and curiosity in “moments of comedy and intrigue”. The paper notes that the well-rounded supporting characters add to the proceedings, and are well played. However, the critics also notes that “the writer-director has been drinking from the material of Boris Karloff“, and thinks that Romero should perhaps stick to directing, as the screenplay is derivative and clichéd.

Modern reviewers are somewhat divided on the movie. Dario Lavia at Cinefania writes that “The ‘first horror film’ filmed in Argentina clearly demonstrates that in 1942 the country was at a stage of evolution similar to that experienced in the United States towards the end of the 1920s, when it was unthinkable that horror films would not have humorous sequences”. Lavia does praise the creepy atmosphere of the movie and the way the scenes with Dr. Herman are handled. However, Lavia also thinks that the excessive use the comedic sidekick ruins any suspense the film might have built up, and that the character is, on the whole, redundant. He gives the film a diplomatic 2,5/5 rating. He gets a reply regarding Severo Fernández’ comedy antics by Pablo Sapere at Zona Critica, who gives the movie a whopping 8/10 rating. While he agrees that the constant jokes sometimes take a toll on the atmosphere, he feels that the comedy material is mostly effective and even ahead of its time, as when it is being self-referential (in mentioning Boris Karloff, for example). Sapere writes that the movie is a “true classic of the golden age of Argentine cinematography and also kicks off the the fantastic cinema of the country”.

José Luis Salvador Estébenez at La Abadia de Berzano calls Una luz en la ventana “a nice and atmospheric film, which, when viewed from its correct historical perspective, has enough qualities to be enjoyable, beyond its eminent historical value”. Estébenez also points out that Ibáñez Menta, the Spanish immigrant, does the role with a strong Argentine accent, a sign of his devotion to his craft.

I think it is clear that Manuel Romero has not strived to create anything very unique here, other than an Argentine version of the classic old dark house tale. And as such, Una luz en la ventana succeeds admirably without impressing. Whether you like or dislike the subgenre’s uneasy marriage of horror imagery and verbal slapstick comedy will always be a matter of taste, but of course the comedy part can always be done better or worse. The auto-generated YouTube subtitles don’t give me enough information on how well it is done here, but the general impression seems to be that Severo Fernández isn’t necessarily bad, he just is overused, and his material spreads too thin. This, at least, is the impression I get, as many of the scenes involving his yapping seem to serve no other purpose than to pad out the movie. There is an awful lot of dialogue in this film for such a simple plot, and that’s not just counting Fernández. In fact, there’s so much talk that in the end even the mute brute starts babbling.

Manuel Romero’s direction is professional, but flat and static, and the low lighting, while mood-enhancing, not especially inventive nor artistic. I can find nothing in particular to either praise or critique in regards to the acting — all the actors play their assigned stereotyped cardboard cutout character as is appropriate in a film like this. Ibáñez Menta is the star of the movie and is very effective in his scenes, although I would have liked to actually see a little more of him — now it feels as if Romero hasn’t been convinced by the actor’s makeup, and does his best to hide it from the audience’s view. If you like to see Argentina’s “first” horror movie, Una luz en la ventana isn’t a horrible way to spend an afternoon (pun intended).

Janne Wass

Una luz en la ventana. 1942, Argentina. Directed & written by Manuel Romero. Starring: Narciso Ibáñez Menta, Irma Córdoba, Juan Carlos Thorry, Severo Fernández, Nicolás Fregues, María Esther Buschiazzo, Pedro Pompillo, Anibal Segovia, Geradro Rodríguez, Fernando Campos. Music: George Andreani. Cinematography: Alfredo Traverso. Editing: A. Rampoldi. Production design: Ricardo J. Conord, Francisco Guglielmino. Makeup: Berta Gilbert, Narciso Ibáñez Menta. Sound: Juan M. Sanchez, Ángel Savalia. Produced by Lumiton.

Leave a comment