Archaeologists awake the mummy of a lovesick gladiator at Pompeii, and discover the leading lady is the reincarnation of his lover. Edward Cahn’s 1958 low-budget clunker is competently filmed and has a better-than-average monster, but the talky and slow-moving script is hard to compensate for. 3/10

Curse of the Faceless Man. 1958, USA. Directed by Edward Cahn. Written by Jerome Bixby. Starring: Richard Anderson, Elaine Edwards, Adele Mara, Luis van Rooten, Gar Moore, Bob Bryant. Produced by Robert Kent & Edward Small. IMDb: 4.8/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Archaeologists at Pompeii uncover a body encased in the ashes of the city (Bob Bryant). En route to the Museum of Pompeii, the body comes alive and kills the driver, but returns to its petrified state as it falls off the truck. When it finally arrives at the museum, it is examined by a team of scientists, including Paul Mallon (Richard Anderson) his former girlfriend Maria Fiorillo (Adele Mara), her current suitor Enricco Ricci (Gar Moore) and her father Carlo Fiorillo (Luis Van Rooten) and occult expert Dr. Emanuel (Jan Arvan). Also, Paul’s current fiancée Tina Enright (Elaine Edwards), an artists, is dragged into the proceedings as her nightmares of the Creature seem to be coming true.

Thus begins Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), made as a double bill to, and by the same creative team as, It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review). The film was written by science fiction writer Jerome Bixby and directed by low-budget specialist Edward Cahn for United Artists.

While an investigation into the death of the truck driver is initiated by Inspector Rinaldi (Jan Arvan), the scientists dig deeper into the history of the petrified mummy. Found alongside the body is a box of Etruscan jewellery and a medallion with an inscription, identifying the man as Quintillus Aurelius, gladiator of Etruscan descent. Also inscribed on the medallion is a curse, seemingly predicting the eruption of Vesuvius, and condeming to death anyone who “stands between Aurelius and that which is his. That which is his, apparently, is Lucilla Helena, daughter of a senator, who was forbidden to marry him because of his lowly social status. In a twist that will surprise no-one, Paul’s fiancée Tina, who seems to have a strange connection to Aurelius, is the reincarnation of the ancient gladiator’s beloved.

However, this information only comes to us later, after Tina’s first encounter with Aurelius, when, after being forbidden to sketch him for her painting, based on her dream, she sneaks into the museum at night, strangly obsessed by the body, and Aurelius comes to life. Instead of heading for the door right behind her, Tina freezes and screams, and then faints, as women were prone to in 50s movies. Hearing her scream, the nightwatchman enters the room and, only to be killed by Aurelius after having emptied his revolver at the monster with no effect. Aurelius then takes a brooch that was found with him and pins it on Tina, after which he again becomes petrified.

When the rest of the gang arrive, Tina is in a state of catatonic shock. Paul is still sceptical about this whole ancient-gladiator-coming-to-life business and wants to take Tina home, but Dr. Fiorillo insists she has to stay in Naples. Fiorillo, drawing on his vast expertise in archaeology, explains that the key to curing shock is to expose the shocked person to that which shocked her in the first place. Realizing the brooch is of some importance, Fiorello, Paul, Maria and Enricco place the brooch near the mummy at night, and keep watch to see if it will come alive. Which it does. Paul tries to decapitate it with an axe, but the axe just glances off the crust skin. Paul is knocked unconscious, and Aurelius heads to Tina’s apartment – which by some strange coincidence happens to be the same place as Lucilla Helena lived.

Apparently, the mummy’s very slow shuffle is too fast for the gang, so they call Inspector Renaldi and ask him to post guard’s outside Tina’s apartment. When Paul and the gang arrive, someone, not entirely without reason, suggests that perhaps someone should stand outside Tina’s door, instead of having everyone hang around the street. But archaeologist Firorillo, who is an expert in shock, states that it would be harmful for Tina if the action took place so close to her apartment. Aurelius is grateful for this decision, and easily enters through the back door to the house, which no-one has seen fit to guard, and breaks into Tina’s apartment. Tina, now awake, is able to escape her apartment, and, standing in the hallway which leads to the back door and freedom, decided to instead escape into the basement with no way out. She is followed by Aurelius, but when he reaches Tina, he again turns immobile.

Aurelius is taken back to the museum and tied down. Dr. Emanuel, after digging through his books, explains the story of Aurelius and Lucilla Helena, and the fact that Aurelius caused the eruption of Vesuvius throgh his curse. He and Fiorillo, after long and arduous research, have come to the surprising conclusion that 2000 years ago, men would court women with jewellery, and are thus able to connect Tina with Lucilla Helena. Emanuel speculates that when Vesuvius erupted, Aurelius was on his way to court Lucilla Helena, and now in death, is trying to fulfill his mission. He then asks Helena to come with him to a place called The Blind Fisherman’s Cove, where Helena gets a flashback of the eruption of Vesuvius, and all the people trying to escape into the boiling waters. Emanuel then takes Tina to his home, and with the help of past-life regression hypnosis, is able to confirm, once again, that Tina is indeed the reincarnation of Lucilla Helena.

That same night, Tina, under some odd spell, again sneaks into the room where Aurelius is kept, and cuts his bonds. Paul visits her apartment, and sees that she has finished her painting – and has added herself cutting Aurelius’ bonds. When he arrives at the museum it is too late. Aurelius has kidnapped Tina, and is now headed to The Blind Fisherman’s Cove. Emanuel says that Aurelius is trying to fulfil the action that he was interrupted in during the day Vesuvius erupted: he is trying to save Helena from the eruption by carrying her into the waters. The gang and the police jump into their cars, but are unable to stop Aurelius from entering the sea, where Helena will no doubt be drowned. But lo and behold, Aurelius starts dissolving in the water, and Helena is carried out of the waist-deep water by Paul — this is the closest he comes to heroism in this film.

Background & Analysis

Curse of the Faceless Man (1958) was one of a handful of science fiction movies made for United Artists in the late 50s. It was produced by Robert E. Kent, who simultaneously produced It! The Terror from Beyond Space, through Edward Small’s Vogue Pictures – Small being a freelance producer with a contract with UA. Like It! The Terror from Beyond Space, it was directed by Edward Cahn, a low-budget specialist whose work with American International Pictures had impressed UA and Small. Not so much because of the quality of his work, but because he was able to make movies fast and cheap. It was also written by the same screenwriter who did It! The Terror from Beyond Space, Jerome Bixby – the double bill was his first screenwriting assignment.

Bixby has later stated that the story idea for Curse of the Faceless Man was handed to him, probably by Robert Kent. The story itself is basically a rehash of Universal’s The Mummy (1932). Both films open with what is essentially a mummy being uncovered, which comes to life and kills the person guarding it. Both mummies are called back to life in order to reclaim a lover which was denied them in their past lives, and both carry a curse that kills anyone who gets in their way. Both movies rely heavily on the plot element of a woman being the reincarnation of the mummy’s girlfriend, and who are at some point taken over by the spirit of said lover. Although I doubt there is any actual connection, Curse of the Faceless Man, oddly enough, has a very similar story as the 1958 Mexican movie The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy (review), as both deal with a mummy that gets very upset when someone steals its trinkets, and tries to get together with his old flame. Both also use past-life regression hypnosis as a plot point – although in the case of Curse of the Faceless Man it feels shoehorned into the story. The prevalence of this trope in the late 50s is explained by the case of “Bridey Murphy” – a US woman who under hypnosis claimed to be the reincarnation of a 19th century Irishwoman called Bridey Murphy. Her story was made famous first through a series of newspaper articles in 1954, then through a book published by the hypnotist in 1956, and a film released the same year by Paramount. By the late 50s, past-life regression hypnosis was a hot talking point.

Jerome Bixby, an author who dabbled heavily in science fiction in the 50s, wrote a reasonably tight and sprightly script for It! The Terror from Beyond Space. Unfortunately, it seems the the screenplay for Curse of the Faceless Man was cobbled together in extreme haste and with little enthusiasm. As stated, it is essentially a rehash of the old The Mummy trope, with the scorned ancient warrior returning to claim the reincarnation of his lost love. Unfortunately, the film lacks Boris Karloff, and Eddie Cahn is no Karl Freund. Nor is Bixby a John L. Balderston.

The thing that makes Curse fall into the category of science fiction, where The Mummy does not, is radioactivity. At one point, it is explained that the reason Aurelius is a dead-alive is the fact that when Vesuvius erupted, he was stealing jewellery for his girlfriend from an Etruscan temple, and in the commotion, he stumbled over the temple’s embalming liquids, which covered him at the same time that he was encased in lava, which was, apparently, radioactive. As Paul very much points out: radioactivity + embalming fluids do not a 2000-year old zombie make, but Bixby’s reasonable protest against his own screenplay is waved off by Dr. Fiorelli, who simply says that who knows what could happen.

And apparently, the missing ingredient was x-rays. It is explained at one point, that the x-rays used to examine the body is what brought it back to life. However, this does not explain how it came back to life en route from Pompeii, as there most certainly would not have been an x-ray machine amid the ruins of the lost city. It also does not explain why Aurelius keeps snapping back to life and then become petrified again. Also, we never get an explanation as to why Aurelius dissolves in the water. This blend of scientific and occult explanations for the existence of the monster creates some confusion as to whether the curse is a thing or not. The film goes out of its way to provide a scientific-sounding reason for Aurelius’ resurrection and undead existence, but it also makes it clear that the whole reincarnation business and love across the centuries is equally true.

If you want to nitpick science, then this film is a prime choice. There is hardly a single correct science statement in the entire picture, and screenwriter Bixby seems to be aware of how ludicrous some of his explanations are, as he often lets his characters throw their hands in the air and protest the bonkers pseudo-science they let out of their mouths.

Logic fares little better in Curse of the Faceless Man. For one, Aurelius seems not to be the sharpest tool in the box. He creates a curse that will destroy all of Pompeii, on the very same day as he is on his way to propose to Lucilla Helena, in the process – apparently – getting both him and his loved one killed. And instead of immediately going to save Helena from the eruption, he takes the time to raid the local temple for trinkets.

The plot of Curse of the Faceless Man also relies on the main characters making incredibly stupid decisions time after time, sometimes on extremely contrived motivations – like guarding only one of two entrances to Tina’s house and not having a single person guarding her actual apartment, or having Tina repeatedly freeze and faint when she could easily have escaped. It’s also bizarre that Tina, who does not work at the museum, and does not own a key, is able to just waltz into the building in the middle of the night and with no trouble get into the room where the museum’s most prized find is being stored — not only that, but a find that some of the scientists actually think might be responsible for murder. To make matters even worse, had all the scientists and police not interfered with Aurelius and Tina, almost all deaths in the movie could have been avoided. Had Aurelius just been allowed to carry off Tina to the sea, he would have dissolved and Tina could have swum ashore. No harm done to anyone.

The movie is also hampered by a staid jealousy/love quadrant plot line that goes nowhere. Enricco is jealous at Paul when he arrives, thinking he is going to steal back Maria, and Maria at one point seems to be interested in rekindling the old flame. However, nothing is ever made of this subplot, and it has no bearing on the plot itself, as there is no actual drama involved. This seems to be an addition to the script that’s there only to have some sort of personal drama amidst the mummy hunt.

This movie has perhaps the most unengaging romantic lead this side of Escapement (1958, review). Paul, nominally the hero of the film, does nothing throughout the entire movie except second-guess all his colleagues and arrive late to every situation. He refuses to listen to his wife, his superiors or the other scientists. The only thing remotely heroic he does in movie is wade out to pick up Tina from waist-deep water at the finale. It doesn’t help that Richard Anderson completely phones in his performance – there’s not a flicker of enthusiasm on his face during any of the proceedings, and he gives one of the dullest leading man performances we have ever seen here on Scifist. And we have seen a lot.

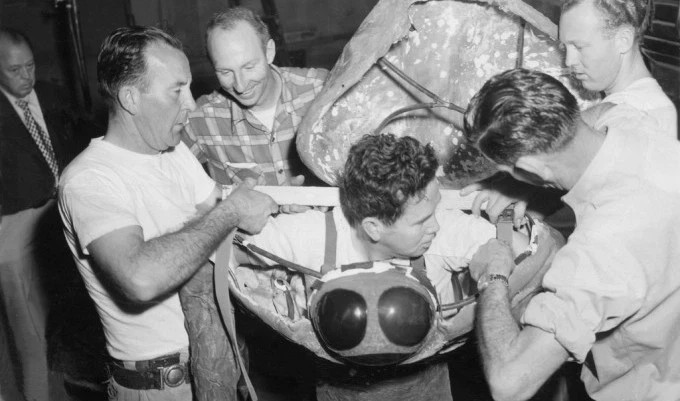

Elaine Edwards wins no acting awards for her portrayal of Tina, but she is quite good at acting scared, and has a nice scream, and belongs to the actors who get clean papers in this film. The same cannot be said for Adele Mara, who plays Maria. Mara was no newcomer – she had acted in movies for nearly 20 years, but she constantly looks like she is in desperate need of some direction. Gar Moore, playing her boyfriend, doesn’t really get anything much to do. Seasoned character actor Luis Van Rooten, here in a rare sympathetic role, carries the character of the quirky professor with some conviction, but but is hampered by the bad writing. Felix Locher as Dr. Emamuel, father of noted actor Jon Hall, got into acting by accident by the age of 73, and his lack of experience shows. He feels like he is reading his lines from a cue card. Jan Arvan as the police inspector is really the only one able to insert some energy into the proceedings, but his role is too small to help the film. Muscular Bob Bryant as the monster is suitably imposing.

The monster actually looks rather good, both in its immobile plaster prop version, and as a costume worn by Bob Bryant. For It! The Terror from Beyond Space, producer Robert Kent called upon the services of AIP’s go-to monster maker Paul Blaisdell. For Curse of the Faceless Man he went to another special effects royalty: Charles Gemora. Gemora had been around since the silent era, as a carpenter, set dresser, makeup artists, stuntman, ape and suit actor and special effects designer, on both prestige classics and B-movies. Among other things, he created the Martians for The War of the Worlds (1953, review).

The inspiration for the monster is taken from the iconic displays of the victims of the Vesuvius eruption. Of course, the white “bodies” on display are not bodies at all – no Egyptian-style mummies remained in Pompeii, only bones. They are merely plaster casts of the hollows created by the calcified ash that covered the bodies, after the bodies themselves decomposed. But Gemora has skilfully recreated these motionless plaster casts, and the result is quite effective, both the plaster version and the suit, especially as it is filled out with the imposing body of Bob Bryant. While drawing heavily on the mummies of movies past, it is a rather original monster, something that was not a given in the low-budget movies of the late 50s. It is also very well by Cahn and cinematographer Kenneth Peach, creating a good deal of suspense and atmosphere. The sequences with the monster are the best in the film.

On the other hand, the direction of Curse of the Faceless Man is one of Edward Cahn’s weaker ones. Cahn was a veteran who found himself a niche in the 50s after the decline of the studio system as a director for hire with small studios and independent producers of B-movies, because of his ability to get acceptable films made fast and cheap. His movies seldom showed any finesse or particular artistic ambition, but they were mostly serviceable as drive-in fodder and bottom-of-the-bill fillers. Curse of the Faceless Man has all the hallmarks of an Eddie Cahn movie: long, static shots with flat lighting and boring framing, a seeming lack of personal direction of the actors, the occasional flubbed line and actors who often feel like they are reading their lines from cue cards.

The film also has narration – however, sources differ on who provided it. According to IMDb, B-movie legend Morris Ankrum did the narration, while Wikipedia credits it to Vic Perrin. Narration in B-movies was a curiously common thing in the 50s, largely thanks to the popular TV series Dragnet. Sometimes it was used as an obvious method of patching up a holes in the script or connecting disparate scenes into a coherent whole. Other times the narration served no purpose other than the fact that producers and/or screenwriters thought it lended films some sort of gravitas or suspense. In these cases, the narration was often badly misused, telling audiences what they could already see happening on the screen, or information they were perfectly capable of figuring out themselves. The latter is the case with Curse of the Faceless Man, which has one of the most unnecessary voice-over narrations I have encountered in a long time.

Curse of the Faceless Man is fun whenever the monster comes alive. At all other times, it is a stale and slow-moving affair. The plot is thin and even for a 50s SF movie asks much of the viewer in order for them to suspend their disbelief. Fantastical proceedings are easier to swallow if you are emotionally swept up in the story, but when much of the film consists of people standing in a straight line, struggling to come to the end of their respective sentences, you have too much time to nitpick the screenplay. The film is a halfway acceptable programmer, saved by some atmospheric and even occasionally exciting scenes with an above-average 50s movie monster.

Reception & Legacy

Curse of the Faceless Man premiered in August, 1958 on a double bill wil It! The Terror from Beyond Space and made a good profit for United Artists, and opened in October the same year in the UK.

The film received mixed reviews in the trade press. British Monthly Film Bulletin was fairly positive in its 2/3 review: “This unpretentious film holds attention by straightforward presentation of its story. Its relation of character to surrounding is clearcut and uncomplicated, and it avoids overplaying of the sensational material”. The magazine also calls the monster “a charming addition to the catalogue of the screen’s abnormalities”.

Harrison’s Reports noted “praiseworthy efforts […] to present a novel theme”. However, the journal opined that the film, unfortunately, was only “moderately interesting”. According to the magazine, it’s main fault was that “most of the tale is unfolded by conversation, slowing up the action and tiring the spectator”. Jack Moffitt said: “A lot of thinking went in the Curse of the Faceless Man, and very little of it was any good”.

As of writing, Curse of the Faceless Man has a 4.8/10 rating on IMDb and a 2.9/5 rating on Letterboxd.

Online reviewers seem to be divided on the merits of the film. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings is definitely not a fan: “The dialogue started driving me crazy early on; it seems as if almost a quarter of the lines are on the order of “I’m sorry, but it’s been scientifically proven that dead men from two thousand years ago don’t stand up and walk around.” (Not an actual quote from the movie, but it might as well be.) And like too many mummy movies where the monster could be easily outrun, characters have to make immensely stupid decisions like standing stock still when the faceless man is coming at them, or running into a dead end where they can be cornered; I never find this kind of thing effective.”

On the other hand, Kris Davies at Quota Quickie is: “An interesting film that raises itself above the herd (though lets face it a lot of that herd are pretty terrible). The film is well constructed and paced. The monster scenes just edge the right side of the chills / cheese divide. The story has a little bit more intelligence than usual.”

DVD Savant Glenn Erickson notes that Curse of the Faceless Man “has all the necessary ingredients to motivate a potentially interesting monster movie” and “is too endearingly simpleminded not to find a warm place in the hearts of monster movie lovers”. However, he writes, “the mostly flat-lit sets look cheap, the dialogue is padded with irrelevant chatter and the unfortunate actors mostly stand rooted in place to read their lines. A droning narrator is heard at frequent intervals, re-capping the story and telling us what we’re seeing, as if nobody’s expecting us to pay attention. Worse, Edward Cahn’s direction creates very little in the way of mystique around the stone monster, which mostly looks like a mannequin covered with plaster.” Erickson concludes: “Pretty much near the bottom of the spectrum of real Hollywood filmmaking, it is barely feature-length, uses almost no sets and for thrills relies almost completely on a reasonably good monster costume.”

Cast & Crew

The producers of Curse of the Faceless Man was Robert E. Kent and Edward Small. Small started his career in production in the silent era and remained an independent produced throughout a career that lasted until 1970. However, in the early 30s, his production company struck a deal with United Artists, and Small produced several A-movies for UA during the 30s and 40s. In the 50s he was relegated to B-pictures and low-budget movies, until he ended up making straight-up exploiation in the 60s. Robert Kent was another independent producer, who started his career as a screenwriter. He eventually started doing films for Edward Small and United Artists, including It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review), Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), Invisible Invaders (1959), The Flight That Disappeared (1960) and Twice Told Tales (1961), starring Vincent Price.

Although not nearly as well-known to a mainstream audience as Ed Wood or Roger Corman, Edward L. Cahn is synonymous with the 50’s subgenre of so-bad-they’re-good Z-movies. Cahn began his career in the films as early as 1917 as a production assistant, and soon graduated to editing at Universal. Eventually, he became one of the studio’s top editors, before switching to directing in the early thirties, “turning out cheap and cheerful crime melodramas and comedies”, according to an IMDb bio by I.S. Mowis. Pretty much flying below the radar at Universal and MGM, he struck out as a freelancer in 1945, with much work but little recognition, making B-movies and shorts for various companies.

However, after a dry spell in the early 50’s, Cahn was back with a vengeance, now with his eyes set on the minor studios that were producing B-movie quickies for a teenage audience, like Columbia, Allied Artists and not least AIP. Cahn was hired to make movies that called for little artistic flair, but a steady directorial hand by someone who agreed to work fast, cheap and didn’t care too much about the end result, as long as there was a comprehensible film in the can, which could be sold to indiscriminate teenagers on the power of the poster alone. Not quite as prolific as Corman, Cahn still churned out at half a dozen films, sometimes more, each year between 1955 and his death in 1963. He became a go-to guy for crime thrillers, westerns and horror movies, with a seeming knack for zombie films. But he also made more traditional teen or “rock and roll” movies, as well as girls-in-prison films. His science fiction films include Creature with the Atom Brain (1955, review), Voodoo Woman (1957), Invasion of the Sauce Men (1957, review), Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review) and Invisible Invaders (1959). Best known of these is probably It! The Terror from Beyond Space, on the merit of it being one of the many works to inspire Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). This was also perhaps his best movie of the era.

Screenwriter Jerome Bixby, born 1923, was a writer of short stories as well as screen and teleplays. Although he is best remembered for his work in the field of science fiction, only 300(!) of his 1200(!) short stories are SF. During the early 50s, he briefly worked as an editor for a handful of magazines, including Planet Stories, Jungle Stories and Action Stories. Bixby was an extremely prolific writer of primarily western, SF, fantasy and horror stories. His perhaps best remembered and regarded story is It’s A Good Life (1953) about a small boy with godlike powers, who keeps his small community in terror. It was adapted for one of the most well-regarded episodes of The Twilight Zone in 1961. Bixby also wrote five episodes for the original Star Trek series in the 60s, including “Mirror, Mirror”, in which a transporter malfunction swaps Captain Kirk and his command crew with their evil counterparts from another dimension. It is generally regarded as one of the best shows in the series. Bixby wrote the screenplays for It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958) and Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), and contributed to the story of Fantastic Voyage (1966). The last work based on his material was The Man from Earth (2007), the script of which he finished on his deathbed in 1998, and is a fixup script based on several of his stories. The SF Encyclopedia writes; “Bixby’s work is professional and imaginative, but he clearly wrote too hurriedly and all too often excellent ideas fail to generate memorable stories”.

Lead actor Richard Anderson made his screen debut in 1949, and quickly impressed MGM talent scouts enough to offer him a contract. He had a succession of good supporting roles opposite many of the studio’s big stars, and appeared, in, among others, Forbidden Planet (1956, review) as one of Leslie Nielsen’s crew members. By the time the film premiered, his contract had been terminated and he struck out as a freelancer – and incidentally appeared in The Search for Bridey Murphy (1956), the film that helped create the “past life regression hypnosis” craze in the movies in the late 50s. Having appeared in such films as George Sidney’s Scaramouche (1952), Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) and Martin Ritt’s The Long, Hot Summer (1958), one can understand why he wasn’t quite firing on all cylinders when he played the lead in the clunky low-budget SF/horror movie Curse of the Faceless Man in 1958.

Anderson was a much better actor than his performance on Curse of the Faceless Man suggests, and he soon became a well-employed working actor on TV, with occasional stints in movies, such as Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion (1959), John Frankenheimer’s Seven Days in May (1964) and Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). However, his most famous role came when he was cast as Oscar Goldman, the boss of the titular US government cyborg agent in the smash hit TV sries The Six Million Dollar Man in 1974. The show ran for four years, and he reprised the role in the spinoff The Bionic Woman (1976-1978) and in a handful of TV movies.

Female lead Elaine Edwards‘ acting career stretched from 1949 to 1969 in relative obscurity. During most of the 50s she alternated between uncredited bit-parts in B-movies and guest spots on TV. The Curse of the Faceless Man (1958) gave her her first lead, and she played another one in Allied Artists’ Battle Flame (1959) and also appeared in United Artists’ Guns Girls and Gangsters (1959), best known for starring Mamie Van Doren and Lee Van Cleef (1959). She also appeared in a supporting role in AA’s old dark house film The Bat (1959), starring Vincent Price. In the late 50s and early 60s she got her best – or at least most prominent – roles in movies produced by Robert Kent and directed by Edward Cahn. By the mid-60s, her opportunities started to dwindle, and she ended her career with the futuristic low-budget sex comedy The Curious Female (1969), the only directorial effort of production manager Paul Rapp.

Adele Mara once had slightly bigger marquee draw, although her presence in a film like Curse of the Faceless Man is as good a sign as any that she was rather a long way from the A-list. Born to Spanish parents in Michigan in 1923, she began dancing and acting at a young age and made her Hollywood debut for Columbia in 1941. She had a few co-starring roles in bigger pictures, but her exotic look and her Hispanic accent made typecast her as leading lady in a number of B-westerns. However, her stint at Columbia was short, and in the mid-forties she moved to Republic. The studio dyed her her platinum blonde, creating a signature look for Mara, and she became a fixture in the studio’s B-westerns, while occasionally branching out to other genres. Her most prestigious role was probably that of John Agar’s love interest in the John Wayne vehicle Sands of Iwo Jima (1949). However, her contract with Republic also ran out in 1953, after which her film career started drying out, and she found herself mainly doing TV guest work. She retired in 1962, but did occasional guest spots in TV shows produced by her husband Roy Hoggins. Curse of the Faceless Man was her only SF film.

Handsome Gar Moore was appearing on stage in New York in 1946 when he was spotted by Roberto Rosselini’s talent scout, and made his film debut the same year in a small role as an American soldier in Rosselini’s Paisà. He did two more films in Italy before returning to the US, but had little luck in Hollywood. He consequently retired from acting in 1959 and took up a career as a painter and writer.

Felix Locher, who plays Dr. Emanuel in Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), had no designs to become an actor at his mature age of 73, when he visited his son, actor Jon Hall on the set of Hell Ship Mutiny in 1957. However, the director convinced him to play the part of the elderly Tahitan cheif. He caught the bug, and for the next 12 years appeared in close to 40 films or TV shows, including the Star Trek episode “The Deadly Years”, in which he played a member of a science team caused to age rapidly.

Composer Gerald Fried was nominated for an Oscar, six Emmys and won one Emmy, for his work with Quincy Jones Roots (1977). An oboist and composer, he moved to Hollywood in the early 50’s, invited by Stanley Kubrick. Fried scored Kubrick’s first five films, including his breakthrough, Paths of Glory (1957). Apart from his work with Kubrick and on Roots, Fried is probably best known for composing music for Star Trek, in particular the percussion and brass heavy “The Ritual/Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah”, for the scene in the episode “Amok Time” (1967) in which Spock and Kirk engage in a deadly duel. The piece, often dubbed “Star Trek Fight Music”, has been reused in several episodes and TV films. Fried kept composing almost up until his death in February 2023.

Art director William Glasgow had a checkered career. He designed both low-budget clunkers like Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957, review), Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review) and Invisible Invaders (1959), as well as Robert Aldrich’s Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1963) and Hush…Hush Sweet Charlotte (1965), for which he was nominated for an Oscar.

Filipino émigré Charles Gemora started out in Hollywood as a sculptor, working on many silent films for Universal, such as Phantom of the Opera, The Thief of Bagdad and Noah’s Ark, before using his talents to design gorilla suits for films. He realised that his short stature made him perfect for playing gorillas, so he donned the suits. He played gorillas or apes in nearly 60 films, becoming universally known as The Gorilla Man. He appeared as a gorilla in high profile films such as Gunga Din, Around the World in Eighty Days and The Ten Commandments. Apart from this, he also, possibly, played the alien in I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958, review).

But Gemora was also a talented makeup and special makeup man, working on such films as The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Double Indemnity (1944), Around the World in 80 Days (1956),Witness for the Prosecution (1957) and The Ten Commandments (1956). Gemora also created makeup, costumes and special effects for numerous science fiction movies. He made the apeman suit for The Lost World (1925, review), and the makeup and masks for the beast men in Island of Lost Souls (1932, review). He famously created the martians for The War of the Worlds (1952, review). He also worked onThe Cyclops (1940, review), Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), The Colossus of New York (1958, review) and I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958).

Among Charles Gemora’s many horror and fantasy credits can be mentioned (excluding the above-mentioned) Seven Footprints to Satan (1929), Ingagi (1930), The Monster and the Girl (1941), The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake (1959), Flight of the Lost Balloon (1961), Jack the Giant Killer (1962) and Hands of a Stranger (1962).

Special effects creator Ira Anderson, Jr. worked on such films asMissile to the Moon (1958, review), Frankenstein’s Daughter (1958, review), Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966), Tarzan and the Great River (1967), The Deep (1977), Damien: Omen II (1978), The Abyss (1989) and the TV series The Invanders (1967-1968). For Damien: Omen II, he was nominated for a Saturn Award.

Janne Wass

Curse of the Faceless Man. 1958, USA. Directed by Edward Cahn. Written by Jerome Bixby. Starring: Richard Anderson, Elaine Edwards, Adele Mara, Luis van Rooten, Gar Moore, Felix Locher, Jan Arvan, Bob Bryant. Music: Gerald Fried. Cinematography: Kenneth Peach. Editing: Grant Whytock. Art direction: William Glasgow. Makeup: Layne Britton, Charles Gemora. Special effects: Ira Anderson, Jr. Produced by Robert Kent & Edward Small for Vogue Pictures & United Artists.

Leave a comment