As an astronaut accidentally sends a mega-meteor on a collision course with Earth, scientists frantically work to find a way to save the planet. Italy’s first serious SF talkie from 1958 is an equal collection of hits and misses. The fairly intelligent script and Mario Bava’s atmospheric direction and photography make it worth a watch. 5/10

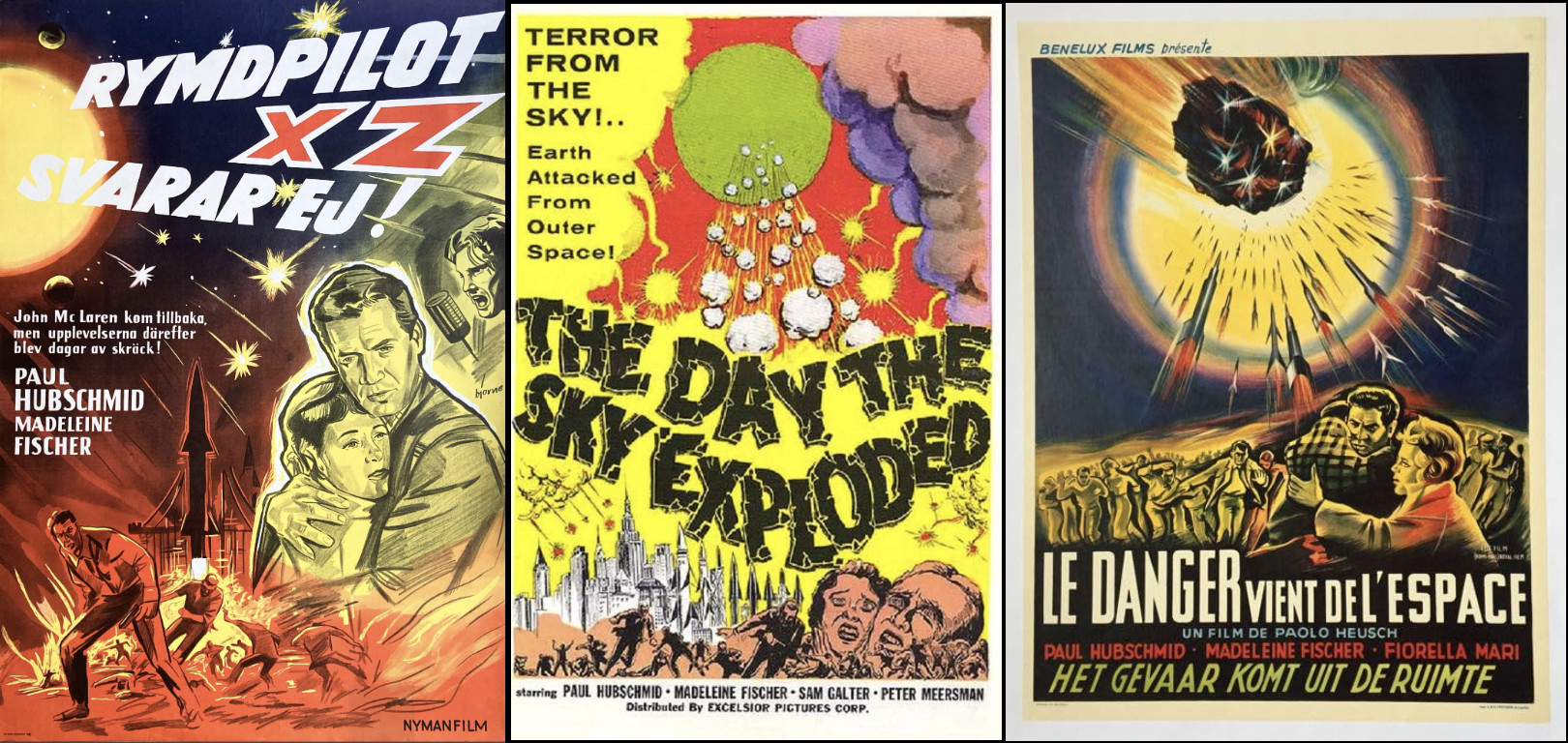

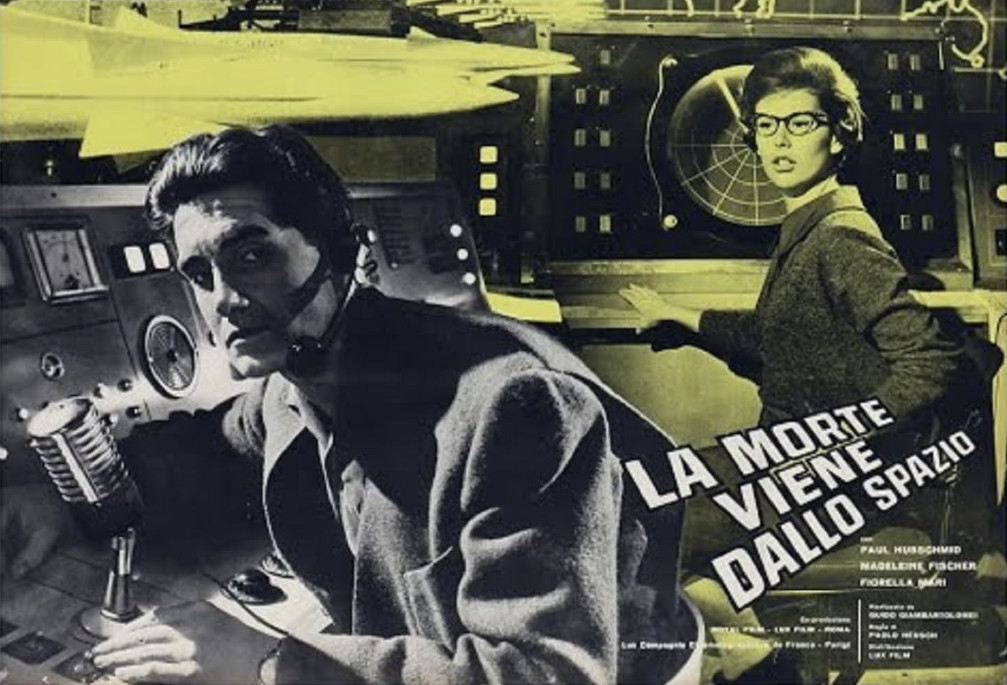

La morte viene dallo spazio. 1958, Italy. Directed by Mario Bava & Paolo Heusch. Written by Virgilio Sabel, Marcello Coscia, Sandro Continenza. Starring: Paul Hubschmid, Madeleine Fischer, Fiorella Mari, Ivo Garrani, Dario Michaelis. Produced by Guido Giambartolomei. IMDb: 4.5/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

The international community holds its breath as humanity is to send the first man in orbit around the moon. Backed up by an international team of scientists, the hero of the hour is American John McLaren (Paul Hubschmid), who leaves behind a wife, Mary (Fiorella Mari), a son, Dennis (Massimo Zeppieri) and a dog, Geiger. The launch goes perfectly, and celebrations break out among the science team based at Cape Shark, Australia, including Russian Sergei Boetnikov (Jean-Jacques Delbo), American Katy Dandridge (Madeleine Fischer), German Herbert Weisse (Ivo Garrani), French Peter Leduq (Dario Michaelis) and presumably Eastern European Randowsky (Sam Galter). But amidst toasts of champagne, McLaren sends out a distress signal: something has gone terribly wrong.

So starts La morte viene dallo spazio, Italy’s first serious science fiction talkie, directed, uncredited, by cinema legend Mario Bava. The 1958 film was made on a small budget and is famous for its ample use of stock footage. In 1961 it was dubbed and released in the US as The Day the Sky Exploded.

What has happened is that the rocket has malfunctioned, and McLaren has detached his cockpit from the nuclear-powered booster and returned to Earth. However, due to a communications error, no-one has turned off the booster, which speeds towards an asteroid cluster. As the booster explodes, the asteroids are dislodged from their orbit, and grouped together into a Godzilla meteor, which is now headed straight for Earth. As it nears, there’s great atmospheric upheavals, hurricanes, tsunamis and fires, and all the world’s coastal areas are ordered to be evacuated.

Scientists scramble to find a solution to the problem – a big problem indeed, as the jumbo meteor will smash the Earth to pieces if it hits. Key personnel in this mission are Ms Dandrige and Mr. Leduq, as they are the mathematicians in charge of the international space center’s computor – or calculator, as the English dub calls it. For a while the scientists pin their hope on the possibility that the meteor will brush the moon on its way towards the Earth and change direction. But as the giant rock barely misses the moon, and only hours remain before it strike our planet, things kick into high gear.

Meanwhile, personal drama plays out among our ensemble. Leduq, the smooth Frenchman, tries to hit on his colleague Dandridge, but she, being a woman scientist, is cold as a refrigerator, and keeps things strictly business. It doesn’t help that she overhears Leduq instigating a bet that he will be able to seduce her before the mission is over. McLaren and his family are headed home to the US, but tensions snap when the scientists discover the mega meteor and he decides to stay in Australia to help out. Mary explains that she can’t live like this anymore, with John constantly choosing his work over his family, and tells him that she is taking Dennis home. He asks her not to let the door hit her on the way out.

Back at the space centre, panic is starting to spread as scientists fail to come up with a way to save Earth. Amidst it all, Randowsky snaps and goes bonkers, and starts raving that the scientists all have theirselves to blame, for creating yet another nuclear rocket, and in their hubris have sent it into space. But Randowsky’s ravings actually give McLaren an idea: The multitude of nuclear missiles in the world might actually save humanity, if everyone agrees to cooperate and blast the meteor out of the sky. However, this would require precise calculations and cooperation. It will require Leduc and Dandridge to work out the exact launch coordinates and timing for every single nuclear missile in the world, and they need to relay these to every country in possession of nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, temperature rises on the Earth as the meteor closes, putting the computer’s cooling system to the test. It doesn’t help that Randowsky continues throwing wrenches in the wheels. Feeling that Earth being destroyed is righteous judgement for humanity’s warring ways, he grabs a gun and turns off the “air conditioner”, swearing to shoot anyone who tries to turn it on again. As the minutes count down, it’s a race against the clock for the other scientists. Will they be able to overpower Randowsky in time, and use the missiles created for man’s destruction for its salvation? Or will we meet our judgement in a flaming inferno?

Background & Analysis

La morte viene dallo spazio, or Le danger vient de l’espace, is an Italian-French co-production filmed in Italy, and produced by one of Italy’s most prestigious film company’s, Lux Film, where both Carlo Ponti and Dino de Laurentiis cut their teeth (however, by 1958 both had left the company). It was nominally directed by Paolo Heusch, but several cast members have testified to the fact that Heusch did very little on set, and that it was actually cinematographer Mario Bava who directed the movie. The literal title of the film means “Death comes from space”, but it was released in the US and UK as The Day the Sky Exploded.

The Day the Sky Exploded has been described as Italy’s first science fiction film. This is a somewhat dubious claim: several science fiction movies had been made in Italy prior to 1958, although many of them are lost today. The first movie dealing with SF elements was probably the 1910 short film An Interplanetary Marriage (review), even if one should probably label it as proto science fiction due to its whimsical nature. However, Marcel Perez’s feature film Le avventure straordinarissime di Saturnino Farandola (1913, review) should most definitely be considered a science fiction movie, in the vein of Jules Verne’s stories. Three films that can all probably be considered science fiction were made in Italy in 1921: Un viaggio nella luna, Il mostro di Frankenstein (review) and L’uomo meccanico (review). The two first movies are completely lost and the third partially lost. The first one we know little about apart from its title, meaning “A voyage to the moon”. From the second, nothing remains but a couple of stills and a few short reviews, but it appears to be an adaptation of Mary Shelley’s famous novel. Of the third, a 26-minute fragment exists, and the story concerns a villain who builds a murderous robot, and plays out in a style reminiscent of American film serials. The Day the Sky Exploded wasn’t even the first Italian science fiction talkie. Another film that seems to be either lost or unavailable was Stasera sciopero (1951), a screwball comedy based around the concept of a brain transplant.

There is little information on the background to The Day the Sky Exploded. It is unclear what prompted Lux Films to produce a serious science fiction movie, as it was something the studio had never done before. Neither the writers, producers or directors had done any science fiction before, nor would they have much to do with the genre in the future – with the exception of Mario Bava. One possible explanation is that the company’s fortunes had declined, and it tried to emulate the success that low-budget studios in the US and UK had with SF movies.

What seems clear, though, is that someone on the writing team, be it the story originator Virgilio Sabel or screenwriters Marcello Coscia or Sandro Continenza, had some knowledge of literary science fiction. On one hand the script is a hodgepodge of SF movie clichés, many of them lifted from the Technicolor films of George Pal. The build-up to a moon mission was explored in Destination Moon (1950, review), the idea of a large heavenly body colliding with Earth was familiar from When Worlds Collide (1951, review), scenes of the protagonist running through the ruins of a city on fire looking for his woman seem inspired by The War of the Worlds (1953, review), and one of the crew going batshit crazy and ranting about space exploration being an affront to God was a central plot point in Conquest of Space (1955, review).

But there are also subtler borrowings that seem to come straight from literary science fiction, rather than from the movies. The Day the Sky Exploded actually begins with a short – and wholly pointless – segment involving three potential astronauts that are on the shortlist of being the first man around the moon. The actual pilot is not chosen until mere hours before the launch. This is lifted straight from Arthur C. Clarke’s early novel Prelude to Space (1951). The fact that this segment is in the movie without it having any bearing on the plot seems like an indication that someone had actually read Clarke’s novel and liked the idea. The idea of a heavenly body colliding with Earth was made famous through the movie When Worlds Collide – but it was actually a book long before that, and a bestseller, at that, published by Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie in 1933. However, the novel that The Day the Sky Exploded actually resembles the most is Fred Hoyle’s classic The Black Cloud, published in 1957. In the novel Earth is approached by a cosmic cloud that blocks out the sun, and the story primarily follows an international group of scientists trying to save humanity by understanding the cloud – with the help of computers. The dynamic between the scientsts in the film have certain similarities to that of the book. The Russian scientist of the movie, in particular, seems inspired by his literary counterpart. The book also contains a combined effort of several nations trying to deal with the cloud (which is actually a civilisation) with nuclear weapons – however in the book they fail. My guess is that story originator Virgilio Sabel read Hoyle’s book upon its publication in 1957, and decided to try and get a story inspired by it turned into a film in Italy.

Thematically, the film clearly aims at making a comment on the cold war nuclear arms race – even if it is set in some kind of parallel universe where the cold war doesn’t realy seem to exist. The screenwriters envision a future where American and Russian scientists work side by side in achieving common progress for humanity, as opposed to reality, where both blocs frantically competed with each other both for the sake of prestige and for geopolitical reasons. Very much in line with Gojira (1954, review), the movie has a schizophrenic relationship to the nuclear bomb. It is a nuclear-powered rocket that takes man into space, but it is the same nuclear rocket that causes all the problems. And in the end, it is the combined nuclear arsenal of the world – compiled, as the script states, to destroy mankind – that ultimately becomes humanity’s salvation.

The film doesn’t so much resemble the American low-budget science fiction films of the time as the British films of the first half of the 50s. British SF movies in the early 50s were decidedly Earth-bound, often merging the aviation film and the cold war spy drama. In particular, there was a certain strand of science fiction movies beholden to David Lean’s aviation drama The Sound Barrier (1952). Examples of these are The Net (1953, review) and Spaceways (1953, review) – the first dealing with the secret testing of a supersonic aircraft and the second with preparations for the first orbital space flight. Both movies take place on secluded science stations where men and women work hush-hush with dangerous and groundbreaking new technology, and both continuously lose track of their plots by veering off into cold war spy drama and especially soap opera level personal drama – drama which has little bearing on the plot itself. It’s as if the British filmmakers didn’t trust the science fiction elements to carry the movies, but that they needed elements of more traditional drama to appeal to audiences, despite the frequent difficulties of marrying the the disparate elements into a functioning whole.

The Day the Sky Exploded isn’t quite as bad as all that, and keeps the main plot front and centre att all times. But it does fall into the same trap as so many other science fiction movies of the day, thinking you need a romance plot and a domestic drama in order to keep audiences happy. This was ultimately a failing to understand your audiences. Kids who went to see space movies weren’t interested in whether the hero got on with his wife or not, and people who wanted to see domestic drama didn’t go to see low-budget space movies. So these films bored their actual audiences trying to placate a potential audience that wasn’t there. But that said, The Day the Sky Exploded only commits minor sins in this regard. More annoying is the tired “female scientist” trope that was so ever-prevalent in 50s SF movies: the idea that a woman had to “turn off” her “womanhood” in order to be a scientist. The film tries to counteract this trope by having the Leduq be the dick by making a bet over her – but then squanders the goodwill by having Katy fall in love with him anyway.

I have an understanding for the fact that the screenwriters feel the need to pad out the film’s running time with petty personal drama, as there’s little else here to hold on to, apart from the immediate and impending disaster. Because the screenwriters have taken the apocalypse angle but forgotten to fill it with any meaning, they have a hard time filling out the film’s 80 minutes. The afore-mentioned novels that the film takes its inspiration from used the apocalypse theme for ruminations about the nature of humans and society. But instead of using the apocalypse as a tool to tell a story about humanity, The Day the Sky Exploded takes the tool and turns it into the story. This is not in itself a bad thing, if you are intent on making a riveting action film. The only problem here is that pretty much all of the important action takes place between to people pushing buttons on a computer, which never makes for very exciting viewing. McLaren goes up in space and comes down during the film’s first 15 minutes, and after that the screenplay’s only real challenge is to fill 60 minutes of film until the scientists manage to push the launch button on the nuclear missiles.

Now, I don’t want to sound like I hate this film, which is not the case at all. In fact, I found it throroughly enjoyable. I like the fact that, like many European SF movies of the time, it goes beyond the cold war squabbles of the era and envisions a future based on international cooperation (as opposed top US jingoism). I like the fact that there is no Soviet saboteur or ex-Nazi mad scientist. I especially like the fact that the real heroes of the movie are the two mathematicians punching buttons and reading hole cards. Unfortunately, this also means that it is so much more difficult to squeeze drama and action from the movie – it is by no means impossible, and a better screenwriter could have done the job.

That said, the movie is able to conjure up a decent amount of tension and drama from what is there, and Mario Bava’s direction manages to turn up the heat (sometimes literally) in the claustrophobic setting of the science station. Another thing The Day the Sky Exploded has going for it is that it looks a lot better than a film of this calibre has any right to look. Again: credit for this goes to Bava, who acts as director, cinematographer and special effects creator. The photography and lighting is above par for what we expect from a low-budget SF film, with Bava incorporating the long shadows and the beautiful chiaroscuro lighting he would become so famous for in later years. For his effects, Bava relied on low-budget techniques. There are scenes in which strange halos appear in the sky over the world’s cities. For this, Bava simply made large prints of different city skylines and lit them from behind with strong lights. For the final scene in which the missiles are fired against the meteor, Bava got dozens of hobby rockets and filmed several passes of them against a black background in his backyard, making it look like hundreds of missiles in the final cut.

Unfortunately, for much of the action, Bava relies on stock footage, one presumes out of budgetary necessity. There’s numerous shots of animals stampeding, refugees on the run, and at one point Bava has dug up every single shot of rocket launches he has been able to find. The run-up to the finale consists of a full three-minute montage of stock footage of rockets being fired – that’s at least two and a half minutes too long. Because there is so little actual action in the script, which mainly consists of scientists talking, the screenwriters or Bava himself have resorted to padding out the running time with endless cuts to people repeating orders and numbers in microphones all over the world, in an attempt to widen its scope from the small studio in which most of the picture is shot.

I have been unable to find a subtitled version of the Italian print of the movie. A DVD is available, but it doesn’t seem to have English subtitles. However, the 1961 English dub is available online. The fact that it is dubbed actually doesn’t matter all that much, since the original Italian film was also heavily dubbed. The two lead actors, Paul Hubschmid as McLaren and Madeleine Fischer as matemathician Katy Dandridge, were both Swiss actors, and even though they probably spoke Italian on set, they are both dubbed by Italian actors. Jean-Jacques Delbo and Gérard Landry spoke French on set (as this was a French-Italian collaboration) and were also dubbed, as were probably also Annie Berval and S. Louis Casta. There are no documents on the English dub actors, but we do know that Hubschmid was dubbed by Shane Rimmer, who went on to voice Scott Tracy in Thunderbirds (1965-1966).

Overall, Excelsior Pictures’ English dubbing is quite adequate, without major hilarities of faux pas’. All the main characters are dubbed fairly well, with the exception of McLaren’s kid Dennis, who is voiced by an atrocious child actor. Rimmer does John McLaren well, especially considering Paul Hubschmid’s stiff acting. The actor dubbing Russia’s Boetnikov is a standout, capturing the character’s liveliness and warmth, and also doing a fairly convincing Russian accent without going over board with it. Interestingly, Leduc is not voiced with a French accent. The only really atrocious accent in the film is one given to a Japanese radio operator.

Of course, one is always on somewhat shaky ground when reviewing dubbed actors, as voice and physical acting are so closely linked. However, my impression is that the acting in The Day the Sky Exploded ranges from OK to good. Paul Hubschmid – who acted under the name Paul Christian in Hollywood – was never particularly impressive as a leading man, even if he got a number of lead roles. He’s not bad, either, but tends to walk around his hero roles with a sort of expressionless stiffness, as if channeling his best John Wayne. It doesn’t help here that his scenes in the cockpit are played as if he was drugged. This is an odd piece of direction, as if the director thought that one’s ability to move one’s face and emote would somehow be hampered in space. Madeleine Fischer gets the unthankful task of playing the “walking refrigerator” who becomes woman only when she takes off her glasses and lets her hair down – and her character’s failure to engage can’t be blamed on the actress. Jean-Jacques Delbo stands out as the Russian scientist, but he is also helped by his character being both the most colourful and sympathetic in the film. The rest of the cast are largely fine, but don’t make much of an impact.

Carlo Rustichelli’s score does much to add drama to the proceedings. Venanzio Biraschi’s and Oscar De Arcangelis’ soundtrack is also worthy of mention, however it overuses the loud and drawn-out electronic “booooooiiiiiiing” sound supposedly made by the radar to the point that it becomes endlessly irritating.

All in all, The Day the Sky Exploded is a film with a rather equal amount of hits and misses. The story is derivative, but dealt with in an, at least occasionally, intelligent manner. It’s hopeful internationalism is a refreshing respite from the cold war histrionics of the era – as opposed to many similar American films, an apocalyptic event is not necessary to bring the world’s peoples together: they are already together when the film begins. Alas, the script also lacks momentum and treads water for too long, padding out proceedings with soap opera, stock footage and too many scenes of people repeating orders over radios. But thanks to Mario Bava’s stylish direction and surprisingly effective low-cost effects, as well as a few good performances, The Day the Sky Exploded is well worth a watch.

Reception & Legacy

La morte viene dallo spazio was released in Italy in September, 1959, and also saw distribution to a number of European countries. The film flopped at the Italian box office. A dubbed version, as The Day the Sky Exploded, premiered in January, 1961 in the UK and February the same year in the US.

As is usually the case with non-Anglophone pictures from the 50s, I have found few contemporary reviews. However, since the film was released in the UK and US, I have dug up a couple, and both are moderate. British Monthly Film Bulletin noted the heavy use of stock footage in what it deemed “an otherwise routine, tamely directed program picture”. However, the magazine opined that it was of some interest and that the “disparate material has been quite ingeniously assembled”. American Motion Picture Exhibitor said that the film “generates considerable excitement despite a profusion of library stock shots”. The critic continued: “It is satisfactory in all departments, although not of art house calibre”.

Later critics are somewat divided on the merits of The Day the Sky Exploded. Italian Raffaele Meale at Quinlan, perhaps viewing the film through a somewhat patriotic lens, is very positive, giving the movie a 7/10 rating, noting its place in Italian movie history as the first serious science fiction film produced in the nation. On the negative side, Bill Warren in his book Keep Watching the Skies! does commend the “ingenious” use of stock footage, but otherwise feels “the characters are dull, and so is the talky, claustrophobic film”. In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy also has little good to say about the movie: “The picture’s main asset is Bava’s excellent cinematography; both acting and direction fail to transcend a poor script.”

Other reviews are middling. Kim Newman states that “there’s an almost neat idea” in that “the sane scientists have so deeply repressed the fact that their pure research is indebted to the military that only a fanatic remembers this when the Earth actually needs weapons”. However, he notes that the film is “stuck with a lot more scenes of people talking into microphones and poring over consoles than anything as spectacular as, say, the sky exploding as promised in the title”. Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster opines: “For those who love Fifties Science Fiction, this one sits comfortably in the middle, neither terrible nor one of the greats. It is definitely a bit slow, but it is still one of the best looking black and white science fiction films of the era.” Jessica Amanda Salmonson writes under the nome de plume “Paghat the Ratgirl” at Weird, Wild Realms: “The Day the Sky Exploded is plodding but drums up a bit of suspense & believability”.

The film’s biggest legacy is probably the fact that it is directed (uncredited) by Mario Bava, who would go on to almost single-handedly create the giallo genre, and dabbled somewhat in SF. And while it is not Italy’s first science fiction movie, one can argue that it is Italy’s first serious space movie.

Cast & Crew

Paolo Heusch is something of a forgotten director who got in on the wave of Italsploitation horror (and SF) movies in the late 50s, culminating in Mario Bava’s giallo masterpieces in the 60s. He only directed 10 movies and was completely forgotten by the time of his death in 1982 – so much so that in the mid-2010s IMDb didn’t even have a record of his death. And while no-one deserves to be forgotten, it is questionable whether Heusch’s work stands up to being re-evaluated.

Heusch entered the movie business as a script supervisor and continuity controller after WWII, and quickly became a director’s assistant and assistant director in the early 50s. This led to his first directorial credit in 1958 with La morte viene dallo spazio, or The Day the Sky Exploded. I write credit, because the prevailing opinion seems to be that it was Mario Bava who actually directed the movie. It is unclear, however, if Heusch only received the credit, or if he was actually involved in the directing, as co-director, as was often the case with Heusch. By this time Heusch was an experienced and well-regarded assistant director, so it’s probably not that he didn’t have the chops for the job.

Heusch then continued on a 12-year directorial stint, with a rather erratic track record consisting of the post-WWII drama Un uomo facile (1959), the werewolf thriller Lycanthropus (1961, released in the US as Werewolf in a Girls’ Dormitory) and the neorealist drama A Violent Life (1962, based on Pasolini and and co-directed by Brunello Rondi). He then proceeded to co-direct three movies starring aged and by this time blind comedic legend Toto between 1963 and 1966, before further broadening his palette with an adventure movie, a heist movie and a quickie Che Guevara biopic released just months after the revolutionary’s death, and ending his directorial career in 1970 with erotic drama. The films, according to my understanding, were all fairly competent but both routine and flawed, with little in common as to define any particular directorial style or intent. Seemingly, Heusch took whatever chance he was given to direct, regardless of material. The best write-up I can find about Paolo Heusch is by Rafaele Meale at Quinlan. Meale is adamant that Heusch was systematically discriminated and thwarted by the Italian movie business because of his semi-open homosexuality. LGBTQ+ themes have retrospectively been assigned to his movie A Violent Life, and it was featured out of competition under the Queer Lion banner at the 65th Venice Film Festival in 2008.

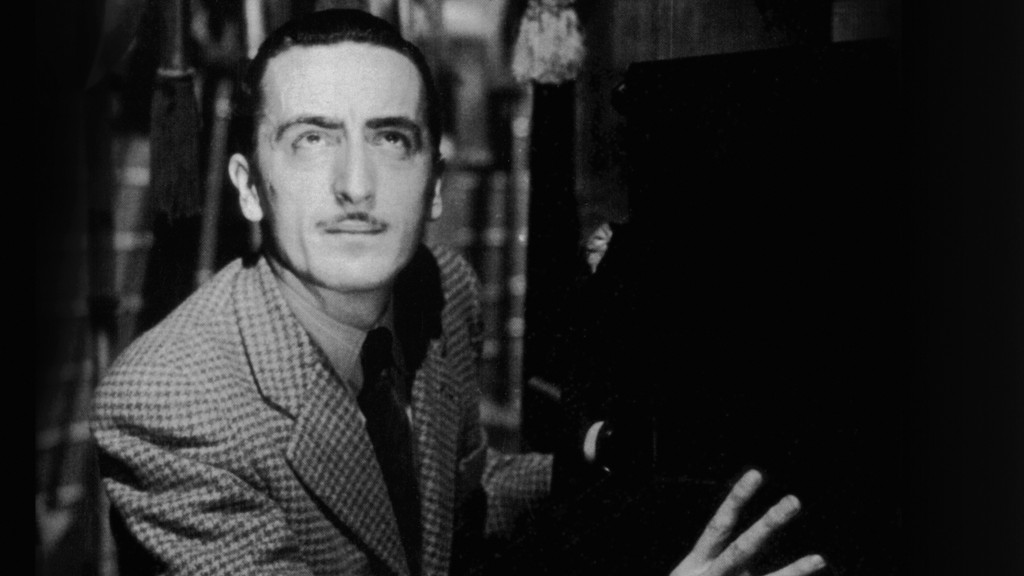

Director/cinematographer Mario Bava is worthy of a lengthier write-up, but that will have to wait until a later post. Suffice to say, Bava is a legend, credited as the father of giallo, and the grandfather of the slasher movie. Originally a cinematographer and special effects creator, he did five uncredited directorial jobs in the late 50s and early 60s before earning his first directorial credit – these five include science fiction and horror movies and two peplum films starring Steve Reeves. The early 60s saw him making a slew of Italsploitation and spaghetti movies – peplums, horror, fantasy, historical adventure, crime and a western, before Blood and Black Lace (1964), often considered his giallo masterpiece. In 1958 he directed the first serious Italian SF movie in sound, The Day the Sky Exploded, in 1959 he made his own blob movie, Caltiki the Immortal Monster, and in 1965 made science fiction history with Planet of the Vampires, seen as a major influence on Alien (1979). His fourth and last SF movie was the comedy Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs (1966). He is particularly remembered for films like Black Sunday (1960), Black Sabbath (1963), Blood and Black Lace (1964), Diabolik (1968) and Bay of Blood (1971). He also worked behind the camera on Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo (1970) and Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980).

Lead actor, Swiss Paul Hubschmid, was born in 1917, and trained acting in Austria under Max Reinhardt, before embarking on a stage career in the 30s. He made his Swiss screen debut in 1938, and had a successful 10-year career on the German language stage and in films in Switzerland, Austria and Germany, often playing leads. However, none of the films he participated in during this period are particularly noteworthy.

Hubschmid got a seven-year contract with Universal in 1948, and made his Hollywood screen debut in a co-lead in the adventure movie Bagdad in 1949, alongside Vincent Price and Maureen O’Hara. For understandable reasons the studio changed his name to Paul Christian. Hubschmid was fluent in English and spoke almost without an accent, but despite this, he got only one role between 1948 and 1952, a lead in the 1950 Italo-US B-movie The Thief of Venice, filmed on location in Italy. In 1952 he started faring slightly better, but spent the next two years playing romantic leads in a handful of B-movies, one of which was the science fiction classic The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), which became a surprise hit. When he realised that his career wasn’t really going anywhere in the US, he dissolved his contract after four years and moved back to Germany.

Hubschmid continued his German stage career, and in 1961 scored the role of Professor Higgins in the German premiere of the musical My Fair Lady. This would be the role that would define his career, and he played it over a thousand times on stage. Alongside his stage work, Hubschmid was busy making movies all over Europe, although few of his films reached an English-speaking audience. Particularly popular in Europe were two adventure films directed and released back-to-back by Fritz Lang, starring Hubschmid as the hero: The Tiger of Eschnapur (1959) and The Indian Tomb (1959). The films were mangled and re-edited into a single 90 minutes long feature called Journey to the Lost City in USA. The year before that he starred in Italy’s first serious science fiction talkie, directed by Mario Bava, The Day the Sky Exploded (1958). Hubschmid appeared alongside Michael Caine, Oskar Homolka and his wife Eva Renzi in the German-British production Funeral in Berlin (1966) and the American WWII movie In Enemy Country (1968). He had the dubious honour of starring alongside Burt Reynolds in the missing link movie Skullduggery in 1970. Hubschmid practically retired in 1975, but still appeared sporadically in film and on TV until 1992. He passed away in 2001, 84 years old.

Madeleine Fischer was another Swiss actor who appeared in The Day the Sky Exploded (1958). Fischer moved with her mother to Rome in the early 50s, and here she became involved in acting, making her debut in the humorous mockumentary Siamo donne (1953), following female movie stars like Ingrid Bergman and Alida Valli playing fictionalised versions of themselves. In 1955 she had a supporting role in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Le amiche, which was followed by a handful of leads and supporting roles in lesser films. Never particularly interested in an acting career, Fischer retired from acting in 1958 and opened a fashion store and became a successful businesswoman. In the 70s she became involved in numerous artistic endeavors. She passed away in 2020.

Fiorella Mari also had a short movie career, stretching from 1953 to 1961. She is best known for her leads in the comedies Are We Men or Corporals (1955) and Fathers and Sons (1957). Sligthly better known is Ivo Garrani, who appeared in over 100 films in five decades. He is most famous for playing the lead in Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (1960). Garrani was a staple in sword-and-sandal films, playing King Pelias in Hercules (1958), had a small role in Hercules and the Captive Women (1961) and appeared as Julius Caesar in The Slave: Son of Spartacus (1962), directed by Sergio Corbucci. He had a bit-part in Luciano Visconti’s historical drama The Leopard (1963) starring Burt Lancaster and a featured role in the action movie Street People (1976) starring Roger Moore. He also appeared in the science fiction movies The Day the Sky Exploded (1958), again directed by Bava, and Atom Age Vampires (1960), as well as the horror films Holocaust 2000 (1977), with Kirk Douglas in one of his more dubious role choices, and Zora the Vampire (2000).

Giacomo Stuart Rossi is probably best known for appearing alongside Vincent Price in The Last Man on Earth (1963), and in Italy’s first science fiction talkie The Day the Sky Exploded (1958). The voice actor dubbing Giacomo Stuart Rossi in The Day the Sky Exploded was Riccardo Cucciolla, by the time an anonymous radio and voice actor. In 1971 he would gain international fame for his role as Nicola Sacco in Sacco e Vanzetti, which earned him a best actor award at the Cannes Film Festival and several Italian awards. He appeared in numerous films of both higher and lesser prestige between the 50s and the 90s.

Janne Wass

La morte viene dallo spazio. 1958, Italy. Directed by Mario Bava & Paolo Heusch. Written by Virgilio Sabel, Marcello Coscia, Sandro Continenza. Starring: Paul Hubschmid, Madeleine Fischer, Fiorella Mari, Ivo Garrani, Dario Michaelis, Jean-Jacques Delbo, Sam Galter. Music: Carlo Rustichelli. Cinematoghraphy & special effects: Mario Bava. Editing: Otello Colangeli. Production design: Beni Montresor. Makeup: Angelo Malantrucco. Produced by Guido Giambartolomei for Lux Film & Royal Film.

Leave a comment