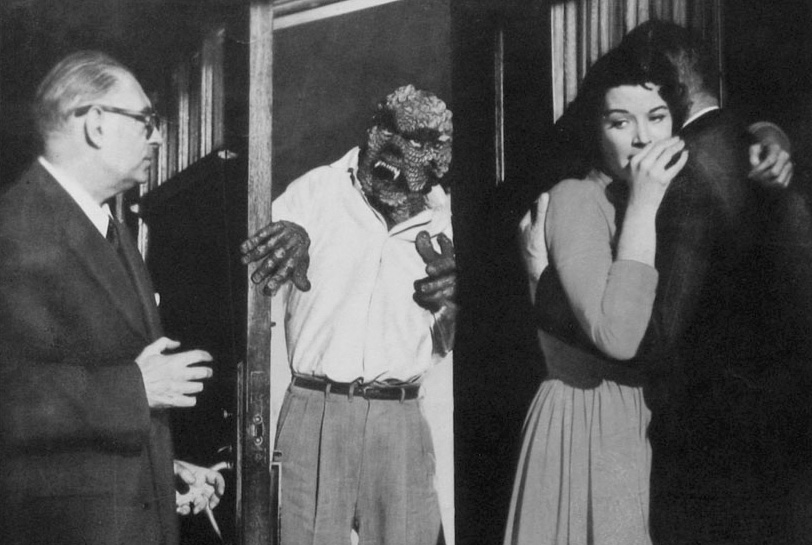

After a radiation accident, producer/director Robert Clarke turns into a lizard man every time he is exposed to sunlight, and into an idiot every time he sees busty Nan Peterson. The two factors in combination spell disaster in this occasionally decent 1958 no-budget effort. 4/10

The Hideous Sun Demon. 1958, USA. Directed by Robert Clarke & Tom Boutross. Written by Clarke, E.S. Seeley, et.al. Starring: Robert Clarke, Nan Peterson, Patricia Manning, Patrick Whyte, Peter Similuk. Produced by Robert Clarke & Robin Kirkman. IMDb: 4.3/10. Letterboxd: 2.7/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

An ambulance departs from a nuclear test lab, and we’re informed its occupant is Dr. Gil McKenna (Robert Clarke), who’s had an accident with an isotope. In the waiting room we meet a worried fiancée/assistant Ann (Patricia Manning) and, apparently, boss, Dr. Buckell (Patrick Whyte). The conversation they are having is meant to inform the viewer that Gil liked to drink. A later conversation between Gil and a nurse is meant to inform the viewer that he also likes to flirt with women. Doctors are baffled that Gil seems to be in almost perfect health despite having suffered a near-fatal dose of radiation, but decide to keep him for observation. We then follow Gil as he is taken to the sun roof, where he dozes off. Cut to an old lady (Pearl Driggs) who asks for help with a magazine – we see her horrified face when she looks at Gil after him being in the sun for a while: “Your face!” she screams. We then follow his pants and shoes as he rushes into his hospital room. Before he smashes his mirror, we see a brief glimpse of a scaly, reptilian face.

So begins The Hideous Sun Demon, a 1958 movie, independently produced, directed and starred by actor Robert Clarke, with help from Tom Boutross. The film is perhaps best known for being the only film directed by Robert Clarke, in an attempt to cash in on the late 50s monster movie craze. At least in some areas, it played as a co-feature to Roger Corman’s Attack of the Puppet People (review).

To Buckell and Ann, Gil’s physician (Robert Garry) explains that the radiation has caused Gil’s cells to undergo a “reverse evolution”, taking his body back to humanity’s reptilian ancestors, and that sunlight triggers the transformation. Therefore, Gil should avoid the sun at all cost. Back home, Gil wallows in self-pity, and it takes some effort for Ann to even convince him to see specialist Dr. Hoffmann (Fred La Porta). However, La Porta arrives and tells Gil that he might be able to cure him, but that it will take some time to work out.

Gil, however, is not good at waiting, and instead hits the local dive bar, where he sees blonde Trudy Osborne (Nan Peterson) sing a moody jazz number called “Strange Pursuit”. Sparks fly, but they are interrupted by the sinister George (Peter Similuk), who is all set to go spend the night with Trudy (whether he is her lover, pimp or customer remains unclear throughout the film). Nevertheless, Gil and Trudy end up on a romantic “stroll” at the beach, where Trudy gets wet and naked, and the two end up falling asleep in each others’ arms. However, as Gil wakes, he realizes the sun is soon about to rise, and he jumps in his car, leaving Trudy half naked alone on the beach.

When Gil shows up at the bar again the next night, Trudy is less than happy, and so is George. At the behest of Trudy, George and his goons go to work on Gil, until Trudy takes pity on him and takes him home to her place. But soon George shows up again, and forces Gil into the sunlight at gunpoint. Gil turns and kills George, and then escapes home. However, the police soon arrive, and George flees in panic, and runs over a police officer in his car. He then drives out to an oil field, where he takes refuge in a shack. Here he befriends a little girl, Suzy (Xandra Conkling), who takes pity on him and goes home to get him cookies. However, her mother catches her, and makes her confess that they are for a man hiding in the shack. The mother, having heard the news bulletins of a murderer/monster on the loose, calls the police. The police chase Gil, now in reptile form, up onto a tall gas holder, where he is eventually shot dead, and plunges to the ground, King Kong style.

Background & Analysis

When we think of 1950s science fiction movies, our minds usually go pictures like Destination Moon, The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Thing from Another World, Invasion from Mars and The War of the Worlds. One might say they represent the best of what 50s science fiction had to offer in the decade. Another thing they have in common is that they were all made in the early 50s. While this era is a Golden Age of SF movies, the fact is that not that many SF films were made then. My list of science fiction movies from the year 1950 on this website has 6 films. I have reviewed 15 films from 1951 and 13 from 1952. By comparison, I have reviewed over 40 films from 1957, and I’m still in the midst of reviewing movies from 1958, and I’ve already gone through 32 of them, this one being number 33. If the early 50s was a Golden Age in terms of quality, then the late 50s was a Golden Age in terms of quantity. Despite the astounding number of SF movies being churned out of Hollywood in the era, few can be considered really good. In the second half of the 50s, there are really only, arguably, three movies that can be considered bona fide classics in terms of quality: Forbidden Planet, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Incredible Shrinking Man, and these were all made in 1956 and 1957.

No major studio made an effort to create high-quality science fiction movies past 1956. The genre was not seen as bankable and not worth lavishing budgets on. However, there was one studio that proved that science fiction could have commercial value. American International Studios (AIP) emerged in the mid-50s as a small, low-budget outfit geared toward the juvenile and teen market, and was very much an embodiment of the spirit of their most famous producer and director, Roger Corman. Corman was aghast at how much major studios spent on their movies when, in his mind, all you really needed was a camera, a director and a few actors. AIP and Corman quickly realised that that if you kept the budget sufficiantly low, you could almost be guaranteed a profit as long as you sold your film well. Films dealing with juvenile delinquency, promiscuous women, fast cars, monsters and science fiction were favourites among the young crowd. And AIP’s studio executives James Nicholson and Sam Arkoff noted that if they kept their costs at under $100,000, put a monster and/or a scantily clad girl on a poster, came up with a juicy title and had a scintillating tagline, they were almost guaranteed a profit. With shooting schedules often lasting no more than a week, AIP could spit out several films a month, making a small profit on most of them — accumulating, in the end, a rather large profit. And around 1957, other studios also started catching the drift, leading to a deluge of badly scripted, quickly filmed and cheaply produced science fiction and monster movies and teenage movies, in an ever-growing degree aimed at the drive-in market.

The Hideous Sun Demon was the brainchild of producer/director/actor Robert Clarke. Clarke was a working actor stuck in B-movies and TV guest spots, who had an epiphany after appearing in the AIP-distributed science fiction monster movie The Astounding She-Monster (1957, review). Even though the movie was made with pocket lint ($18,000) and incredibly bad, it made a killing at the box office, largely thanks to its poster. Clarke had lowered his acting fee for four percent of the profits, which turned out to be a good investment. He realised that he could make a lot more money producing a bad monster movie than trying to act in serious movies, and decided to write, produce, direct and star in a science fiction monster movie of his own.

The first draft (titled “Sauros”), written by Clarke and co-director Tom Boutross, and possibly Clarke’s friend, actor Phil Hiner, had a very different plot. This version focused on uranium prospectors in Guatemala, stalked by a man who turns into a reptilian when exposed to the sun, due to radiation experiments conducted by his father. The finished story, possibly because of budgetary reasons, became something very different, although the idea of a man being turned into a reptile when exposed to the sun remained.

This idea probably stemmed from the recent discovery in 1956 that long exposure to sunlight caused mutations in skin cells, leading to skin cancer. This was such a talking point in the era, that an opening narration only has to mention “newspaper headlines [about] a radiation hazard from the sun far more deadly than cosmic rays” for the audience to be keyed in. However, the narration also implies that this discovery came from information gathered by the satellites Explorer 1 and Explorer 3, which is complete bogus. It was Australian scientist Henry Lancaster who discovered the link between melanoma and the intensity of sunlight.

The main frame of the film is a riff on the Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde trope, or even more so, on the Hollywood werewolf trope. But instead of a full moon acting as the agent of transformation, here it is sunlight that that is the bane of our protagonist (in a sense, also drawing inspiration from Dracula and other vampire stories). As such it is not a bad idea, even if it is rather derivative. But it puts enough of a spin on a tried and tested formula that it should have been possible to write an interesting story around it. It is also to Clarke’s credit that he makes Gil a flawed protagonist without pushing him over the edge into villainy. The usual spin on werewolf films was often to have a wholly wholesome character swept up in a tragedy because of a curse or an accident, as outlined by Lon Chaney, Jr.’s Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man (1941). Or to have a man fall victim to his own hubris, as in the many Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde adaptations. In the case of Gil, it is an accident that sets off the tragedy, but it is Gil himself that digs himself ever deeper into his hole through his self-pity and his inability follow the simplest of instructions: don’t leave the house until Dr. Hoffman has cured you. Instead of waiting the few weeks it would take to put things right, Gil hits the local bar and goes out on nightly excursions that he knows he should not partake in. He is not really a tragic figure, he is pathetic. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Clarke says that it was his own idea to create a character that defied the usual protagonist mold.

The Hideous Sun Demon really was a product of Clarke taking a screenwriting class at the University of Southern California, he tells Weaver in the interview. Inspired by the success of The Astounding She-Monster, he told his fellow students that he wanted to produce a feature film, and most of the crew, as well as part of the cast, were drawn from the student pool at the university’s cinema department. The screenplay was written by a student called E.S. Seeley, Jr., and polished, mainly in regards to the dialogue, by the more seasoned writer Donald Hoag. Fellow students Tom Boutross took on directing duties, Robin Kirkman became associate producer and Latvian immigrant Vilis Lapenieks became the main cinematographer. Shooting took place over twelve weekends, which was when the crew was able to get away from their studies. The original budget was supposed to be $10,000, but ballooned into $50,000.

Robert Clarke was the sole marquee name for The Hideous Sun Demon. The only other person, really, with any film acting career to speak of in the cast is Nan Peterson, who plays the sultry bar singer, although this was her first movie role. She later went on to star in a couple of other low-budget movies and TV. At the time, she made her living as a model, but she did have some experience from acting on stage and in local TV, as well as some TV directing. The Hideous Sun Demon was likewise the feature debut for Patricia Manning, who went on to do a few bit parts in film and a dozen TV appearances. The film provided Patrick Whyte with what must have been the most prominent movie role in his career as Dr. Buckell – Whyte was one of the few seasoned professionals on the film, although he was usually assigned to bit-parts. Most other actors in the movie were made up of Robert Clarke’s friends and relatives and actor hopefuls that his university buddies knew.

The most prominent of these was Donna King – of the famous singing King Sisters – she was sister-in-law to Robert Clarke. King plays little Suzy’s mother, in a case of fiction meeting reality. Suzy was played by Xandra Conklin, Donna King’s real-life daughter. The elderly woman who first discovers Gil’s transformation on the hospital roof was played by Pearl Driggs, Donna’s mother. Donna’s sister Marilyn King also wrote the jazz number “Strange Pursuit” which is sung several times in the movie by Trudy. In actuality, it is Marilyn King’s voice we hear and not Nan Peterson’s.

Considering The Hideous Sun Demon is basically a student film directed and produced by people with no experience in directing and producing and with most of the cast filled with amateurs, it is actually surprisingly competent. While the direction is often plodding, the movie has moments of inspiration, a number of quite dramatic camera angles and makes good use of wide shots on location, for dramatic effect. The film had three different cinematographers, of which one, the best according to Clarke, was Vilis Lapenieks, who went on to have a fairly successful career in both films and TV before his untimely death in 1987. The production design is nonexistant, and the movie seems to be filmed almost entirely in existing houses and locations, sometimes with threadbare furnishings. But the locations are used better than in many “professional” B-movies. The low budget is obvious, but not so much in the form of bad production, rather in the abscence of production. As stated, there are almost no sets or even props in the film that have been designed – it is all shot on existing locations, with existing paraphernalia, giving it one the one hand an almost documentary feel, but also a feeling of threadbareness.

That the monster itself looks as good as it does is quite astounding. Clarke first brought his idea to special makeup pro Jack Kevan, who said he could do the lizard suit for $2,000. For what was planned as a $10,000 film, this was obviously too steep a price. In the Weaver interview, Clarke says that he was happy to find a “really happy Italian guy” called Richard Cassarino, who was a film buff, sometime actor and an artist, who agreed to make the suit for $500. The mask was made the traditional way, on a plaster cast of Clarke’s face, and the torso and arms were constructed on a wet suit. This caused problems for Clarke, who did all the creature work, including stunts, himself. It got profusely hot inside the wet suit in the California summer sun, and at the end of takes, he would have been sweating so much that it looked like he had peed in his pants.

Clarke directed most of the movie but he brought in Tom Boutross, who was primarily an editor, to function as assistant director anytime Clarke himself was in monster costume – an awkward suit to direct in. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Nan Peterson heaps praise on Clarke, saying his was “excellent, very nice to work with”.

The acting in the movie is nothing to write home about. Robert Clarke was a sympathetic and capable actor, and comes out with clean papers from The Hideous Sun Demon. Unfortunately, he’s just about the only actor in the movie that can be said about. Nan Peterson was hired mainly because of her figure, says Clarke, and it shows. There’s nothing particularly wrong with Patricia Manning, but she just doesn’t get all that much to do. Patrick Whyte is OK for his stereotypical role, and Peter Similuk as the goon does his best gangster imitation without impressing.

The main problem with the film is the script, as was so often the case in these kind of movies. It stumbles from the very beginning on its ridiculous concept. The idea of a human going through reverse evolution, of course, was a well-worn trope in the late 50s, and had been utilised ape man, werewolf and Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde film for decades. We sort of go along with it in ape man and wolf man films, because these are such iconic tropes, but the idea of man devolving into a reptile because of sunlight is just too much of a stretch of the suspension of disbelief. The film also gives us very little reason to invest in the character, since he brings all his trouble on himself. This is the kind of movie where the viewer screams at the screen because of all the stupid decisions made by people in it. On one hand, Gil really only has himself to blame. All he has to do to avoid becoming a lizard man is to stay at home and avoid sunlight. Instead he goes out to booze, cheat on his girfriend and falls asleep on a beach, after he has angered a mobster by robbing him of his date. Furthermore, the incompetence of the medical community and authorities is baffling. While The Amazing Colossal Man (1957, review) had its flaws, at least Bert I. Gordon got one thing right: What do you do with a man who suddenly mutates into a monster in ways that baffle science because of a radiation accident? You put him at a remote, secret research station and place him under constant surveillance. You don’t send him home with a get well note and cross your fingers that he doesn’t go out in the sunlight.

But perhaps the main flaw with the script is that it doesn’t mean anything. It tries to be a tragedy in the way of The Wolf Man – an innocent man struck by disaster, being killed in the end by his own father, after spending the film trying to avoid his family’s curse. But as stated, The Hideous Sun Demon squanders any sympathy we have for Gil by making him solely responsible for his own problems. There’s no morality play here, no sense of a man struggling to overcome his demons, no spin on the fear of the Other, not even a good old red scare parable. Gil has no mission, no villain to destroy, no murdered wife to avenge, no life’s work that has been robbed from him. It’s just a story of a man accidentally being turned into a lizard, who gets killed by a police officer in the end. The ending, as the film, is utterly pointless.

Despite its pointlessness and its budgetary constrictions, The Hideous Sun Demon doesn’t belong among the worst movies of the decade, and is in fact thoroughly watchable if you are into 50s low-budget monster movies. In many ways it overcomes its low budget and fragmented shooting schedule, and looks better than it has any right to do. Despite dips in energy it moves along at an at least acceptable pace, and manages to build up at least some excitement. Occasionally it is quite well filmed, clearly made by a hungry, young crew eager to make something good, rather than slumming actors, money-hungry executives and a director hired in to get 60 minutes in the can, damned be the quality. There’s some amount of passion behind the movie, which makes it more interesting to watch than many films of its ilk.

Reception & Legacy

The Hideous Sun Demon premiered on August, 1958 in Texas, but doesn’t seem to have been playing regularly in theatres until 1960. In some places it played as The Sun Demon. It was released in the UK in 1961 and in Mexico and Japan in 1962. In Britain it was bizarrely retitled Blood on His Lips. Distributor Pacific International Enterprises folded just 18 months after the premiere, taking all of Clarke’s profits with it.

The film doesn’t seem to have been reviewed at all in the US trade press. Upon its UK release, Monthly Film Bulletin gave it its lowest rating and said it had “an air of shabby economy, and rarely excites or entertains”. The magazine continued: “Wordy dialogue, poor acting, uneven photography and sub-standard sound all add to the disadvantage of a hopelessly illogical plot”.

Phil Hardy’s only comment on the film in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies is “The direction here is rudimentary”. Bill Warren in Keep Watching the Skies! calls it “depressing on many levels”.

The movie has a half-decent 4.3/10 rating on IMDb and a 2.7/5 rating on Letterboxd, which it does not deserve.

Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV Reviews says: “It’s the script that’s most at fault here. It’s wordy in the extreme and no-one involved in writing it has any idea what evolution is or how it works. A love story between McKenna and bar pianist Trudy Osborne is never convincing and often feels just bolted on to bring the running time up to speed. The idea is a fairly sound if a sometimes derivative one (in a sense it’s a film about a reverse werewolf) but the story is often related in tedious infodumps. It’s all very dull really.”

Richard Scheib in his 2/5 star review at Moria gives the film some credit: “The Hideous Sun Demon is usually spoken of in dismissive terms but is a film that has some undeniable promise, even if never fully transcending the B-budget ghetto. The makeup on the transformed Clarke looks effective and for once does not belie the ‘hideous’ promise of the title.”

In an interview in Entertainment Weekly from 1997, actor Tom Selleck admitted that The Hideous Sun Demon was one of his “guilty pleasures”.

The movie has been redubbed and released as a spoof with Robert Clarke’s son Cameron in the cast. Bill Warren cites two different spoofs, one with the title The Hideous Sun Demon: The Special Edition and one with the title What’s Up, Hideous Sun Demon. However, …Special Edition does not exist. I have found a press image with both Robert and Cameron Clarke on a set with Cameron in a lab coat. The caption says that the image is taken during the production of The Hideous Sun Demon: The Special Edition. However, IMDb also lists Cameron among the cast of What’s Up, Hideous Sun Demon?, as a scientist.

Warren is tripped up by the fact that his information about …Special Edition is retrieved from an article in Cinefantastique, written before the film had come out, which lists Hadi Sadem and Greg Brown as producers. However Warren claims that they are not listed in the credits of What’s Up, Hideous Sun Demon?, which has Jeffrey Montgomery as producer. This has led Warren to believe that there are two different dubbing spoofs, and that information has then bled into Wikipedia, and from there onto numerous other books, blogs and sites. However, the press image I have found for …Special Edition actually lists all three: Sadem, Brown AND Montgomery as producers, and also states that …Special Edition would be directed by Craig Mitchell … who directed What’s Up, Hideous Sun Demon?. So this simply seems to have been a case of a film changing titles between production and release. What’s Up, Hideous Sun Demon? starts with five minutes of new footage of a group of frat boys sitting down to watch The Hideous Sun Demon. However, the TV screen shows a scientist working with radiation in a lab, a scene not present in the original movie. The scientist drinks some radioactive fluid from a beaker, and then crawls out from the TV screen and spews green goo all over the frat boys – then the movie proper begins. The scientist is supposed to be Gil McKenna, and he is played by Cameron Clarke, reprising his father’s character. However, in the actual film, Robert Clarke is dubbed by a young and unknown Jay Leno. The spoof was made with the blessing of Robert, as evidenced by the press image and his son’s involvement. It was later re-released as Revenge of the Sun Demon.

The confusion regarding this spoof is further enhanced by the fact that the film’s DVD cover lists Sadem, Brown and Montgomery as producers while IMDb lists none of these, only Kevin Kelly Brown as associate producer .

If someone wants to edit the Wikipedia page of The Hideous Sun Demon with this information, I would appreciate it. I already got blocked once for correcting a mistake using my own research as the source.

Cast & Crew

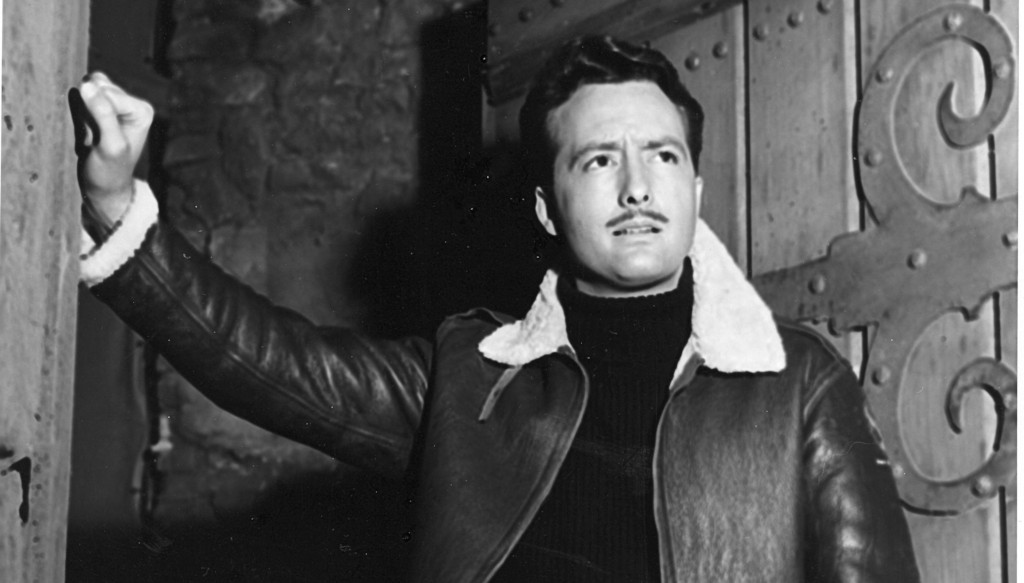

Robert Clarke came up through the ranks from school plays to radio and then Hollywood, where he gut stuck in the B or even Z movie quagmire before embarking on a rather successful career as a TV show guest star in the late fifties through to the late eighties, and even put in a few film cameos during the nineties and the naughties. He passed away in 2005.

Despite having appeared in close to 150 films and TV shows, Clarke is best known as the hero of a number of schlock science fiction films. This included classic The Man From Planet X (1951, review) and the flawed but interesting post-apocalyptic Captive Women (1952, review). He was the hero again in The Astounding She-Monster (1957/1958, review), The Incredible Petrified World (1957), opposite John Carradine, The Hideous Sun Demon (1958), which he produced and directed, Beyond the Time Barrier (1960), directed by Edgar Ulmer and produced by Clarke, Frankenstein Island (1981), again with Carradine, and the sci-fi comedy Midnight Movie Massacre (1988). He also appeared as the narrator in Byron Haskin’s Jules Verne adaptation From the Earth to the Moon (1958, review), in Where’s Willie, Alienator (1990), and The Naked Monster (2005), his last production. Clarke guested a number of sci-fi TV shows as well, including an episode of Knight Rider (1984). Clarke is not to be confused with Robert Clark, director of The Whispering Shadow (1933, review).

Tom Boutross, the co-director and editor of The Hideous Sun Demon (1958), as mentioned, studied cinematography in Los Angeles, and got his first screen credit with the afore-mentioned film while still in film school. After graduating he found steady work at the Walt Disney Company, primarily as an editor on the show Disneyland. From the mid-60s onward he worked freelance, again primarily as an editor, for TV and B-movies, and in the 70s struck up a companionship with cult movie producers and directors Charles Pierce and Earl Smith, and edited, among others, the (in)famous Bigfoot mockumentary The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972), as well as a number of westerns and adventure films. He also worked occasionally as as a producer, TV director and production manager. His last IMDb credit is from 1988, and he passed away ten years later.

Latvian-born Vilis Lapenieks came out of the same student pool as Boutross, and The Hideous Sun Demon was also his movie debut. He then embarked on an eclectic – to say the least – career in cinematography, immediately finding a place in the low-budget indie circles containing such cult filmmakers as Ed Wood, Roger Corman, Curtis Harrington and Arch Hall (both of them). He was the cinematographer on such movies as the Wood-scripted western Revenge of the Virgins (1959), Corman’s The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), the Halls’ nudie cutie Magic Spectales (1961) and Z-movie classic Eegah (1962), Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide (1961, starring Dennis Hopper), Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965) (the the new footage with Basil Rathbone and Faith Domergue, intercut with the Russian original) and Queen of Blood (1965) (the bits that were not pilfered from two Russian films), the bizarre exploitation/education film V.D. (1961), educating the drive-in crowd about the clamp, as well as a number of odd little films dealing with mental illness, the medical properties of LSD, documentaries about the hippie counterculture and civil right struggles, as well as somewhat noteable pictures like Vic Morrow’s prison drama Deathwatch (1965), about gay love in prison, starring Leonard Nimoy, the Oscar-winning insect documentary The Hellstrom Chronicles (1971) and the gangster biopic Capone (1975). And then he filmed the infamously unfunny science fiction spoof The Creature Wasn’t Nice (1981), one of the low-points in Leslie Nielsen’s career. This would be his last movie.

While neither IMDb, Wikipedia or any other film resource I can find mention it, US immigration and geneology websites confirm that Vilis Martins Lapenieks was the son of Latvian film and stage director Vilis Janis Lapenieks. Lapenieks, Sr. is best known for his 1940 film The Fisherman’s Son, in which the director’s 8-year old son actually has a cameo. The Lapenieks moved to the US in 1952, where the father established a photo studio and seems to have worked in some capacity behind the scenes in Hollywood. His son, apparently decides to continue in his footsteps.

Apart from Robert Clarke, there’s not any actors in The Hideous Sun Demon with what you’d call substantial careers. Nan Peterson and Patricia Manning both worked in the movie business for about ten years. Peterson did have a background with work as a presenter and even director at a local TV station, and had done some stage work, as well as worked in journalism. However, when she was cast in The Hideous Sun Demon she was mainly working as a model, and living in the legendary Studio Club, a dormitory for young women in Hollywood. Both Peterson and Manning ended up appearing in around 20 films and TV shows from the late 50s to the early 60s, mostly in uncredited bit-parts or TV guest spots. Peterson is slightly better known thanks to her leads in the super-low-budget films The Hideous Sun Demon, Lee Sholem’s The Louisiana Hussy (1959) and Boris Petroff’s Shotgun Wedding (1963).

EDIT 24.1.2025: Corrected the actor in “Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet” from John Carradine to Basil Rathbone.

Janne Wass

The Hideous Sun Demon. 1958, USA. Directed by Robert Clarke and Tom Boutross. Written by Clarke, Phil Hiner, E.S. Seeley, Jr., Doane Hoag. Starring: Robert Clarke, Nan Peterson, Patricia Manning, Patrick Whyte, Peter Similuk, Fred La Porta, William White, Donna King, Xandra Conkling. Music: stock. Cinematography: Vilis Lapenieks, Stan Follis, John Arthur Morrill. Editing: Boutross. Art direction & monster design: Richard Cassarino. Produced by Robert Clarke & Robin Kirkman for Clarke-King Productions.

Leave a comment