Two rival arms manufacturers strike an uneasy truce to create a rocket to the moon. Byron Haskin’s ill-fated would-be epic never quite gets off the ground, tied down by a talky, slow-moving script and woefully badly written characters whose motivations never become clear. 3/10

From the Earth to the Moon. 1958, USA. Directed by Byron Haskin. Written by Robert Blees & James Leicester. Based on novels by Jules Verne. Starring: Joseph Cotten, George Sanders, Debra Paget, Don Dubbins. Produced by Benedict Bogeaus. IMDb: 5.1/10. Letterboxd: 3/5. Metacritic: N/A.

The year is 1868. Unionist arms manufacturer and inventor Victor Barbicane (Joseph Cotten) has invented a new explosive called Power X, which is so powerful that it cannot be tested on Earth. Gathering the International Armaments Club, he propopses to build a rocket to the moon, where the explosive can be safely tested. The cost will be so incredible, that Barbicane needs financiers from all over the world, and in return, he promises the secret to Power X to all who invest. However, word reaches confederate steel manufacturer Stuyvesant Nicholl (George Sanders), Barbicane’s arch rival. Nicholl is a god-fearing man, who fears that Barbicane’s invention will lead to the destruction of the Earth. To prevent this from happening, he challenges Barbicane to a duel.

So begins From the Earth to the Moon, Byron Haskin’s 1958 Technicolor spectacle, one of the last films produced by RKO, as a part of a Jules Verne fad in Hollywood in the late 50s and early 60s. Apart from the central idea of firing a rocket around the moon, and some character dynamics, little is retained from Verne’s original novels.

Barbicane rejects the duel and goes ahead with his rocket build. However, Nicholl proposes a bet, setting his new unbreakable metal against Barbicane’s explosive. Barbicane accepts, and blows the metal to smithereens, along with an entire mountain. Nicholl is defeated, and Barbicane’s project proceeds. That is, until Barbicane is approached by US president Grant (Morris Ankrum), who orders him to stop the development of Power X and bury its secret, warning that several nations have intended to declare war against USA if Barbicane proceeds. Adding insult to injury, Grant asks Barbicane to, in the interest of patriotism, never reveal their discussion or the reason for him abandoning the project, even if Grant knows Barbicane will be ripped to pieces by his investors. Patriotically, Barbicane agrees.

However, after a few weeks of sulking, Barbicane springs into action anew, and to the surprise of everyone, including Stuyvesant Nicholl’s beautiful daughter Virginia (Debra Paget), Barbicane seeks out Nicholl and asks him to join him on a trip to the moon. The reason: Nicholl’s super-metal is in fact the only thing that will keep Barbicane’s rocket from burning up during re-entry to Earth. After some feigned hesitancy, Nicholl is on board. Cue building and research montages, and a budding romance between Virginia and the rocket’s third passenger, engineer Ben (Don Dubbins). And soon the day of the take-off comes.

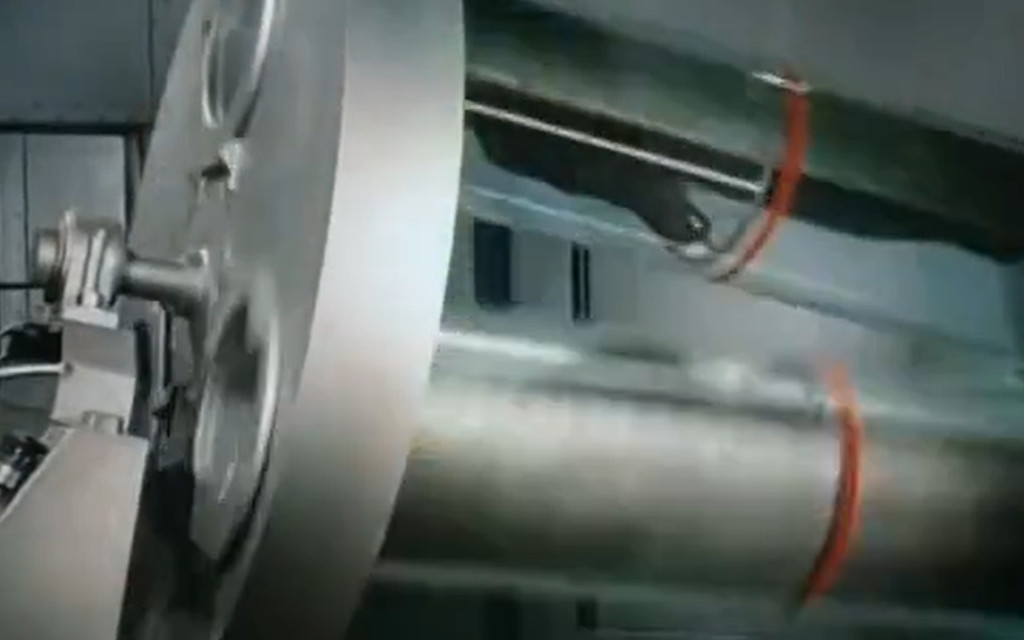

To make a long and somewhat convoluted story short: Nicholl believes it is God’s will that the evil Barbicane shall die, so he has sabotaged the rocket to malfunction before they can land on the moon. But to his terror, Virginia has snuck onto the ship. Ensues dramatic repairs of the ship’s nuclear(?) reactor, gyroscope and thrusters, long-winded speeches and a belated reconcilement between Barbicane and Nicholl, as Barbicane explains his intent has always been to sell the formula for Power X to anyone willing to pay, thus creating a terror balance that will bring peace to the world. By then, however, it is too late to repair the ship, and the crew are stuck in helpless orbit around the moon, with a nuclear reactor threatening to explode. But by splitting the rocket, Barbicane and Nicholl sacrifice themselves, landing on a one-way trip to the moon, while the two young lovers are set drifting home toward Earth.

Background & Analysis

The success of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954, review) and United Artists’ Around the World in Eighty Days (1956) set off a Jules Verne fad in Hollywood, of which the first offspring was From the Earth to the Moon (1958). The movie was the brainchild of Benedict Bogeaus, a businessman-turned-film producer, who in the early 50s had signed a contract with RKO, producing films for the studio on an independent basis. Bogeaus mostly turned in low- to mid-budget films for RKO, and From the Earth to the Moon was the last picture he made for the company, as the studio folded just before filming began. This led the film to be released by Warner Brothers.

As director, Bogeaus chose Byron Haskin, a veteran of adventure and science fiction films in colour, who had done the George Pal movies The War of the Worlds (1953, review), The Naked Jungle (1954) and Conquest of Space (1955, review). The task of turning Verne’s book into a film script went to Robert Blees, a hack writer for hire, and James Leicester, primarily an editor.

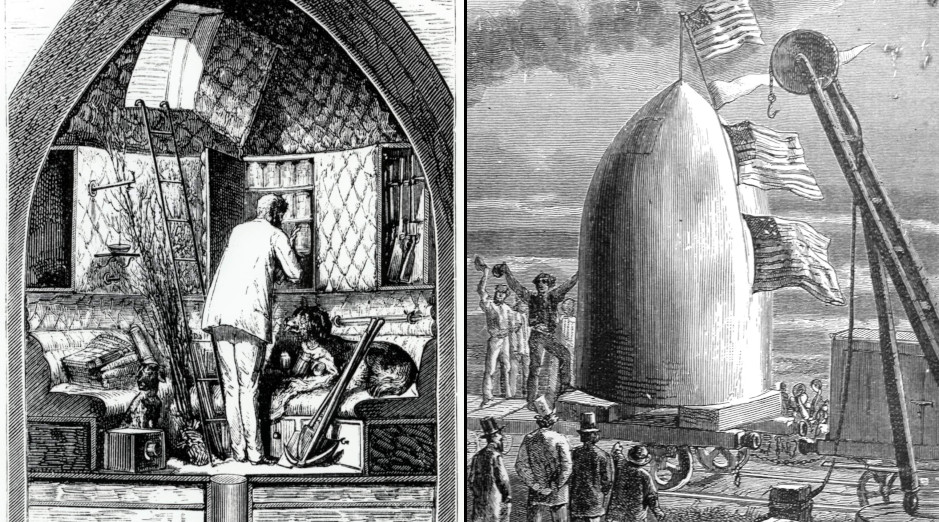

The first hurdle for anyone trying to adapt Jules Verne’s 1865 novel De la Terre à la Lune and its 1870 sequel Autour de la Lune (Around the Moon) is the fact that they are more or less unadaptable as such – in particular the first book. The first book deals to a large extent with the planning of the moon mission, and a surprising number of pages deal with the financing of the project – including long lists of how much and what different countries are contributing, and why they choose to do so. What is retained from the novel in the film is Nicholl’s opposition to the project, which in the book seems to be more out of spite than out of any ideological motivation. The first book ends with Barbicane, Nicholl and a French adventurer, Michael Ardan, setting out together on the voyage. The book, as per usual Verne, contains no romantic interest. The sequel, Around the Moon, follows the lunar rocket approaching and ultimately orbiting the moon, before falling back toward Earth. Along the way, the crew deal with a number of mishaps, such as depositing of a dead dog out of a window, suffering intoxication by gasses, struggling with navigation and almost being hit by an asteroid. In the novel, all three passengers make it safely back to Earth. The first book is Verne’s speculations about the science, cost and building behind a possible lunar mission, and the second is more or less a popularisation of the known astronomy and physics of space in the form of an adventure story, and both books are filled with long-winded technical jargon – perhaps more than in any other Verne novel.

In adapting the material, Robert Blees and James Leicester have applied to the story an anachronistic theme commenting on the nuclear arms race of the 50s, and even the idea of terror balance, a notion that had no application in the 1860s. 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was the first film to update Jules Verne to the nuclear age, again 100 years anachronistically, and that would become the trend for many of the Verne adaptations produced in the 50s and 60s. In From the Earth to the Moon, Power X is a thinly veiled substitute for nuclear power and the nuclear bomb. Barbicane becomes the mouthpiece for nuclear armament and the terror balance – the idea that if all major powers are in possession of nuclear weapons, it will serve as a deterrent to use it, and in a utopian pipe dream, a deterrent to all kinds of wars. Nicholl thus becomes the mouthpiece for the opposition to nuclear proliferation.

One problem with the movie is that it makes Barbicane’s motives highly ambiguous. In the beginning it seems to make it clear that Barbicane looks upon the matter through the eyes of the businessman, and that his aim with Power X is simply to make money, without any moral scruples. It is only in the end that he raises the idea of the terror balance, suddenly speaking as a pacifist, a side that he has previously shown no indication of, leaving the viewer with a feeling of inconsistency – as if the screenwriters are flip-flopping Barbicane’s motives and ideologies to suit the needs of the plot. This flip-flopping is made worse due to the fact that it is likewise difficult to pin down exactly what Nicholl’s motives are. On one hand, Nicholl seems to be driven by a desire for revenge against Barbicane. Nicholl and Barbicane apparently stood on different sides in the American civil war, and it is hinted that it was Barbicane’s explosives pitted against Nicholl’s metals that tipped the war in favour of the unionists, and ruined Nicholl in the process. At the same time, Nicholl accuses Barbicane of being evil incarnated and in league with the devil (his motivations for this remain somewhat unclear), and he looks upon himself as the instrument of God in his intent at killing Barbicane and laying waste to his Power X project. This muddling is made worse by the story having Nicholl seemingly burying the hatchet and engaging with enthusiasm in the moon rocket project, only to reveal that it has all been a ruse from the beginning, and his plan has been to sabotage the rocket all along. That both Barbicane’s and Nicholl’s motivations are unclear throughout the movie and seem to change according to the whims of the plot makes From the Earth to the Moon an excruciatingly confusing movie to watch.

If Barbicane and Nicholl are muddled characters, then at least they are gifted with any sort of personality, which unfortunately can’t be said about any other characters in the movie. Ben and Virginia both feel shoehorned into the picture in order to give it a romance angle. Neither of them have any sort of personality nor any bearing on the plot. They can be completely edited out of the film without the need to change anything. A peculiar choice by the screenwriters is to have the character of Barbicane’s butler be called “JV”. This character is present throughout much of the proceedings, and in the movie’s final moments we learn that he is in fact Jules Verne himself – a revelation that doesn’t have any bearing on the plot, and is completely illocigal. Why would French author Jules Verne be working as the butler for America’s foremost arms manufacturer? Other characters in the film are simply there for plot convenience and exposition.

In one regard the film manages to emulate the original novel: it is slow-moving and talky. The first hour of the film progresses in a staccato episodic manner filled with nonsensical pseudo-scientific explanations and back-and-forth arguments between Barbicane and Nicholl, with little forward momentum. The intervention of president Grant and the order not to divulge the secrets of Power X to the world don’t serve any clear plot purposes and simply feels like the film going around in circles. The main aim of the story is to get Barbicane & Co into a rocket for the moon, and all the back-and-forth around his business ventures don’t affect this in the slightest. It doesn’t get any better once we’re off in space. Barbicane and Nicholl continue to argue, there’s an asteroid passing with no consequence, and then there is a lot of drama around Nicholl’s sabotage and a lot of running around the enormous gyroscope housed in one of the spacious rooms of the rocket. However, despite the tense hopping around electrical arcs, the pulling of levers and dragging of cables, all the science in these sequences is so hopelessly muddled and unclear that it’s difficult to get a crasp of exactly what is going on. Especially since all this drama amounts to nothing in the end, as all the efforts to repair the rocket fail, giving the audience a feeling of having wasted much time on nothing. And all of this could have been avoided if Barbicane had simply told Nicholl of his plans to create a power balance in the first place. When Nicholl, not without cause, asks Barbicane: “Why didn’t you tell me?”, Barbicane answers: “Because you didn’t ask!” Well, that’s one way to justify bad scriptwriting.

Instead of making a riveting story about the first mission to the moon, Haskin and Bogeaus have made a slow, confusing parable about the nuclear arms race that seems to be unsure about what it is actually trying to say, seemingly advocating for both non-proliferation and proliferation at the same time.

According to an interview with Debra Paget, the stilted awkwardness of the script may not simply be the screenwriters’ fault, as she says lead actors Joseph Cotten and George Sanders rewrote much of the script themselves, adding to their own material and cutting away lines from other actors. Paget says she personally didn’t mind it, as her character was non-essential in the first place.

Filming took place in Mexico, most likely as a cost-cutting measure. According to some sources, it was originally intended to have a much larger budget, and would have included scenes from the moon. In the finished product, we see almost nothing of the rocket travelling through space, and the final moon landing – surely a highlight of any moon voyage film – happens off screen and is relayed almost as an afterthought. The sets of the rocket interior probably swallowed much of the film’s design budget. We see several rooms, including a wood-panelled sitting room, an observation deck with large sliding blinders, both designed in the sort of plush, aristocratic style that Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea set as the blueprint for almost all Verne adaptations to come. However, there are also two other rooms, dominated by greys, glass and steel, that feel ripped from the visual world of Forbidden Planet, rather than Verne’s 19th century, adding wholly anachronistic design elements and technology. These feel just as at home in a Verne movie as smartphones would in a western.

The science if befuddling. Of course, there’s the idea that one could survive being shot out of a cannon at the velocity required to travel beyong Earth’s gravity, an idea even Jules Verne knew to be faulty – even if he devised ways to get around the problem in the novel (he had the passengers suspended on a “raft” in a water container to cushion the blow). In the film, the screenwriters have come up with a bonkers idea that the way to overcome the shock of being fired out of a cannon is to be rotated in a tube revolving 12,000 times a minute, all while in suspended animation. What kind of physics are involved in this solution is never explained. Much is made of the giant gyroscope – which is only there to “compensate for gravity”, as if a gyroscope could create artificial gravity. For some reason, when the nuclear reactor starts to melt, all the passengers’ – spring-operated – watches stop, as if radiation would affect the mechanical springs. At the finale, Barbicane and Nicholl contemplate that the reactor meltdown will cause the rocket to disintegrate. However, they reason, if the explosion is powerful enough, it will not cause the rocket to disintegrate, but somehow neatly detach all the four compartments of the rocket, that just so all happen to have functioning landing thrusters. This, again, is a train of physics that probably can’t be explained by anyone save the screenwriters.

The film’s visuals are uneven. While much of it seems out of place, the interior designs of the space rocket are very impressive, looking like they actually belong in an epic movie. One suspects that these were completed before RKO went belly-up and the budget was slashed. But otherswise, much of the film feels impoverished and cramped, despite the lush Technicolor. For example, outside the rocket interiors and a few lushly decorated mansion entrance halls, there are not many interior sets, and those that are on display often feel cramped. Scenes that are supposed to show huge gatherings of people are sometimes reduced to a dozen extras. The exteriors of space look like the matte paintings that they are and there’s never any hint at the sense of scale and wonder befitting the sort of epic the film sets out to be – not that it is reflected in the script, either. As Virginia says at one point: “This isn’t any worse than riding the train together”, which is pretty much what the film feels like.

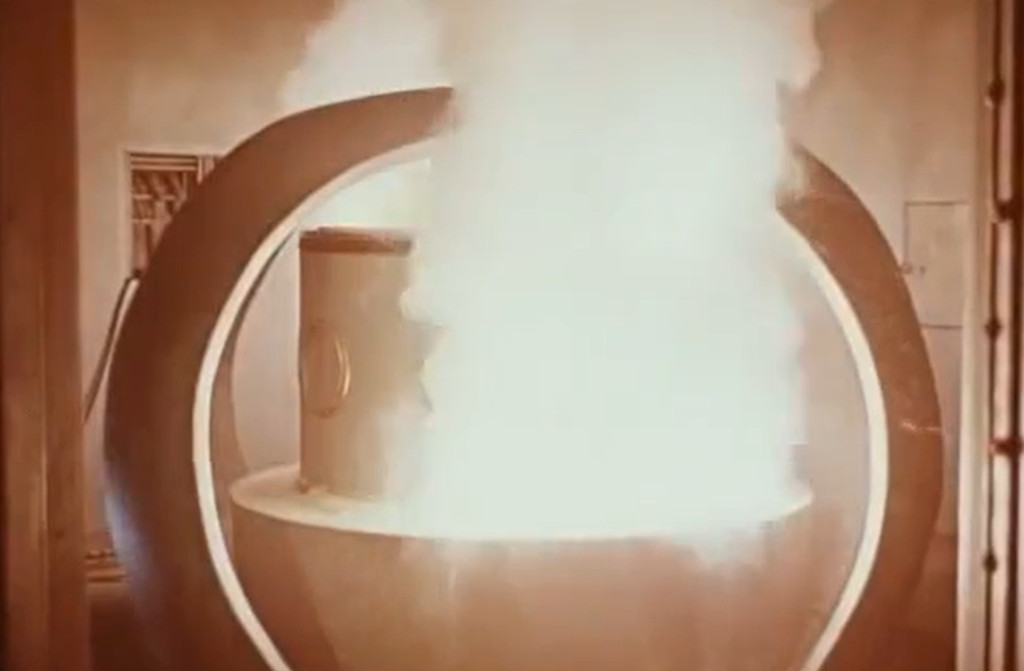

The practical effects – I should write: those that are tied to the spaceship interiors – are quite impressive, from the giant gyroscope to the rotating “acceleration tubes” and that odd orb with neon lights. But that’s where it stops. The asteroids on display outside the observation room’s window are rather disappointing sparklers, and the scenes of the rocket taking off seem to have been completed in an extreme hurry. The model rocket itself looks quite nice, but it is only ever filmed from a single angle, against a blue sky during “takeoff”. There’s never any sense of movement, and the rocket is clearly stationary the whole time – kept in place by a clearly visible support rod (it is possible this rod was hidden in the film’s theatrical widescreen presentation format). Furthermore, the flames and smoke billow up across the rocket and not downward as they would if the rocket was fired into space. This is an amateur mistake: even the cheapest of the B-movie directors knew to turn the rocket upside-down and then turn the film strip 180 degrees in editing as to simulate the flames going downward. The same unedited images ofthe rocket against a blue sky with flames rising up and over it are used at one point when it is supposed to be in the darkness of space. As for visual effects, they are almost nonexistent, save for some cel animation of electrical arcs. If the special effects are not up to specs, it is not because a lack of know-how. They were designed by Lee Zavitz, who had headed the special effects crew on Around the World in Eighty Days.

Joseph Cotten was seldom bad, and he is the most impressive actor here, trying his very best to bring life into his character. George Sanders, who was always best as smug, condescending villains, gets the worst and most bombastic lines of the movie, calling upon an emotional directness and honesty that really wasn’t in his repertoire – and even if they would have been, it’s questionable whether it would have been enough to make the lines believable. The dialogue is stilted and unnatural all the way through, perhaps in a misguided attempt to make them sound like they would have been spoken in the 19th century.

Handsome Don Dubbins is fine as the goodie-two-shoes romantic lead of the film, and brings a sincerity and naturalness to the otherwise stilted procedures. The same, unfortunately, cannot be said about Debra Paget, her beatiful, dark features covered in a stiff layer of makeup and a similarly lifeless blonde wig. Paget has little to do in the film, and the condescending script doesn’t do her or her character any favours. The rest of the characters are simply stereotypical cardboard cutouts, and performed to the heightened style of the movie by a group of capable character actors.

This was the first feature adaptation of Jules Verne’s classic 1865 and 1870 books – in fact, the first actual adaptation at all. Along with H.G. Wells‘ First Men in the Moon, the books, in particular the first one, served as loose inspiration for Georges Méliès groundbreaking special effects extravaganza A Trip to the Moon (1902, review), and several other short films of the era. But Verne’s books, with their dry scientific angle and educational tone, with very little in the form of character drama, adventure or even much of a plot, proved more or less unfilmable. They were written for an age where very little was known about space, our heavenly bodies and about how physics in outer space worked. The first book is merely a treatise on how one would go about building a rocket to the moon, intermixed with dry “drama” mostly intended to highlight the workings of international commerce and political and diplomatic tensions in the world. The second book is, more than anything, an educational fiction laying out the collected knowledge about the moon, space and space physics, such as weightlessness and the theories of how gravity and vacuum work in space.

The 1958 film has remained the only movie that can claim to be even remotely an adaptation of the novels. The 1967 movie Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon is a slapstick/caper comedy that has little to do with Verne other than the title, and the 1998 TV miniseries From the Earth to the Moon is a docudrama about NASA’s Apollo program.

As such, the film at least has some historical value. It is also only the second Hollywood adaptation in colour of one of Jules Verne’s science fiction novels, and it would be followed by several more in the late 50s.

From the Earth to the Moon is a film that might have been a fun special effects extravaganza had it been given a bigger budget – and had there actually been any fun in the script. However, as it stands, the filmmakers have been more interested in lecturing about the nuclear proliferation debate than in actually making a functioning movie. It takes ages to get off the ground, and once it does it contains none of the sense of wonder and adventure that a film about the first rocket to the moon might be expected to. The only thing it has going for it is the Thechnicolor photography and some rather impressive sets. It is not only dull, it is also confusing and riddled with pompous dialogue. Of all the Technicolor Verne adaptations of the era, this one sits at the bottom rung.

Reception & Legacy

From the Earth to the Moon premiered in November, 1958, and was neither a critical nor audience hit.

Bosley Crowther at The New York Times praised the visuals, but, “unfortunately, Robert Blees and James Leicester, who seemed to base their script more on recent data about rocket launchings than on the fantasies of Mr. Verne, made one disastrous miscalculation. They failed to compute how far this sort of fanciful nonsense required that they intrude their tongues into their cheeks. And Mr. Haskin, the director, failed to correct their mistake. As a consequence, what could have been outrageous and highly amusing in From the Earth to the Moon is merely mixed-up science fiction decked out in fancy costumes.”

The Film Bulletin wrote: “nothing much helps: the entertainment countdown for this one is a dud for almost every reel”. Harrison’s Reports opined: “If there was a little more action and a little less philosophizing, the film undoubtedly would engender a more enthusiastic audience reaction”.

In his book Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren calls From the Earth to the Moon “a dismal wrongheaded and boring movie”, “a talky, attenuated and boring movie, full of anachronistic ideas and attitudes”.

Richard Scheib at Moria gives the movie 2/5 stars, noting that director Haskin normally “had a good, if sometimes stolid, eye for Technicolor drama and special effects spectacle” and that the film is “reasonably lavishly produced”. But: “From the Earth to the Moon is nearly a good film. Almost, but not quite. It befalls the critical lack of nerve of most 1950s science-fiction films – that is they fall into self-absorption (with the end of the world, the threatening nature of the rest of the universe and The Bomb) and fail to take the imaginative leap out beyond the Earth to conquer the universe as seemed eminently within the imaginative grasp at the beginning of the decade”.

However, this is pretty much as good a review for the film that you’ll get from serious critics. Dave Sindelar says: “the movie as a whole just seemed vague and unfocused; it never really comes to life, despite a cast that could have easily made it more engaging and situations that had a real potential for some strong drama. All in all, one of the least satisfying of the Verne adaptations.” Kevin Lyons at The EOFFTV Review says it is “a difficult film to like despite having so much going for it”.

From the Earth to the Moon created no ripples in Hollywood. That other Verne adaptations followed were no more than a continuation of success of Around the Worlds in Eighty Days, and today the film belongs to obscurity.

Cast & Crew

I have written about several films based on or inspired by Jules Verne, but have yet to write much about the author himself, so let’s take this opportunity to remedy this omission. Verne was the Frenchman who trained as a lawyer but then defied his father by not going into the family business, instead chasing his dream to become an author. He made his literary debut in 1849, at the age of 21, and worked as a writer of plays, stage shows, short stories and science pieces before publishing his first novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon, in 1863, setting the template for Voyages Extraordinaires, that would become ingrained in both adventure and science fiction literature and film. Verne’s aim was “to outline all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format that is his own, the history of the universe”. To this end, of course, it was only natural that one of his earliest novels should take the reader to the moon. From the Earth to the Moon was published in 1865, and despite its somewhat wooden character, belongs squarely among Verne’s early, playful and optimistic novels, as does its sequel Around the Moon (1870).

By 1970 Jules Verne had already published many of his classic works in only seven years; Five Weeks in a Balloon, Journey to the Centre of the Earth, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, From the Earth to the Moon, In Search of the Castaways, 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas and A Floating City. In the next decade to come, several classics would follow: Around the World in Eighty Days, The Mysterious Island, Michel Strogoff, Off on a Comet, Dick Sand, a Captain at Fifteen, The Begum’s Fortune and The Steam House. He also continued his work as a playwright, which was actually where he made most of his income. His stage adaptations of Around the World in Eighty Days and Michel Strogoff were hugely popular in Paris, and by the mid 70s, he was able to support himself financially on his writings. But while popular with both the audience and to some extent with critics, his popularity cast him as a mainstream writer in the adventure genre, which gave him little merit in academic and literary circles, a fact that would remain constant during his entire life, and one which saddened Verne deeply. This reputation wasn’t helped by the fact that his books were getting mauled by the English translations, with English and American translators rewriting his books to fit the publishers’ intentions of marketing Verne as a children’s author, often omitting large chunks of scientific and political content, simplifying his language and in general doing a shoddy work of the translation.

However, his success led to both wealth and fame, and Verne was able to buy a sail boat with which he sailed around Europe, and also travelled frequently otherwise, including trips to the USA, a country that fascinated him greatly (several of his novels are set in the US, with American protagonists). He kept up his prolific writing pace, publishing at least one novel every year until his death in 1905. Still, on a personal level Verne was beset by several unhappy circumstamces. His relationship with his son Michel had been strained for most of their lives (even if they grew closer with time). In 1886, his longtime publisher and collaborator Pierre-Jules Hetzel died, and Verne was shot by his mentally ill nephew Gaston. The attack resulted in a leg injury which caused Verne pain for the rest of his life. In 1887, his mother, to whom he was very close, also died. As a result, his books grew darker and more pessimistic in his later years, seen particularly in novels such as An Antarctic Mystery, The Village in the Treetops, A Drama in Livonia, and not least the brooding Master of the World, in which Verne’s previously “noble” villain Robur has turned into a tyrannical terrorist. No doubt Verne’s bleaker outlook on the world and the future was also informed by current developments, such as the Dreyfus affair which rocked France for a decade, and the general unrest in the world, with authoritarianism as well as anarchism and socialism on the rise, and the European powers rattling their sabres at each other in anticipation of WWI.

Verne’s legacy has been contested. His popularity during his lifetime, writing books that were primarily viewed as light entertainment or geared towards a juvenile audience, left a long shadow over his writings, not helped by the sub-par English publications of his books, which dominated the international market for much of the 20th century. However, scholars in France, many of them connected with the rising avantgarde movement, re-evaluated Verne’s writings both in terms of style and content in the 1960s, and his literature became accepted as object for serious literary scholarship. It wasn’t until the 1980s that perceptions of Verne also started to changed in the anglophone world, and a Verne renaissance started to appear, with several new translations that stayed true to the original French works.

Together with Mary Shelley and H.G. Wells, Jules Verne is generally credited as one of the progenitors of the science fiction genre, however, there has been much debate over whether the writings of Verne should be considered SF or not. Verne didn’t have any scholarly background in science, but was a voracious reader of scientific literature and researched all his novels meticulously. However, noted French scholar and science fiction pioneer Maurice Renard argued as early as 1909 that Verne never wrote a single line of science fiction. Renard was perhaps the first person to make a serious attempt at defining science fiction as a distinct genre of its own, one which he christened “scientifique-marveilleuse”. According to Renard, Verne never truly extended his science into the unkown, for example speculating about life on Mars or time travel, but rather used already existing science and supersized it, or took projects that scientists were currently working on and “simply supposed them already born before they actually were”. For example, imagining a submarine at a time when such were already being built was, in Renard’s mind, not scientifique-marveilleuse. And while the notion of science fiction as a genre was not established in Verne’s lifetime, he himself protested against the idea that he would have “invented” anything or tried to predict the future of science or technology.

Verne was vehement that any scientific accuracy in his books was down to researching existing science, rather than extrapolating new science from it, and that any technological breakthroughs he may have predicted were “mere coincidences”. Furthermore, he often used pseudo-science or inaccurate science in his books that even he didn’t ascribe to. For example, he said: “I wrote Five Weeks in a Balloon, not as a story about ballooning, but as a story about Africa. I always was greatly interested in geography, history and travel, and I wanted to give a romantic description of Africa. Now, there was no means of taking my travellers through Africa otherwise than in a balloon, and that is why a balloon is introduced […] I may say that at the time I wrote the novel, as now, I had no faith in the possibility of ever steering balloons”.

Likewise, one could imagine that Verne didn’t really think one could construct a submarine as big as an apartment block or a propeller-powered airship as big as a man-o-war. He probably didn’t think one could shoot a crewed missile to the moon from a cannon, or that prehistorical creatures lived in a hollow Earth which could be reached via a volcano.

Of course, Renard’s definition is only one of numerous definitions of science fiction, and the debate over what constitute the parameters of the genre is one that will never get a definitive answer. Whether you define Verne’s work as SF or not, he most definitely contributed to the rise of the genre – and without Jules Verne there probably wouldn’t have been either a Renard or a Wells, and the history of science fiction would have looked very different.

Director Byron Haskin is another science fiction notable that I have not written much about, despite him being one of the most important directors in the genre in the 50s. Californian Haskin begun his movie career as a cinematographer and occasional director in the silent era, but gravitated towards special effects, eventually working as the head of Warner’s special effects department between 1937 and 1945. He returned to directing in the late 40s, and in 1950 directed Disney’s live-action classic Treasure Island, which, among other things, forever defined “pirate speak”.

It was probably the family-friendly epicness of Treasure Island in combination with his prowess as a special effects creator that made producer George Pal approach Byron Haskin for his 1953 science fiction extravaganza The War of the Worlds (review), based on the writings of H.G. Wells. The film became a huge success, redifing special effects in Hollywood, and would remain the commercial pinnacle of the 50s science fiction cycle. Following the successful collaboration, Haskin made three more films for Pal: the adventure/killer ant film The Naked Jungle (1954), the the ambitious misfire Conquest of Space (1955, review) and later the telekinesis murder movie The Power, which would remain his last film. The flopping of Conquest of Space hurt Byron’s career, and while still occasionally courted by major studios, he made mostly B-movies after this, and was forced to branch out to television to make ends meet. He probably hoped that From the Earth to the Moon (1958) for RKO was to be another hit along the lines of The War of the Worlds, but was stuck with a sub-par script and slashed funding when RKO folded – and the movie became both a critical and box office flop. In 1960 20th Century-Fox put him in charge of the underwater adventure drama September Storm – an otherwise unremarkable film about a team scuba diving for lost treasure, but for the fact that it was filmed in the short-lived Stereo Vision format, which was a novel combination of 3D and widescreen. For Paramount Haskin made Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), which he named as a favourite among his own films, because he thought it had a sound story. While it is regarded as a flawed but interesting cult classic today, at the time of its release it flopped – according to Haskin because Paramount bungled the marketing.

For TV, Haskin was one of the key players behind the popular, and accomplished, science fiction/mystery series The Outer Limits, supervising the show’s special effects and effectively working as an uncredited producer, and also directed several episodes, including the Harlan Ellison-scripted “Demon With a Glass Hand”. He also worked as a technical advisor and associate producer for the original Star Trek pilot “The Cage”. However, Haskin and showrunner Gene Roddenberry didn’t get along, reportedly because Roddenberry tried to push Haskin into producing effects that Haskin didn’t think feasable, and Haskin thinking Roddenberry didn’t know what he was doing.

Byron Haskin did film and TV in pretty much all genres, with the exception of musicals and horror, but he gravitated towards adventure and science fiction. As a technician and effects creator, he was one of Hollywood’s finest. He did his first directorial jobs on the cusp of the sound era, ushering in the talkies, and was nominated for Oscars for best special effects in four consecutive years between 1940 and 1943. In 1939 he won a technical Oscar for the development of a new kind of background projector. His greatest achievement is no doubt The War of the Worlds, a pioneering work of cinema, despite its scripting problems, and it is ironic that the one film he worked on that would win the special effects Oscar was one where he wasn’t credited for the effects. However, as a dramatic director, Haskin was pedestrian. John Brosnan writes as the SF Encyclopedia: “His work as a director was likeable […] but uninspired: War of the Worlds derives impact from its spectacle, but most of his other sf films are merely competent.” Haskin retired in 1968, and passed away in 1984.

Since I’ve taken up so much of your time with biographies over the author and director, I’ll try to keep the actors reasonably short. From the Earth to the Moon had big-name stars, or at least one-time big name stars that few science fiction movies of the era could boast.

Joseph Cotten had once been one of the biggest stars of the silver screen. A stage actor, Cotten came up through the ranks alongside Orson Welles in the Mercury Theater, and when Welles got the chance to direct his first movie, Citizen Kane (1941), he cast Cotten as his co-lead. Welles subsequently cast him in the lead in his following two movies, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and Journey Into Fear (1943). By now, Cotten was a bona fide movie star and got the chance to play both romantic leads and villains. The 40s was the highlight of his career, and he starred in such films as Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), William Dieterle’s Duel in the Sun (1946) and Portrait of Jennie (1948) and Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), again teaming up with Welles.

While he remained in demand, the 50s saw a dip in his marquee value, as Cotten neared and passed his 50th birthday, and his attraction as a romantic lead lessened. He made two more films with Welles in the decade: The Tragedy of Othello: the Moor of Venice (1951) and Touch of Evil (1958), and thrived in the new TV playhouse format, which provided him with the opportunity to do theatre plays for television. The 50s also saw the first of his not infrequent encounters with science fiction, the impoverished and muddled would-be epic From the Earth to the Moon (1958). The 60s and 70s saw Cotten divide his time between TV and movies, appearing in both quality dramas and not-so-quality low-budget fare. He appeared in a few highly publicised films that gathered togother all-star casts of star of Hollywood past, like the crime dara Hush…Hush, Sweet Caroline (1964) and Airport ’77 (1977) and co-starred in the Pearl Harbor epic Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). And in 1980 he co-starred in Michael Cimino’s period piece Heaven’s Gate.

Among hos quirkier projects were the horror comedy The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971), opposite Vincent Price, the Italo horror Baron Blood (1972) and the horror movie The Survivor (1981), which was to be his final film. In 1969 Cotten co-starred in the Japanese underwater sci-fi movie Latitude Zero, and in 1971 appeared in the TV movie City Beneath the Sea. He got the chance to play Baron Frankenstein in another Italo horror, Lady Frankenstein, the same year. In between his many spaghetti movies he also had a supporting role as the first person to die after learning the secret of Soylent Green (1973). And in 1979 he was back with the Italians in a small role in Island of the Fishmen.

George Sanders was an star of the same calibre as Joseph Cotten. Born into a rich Anglo-Russian family in St. Petersburg in 1906, he found himself in London after the Russian revolution in 1917, and after a string of odd jobs took up acting. His stage work took him to Broadway in 1934, and here he got cast as the villain Lloyds of London (1936). Sanders, with his aristocratic bearing, condescending attitude and low barytone, was perfect for the role, which earned him a 7-year contract with Fox.

Sanders would spend the rest of his life in Hollywood, alternating between leads and supporting roles, often in villainous parts, but with the odd heroic role thrown in the mix. In the 30s and early 40s, Sanders played the lead in a series of films about the gentleman thief and maverick The Saint, and its copycat series The Falcon. He was in demand during the 40s, appearing in such movies as Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt (1941), Otto Preminger’s Forever Amber (1947) and Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah (1949). He continued his successful career in the 50s, winning a supporting actor Oscar for his turn as the villainous theatre critic in All About Eve (1950). He starred in the Technicolor swashbuckler Ivanhoe (1952) and played leads in Witness to Murder (1954), Journey to Italy (1954), Moonfleet (1955), Death of a Scoundrel (1956) and Solomon and Sheba (1959). In the 60s he continued to alternate between A and B movies, with a smattering of TV in between, and was in demand for adventure films, such as The Last Voyage (1960), the Jules Verne adaptation In Search of the Castaways (1962), in which he played the iconic Tom Ayrton, Cairo (1963), for which he was top-billed, and last but not least Disney’s animated classic The Jungle Book (1967), which immortalised him as the voice of Shere Khan. This was also the decade in which Sanders appeared in two of the genre films he is best remembered for. In 1960, he played the heroic lead in Village of the Damned, and in 1964 played the millionaire in whose house several murders occur in the Pink Panther movie A Shot in the Dark.

By the mid-60s, Sanders‘ opportunities to work in A-movies had dried up, and he was consigned to B-films. He announced hos retirement in 1969, but appeared in a handful of low-budget movies in the early 70s, possibly because he needed the money. Some years earlier, he announced his bankruptcy due to bad investments. In 1972 he committed suicide, possibly due to depression caused by the death of his third wife and several family members, as well as his financial predicament and his failing health.

George Sanders‘ science fiction films include Things to Come (1936, review), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Village of the Damned (1960), The Girl from Rio (1969), The Body Stealers (1969) and Doomwatch (1972). He was also first-billed in the cult horror movie Psychomania (1973), his last movie.

Spurred on by her mother, a former minor actress and dancer, Debra Paget entered showbiz at the age of 8 and got a 7-year contract with 20th Century-Fox at the age of 14, in 1948. After a few minor roles, she was offered a female lead oppposite Jimmy Stewart in the western Broken Arrow (1950), as a Native American maiden. The film was a commercial and critica success, and would set the tone for Paget’s career. She played Native American maidens in at least three other films, and was often cast on other roles as exotic beauties, be it Hispanic, Italian, Polynesian, Indian, Hebrew or Egyptian. While Fox’ movie Princess of the Nile (1954) wasn’t a huge success, Paget in the title role turned heads, as did her role as Lucia in Demitrius and the Gladiators (1954) and as as the water girl Lilia in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956). After her contract with Fox ran out in 1956, Paget primarily appeared on TV and in B-movies. One interesting detour was when Fritz Lang, upon his return to Germany, cast her as the alluring dancer Seetha in the lead of his two adventure epics Der Tiger von Eschnapur and Das Indische Grabmal, both released in 1960. She also appeared in two horror movies directed by Roger Corman – Tales of Terror (1962) and The Haunted Palace (1963).

Debra Paget appeared in three science fiction movies. She had an uncredited bit-part in the SF comedy It Happens Every Spring (1949, review), and starred in From the Earth to the Moon (1958) and Most Dangerous Man Alive (1961). She retired from acting after marrying in 1965.

Fair-haired Don Dubbins, who plays the romantic “lead” in From the Earth to the Moon was an occasional co-lead and later character actor and TV guest star active between the early 50s and the early 90s. After minor roles in his first Hollywood years, James Cagney took him under his wing and featured him in large roles in his films These Wilder Years (1956) and Tribute to a Bad Man (1956), and he also had co-leads in Jack Webb’s war film The D.I. (1957), From the Earth to the Moon (1958) and the adventure movie The Enchanted Island (1959). This was the pinnacle of his career, and come the 60s, he mainly worked as a guest actor on close to 100 TV shows, with a few movie bit-parts in between. He had a featured role in the Ray Bradbury adaptation The Illustrated Man (1969).

The rest of the cast is filled up with capable performers. Patric Knowles was a dashing leading man in the 30s, who played co-leads in The Wolf Man (1941) and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943, review). Carl Esmond, who plays “Jules Verne” in From the Earth to the Moon (1958) was a respected character actor who had his heyday from thr late 30s to the early 50s with prominent roles in a handful of A-movies, and later became a frequent TV guest star. Gaunt, sardonic Henry Daniell enjoyed a thriving stage career before making his film debut in 1929, and became a go-to actor for villanous and unpleasant characters. Two of his most famous roles came in 1940. He played Errol Flynn’s foil Lord Wolfingham in the swashbuckler The Sea Hawk and charicatured Joseph Goebbels as “Garbitsch” in Charles Chaplin’s masterpiece The Great Dictator. His other memorable supporting roles are too many to mention. He also had small roles in the transportation-themed SF movies From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961) and Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962).

The film also features science fiction stalwarts Morris Ankrum (as president Grant), Robert Clarke (as narrator) and Les Tremayne (as countdown voice). Click the links for more on them.

Janne Wass

From the Earth to the Moon. 1958, USA. Directed by Byron Haskin. Written by Robert Blees & James Leicester. Based on novels by Jules Verne. Starring: Joseph Cotten, George Sanders, Debra Paget, Don Dubbins, Patric Knowles, Carl Esmond, Henry Daniell, Melville Cooper, Ludwig Stössel. Music: Louis Forbes. Cinematography: Edwin DuPar. Editing: James Leicester. Production design: Hal Wilson Cox. Costumes: Gwen Wakeling. Sound: Weldon Coe. Special effects: Lee Zavitz. Visual effects: Walter Simpson. Produced by Benedict Bogeaus for RKO & Warner Brothers.

Leave a comment