Ismail Yassin sits on the controls of a space rocket and lands on the moon where he and his two co-passengers are met by a robot, a scientist and a group of scantily clad dancing women. If not for Yassin’s incessant shouting and mugging, Egypt’s first space film “Journey to the Moon” from 1959 might have been a decent SF spoof. 3/10

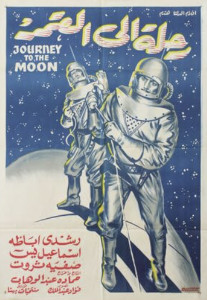

Rihlah ela el-Qamar. 1959, Egypt. Directed & written by Hamada Abdel Wahab. Starring: Ismail Yassin, Rushdy Abaza, Edmond Tuima, Safiyya Tharwat. Produced by Hamada Abdel Wahab. IMDb: 5.2/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

In Cairo, eccentric German scientist Mr. Sharfin (Edmond Tuima) is about to launch the first rocket to the moon. Astronomer Ahmed Rushdy (Rushdy Abaza) is on site interviewing Sharfin, when the local newspaper’s driver Ismail (Ismail Yassin) sneaks onto the rocket taking pictures in secret. Sharfin beleives him to be a spy, and attacks him. In the kerfuffle, Ismail sits on the controls, accidentally sending the rocket into space, with him, Sharfin and Rushdy on board. Unfortunately the only person cabable of actually flying the thing – Sharfin – is knocked over the head and becomes catatonic.

Rihla ela el-Qamar, or Journey to the Moon, as it has later been released as in English, is not Egypt’s first science fiction movie, but one of the very earliest, and the country’s first (and only) space film. Directed, written and produced by Hamada Abdel Wahab in 1959, it is a comedy/spoof featuring “Egypt’s Jerry Lewis“, Ismail Yassin.

With death in the darkness of space looming, Ismail decides to do what he does best – get drunk – and he will stay in his state of intoxication for the rest of the adventure. However, after many an effort, he and Rushdy finally manage to wake up Mr. Sharfin, who takes control of the rocket and manages to set it down on the moon. Unfortunately, he has miscalculated his fuel consumption, and it looks like our mismatched trio are destined to stay indefinitely on the lunar surface. Fortunately, they are picked up by a robot, Otto, who brings them to his master, scientist Dr. Kosmo (Ibrahim Younis) and his menagerie of 20-something girls in mini skirts and deep cleavages.

Dr. Kosmo explains that he and his girls (daughters?) are some of the few survivors of a devastating nuclear war (on the moon?), and that they have an abundant source of radioactive fuel that Mr. Sharfin can use to get the team home to Earth. However, it requires an arduous trek through the lunar desert to get to the cave where the last soldiers of the war keep it guarded. Otto is supposed to be the trio’s guide, but Ismail pours booze into the robot until it explodes, so one of the girls, Stella (Safiyyah Tharwat), who has been romanced by Rushdy, agrees to take them. After an uneventful desert trek (Rushdy and Stella kiss, Sharfin and Ismail shout at each other), they reach the cave, and are met by a group of horribly maimed soldiers, who tell our adventurers that their fate awaits everyone on Earth if they do not use “the atom” wisely. When Ismail and Sharfin go to fetch the atomic fuel, Ismail shouts so loud that he causes a cave-in. When Rushdy and Stella arrive, the believe their friends to have perished, retrieve the fuel and head for their rocket. With all the lovely girls aboard, looking to start a new life on Earth, the rocket takes off.

But: Ismail and Sharfin have survived, and are trekking their way through the lunar landscape, hoping that Rushdy might spot them as he flies past…

Background & Analysis

I have practically no background information on this film, apart from what little IMDb and Egyptian Wikipedia provide, which is not much else than a list of the cast and crew and a short plot synopsis. It was released in 1959 under the Arabic title رحلة إلى القمر, which according to Google Translate is approximately “Rihlat ‘iilaa alqamar” in Latin letters, and translates to “Journey to the Moon”. On IMDb and other movie sites it is transliterated as Rihlah ela el-Qamar, so that’s what I’m going with.

This is sometimes labelled as Egypt’s first science fiction movie. This depends on what you accept as science fiction – there’s a handful of films made in Egypt during the 50s that are tagged as science fiction on IMDb. According to plot synposes, I’m not convinced all of these cut the muster – at least one has a dream frame, which kind of disqualifies it. I have only found one of these for home viewing, Min aina laka haza? from 1952, which I have reviewed. This is a variation on The Invisible Man, and should certainly be categorised as SF, as it deals with an invisibility potion developed by a scientist. Consequentlty Rihlah ela el-Qamar can not be considered Egypt’s first SF movie, but it is the country’s first – and only – space movie.

Although largely marginalised today, in its heyday Egypt’s movie industry was a powerhouse on par with Hollywood. Egypt was the dominating cinema in Middle-Eastern and Arab countries, and its movie stars were known all over the region, some of them, like Omar Sharif, reaching a Western audience. Egypt was also where actors and music artists of the rest of the region went in search of stardom. The dominating genre was the musical. But genre cinema also found an audience, especially in the cheap so-called Third Class cinemas, where comedies and action films went down well. Most genre pieces of the time were cheap Hollywood ripoffs, especially of Universal creature features, which were the genre films most frequently imported to Egyptian movie theatres.

Among the first Egyptian genre films (excluding some Arabian Nights-styled fantasies) were Husain Fawzi’s Tarzan/gorilla film Nadouga (1944) and Niazi Mostafa’s The Vanising Cap (Taqiat ul-ikhfa, 1944). Mostafa was a huge fan of Universal visual effects wizard John P. Fulton’s invisibility effects, and studied the techniques closely and first put them to use in The Vanishing Cap, and Return of the Vanishing Cap (1946), two films which he remade in 1959 as The Secret of the Vanishing Cap. But these were more fantasy than sci-fi. Closer to SF was probably El Sab’a Afandi (“Mr. Seven”, 1951). From the short plot synopses I have found, the film features a dream sequence in which the protagonist can walk through walls. A few directors like Hasan Ramzi also turned out a few demon and genie horror films in the late 40s but it really wasn’t until the 50s that the horror genre established itself – and still mostly combined with comedy (not unlike some Universal efforts). Worthy of mention is Haram alaik (“Shame on you”), which is described as an Egyptian version of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), starring Ismail Yassin. Yassin was also the co-lead of Egypt’s first bona fide SF movie, Min aina laka haza? (“Why do I always have to?”) from 1952.

As such, Rihlah ela el-Qamar should be viewed as a continuation of Ismail Yassin’s comedies where he took on different Hollywood genres or tropes in the style of the Three Stooges or Abbott & Costello. The movie was written, produced and directed by Hamada Abdel Wahab for his own company Delta Films. Wahab had a long working relationship with Yassin, having worked with him both as a director and assistant director.

Many of Ismail Yassin’s films were made in the mold of the Martin and Lewis comedies, with Yassin playing the comedic foil to the film’s straight man. However, Unlike Jerry Lewis, Yassin didn’t have a regular Dean Martin at his side, but would team up with different popular leading men. In the case of Rihlah ela el-Qamar, this was Rushdy Abaza, one of Egypt’s biggest romantic movie stars, who was at the top of his career, having starred in several leads opposite the country’s most popular actress, Faten Hamama. Joining Yassin and Abaza in the movie was Edmond Tuima as the German scientist and Safiyyah Tharwat as Stella, the female lead. Tuima, who naturally spoke Arabic with a French accent, was typecast as foreign characters in Epyptian films, and Tharwat was a pioneer of women’s sports in Egypt, as well as an occasional actress.

Rihla ela el-Qamar came at the heels of the 50s science fiction craze, and as such, Egypt came rather late to the space spoof party in 1959. The film doesn’t seem to be taking its inspiration from any film in particular, but rather plays with different tropes of the genre. Much of it dates back to the very earliest space films. Both the tropes of the “accidental astronaut” and the “rocket stranded on the moon” go back all the way to 1928 and Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon (review), as does the idea of “hidden treasure” in some moon cave. These tropes were then replicated in numerous Hollywood productions, starting with the very first entries, such as Destination Moon (1950, review) and Rocketship X-M (1950, review). For most of the 20th century, pulps and comics imagined planets inhabited by scantily clad young women yearning for the company of Earth men. On film, the idea was cemented by Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), setting up the enduring trope of a group of young, lovelorn women greeting visitors from Earth in scant clothing and with interpretive dance routines. Usually this type of film also presents the women as a threat to the (male) astronauts, and some palace plot or other is mostly present, however, these aspects are absent from the first Egyptian moon voyage. A clear influence of Rihla ela el-Qamar also seems to have been Forbidden Planet (1956, review). Both feature a mysterious scientist living on a celestial body with a young woman/young women and a robot servant. In Forbidden Planet, one of Robby’s neatest party tricks was his ability to produce endless amounts of booze. In a clever reversal in Rihlah ela el-Qamar, Otto is destroyed by Ismail pouring too much booze into him.

As to the style of Ismail Yassin’s comedy, it can be described as loud and grating with a lot of face pulling. From what I’ve seen, the quality of his antics are determined by the quality of the script. It worked well in Min aina laka haza? in which Yassin’s character was more of a comic sidekick who served the gangster/romance plot at the centre of the movie. In Rihlah ela el-Qamar, Yassin takes centre stage in a script that lumbers from one scene to the next and in which Yassin’s antics seem to be the focus, but in which his character isn’t allowed any meaningful journey. As written, Yassin’s only role in the film is to first screw up, then drink himself into a stupor while loudly lamenting his situation. This could work as a character presentation, but when it fills the entire film, it simply becomes annoying. At his best, Yassin could be an outstanding mugger in service of a story, but his talents are wasted here, when he is only allowed to present his loudest and most grating schtick for the entirety of the picture’s running time.

The situation isn’t helped by the introduction of Edmond Tuima’s German scientist, Mr. Sharfin, who does his best to out-shout Yassin with a similarly one-sided performance. The central idea is not bad: Ismail and Mr. Sharfin are deadly enemies for most of the film, but reconcile in the end when they overcome their differences and work together to survive. But it’s a little too late when the two characters have been portrayed as one-sided comic-book caricatures throughout the whole movie, and their softening towards the end feels calculated. Tuima’s performance as such is a strong one, but he is thwarted by a bad script – it is supposed to be funny that he shouts “Fantastisch! Wunderbar!” in a high-pitched voice every two minutes – and the fact that the combination of his and Yassin’s histrionics don’t so much cancel each other out, but causes the movie to explode in a cacaphony of noise, leaves the viewer exhausted halfway through.

There’s a surprisingly sober and haunting moment toward the end of the movie, amid all the comical references and spoofings, and the low-brow histrionics of Tuima and Yassin. The scene in which our heroes find the guardians of the nuclear fuel in the cave, and are warned to use it with caution, is played straight and with surprising effect. Real amputees are used in the roles of the maimed soldiers guarding the “treasure”, and the effect of the scene is heightened by some good makeup work and stark lighting. This nuclear-age warning is one of the most sombre and effectful ones seen in a 50s movie, but it is completely out of place in Rihla ela el-Qamar, as if it was cut and pasted from another film entirely.

Producer/writer/director Hamada Abdel Wahab has clearly put some effort into the film. As opposed to practically all Hollywood space films of the era, he has actually built a the rocket as a full-size set piece, seemimgly standing around 50 feet tall, with a functioning winch-operated “elevator” that the actors use to get in and out of the rocket. The cockpit of the rocket is the usual array of gauges, buttons and levers from low-budget Hollywood films, but Wahab needn’t be ashamed of the design in comparison with American counterparts. On the down side, the moon looks strikingly like the Sahara, but at least it doesn’t look like Bronson Canyon. All in all, the movie is surprisingly well filmed, there’s even a space walk à la Destination Moon that’s fairly well executed, given the circumstances.

Because of the way fundamentalist versions of Islam have influenced so much of West’s image of the Arab world, it’s always a bit of a jolt to be reminded that this was not always the case. And even though I know intellectually that throughout most of its existence as a modern state, Egypt has been secular, it still surprises me to see how liberally sex and drinking is portrayed in a movie from the 50s. When it comes to the outfits and dance moves of the ladies in the film, Rihlah ela el-Qamar is in no way any more chaste than its Hollywood counterparts, and when it comes to boozing, I suspect that the Hays code censors would probably have asked the producer to tone down Yassin’s perpetual drunkenness.

I have said little about the rest of the cast, mainly because Yassin and Tuima dominate the movie so much in my head. But the two other lead characters – the romantic leads – both come off to their advantage. Charming, charismaticRushdy Abaza takes the science fiction stuff as seriously as his straight man role requires, and resists the temptation of winking at the audience. And in his interaction with Safiyyah Tharwat you can see why he was considered one of the great heart-throbs of Egyptian 50s and 60s cinema. And Tharwat, by all accounts a remarkable woman in her own right, has her own magnetism, a light-hearted, playful charisma that is hard to resist. It’s a shame she only acted in a handful of movies. Gaunt character actorIbrahim Younis is also memorable as the mysterious Dr. Kosmo.

In an interesting post about Arab sci-fi, Rand Al-Hadethi says that Rihlah ela e-Qamar “marked a pivotal moment in Egyptian cinema toward traditional science fiction”. The article, which explores the way in which Arab artists have analysed the world and society through speculative fiction, states that the late 50s “coincided with president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s push for modernisation and Arab nationalism, with the film arguably channelling Egypt’s aspirations and anxieties amid rapid social change”. I’d say that “arguably” is the central word here. Apart from the short bit with with the nuclear-maimed soldiers, there is little in the movie that could possibly be perceived as any sort of social or political comment.

Rihlal ela el-Qamar is an interesting film simply because of its existence as Egypt’s, the Arab world’s, and Africa’s first space movie. As such, it is also much better and more competently put together than Turkey’s first SF movie Flying Saucers Over Istanbul (1955, review), which is not a particularly high bar, as I gave that film zero stars. On the other hand, if not for the fact that it is made in Arabic, there’s nothing in the movie that identifies it as an Egyptian film, as it is entirely modelled on its Hollywood inspirations. Even the dance sequences are choreographed in modern, Western style.

The attention to designs and sets – particularly the full-size rocket – is primarily what helps Rihlal ela el-Qamar redeem itself. There are a few funny and entertaining sequences in the first third of the movie, before the shouting of Edmond Tuima and Ismail Yassin starts getting on your nerves. The comedy is largely built upon the mugging and shouting of these two actors as well as Ismail’s drunkenness and cowardice. Aside from the comedy, it is like watching a bad Hollywood space B-movie with a twist, but a twist that doesn’t really bring anything new or interesting to the table. While definitely not the worst film we have reviewed here, it is something of a chore to get through. Interesting for its country of origin, but with little else to recommend it.

Reception & Legacy

Unsurprisingly, I have found no contemporary reviews for the movie. It was released in Egypt in April, 1959, and because of Ismail Yassin’s star status, was probably distributed in much of the Arab-speaking world. It has since been released on DVD and is available online. Some releases give it the title A Trip to the Moon.

Few are also the modern reviews I can find, but there are some. One thing they all have in common is that none of the critics think that Ismail Yassin is funny. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings gives the film the benefit of a doubt, noting that the comedy might have been lost in translation, but ultimately: “That it’s a comedy is obvious, and that Ismail Yassin is the primary comic personality here is apparent. But I find myself not laughing.” Todd Stadtman at Die, Danger, Die, Die, Kill! writes: “As inherently hilarious as cuckoldry, chronic alcoholism, fascism, and the ravages of nuclear war may be, I found very little to really laugh at in A Trip to the Moon.”

Still, modern critics seem to have a bit of a soft spot for the film. Stadtman writes that he found it “immensely entertaining”, partly because of its novelty as an Egyptian 50s space movie, and notes that it is professionally made. Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster says: “I enjoyed Journey to the Moon a lot more than I expected to […]. It just looks and feels like an early Fifties science fiction classic.” Sindelar is not as forgiving: “for the most part, this falls flat”.

Rihlah ela el-Qamar did not start a trend of Egyptian space or science fiction films. In fact, as far as I can tell, this is the country’s only space film. Egyptian science fiction as a genre has remained in the margins to this day, with only a couple of SF movies released per decade.

Cast & Crew

Writer/director/producer Hamada Abdel Wahab directed a small handful handful of movies in the 50s, and was primarily an assistant director. He had his hands in a number of films starring Ismail Yassin. His most lasting legacy to Egyptian cinema is the country’s only space movie. When Egypt got its first national TV station in 1961, Wahab was among the pioneers of the medium. He produced and directed many TV shows, and in 1980 he was appointed head of Channel 1 (ERTU 1).

The spelling of Ismail Yassin’s name keeps changing on IMDb. When I reviewed Min aina laka haza? (1952), it was spelled Yasseen. Now it is spelled Yassin. Wikipedia spells it Yassine. Whatever the spelling, Yassin was Egypt’s top comedy star for decades. Born in 1912, he made a name for himself as a standup comedian performing at the biggest clubs in Cairo in the 30s and 40s. This is when he formed his lifelong professional partnership with writer Abu Al-Saud Al-Ibiary, who went on to write most of his famous films. Renowned for his rubber face and his self-depreciating humour, he entered the movie business in the late 30s, primarily as a supporting comic relief. However, in the 50s he began carrying his own films, many of them based on the classic Abbott & Costello formula (Ismail Yassin in the Navy, in the Police, in the Mental Hospital, etc).

In 1951 he starred in The Haunted House, in 1954 in Ismail Yassin and the Ghost and Ismail and Abdel Meet Frankenstein, in 1958 in Ismail Yassin as Tarzan and in 1959 he starred in the rare Egyptian space film Rihlah ela el-Qamar (“Journey to the Moon”). Yassin’s wide grin and over-the-top facial expressions coupled with plasticity and slapstick sensibilities makes him something of a proto–Eddie Murphy, or perhaps an Egyptian Jerry Lewis. He carried his movie fame with him to the stage in 1954, when he founded his own theatre troupe, who would perform over 50 comedy plays up until 1966. Yassin passed away in 1972, only 59 years of age.

The male romantic lead of Rihlah ela el-Qamar, Rushdi Abaza, had to fight for his reputation as one of Egypt’s greatest movie stars in more than one way. Hailing from the aristocratic Abaza family, he met great resistance not only from his father, but from the whole family, when he entered the movie business in the early 50s, as artistic endeavours were not seen as a worthy profession for an aristocrat. With support from his mother, he soldiered on for nearly ten years in films without any greater success, often having to work other jobs on the side. At one time dreaming of becoming a body builder, Abaza had an athletic build and was often cast in roles of a handsome ruffian. His career took an abrupt turn when legendary director Ezz El-Dine Zulficar saw something special in Abaza, and cast him in the more mature role of the lead in A Woman on the Road (1958), which instantly turned him into a star. Shortly after he starred in the great Yousseff Chahine’s classic revolutionary epic Jamila, the Algerian (1958), and throughout the 60s and early 70s he was the star of many films depicting African independency and freedom struggles, many of which are considered among the greatest films of Egypt. Before his shot to fame he had a small role in The Ten Commandments (1956), partly shot in Egypt. He was considered for the role of Sherif Ali in Lawrence of Arabia (1962), but it ultimately went to Omar Sharif. He also had offers to follow in Sharif’s footsteps and try his luck in Hollywood, but wasn’t interested in leaving his home country. Abaza passed away in 1980.

Safiyya/Safia/Sophie Tharwat, who plays the female lead in Rihlah ela el-Qamar, only appeared in a handful of films, but was famous in Egypt because of her contribution to female sports, in particular synchronised swimming. During the 50s she became one of the country’s top swimmers, and won a national tennis championship. In the 60s, she worked as a swimming coach and as an ambassador for synchronised swimming, eventually lifting Egypt into the international elite in the sport. In film, Tharwat’s only leading role was that of Stella in Rihlah ela el-Qamar, but she is probably best remembered for playing Faten Hamama’s daughter in Ezz El-Dine Zulficar’s successful Among the Ruins (1959). She also had a small role in Chahine’s classic Cairo Station (1958).

Edmond Tuima, sometimes as Tuema, was likewise an interesting character. Born to Lebanese parents in Cairo, Tuima attended French schools in the early 20th century, which so affected his language that he spoke and wrote French better that Arabic, and spoke Arabic with a French accent. From an early age he was interested in acting, and was quickly typecast in the roles of foreigners on stage, which carried on into film in the 1930s. But rather than his acting, his most important contribution to Egyptian theatre and film was his broad cultural learning, his vast library and his mission to bring international plays and books into the Arabic stage and movie theatres. He would often travel to Paris to see the latest plays, and returned to Cairo with his suitcase full of scripts, which he translated from French. Tuima was also the go-to guy when anyone was adapting a foreign book into a film. His bread and butter, though, often came from his work giving private lessons in French.

Janne Wass

Rihlah ela el-Qamar. 1959, Egypt. Directed & written by Hamada Abdel Wahab. Starring: Ismail Yassin, Rushdy Abaza, Edmond Tuima, Safiyya Tharwat, Ibrahim Younis, Ahmad Amer, Souad Tharwat, Hasan Ismail. Cinematography: Fouad Abdel Malek. Editor: Hasan Helmy. Art director: Hasan Polisois. Sound engineer: Nasry Abel Nour. Makeup: Mitcho. Produced by Hamada Abdel Wahab for Delta Films

Leave a comment