The Philippines was a major producer of sci-fi movies in the 50s, but few of the films have ever been seen by modern film scholars and fans, since most of them have been lost, and few have aired on TV. Here we take a look at the six first, lost, Pinoy SF movies.

This blog follows the history of science fiction movies in chronological order, one review/essay at a time. At this time of writing, I am reaching the end of the 50s, and have by now covered a multitude of films, primarily European and American. By the 1950s, the number of countries that had actually produced science fiction movies – even in their broadest sense – was perhaps surprisingly low. The 50s, generally considered the first Golden Age of science fiction movies, was dominated by Hollywood, with Europe, which led the way in the silent era, surprisingly passive on the SF front. The UK produced around a dozen or two science fiction films (plus a number of TV shows) in the 50s, and Japan exploded onto the market with its kaiju and space invasion films in the second half of the decade. Mexico was another strong player, even if the majority of its science fiction output was of the comedic variety.

When it comes to the rest of the world, science fiction movie production was patchy at best in the 1950s. On Scifist I have covered only a handful of science fiction movies made in the 50s that were not produced in the above-mentioned countries. A couple from the Nordics, a couple from France, a handful from Russia, a handful from Argentina and Brazil, two films from India, two from Egypt and one from Turkey. And that’s pretty much it.

One country I have not covered is the Philippines – which produced a whopping 6 or even 7 sci-fi movies in the 50s, depending on how you count. That is because almost all of these films are considered lost or at least extremely rare and not available for screenings, let alone home viewing. The films in question are: Taong Putik (1956), Exzur (1956), Tokyo 1960 (1957), Zarex (1958), Tuko sa Madre Kakaw (1959, Anak ng Kidlat (1959) and Terror is a Man (1959). Sometimes lumped in with these is Kahariang Bato (1956), but that’s only because it was re-edited into the US patchwork movie Horror of the Blood Monsters (1970), which contains sci-fi elements. The original film is better described as a caveman action melodrama.

Because all of these – except Terror is a Man – are all lost films, rather little is known about their plots, with a few exceptions, however, they all roughly fall into two categories: alien movies and monster movies, with an emphasis on the latter.

I’ll go over each of these films in detail further down, but before we get there, a short summary of the history of “Pinoy” cinema is perhaps suitable in order to lay the scene. The Philippines, a group of islands situated east of Vietnam and north of Indonesia, has a long and interesting history as a collection of small kingoms and fiefdoms, and extensive trading with continental Asia and the islands of the Pacific. It was colonised by the Spaniards in the 17th century – they brought with them Christianity, European education (the Philippines have Asia’s oldest European-style university), European culture and oppression. In 1898 the islands became part of the United States, and were then briefly occupied by Japan during WWII, before gaining independence in 1946.

As a result of its colonial history, the Philippine or Pinoy culture is a curious blend of indigenous culture, Spanish, US American and to some extent Japanese. The history of cinema in the Philippines is long – the first movie screening took place at the end of the Spanish rule in 1897, just a year after the Lumière brothers had held the first ever screening in Paris. When the Americans took over the Philippines a few years later, they quickly discovered the usefulness of film for propaganda purposes, both with the Filipino people as the target audience, and for justifying the American rule over the islands in the US and internationally, which led to strong investments in the cinema infrastructure and the Filipino movie industry.

US and European film distributors set up local offices in the capital Manila, and after WWI Hollywood films dominated the cinemas. In the beginning, most filmmakers were wealthy foreigners, but the first feature film made by Filipinos was released in 1919. The film industry in the Philippines really started growing in the 30s, but was interrupted by WWII and the Japanese occupation. Because the Philippines had much better studio facilities than Japan, the occupational forces used the Philippine studios to produce many of their propaganda films and newsreels, and cinemas were flooded with Japanese movies.

After the war, the Philippines gained their independence, and the movie industry really took off, starting what became known as the first Golden Age of Filipino cinema in the 50s. The decade was dominated by the Big Four – four major studios that would churn out as many as 350 movies a year, making the Philippines the second most prolific movie producer in Asia, after Japan. During the decade, the movie industry became highly professionalised and filmmakers greatly improved their technology, artistry and storytelling. Prestige films of genuine artistic quality were produced during this era, and it saw the emergence of such directors as Gerardo de Leon, Manuel Conde and Eddie Romero. Naturally, Filipino movie stars also took the scene, like Gloria Romero, Tessie Agana, Fernando Poe and Jesus “Og” Ramos. Samuel Conde’s Genghis Khan (1950) was the first Asian film to be screened at the Venice film festival, and other notable films were Leon’s Ifuago (1954), a drama depicting the lives of the titular mountain tribe, Lamberto Vera Avellana’s Kandelarong Pilak (1954) and Anak Dalita (1956), the first Asian film to get a screening at the Cannes Film Festival, as well as social realistic Malvarosa (1958). The Pinoy film industry started to decline in the 60s, when the monopoly of the Big Four was broken up, which, among other things, led to an upsurge in genre movies and soft porn, but that’s for another post.

However, it wasn’t just high-falutin’ drama that was made in the Philippines in the 50s. Action and adventure films were popular, as were films based on mythology and folklore. The 50s also saw the emergence of the Filipino horror and science fiction movies, crime films and even a handful of westerns.

There is no one person or studio in particular that can be credited for the birth of Filipino science fiction movies, but a handful of names stand out. Two of the first SF films of the country, Exzur (1956) and Tokyo 1960 (1957) were produced by People’s Pictures and directed by Teodorico Santos. Zarex (1958) and Tuko sa Madre Kakaw (“Gecko on the Madre sa Cacao Tree”, 1959) were directed by Richard Abelardo, written by Clodualdo del Mundo Sr, and produced for LVN Pictures. And of course, one must give a mention to Eddie Romero, who co-produced and co-directed the Island of Dr. Moreau adaptation Terror is a Man (1959) – his first of many horror films to come.

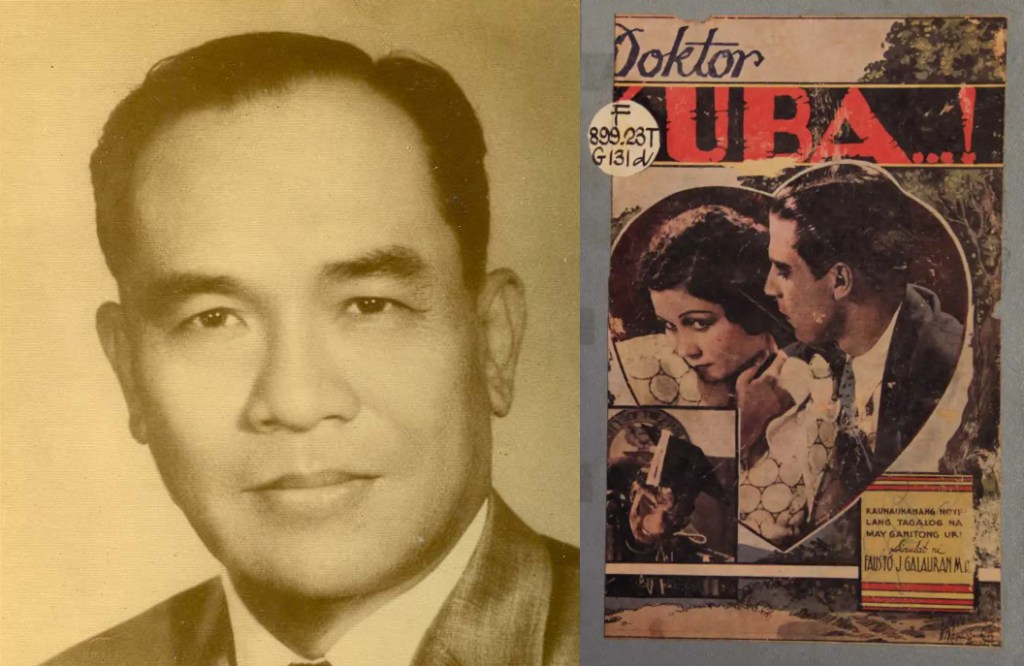

Literary science fiction and science fiction movies developed in an intertwined symbiosis in the Philippines in the 1950s. A small handful of literary precedents existed. SF enthusiast, author and scholar Victor Fernando Ocampo, the definitive autority on Philippine science fiction, states that The Philippines has the longest history of literaty speculative fiction in Southeast Asia thanks to early works such as Fausto J. Galauran’s novel Doktor Kuba and Mateo Cruz Cornelio’s novella Doktor Satan – both in the mad scientist genre, and both inspired by Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, even though the first would perhaps be better described as falling into the subgenre of “glandulal horror”.

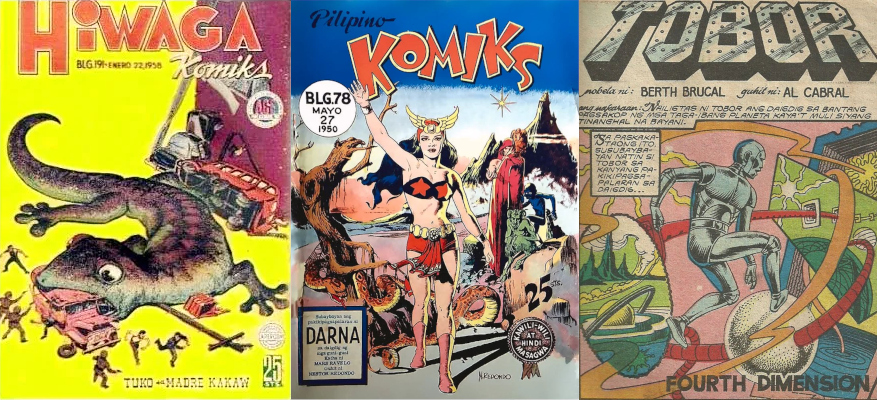

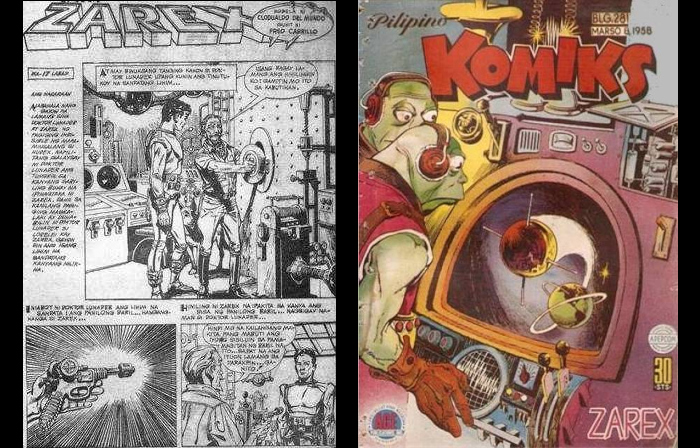

However, the driving force behind the development of science fiction in the 50s were comics and movies. Ocampo gives special mention to writers Nemesio E. Caravana and the afore-mentioned Clodualdo del Mundo. Caravana serialised the movie Exzur for Liwayway magazine, one of the leading publication for science fiction of the era, and in 1959 he wrote the SF novel Ang Puso ni Matilde (“The Heart of Matilda”), another variation in the shape-shifting trope, this time caused by a heart transplant. del Mundo, on the other hand, wrote the comic on which the movie Tuko sa Madre Kakaw is based in 1959, as well as the script for said film and for the movie Zarex.

Now to the movies themselves. The information below is cobbled together from information I have gleaned from a number of different sources, but special mention should go to Victor Ocampo and Simon Santos at the blog Video48. Some of the images used here are taken from Santos’ blog. I have e-mailed him and asked for permission to use them, without getting a reply, so I hope he won’t mind me posting them here.

Taong Putik (1956)

A Golem-inspired tale of a Mud Man rising from the swamp to take revenge on those who have buried him unchristined as an infant.

Taong Putik, or “Mud Man”, seems to have been borderline science fiction, even if it is often lumped together with the atomic monsters of the era. The film seems to have been shown on TV during the 60s and 70s. The most substantial plot synopsis I have found actually comes from Jose Manuel A. Santos’ novel Not Forever But Always, in which a character remembers seeing the movie on television. As described in the book, Taong Putik revolves around an infant who dies at birth, and is buried in a pool of mud, unchristened, and comes back to haunt the village in the form of a monstrous mud man. As such, this is more of a fantasy ghost story, with elements borrowed from the old Jewish folklore of the Golem. However, since other sources claim, albeit with little conviction, that radiation is somehow involved, I’m keeping the film on the list.

The movie was produced by the studio Everlasting. A story treatment was done by prolific screenwriter and sometimes director Johnny Pangilian and likewise writer/director Manuel Songco. Both were at the very beginning of their careers and neither of them seem to have had anything to do with science fiction later. Pangalian did direct two cheap Wonder Woman-type superhero films, but from the clips I have seen they seem to play more like fantasy. Screenplay and directorial duties are handles by Artemio B. Tecson, a writer/director who seems to have had a fairly short but, from what I can tell, reasonably successful career, working with many top stars of the industry, such as Gloria Romero and Alicia Vergel.

Speaking of Vergel, she is also first-billed in Taong Putik, although I have found no character information. At the time of filming, Vergel was had already won multiple awards for her work in the 50s, and was particularly well known as an action star who “did her own stunts”. Likewise award-winning actors Amado Cortez and Ruben Rustia are second- and third-billed.

Taong Putik. 1956, Philippines. Directed by Artemio B. Tecson. Written by Johnny Pangilian, Manuel Songco, Artemio B. Tecson. Starring: Alicia Vergel, Amado Cortez, Ruben Rustia. Produced by B.F. Ongpauco for Everlasting Pictures.

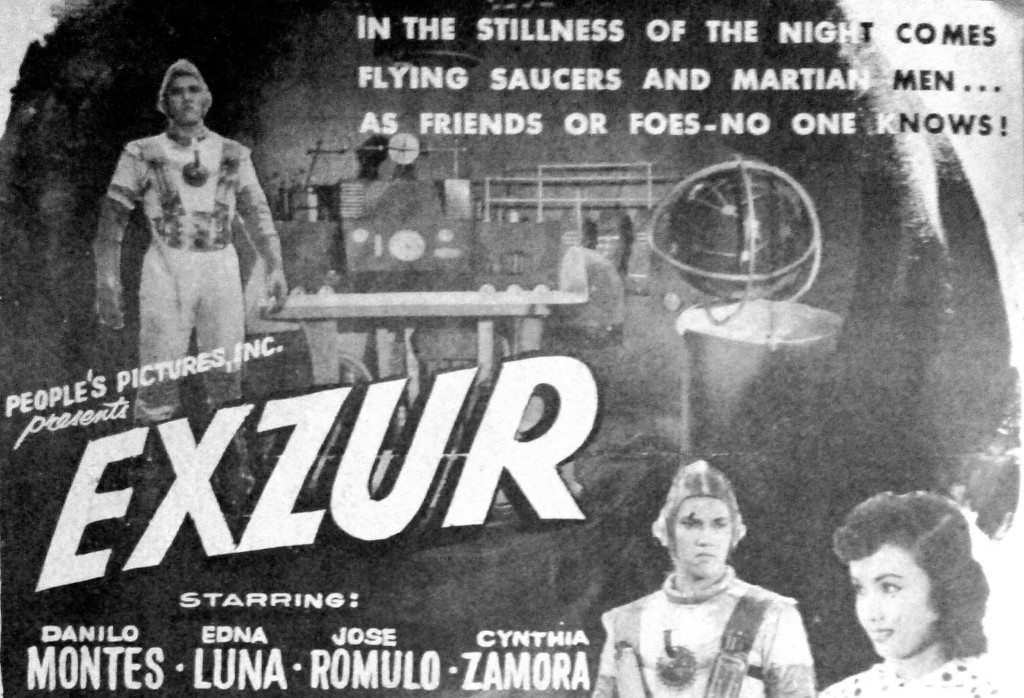

Exzur (1956)

Flying saucers invade the Philippines in this movie, but some of them might actually be benevolent, as the picture seems to have been heavily influenced by The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Next up, also in 1956, was the alien invasion movie Exzur, written both for the screen and for the comic serialisation by Nemesio E. Caravana, and diected by Teodorico C. Santos. Every plot synopsis I have read feature nothing but the same blurb from film scholar Victor Ocampo, stating that the film “featured the dramatic destruction of Manila’s City Hall, the Bureau of Posts building and Quezon Bridge by an armada of flying saucers”.

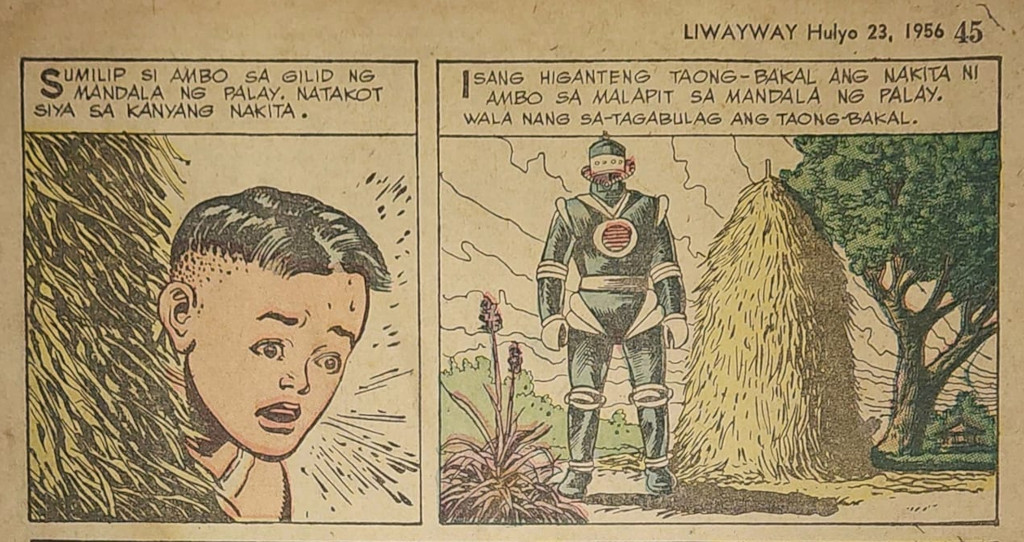

However, according to the few pages from the comic I have been able to find and translate, it actually seems to be based primarily on the 1951 Hollywood movie The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review). It does indeed seem to feature an armada of flying saucers invading the Philippines, but the main character, an alien by the name of Exzur, is portrayed as a benevolent visitor. The pages I have seen have him interact with a young boy, who seems to become something of an ally. The comics feauture an “iron giant” that at one point stands motionless in a field, very much reminiscent of Gort in The Day the Earth Stood Still. We see Exzur exiting the iron giant from a hatch in the robot’s back suggesting that Exzur uses it as someting akin to a vehicle. Taglines on the posters say: “Exzurians invade the Philippines!” and “Did he come in peace … or to conquer?” It would be interesting to see how all of the special effects were pulled off on screen, but unfortunately I have found no stills from the movie, other than the poster, which tells us very little.

Screenplay here is by the above-mentioned Nemesio E. Caravana, one of the Philippines’ science fiction pioneers – apart from the story of Exzur he is also responsible for the country’s third science fiction novel – Ang Puso ni Matilde – in which a girl gets a heart transplant from a bulldog and apparently starts taking on the characteristics of the dog. Caravana was active as a director, screenwriter and occasionally as an actor between the late 40s and the mid-60s. Direction is handled by Teodorico C. Santos, likewise both a screenwriter and director. He was nominated for the Filipino FAMAS award four times, twice for best screenplay, and twice for best director. He won the award for best screenplay for the romantic drama Habang buhay (1953).

The studio, People’s Pictures, did a bit of a publicity stunt with the casting of the film: apparently they “held a competion” for the role of Exzur, and the winner turned out to be bodybuilder and former “Mr Philippines” Jose Velez. Velez doesn’t seem to have appeared in any other movies, according to his IMDb credits. The film also featured a star-studded cast including Danilo Montes and Cynthia Zamora, who were both FAMAS nominated for best actor/actress twice.

Tokyo 1960 (1957)

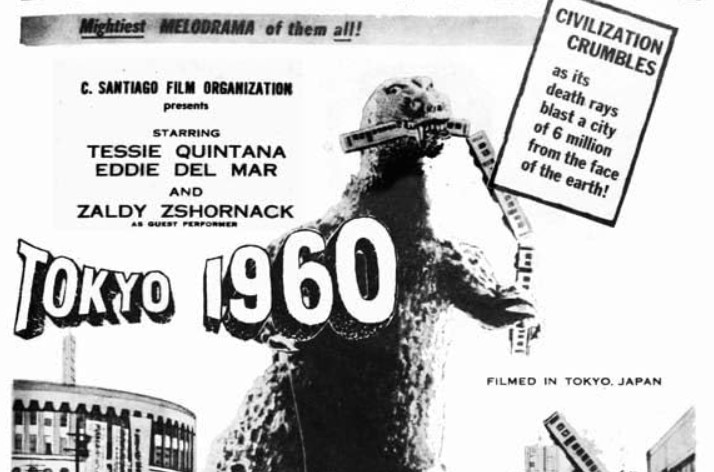

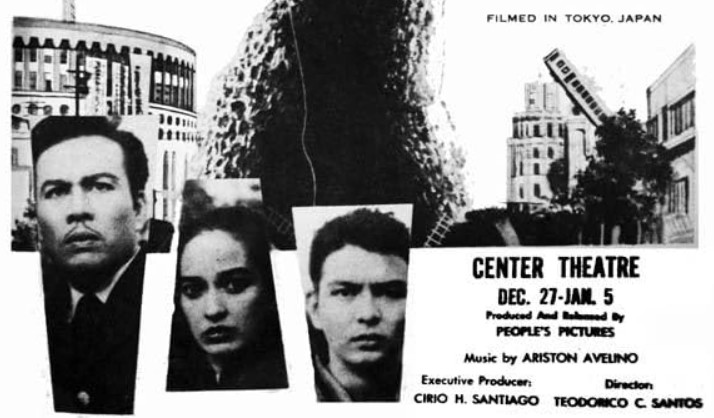

A cut-and-paste movie inserting a new plot with Filipino actors into the original Godzilla film, very little is known about this production.

This one resurfaced resently, thanks to Simon Santos at Video48. Seemingly all that remains of this film are two posters/ads, and kaiju and science fiction fans have tried desperately to dig up more information in the picture, with pretty much no luck. What seems clear just from looking at the ads is that this is some kind of reworking of Gojira (1954, review), since the monster depicted is the one from the original Godzilla movie. Furthermore, since the posters list Theodorico C. Santos as the director and features Filipino film stars as “starring”, this is not just a dubbed version of Gojira, but a film that contains new footage.

Robert J. Kiss at Classic Horror Film Board has done a nice summary, where he concludes that the picture actually depicts artwork from the American re-edit Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956, review) and not the original Gojira, which means that it is highly likely that this is a re-edit of the US movie and not the Japanese original. One can perhaps make the conclusion that Tokyo 1960 is Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, with all the American footage excised and replaced with a new Philipine story. What this story entails is anyone’s guess, though.

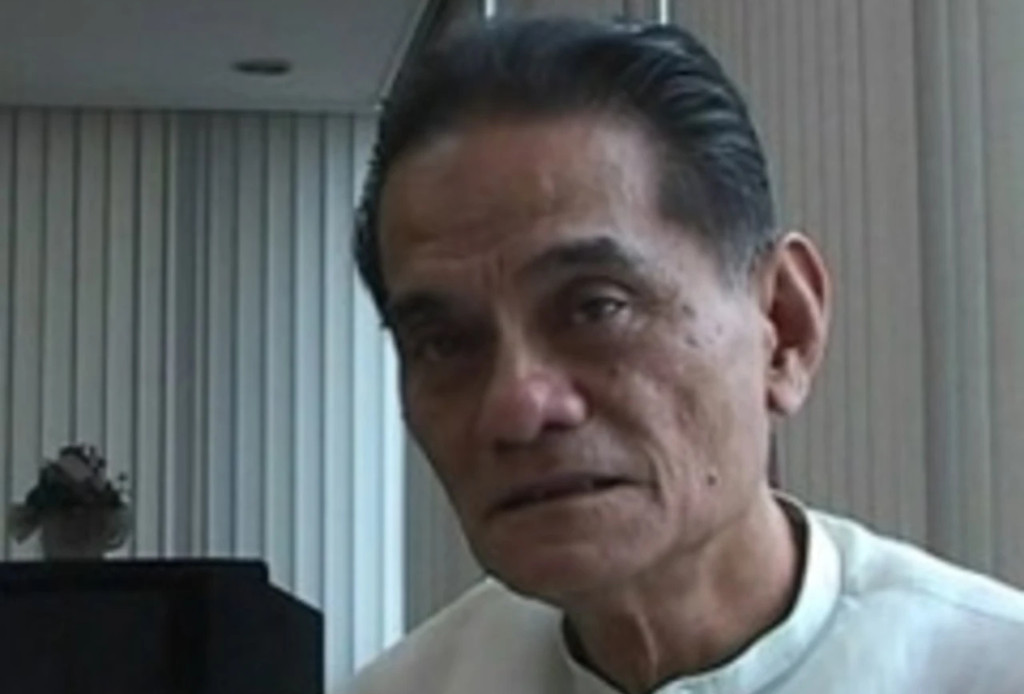

Tokyo 1960 was produced by Cirio H. Santiago, the son of the founder of Premiere Pictures. Santiago is something of a cult movie legend, having collaborated with people like Roger Corman, Jonathan Demme and Joe Dante. Santiago directed and/or produced numerous films primarily aimed at the US market through his distribution deal with Corman’s New World Pictures. When Corman started to basically produce by proxy many of his B-movies in the Philippines, Santiago was the man who took over production duties. He pioneered the “women in prison” films of the early seventies and both produced and the directed the blaxploitation film TNT Jackson (1974). Among his handiwork are also such cult favourites as Vampire Hookers (1978), Up from the Depths (1979) and Firecracker (1981). In the 80s and 90s he became known for a slew of movies set during the Vietnam war, making him something of “Namsploitation” royalty. Santiago also produced and/or directed a number of science fiction movies, many of them in a post-apocalyptic setting. These include, but are not limited to: Up from the Depths, Stryker (1983), Wheels of Fire (1985), Equalizer 2000 (1987), The Sisterhood (1988), Dune Warriors (1991) and Robo Warriors (1996). Despite devoting most of his career to cheap B-movies, Santiago was a hugely respected man in the Filipino film business, and directors like Steven Spielberg and Quentin Tarantino are among his fans. The website Exploding Helicopter has counted that Cirio H. Santiago has directed more films featuring an exploding helicopter than any other director – 15 of them.

Zarex (1958)

Another film about which we know rather little, this one features Filiponos landing on the moon, where they find a civilization of Lunarians.

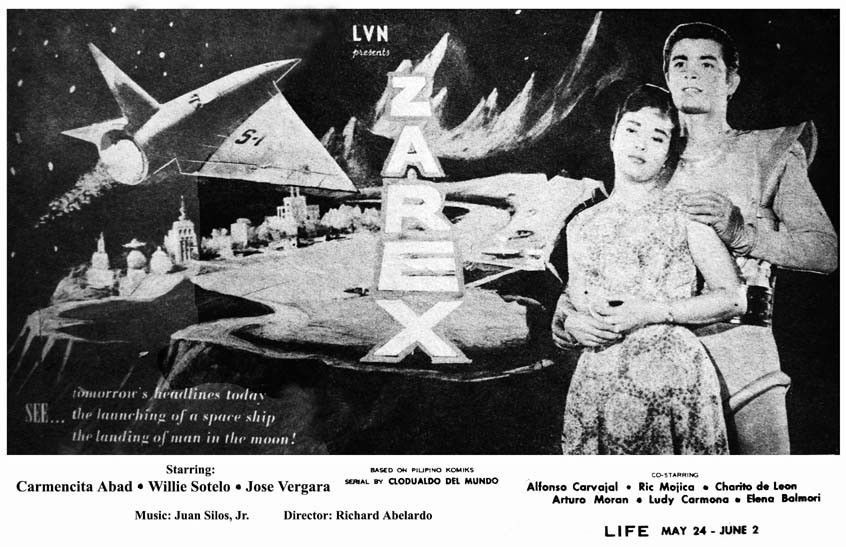

The first Philippine space movie, Zarex, was penned by science fiction pioneer Clodualdo del Mundo Sr. and directed by Richard Abelardo, perhaps the most outstanding special effects director in the country in the 50s. This is yet another film that we know little of. It is sometimes described as a Filipino take om Destination Moon (1950, review), but I suspect that the only reason for this is that Simon Santos at Video48 namedrops that movie in his post about Zarex simply to illustrate the Hollywood trend of moon landing films. As far as I can tell, there’s nothing that points to any real similarites between the two films.

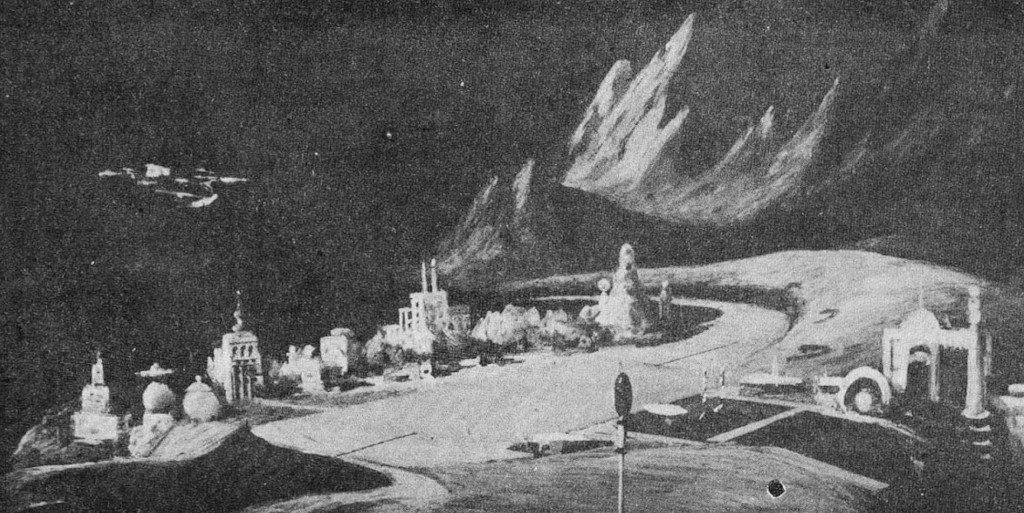

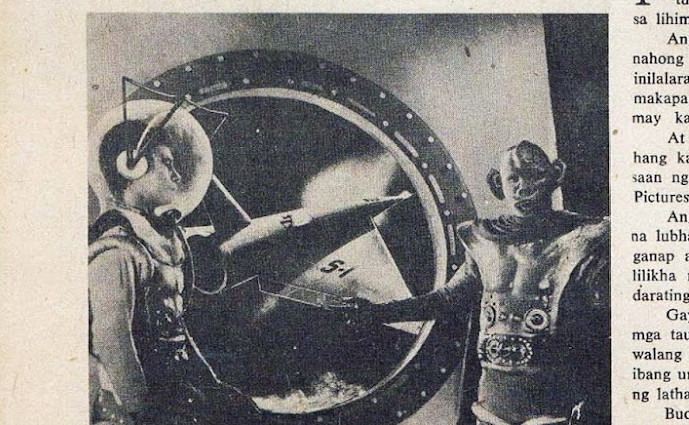

The best information I can find about the film comes from a cutout from an old Filipino film magazine called Literary SONG MOVIE Magazine, that has been provided by the Pelikula, Atpb blog. The spread is clearly a promotional ad for Zarex. I ran the cutout through Google Translate, which didn’t really get me a lot of information, as most of the text is basically placeholder text speaking of the wonder of travelling to other worlds. It’s clearly a promotional article written by the magazine based on the images provided by the studio and a brief advertisement blurb. However, there is a line which says that the film is about a crew on a spaceship that travels to another planet inhabited by other types of creatures. The text is accompanied by a photo of lead actor Willie Sotelo in a space suit standing by a window of a spaceship looking out at another spaceship, with the edges of mountains seen at the bottom of the window. On the other side of the window stands a humanoid creature with a decidedly alien-looking head. Other pictures show Sotelo standing in a field with a spaceship behind him, and what looks like concept art for an alien city. However, there is also available a magazine ad that clearly states that this is a film about a moon landing, and not about travelling to another planet. Thus, this is a film about Filipino astronauts encountering aliens on the moon. This helps us at least place the film in a setting, but says little about the actual plot.

The movie was also turned into a comic in the country’s leading comic magazine Komiks by writer Mark Ravelo. Komiks and the movie industry had a symbiotic relationship, with komiks often being turned into films, and vice versa. The cover of the Zarex issue has two green-skinned aliens looking at a screen on whuch they appear to be seeing some satellite-looking device leaping past a planet. In one comment on a collector blog vaguely remember reading the comic, and says that it actually featured an alien character called Zarex that returned to Earth with the astronauts, and that large parts of the comic was about Zarex on Earth. Whether the commenter’s recollection is correct, or if any of this is featured in the film is impossible to say.

Zarex was produced by LVN Pictures and was directed by Richard Abelardo, the Philippine’s number one special effects man. Simon Santos writes that Abelardo set off for Hollywood as a young man in the early 30s, committed to creating a career in America. Here he worked in some capacity on films like the James Cagney vehicle Footlite Parade (1933) and Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). However, ailing parents brought him back to Manila in 1936. Here his Hollywood know-how and artistic inclinations quickly made him a popular go-to guy for films that required special effects. Among other things, he introduced the camera crain and rear projection to Filipino cinema. He made his directorial debut in 1945 and helmed many historical, biblical and fantasy films. A princess turning into a stone in Ibong Adarna (1941), a floating castle in Prinsesa Basahan (1949) and Moses parting the Red Sea in Tungkod ni Moises (1952) are some of the effects he is remebered for. Plus, of course his two science fiction movies, Zarex (1958) and Tuko sa Madre Kakaw (1959). Lead Willie Sotelo also played the home-grown superhero Captain Barbell in the 1965 movie Captain Barbell kontra Captain Bakal.

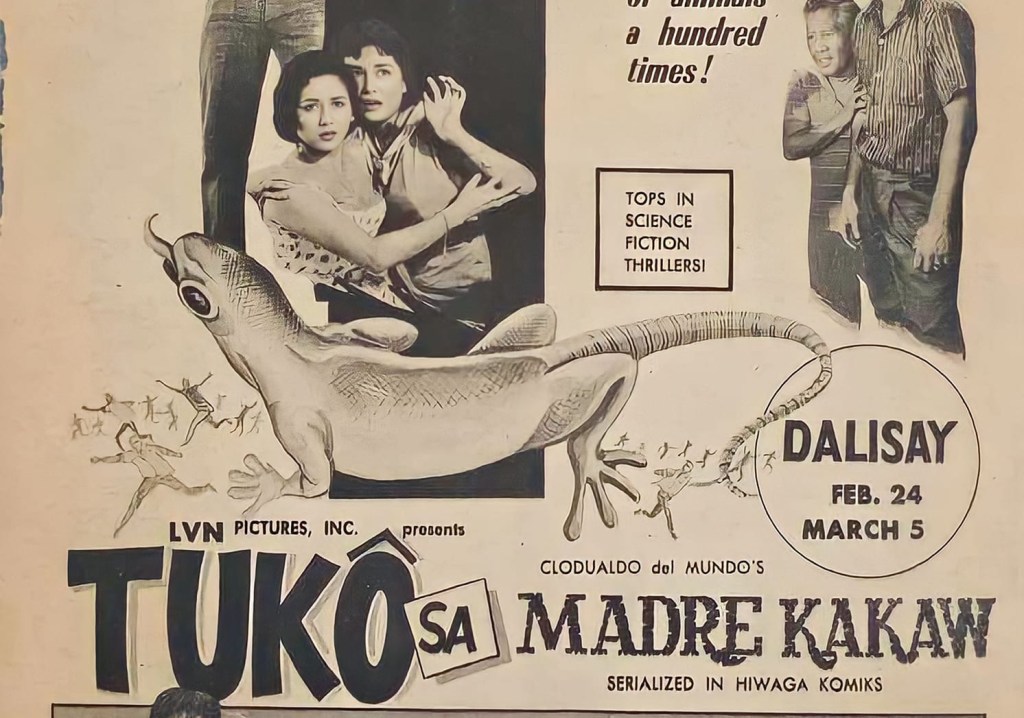

Tuko sa Madre Kakaw (1959)

This one we have a full plot synopsis for. Based on a comic, it is the classic tale of a mad scientist creating a monster. In this case a biologist who makes a giant gecko, which terrorizes the neighbourhood.

Which brings us to Abelardo’s other science fiction film, Tuko sa Madre Kakaw, or “Gecko in the Madre sa Cacao Tree”. We know more about this movie, since it seems to have been shown regularly on TV in the late 70s, and thus we can find a few plot synopses by people who have actually seen it. A few stills also survive.

A detailed synopsis has been posted by the anonymous creator at Melcore’s CinePlex Blog. In a nutshell, this is a very classic “mad scientist creates giant monster” movie. A mad biologist (Vic Diaz) invents a serum which makes animals grow large, and tests it on a gecko (the “tuko” of the title) which lives in his family’s madre de cacao tree (the “Madre Kakaw” of the title). The gecko grows, first to the size of a man, and then to huge proportions, and starts terrorising the neighbourhood. Meanwhile, the mad scientist is sought out by another scientist (Caridad Sanchez), who has been hired by the Americans to steal the mad scientist’s formula.

The mad scientist’s assistant and servant Obligacion, however, abandons his master after he learns that he is plotting world domination, and teams up with a few other characters (a hero role is apparently played by, once again, Willie Sotelo), who plot to stop the madman. The military is called in, but no weapon can harm the giant lizard. That is when Sotelo’s character remembers an apparatus he has seen in the madman’s lab, which may be able to destroy the creature. Upon arriving to the lab, they find the foreign-hired Sanchez, who has tried to steal the formula but is trapped in the lab, to which the giant gecko has returned. Rescuing the apparatus from the burning lab, the find it to be some sort of ray cannon, which they shoot the lizard with, making it return to normal size – but not before it has killed the foreign interlopers.

There’s also an “origin story” for the mad scientist, following from his childhood. Apparently the biologist is a misunderstood genius whose raging against the world after having been spurned in love, and tried to commit suicide by pouring some concoction over his head – resulting only in him going bald (and perhaps mad).

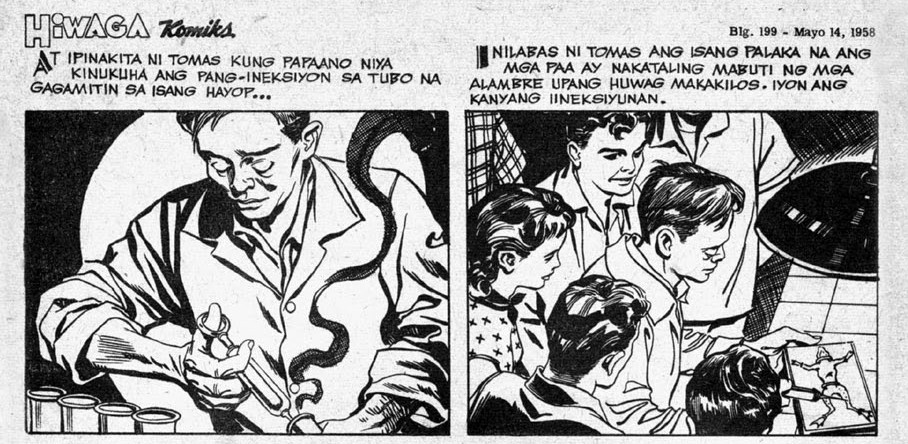

The script for the Tuko sa Madre Kakaw was adapted from a 1958 comic by Clodualdo del Mundo Sr, published in Hiwaga Komiks. As far as I can tell, the film follows the komik rather faithfully. Sci-fi scholar Victor Ocampo describes the story as one of the best science fiction and komiks entry of the era. The plot, as far as I can tell, is rather derivative of other pulp and Hollywood stories of the era, but does incorporate elements of Philippine folklore and myth – such as the gecko’s ominous cries as a herald of bad omens.

Like Zarex, Tuko sa Madre Kakaw was directed by special effects wizard Richard Abelardo. In the few surviving stills from the film we can see the giant gecko played by a man in a suit, walking upright. The suit seems quite accomplished, but without seeing it in motion it is difficult to ascertain how effective it was on-screen.

Lead actor Vic Diaz is described in his IMDb bio thus: “Vic Diaz reigns supreme as the jolly evil fat man of Filipino exploitation cinema. With his broad, mirthful grin, beady dark brown eyes, trim black goatee and mustache, swarthy complexion, thinning hair, protuberant sagging belly, and smooth, oily baritone voice, Diaz was a steady, scuzzy, often sinister and always charismatic presence in an alarmingly large volume of horror films and delectably down’n’dirty 1970s drive-in features alike. He has been often described as the Filipino equivalent to Peter Lorre. “Diaz was a favourite of Eddie Romero and Cirio H. Santiago.

A former baseball player, handsome Willie Sotelo was a popular heartthrob in Filipino movies in the late 50s and 60s, but seems to have dropped out of acting in 1967. Caridad Sanchez, playing the rival scientist in the movie, is a very respected character actress, best known for her work in soap operas. In 1999 she won a lifetime Star Award for her work in television. But through her career she was also a highly sought-after character actress in movies, and won two FAMAS and two FAP awards for best supporting actress. She retired from acting in 2015.

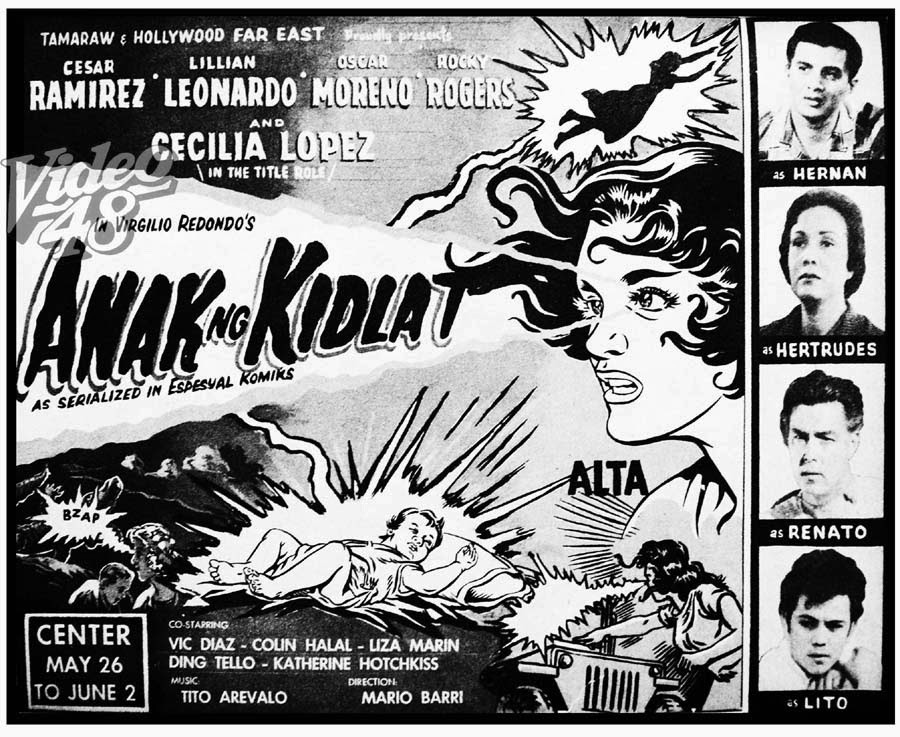

Anak ng kidlat (1959)

An example of the homegrown superhero genre, which became very popular in the Philippines, this film seems to follow the romantic and crime-fighting exploits of a young woman whose father is lightning.

Like Taong Putik, this one is borderline science fiction. Like a lot of other Filipino movies, this 1959 production is based on a komik, this one written by Virgilio Redondo, and it is a superhero story – a genre that was very popular in the Philippines, and often featured home-grown protagonists, many of them female. Such is also the case here. Both the movie and the komiks is titled Anak ng kidlat, which translates as “Child of Lightning” and features a girl who is born through a sort of immaculate conception. Her mother was struck by lightning, and her father is literally lightning.

From uploaded komiks pages, at least the comic seems to be focused, partly on the main character, Alta’s, romantic endeavours, and her journey to come to terms with who and what she is. One strip sees her reconnect with her love interest Hernan on a boat, on which she lands – apparently her command over electricity gives her a number of superpowers, such as the ability to fly. In the strip, she tells Hernan about her origins and her nature, and asks if he can accept her for what she is, despite not being human in the strictest sense. Hernan has no qualms over her origins, and they kiss and set off to be married. Other plot synopses describes her battling forces of evil, while also being accused of being dangerous and an abomination. Unfortunately, I have not been able to dig up more on the plot.

The film was produced by Tamaraw-Hollywood Far East Productions and directed by Mario Barri, a somewhat anonymous actor and director who was active during the 50s and 60s. The title role of Alta was played by Cecila Lopez (real name Mary Helen Wessner), who appears to have been a minor star of the Filipino movie scene in the 50s and 60s, and won a FAMAS award for best actress in 1952. She continued acting into the 80s. Her love interest and the male lead Hernan was played by Cesar Ramires, a prolific leading man between 1950 and 1977, who was nominated for two best actor FAMAS’s. Vic Diaz, who played the lead in Tuko sa Madre Kakaw, is also featured in the cast list, presumably as a villainoius character.

Conclusion

That’s that for the lost Pinoy science fiction films of the 50s. The next science fiction movie produced in the Philippines – and the earliest one that is preserved – was the Island of Dr. Moreau adaptation Terror is a Man (1959), directed by Gerardo de Leon and Eddie Romero, and co-produced by Romero and Kane W. Lynn. This was one of the first Filipino films to bring in Hollywood stars in order to boost it’s international interest. This became a common practice from the 60s onward, when the same people, Lynn and Romero, along with actor John Ashley, founded Hemisphere Pictures and started producing horror movies for an international audience. This led to a collaboration with Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, and the rest is history.

As for the six lost science fiction movies, one naturally asks why they are all lost. The answer doesn’t seem to be one single factor, but a combination of several ones. One reason seems to be that preserving these kind of low-budget genre movies wasn’t a priority. However, some of them must have been archived at least for some time, as we have evidence of them having been on TV in the 70s. The main factor that seems to be cited is poor archiving. According to film scholar Bliss Cua Lim, the Philippines has been notoriously bad at preserving its cinematic history, mostly due to a lack of a coherent national archival policy. No national film archive even existed prior to 1981, and after that efforts to preserve film prints have been patchy at best. The first archive was closed down with the ovethrow of dictator Fernando Marcos in 1986, and different poorly funded projects tried to keep film history safe after that, some of them commercial, such as the ABS-CBN Film Archives. A national film archive was founded in 2011, and despite still running, it has reportedly been severely underfunded since the country’s last presidency under Rodrigo Duterte. Lack of proper facilities and resources has been especially problematic in a country like the Philippines, with a hot and humid climate which quickly starts to eat away on film stock. Another compounding factor was the collapse of the “Big Four” film studios in the 60s: when the studios scaled down or even closed shop altogether, many of their assets were spread on the wind, many of them ending up on garbage heaps.

As for the films produced in the 50s, it is hard to make an assessment of them, as so little remains in the way of documentation – in some cases, a poster is all we have to go on. A lack of ambition doesn’t seem to have been an issue, as many of them involve creatures and circumstances that would have required elaborate sets and/ors special effects. One point of reference might be Anak ng bulkan (1959), another very borderline science fiction movie – more in the realm of fantasy, about a boy who befriends a giant bird which is hatched after the eruption of a volcano. Here we find ambitious special and visual effects which are not always executed quite to expectation. The film features a rather impressive full-scale puppet on which the protagonist rides high in the sky in the film’s most ambitious moments. However, the compositing is quite crude, leaving the resulting image often over-exposed and with thick matte lines. The film, clearly inspired by Rodan (1957, review), also features scenes depicting the flooding of Manila. Here, again, is some rather impressive miniature work combined with less impressive visual effects. The film also utilises a good deal of stock footage and several re-uses of both stock footage and effects, telling that the resources haven’t quite matched the vision of the filmmakers.

As for the plots, as far as we can gather, they seem, at least superficially, to follow the tropes established by both Hollywood and Japanese science fiction cinema, but what local colour they might have brought to the table is hard to tell from the scarce information available. My interpretation is that there seems to be some influence from local folklore and fairy-tales, and a slightly more pronounced emphasis on melodrama than in corresponding Hollywood tales, but this is pretty much conjecture on my part.

As for the question whether any of these movies might ever resurface, film enthusiast online are not holding their breath. Had these films had international releases, there might have been a chance that copies may have survived in foreign archives or collections. Given the poor history of film archiving in the Philippines, however, it is not likely that any of them have survived.

Janne Wass

Leave a comment