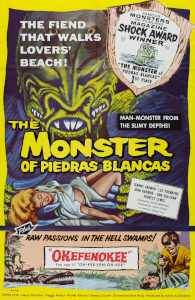

Bodies start piling up at the small town of Piedras Blancas when the lighthouse keeper neglects to feed the local gill-man hiding in the caves. This silly but charming 1959 independent production is a love letter to the monster movies of old. 4/10

The Monster of Piedras Blancas. 1959, USA. Directed by Irvin Berwick. Written by H. Haile Chase. Starring: Les Tremayne, Forrest Lewis, Jeanne Carmen, Don Sullivan, John Harmon. Produced by Jack Kevan.

Strange deaths are occurring at the Californian small town of Piedras Blancas. Along the rocky beaches, guarded by a lighthouse, people are getting mysteriously decapitated and drained of blood. Somehow it seems connected to irate lighthouse keeper Sturges (John Harmon) not getting his usual leftover meat scraps from storekeeper Kochek (Frank Arvidson). Talkative Kochek keeps telling everyone that it is a legend come to life – the monster of Piedras Blancas. Constable Matson (Forrest Lewis) tells Kochek to can it and stop spreading panic among the villagers. Sturges seems to know something, and forbids his daughter Lucille (Jeanne Carmen) to go out to the beach at night. Other than that, he ain’t saying anything.

The monster of Piedras Blancas was one of those films I had heard about in passing, often as a reference to really bad 50s movies. A super-low-budget movie, it was produced in 1959 by Universal’s former monster makeup wizard Jack Kevan, and filmed entirely on location at two spots on the coast of California – but curiously enough, not in Piedras Blancas.

When a strange scale is found on one of the victims, the town’s local busybody Dr. Sam Jorgenson (Les Tremayne) springs into action. Not only is he the local physician, but also coroner, marine biologist, chemist and funeral officiate. He is also the closest we get to a protagonist in this film’s ensemble cast. He is aided by young marine biology student Fred (Don Sullivan) who also happens to be Lucille’s girlfriend.

Jorgenson and Sullivan keep dipping the scale in different solutions and staring at it through a microscope, while trying to figure out what might have killed the poor victims. Constable Matson keeps telling people that the deaths are all accidental – fishers who have been caught in the squalls and had their heads decapitated by the jagged rocks. He seems most worried about superstitious Kochek stirring up panic with his wild tales. Between romantic swims at the beach with Fred, Lucille tries to tend her relationship with her distant, irate father, lighthouse keeper Sturges, who sent her away to school in the city after her mother died. Sturges seems mostly worried about the fact that he didn’t get the usual meat scraps “for his dog” from Kochek. And about the fact that Lucille keeps taking nightly swims on her own, despite him expressively forbidding her.

And indeed, during one of her nightly swims, we see a clawed hand reaching out for her clothes on the beach.

Things soon escalate. Not only are people killed on the beach, but soon poor Kochek is also killed in his shop. Shortly thereafter a deputy guarding the bodies that keep piling up in Kochek’s freezer room also gets his head lopped off. This time there are witnesses who see a scaly humanoid monster walk out of the freezer with the deputy’s severed head in his hand. When attacked with a meat cleaver, the monster simply brushes it off and walks back to the beach. So, the legend of the monster of Piedras Blancas is true.

While the sheriff, Jorgenson, Sullivan and a small posse try to figure out how to catch and/or kill the monster, Sturges sets out to confront it himself near the forbidden caves. He is later found injured and taken back to his lighthouse, where he tells his daughter the truth. After her mother died, Sturges went spelunking in the caves, where he realised something was living. Pitying the poor creature, he kept feeding it over the years, finding in the caregiving act some sort of companionship, “a pet monster”, realising the creature was a lonely as he was. At the same time, he realised that the monster could be a theat to Lucille, and sent her off to boarding school. And now, when he did not get his usual meat scraps (“I would even have paid for them!”) from Kochek, the monster has began hunting for his own dinner. Remorseful, Sturges admits that he has put the whole town in danger.

Meanwhile, our posse have decided that the monster cannot be killed with guns, and set out to catch it with a net. However, the monster is faster and kidnaps Lucille from the lightghouse. Sturges saves her by throwing and empty oil can at the monster, who drops Lucille and comes at him. When he is battling the monster atop the lighthouse, the posse arrives with their net, and we get our showdown…

Background & Analysis

The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959) is one of those no-budget films from the late 50s that are looked upon today with certain amount fondness, despite its many shortcomings. Like the ouvre of Ed Wood, this is made with a passion and enthusiasm that was sorely lacking in many of the by-the-numbers monster movies churned out by studios in the late 50s and early 60s. Not that it is as amateurish as Ed Wood’s movies – this one was made by seasoned professionals.

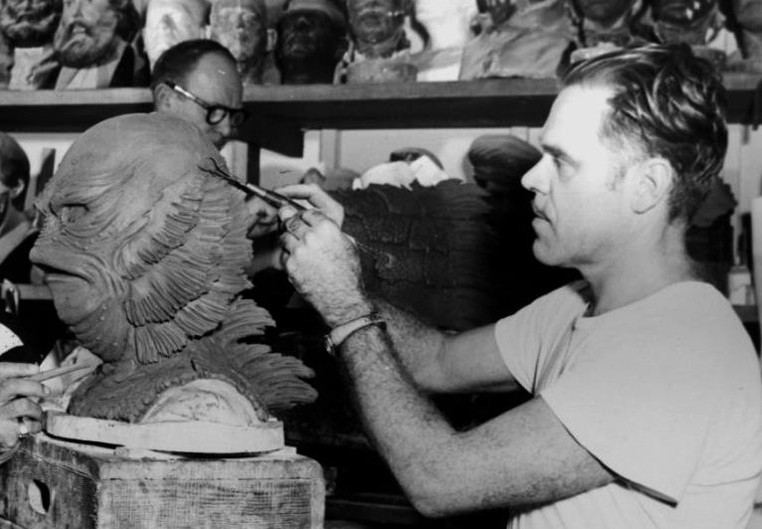

The movie traces its origins to Universal’s crisis in 1957, which led to mass firings at the studio. Two of the people laid off were dialogue coach Irvin Berwick and special makeup and suit creator Jack Kevan. Berwick had been a dialogue coach and dialogue director for many of the studio’s stars, and frequently worked with directors like William Castle and Jack Arnold. Kevan, on the other hand, had been a central cog in the machinery of Universal’s makeup department, working on several of the studio’s classic science fiction movies, creating aliens and monsters, like Gil-man from Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review). After they were laid off, the two friends got together to form their own production company, Vanwick Productions. Initially, the two planned to produce five movies for the company, but ultimately The Monster of Piedras Blancas was the only one they finished – although they did work together on a couple for films as writer-producer-directors in the early 60s.

To put the film into perspective, it was made at a time when drive-ins were still able to compete for the attention of teenagers with TV. Barring a short period in the early-to-mid-1950s, science fiction and monster movies were not something major studios in hollywood were prepared to put prestige money into, and with some very few exceptions, the majority of SF/monster movies between 1957 and 1967 had shooting schedules of 1-2 weeks and a budget of $100 000-$200 000. However, minor studio American International Pictures changed the way Hollywood producers, distributors and exhibitors looked at the productions of such movies. With an office of only a handful adminisitrators, no studio facilities of their own, and a ragtag team of freelancing writers, producers, directors, crew and actors, AIP were able to squeeze out a movie a week, often with a budget of under $100 000. As long as the film had monster on the poster, it usually sold enough tickets to turn a small profit. Producers, financers and distributors took note, and as a result there arose a small cottage industry of independent producers who started making science fiction and monster movies for not much more than pocket money.

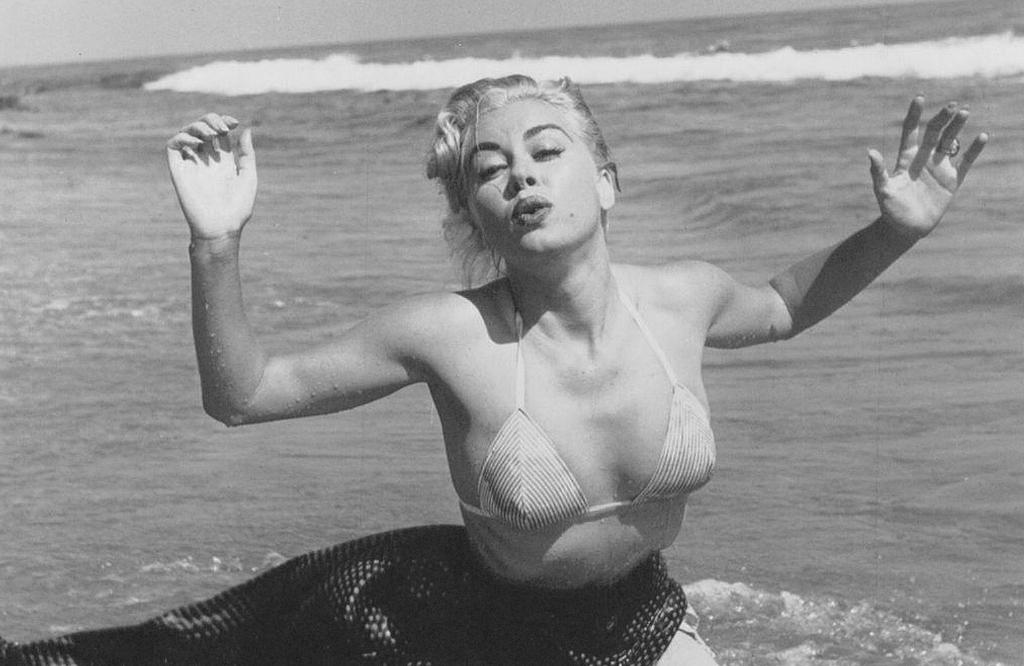

In the case of The Monster from Piedras Blancas, the budget was reportedly around $30 000, which was just about nothing even in those days. Almost all of the crew were old Universal hands who probably agreed to work for union minimum, and with Kevan and Berwick probably working double as producers, directors, makeup artists and production managers. The movie was cast with no-name actors, and the cast was billed in small print – the monster was the attraction. Jeanne Carmen was first-billed – less on the strength of her acting career and more on her notoriety as a pin-up model and her frequent sightings in tabloid papers accompanying people like Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley to various functions. Les Tremayne was second-billed, and probably the one name in the cast that anyone outside the most hardcore movie buffs would have been able to recognise. The rest of the cast was made up of background and bit-part actors who were probably friends of Kevan and Berwick, as well as townsfolk from the small town of Cayucos, where much of the film was shot on location.

For those not familiar with Californian geography, Piedras Blancas is a real place with a lighthouse. However, the film is not shot at Piedras Blancas, but at two different locations. For the lighthouse scenes, the lighthouse in Point Conception, about 100 miles north of Los Angeles, was used, possibly because the producers thought it was more picturesque. The rest of the film was filmed in the seaside town of Cayucos (a bit further north) and nearby Morro Bay. As far as I have been able to find out, no part of the movie was filmed in a studio, but used existing buildings in Cayucos. This lack of studio facilities and resources sometimes results in some amusing situations. For example, much of the action takes place in and in front of two facilities among the main road of Cayucos – one shop standing in as Kochek’s store, and a diner. Apparently, the film’s fictional Piedras Blancas has no sheriff’s office, and the investigators openly conduct all their business in front of the diner’s patrons. Also, apparently, the local lawman stores his guns behind the diner’s counter. Another amusing aspect is that the film crew only seems to have had access to a single car, which makes it seem as if the only car in all of Piedras Blancas is Fred’s jeep, which all the main characters must borrow or wait for.

As far as story and script goes, this is the kind of film that aims higher than the average program picture, and puts some thought into character development and personal drama. But when the drama is on the level of something a 12-year-old would have written, it doesn’t necessarily make for a particularly nuanced script. The premise of the movie is that Sturges, the lighthouse keeper, felt lonely after his wife died. But it makes little sense that the solution to his loneliness is to send away his only daughter in order to feed a creature in a cave that he never even sees. His revelation toward the end of the movie, when the monster has killed something like a dozen people, that the whole situation might perhaps be his fault, is a little feeble and a little late.

Of course, there is the case to be made, although the film doesn’t make it, that Sturges had little to do with the monster’s killing spree, as the logic makes no sense at all.

- Why did Sturges need to start feeding the monster in the first place? For all we know, it was doing great when he discovered it.

- The pivoting point of the movie seems to be the fact that Kochek doesn’t give Sturges the usual scrap of meat to feed the monster. But the killings start before Sturges visits Kochek’s shop, implying that it had been fed the day before, but started killing people nonetheless.

- Sturges says that he “would have paid” for the scraps if Kochek had only kept them. Well, why doesn’t he just buy some steak instead? The monster probably wouldn’t have minded a better cut once in a while.

- Why does the monster suddenly become vampiric? It’s been eating meat scraps for years – it apparently had no need to suck humans dry of blood during that time.

- While we’re at it: Why doesn’t the monster decapitate Lucille, but carries her off to his lair?

- Why doesn’t constable Matson call in reinforcements when half the town of Piedras Blancas has been killed?

- Why does constable Matson think that the safest place for Lucille will be the lighthouse, around which the monster has been prowling, rather than in town?

- Why do Fred and Jorgenson need to keep wasting time on examining scales left behind at the site of the killing in order to identify the killer, after they have just witnessed a sea monster walking out of a freezer holding the head of a man in its hand?

There are more questions, but you get the gist.

The main flaw of the movie, however, it is slowness. I don’t complain about the fact that we don’t see the monster in full until the film’s last 10 minutes – in fact, director Berwick is able to build up a modicum of suspense and anticipation by only showing bits and pieces of the monster for most of the picture’s running time. But he is counteracted by the script, that isn’t able to drum up any sense of urgency. Much of the movie consists of people solemnly discussing what to do about the monster – or even if there is a monster. When Dr. Jorgenson and Fred sit about their microscopes analysing scales while a monster is on the loose in their town, having just ripped the head from a victim, constable Matson is understandably frustrated. Jorgenson, in a lightly humorous tone, chides that “Our good constable doesn’t seem to realise that scientific investigation is a long and tedious process”. The viewers do understand this, but may not be convinced that the entire process needs to be displayed in a 70-minute monster movie. Throughout the movie, the small village seems to sort of go about its business, despite several brutal murders, and even when a sea monster carries off a severed head in the town’s main street, we’re met more with a feeling of indignation rather than terror.

Speaking of that scene, one thing that makes this movie stand out is that it is rather gory for the time. In particular the scenes featuring, and lingering on, the severed head are some of the strongest seen in a film of this kind up to this point. Off the top of my head, the only ones I can think of that would have carried the same sort of gore would be the scene in which Kevin McCarthy stabs the pod duplicates of himself and his co-stars in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review)

As low budget as this film is, it is professionally made and does look at least a bit more expensive than its $30 000 budget. The main reason for this is the monster itself. Jack Kevan seems to have had access to Universal’s workshop and to his old monster suits, despite having been laid off from the studio. The Monster’s head, torso, legs and arms seem to be originals made for the Monster of Piedras Blancas, and they are just as well made as anything Kevan did. The design for the head is, however, a bit illogical: there’s two flaps of skin connecting the upper and lower lips, making you question how the monster is able to bite and eat people. Overall the design – sans head, feet and hands – is reminiscent of the Gil-man, which by all accounts was deliberate. However, the creature’s clawed hands are borrowed from Kevan’s suits for the mole men in The Mole People (1956, review) and its insectiod feet were previously seen on the Metaluna Mutant in This Island Earth (1955, review).

Thematically, the film doesn’t seem to try to address any of the geopolitical tensions running high in the late 50s, nor any other broader theme in particular. It sets out to put the characters at the forefront, with the grumpy lighthousekeeper and his estranged daughter in the centre. The results are not great, though, as the dialogue and script could have used some serious polishing. Sole screenwriter H. Haile Chase was primarily a dialogue coach. He wrote a half dozen screenplays, including the sex scare/infotainment film Damaged Goods/V.D. (1961), raising awareness of chlamydia, and the nudie-cutie Paradisio (1962) about a man who acquires a pair of glasses that can see through clothes.

The dialogue and plot do nothing to help the actors, but they try their darndest and all give sincere performances. Les Tremayne, best known for his fairly large role as Maj. Gen. Mann in The War of the Worlds (1953, review), is always good. His velvety barytone and winning charm help carry the film. Forrest Lewis (as the local police) and John Harmon (as Sturges) were talented character actors, often seen in minor roles, and do their thing with conviction. Don Sullivan – as Fred, the boyfriend – was not a bad actor, but didn’t pursue the profession more than five years. Jeanne Carmen is in the film for her looks and reputation, but she’s OK. Frank Arvidson as Kolchek is, if nothing else, expressive, sporting a faux-Slavic accent. The monster is played to perfection by stuntman Pete Dunn. The director’s son Wayne Berwick shows up in small role as a boy who discovers Kolchek’s body. His pronounced limp in the film is not acted – he was affected by polio in real life and wore a leg brace. But he gets up to impressive speed when hopping along!

The Monster of Piedras Blancas could easily have fallen into the category of “worst movies of the decade”, but it’s way too charming for that. Yes, the story is ridiculous, it is completely devoid of logic, the characters are silly, the dialogue awful and the production values near zero – with the exception of the monster. But it is a film made with a lot of heart and enthusiasm. It never feels cynical or like a cash-grab programmer. It’s made by people who loved this kind of films, and went ahead and made it without any money – just with the passion of filmmaking, and somehow pulled it off. It’s a very silly movie, but it’s a little bit like a school play – you just have to love it on some level.

Reception & Legacy

The Monster of Piedras Blancas premiered in April, 1959 in the US, and in the fall of 1959 worldwide. Because of its no-budget, independent nature, it had a very limited release, and caused few ripples. Box office estimates are widely inconsistent, one source reporting a lousy $22 000 gross, and another a $110 000 gross. Whatever the case, it probably didn’t make a lot of money, as the producers didn’t follow through on their five-movie plans.

The film’s obscurity at the time of its release is further confirmed by the fact that it got seemingly got no reviews in the trade or pulp press upon its release. Bill Warren has been able to find one review in the Los Angeles Mirror-News, which described it as a “slow-moving and unwieldy melodrama”.

The film’s credits and marketing tout a claim that it had been given “The Shock Award” by Forrest J. Ackerman’s influential magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland, but Ackerman surely didn’t give it any such award. Bill Warren speculates that the film’s distributors paid Ackerman’s publisher James Warren for the right to use the magazine’s title in their marketing. Ackerman himself has stated that he received letters from fans who went to see the movie on the strength of the magazine’s “award”, and came away disappointed.

The film is surely more popular today than it was back in the day, thanks to a large community who adore old 50s B-movies, many of whom discovered the film through TV reruns over the years. Few modern critics would regard this a good film – but many seem to have a bit of a soft spot for it. All my go-to critics mention the good-looking monster and the severed head as pros. But they also all mention the clumsy, ill-paced script and the often unintentionally funny dialogue.

Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings says: “Still, I always enjoy the easy charm of Don Sullivan and the wonderful voice of Les Tremayne“. In his 2/5 star review at Moria Reviews, Richard Scheib opines that the direction “has the flat, pedestrianness that was common to many of the B movies of the era”. Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum says: “One cool monster (love that drool!) and a plethora of severed heads ultimately aren’t enough to keep the movie afloat. Without them, the film is just another 50’s monster movie, and a pretty bad one to boot.” Mark David Welch writes: “The lead actors are acceptable enough if you’re in a forgiving mood but I have a suspicion that some of the supporting players may have been local residents roped into help. The neighbourhood itself is pretty fine with impressive shoreline and cliffs forming a potentially atmospheric backdrop to the action. Unfortunately, there is much more scenery than action and, by the time events lurch to their predictable conclusion you’ll have probably had more than enough.”

In a positive write-up at Trailers from Hell, Glenn Erickson acknowledges all the film’s flaws, such as the pacing problems, but states: “Instead of being bored, we’re tickled by the unintended deadpan comedy”. Erickson continues: “The Monster of Piedras Blancas knows its market and delivers the goods. People want to see the nasty title critter, and when it shows up it’s quite a shock. […] I like The Monster of Piedras Blancas and feel pretty sure that audiences were more than satisfied.”

Filmed as it was in Cayucos, The Monster of Piedras Blancas has become something of an unofficial mascot of the small town. A lot of the townspeople have memories of or stories about the production, as experienced by themselves as kids or their friends and family. The film is occasionally screened at the local community hall, and the townsfolk keep the memory of the movie alive. As per an article in the San Luis Obispo Tribune, Kolchek’s store is still around, currently serving as an antique shop. For several years, the store displayed a life-size replica of the monster. Local enthusiasts even filmed a 25-minute-long tongue-in-cheek sequel, The Redemption of the Monster of Piedras Blancas, in 2012. It wins no awards for scripting and acting, but is generally quite well filmed for an amateur project. In the movie, a you girl is rescued by the monster after a surfing accident, and it turns out the monster is a kind soul and mean rapper.

Cast & Crew

Director Irvin Berwick, born in 1914, was a dialogue coach and dialogue director, first with Columbia in the 1940s and later with Universal, and he worked with many of the biggest stars in the industry. Berwick was one of the many people who were laid off in the late 40s mass firings at Universal, partly brought on by the troubles caused to the movie industry by the proliferation of the television set. Berwick teamed up with his friend at Universal, special makeup creator Jack Kevan. Kevan had been part of Universal’s makeup department at least from the late 30s and started getting on-screen credit for his work in the late 40s, when he, among other things, collaborated on the monster makeup for Bud Abbott and Lou Costello Meet Frankensten (1948). Along with people like makeup head Bud Westmore and illustrator Milicent Patrick he collaborated on the design of the Gil-man, the aliens from It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), the Metaluna Mutant from This Island Earth (1955, review) and the titular monsters in The Mole People (1956, review). Rather than a designer on paper, Kevan was more often responsible for taking an illustration design and rendering it into a three-dimensional makeup, working with clay, rubber, latex, cotton and spirit gum.

After they had been laid off from Universal, Berwick and Kevan founded their own production company, and their first film was The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959), a super-low-budget film which re-used bits and bobs from Kevan’s previous monster designs combined with a new head and torso to create his last movie monster. The inept but charming little film passed without much fanfare, as did their next few projects in the 60s – now-forgotten exploitation crime dramas. While Kevan retired from the business in the late 60s, Berwick did continue to direct and occasionally write films – even if the handful of movies he made were primarily sex comedies and sexploitation films. Best known is probably the off-the-wall sex/murder drama/comedy Malibu High (1979), which has something of a cult standing. He also popped up in 1982 as associate producer for Larry Buchanan’s universally panned The Loch Ness Horror.

The screenwriter for The Monster of Piedras Blancas is a character by the name of H. Haile Chase who seems to have worked primarily as a dialogue coach and sometime writer. One source credits him as a “well-known stuntman”, but I have found absolutely no sourced backing this up. He does seem to have worked as a stunt driver of sorts on the film Roadracer (1959), but my understanding is that this was only because he happened to be a bit of a gearhead and owned a power car. He is credited with writing a novel that the film Hot Cars (1952) is based on, but there is no record of him having ever published a novel. Chase wrote screenplays for a small handful of low-budget films.

That The Monster of Piedras Blancas is as competently shot as it is is probably thanks to cinematographer Philip Lathrop, who would go on to win two Emmy Awards and was twice nominated for an Oscar. In 1992 he was given a lifetime acheivement award by ASC. Never among the most celebrated DP’s in Hollywood, he is known for shooting such films as The Pink Panther (1963) The Americanization of Emily (1964), Point Blank (1967), Earthquake (1974) and The Driver (1978). Assistant director Joseph Cavalier later became a successful production manager on TV.

The star name of The Monster of Piedras Blancas was Les Tremayne, a well-known radio voice and a respected character actor in the movies. remayne was primarily known from his radio work in the thirties and forties, when he appeared in some of the most popular radio dramas in the country. At one time he was voted one of the three most distinctive voices on American radio, alongside Bing Crosby and Franklin D. Roosevelt. At one time he appeared on 45 different shows in a single week. Tremayne plays the no-nonsense general Mann in The War of the Worlds (1953 review), one of the best military-type performances in a 50s SF movie.

Tremayne kept working in radio, TV and film up until the nineties, although in his later years he mostly did voice work. He appeared in numerous science fiction films: he narrated Forbidden Planet (1956, review), played one of the leads in The Monolith Monsters (1957) and did the rocket launch countdown for From the Earth to the Moon (1959, review). He played the lead in The Monster from Piedras Blancas (1959), and starred as one of the astronauts who land on Mars in Ib Melchior’s psychedelic cult film The Angry Red Planet (1959). He did numerous voices for the English dub of King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and had another starring role in The Slime People (1963). He guested an number of sci-fi TV series in the sixties and dubbed a role in the English version of Antonio Margheriti’s War Between the Planets (1966). One of Tremayne’s longest streaks in a single TV series was his role as Captain Marvel’s mentor in Shazam! (1974-1977). He did voice work on the 1985 animated movie Starchaser: The Legend of Orin, and, as mentioned, appeared in The Naked Monster.

The sheriff in The Monster of Piedras Blancas is played by Forrest Lewis, one of those familiar faces that is always hard to put a name to. Lewis acted on stage, in radio, TV and in films. He didn’t become a regular on the big or small screen until the early 50s, then well into his 50s himself, and would often play sympathetic characters, not seldom in some sort of authority position, like lawmen, judges, doctors or scientists.

Don Sullivan, not a bad actor as such, only had a brief movie career in the late 50s, and played the romantic lead in three monster movies in 1959: The Monster of Piedras Blancas, The Giant Gila Monster and Teenage Zombies. Apparently this was enough for Sullivan, who left the business not much later.

Jeanne Carmen was a pinup model, trick golfer and a fixture at Hollywood parties in the 50s. She was supposedly a good friend of Marilyn Monroe’s and was known for accompanying people like Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra at Hollywood parties. She appeared in around 20 films and TV shows in the 50s and early 60s, mostly in minor roles.

Janne Wass

The Monster of Piedras Blancas. 1959, USA. Directed by Irvin Berwick. Written by H. Haile Chase. Starring: Les Tremayne, Forrest Lewis, Jeanne Carmen, Don Sullivan, John Harmon, Frank Arvidson, Pete Dunn. Cinematography: Philip Lathrop. Editing: George Gittens. Sound: Lapis & Swartz. Makeup: Jack Kevan. Produced by Jack Kevan for Vanwick Productions.

Leave a comment