In 1957 Hammer rejuvenated the horror genre with an emphasis on blood, gore and sex in bright, salacious colours. Somewhat flat and derivative story-wise, the film is more interesting for its legacy than for its qualities. 7/10

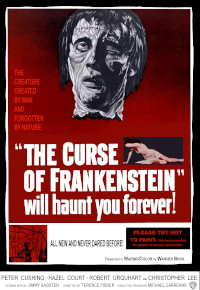

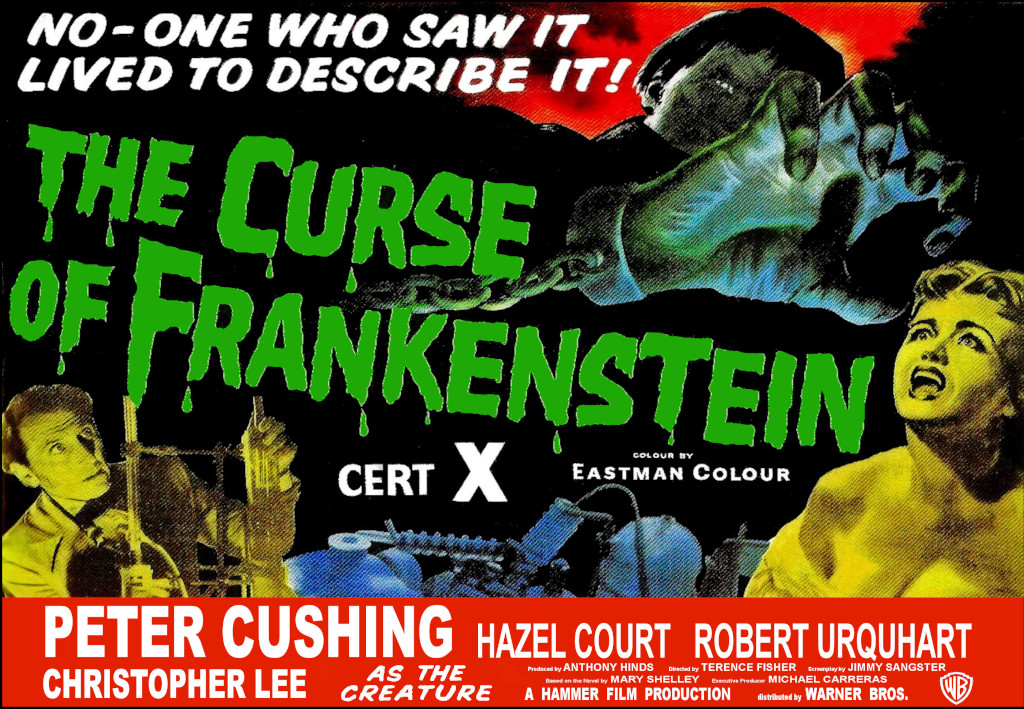

The Curse of Frankenstein. 1957, UK. Directed by Terence Fisher. Starring: Peter Cushing, Robert Urquhart, Hazel Court, Christopher Lee, Valerie Gaunt, Melvyn Hayes, Paul Hardtmuth. Written by Jimmy Sangster. Based on novel by Mary Shelley. Produced by Anthony Hinds. IMDb: 7.0/10. Rotten Tomatoes 7.1/10. Metacritic: 59/100.

Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) begins this film in a jail cell, condemned to death. Desperate to speak to the local priest (Alex Gallier), he begins recounting the story of how he ended up here.

As a young boy (Melvyn Hayes), Frankenstein excelled in school, and after graduating, continued his studies under his mentor Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart). Master soon became assistant, as Frankenstein surpassed Krempe in both knowledge and passion, especially for the secrets of life. After successfully resuscitating a dead dog, Frankenstein convinces a reluctant Krempe to help him not only bring back the dead, but create new life – a new human being. Work is slow, as Frankenstein gathers body parts from graves and charnel houses, and Krempe gradually grows a distaste for the whole business. This isn’t lessened when Frankenstein’s cousin Elizabeth (Hazel Court), his betrothed since childhood, arrives, announcing she is now ready for marriage. Despite his long-lasting affair with housekeeper Justine (Valerie Gaunt), Frankenstein rejoices. Not that marriage is a bliss for Elizabeth, as her husband spends all days tinkering away in his locked lab, with the assistance of Krempe. Finally the day comes when Frankenstein is to insert the brain into his creature, and tells Krempe it will be the brain of a genius. Not long thereafter, Frankenstein invites the venerable Prof. Bernstein (Paul Hardtmuth) to dinner, only to push him off a balcony, to his death. When visiting his crypt after the funeral, Frankenstein is interrupted while carving out Bernstein’s brain by Krempe, who has realised what his old adept is up to and vows to stop the experiment. In the kerfuffle, the brain is damaged, but Frankenstein soldiers on nonetheless. And not long thereafter, Frankenstein turns on his machine, and up rises a hideous giant of a man (Christopher Lee), and his first action is to try to strangulate Frankenstein, who is rescued in the last minute by his old friend Krempe.

So begins Hammer’s 1957 horror revamp The Curse of Frankenstein, a movie that exploded like a bomb in movie theatres, launching the careers of horror icons Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, and forever shaped the future of the small British studio. With its unusually gory visuals (although mostly off-screen) and its vivid, exaggerated colours, The Curse of Frankenstein not only rekindled interest in the classic cinematic horror tales (primarily those filmed by Universal in the 30’s), but turned a new leaf for horror movies in general, with an impact that would resound through cinema for decades.

Eventually the Creature escapes Frankenstein’s lab, and as Frankenstein and Frenke go out hunting for it in the woods, Frenke shoots it in the head and kills it. However, in secret, Frankenstein revives it in his lab, and after brain surgery keeps it frightened and dumb, tethered to a chain in the wall. On Victor’s and Elizabeth’s wedding night, Frankenstein reveals to his estranged friend what he has done, and Frenke storms off, intending to call the authorities on Victor. Frankenstein pursues him, and a befuddled Elizabeth sees her chance to finally find out what her husband has been doing in his lab –– and what Frenke has so frequently warned her about. But while she makes her way up to the attic, the monster breaks loose …

Background & Analysis

In the 20’s the British film industry had fallen considerably behind the international competition, and at one time as few as 5 percent of all films shown in British cinemas were domestically produced. The government then issued a decree that a certain quota of all films in movie theatres had to be British. The quota was successively raised over the coming decades, and gave birth to a number of small studios producing so-called “quota quickies”. Such a company was Hammer, which operated in slightly different forms, beginning in 1934. In 1949 it was practically taken over by Anthony “Tony” Hinds and Michael Carreras, the sons of the two original executives. Hinds and Carreras produced films in a number of genres, but tentatively started dabbling in science fiction and horror with films like The Stolen Face (1952, review) and Four-Sided Triangle (1952, review) and Spaceways (1953, review), all three directed by a former editor called Terence Fisher.

But it was the movie adaptation of the immensely popular TV show The Quatermass Experiment (1953, review) that put Hammer on the map in 1955 with The Quatermass Xperiment (review). Directed by Val Guest, the movie played up the TV series’ horror elements, and deliberately pursued the normally dreaded X-rating by British censors. The film was a resounding success in the UK, and made slight waves in the US as well. Shrewdly, Hammer did their audience research and noted that it was the horror elements, rather than the science fiction, that appealed to movie-goers. One must remember that this was an era when Britain didn’t really produce any horror films, and Hinds and Carreras saw in the genre a very lucrative market niche.

Other films followed, none quite as successful as The Quatermass Xperiment, until US expat producer Max Rosenberg approached Michael Carreras with an idea to make a Frankenstein movie from a script by Milton Subotsky. Hammer liked the idea and considered using the script, but decided in the end that it bore too many similarities to the three first Universal movies. Both men were eventually bought out of the project for £5,000 each, plus a percentage of the profits. Carreras and Hinds gave script duties to Jimmy Sangster, who had previously written the pseudo-sequel to The Quatermass Xperiment, X the Unknown (1956, review), and directorial duties to Terence Fisher, the studio’s top director.

Sangster said in an interview that he had never seen Universal’s 1931 classic (review), and only wrote the screenplay based on his vision of the book. Either Sangster was lying or he picked up the film’s main points through cultural osmosis, because there is a lot in this film that is present in the Universal version that is not present in the book. At one point Sangster even said that he left out the scene of the villagers storming Frankenstein’s castle, because it would have been too expensive to film. That scene originated with the Universal film and is nowhere to be found in the book.

The Curse of Frankenstein also sticks only marginally closer to Mary Shelley’s novel than the Universal films, the main addition being following young Victor’s path from brilliant and enthusiastic student to mad scientist, as well as the addition of housekeeper Justine, who is absent from the Universal canon. However, instead of receiving his education at the University of Ingolstadt, in the film Victor is home-schooled, probably for budgetary reasons. Sangster prided himself in writing his scripts to fit Hammer’s low budgets. The script also leaves out the death of several of Victor’s family members and his work with grief, a carrying theme in the novel, and places the plot almost entirely in the Frankenstein home. Justine is transformed from Victor’s nanny to his housekeeper and mistress, and her death by the creature’s hands is instigated by Victor after she threatens to go to the police when she hears he is about to marry Elizabeth. In the book, the creature’s murder of Justine was his vengeance on Frankenstein for creating and abandoning him.

In fact, the film leaves out the creature’s story and point of view entirely – one of the most important aspects of Shelley’s novel. The Curse of Frankenstein also adopts Universal’s decision to make the creature a mute brute, a hefty departure from the book, where it is eloquent, compassionate and learned (true, this trope was present before the Univeral film, read more on the development of the Frankenstein mythos in my review of the 1931 movie). Sangster, whether or not he had seen the 1931 movie, falls back on its tropes. For example, the scene in which Frenke damages the brain is a throw-back to the assistant Karl (not Fritz) dropping the intended brain and instead taking an “abnormal” brain to Victor. In a weird way, it is almost as if filmmakers wanted to absolve Victor by having his assistants bungle the brain part. On the other hand, Hammer’s Victor actually knows the brain is ruined, but uses it anyway.

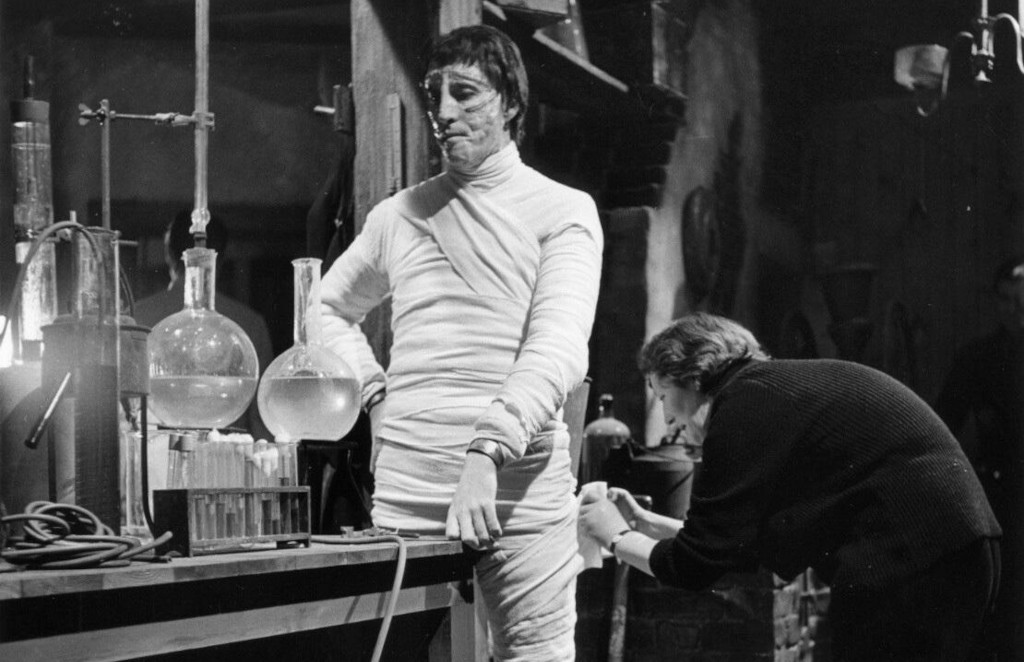

Hammer was consciously trying not to emulate Jack Pierce’s legendary makeup for Boris Karloff, and makeup artist Philip Leakey also dropped the famous flat head and the gaunt-looking cheeks, instead opting for a gorier look for Christopher Lee, with a greyish green face that almost looks like it’s perpetually melting. It’s not a particularly original makeup, but looks like any number of other grotesque B-movie monsters. According to one source, Leakey had tried to create a makeup from a cast of Lee’s face without success, and was forced to improvise the final makeup straight on Lee a day before filming began. Lee doesn’t have much to work with, as the creature’s time on screen is relatively limited and does little more than shuffle around and strangles people, but Lee’s skilful pantomime brings it to life, in particular in the scenes after its “brain surgery”, when it appears frightened and forlorn, chained to the wall. In Lee’s portrayal, its seeming difficulty to control its own limbs lends it a tragic air.

No, this is Victor Frankenstein’s film, and Peter Cushing provides perhaps the ultimate portrayal of the driven scientist. Even if, as film historian Bill Warren points out in his book Keep Watching the Skies!, it is a portrayal that is very far removed from the book. But this is a very different story than the book’s, in which Frankenstein is tormented by guilt over his creation from the moment he brings it to life, and spends most of the book trying to undo his creation. No remorse is ever present in Sangster’s script nor Cushing’s portrayal. Cushing was perhaps best in characters that seemed to cut through obstacles and considerations like a knife as sharp as the actor’s nose. From the get-go, Victor Frankenstein seems to be completely assured of his potential and single-mindedly driven to scientific greatness. This is a man who has devoted his life to uncovering the secrets of the universe and deems all else in life secondary. While he does confront and kill the creature when it attacks Elizabeth, there is no hint that he would have any deeper feelings for her, and seems to treat his marriage mostly as a social facade. His calculating coldness and disregard of human life is clear in the scene where he mockingly dismisses Justine’s anger over him breaking his vows to marry her, and throws her to the monster as if she was simply a piece of meat for a tiger at a zoo.

Cushing excels in a role that he deliberately sought out. According to Warren, Hammer planned to approach Cushing for the film, but hesitated, as they weren’t sure the refined television star would accept. Cushing beat them to the point. He loved James Whale’s 1931 film, and as a young actor in Hollywood in the late 30’s was helped by fellow Brit Whale, and appeared in his 1939 movie The Man in the Iron Mask. When he heard Hammer was remaking Frankenstein, he immediately expressed interest in playing the titular character.

Originally Hammer had considered asking Boris Karloff to reprise the role as the creature, but later realised that they had to refrain from emulating the original films, perhaps partly to stand out, but mainly in order to avoid accusations of copyright infringement. Also, Karloff was 70 years old at the time, and probably wasn’t interested in rehashing his old monster again – a role he consciously steered away from after his three consecutive Universal films. Hammer originally considered comic actor Bernard Bresslaw for the role as the creature, for his 201 cm /6’7 foot height, but settled on 196 cm / 6’5 feet tall character actor Christopher Lee, at the time a relative unknown. According to one story, Lee was chosen because he was cheaper.

Hazel Court would later become immortalised as the scream queen of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, but her role as the proper Elizabeth gives her little to work with here. Character actor Robert Urquhart has been characterised as dull in this role by some critics, but on the contrary, I find his warmth and sincerity, and a certain kind of unassuming quality, a very good contrast to Cushing’s cold, sharp and assertive demeanour. It doesn’t hurt that he reminds me of Jonathan Frakes (Riker) in Star Trek. Melvyn Hayes, 18 at the time, also turns in a good and lively performance as young Victor. Valerie Gaunt is delicious in her role as the feisty Justine, just as memorable as she was as the Vampire Woman a few months later in Hammer’s Horror of Dracula. Unfortunately, Gaunt chose not to pursue a career in acting, and these two remained her only film roles.

The Curse of Frankenstein was not the first horror film to be made in colour, precedents can be found as far back as the early 30’s, with films like Warner’s Doctor X (1932, review) and Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). But in general, few colour horrors had been made. Partly this had to do with the fact that since the introduction of the Technicolor three-strip process, older and cheaper two-strip processes that had been used for the afore-mentioned films was successively phased out: the murky and restricted colour palette of the two-strip colour (it had no blue, for example) was seen as inferior. Technicolor’s three-strip process was cumbersome and expensive, and the Technicolor company was highly protective, and demanded each film made with the process had to have a Technicolor supervisor on set. This meant that the process was primarily used by major studios’ bigger-budget films. Furthermore, colour was primarily seen as contributing mostly to fantasy and more gleeful films, such as costume dramas, musicals and westerns. The general consensus was that colour provided little extra value to crime and horror films, often dark and stark stories inspired by the shadowy cinamatography of German expressionism and noir.

But in the early 50’s Eastman Kodak introduced a new film stock dubbed Eastmancolor (although various names were used, the company didn’t enforce a patented trademark, so for example, Warner called it Warnercolor, and even the original name was used differently, as Eastmancolor, Eastmancolour or, in this case, Eastman Colour). Technically, the process was different from Technicolor in that instead of requiring cameras that shot three films strips through differently hued filters, Eastmancolor instead employed three different coats of colour emulsions (magenta, cyan and yellow) on a single strip of film, making it a far cheaper, if somewhat more restrictive, choice. The Curse of Frankenstein was probably the first horror film produced with the Eastmancolor process, and as such, it held revolutionary potential. And given the fact that British audiences were somewhat unaccustomed to gory horror movies in the first place, the impact of the movie was immediate among British critics and moral guardians.

Terence Fisher’s handling of colour in The Curse of Frankenstein is far removed from the murky shadows of horror movies past. While the reigning philosophy of horror films had previously been to enshroud the viewer in darkness and mystery, often letting the audience’s imagination dream up the horrors of the story, Fisher and cinematographer Jack Asher choose the opposite approach. Fisher’s sets are brightly lit, with vivid, sharp colours, highlighting the movie’s Grand Guignol inspiration. When Frankenstein shops for eyes at the local charnel house, Fisher serves up a pair of real, sloppy eyes (hopefully from an animal) and at another time gives us a pair of dismembered hands in pale, fleshy tones. In a third scene, we see Frankenstein picking glass shards from a red, gelatinous brain. The unnaturally bright colour of blood as Frenke shoots the creature in the face pops out in a shock effect at the viewer. We don’t actually see any surgery, but the camera lingers on Cushing’s focused features as he goes about his business with various tools, forcing the audience to imagine what lies beyond the camera’s reach.

The Curse of Frankenstein revelled in its X rating. British critics were outraged over the gore, but the American counterparts took it more in stride – for the most part, at least.

By 1957 the SF craze was nearing its end. A good amount of science fiction films were still churned out in Hollywood, bur for the most part it was cheap exploitation fair to milk the last of the wave. Studios were looking for something new. The horror genre had been rather dormant since its heyday in the 30’s, with few genuine horror classics released after 1945. The Curse of Frankenstein made for a perfect rite of passage – part SF, part horror, it tested the waters before Hammer plunged into horror full-time with Horror of Dracula (1958). Hammer not only revitalised, but almost reinvented the horror film with The Curse of Frankenstein – this was the turning point from shadow and mystery to shock, blood and gore. With Dracula, Hammer would add the last ingredient: sex, something which is notably absent from The Curse of Frankenstein, with the exception of the voluptuous housekeeper Justine, and a few low-cut dresses worn by Elizabeth.

In truth, the gore of The Curse of Frankenstein is rather tame stuff, and contains nothing that had not been seen in Hollywood movies before. In fact, when watching it today, one is surprised of how bloodless it is, considering Hammer’s reputation for pumping out bucketloads of red syrup. The only blood on display in the entire film is in the afore-mentioned scene in which the creature is shot. And here, also, the actual gore is hidden, as we only see Christopher Lee holding his hand over his face, with blood oozing out from between his fingers. Jello brains and rubber hands had also been staples of horror films since the 30’s. The difference to earlier films, however, is the amount of gore we are presented with. Instead of one or two shock moments, The Curse of Frankenstein serves up scene after scene with nastiness either displayed or suggested. And, of course, for many viewers, this was the first time they would have seen anything like this in colour.

If the amount of gore and blood seems somewhat tame, this is partly the fault of the BBFC, the British board of censors. Producer Anthony Hinds knew the film would be controversial (partly from his experience with The Quatermass Xperiment), and would run into trouble with the BBFC, and so kept in close contact with the censors during production, from script to early preliminary edits and the final film. Paul Frith has written an extremely interesting article regarding the colour use of Hammer’s horror films, and writes a lot about the studio’s dealings with the BBFC. In the article, published in the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television in 2019, Frith highlights the fact that this process was a continuous negotiation back-and-forth between censors and studio. When the censors complained of “unnecessary gore and blood”, Hinds wrote back: “as I am setting out to make a ‘blood chiller’ I must incorporate a certain amount of visual horror as that is what the public will be paying to see”. And while Hammer provided preliminary scenes in unprocessed black-and-white, the BBFC anticipated that any bloody excesses would be all the more shocking in colour, objecting to many such details that would have been acceptable in black-and-white. At one point the BBFC wrote: “There is one cut which I feel sure we shall have to ask you to make and you might as well do it now – and that is the shot in Reel 3 of Frankenstein wiping the blood off on his overall after severing the head. It is also the colour factor which has influenced our request, made above, for the shot of the head being dropped in the tank to be removed.”

On the whole, Terence Fisher’s direction, as far as cinematography goes, is objectively detached, which makes his trademark dramatical zooms and close-up all the more effective. The movie was filmed at Hammer’s home since 1951, a mansion built in the late 19th century in Water Oakley in West London, dubbed Bray Studios. Hammer chose the dilapitated but once lavish mansion partly because it was cheap, but partly because of its interesting architecture and its location — close to essential services, but surrounded by woods and small river, providing multiple shooting locations. Hammer filmed the entirety of several of their films, including The Curse of Frankenstein, in and around Bray Studios. However, the fact that interior filming often commenced in relatively small rooms limited cinematographer Asher’s options when it came to camera placement and movement, making the film seem cramped and somewhat static in many places. For example, we never see more of Frankenstein’s lab than what a 180 degree camera pan would show us, and the same camera angles are used for several scenes.

Despite its indisputable place in the canon of film history, The Curse of Frankenstein is not a great film. If The Quatermass Xperiment had been the first step in Hammer’s new direction, then The Curse of Frankenstein was another large bound. But it wasn’t until Horror of Dracula that the studio really hit its stride. The script by Sangster chooses to focus on Victor Frankenstein, thus leaving his creature in the shadow. This is not a bad decision as such, as it differentiates the film from Universal’s ditto. However, it also reduces the creature to a hulking menace with no personality or agency, turning it into little more than yet another rubbery monster man, the likes of which Hollywood had been saturated with since the early 30’s. Also, despite Cushing’s great performance, Victor remains a one-dimensional character, characterised solely by his singular focus and ruthlessness. He has no character arc or development, nor does he seem affected by either the loss of his friend Frenke, his murderous actions or in any shape or form by his marriage to Elizabeth. It is clear that Sangster has made him into a dark version of Sherlock Holmes (another iconic role for Peter Cushing), and in Frenke we see his Watson, and the conscience of the film. But we never get under the skin of this Victor Frankenstein.

The story touches on potential subplots, but they are never really explored. The Justine strand of the film seems present only as a plot convenience to show Victors ruthlessness, and introduce an suggested element of sex. There’s a hint at a romantic interest between Frenke and Elizabeth, but this mostly seems like a callback to the old horror films in which the female lead was always given a “backup boyfriend” when her fiancé turned out to be a mad scientist or monster.

The Curse of Frankenstein, nevertheless, is a good film, an entertaining, snappily made and visually delicious piece of proto-slasher. It is a film that whets your appetite but doesn’t quite leave you satisfied, but rather hungry for more. And boy, did Hammer deliver more in the years to come.

Reception & Legacy

The Curse of Frankenstein premiered in May in the UK, and was distributed by Warner in the US, giving it considerable muscle when it premiered overseas in June. According to some sources, the movie earned a staggering $8 million on its approx. $270,000 budget worldwide. This was during a period when British film exports had been in decline for several years, and The Curse of Frankenstein was the highest-grossing British movie internationally in a long time. If nothing else, this fact gave Anthony Hinds and Hammer considerable leverage against the BBFC when making the follow-up, Horror of Dracula, in 1958, as it was undisputable that blood and gore benefited the British film industry.

I haven’t found many British reviews from 1957 available online, but the general consenus among film scholars seems to be that a majority of British critics were outraged over the movie’s excess in shock and gore. CineSavant Glenn Erickson writes that “one [critic] suggested that the upstart film be given a new rating, ‘S.O. – for Sadists Only.’”. According to Wikipedia “Dilys Powell of The Sunday Times wrote that such productions left her unable to ‘defend the cinema against the charge that it debases’, while the Tribune opined that the film was ‘Depressing and degrading for anyone who loves the cinema’”. And Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that the original story was “sacrificed by an ill-made script, poor direction and performance, and above all, a preoccupation with disgusting-not horrific-charnelry”.

However, after all the ballyhoo drummed up after its British release, US critics seem to have been disappointed at the lack of horrific content, almost to the point of boredom. The Daily News stated that the Frankenstein story “does not stir the goose bumps anymore”, and called it “tame and overly familiar”. However, the paper still gave the film a 2.5/4 star rating, praising the visuals and the performances. Bosley Crowther at the New York Times called The Curse of Frankenstein a “routine horror picture, which makes no particular attempt to do anything more important than scare you with corpses and blood”. Marion Aitchison at the Miami Herald was more positive, writing: “Designed on a rather fancier scale than the previous Frankenstein shockers, this is in color, which does the best for the gore and the scars of this particular creature.

The American trade press, however, was more attuned to the audience’s tastes. Only Harrison’s Reports seems to have been negatively impacted by the gore, warning that audiences may be sickened by the movie, and that it was not suitable for women or children. However, the magazine also reported: “the photography is very fine, and so is the acting”. The Film Bulletin, on the other hand, opined that “horror and science fiction fans […] will find this a rattling good show, and even the general patronage will be entertained”. The Motion Picture Daily notes the gore, but says that it is palatble as “it is treated more or less in the Grand Guignol tradition of macabre humor”. In fact, the magazine was of the opinion that the colour photography lessened the impact of the monster, as it made it clear that Lee was wearing makeup. The paper thought he looked most of all “like someone who’d fallen into a flour barrel”. Variety was very positive, saying the film “deserves its horrific rating, and praise for its more subdued handling of the macabre story.”. The paper continued: “Peter Cushing gets every inch of drama from the leading role, making almost believable the ambitious urge and diabolical accomplishment. […] Direction and camera work are of a high order.”

Today, The Curse of Frankenstein has a 7.0/10 audience rating on IMDb based on 12,000 votes, a 7.1/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes, a 59/100 rating on Metacritic and a 3.5/5 audience rating on Letterboxd, based on 14,000 votes.

AllMovie gives The Curse of Frankenstein 3/5 stars, with Robert Firsching writing: “Jack Asher’s gorgeous Eastmancolor cinematography and lush sets disguise the low budget, and although Baron Frankenstein’s internal struggle is not as complexly delineated as it would become in subsequent entries, Peter Cushing’s performance remains a fascinating one”. At Empire, Kim Newman insits on mis-naming the leading man as “Peter Gushing”, and gives the movie 3/5 stars. Newman writes: “It’s far from Hammer’s best horror — the first half is bogged down with chat around the dinner table, and Krempe is a scowling plot device who wears out his welcome rather too quickly — but it is the first, and sets the template for all the gothics the company would turn out over the next 15 years. […] In its best scenes, it adds dynamism and British grit to a genre that had previously tried to get by on atmospherics and mood alone. It manages to be shocking without being especially frightening, and its virtues of performance and style remain striking.” TV Guide also praises Cushing’s performance and notes that the film “brought a new seriousness and verve to a genre which had collapsed into self-parody”.

The general critic consensus seems to be that The Curse of Frankenstein is flawed as a stand-alone work, but deserves praise for its genre-shattering impact. It’s seldom seen on lists of best horror movies, although, Rolling Stone magazine does fit it among the 100 best horror films ever made, at position 57. Entertainment Weekly ranks it as only the 16th best Hammer horror movie. Perhaps pulling homeward somewhat, British newspaper The Guardian does rank it as the 2nd best Frankenstein film ever made.

The Horror of Dracula, introducing Christopher Lee as the mantle-bearer of Bela Lugosi and re-casting Peter Cushing as Professor van Helsing, proved that Hammer’s success with The Curse of Frankenstein wasn’t a fluke, and established a formula with far-reaching repercussions. The films’ preoccupation with style, gore, sex and sadism in lurid colour and with a sly smirk, started a ball rolling. In the US, it convinced director/producer Roger Corman to embark on his new career as an auteur exploring the works of Edgar Allan Poe alongside Vincent Price in 1958, and in 1959 inspired the dark German krimi Fellowship of the Frog, which became a massive domestic hit. No doubt the films also gave Alfred Hitchcock the courage to break thriller conventions with Psycho (1960), and Mario Bava to direct his career-making horror movie Black Sunday (1960). In 1964 Bava merged the aesthetics and themes of Hitchcock, the German krimi, Corman’s Poe films and Hammer’s horrors in was his first colour movie, the proto-slasher Blood and Black Lace, which is generally cited as the birth of Italian giallo.

Cast & Crew

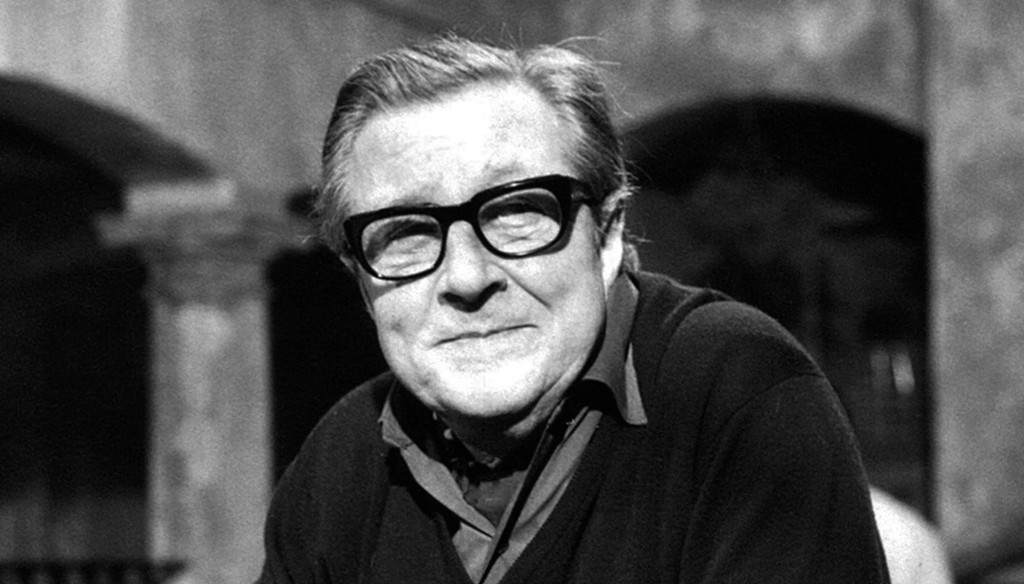

Born in 1904, director Terence Fisher was a late bloomer. After working as a merchant sailor, he decided sea life wasn’t for him, and sought out the movie business. In 1934 he applied to the J. Arthur Rank Studios’ editing deparment, and to his great surprise, was accepted. He got his first editing credit in 1936, and edited around 20 films before he graduated to direction in 1948. He made both A movies for Gainsborough and supporting films for smaller companies. In 1951 he did his first film for Hammer, who liked him, and he became a staple at the studio. Fisher disliked science fiction, but nonetheless made three early SF entries for Hammer, Stolen Face (1952), Four-Sided Triangle (1953) and Spaceways (1953, review). During the 50’s Fisher was a respected workhorse, but had no great name recognition, nor was he particularly defined by any specific style or genre. With the success of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), it was Val Guest who had become the star director of Hammer. A probable reason as to why Guest didn’t direct The Curse of Frankenstein might be that he was busy with Quatermass 2 (1957), the subject of our next review.

It is a matter of debate as to whether Hinds and Carreras actively sought out Fisher to direct The Curse of Frankenstein or if he was simply assigned because he was available. Whatever the case, the film came to change everything for both Hammer and the director. As it so happened, Fisher loved making horror movies, and with the success of The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula, Hammer came to love Fisher, even if it was a love-hate relationship. He didn’t get along with old man James Carreras, the big boss at Hammer, and was at one point fired from the studio after a costly flop in the early 60’s.

Troy Howarth writes in an unusually good IMDb bio: “At the center of Fisher’s work is a fascinating moral dilemma: the seductive appeal of evil vs. the overzealous, frequently close-minded representatives of good. The consistency of theme in Fisher’s work, coupled with a distinctive style achieved through precise framing and a dynamic editing style, refutes the idea that he was merely a hack for hire, while lending his films a recognizable signature.” These themes, coupled with Fisher’s distinctive visual flair, made him natural for Hammer’s horror movies, of which he directed the large bulk during the late 50’s and 60’s, into the mid-70’s. All in all, Fisher directed 29 films for Hammer, 12 starring Christopher Lee and 13 starring Peter Cushing. Naturally, he is best remembered for his Frankenstein and Dracula films, of which he directed several, Horror of Dracula (1958) and Revenge of Frankenstein (1958, review) often considered the best, but there are others worthy of mention, like The Mummy (1959), The Hound of Baskervilles (1959), Fisher’s personal favourite, the melancholy The Gorgon, and the Lovecraftian The Devil Rides Out (1968). Outside of his Hammer ouvre, his best known film is perhaps the SF thriller Night of the Big Heat (1967), made for Planet Film.

Fisher directed 12 SF movies: Stolen Face (1952), Four-Sided Triangle (1953), Spaceways (1953), The Curse of Frankenstein (1958), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959), The Earth Dies Screaming (1964), Island of Terror (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Night of the Big Heat (1967), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974).

A road accident in 1968 forced Fisher into a break, which effectively became the end of his directing career. Despite his films’ enormous commercial success, especially in the late 50’s, Fisher received few accolades during his lifetime. British critics generally considered Hammer’s horror output as either offensive or trashy, or simply of little artistic value. His death in 1980 passed almost completely unnoticed by the press and the general public. It wasn’t until a decade later that Fisher and the Hammer horrors started undergoing a popular resurgence and a critical re-evaluation. Fisher did win a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation for Horror of Dracula in 1959 (shared with Jimmy Sangster).

With his laser focus and piercing blue eyes, Peter Cushing became an almost instant horror icon in 1957. For two decades he became synonymous with Hammer horror, making his own the characters of Victor Frankenstein, Abraham van Helsing and Sherlock Holmes. Cushing, born in 1913, pursued acting at a young age, appearing on stage before making a brief detour to Hollywood 1939-1941. After serving in WWII, he returned to the stage and in the early 50’s became a minor star of British TV, which at the time consisted mostly of teleplays — his performance in the BBC adaptation of 1984 is particularly well remembered. He also has the distinction of being one of the many Dr. Who’s, even if he never played the character in the TV series, but in two rather poorly received movie spinoffs in the mid-60’s. Cushing found a whole new audience in 1977, when he appeared as the ominous Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977). Cushing retired in 1986 and passed away in 1994. He won a best actor BAFTA in 1956, and has been awarded several lifetime awards for his contribution to genre cinema. In 1977 he was nominated for a best supporting actor Saturn Award for Star Wars.

While best known as a horror actor, Peter Cushing appeared in 18 science fiction movies. Cushings SF films include: 1984 (1954), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965), Island of Terror (1966), Dalek’s Invasion of Earth 2150 A.D. (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Night of the Big Heat (1967), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), Scream and Scream Again (1970), Horror Express (1972), The Creeping Flesh (1973), Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974), At the Earth’s Core (1976), Star Wars (1977), Shock Waves (1977) and Biggles (1986).

During his early career, Cushing acted twice in the same films as Christopher Lee, but the two never met before The Curse of Frankenstein. Born in 1922 of minor nobility with Italian family roots, Lee worked menial jobs before joining the war effort in 1939, originally as a volunteer assisting my home country Finland against the Russians during the Winter War. He and the other British volunteers were put on guard duty a safe distance from the border and returned home after two weeks. Lee served in the RAF from 1939 to 1946, leading troops in Africa and Italy, and after the war put his wide language skills to use in hunting down Nazi war criminals. In 1947 he joined the Rank organisation as an actor, and acted in numerous films and TV shows in the late 40’s and 50’s, but struggled to find proper roles because of his height. As such, his thankless casting in The Curse of Frankenstein — a role he got because he was tall and cheap — turned out to be a career-defining “bit-part”. Horror of Dracula launched him into international fame, one that would be both a curse and a boon.

The late 50’s and early 60’s were extremely busy times for the over 6-foot, 200 centimetre actor, whose greatest assets lay in his commanding voice and regal bearing, which lended themeselves perfectly for roles as megalomanic villains, authority figures and supernatural beings. During his career he appeared in a whopping over 200 films, an incredible number for an actor who was almost always in a featured role. Few actors have appeared in so many iconic franchises (except perhaps Peter Cushing). From Dracula, Frankenstein and the Mummy, his next Big Franchise role was that of villain Scaramanga in the James Bond film The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). However, before that he starred in what is often cited as one of his best performances, the atmospheric and erotic horror movie The Wicker Man (1973). In 1962 he took his first of stab at the role of Sherlock Holmes in the German film Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace. He may be the only actor who has played both Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes in film. From 1965 onward he played Fu Manchu in a series of movies and in 1966 portrayed the infamous Russian medic and mystic Rasputin in Rasputin, the Mad Monk.

After his Hammer horror fame, Christopher Lee was never out of work, even if the films he appeared in were seldom of the highest quality. The 80’s and 90’s, in particular, saw him cast primarily in low-budget schlock and TV films. His name almost soleley associated with his Dracula and other Hammer Horror work, Lee was out of the spotlight, seen as something of a washed-up kitsch star of the past. This all changed in the early 2000’s, when he was thrust back in the spotlight and discovered by a whole new generation of movie-goers in two of the biggest movie franchises in history. In 2001 he made his debut as Saruman in Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, a role he reprised in all three movies, as well as the later Hobbit films. And in 2002 he joined his friend Peter Cushing in the Star Wars universe as the Sith Lord Count Dooku in Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones. Lee, true to his lifelong habit, kept working up until his death in 2015.

Cushing and Lee were lifelong friends, and like Cushing, Lee never received any of the big awards, despite his later popularity — although he did get a BAFTA lifetime achievement award, and dozens of genre awards. Fluent in several languages, Lee made films all over the world, and was at one time put down for a Guinness world record for most screen credits by a living actor — perhaps a somewhat dubious claim. Lee appeared in over 20 science fiction movies, and I will not list them all here. Keep following the blog for all of them!

Hazel Court was a veritable scream queen on both sides of the Atlantic. Like Christopher Lee, Court studied at the Rank Organisation’s “Charm School”, an acting school mimicking Hollywood studios’ “grooming schools” for potential future stars. She acted in some two dozen films before her rise to fame as a horror star, sometimes in leads, but often in supporting roles. Her first brush with science fiction was as the ingenue in the cult film Devil Girl from Mars (1954, review), remembered for featuring Patricia Laffan in a tight-fitting latex suit. The Curse of Frankenstein was Court’s first proper horror appearance, and she became a Hammer favourite. In the early 60’s, she relocated to Hollywood, where she often appeared as guest star on TV shows, and occasionally in movies. She is primarily remembered for appearing in three of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations for AIP: The Premature Burial (1962), The Raven (1963) and The Masque of Red Death (1964).

The role of young Elizabeth in The Curse of Frankenstein was played by Court’s daughter with her first husband, Sally Walsh. Her second husband Don Taylor also appeared in several Hammer films. Taylor later went on to become a succesful director, noted for the SF films Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) and The Island of Dr. Moreau (1977). Hazel Court’s other science fiction outings were The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959) and Doctor Blood’s Coffin (1961).

Reality mirrored the fiction in the case of Robert Urquhart, playing Frankenstein’s mentor and friend Paul Frenke. Urquhart was initially excited about appearing in The Curse of Frankenstein, but grew wary of the film’s gory elements. At the premiere, he stormed out of the theatre halfway through the movie. He burned his bridges to Hammer by speaking out against the movie in public. However, the film remains his best known role by far, as he was primarily a supporting actor on TV.

The actor playing young Frankenstein is Melvyn Hayes, a former chilf actor who would go on to some TV fame in the Uk for portraying the drag artist/soldier in the BBC WWII sitcom It Ain’t Half Hot Mum (1974-1971). He later embarked on a successful career as a voice actor. German-born Paul Hardtmuth portrays the scientist whose brain ends up inside the Creature. Character actor Hardtmuth showed in the SF movies Highly Dangerous (1950, review), Timeslip (1955, review), The Gamma People (1956, review) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957).

Janne Wass

The Curse of Frankenstein. 1957, UK. Directed by Terence Fisher. Starring: Peter Cushing, Robert Urquhart, Hazel Court, Christopher Lee, Valerie Gaunt, Melvyn Hayes, Paul Hardtmuth. Written by Jimmy Sangster. Based on the novel Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Music: James Bernard. Cinematography: Jack Asher. Editing: James Needs. Production design: Bernard Robinson. Costume design: Molly Arbuthnot. Makeup: Philip Leakey. Sound: Jock May. Visual effects: Les Bowie. Produced by Anthony Hinds for Hammer Films.

Leave a comment