A dying businessman wants to replace his brain with that of Nostradamus, but Nostradamus has other plans. Low-budget SF legend W. Lee Wilder directed this unintentionally hilarious 1957 British clunker. 4/10

The Man Without a Head. 1957, UK. Directed by W. Lee Wilder & Charles Saunders. Written by William Grote. Starring: George Coulouris, Robert Hutton, Nadja Regin, Julia Arnall, Sheldon Lawrence. Produced by Guido Coen. IMDb: 4.6/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

The ageing, self-centered New York stock millionaire Karl Brussard (George Coulouris) learn he has an incurable brain tumour. He travels to London to see a specialist, Dr. Merritt (Robert Hutton) who says he can transplant a new brain into Brussard’s body, and that Brussard’s body could force it to take on his personality. According to Merritt, it doesn’t matter how long the donor has been dead, as long as he has been properly embalmed. Brussard won’t accept just any brain into the skull of the great Karl Brussard, so he goes window-shopping to Madame Tussaud’s, where he learns of Nostradaums, “the greatest mind of his generation”. Off Brussard pops to Paris, where he visits Nostradamus’ crypt and cuts off his head.

This is the incredible beginning to the ludicrous British-produced 1957 movie The Man Without a Body, released just weeks after Hammer’s groundbreaking brain transplant film The Curse of Frankenstein (review). Frankenstein was considered cheap, as it was produced with a budget of £65,000. This film was produced on £20,000. And friends of 50’s low-budget SF films will know what we are up against when I say that it is directed by W. Lee Wilder.

Back in London, Dr. Merritt is able to revive old Nostradamus (Michael Golden), and keeps his head on his table, connected to tubes and a mechanical lung and heart. Brussard tries to assert his dominating personality over the newly-awakened mind of Nostradamus, convincing him that he is, in fact, not Nostradamus, but Karl Brussard. But in Nostradamus, Brussard has met his match, and the 400-year old astrologer refuses to budge. Shortly after, Brussard’s brain tumour starts messing with his memory and mental capacity, so he seeks advice from the smartest brain in the world, that of Nostradamus, about what to do with his oil shares. Nostradamus, knowing that the price of oil is plummeting, tricks Brussard into selling all his shares, which eventually ruins Brussard.

Meanwhile, Brussard’s young gold digger mistress Odette (Nadja Regin) has been cheating on Brussard with Dr. Merritt’s assistant Lew (Sheldon Lawrence). When she learns Brussard is broke, she packs her things and goes to Lew’s apartment while Lew is at work. Brussard follows her in his car, and strangles her in jealousy. He then waits for Lew to arrive, gun in hand. Lew manages to escape, and runs to Merritt’s lab, where Brussard catches up with him and shoots him in the back. He then shoots the tech keeping Nostradamus alive. When Merritt and nurse Jean (Julia Arnall) examine Lew, they conclude the “cranial nerve has been severed”, and that the only way to save both him and Nostradamus is to transplant Nostradamus’ head onto Lew’s body. But when Lewstradamus wakes up, they have become a monster, lost the ability to speak and began walking like a parody of Frankenstein’s monster. Lewstradamus breaks out and goes into a church tower, where he is followed by Brussard, with the doctors and the police in tow. At the top of the tower, Brussard gets dizzy and falls to his death. Lewstradamus rings the bell, and (intentionally? accidentally?) hangs himself in the bell rope. Lew’s body comes crashing down, while Nostradamus’ head remains dangling in the rope. The end.

Background & Analysis

I let out a deep sigh of frustration around 10 minutes into this film, when I realised this would be one of those movies that are built on the ridiculous notion that you can swap out your brain and still remain the same person. Fortunately, screenwriter William Grote does foresee the obvious counter-arguments and deflects the story in a slightly different direction, even if the basic idea remains.

I haven’t been able to suss out exactly what the background to The Man Whithout a Body is. It is directed by New Yorker W. Lee Wilder, brother of famed director Billy Wilder, and produced by Italian-British producer Guido Coen for the independent production company Filmplays, and filmed in London. One reason might be that foreign productions producing films in the UK could apply for a government grant, if they employed a certain quota of British cast and crew, as well as a British director. This, according to lead actor Robert Hutton, is why Brit Charles Saunders is listed as co-director on the movie. According to Hutton, Saunders showed up to set every day, but didn’t do anything. Saunders was a frequent collaborator of producer Coen’s and together they made the SF/horror film Womaneater (review) the next year (starring Vera Day, who played the female “lead” in Quatermass 2, the subject of my last review).

Whatever the case, the film was written by William Grote, his only screenplay. I haven’t found much information on Grote, but he seems to have written at least one pulp novel as well, Uneasy Lies the Head, which, surprisingly, has nothing with brain transplants to do. W. Lee Wilder was a purse manufacturer in New York who saw his alienated brother Billy write to such heights as a movie director, and in 1945 decided he could do the same, and used his accessory earnings as entrance into the movie business. Apparently, Wilder the elder didn’t have quite the same knack as his brother, and churned out a string of crime programmers and short films between 1945 and 1951, when he hit upon science fiction, and produced a “trilogy” of so-bad-they’re-good science fiction movies with widely different themes, as if trying on different popular tropes. These have since become his most lasting legacy.

The Man Without a Body was Wilder’s fourth SF movie, and he now tackles the old brain-in-a-vat trope, popularised in 1942 by Curt Siodmak’s novel Donovan’s Brain. Grote mixes up the elements enough so you can’t claim the movie plagiarises the book, but the elements are all there. In the book, a scientist preserves the brain of a ruthless businessman, Donovan, in a vat, and slowly Donovan’s brain starts telepathically controlling the scientist into continuing his shady business dealings. The film contains a dying businessman, a “brain in a vat”, so to speak, of a brilliant and ruthless man, and in a way Nostradamus starts controlling Brussard by tricking him into ruining himself through business dealings.

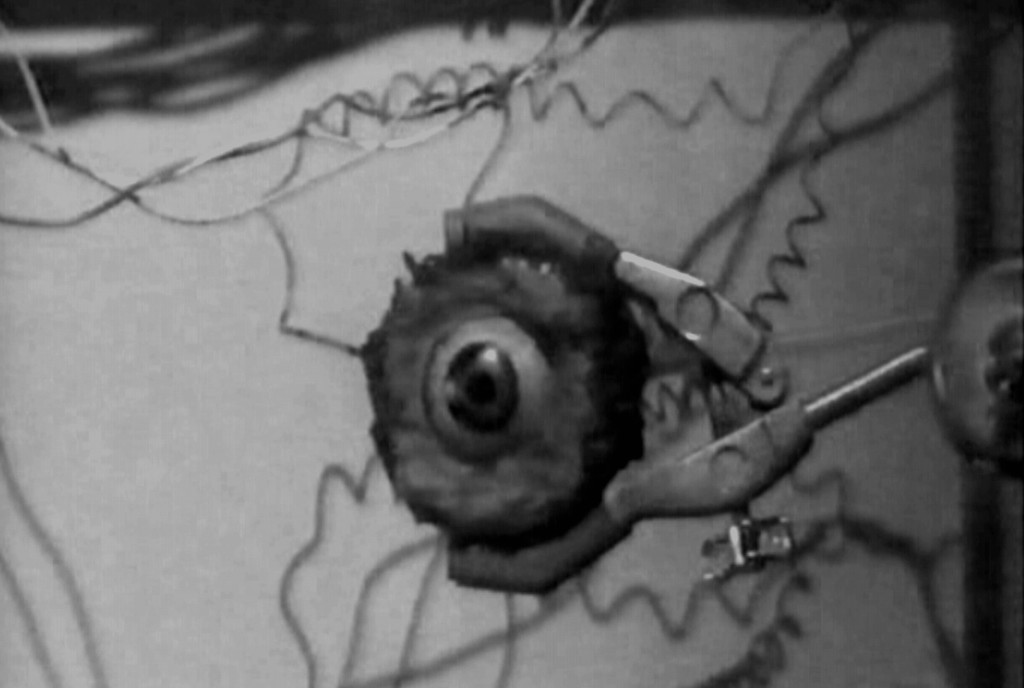

The Man Without a Body is a bizarre mix between the cheerfully ridiculous story and the no-nonsense crime thriller direction. On the one hand, it features a doctor who in his lab has a menagerie of oddities – icky organs in jars, some hooked to electrical appliences and mechanical lungs and hearts, pumping and pulsating. On a table, attached to tubes and electrodes is the living, severed head of a monkey, and suspended from a wire frame an single eye in a socket, which occasionally moves to take a look at what is going on – sometimes seemingly engaging is staring competitions with Brussard. Among all this weirdness you would suspect to have John Carradine chewing up the scenery, spouting about creating a new master race. But instead we get Robert Hutton, a suave and friendly-looking American guest star, who acts as he was the manager of an ordinary dentist’s salon. When Brussard arrives with a 400-year old, mummified head, Dr. Merritt hardly raises an eyebrow. His two assistants, Lew and Jean also act as if they were merely spending their days removing plaque and fitting dentures, not transplaning brains while being observed by a free-floating eye on a wire frame.

The script is completely bonkers, of course, from the idea that one could somehow “imprint” one’s own personality on a brain and the have it plonked into one’s own body, which would then “force” the brain to take on the characteristics of the host, to the wholly unscientific idea that a 400-year old brain would still be completely intact having been, in essence, mummified. Even accepting these for the sake of suspension of disbelief, the script is an odd one. Given the many great minds and businessmen to choose from, it seems odd that Brussard would choose Nostradamus, a 16th century apothecary and astrologer, as the tool of his “resurrection”. Much ado is made about Nostradamus’ alleged powers as a “seer”, but the script ultimately makes little use of the possibilities presented. Long stretches of the film are devoted to Brussard’s French mistress Odette and her affair with Lew, but this is abruptly discarded when Brussard strangles Odette and shoots Lew. The sole purpose of this subplot seems to be to give Brussard a reason to shoot Lew, and thus give Merritt a reason to inadvertedly create a monster. The character of the nurse/assistant Jean is one which seems to serve no plot purpose whatsoever. The script does show, in no unclear terms, that Jean is in love with Merritt, but he brushes off her invites in a kind and polite way, and the potential love story here just stops dead in its tracks, making it completely redundant.

The character arcs, if they exist at all, are muddled to say the least. Brussard is obnoxious, self-centered and desperate from the first scene to the last, really doesn’t undergo any psychological changes throughout. Odette makes it clear from the get-go that she is only interested in Brussard’s money, and is on the lookout for a new hubby. The fact that she chooses a poor medical assistant shows another side of her personality, but Nadja Regin plays her as such a scheming and devious femme fatale, that it is difficult to have much sympathy for her. Lew the assistant is on screen for such a short time, that we don’t really have an opportunity to care much about what happens to him. Dr. Merritt is no more than a plot device and as stated Jean doesn’t seem to serve any function other than the film needed an ingenue. The only person we can really feel any sympathy with is poor Nostradamus, and he is a rubber head on a table.

However, the story manages to follow its own warped logic, and progresses fairly smoothly. The direction by Wilder is quite dull, but there are a few interesting camera angles here and there, and the film relies much less on stock footage than his previous SF efforts. Unfortunately, the cinematography is very murky in places. The film is obviously cheap, but doesn’t feel as cheap as, for example, Phantom from Space (1951, review), which squeezed actors into corners of what was probably Wilder’s own office. The design of the monster in the end is bizarre. For some reason, Wilder thinks that a head tranplant would require a ginormous rectangular block of plaster to be erected arond the head, which gives Lewstradamus the look a some weird Spongebob character, or a big walking molar.

Character actor George Coulouris chews the scenery in a wonderfully over-the-top performance as Brussard. Ukrainian-Yugoslavian actress Nadja Regin chews away similarly as Odette, but with much less talent. Robert Hutton is pleasant and competent in the role as Merritt and the rest of the cast are all equally competent, even if they don’t have all the much to work with. Michael Golden in the role of Nostradamus has the thankless role of popping his head through a hole in a table and delivering his lines from behind a rigid rubber mask.

This is far from the worst film by W. Lee Wilder we have reviewed. And even in his worst efforts, there have always been something resembling an interesting idea at heart. The same goes for The Man Without a Body. There is a good story hiding there somewhere among the ludicrousness, but Wilder isn’t the director to bring it to the front, getting lost in pointless subplots along the way. These subplots, as you realise they are secondary to the story, do much to bog the film down. But there is a hysterical charm to this picture, placing it firmly among films that should be seen by all friends of old so-good-they’re-bad movies.

The Man Without a Body was released in the UK on a double bill with Half Human, the Americanised version of Ishiro Honda’s snowman film Ju jin yuki otoko (1955, review), with a frame story/narration by John Carradine added by editor/director Kenneth G. Crane. In the US it was released alongside Wilder’s own horror movie Fright. In the UK, the film received an X rating. In fact, as far as ick goes, this is a far more explicit film than the much talked-about The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review).

Reception & Legacy

The Man Without a Body seems to have gone wholly unnoticed by both newspaper critics and trade journals in the US. In British papers I can only find a few short notices, calling the film “unlikely” and “predictable”.

Currently the movie has a 4.6/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on close to 400 votes, and not enough ratings on either Letterboxd or Rotten Tomatoes for a consensus, speaking to the film’s obscurity. Allmovie gives it 2.5/5 stars and TV Guide calls it a “very absurd film”. Richard Scheib at Moria gives The Man Without a Body a lowly 1/5 stars, calling it a “dreary programmer” that “makes no real sense”. Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster writes: “This is an odd, little film, which doesn’t quite seem to know what to do with its discordant elements. […] It really needed to be a little crazier – or perhaps, a bit more straight-faced serious.” Ilja Rautsi at Finnish Elitisti writes “Somewhat surprisingly, The Man Without a Body isn’t a full-blown turkey all the way through, as the storytelling is very smooth and even logical throughout the movie. Especially considering the nature of the proceedings.”

Cast & Crew

We have written about W. Lee Wilder before on Scifist, and for a longer rundown of his career, see for example my review of Phantom from Space (1953). In short, Wilder decided to become a filmmaker around the same time as his brother Billy Wilder had his American breakthrough in 1945. Willie produced a couple of noirs and directed a few short films before making his feature debut as a director in 1950. Phantom from Space (1953) was his third film as a director, and the first in his SF “trilogy”, which also contains Killers from Space (with aliens with ping pong ball eyes, 1953, review) and The Snow Creature (1954, review). These three have become his most lasting legacy, and are often considered among the worst of the science fiction cheapos made in the decade. He directed eight more films in the fifties and sixties, including more noirs, retro-horrors, like the sci-fi The Man Without a Body (1957) and a last science fiction movie called The Omegans (1968). To differentiate himself from his brother Billy, Willie chose to credit himself as W. Lee Wilder.

Italian-born producer Guido Coen came to England in 1929, and soon found work at the production company Two Cities, a long time as a film subtitler, and later as an assistant producer. In 1949 he set up his own production compay, specialised in quota quickies. In 1959 he joined Twickenham Studios in London, first at lower positions, but eventually as executive director. He oversaw extensive development of the site, on which numerous classic films were shot, from Alfie (1969) to Blade Runner (1982).

George Coulouris was a celebrated stage actor who began his career in London, but made the move to New York in 1929. Here he regularly appeared on Broadway, and was a longtime member of Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre. He also worked extensively in radio, and was the first actor to voice the extremely popular agent Bulldog Drummond on the air. He made his film debut in 1933, and established himself as a major film actor in 1941, when he played the Kane family lawyer in Citizen Kane (1941). During his Hollywood heyday Coulouris appeared in such films as For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), Watch on the Rhine (1943) and Mr. Skeffington (1944). He returned to the UK in the early fifties, where he divided his time between prestigious stage roles and rather mundane film roles. He appeared in the science fiction movies The Man Without a Body (1957), Womaneater (1958) and Peter Fonda‘s nihilistic post-apocalypse film No Blade of Grass (1970), as well as A Clockwork Orange (1971). His last SF work was in the odd The Final Programme (1973).

American Robert Hutton enjoyed what one might perhaps call a comfortable but somewhat uneventful movie career, with a slight stint of stardom during WWII, when he had a string of leading man roles in minor movies thanks to his resemblence toJames Stewart. During the 50’s he relocated for a while to the UK, before returning to American soil. Hutton is well-known to fans of science fiction because of his leads in The Man Without a Body (1957), Invisible Invaders (1959), The Slime People (1963), The Vulture (1966) and They Came from Beyond Space (1967). He also appeared in The Colossus of New York (1958, review) andTrog (1970).

Ukrainian-born Yuogoslavian Nadja Regin grew up in current-day Serbia, where she acted from a young age, graduated form the Belgrade Theatre Academy, and soon began appearing in Serbian films. Through participation in German-Yugoslavian movies, she relocated to Germany, and then to London in the mid-50’s, despite not speaking a word of English. She later considered the move a “career suicide”, as she was only offered roles of “foreign girls”, meaning femme fatales and spies. She is best known for appearing on two James Bond movies, From Russia With Love (1963) and Goldfinger (1964).

Julia Arnall was born in Berlin in 1928 as Julia Ilse Hendrike Irmgard von Stein Liebenstein, and married a British officer station in Germany in 1950, and moved to England, where she continued her career as a model and actress. She had a string of leading lady roles in B movies in the 50’s, before she segued into TV. She quit acting in 1969.

The rest of the cast are made up of reliable British bit-part players, such as Peter Copley, Maurice Kaufmann, Donald Morley, Frank Forsyth and Ted Carroll. Copley, for example, can be seen as the strict dining hall master in Roman Polanski’s Oliver Twist (2005), and had small roles in a handful of SF movies, for example as the principal in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969).Maurice Kaufmann played Professor Quatermass’ assistant Marsh in The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review) and the mini submarine officer in Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review). Ted Carroll is an instantly recognisable bit-part actor due to his smashed nose. He is probably best known for being prominently feautured as Biro the Hawkman in Flash Gordon (1980).

In a small role as a maid we see pretty Kim Parker, whom we’ve covered before as one of the aliens maidens in the clunker Fire Maidens from Outer Space (1956, review). Parker’s film career lasted little more than five years, one of many young women hoping to make it in the business, only to find opportinities for women in film are fewer than men’s, and that managing the crushing 50’s expectations on being a wife and a mother was hard enough even without navigating a fickle and uncertain film career. Parker did have time to appear in The Man Without a Body (1957) and even played the lead in Fiend Without a Face (1958, review).

Janne Wass

The Man Without a Head. 1957, UK. Directed by W. Lee Wilder & Charles Saunders. Written by William Grote. Starring: George Coulouris, Robert Hutton, Nadja Regin, Julia Arnall, Sheldon Lawrence, Peter Copley, Michael Golden, Norman Shelley, Stanley van Beers, Tony Quinn, Maurice Kaufmann, William Sherwood, Kim Parker. Music: Albert Elms. Cinematography: Brendan Stafford. Editing: Tom Simpson. Art direction: Harry White. Makeup: Jim Hydes. Sound: Cyril Collick. Produced by Guido Coen for Filmplays & Eros Film.

Leave a comment