After surviving a nuclear explosion, Glenn Langan is moved to a military test site where he continues to grow ever larger. There’s a rugged charm to Bert I. Gordon’s 1957 film that helps counteract the dull script and the poor effects. 5/10

The Amazing Colossal Man. 1957, USA. Directed by Bert I. Gordon. Written by Mark Hanna, Bert I. Gordon, George Worthing Yates. Starring: Glenn Langan, Kathy Downs, William Hudson, Larry Thor. Produced by Bert I. Gordon. IMDb: 4.6/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 5.4/10.

Lt. Col. Glenn Manning (Glenn Langan) gets burnt to a crisp during an accident while testing a new plutonium bomb. Dr. Lindstrom (William Hudson) gives him little chance of survival, but when his fiancée Carol (Cathy Downs) visits him the next day, his skin has miraculously healed and no trace of the accident remains. However, she is informed by the authorities, led by Maj. Coulter, MD (Larry Thor) that she will no longer be able to visit him. When she returns the next day, Glenn has vanished from his room and the hospital has no record of him having ever been treated there. After being stonewalled on all fronts, Carol manages to find out that Glenn has been moved to a military medical research facility. She drives to the facility and sneaks in to Glenn’s room, only to find that Glenn has grown to enormous size.

The Amazing Colossal Man from 1957 is a cult classic directed by the original Mr. B.I.G., Bert I. Gordon. This is considered by many to be one of Gordon’s best movies, although that is not necessarily saying much. It was Gordon’s first collaboration with American International Pictures, and was released on a double bill with the British co-production Cat Girl.

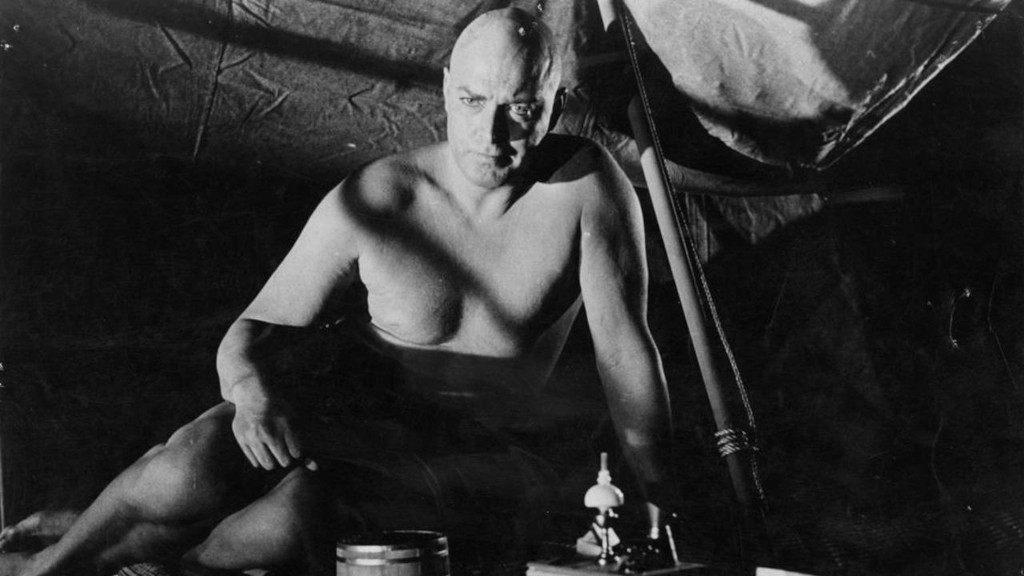

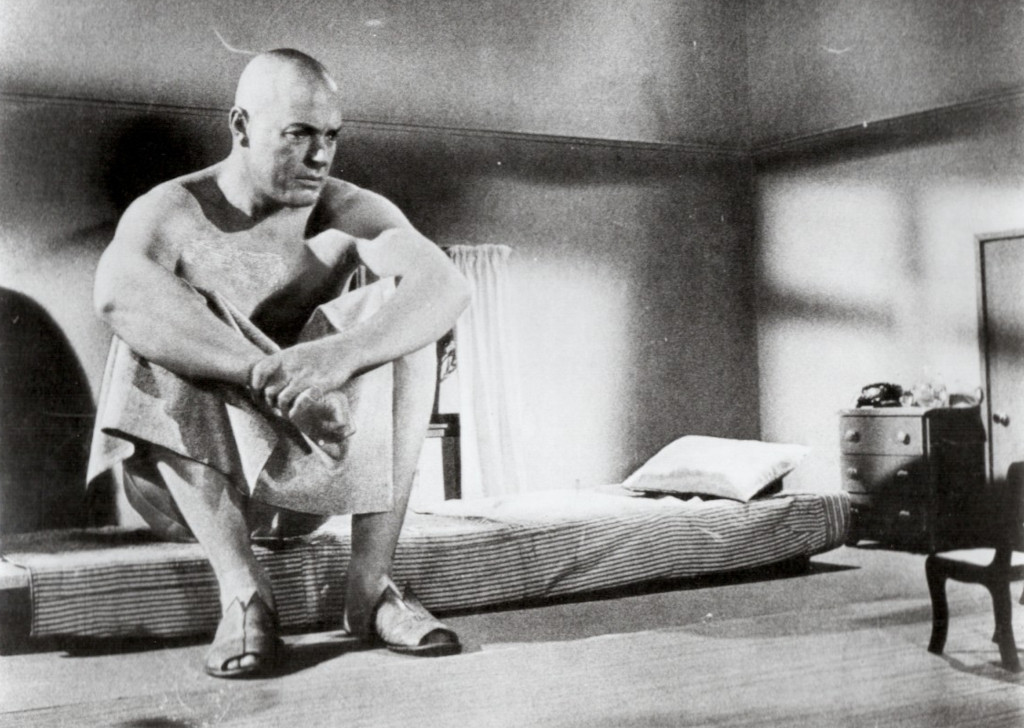

Dr. Lindstrom explains to Carol, with very much science gobbledy-gook, that Glenn will continue growing unless the scientists can find a cure. The military tries its best to accommodate the growing giant, making him a bedroom in a circus tent, creating for him an adjustable “sarong” as he calls it, but it looks like a diaper, which he can keep adjusting as he grows, and ordering truckfuls of food. Glenn copes with a sarcastic attitude, whole Carol does her best to comfort him and keep his spirits up, to little avail.

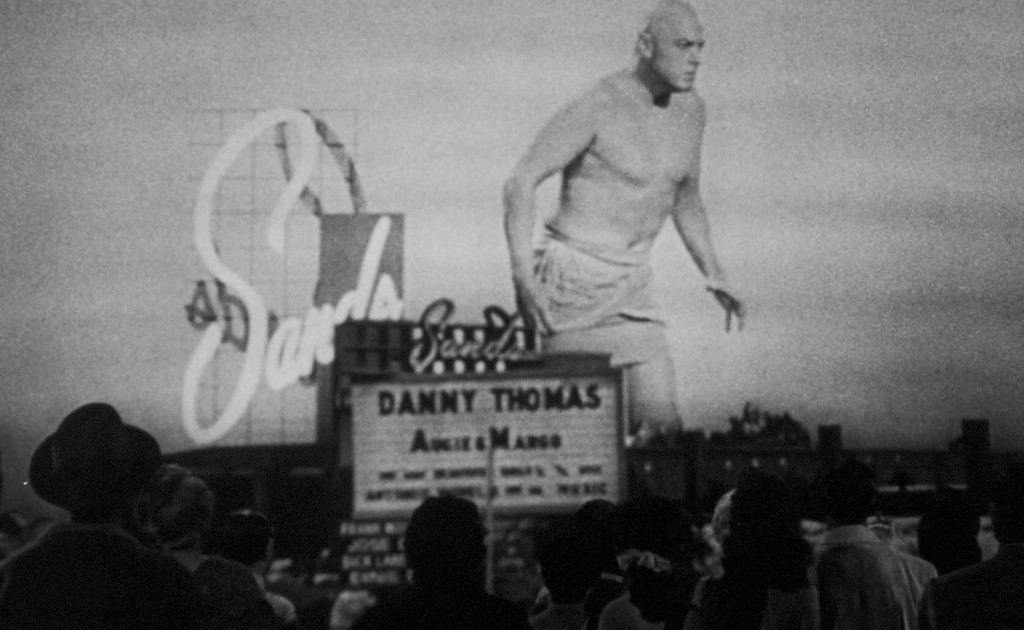

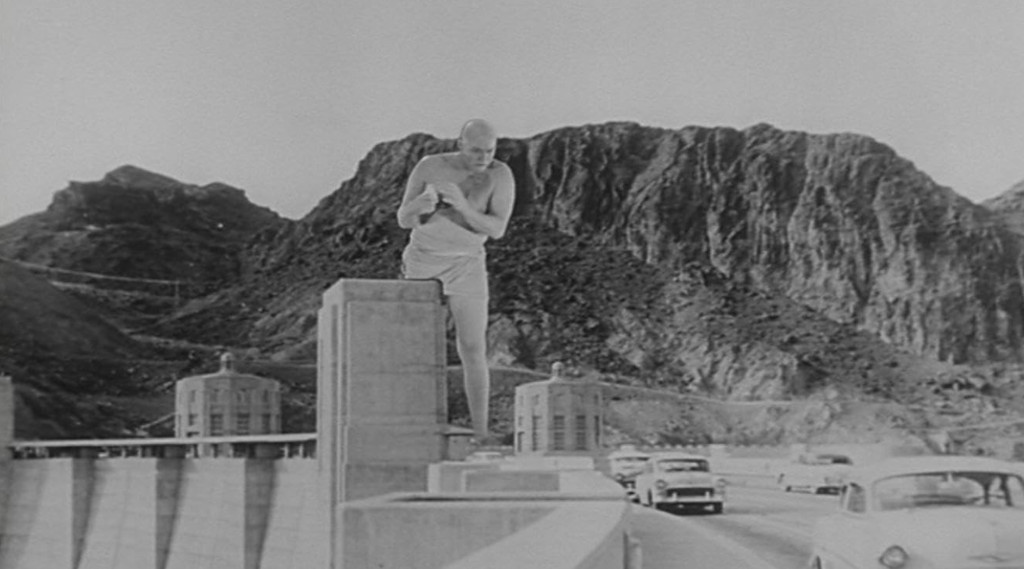

Dr. Linstrom and Maj. Coulter eventually explain to Carol that Glenn has mere days left to live, as his heart is not growing at the same rate as the rest of his body, which will result in him first going insane and then dying. And, true enough, Glenn loses his mind and goes on a rampage through Las Vegas, stopping at one point at a window, watching a young woman bathing. Meanwhile Lindstrom and Coulter have come up with a cure, a serum that will first arrest his growth, and a radiation treatment that will turn him back to normal size. The trio set off in a helicopter, armed with a giant syringe. However, Glenn does not recognize Carol and picks her up King Kong-style, but Coulter is able to deliver the medicine with a stab at Glenn’s foot. Glenn carries Carol up the Boulder Dam, where Lindstrom is able to convince him to put her down. The the army fires at him with a rocket launcher and like the giant ape, he falls to his death.

Background & Analysis

The Amazing Colossal Man was born out of American International Pictures’ co-founder James Nicholson’s desire to ride the coat tails of the success of Universal’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review), released half a year prior to this film. He originally intended to – unofficially – adapt Homer Eon Flint’s pulp story The Nth Man from 1928, about a man who grows two miles tall. He set up Roger Corman as director and Corman’s frequent collaborator Charles Griffith as screenwriter. For reasons I have not been able to confirm, Corman left the project, and Bert I. Gordon offered his services. Griffith had written the script as a comedy, and according to Paul Blaisdell’s biographer Randy Palmer, it was “way out in left field”. Griffith agreed to rewrite the script, but apparently he and Gordon did not match, and he left the project after spending just one day with Gordon. Griffith later said that Gordon “[never could] stop looking over my shoulder”, and that he couldn’t work like that. Another Corman collaborator, Mark Hanna, was called in, and rewrote the script alongside Gordon. Apparently, SF staple George Worthing Yates also did some uncredited doctoring.

I haven’t found much information on prinicpal photography, but the budget was probably the usual AIP budget of around $100,000, and the film was probably shot in around a week or a week-and-a-half. Of course, the climax was filmed at the Boulder dam, and there’s a few shots from the Bronson Canyon. The film crew didn’t actually film in Las Vegas, but rather sent special effects man Paul Blaisdell to the city to take still pictures for the effects.

In 1955, Bert I. Gordon had made The Cyclops (review), which was released through in the late summer of 1957, and shares many similarities with The Amazing Colossal Man. The film follows a team of explorers who search for a missing husband, presumed dead in a remote area in South America. In fact, radiation has turned him and the rest of the wildlife gigantic, and has also messed up his brain and turned him into a growling monster. Apart from a facial deformity, the giant in The Cyclops is almost identical to Glenn in The Amazing Colossal Man. Both are stocky, bald men wearing loincloths. Both “disappear” from their wives and go through a transformation, which ultimately lead them to regress into a mental caveman state. Both films feature strong female leads who refuse to give up on their husbands and must fight red tape in order to help them.

Bert I. Gordon seems to have been endlessly fascinated with H.G. Wells‘ novel The Food of the Gods, a story which he later wound up adapting for film twice. Wells’ novel is both a satire and a socio-philosophical treatise on the subject of scale in society and social development. The first part of the book, which is the most famous, follows the developments of a new superfeed used for growing large chickens, which gets out into nature and starts transplanting itself through the food chain, creating monstrous wild animals. The second one deals with the social changes that take place after the superfeed has been turned into a supplement for humans, and people start growing out of control. And while The Amazing Colossal Man doesn’t follow the plot or even the themes of Wells’ book, its inspiration is undenialble. He has even snuck in a newscaster with a name sign that says “H. Wells”.

Considering Gordon’s obsession with gigantism, he seems to have had relatively little to actually say about it. Having now watched four of his movies involving gigantin monsters, two of them involving gigantic humans, I am struck by the fact of how little the films explore the social, societal, moral or philosophical aspects of gigantism, in stark contrast to Wells. The Amazing Colossal Man also primarily explores the immediate practical issues involved, namely housing, feeding and clothing a 60 foot man. The movie does have Glenn complaining and sulking about his predicament, but his lines could be more or less the same had he any other physical deformity that made his life difficult. The issue of a giant man living with a normal-sized woman is raised, but ever so briefly.

The science of the movie is laughable, but so is the premise, so this is predictable, and there is no need to go into details (such as the notion that the heart is “for all practicalities, a single cell”). More problematic is that the film’s logic is inexplicable. The entire film works its way up to providing a cure for Glenn’s predicament, and in the end the scientists work it out, and have plan for shrinking him back to normal. It even goes as far as delivering the first part of the cure to Glenn, but then just drop the whole issue. In the final scene, Dr. Lindstrom is able to talk Glenn into putting Carol down. Glenn is surrounded by soldiers and doesn’ appear to be an immediate threat to anyone or anything. But instead of fulfilling the plan to shrink him back to size, the military just decides to kill him, for no apparent reason, pulling the rug from under the feet of the entire plot — probably just for the sake of recreating its own King Kong moment.

At its core, this film has all the potential of The Incredible Shrinking Man. But as critic Bill Warren writes in his book Keep Watching the Skies!, it is “crass, heavy-handed and cumbersome, sentimental where it should be poignant, trite instead of familiar, prosaic where it should be inventive”. But then again, this is AIP and Bert I. Gordon, and not Universal and Jack Arnold. Roger Corman and Charles Griffith were occasionally able to turn out surprisingly poignant and intelligent movies from preposterous ideas, with little time of budget. But, alas, Mark Hanna was not the same caliber of screenwriter as Griffith, and Gordon certainly no Corman.

However, many have a soft spot for this movie. It’s certainly miles ahead of Gordon’s terrible King Dinosaur (1955, review), and it is a step up from The Cyclops. The story is well contained and Glenn Langan in the titular lead does well with the trite material he is given, even if he comes off as something of a cry-baby. Cathy Downs is also good as Carol, but just like in Gordon’s Beginning of the End, the strong female character of the beginning of the movie fades ever more into the background as the film progresses and the men take over.

As usual with Gordon, the special effects are a mixed bag. Gordon was intent on doing movies on a grand scale, with ambitious special effects that he couldn’t really afford. He did all his effects in-camera, saving time and money on the sort of compositing that other visual effects creators would have done, and unfortunately it often shows in the results, as thick matte lines, over- and underexposed elements and translucent monsters.

This time Gordon called on help from AIP’s monster maker extraordinaire, Paul Blaisdell. According to Randy Palmer’s biography, Blaisdell was excitied about the film, as it didn’t involve him making yet another monster costume that he would have to wear. Blaisdell, who was an experienced woodworker and model kit assembler, was tasked with creating the miniature props for Langan to interact with. These involved a drawer, a telephone, a barrel, a chair, and newspaper, a circus tent and some other bits and bobs. Blaisdell was also called upon to recreate famous landmarks from the Las Vegas Strip for Langan to interact with. These were mostly carved out of pine. The sequences where Glenn interacts with miniature props are the ones that work best in terms of special effects.

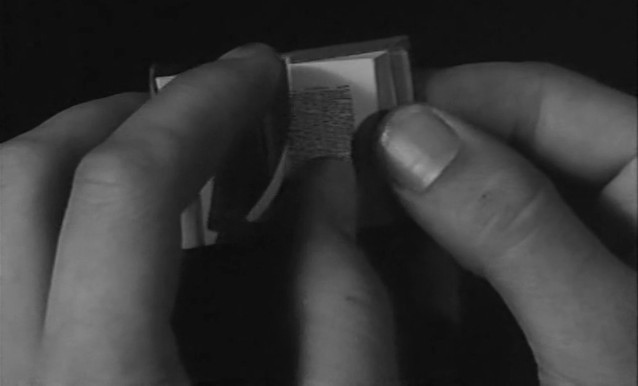

Paul Blaisdell also manufactured the giant syringe, which was well over 6 feet long. While it looks good as such, with Blaisdell’s usual attention to detail, it is also quite goofy. It is simply an ordinary syringe, complete with ringlets for the fingers and dosage markers. One would assume that if two top scientists were to design a medicine delivery system for a giant, they wouldn’t upscale a normal syringe, but make something less cumbersome. However, the syringe is somewhat iconic. In usual Blaisdell style, Paul made the syringe actually functionable. It was made out of plastic with a retractable metal tube for a needle, and it could hold and dispense a large amount of liquid. The Blaisdells kept the prop, and Bob Burns said that when he was over, they would sometimes play around with it like a giant super-soaker. Paul Blaisdell eventually donated it to Gordon, who kept a memorabilia collection from his films.

In one scene, Glenn walks behind famous Las Vegas buildings, which seem like front-projected photographs, and here the illusion is shattered by thick matte lines between him and the buildings. Other times he stands on the Strip itself and sort of interacts with people in front of the buildings. Of course, Gordon didn’t have the funds to close off the Las Vegas Strip for shooting. Instead he sent Blaisdell to the strip, who took still photos in the morning when it was still quiet. Gordon would then blow up these photos as back projection, and have extras act in front of them. As a third element, Glenn Langan was then matted into these shots. These superimpositions are often of bad quality, with Langan often either severely overexposed or translucent.

One shot that is actually impressive is the one in which Glenn is hit by the nuclear blast. There were three stages of makeup and wardrobe change, the final in which he appears completely flayed (good work here by veteran makeup artist Robert Schiffer). Instead of attempting cumersome in-camera dissolves or crossfades, Gordon cleverly edits the sequence with inserts between the stages, the result being that it actually looks as if Glenn is being stripped of his skin on-screen.

As always with both Gordon and Blaisdell, their wives, Flora Gordon and Jackie Blaisdell, were heavily involved with production, although they often went uncredited (as they were often not paid, and thus not officially on the production team). Here, Flora is credied as “assistant technical effects”, but she was usually also heavily involved in production management, catering, etc. Jackie Blaisdell was always on hand to help Paul with the production, and sometimes design, of the creatures and props for the movies, as was family friend Bob Burns, as he was also on The Amazing Colossal Man.

It is difficult to discern any actual theme or moral in The Amazing Colossal Man. According to Mark McGee’s book You Won’t Believe Your Eyes!, Gordon said: “I made The Amazing Colossal Man because I wanted to make a very human story.” And in a sense, it is the relationship between Glenn and Carol that carries this film, even if it is clumsily handled and ultimately doesn’t get any closure. As Gordon also said: “It was very difficult to show the warm, human relationship between the girl and the man she loved, grown to giant size, without becoming ludicrous.” As stated above, Gordon doesn’t delve deeper into any particular themes – this is the story of a man who grows to a giant size, period. Of course, the film taps into the underlying fear of atomic war in the 50s, but the reason for Glenn’s gigantism could be switched to anything else without it having the slightest impact on the movie. You can, if you want, see the movie as a treatise on the kind of themes of loss of self and loss of meaning in the post-war American society that The Incredible Shrinking Man dealt with. But I feel that these kind of back-mirror analyzes tack notions to the movie that are not present in the actual film, nor intended by its makers. It’s the kind of academic over-analyzing that turns the inclusion of a coffee cup in a movie into a comment on the slave trade. The inclusion of a miniature bible in The Amazing Colossal Man isn’t necessarily a comment on 50’s culture and religion, but rather the result of the fact that miniature bibles were available as cheap over-the-counter items in novelty shops – which is where Paul Blaisdell bought one.

As such, this is an entertaining movie, even if it drags both here and there. The script and dialogue are marginally better than in most Bert I. Gordon movies, but that bar is a low one. There is something rather endearing about this film, which really doesn’t include any villains or actual monsters, and is focused on the plight of a man who finds himself in a bizarre position. Glenn Langan is hampered by his dialogue, but gives a sincere and earnest performance, which easily wins you over. However, the segment in which Carol tries to solve the mystery of her disappeared husband is clearly the best, with nice, noirish photography and lighting by veteran Joseph Biroc, and an air of suspense and intrigue, thanks to the fact that the audience is just as much in the dark about Glenn’s fate as Carol. No special effects needed. AIP staple Albert Glasser once again provides a functioning, but routine score, illustrating in musical terms what is going on in the scenes – crashes for reveals and drama, thrilling for mystery scenes and sappy for emotional scenes.

Reception & Legacy

The Amazing Colossal Man was released in October, 1957 as the top of a double bill with British co-production Cat Girl, a psychological thriller, which was AIP’s first co-production with Anglo-Amalgated.

The Amazing Colossal Man generally recieved fair to good reviews. The New York Times cited an “imaginative story premise” and almost all trade papers praised the film’s special effects. Variety said that “technical departments are well handled”, while Harrison’s Reports called out “expert special effects work” and Film Bulletin wrote: “Special credit goes to the special effects department which [Gordon] uses in crackerjack fashsion”. Apparently 50’s critics wouldn’t have known sloppy effect work if it bit them in the behind. Harrison’s Reports also gave good notes to the actors, writing that “Glenn Langan […], being a competent actor, […] adds notes of real-life intensity to a largely hokum creation”, and that “Cathy Downs […] brings some nice touches of poignancy to the romantic interludes”. Motion Picture Exhibitor wrote that the “story holds average interest and the direction, production and acting are adequate”.

In his book Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren, as noted above, skewers the the film’s script, direction and special effects, but adds: “However, I still find The Amazing Colossal Man to be the most entertaining and watchable film ever made by Bert I. Gordon“. He continues: “Some of the dialogue is reasonable good, especially the scenes between Carol and the scientists […] The picture has good pace […] The best aspect of The Amazing Colossal Man is the acting. […] In the early scenes, before [Glenn] loses his mind completely and becomes a stock if somewhat unusual monster, Langan is good”. Mark McGee writes in You Won’t Believe Your Eyes! that “a movie aimed at youngsters shouldn’t seem as if it was written by one but that’s the problem with the scenario written by Mark Hanna and Bert Gordon“. But McGee also adds: “Dramatically speaking, it’s probably the best of Bert’s black-and-white movies”.

The Amazing Colossal Man has a 4.6/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on nearly 3,000 votes and a 2.8/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on a little over 1,000 votes. However, the film has a slightly higher 5.4/10 rating on critic aggregate Rotten Tomatoes. In cases when these kind of schlock movies have a higher critic than audience rating, the case is often that they have been featured on MST3K, which tends to result in low audience votes, particularly on IMDb. Such is the case with The Amazing Colossal Man.

In retrospect, the movie has gotten primarily positive reviews in major outlets. The New Yorker writes: “The pulp sublime reaches mad heights in this hectic, outrageous science-fiction drama”. TV Guide says: “One of the first atomic mutation horror films of the fifties, it is also one of the most absurdly entertaining. The scenes detailing Langan’s growth and his attack on Vegas are quite memorable.” AllMovie gives it 2/5 stars, but critic Bruce Eder strikes a more positive note (the ratings at the site are apparently not decided by the reviewer): “The Amazing Colossal Man benefits from some mostly passable (though occasionally ludicrous) special effects and a good central performance by Glenn Langan in the title role. There’s also solid supporting work by Cathy Downs, William Hudson, and Larry Thor […] If the movie has any serious flaw other than its low budget, it’s the slowing down of the action that takes place at the point where the giant disappears and a tiresome search begins, that eats up precious screen time with too many helicopter scenes that seem repetitive. But Gordon and the script just about make up for it with the shocking, painful denouement at Boulder Dam, where the military finally must take a hand.”

British Time Out called the movie “King Kong for the atomic age” and wrote: “A film of uncertain politics and scathing cynicism, in which a Bible is shown shrinking to unreadable size in the giant’s hand, and whose climax features an attack on Las Vegas, dream-city of the New America.” Christopher Stewardson at OurCulture Mag, who must be lauded for finding deeply philosophical themes in almost any no-budget cash grab, credits The Amazing Colossal Man with a “dissection of mankind’s changed position in a post-nuclear world”, noting that the “loss of self is the film’s key exploration”, articulating “the cultural and psychological development of a post-atomic world”. He concludes: “Even if one doesn’t read the film with such lofty implications, The Amazing Colossal Man still approaches its concepts with a maturity at odds with the expectations placed on it by decades of derision toward low-budget genre cinema.”

The above quotes do take the edge off Lisa Marie Bowman’s claim that this is the sort of film that “elitist critics love to criticize”. But I do concur with her conclusion at Through the Shattered Lens, perhaps more than with the high-falutin’ arguments of some of the above cited critics: “The Amazing Colossal Man is a 1950s B-movie and, when taken on those terms, it’s a lot of fun”.

The film was immensely popular on TV reruns and has become something of a cultural artefact, having been spoofed on both Saturday Night Live and Robot Chicken.

It was also a big success for AIP at the time of its release, prompting the studio to order a sequel from Bert Gordon. Gordon agreed, although in later interviews he has stated that he really didn’t want to do it, as he felt he had said what he wanted to in the original film. Glenn Langan declined to reprise the role, which instead went to Duncan Parkin, who had played the oversized menace in The Cyclops. To hide the fact that Glenn Manning wasn’t played by the same actor as in The Amazing Colossal Man, Gordon decided to give him a facial deformation almost identical to the one made for Parkin in The Cyclops. One wonders if they didn’t re-use some old facial appliances made for the former movie. The movie also spawned unrelated imitations such as Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958, review) and The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959).

Cast & Crew

Bert I. Gordon started to make home movies at the age of nine, and then moved into commercials before making his first film in 1954. Gordon became famous for his cheap visual effects, which he created himself along with his wife Flora, thus cutting costs on his productions. Unfortunately Gordon didn’t quite have the talent, the time, the money, nor the equipment to make good travelling mattes, which were needed for the giant creatures he inhabited his films with. Instead he often used high-contrast superimpositions, which sort of functioned as a poor man’s travelling mattes, but left fuzzy edges, resulted in severe matte lines and often turned whatever critter he was adding to the picture more or less transparent, sometimes with big holes in them where they reflected highlights. Another one of his favourite techniques was the age-old method of back projection, which, when done well, can work very effectively, stationary mattes and split-screen. Sometimes his effects came out quite nice, but more often than not they looked very cheap and amateurish.

Gordon often used his effects to portray gigantic critters or people, earning him the moniker “Mr. B.I.G.” (which of course was also an allusion to his initials), and is best known for films like The Amazing Colossal Man (1957, review), Attack of the Puppet People (1958, review), Earth vs. the Spider (1958, review), and his later, most successful film Empire of the Ants (1977), which was nominated as best picture at the first annual international fantasy film festival Fantasporto in Portugal in 1982. It lost to the Croatian movie The Redeemer. He became a prolific director for American International Pictures, churning out super-cheap sci-fi pictures in the late fifties, but left the company in 1960, working as an independent director/producer. Some of his later pictures did hold a slightly higher standard, but not all of them. But Gordon also branched out to other genres, like sword and sorcery, children’s movies, pirate films, witchcraft and horror films, a few murder thrillers and sexploitation movies. He kept on directing until the late eighties, although his films became less frequent, and then retired from the business after the movie Satan’s Princess (1989). He released an autobiography, and in an interview in 2015 said to have written a few screenplays. In 2011 he got a lifetime achievement award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films, which apparently prompted him to prove that he wasn’t quite dead yet. So in 2014, at 92 years old, he returned to the director’s chair after 26 years with the independently produced B horror film Secrets of a Psychopath, which had a limited theatrical release and was hardly noticed outside of genre circles. It received lukewarm reviews when it was released on DVD in 2015. Gorden passed away in March, 2023, at the very respectable age of 100.

The schlocky director has his defenders, such as Gary Westfahl, who in his Biographical Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Film states that although horribly flawed from an adult point of view, his films still had a huge impact on children when they were released. According to Westfahl, children could relate to the idea of being small in a world of giants, and, he posits, children didn’t understand enough to realise how dumb the dialogue and the plots of Gordon’s films were, neither did it matter to them that the effects were bad. Giant insects and people were inherently scary.

Westfahl also writes: ”Further, while his early films were usually threadbare – classic mom-and-pop operations, with Gordon and wife Flora Gordon chipping in for most of the offscreen labors – they were not slapdash; within the confines of his circumstances, Gordon usually tried to do good work, and if blessed with capable performers and a decent story, he might succeed. Only when Gordon attempted to cater to teenagers – an age group he manifestly did not understand – was an abysmal failure guaranteed.”

Screenwriter Mark Hanna made his Hollywood writing debut with Roger Corman’s western Gunslinger in 1956. Hanna was born in Rhode Island, Florida in 1917, the son of Lebanese immigrants. In his biography, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman at Schwab’s Drugstore, Hanna writes that he started out as an actor, doing theatre at the Little Theater in Jacksonville, Florida, one of the US’ oldest and, at the time, most well-regarded community theatres. After working, among other things, as a welder, he served as an aviation metalsmith in the US navy during WWII, after which he relocated to Hollywood, where he found work as a set builder and theatre director, and also acted on stage.

There is not much information on Hanna online, and his memoirs are an almost unreadable mess of anecdotes, mainly about his childhood and every single star he brushed shoulders with in Hollywood. After leafing through it I still can’t tell how Hanna got into movie acting or screenwriting. However, he did act in small bit-parts, mostly uncredited, in a good dozen movies between 1951 and 1954, before finding more success as a screenwriter. Between 1955 and 1958 Hanna wrote half a dozen films for AIP, most of them with Charles Griffith. However, The Amazing Colossal Man (1958) was co-written with director Bert I. Gordon and author/screenwriter George Worthing Yates. A commercial success, it was his second-to-last script for AIP. However, shortly after, a producer for Allied Artists commissioned Hanna to write a very unofficial sequel of sorts to that film — but about a giant woman. The result was Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, the movie which has become Hanna’s most lasting legacy. He had a small critical success with Raymie (1960), which won a prize at the Munich Children’s Film Festival. His credits become sporadic after 1961, with the decline of the classic B-movie, although he did still write a few low-budget films in the 70’s and 80’s. His last credit was the straight-to-video movie Star Portal (1997), which used the central premise of Not of This Earth. Hanna is credited for his original story.

Glenn Langan was at one time handpicked by 20th Century-Fox chief Darryl F. Zanuck as the next big star. Unfortunately Zanuck was notoriously bad at picking out future acting greats. Langan, born in 1917, got his early acting training in repertory companies in his hometown Denver, before trying his luck in New York, where he got good reviews of Broadway, leading to a contract with 20th Century-Fox. He had taken a stab at Hollywood in 1939, landing only bit-parts, but with the Fox contract in hand in 1942, things were looking up. He got a career boost in the mid-40s, when he started appearing in large supporting roles in many of the studio’s big pictures, like Margie (1946), Dragonwyck (1946), Forever Amber (1947) and The Snake Pit (1948). He commanded leads or co-leads in second features, like Fury at Furnace Creek (1948) and Treasure Island (1949). However, despite darkly handsome looks, a rugged charm and clear acting chops, Glenn Langan never became the star that Zanuck had slated him for. He was let go in 1949, and started freelancing in TV and B-movies, and despite the occasional B-movie lead, his fortunes were not improving. By the late 1950’s, little remained of his marquee draw. Playing the monster in an AIP movie was certainly not a feather in the cap for an actor trying to be taken seriously. Of course, today that is the role is remembered for. The Amazing Colossal Man proved something of a bookend for Langan’s acting career, as he gradually moved into real estate, as seems to have been the go-to profession for retired actors, for some reason. He appeared in a handful of movies after 1957, including Mutiny in Outer Space (1965), Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966) and The Andromeda Strain (1971).

Cathy Downs was a former model picked up by a major studio in the forties – in this case 20th Century-Fox. Fox did even groom her as a star at one point, and the highlight of her career was playing the title role in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946), but from there it all went downhill. However, she is something of a darling among friends of fifties science fiction, as she went on to play the leads in The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues (1955, review) The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and Missile to the Moon (1958, review).

William Hudson, playing Dr. Lindstrom, is another recognisable face for SF enthusiasts. Hudson had an unremarkable career as a bit-part player in the 40’s before entering TV in the 50’s. He gained some recognition with recurring roles in the popular TV shows Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954) and I Led 3 Lives (1954-1955), the latter a spy show starring SF legend Richard Carlson. He continued to combine small parts in movies with guest spots in TV shows up until the early 70s, but it was science fiction that gave him his biggest parts. He played the lead in The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957, review), and co-leads in The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and its semi-sequel Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). He also appeared in small roles in two family comedies about astronauts: Moon Pilot (1962) and The Reluctant Astronaut (1967), the latter starring Leslie Nielsen, long before his comedy career proper.

Larry Thor was a newscaster, announcer and drama actor in radio before entering the movie business in the early 50’s. Typecast as either newsman, police officer or military personnel, Thor played dignified character roles in close to 90 films or TV shows in the course of around 30 years. The rest of the cast is made up of seasoned bit-part and character actors, some of whom we have covered on this blog before, sucg as James Seay, Russ Bender and Edmund Cobb.

In a small role as a Sgt. Taylor we seeLyn Osborn, who played the co-lead in AIP’s SF comedy Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review). Osborn got his big break as he was cast as the co-lead of Cadet Happy on the TV show Space Patrol. Over the course of five years (1950-1955), over 1200 daily episodes were made, as well as one longer weekly, Saturday morning episode. The same cast and crew also produced a radio show. The hugely popular series was intended for children, but also retained a sizeable adult audience. Unsurprisingly, Lyn Osborn was in demand for science fiction movies after the show ended in 1955, and he appeared in such films as Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and The Cosmic Man (1959, review). Tragically, Osborn’s life was cut short, as he passed away during brain surgery due to a brain tumor in 1958.

Composer Albert Glasser was as prolific a composer, and worked as a sort of house composer for AIP.. IMDb credits him for over 100 film compositions and over 100 as part of the music department, and legend has it that there are several more out there that he is not credited for. His playing ground was strictly restricted to B movies, including The Neanderthal Man (1953), Indestructible Man (1956, review), Monster from Green Hell (1957, review), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and Earth vs the Spider (1958).

Cinematographer Joseph Biroc had previously worked on Frank Capra’s 1946 Christmas classic It’s A Wonderful Life. He had a prolific career, but got something of a second coming in the seventies and later with Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), Superman (1973) and The Towering Inferno (1974), where he photographed the action sequences and was awarded an Oscar for the effort. Biroc also became known as the cinematographer to go to for comedies, as he shot blockbusters like Blazing Saddles (1974), Airplane! (1980), and Airplane II: The Sequel (1982). He photographed a number of episodes of Adventures of Superman (1952-1958), as well as the sci-fi films Donovan’s Brain (1953, review), The Twonky (1953, review), Riders to the Stars (1954, review), The Unknown Terror (1957, review), and The Amazing Colossal Man (1957).

Sound editor Josef von Stroheim was none other than the son of demon director Erich von Stroheim. He went on to win a coule of Emmys for his work in TV.

Janne Wass

The Amazing Colossal Man. 1957, USA. Directed by Bert I. Gordon. Written by Mark Hanna, Bert I. Gordon, George Worthing Yates. Starring: Glenn Langan, Kathy Downs, William Hudson, Larry Thor, James Seay, Frank Jens, Russ Bender, Hank Patterson, Jimmy Cross. Music: Albert Glasser. Cinematography: Joseph Biroc. Editing. Ronald Sinclair. Production design: William Glasgow. Costume design: Bob Richards. Makeup: Robert Schiffer. Sound editor: Josef von Stroheim. Special effects: Bert I. Gordon, Norman Breedlove. Produced by Bert I. Gordon for Malibu Productions & AIP.

Leave a comment