A mother protects her teenage son, who has been turned into a murderous monster by the impact of a meteor. This poorly written 1957 indie weird western has little going for it, except some good monster makeup by Jack Pierce. 2/10

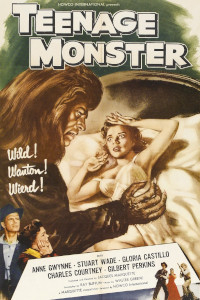

Teenage Monster. 1957, USA. Directed by Jacques Marquette. Written by Ray Buffum. Starring: Anne Gwynne, Gil Perkins, Gloria Castillo, Stuart Wade. Produced by Jacques Marquette. IMDb: 3.7/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Sometime back in the days of the wild west, a strange meteor strikes a poor gold miner Jim (Jim McCullough, Sr.) and his adolescent son Charles (Stephen Parker). Jim is struck dead, but Charles survives, although injured and affected by the impact. Fast-forward seven years, and we see that Charles (now played by Gil Perkins) has been turned into a monster by the strange meteor — he is now seven feet tall, covered in fur, with fangs and claws, and has an oddly affected, high-pitched, garbled speech which comes out mostly as grunts and growls. The impact seems to have stunted his mental growth, so his mind is still on the level of an adolescent, but with the hormonal angst and drive of a teenager, and the strength of a grizzly bear. His mother Ruth (Anne Gwynne) has wisely kept him hidden from the world, partly because he goes around killing people at random, and keeps toiling in her husband’s mine, hoping to strike the gold vein Jim always knew was there, and get rich.

Teenage Monster was yet another stab at the teenage monster genre which was so extremely popular in the late 50s. This 1957 production comes from producer/director Jacques Marquette and film distributor Howco. It was released as a double bill with Marquette’s The Brain from Planet Arous (review) in the fall of 1957.

Lo and behold, Ruth does strike gold, the thickest vein the town has seen since the Gold Rush. Now a rich woman, Ruth buys a house on the outskirts of the city, and Charles gets his own room where, of course, he is to stay hidden. But you know teenagers, and it isn’t long before cattle start dropping dead, and a few people as well. Charles also kidnaps pretty waitress Kathy (Gloria Castillo) and hides her in his closet when Ruth comes knocking. When Ruth discovers Kathy, she hires her as a companion for herself and Charles, at the same time buying Kathy’s silence.

Meanwhile the hunt for the mysterious monster is on, led by the town sheriff Bob (Stuart Wade), who also happens to be Ruth’s new sweetheart. This gets complicated when Bob starts coming over to Ruth’s house on a regular basis, seeing as Ruth literally has a monster in her closet.

Kathy also quickly realises that she can use Charles’ affection for her, wrapping him around her little finger. First she has Charles kill her obnoxious boyfriend, and when confronted by Ruth, she turns to blackmail. Of course, Ruth is now under her command, as Kathy could ruin her by revealing her secret. She has Ruth write a will which signs over her fortune to Kathy, and then tries to turn Charles against not only Bob (whom Charles already hates) but also his mother, for favouring Bob over her son. But will a mother’s love sway the beast, and is this the one time the monster isn’t shot and falls off a cliff in the end?

(Spoiler: no, it isn’t.)

Background & Analysis

In my previous review I wrote about the cult classic The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), produced by Jacques Marquette. Teenage Monster was its double bill pairing, and is a less remembered movie, and this time Marquette, a cameraman by trade, not only produced, but also directed. Again, the script was written by Ray Buffum from an idea by Marquette.

Marquette was a cameraman who struggled to advance to the rank of director of photography. In order to make it happen, he decided to begin producing his own films in 1957. He produced and filmed a small drag race movie Teenage Thunder for a low-budget distributing company called Howco International, and they went on to finance his second and third movie, The Brain from Planet Arous and Teenage Monster.

In an interview with Tom Weaver, Marquette says that very much like Roger Corman, he had spent enough time on movie sets that he saw how much money the studios were wasting on overhead costs and on paying ridiculously high salaries to actors, directors and other staff, rather than paying them scale (the union mininum): “I knew a hell of a lot of people in the business that were not working (and would like to keep working) that would be more than pleased to work for scale.”

Ray Buffum had written the script for Teenage Thunder, and it was directed by Paul Helmick, an assistant director hungry to climb the career ladder. According to Marquette, the film did well, but through “creative accounting” Howco kept all the profit. Howco then caughed up the dough for The Brain from Planet Arous and Teenage Monster, $57,000 each, which was a ridiculously low budget for a film. That both movies look as good as they do (The Brain from Planet Arous in particular) is a small miracle.

Whatever else there is to say about Teenage Monster, at least it has an interesting idea. Certainly, it wasn’t the first movie about someone hiding a monster in their attic, but few films had focused on a mother whose son is the monster. Throughout the film, Ruth keeps covering up her son’s murders, sheltering him from the world, while toiling in the mine in order to provide him with a better life. And of course, her love for her son is also what gets her in trouble, as the scheming Kathy quickly realises that she has Ruth by the short and curlies. The theme of a mother’s love forgiving all of her son’s trespassings, to the detriment of herself and her life underpins the entire story. Of course, she can’t marry the man she loves and move in together, as long as her son is around. And because he is still, and will probably always remain, at the mental capacity of a child, she can never give up the care of Charles.

Unfortunately, screenwriter Ray Buffum doesn’t delve deeper into this theme, and when he does touch upon it, he does so banally. Another problem is it’s difficult to build much sympathy for Charles and Ruth. The film sets out to portray Charles as the simpleton monster that is persecuted for being different. This worked so well in James Whale’s original Frankenstein (1931, review), partly because of the humanity that Boris Karloff gives the Creature, but also because Whale lets the film take its time to set up the character of the Creature. Teenage Monster clearly tries to emulate the same setup (a sort of Lennie from Of Mice and Men by way of Frankenstein), however, it goes about it in a backwards manner. In Frankenstein, the Creature had no urge or instinct to kill, but always did so out of self-preservation, by mistake or as calculated revenge for the wrongdoings levelled at it. The Creature was always clearly capable of discerning between right and wrong, and strove to choose right whenever it could. Charles, on the other hand, seems to have no moral qualms over killing, only over getting caught. We first meet teenage Charles strangling a man to death for no apparent reason, and another time he kills a man for not letting him pet his cows (and apparently kills the cows as well), and he seems happy to work as a hitman for Kathy. Ruth, on the other hand, seems to take the fact that Charles has probably killed dozens of people remarkably lightly, seemingly worrying more about Charles getting caught than him murdering hordes of innocent people from her own small town. This combination makes it very hard for the viewer to find much sympathy in their hearts for the two.

The ending of Teenage Monster is a mess. Kathy tries to convince Charles to kill Bob and Ruth as they have a meet-cute in the barn, but instead Charles turns on Kathy and drags her up a hill, apparently with the intention of throwing her off a cliff. This action is partly meant to redeem Charles, as he turns on the person that has been controlling him (Ms. Frankenstein, if you so wish). Kathy is clearly set up as the villain of the piece, but on the other hand, she was dragged into the whole business after being abducted and then bought off to keep quiet about the serial killer monster harboured by a millionaire widow. Why Charles feels the need to now suddenly throw his victims off a cliff, when strangulation has been his preferred method throughout the whole movie is also unclear. Of course, this is only to get him up to the cliff, so that he can tumble to his death, King Kong-style in the end. There is no closure or resolution to any of the themes in the movie. The ending goes like this:

Charles stands at the edge of the cliff, ready to throw Kathy to her death.

Ruth: “Charles, stop!”

Bob and the deputy start shooting. *BLAM BLAM*

Charles throws Kathy off the cliff.

Ruth: “Oh, my son!”

*BLAM BLAM*

Deputy: “What, that monster’s her son?”

*BLAM BLAM*

Charles is hit and falls to his death.

The End.

Another interesting thing about the script is that no attempt is even made to explain how the meteor (obviously done as a pair of sparklers shot out of focus) turned Charles into a monster. Was it a virus? Some alien entity entering Charles’ body? Radiation? Something that changed his metabolism? Alas, we have plenty of questions but no answers. The fact that the question isn’t even raised in the movie makes it very borderline science fiction.

Apart from Ruth, Charles and Kathy, the rest of the characters are really just placeholders. Stuart Wade was not the most charismatic or versatile actor to begin with, and as Sheriff Bob he doesn’t have much to work with, either. Veteran horror actress Anne Gwynne and relative newcomer Gloria Castillo carry the film, aided by seasoned stuntman/bit-part actor Gil Perkins. Perkins could have used some more direction, though. Perkins was also 50 years of age when he did this role, and even with the makeup on, it is difficult to buy him as a teenager.

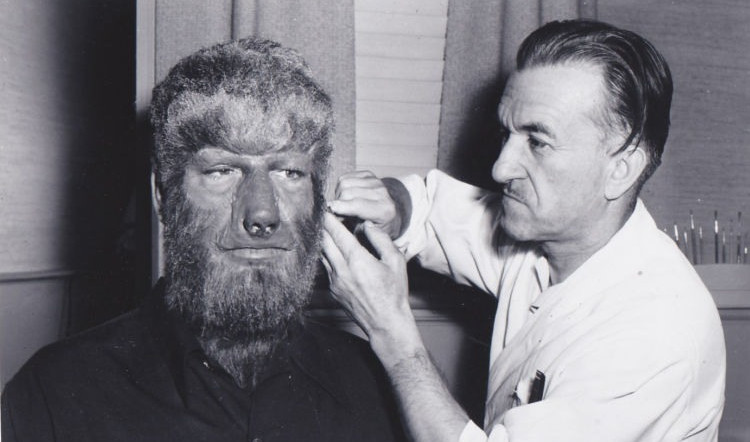

The monster makeup is surprisingly good for a film with this budget, and stands up to close scrutiny. However, it isn’t really surprising, as the makeup man hired for the film was Jack Pierce, the genius behind all of Universal’s classic monster makeups in the 30s and 40s.

Someone who was not a veteran was cinematographer Taylor Byars. Producer Jacques Marquette had also acted as cinematographer on The Brain from Planet Arous, but as he took over directorial duties on Teenage Monster, he decided to hire another DP. Marquette tells Tom Weaver in an interview that most of the movie was filmed at Melody Ranch, a western street used by Hollywood. The first day of shooting was supposed to be day-for-night photography, but apparently Byars wasn’t up to the task, and underexposed all film so that it became useless. This cut one whole day from the already tight eight-day shooting schedule, and Marquette bemoans that he often didn’t have time to do all the setups that he wanted to do, resulting in static cinematography.

The orchestral music by Walter Greene isn’t bad, but perfunctory, and serves primarily to heighten tension and drama during action and dramatic scenes.

Teenage Monster is far from the worst 50s monster/SF movie, and can be credited with some originality. However, it is ultimately a routine and forgettable entry with little to make it stand out.

Reception & Legacy

Teenage Monster was released in December, 1957, as a bottom bill to Marquette’s The Brain from Planet Arous. In the UK, it was outright banned, and wasn’t shown until 1995, when it was released on video.

The film received little attention upon release, and what it did get was negative. The Los Angeles Times said: “Story had potential […] But the idea was demolished by sleazy production, absurd casting”. Neal at Variety wrote: “This is a silly nonsense, an unworthy companion to the film with which it is being packaged”.

IMDb gives the movie a 3.7/10 audience rating, based on 400 votes, and it’s too obscure to have a consensus either on Letterboxd or Rotten Tomatoes. AllMovie gives it 1/5 stars.

DVD Savant Glenn Erickson writes: “The film is so primitive that none of the ugly subtext seems to matter. The same four interior sets carry the entire film, and exterior scenes frequently jump from day to night. Marquette’s action direction is terrible. The people on horseback ride as if they had their first lesson half an hour before. Plodding from event to event, the film barely holds our attention. Impossible characters defeat the actors”. Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV Reviews says: “It’s not the worst idea to have disgraced a 50s B science fiction film but Marquette’s lumpen direction, some very patchy performances and dreadful dialogue make it a lot more of a chore than it really should have been.”

Likewise, Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings notes that the idea holds promise. “Unfortunately, the movie fumbles the idea on practically every level; the direction by cinematrogapher Jacques R. Marquette shows a total lack of good judgment, the actors and actresses have no chemistry with each other, and the performances range from the merely adequate to the stunningly awful, and the script is full of howlingly bad lines.”

Cast & Crew

Brooklynite Jacques Marquette moved to Hollywood with his family when he was still a child in 1919, and from his early teens started working small jobs in the movie business, eventually becoming a cameraman in the 40s. As he explains to Tom Weaver, graduating from cameraman to director of photography in Hollywood was a bureaucratic process, as producers were obligied by union rules to choose from any and all cinematographers that were already available before “promoting” a cameraman to DP. That’s why he took matters into his own hands and in 1957 decided to become his own producer. He had been saving and raising a small amount of money for his own film, the drag race movie Teenage Thunder (1957), and somehow distribution company Howco got wind of it, and wanted to co-finance and distribute it. A minor hit, it prompted Howco to finance two more movies for Marquette Productions, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) and Teenage Monster (1957), the latter which he also directed.

The Brain from Planet Arous was directed by Nathan Juran (under the pseudonym Nathan Hertz), and apparently he and Marquette had a good working relationship, as Juran went on to direct the two next (and last) movies that Marquette produced: Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958, review) and Flight of the Lost Balloon (1961). The former, of course, has become a bona fide cult classic among SF fans. After this, Marquette had no need to produce his own films, as he was finally promoted to the status of director of photophy. He went on to steady work in the movies, and in his latter career, TV, and kept at until the late 80s. He also filmed the SF movies Last Woman on Earth (1960) and Varan the Unbelievable (1962), as well as a couple of SF TV movies and series.

Anne Gwynne was something of a horror staple, taking over the mantle of Universal’s scream queen after the departure of Evelyn Ankers. Gwynne was a former model who became a Universal staple in the late thirties and had a moderately successful career as leading lady or ”the other woman” in westerns and a few thrillers and horrors in the forties, and had a few guest spots on TV in the fifties. She played a substantial supporting role in the third Flash Gordon serial in 1940, had a brief appearance in an episode of the serial The Green Hornet (1942, review) and played the lead in the cheap horror sci-fi western Teenage Monster in 1958. Busty Gwynne was also a popular pin-up model among American soldiers in WWII.

Gil Perkins‘ life would probably be worthy of a film itself. He is most famous for donning the Creature makeup for Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943, review), where he doubled for Bela Lugosi whenever any physical action was needed, including the climactic battle between the Creature and the Wolf Man. Unfortunately, he didn’t get a chance for an actual on-screen credit as the Creature in 1944’s House of Frankenstein (1944, review), even though he provided stunts for the film. Instead, the role was played by another stuntman, Glenn Strange.

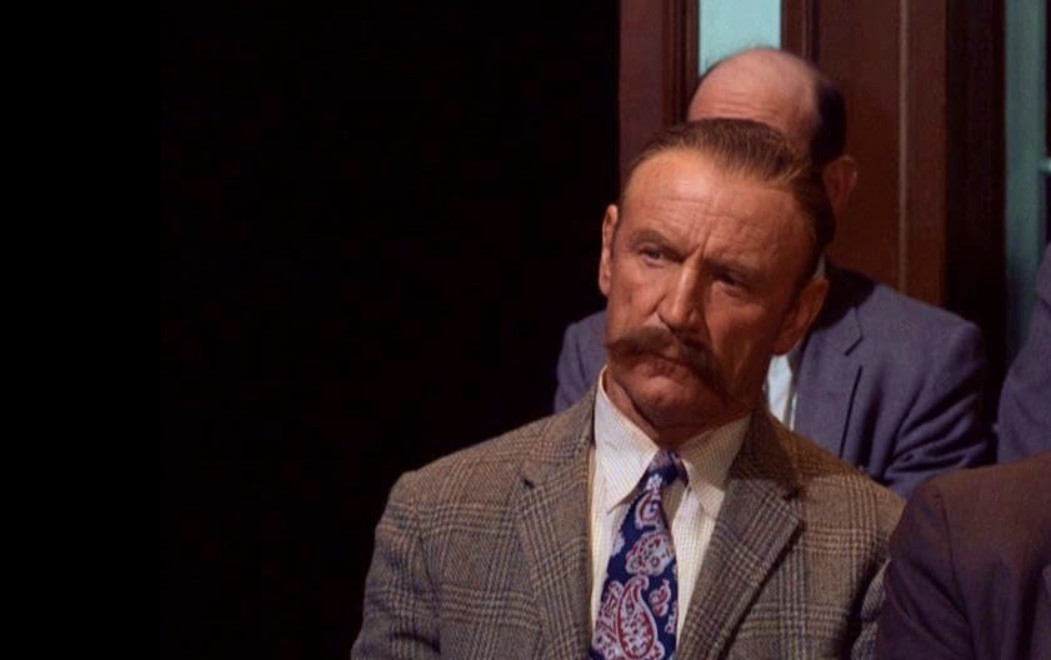

Born in 1907 in Australia, Gilbert Perkins more or less ran away from home as a teenager, as he mustered on a Norwegian freighter and travelled the world, eventually following his dreams to Hollywood in the late 1920s. His athleticism quickly got him stunt work, but his heritage also aided him in getting speaking parts. As Hollywood rapidly swithed from silent film to sound, many foreign stars of the screen found themselves struggling because of their thick actors. One group, however, saw their fortunes improving significantly — those who could manage a British accent. By slightly adjusting his Australian accent, Perkins passed as British well enough for American audiences, at least in small parts. While he mostly played uncredited bit-parts, the difference in salary between a silent and a speaking part was significant. Throughout his career, Perkins often played brawlers, henchmen, police officers, military personnel, and bouncers, and other parts that required stunt work and athleticism.

Still it was as a stuntman that he got most of his screen time. In 1933, he doubled for lead actor Bruce Cabot in King Kong (1933, review), then provided stunts in other big-budget classics like Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and The Aventures of Robin Hood (1938), before his first turn as a monster in 1941, doubling for Spencer Tracy in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941, review). The same year, he became the stunt double for William Boyd, and subsequently played Hopalong Cassidy in a multitude of films throughout the 40s. And in 1954, he was Kirk Douglas‘ stunt double in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (review). With his experience, he also started working occasionally as stunt coordinator. He turned in work as either stuntman, actor, or both, in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953), Valley of the Dragons (1961), The Silencers (1966) and Batman: The Movie (1966). In the late 60s he turned up in a number of science fiction TV shows, including Get Smart and Batman, in which he appeared in 3 and 5 episodes, respectively. He popped up as a slave in the 1968 Star Trek episode “Bread and Circuses”. Perkins was one of the co-financers of Jacques Marquette’s low-budget movies, released through Howco, in 1957: Teenage Thunder, The Brain from Planet Arous and Teenage Monster, the latter of which provided him with the only starring role of his career.

Gloria Castillo, as the scheming Kathy, was cast for her reputation as the hot ticket with teenage audiences. Castillo, in her 15 minutes of fame, appeared in leads or co-leads in a handful of teenage movies in the late 50’s, like Runaway Daughters (1956), Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review), Teenage Monster (1957) and Reform School Girl (1957). She ping-ponged between these leads in no-budget teen fillms, TV and a few bit-parts in bigger films. She dropped out of acting in 1967 and had some success with her and her husband’s women’s clothing company.

Stuart Wade as the romantic lead in Teenage Monster, the sheriff, is the kind of actor that does not have a Wikipedia entry or even a profile picture on IMDb. Wade’s background was primarily in music, he was a band leader and singer, you can hear his lovely baritone here, for example. Wade splashed onto the Hollywood scene, cast as the made lead in his very first movie role in 1954. Unfortunately, it was a lead in the first evet movie Roger Corman produced, Monster from the Ocean Floor (review), allegedly with a budget of $19,000. Wade had another lead in Teenage Monster (1958), but most of his 20 credits are for TV work.

Makeup artist Jack Pierce, of course, is famous for having created the makup for Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, Jr., Bela Lugosi and many others during the golden era of Universal’s monster movies in the 30’s and 40’s. Pierce can almost be said to be single-handedly responsible for the modern image of Frankenstein’s Creature, the Mummy, the Wolf Man and Dracula. However, Pierce also had a reputation of being a perfectionist, making his actors suffer long and painful hours in the makeup chair, and for being a cantankerous self-styled “genius” who wanted to do things his way or no way, and was prone to getting into spats with colleagues. When Bud Westmore took over as the head of Universal’s makeup department in the late 50s, Pierce found that no other studio would hire him as department head, and he instead struck out as a freelancer, working mainly on B-movies, such as The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), Teenage Monster (1957), The Amazing Transparent Man (1960), Beyond the Time Barrier (1960) and The Creation of the Humanoids (1962). He rounded out is illustrous career as the resident makeup artist for the family comedy TV series Mister Ed (1962-1964), which must have felt like a rather disappointing swan song for the great master, even if it put food on the table.

Janne Wass

Teenage Monster. 1957, USA. Directed by Jacques Marquette. Written by Ray Buffum. Starring: Anne Gwynne, Gil Perkins, Gloria Castillo, Stuart Wade, Chuck Courtney, Norman Leavitt, Gabe Mooradian, Jim McCullough, Sr., Frank Davis, Arthur Berkeley. Music: Walter Greene. Cinematography: Taylor Byars. Editing: Irving Schoenberg. Makeup: Jack Pierce. Produced by Jacques Marquette for Marquette Productions & Howco International.

Leave a comment