Scientists battle giant prehistoric scorpions in Mexico in this 1957 Warner low-budget production. Willis O’Brien’s and Pete Peterson’s magnificent stop motion sequences balance out a poor and drawn-out script. 6/10

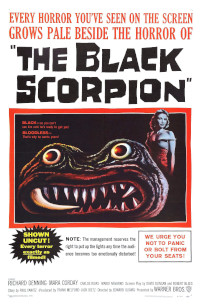

The Black Scorpion. 1957, USA. Directed by Edward Ludwig. Written by David Duncan, Robert Blees & Paul Yawitz. Starring: Richard Denning, Mara Corday, Carlos Rivas. Produced by Jack Dietz & Frank Melford. IMDb; 5.4/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 5.3/10. Metacritic: N/A.

Geologists Hank (Richard Denning) and Ramos (Carlos Rivas) investigate a devastating volcanic eruption in Mexico by jeep. On their way to the small town of Santa Mira, they come upon a gas station that has been demolished and a police car that has been torn up “like it was paper”. One of the police officers is found dead without an apparent cause of death — but with an expression of horror on his face. But what could have caused this destruction?

Well the audience doesn’t have to guess, because the title of this 1957 movie is The Black Scorpion, and the beginning is an almost complete copy of Them! (1954, review), the giant ant movie from a few years before. The Black Scorpion is best known for being the last movie that Willis O’Brien provided animation for. The movie was produced by Warner Bros., the same studio that made Them!, albeit on a substantially lower budget. In order to make the the buck stretch as long as possible, producers Jack Dietz and Frank Melford decided to take the production to Mexico, where all live-action footage was filmed.

Hank and Ramos make it throgh the devastation to Santa Mira, where they are greeted by the local priest, Father Delgado (Pedro Galvan) and young boy Juanito (Mario Navarro), who immediately takes a liking to Hank. (Here, they also bring a small baby whom they found among the ruins of the gas station.) Delgado tells the two geologists that both cattle and people have gone mysteriously missing, and the town is dealing with both the devastation of the volcano and the belief that some mythological monster is on a killing spree.

Hank and Ramos strike up a friendship with rancher Teresa Alvarez (Mara Corday), and between her and Hank the friendship isn’t merely platonic. They also find one of the victims of the “monster”, as well as a small live(!) scorpion trapped in thousands of years old volcanic rock. They get help from Mexico City, when the famous Dr. Velasco (Carlos Musquiz) comes down to analyze the venom found in the victim, and concludes it is scorpion venom. At the same time, a giant scorpion is seen outside of Santa Mira, killing a linesman. Later, a swarm of big scorpions all but lay waste to Santa Mira. Bullets won’t harm them.

So, our heroes form a strike team and head to the mountains in order to find the scorpions’ nest and gas them to death. Hank and Ramos descent into a super-deep, super-large cave, where they find dozens of scorpions, a giant tentacled worm and a giant spider. They take pictures and walk around, until they realize Juanito has snuck with them in the metal basket that has been lowered into the cave, along with the gas. Naturally, he gets in trouble, and the three barely make it out alive. Well back on the ground, the team decide to blow up the mountainside and trap the scorpions inside, not unlike the heroic team in Them!, torching the hell out of the anthill in the desert. And if you’ve seen Them!, then you know that this won’t be the end of the scorpions, either.

No, some stragglers have made it out through the tunnels and derail a train headed for Mexico City. The smaller scorpions are devoured by “the granddaddy”, a truly gigantic creature, which now steers toward the big city. Working frantically to come up with a weapon, our team develop a giant, rocket-launched taser, and lure the scorpion into a final battle with the army in the city’s arena.

Background & Analysis

There’s some confusion over the origins of this film. However, what we do know is that it all began in 1953, when independent producers Jack Dietz and Frank Melford sold Warner Brothers a low-budget film called The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (review), which included stop-motion animation of a giant dinosaur wreaking havoc on New York City. The animation was done by Ray Harryhausen, a protegé of Willis O’Brien, who famously created the effects for The Lost World (1925, review) and King Kong (1933, review). The movie was a surprise hit, and inspired a whole subgenre of monster film. Wanting to cash in on the success a second time, Warner quickly produced their own giant monster movie, this time about giant ants attacking Los Angeles, and on a big(ish) budget. As Them! was originally supposed to be made in 3D, which at the time didn’t lend itself well to visual effects (because of the optical printing process required), all ant effects had to be done in-camera, with models and live-action puppets, rather than as stop-motion effects. Them! became, if possible, an even bigger hit than The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, despite no 3D, no colour and a slashed budget, and is today considered one of the best SF movies of the 50s.

Dietz and Melford weren’t involved in the making of Them!, and probably thought they were entitled to a piece of the pie, as it was their movie that started it all. In my understanding, according to some sources, Dietz and Melford approached Warner with a short test footage reel of giant scorpions attacking a truck, animated by Willis O’Brien and his assistant animator Pete Peterson. This test was supposedly a proof of intent, and a way to show Warner Bros. that giant critters look so much better when they are stop motion animated than as giant, clumsy models. There’s been much speculation about this supposed test reel, but as far as I can tell, no-one has actually been able to comfirm that it ever existed or that it was, as some argue, the starting shot of the movie. On the other hand, I haven’t seen anyone debunk it, either.

Paul Yawitz gets a story credit for The Black Scorpion – which is surprising, as Yawitz was best known for writing low-budget westerns and slapstick comedy. The screenplay was written by David Duncan and Robert Blees, two writers who could turn out fair scripts on a good day – Duncan wrote the script for George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960). Apparently, this wasn’t a good day. As my plot description above illustrates, The Black Scorpion seems like Warner’s deliberate attempt to recreate Them!. The plot ticks almost all the boxes: from the protagonists coming over a mysteriously wrecked vehicle and a destroyed gas station and picking up a surviving child, to the strong female character, the introduction of an older guru, and so forth. In this case, however, the child found is of no consequence to the plot, and the strong female character gets absolutely nothing to do but stand on the sidelines. Like Them!, the film tries to build mystery around the menace by not revealing the monster until midway through. This worked well in Them!, where it really was a mystery, but this film’s title is The Black Scorpion, so there’s not much mystery surrounding the culprit.

The film commits the same cardinal sin as so many other Them! ripoffs in the late 50’s: It has the protagonists spend way too much time trying to figure out what is doing all the killing and destroying, which doesn’t amount to mystery and excitement for the audience, because we already know that we are dealing with a deadly mantis or a black scorpion. Watching the protagonists trying to catch up with the audience seldom amounts to a good movie. At some point in this movie, there is even talk of some “devil bull” of Mexican superstition. Now, this might have worked, had the film not advertised its monster on the poster. It doesn’t help that the film pads out its running time with a tedious by-the-numbers romance that we are not so much shown as told about. Apparently the screenwriters were no good with romance, so we are simply informed that Hank and Teresa are suddenly an item. Not that this has any bearing on the plot, it’s just that producers of these films all thought they needed to have a romance. While they were copying Them!, the screenwriters might have looked at the original movie and noticed that Them! actually doesn’t have a romantic subplot.

The characters are also, as is customary in these films, boring, and get by mainly on the strength of their actors. Richard Denning was an actor with an admittedly limited range, but with a charisma and charm that always livened up any movie he was in. He was also an actor who always gave his all, even in minor pictures. The same thing could be said of Mara Corday. Carlos Rivas is no Shakespearan actor, but he comes off well in The Black Scorpion, striking up a good buddy chemistry with Denning (even if they apparently didn’t get along too well off-screen). Pedro Galvan as the padre is fine in his role, and the breakout character of the eccentric local scientist, played by comedic actor Pascual García Peña, is fun, but only seen briefly. Carlos Musquiz as the guru scientist does what is expected of him. The rest of the all-Mexican cast all seem stiff and amateurish — perhaps because they were acting in a foreign language, and perhaps because some of them were actually amateurs.

A final annoying aspect of this movie is the ever-present character of Juanito. Mario Navarro isn’t a bad child actor per se, but he is written as one of these super-annoying, over-enthusiastic kid characters that shout all their lines and seems to adopt the adult main character as some sort of father figure for no apparent reason. The screenwriters fail to give him any story function, and simply operate on the faulty assumption that kids go to the movies to watch kids on the screen.

Edward Ludwig’s stiff direction doesn’t help. In several scenes minor characters simply stand on their X, speak their lines stiffly and walk out of frame. This was probably partly due to time restraints. So much time and effort probably went to the numerous special effects scenes, that dramatic scenes had to be done quickly and with as few takes as possible.

All that said, The Black Scorpion is without doubt one of the better low-budget science fiction films of the late 50s — and that is all thanks to the excellent, exciting and dynamic animation by Willis O’Brien and Pete Peterson. The stop motion animation is superb, with at least three smaller and one large scorpion milling about the screen, lunging, stinging, derailing trains, cutting people in half, flinging cars tanks around like they were toys, snatching helicopters out of the air and slam-dunking them on the ground. There are three major animation set piece of the film. The first is a stunning cave sequence with scorpions battling a giant worm, and then each other (there’s some thing about the scorpions becoming mad when they smell blood), a trap door spider chasing Juanito and finally the scorpions attacking Hank and Ramos. The second one a terrific scene in which the granddady scorpion derails a passenger train and the scorpions start eating the passengers, and the third is the final climactic battle at the stadium, which is absolutely awesome. This is some of the best animation seen in a 50’s SF movie.

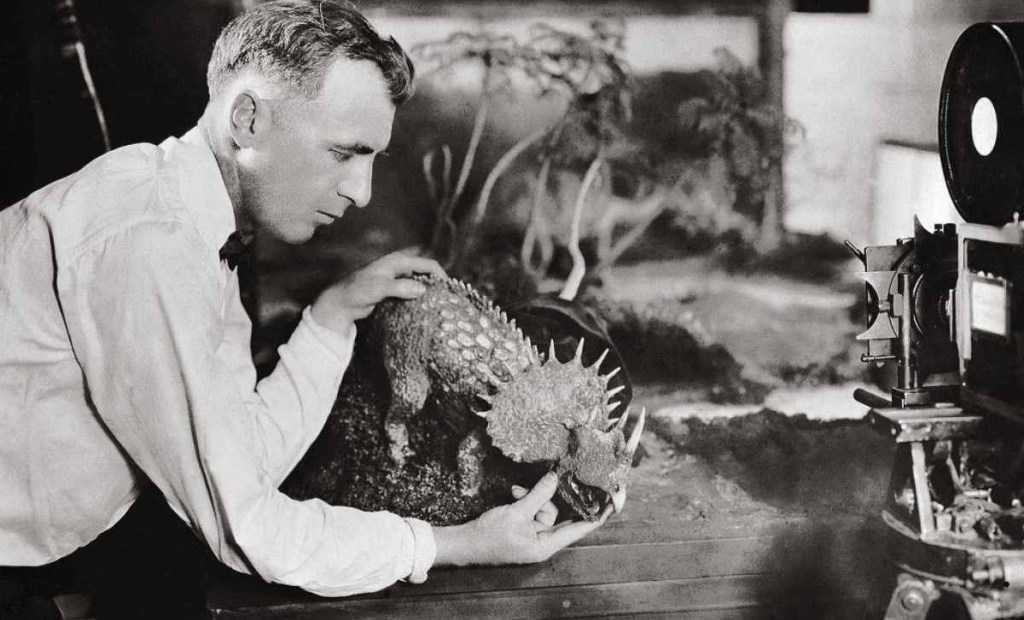

Willis O’Brien is credited as “animation supervisor” and Peterson is credited as animator. This has led to speculation that it was Peterson who did all the actual work, however collector and one-time prop and special effects man Bob Burns has talked about witnessing O’Brien hard at work with the animation for the movie. O’Brien was 71 years old when he made The Black Scorpion, and with the minuscule budget of the film, he would have had to turn out a huge amount of animation in a very short time. Even in his prime, this would have been a challenge, and old age probably meant he wasn’t able to work as fast or as much as he once could. Pete Peterson had been O’Brien’s assistant for decades, and he probably took on the lion’s share of the actual animation, while O’Brien probably handled camera and sets to a larger degree. However, Pete Peterson had once harboured dreams of setting out on a career as an animator in his own right, but these dreams were brought to a halt when he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. This means that this amazing footage, requiring long working hours and exact fine motor skills was turned out by a septagenarian and a person suffering from a muscle deficiancy, making the end result all the more impressing.

The low budget unfortunately shows. Several scenes are used repeatedly, sometimes flipped to disguise them. Near the film’s ending, before the climactic battle, there are a few scenes with the giant scorpion rampaging through the streets of Mexico City. Except the scorpion is just a black scorpion-shaped hole. Special effects aficionados will quickly recognise this black hole as an unfinished traveling matte shot. Without getting too technical, the way these matte shots were made required several optical printing passes, one of which was an intermediate stage, in which the image that was being matted into the background would only have been represented by a “black hole”, or unexposed film, on the background footage, after which the actual image of, in this case a giant scorpion, would be added in the next pass. In this case, one of the people doing the compositing has explained that the money simply ran out, and Warner wouldn’t pay for having the scene finished, so it was released as was.

One thing that gets a lot of flack is a so-called “hero head” of the scorpion, that gets shown a lot. This is large, live-action puppet head that gets shown in all the sequences where the scorpions appear, which has moving mandibles, pulsating eyes and that drools incredible amounts of slime. It is utterly revolting, to the point, some claim, of being ridiculous. Apparently, the film team didn’t spend much time with the head, as it reuses two or maybe three shots of the head — I haven’t counted, but at least 30 times during the movie. The head is actually quite well made, and it is approriately ugly. I don’t find the actual design or puppet as bad as a lot of critics do, and actually think it is rather cool. However, I agree that at the rate that the few shots get reused, it crosses over to silliness.

I haven’t found any information on who actually designed the thing, but it was put together and was operated by the brilliant Wah Chang, who, among other things, did a lot of the iconic design on the original Star Trek series. One funny story, a bit of a film cross-over, is relayed by Bob Burns in an interview. Turns out that AIP’s monster maker Paul Blaisdell and his assistant Bob Burns were sharing a workshop with Cheng while they were working on the effects of AIP’s comedy Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review). In the film, the aliens kill by injecting their victims with alcohol that they shoot from their claws. For the effect, Blaisdell and Burns used ear syringes to squirt the liquid. Wah Cheng had the exact same idea for producing the drool from the scorpion head, but on the day he was putting the effect together, he had forgotten to bring syringes. As he noticed that Burns and Blaisdell were working with ear syringes, he walked up to them and told them he was working on a film with Willis O’Brien and asked if they could possible let him use one of the syringes. When Blaisdell and Burns heard the name Willis O’Brien, they were quite enthusiastic to help out.

One of the talking points of The Black Scorpion is the cave scene, and its supposed connection to the legendary “spider pit sequence” that was cut out from the original King Kong movie. There have been claims that the trap door spider in The Black Scorpion was a leftover model from the King Kong spider pit scene, or that the cave scene of The Black Scorpion would have reused actual footage from the scene. The latter has been debunked, but there are still those who claim that the spider model is the one from King Kong. I do not know either way, and frankly do not care. But in any case, there is such a discussion still going on between aficionados.

In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, Richard Denning complains about the conditions during filming. He said they had an outhouse loo, which was horrible, and says that he got sick during the production because of the water. Mara Corday tells Weaver that Denning only had his self to blame for drinking the water and not listening to advice. She says that the outhouse loo was situated at the edge of the volcano, where they filmed for a couple of days, and that she deliberately stayed away from it — again, Denning didn’t. In fact, Corday says that they stayed at a wonderful hotel, where they bumped into Anthony Quinn, Ray Milland and Debra Paget, who were also there making a movie.

Once again, as is often the case with late 50’s monster movies, this is not a film in which one will find much intellectual content. There are no cold war references to mine here, in fact this is one of the very few monster movies in which radiation isn’t even an issue — the giant scorpions are just giant, prehistoric scorpions that have somehow survived under the volcano. It’s a cash-grab ripoff designed to put seats in theatres and entertain kids. And that it did do. But it is also one of the better made, and more entertaining examples of late 50’s SF cash grabs. With the exception of the “black hole scorpion”, the matte shots and composits are very well done, with the exception of a few fuzzy rear screen projections. The animated action is superb, and the film is quite well edited, disregarding the many reused shots. The lead actors all perform well, given the poor quality of the script, the flat characters and the ridiculous dialogue.

It’s a shame that Warner didn’t see clearly enough to lavish The Black Scorpion with even $100,000 more in budget. They had a crack special effects team, a fair idea and good actors. Had the studio excised a little more quality control over the script, added a few more days of principal photography and given the special effects team a few more days of work, they might have had a really good film on their hands. As it stands, The Black Scorpion almost feels like a mashup of two different films. The animation seems to belong in a costly blockbuster movie, while the live-action sequences remind the audiences that it is watching a super-cheap exploitation film. It’s at the same time a riveting and excrutiating film to watch.

Reception & Legacy

The Black Scorpion opened in October, 1957, and as a major studio film, had a worldwide distribution over the next two years.

The film got middling reviews in the trade press. Variety wrote: “Somewhat haphazardly put together, it still manages some high degree of excitement and a chilling windup. Special effects are particularly well handled. […] Denning capably handles his role, as does Rivas, and Mara Corday“. Harrison’s Reports called it a “fairly good melodrama of its kind, but doesn’t rise above the level of program fare, and the running time is far too long. […] There is nothing unusual about the story, which follows a familiar pattern, but the special effects work is better than average.” The Motion Picture Exhibitor said the film was “no better or worse than other horror entries featuring giant insects as the menace. The special effects are the thing”. The New York Times liked the Mexican locations and some of the “technical fakery” but considered the film “strictly standard” with forgettable human plot elements.

The Black Scorpion was riffed on MST3K in 1990. Its inclusion on the show, which focuses on riffing bad movies, has been criticised, as many fans feel that the film is not as bad as to be lumped together with other films feautured in the program. Paste writer Jim Vogel, for example, stated that the film is “a little tedious, sure, but the film actually sports some pretty damn cool-looking stop-motion animation special effects”.

Today, the film has a 5.4/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on over 3,000 votes, and a 2.9/5 star rating on Letterboxd, based on 2,000 votes. It has a 5.3/10 critic consensus, and a good 67% Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

I love Christopher Stewardson at OurCulture Mag, constantly giving out top-notch ratings for extremely flawed 50s films. Stewardson lavished The Black Scorpion with 4/5 stars: “The Black Scorpion is a marvellous film. It steadily builds tension until its scorpions menace the characters and the audience. The special effects are thrilling and highly effective, giving character to the awesome arachnids. The film’s cast are charismatic and likeable, even if the archaic notions of the 1950s occasionally creep into their dialogue.”

Richard Scheib at Moria is in unusually sprightly form, awarding 3/5 stars to the movie: “Directorially and in terms of plot, The Black Scorpion is routine. The plotting, the romance, the photography, the acting is completely standard and undistinguished 1950s B monster movie formula. What does stand The Black Scorpion above the routine are the scorpion attack set-pieces. […] The difference between The Black Scorpion and the other films, which mostly used men in rubber suits or optically enlarged bugs, is immediately apparent. With Willis O’Brien at work here, and even though he is operating on an impoverished budget, the creatures are invested with enormous detail and character that most of the other monster movies of the era lack.”

DVD Savant Glenn Erickson isn’t as impressed: “Spectacular special effects can’t hide a bad script, and are almost ruined anyway by some editorial monkeying with a ridiculous puppet-head that screams at the camera every six seconds or so.

Cast & Crew

Director Edward Ludwig was born in 1889 (as Isidor Litwack) near Odessa, current-day Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. His family emigrated to the US via Canada when he was still a child. He reportedly entered the movie business as an actor in the 1910s, but started working as a scenarist and short movie director in the early 20s, then working under the moniker Edward Luddy. By the early 30s he had graduated to feature films. Ludwig was consigned to programmatic B-movies for his entire career, and apart from The Black Scorpion, he is best known for helming a handful of John Wayne movies, including The Fighting Seebees (1944), Wake of the Red Witch (1948) and Big Jim McLain (1952), reminding us that the Duke actually did much more than westerns. He was renowned for having a knack for action, which may be the reason he was assigned by Warner to direct The Black Scorpion. However, he was somewhat out of his element, as this was his only foray into SF or horror. Mara Corday describes him as belonging to “the old school of screamers”, which didn’t endear him to the Mexican crew.

Screenwriter David Duncan is of considerable interest to science fiction fans. After working for 10 years in government, he began writing professionally. He wrote over a dozen novels between 1944. In the mid-to-late 50s, he wrote a handful of science fiction novels, including Dark Dominion (1954), Beyond Eden (1955) and Occam’s Razor (1957). There are differing opinions on his writing. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction states that “Those who rediscover him will find his work quietly eloquent, inherently memorable, worth remarking upon”. SF critic Joachim Boaz, on the other hand, states that Dark Dominion “is characterized by an incredibly painful strain of melodrama even for the 50s, downright preposterous science”.

Duncan was also one of the more prolific Hollywood SF screenwriters over the 50s and 60s, penning or co-penning scripts for no less than seven science fiction movies. He wrote the script for the Enlish-language version of Rodan (1956, review), and the first script treatment for The Monster that Challenged the World (1957, review). He then co-wrote the script for The Black Scorpion, and wrote Jack Arnold’s Monster on the Campus (1958, review), before penning several episodes of the well-regarded TV show Men Into Space (1959-1960). He is best known today for adapting H.G. Wells’ novel The Time Machine (1960) for the screen for George Pal — a film that is still considered as one of the very bestWells adaptations in history. He then wote the less lauded Leech Woman (1960) and is given credit for the adaptation of the Jerome Bixby/Otto Klement story which serves as the basis for another big-budget film, Fantastic Voyage (1966).

Robert Blees was a prolific and respected screen- and television writer, best known for penning the scripts for Jack Arnold’s The Glass Web (1953) and High School Confidential (1958), Douglas Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954) and Robert Aldrich’s Autumn Leaves (1956). He also co-wrote such diverse SF movies as The Black Scorpion (1957), Byron Haskin’s Jules Verne adaptation From the Earth to the Moon (1958, review), the much-maligned Frogs (1972) and Curse of the Black Widow (1977). Blees also penned several episodes of the TV show Project U.F.O. (1978-1979), and both wrote for and produced several other popular TV shows. He sat on the board of both the Writers Guild and the Producers Guild of America, and served on the board of the Motion Pictures & Television Fund for 30 years.

Richard Denning had a background as a “working actor” in Paramount’s stock company in the early 40s, where he played lesser roles in big films and bigger roles in lesser films, and had a number of B-movie leads under his vest when his career was put on hold during WWII. But he bounced back well as a freelancer, now married to Universal’s scream queen Evelyn Ankers. His first science fiction movie was a gadget macguffin reel called Television Spy (1939) and the next was Unknown Island (1948, review). However, he became a minor star in 1952 when he starred in the titular lead of the television series Mr. and Mrs. North, about a married couple solving crimes as amateur sleuths. The show was a success and ran for two seasons. However, he is perhaps best known for his role as second male lead in Universal’s SF classic Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), playing opposite Richard Carlson and Julie Adams.

Denning would go on to more television fame in the Australian series The Flying Doctor (1959), as detective Michael Shane (1960-1961) and as father Steve Scott on the family sitcom Karen (1964-1965). Just as he was about to retire in Hawaii in 1968, he was lured into playing the role he is perhaps most famous for, the mayor in Hawaii Five-O (1968-1980). He was also a known voice on the radio, after having starred opposite Lucille Ball in the program My Favourite Husband (1948-1951). But in between TV roles, there was a period when Richard Denning was the hottest science fiction star in Hollywood, as he racked up lead after lead in sci-fi movies, starting with Universal’s smash hit Creature from the Black Lagoon. He followed up with Target Earth (1954, review), Creature with the Atom Brain (1955, review) Day the World Ended (1955, review), The Black Scorpion (1957) and finally Twice-Told Tales (1963).

Actress and model Mara Corday was born Marilyn Watts, but changed her name because she thought her birth name wasn’t exotic enough for show business. All through her childhood she wanted to be in show business, and was eagerly spurred on by her mother, who even faked her birth certificate when she was seventeen so that she could get a job as a chorus girl – she had to be eighteen to get the gig. Talking to Tom Weaver, Corday says she has no regrets of using cheesecake photography as a springboard for her film carer (as late as 1958 she was Miss October in Playboy – you can check out her Playboy pictures here, no nudity). On the contrary, she was disappointed that Universal never used her sex appeal in any of the films she was in – instead they covered her up. Even in the last part of Tarantula (1956, review), when she is running from the spider, she wears full pyjamas with a cover over – even when she requested to do it in a negligee, ”It was really conservative.”

After making a number of lousy westerns at Universal, Corday became fed up with bad genre roles. She turned down the role of the wife in The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review) and refused to make The Deadly Mantis (1957, review), a dangerous move as a contract player. She didn’t turn down the role because she disliked sci-fi films as such, but because she thought the roles were bad. She tells Weaver that she regrets not doing The Incredible Shrinking Man, since it became a classic, but on the other hand, she says, it did nothing for the woman who played ”her” role. While she only starred in three science fiction movies, Tarantula, The Giant Claw (1957, review) and The Black Scorpion (1957), Corday is held in high regard by fans as one of the best scream queens of 50s, partly thanks to her sex appeal, no doubt, but also because she was an actress who helf her own against the boys, and was actually a good, if somewhat limited, actress. Nevertheless, she had a hard time finding roles in the late 50’s, and after struggling along as a TV guest stars for a couple of years, she retired from acting in 1961, although she did a few small roles later in life.

Warner seems to have sought advice from the producers of another SF movie filmed in Mexico, The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956, review), as it reuses at least three actors who appeared in that film: Carlos Rivas, Mario Navarro and Pascual García Peña.

Once again, Rivas is cast as the Mexican side-kick. Rivas was born to a German father and Mexican mother in El Paso, and spoke English as his first language, which is probably why he made a rather effortless transition to Hollywood in 1956 after having appeared in a number of Mexican and Argentine films. He made a splash in 1956 with a co-starring role as Chinese lover Lun Tha in The King and I, opposite Rita Moreno and leading couple Yul Brynner and Deborah Kerr. Over the years he appeared in supporting roles in a handful of well-remembered movies, such as True Grit (1969) and Topaz (1969). However, after his first splash with The King and I, he was mostly confined to B-movies and TV guest spots. Rivas had a long career, still appearing actively into the 90s and even in a few roles in the 2000’s before his death in 2003. He SF roles include co-starring in The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956) and The Black Scorpion (1957). He also had a co-lead in 1963’s legendarily bad film The Madmen of Mandoras, re-edited in 1968 as They Saved Hitler’s Brain. He also appeared in the SF-ish Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze (1975).

Rotund Pascual García Peña was a beloved character actor of both comedic and serious roles in Mexican cinema. He also had roles in The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956) The Black Scorpion (1957), and turned up in El regreso del monstruo (1959) and Wrestling Women versus the Murderous Robot (1969). He also co-wrote a dozen scripts for directors like Chano Urueta and Rene Cardona.

The Black Scorpion features of Mexico’s most beloved character actresses, Fanny Schiller, who won two Ariel awards for best supporting actress and was nominated for two more. Here she is seen only briefly as a housekeeper. Schiller came from a family of performers and worked in comedy, as a dancer and in vaudeville, before becoming a star of the movies, the stage, and later television. During her movie career that stretched from the 20s to the 70, she appeared in over 200 films. While she appeared in many popular films in the 40s and 50s, few are known outside of Mexico today. Better known are the Disney films such as Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Lady and the Tramp and Sleeping Beauty, as well as the Hanna-Barbera TV show The Flintstones, which she all dubbed into Spanish. Schiller was also a social activist, who co-founded the Mexican actors union and was instrumental in establishing “nurseries” for actors’ children, where they would be taken care of and given a proper education.

Roberto Contreras seems to have followed the film crew back to the United States, where he became a prolific bit-part actor, and appeared in several high-profile movies and TV shows in small parts.

Willis O’Brien was one of the pioneers of stop-motion animation with puppets, and still regarded by some as the very best in his craft. O’Brien’s most famous work is the creation and animation of King Kong (1933) and Mighty Joe Young (1949), for which he won an Academy Award for best special effects. Sadly, for many of his later films he didn’t receive the resources or time to make the best of the material, and in some cases studios simply gave him a check to be able to use his name in the credits. Such was the fate of the infamous remake of The Lost World (1960), where he is credited as ”technical consultant”, although there is no animation in the film, rather the studio just used live lizards with crests and horns glued to them to make them look like dinosaurs. They didn’t.

The 1925 film The Lost World is sometimes called a ”dry run” for King Kong, but in fact O’Brien had been creating stop-motion dinosaurs for years, starting with his first animation film The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy. He made nearly an hour-long film about time travel back to the age of the dinosaurs in 1918 with The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (review). Unfortunately he received no credit for the film when it was released as an 11 minute short after his colleague, producer and co-animator Herbert M. Dawley cut down the film and removed his credits after a row between the two (O’Brien had previously released a press junket where he in turn had removed Dawley’s name). Dawley filed a patent for the stop-motion animation and tried to sue O’Brien for patent breach when The Lost World was released. Dawley has long been villified for this, but more recent examination of the circumstances seem to indicate that it O’Brien did indeed systematically downplay Dawley’s role in the development of his craft. It seems that it had in fact been Dawley that created the animated puppets used in The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, and that O’Brien showed them to puppet-maker Marcel Delgado, who more or less copied the principle of them for The Lost World. It was when Dawley saw early test footage of Delgado’s and O’Brien’s work for The Lost World, with puppets almost identical to the ones that he had patented, that he filed for a lawsuit.

Another animator that has frequently stood in the shadows of O’Brien was Pete Peterson. He was born in Denmark in 1903 as Svend Aage Pedersen and was working as a grip in Hollywood in the 40s. In 1949 he was called upon to light the miniature sets that O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen were animating for Mighty Joe Young, and was so intrigued by their work that he took up stop motion animation as a hobby. Toward the end of the filming, the animation was falling behind schedule, and he offered his services to help, and ended up animating a couple of major sequences. The film wound up winning an Academy Award for special effects.

Peterson returned to his work as a grip, but continued to dabble in animation in his spare time. In 1957 O’Brien called upon his services again when it came time to create the effects for The Black Scorpion. By this time, Peterson was suffering from multiple sclerosis, which was taking a toll on his ability to work as a grip, so he happily accepted the offer, and ended up as the main animator on the film. O’Brien and Peterson again combined their skill on the low-budget film Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review).

In the late 1960’s, after Peterson’s death in 1962, a group of young animators, including such later luminaries as Jim Danforth and Denis Muren, discovered a trunk containing Peterson’s test footage and models. Included here were footage for two short movies called Las Vegas Monster and Beetlemen. The armature of the Las Vegas Monster and one of the Beetlemen models were used in the SF softcore movie Flesh Gordon (1974). Peterson is credited on IMDb as one of the head re-creators in the SF comedy The Thing With Two Heads from 1972, but at that time he had been dead for 10 years.

Janne Wass

The Black Scorpion. 1957, USA. Directed by Edward Ludwig. Written by David Duncan, Robert Blees & Paul Yawitz. Starring: Richard Denning, Mara Corday, Carlos Rivas, Mario Navarro, Carlos Musquiz, Pascual García Peña, Fanny Schiller, Pedro Galvan, Arturo Martinez. Music: Paul Sawtell. Cinematography: Lionel Lindon. Editing: Richard L. Van Enger, Art direction: Edward Fitzgerald. Sound: Rafael Ruiz Esparza. Special effects: Willis O’Brien, Pete Peterson, Wah Cheng, Ralph Hammeras. Produced by Jack Dietz & Frank Melford for Amex Productions, Frank Melford-Jack Dietz Productions & Warner Bros.

Leave a comment