A married scientist shrinks his assistant and lover into a pocket-size statue. This French 1957 screwball sex comedy is a breezy piece of entertainment that suffers from a thin script and lazy special effects. 5/10

Amour de poche. 1957, France. Directed by Pierre Kast. Written by France Roche. Based on short story by Waldemar Kaempffert. Starring: Jean Marais, Agnes Laurent, Geneviève Page, Jean-Claude Brialy. Produced by Goldschmidt, Poiré & Thévenet. IMDb: 5.7/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Prof. Jerome (Jean Marais) is working on a formula for suspended animation. Through a misunderstanding, his cute student Monette (Agnès Laurent) believes that Jerome has hired her as his assistant, and one day she shows up at his lab. It doesn’t take long for Jerome to come to admire Monette’s go-getter attitude, and that she is both pretty and in love with him doesn’t hurt. Jerome has been trying his suspended animation serum on ants, but without result. Instead of suspending their animation, the ants simply vanish.

There is no love lost between Jerome and his wife Edith (Geneviève Page), who “loves the idea of marriage” more than she loves him, and has convinced him, against his will, to take up a lucrative contract with a soft drink company in the US — as his experiments with suspended animation don’t seem to bring him the fortune she had hoped for. However, things change when Monette is packing up his lab and accidentally spills a bottle of the serum on the floor, and his dog laps it up. Immediately, the dog turns into a white miniature statue of itself — it’s the suspended animation reaction that Jerome has been looking for. The ants didn’t disappear, they only turned to small to see. Jerome and Monette celebrate by sleeping with each other.

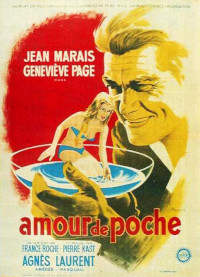

Amour de poche from 1957 is a French science fiction romcom directed by Pierre Kast, one of the lesser known directors and writers of the New Wave. It features one of the biggest stars of the French screen, Jean Marais and is based on American science writer Waldemar Kaempffert’s short story The Diminishing Draft. It was released in the US either in 1960 or 1962 (sources vary) as Nude in His Pocket, and later on TV with the less lurid title Girl in His Pocket, and on DVD as A Girl in His Pocket. The original title literally translates as “pocket love”. It is sometimes wrongly attributed as “Un amour de poche”

The problem with Jerome’s serum is that it is useless unless he can bring his test subjects back to life, which he can’t. Until one day, when he is cleaning out his lab and Monette bursts into tears, and accidentally touches the petrified ants, which spring back to normal size and life when they come into contact with her salty tears. Jerome rejoices and the two spend a day shrinking different animals and turning them back to life.

The title of the film stems from the next complications: One night Edith, who has been suspecting something is going on between Jerome and Monette, catches them in the act, when she knocks on the door to the lab. Edith thinks fast and takes a swig from the serum bottle, and is reduced to size of an Action Man doll. Jerome cleans away her clothes and puts her in his pocket. He and Monette have worked out that in order to bring the petrified specimens back to life, they need to be dunked in a sufficiantly large quantity of salt water, and Jerome struggles to find a container large enough for Monette, and finally decides to take her to the beach, and in the salty waters of the sea, brings her back to normal.

Monette soon devices a little game, in which she leaves a note for Jerome in which she states a place where she is going to drink the serum, and has Jerome come look for her, sort of playing hide and seek. But at one time, Edith finds the note and picks up Monette. When Monette (who has a sort-of-but-not-really boyfriend) goes missing, Jerome is accused of killing her. Edith blackmails him by giving the police an alibi for him, and in return has him promise to come to USA and work for her father’s soft drink company, so that she can have the good life that she has always dreamt of. Unaware of the effect that salt water has on the petrified specimens, she tells Jerome that as the ship to America departs, she will toss the statue of Monette into the sea, to, what she believes, her death. As the day of the departure approaches, Jerome reveals that he will not be joining Edith on the trip, but instead follows the ship in a small boat. When Edith finally drops Monette (there’s a last minute complication), Monette is brought back to life, and Jerome jumps into the sea to join her. The End.

Background & Analysis

Amour de poche, or Nude in His Pocket, came about in the late 50s at the cusp of the New Wave movement, a movement centered around the cinema journal Cahiers du Cinema. While director Pierre Kast was known as one of the members of this movement, Amour de poche is not a film that is recognisably made in the novelle vague style, but rather borrows its format from the Hollywood screwball comedy. This was Kast’s feature film debut.

The film is based on American science writer Waldemar Kaempffert’s short story The Diminishing Draft, first published in All-Story Weekly in 1918. Kaempffert was not a particularly prolific fiction writer, in fact this is the only fictional work of his listed by the Internet Speculative Fiction Database. It has been republished several times, and it is possible that Pierre Kast, an avid SF reader, might have come over it in Groff Conklin’s anthology The Big Book of Science Fiction, published 1950. However, the screenplay was written by France Roche, one of France’s leading film journalists, critic, screenwriter and occasional actress – well versed in romantic comedies.

The Dimishing Draft, while one can find some dry humour in it, is not a comedic text, but rather a sort of science fiction melodrama. The film follows the story very closely, however, it also pads out the running time by adding several new characters; Monette’s suitor (Jean-Claude Brialy), her best friend (Regine Lovi, I think), Edith’s best friend (France Roche) and a nutty professor, all of whom take up a good deal of screen time, with no consequence on the plot. They are there for allowing the main characters to give exposition and verbalize what is written in the story as inner monologues, and for providing some of the comedy and and pad out the running time. Screenwriter France Roche would have done well to add another subplot or another central plot element to the central story, as the film feels rather stretched out as it is, despite its modest 80-minute length. The main difference between the story and the film is the ending. The story ends in tragedy, with Edith throwing the statue of Monette onto the street, where it shatters. Of course, a romcom couldn’t end on such a bleak note, but the change also deprives the story of its poignancy.

The film has the distinct tone of a Hollywood screwball comedy, and it’s easy to see Gary Grant and Marilyn Monroe in the lead roles, like in Monkey Business (1952, review). It is quite possible that Pierre Kast was also inspired by Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review), which was released 4 months prior to Nude in His Pocket. The film hinges on the lurid idea of a man walking around with a nude miniature woman in his pocket. It is the ultimate male sex fantasy to have a willing nymph on you at all times, ready to activate at your will, or to simply stow away in your pocket when she is not needed. The absolute willingness of Monette to make herself a toy in Jerome’s hands, literally suspending the rest of her life while waiting for her lover, is a plot line that doesn’t win many feminist sympathies today. Both the story and the film paint two extremes of womanhood; the sparkly, submissive “dumb blonde” Monette and the gold-digging, controlling and scheming hag Edith.

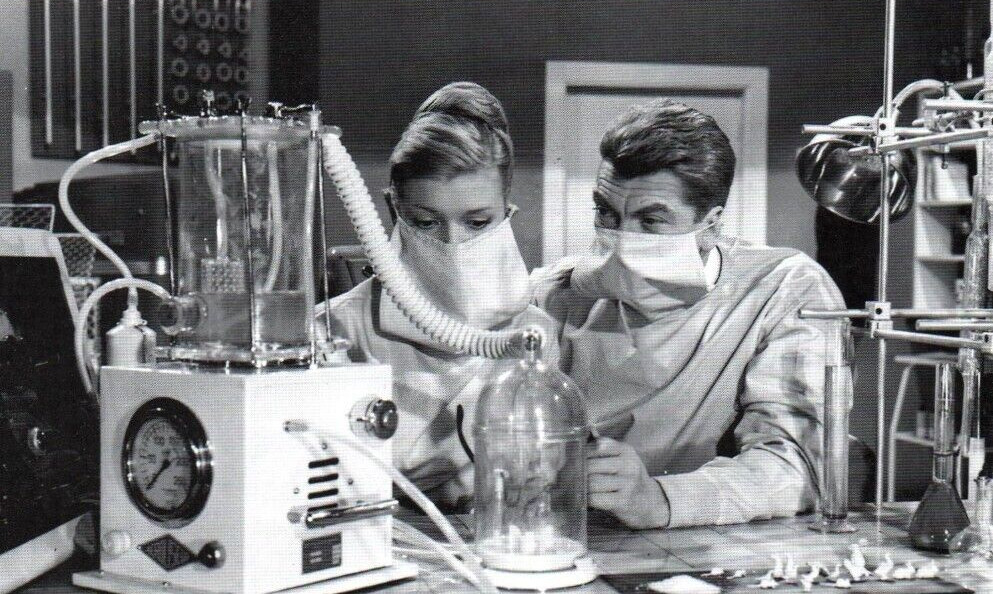

Viewers hoping to see a nude miniature Agnes Laurent will be sadly disappointed, though. One could argue that the special effects of the film are extremely crude, but that would imply that there are special effects in the film, which there aren’t. The miniature animals and miniature Monette are simply plaster cast models. The transformations are done through the rabbit-in-the-hat principle. Monette and Jerome put a plaster rabbit into an opaque container, the pull out a real rabbit. The transformations always occur off-screen or through lazy stop-start editing. One would have hoped for a little more innovation in a film that deals with size change as its central gimmick. Kast’s countryman Georges Méliès did better with the crude cinematic technology of 60 years past. Here one gets the feeling that Kast hasn’t even bothered to make an effort.

Even within the confines of the screwball SF comedy, the story strains credulity. Monette twitters away, happily playing hide and seek with Jerome in very public and extremely dangerous hiding places; the university park, a public beach, and a museum. Edith has already demonstrated how brittle the petrified animals are, by breaking a miniature rabbit on the floor. Even within the premise of the film’s nutty idea, it strikes a veiwer as extremely unlikely that Monette would risk being stolen by a child while petrified, stepped on or snatched by a bird or other animal. And the whole game they play is dependent on Jerome finding her – what if he doesn’t? When Jerome is accused of murdering Monette after Edith has snatched her up, it isn’t very far from the truth.

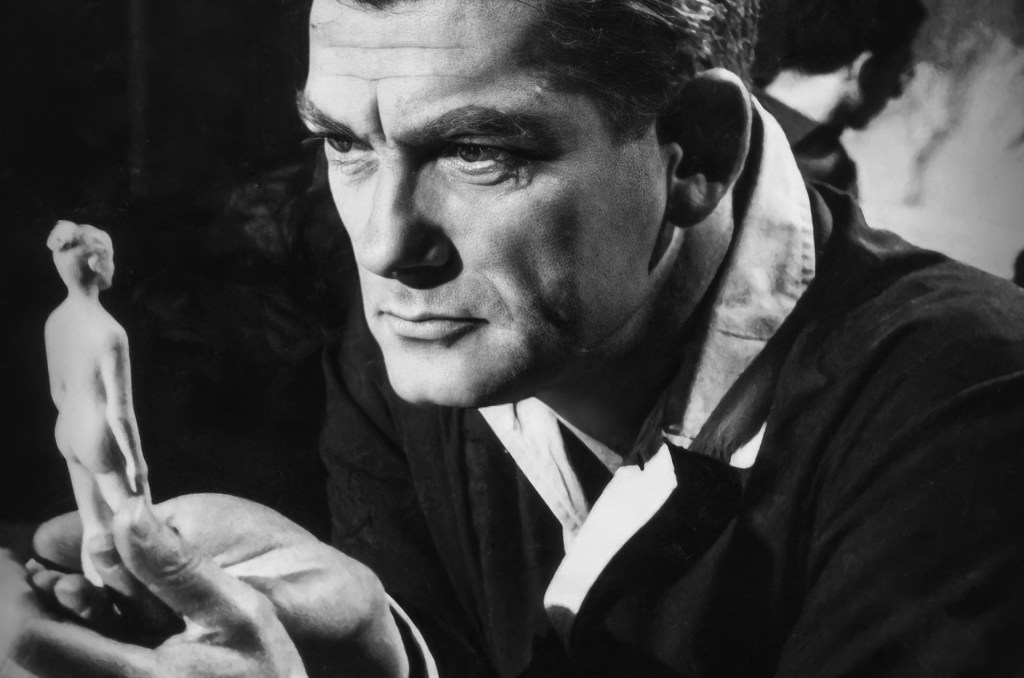

Pierre Kast, a former socialist organiser and freedom fighter against the Nazi-backed Vichy regime in France, would go on to make films which often ridiculed the life of the bourgeoise and Capitalist society. While the portrayal of Jerome’s gold-digger wife shows some of these traits, it would be a stretch to call Nude in His Pocket a satire. Rather, this is a light-hearted screwball sex comedy with a distinctly 50s Hollywood flavour. The film is carried by its main cast. Handsome Jean Marais gives a solid performance as the middle-aged heartthrob professor, which comes off as a bit of a mix between Cary Crant and Claude Rains. Agnes Laurent is the embodiment of the 50s French pixie girl, with a combination of childlike naiveté and sexual allure. While Genevieve Page is second-billed under Marais, her Edith really is more of a bystander in the movie, even if she is a central actor in the plot – she is competent in her role, as are most of the supporting cast.

While this was Kast’s feature film debut – he primarly worked as a writer for Cahiers du cinema – he had half a dozen short films under his belt, and had worked as an assistant director. Apart from the notable absence of special effects, Kast’s direction is fairly smooth and competent, and the film is well lit and crisply photographed by Ghislain Cloquet. The cast is largely made up of Kast’s friends, notably award-winning director Alexandre Astruc and screenwriter Jean-Pierre Melville. Amour de poche provided Jean-Claude Brialy with his first featured role – ge would go on to become an award-winning actor and director. Movie star Jean Marais was brought on board by screenwriter France Roche. Marais apparently didn’t get along with Kast and disliked his directorial choices. So upset was he with the end result that he threatened to pull out of the promotion of the movie.

Amour de poche is a competently made, light-hearted science fiction romcom, but, as film critic Bill Warren points out, while the pace remains brisk, the plot grinds to a halt towards the end and becomes repetitive. Nevertheless, a fun and entertaining French version of a screwball comedy that’s well worth checking out if you stumble over it (which you probably won’t). It is available on DVD with English dubbing under the title A Girl in His Pocket.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its US release in 1962, Gene Moskowitz wrote in Variety about Nude in His Pocket that it featured “meandering direction, telegraphed proceedings, sans the needed snap, lilt and sympathetic characterization”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Phil Hardy writes that Kast was “more at home filming conversation and witty lines […], rather than making movies”. Hardy cites Amour de poche as Kast’s best feature film, “for its light-hearted, tongue-in-cheek approach to Science Fiction”. French film historian Jean Tulard, on the other hand, wrote in his book Guide des filmes that “Pierre Kast was a good connoisseur of science fiction literature, a good author himself, but unfortunately not a good director in this field”. In Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren writes that the film is “bright and funny with good performances and production values. […] The most serious defect is the plot deflating once the petrifying formula is perfected and Jerome and Monette are in love.”

Amour de poche is a very obscure film, and only has around 70 audience ratings on IMDb, with an average of 5.7/10 stars. Dave Sindelar writes a positive review on Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings: “The gimmick that drives it is fairly amusing, and in general I quite enjoyed it, though it does get a little too obvious on occasion. […] All in all, it’s fairly innocuous, but it does have its charms”. Steve Morrisey at MovieSteve gives the film 3/5 stars, writing: “Pierre Kast directs in a clean, snag-free style and like all farce it’s a portrait of people at their worst, though presented in a light-hearted and palatable way”.

Cast & Crew

Pierre Kast, born in Paris in 1920, has an interesting life story. A socialist activist and organiser from a young age, he was one of the leaders of the socialist youth movement during the Nazi occupation of France. Kast was a central organiser of protests and active in the armed French resistance movement against the Nazi-backed Vichy regime. In 1940 he was arrested and served five months in prison, only to continue his resistance activity when he got out, and was able to evade the authorities for the next four years.

With the war at an end in 1945, Kast dedicated himself to his lifelong passion of film, starting as an employee at the French film archive Cinémathèque française and started writing film critique. With the foundation of the legendary film journal Cahiers du cinema in 1951, he quickly became one of its most prominent writers and a central part of the novelle vague movement. In 1949 he struck up a fruitful companionship with director Jean Gremillion as both screenwriter and assistant director, and began directing his own short films. He worked as an assistant director not only for Gremillion, but also René Clément, Jean Renoir and Preston Sturges.

The SF comedy Amour de poche/Nude in His Pocket (1957) was his feature debut as a director, and would go on to direct around a dozen dramatic features, as well as a few documentaries and TV movies. He worked as screenwriter on over 20 films. While his films were moderately popular in France, few are widely known outside of the country. Today Kast is probably best remembered for his two science fiction movies, Nude in His Pocket and the “ancient aliens” film The Suns of Easter Island (1972). He published one novel, The Vampires of Alfama, which is a parallel history novel set amongst vampires in Lisboa in the 18th century. He was seen as one of France’s most prominent critics and experts on science fiction films.

On English-language websites, France Roche, who wrote the screenplay for Amour de poche, is usually presented as a screenwriter and actress. However, in France she is known as one of the country’s foremost film journalists, critics and TV hosts. In the 50’s, Roche was given charge of the cinema pages in one of France’s largest newspapers at the time, France-Soir, making her one of the country’s most influential critics. In 1959 she embarked on her decades-long career as a culture and film journalist and host on France’s public service TV network, where she appeared on or hosted several popular TV shows on film, fashion and entertainment. She is perhaps best remembered for her interviews with movie stars like Brigitte Bardot, Kirk Douglas, Jean Marais, Jeanne Moreau and Woody Allen. From 1969 Roche was employed as the head of the culture department at the channel Antenne 2 (current France 2). In 1961 she was part of the jury at the Cannes Film Festival.

After Roche’s death in 2013, France’s minister of culture, Aurélie Filippetti, presented her official condoleances, saying “France Roche, through her professionalism and her great elegance, was the spitting image of the movie stars who confided in her. France Roche has left her footprint on French cinema.” Her career as a scenarist and actress is mentioned merely as a footnote in French obits.

Jean Marais was one of the biggest stars of French cinema in the 50s and 60s. He began appearing in films in the early 30s, mainly in small parts supplementing his work on stage. He was “discovered” by multi-artist Jean Cocteau in 1937, who proceeded to cast him in leads in several of his plays. Marais, openly homosexual, was also Cocteau’s lover between 1937 and 1947, and they remained lifelong friends and collaborators. According to film historian Bill Warren, “although he was very good-looking, his acting abilites were limited”. Nevertheless, he ascended to movie stardom when Cocteau cast him in the lead of The Beauty and the Beast in 1946, which remains his best-known movie. Marais appeared in several of Cocteau’s films in the late 40s, and played leads in several commercial successes for other directors in the 50s, not seldom historical dramas, melodramas and adventure films, including the hugely successful The Count of Monte Cristo (1954).

An even bigger hit was the swashbuckler movie Le Bossu (1959), which launched a new chapter in Marais’ career. In short succession, he starred in several popular swashbucklers, including the Italy-based production Romulus and the Sabines (1962) oppisite Roger Moore. Speaking of Moore, the James Bond fever also reached France after Dr. No (1962), and Marais went on to play Bond-inspired spies in several movies, including The Reluctant Spy (1963). He got his biggest hit since Le Bossu with the spoof remake of the classic silent crime serial Fantomas in 1964, which spawned three sequels, and in 1966 he played the role that originally made Roger Moore famous in The Saint Lies in Wait. In the 70s Marais decided to focus more on his stage work, but he continued to appear in films sporadically during the following decades. His last movie appearance was a supporting role in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty in 1996. He passed away two years later. While his acting didn’t receive any accolades in form of awards, or even award nominations, in France (apart from a lifetime achievement César in 1993), Marais was hugely popular in Germany, where he was nominated for the Best International Actor Bambi award a whopping seven times – and won it three times.

Agnès Laurent had a short but fairly successful movie career as a Brigitte Bardot lookalike between 1956 and 1961, often playing roles that required little wardrobe. In France she is best remembered for the exploitation sex comedy The Nude Set (1957), originally Mademoiselle Strip-tease. She did a few films in Germany, Italy and Spain, and is possibly best remembered outside of France for appearing in the title role of the British production A French Mistress (1960), described on IMDb as “a breezy comedy with plenty of ooh la la!”

Geneviève Page had a significantly longer and more prestigious career spanning five decades. She started her career on stage, and would remain active in theatre during most of her film career, at one point being awared with the prestigious Molière award. Page made her film debut in 1951, and in 1954 had her first starring role. She soon began appearing in foreign films and starred opposite Robert Mitchum in Foreign Intrigue (1956). She had supporting roles in Anthony Mann’s El Cid (1961), John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (1966) and Terence Young’s Mayerling (1968). Her biggest success came supporting Catherine Deneuve in Luis Buñuel’s classic Belle de Jour in 1967, which garnered her a Best Supporting Actress nomination by the US National Society of Film Critics. However, the role she is probably best remembered for is the seductive villain in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970). She made her last film appearance in 2003.

As the movie is made by a cineaste with the help of his cineaste friends, there are too many prominent filmmakers making cameos for us to single them out here. None of them have done much SF outside Nude in His Pocket.

The music for the movie is provided by three different composers, including Georges Delerue, who would go on to provide the score for such Hollywood films as The Day of the Jackal (1973), Platoon (1986) and Twins (1988), won an Academy Award and three César Awards. There’s also some jazzy tunes by Alain Goraguer, best known as composer/arranger for Serge Gainsbourg. Marc Lanjean is perhaps best known for putting down in writing the French lyrics of the West Indian folk song “Maladie d’amour”, which can also be heard in numerous films, inlcuding Ocean’s Eleven (2001).

Janne Wass

Amour de poche. 1957, France. Directed by Pierre Kast. Written by France Roche. Based on short story “The Diminishing Draft” by Waldemar Kaempffert. Starring: Jean Marais, Agnes Laurent, Geneviève Page, Jean-Claude Brialy, Jean-Paul Moulinot, Amédée, Régine Lovi, Fred Pasquali, Hubert Deschampes, Jaqcues Hilling, Jöelle Janin, Alexandre Astruc, Christian-Jaque, Jean-Pierre Melville, Boris Vian. Music: Georges Delerue, Alain Goraguer, Marc Lanjean. Cinematography: Ghislain Cloquet. Editing: Monique Isnardon, Robert Isnardon. Art direction: Sydnet Bettex, Daniel Villerois. Costume design: Virginie. Sound: Jean Bertrand. Produced by Goldschmidt, Poiré & Thévenet for Madeleine Films, SNEG & Contact Organisation.

Leave a comment