Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers and Marilyn Monroe shine in this nutty 1952 screwball comedy where a nutty professor’s chimp invents a rejuvenation serum, with hilarious results. Howard Hawks’ direction overcomes the thin script. 7/10

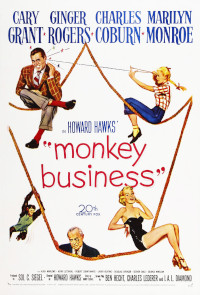

Monkey Business. 1952, USA. Directed by Howard Haws. Written by Ben Hecht & et.al. from story by Harry Segall. Starring: Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Marilyn Monroe, Charles Coburn, Hugh Marlowe.Produces by Sol C. Siegel. IMDb: 7.0/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 88/100. Metacritic: N/A.

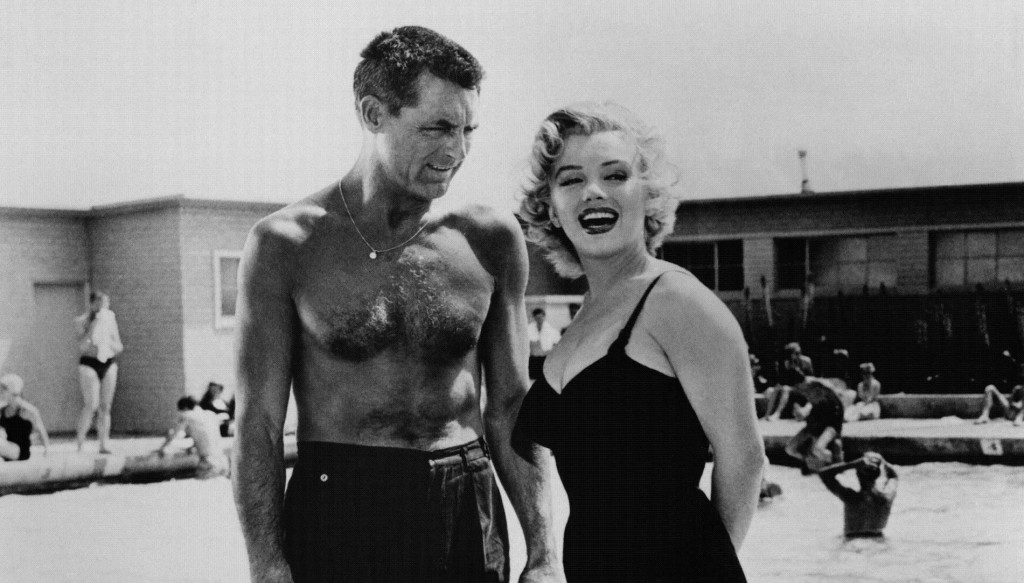

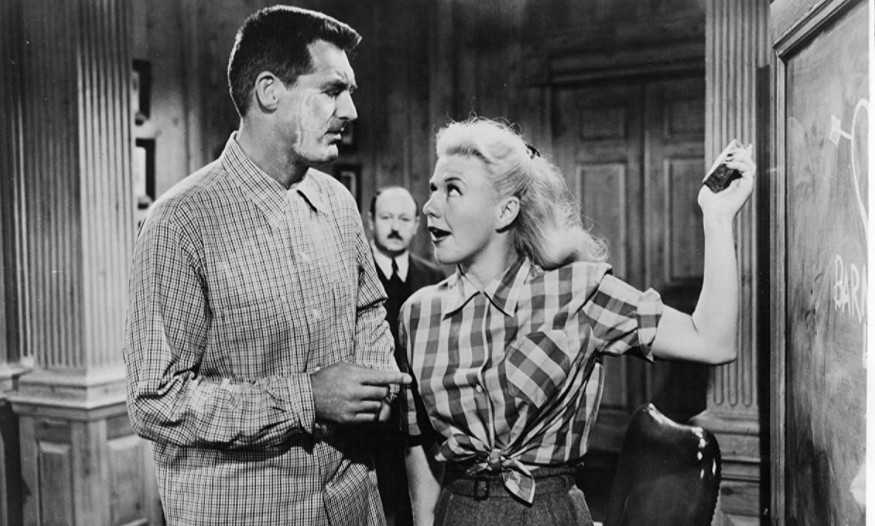

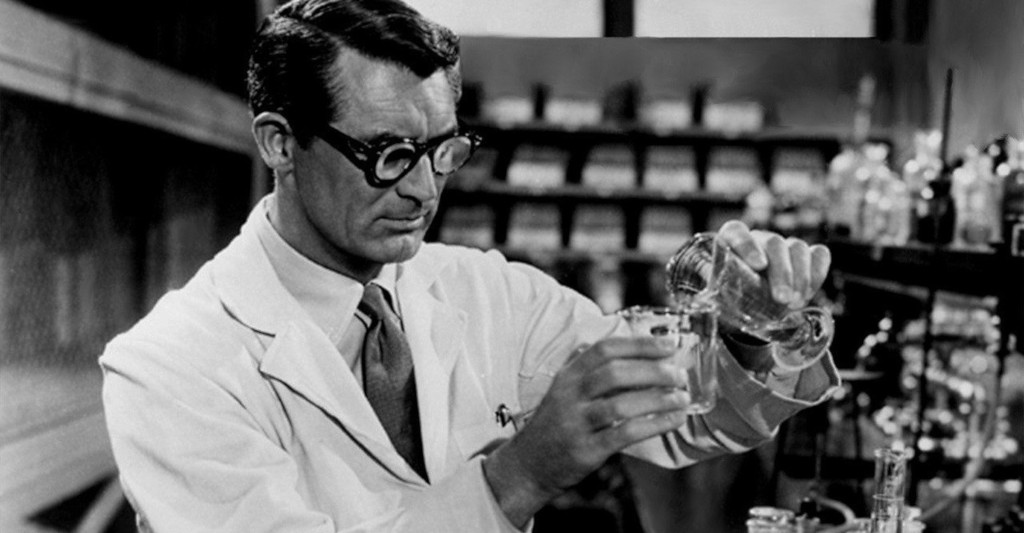

Dr. Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) is a middle-aged industrial scientist working on a youth formula, getting so caught up in his work that he sometimes neglects his loving, but sometimes annoyed wife Edwina (Ginger Rogers). Frustrated over his repeated failures to producer said formula, he forgets to lock the cage of one of his test monkeys, the chimp Esther. While Barnaby and his assistants are away, Esther mixes up the correct formula for the youth potion and pours it into the water cooler. When Barnaby gets back, he decides to test his latest brew on himself, and chases it down with a glass of water from the water cooler. A few minutes later the absent-minded professor starts acting like a college kid, buys a sports car and spends the day roller-skating, swimming, speed-driving and flirting with his boss’ dumb bombshell secretary (Marilyn Monroe). After eight hours the the formula wears off, and Barnaby calls down his boss Mr. Oxley (Charles Coburn) to his lab tell him the news and try another dose. But before he has the time to take another shot of the serum, his wife Edwina drinks it, and like Barnaby, chases it down with water from the water cooler. Edwina regresses even further, and starts acting like a wild an emotional teenager, with potentially dire consequences and loads of hilarious results. The last part of the movie have the Fultons regress even to childhood, and that’s when the board of executives at Barnaby’s firm demand he hand over the formula to them — at any price he wishes to ask. “A zillion dollars!” says Barnaby, who’s more interested in tickling Esther under the boardroom table. Of course, in the end, the entire board goes bananas on the water from the water cooler.

A while back I reviewed an obscure Finnish SF comedy from 1948 called Hormoonit valloillaan (“Hormones on the loose”), which was based on the 1946 novel Hormoonit hallitsee (“Hormones rule”) by Armas J. Pulla. What strikes me is that Monkey Business, made four years later, is an almost carbon copy of the Finnish picture. At their core, both films deal with the notion of a mature couple, who have seemingly lost the spark in their relationship and are going by their humdrum lives without much taste for adventure or sex. Both portray a male lead stuck in a middle-managerial position at their company, and both include a stuck-up meddling colleague/friend who tries to use the male lead’s regression as a way to discredit him. In the case of Monkey Business, this is Edwina’s childhood sweetheart Hank (Hugh Marlowe), who is now Edwina’s attorney, and whom Edwina calls in her childish bouts, accusing Barnaby of being mean and “hitting her” (which he doesn’t). In the Finnish film it’s the female leads who secretly dates the hunky co-worker, and in the US movie it’s Grant who takes out Marilyn Monroe for a ride, while Rogers confides in Marlowe. And in both movies the stuck-up hunk is tied to a pole by the male lead who’s enlisted a gang of kids playing Indians to help him with his revenge plot. And both Hormoonit valloillaan and Monkey Business end on the notion that you are only as old as you feel inside, with the main couple having rekindled their sexual desire for each other, remembering why they fell in love in the first place.

Monkey Business was based on a story by playwright and screenwriter Harry Segall, and I’m pretty sure neither he nor director Howard Hawks had been seen Hormoonit valloillaan nor read the novel it was based on. But the similarities can’t be entirely coincidental, and I would suggest that there is some other, earlier, work that both movies draw their inspiration from. However, I am at loss as to what this could be. There is a silent film, also rather obscure, from 1920 called Monkey Shines, which seems to have a somewhat similar setup. The problem is that I haven’t been able to find the film online, nor a reasonably priced DVD, so I can’t say how much of these stories might be derived from it. On the other hand, this is such a classic trope that I’m sure there are numerous novels and short stories out there that share similar themes and situations.

Monkey Business has three things going for it: a star cast, a star director, and the appropriate budget to go with that combination. Not that this film couldn’t have been done on a meagre budget: there are few special effects, apart from some wonderful stunt driving, no expensive set pieces. But of course, money guarantees talent, time and and solid craftsmanship, and in particular the last two have often been sorely missing from many of the films I review on this blog. While Monkey Business has its flaws, mainly in the scripting department, it is nice to be able to sit down and watch a film that is simply solid in all departments from start to finish.

Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Marilyn Monroe and Charles Coburn are some of the greatest comedic actors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Especially the old-timers shine in Monkey Business. Grant wasn’t the most versatile of actors, but few had as impeccable comedy talents as he. Here, his transformation from docile, work-absorbed professor to mischievous kid is magnificent. When in boy-mode, the 48-year-old actor jumps on furniture, runs around like a schoolboy and does his signature cart wheel from yesteryear movies. But Rogers is equally superb, doing a perky Marilyn Monroe routine in front of the 15 years younger Monroe. Monroe gets few chances to shine in this film, as she is constantly the butt of jokes on the dumb secretary’s behalf, and in the picture provide Grant with some sexa appeal (not that Rogers, 41, has lost any of hers). But as always, Monroe does her schtick with integrity and finesse. And Charles Coburn rounds up this comedic powerhouse with another great performance and impeccable timing.

A recurring problem with SF comedies is that they beat their central gag to death. Such was the case, for example, with the 1949 baseball movie It Happens Every Spring (review). The central premise of a baseball-crazy college professor accidentally inventing a formula that makes a baseball bat repel a ball is not bad in and of itself, but doesn’t hold up as a central premise for a feature film on its own, and pretty soon the joke wears out it welcome. The same problem occurred in Hormoonit valloillaan: the movie introduces the youth serum in he beginning of the film, and the rest is basically a number of set pieces constructed around the gag of grown-ups behaving like naughty children. Monkey Business partly falls down the same hole. Hawks does structure his movie better by setting up different scenarios for each bout of rejuvenation: First it’s Grant looking for his lost sexual drive and joie de vivre. Then it’s Rogers, reliving both the romance and the anxiety of the couple’s wedding night. Then it’s the two of them together, and it is this part thar starts feeling a little bit too much like stretching the gag, as this last bit has little to do with Barnaby and Edwina exploring their relationship. The film picks up again toward the end, which is as happy as it is predictable.

Monkey Business was made before Jerry Lewis perfected the mad scientist comedy in what may be his masterpiece, The Nutty Professor, in 1963. But the trope was already old, almost as old as movies themselves. The nutty professor was a mainstay of French pioneer Georges Méliès, most often played by the actor/director himself. For Méliès, the loopy inventor was a conduit to showcase special effects and to swoop the audience along on his wonderful adventures in the very earliest days of cinema. But another trope quickly followed, that still serves as the template for the nutty professor subgenre — the comedy inversion of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has been called the most often adapted literary work in film history — with most adaptations being made before 1930. It was one of those stories that was turned into film sometimes several times a year. The first known comedy version was made by Selig Polyscope in 1909, and included a male-to-female transformation. One of the more famous Jekyll/Hyde spoofs was the 1925 Stan Laurel short Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pride, in which Laurel spoofed John Barrymore’s legendary 1920 portrayal of the dual role. In Universal’s SF horror films, doctors Frankenstein and Jekyll started to amalgamate with H.G. Wells’ Dr. Griffith (who of course was inspired by Stevenson’s character as well), and 1940’s The Invisible Woman (review) was the first all-out screwball comedy “based” on the Universal horror franchise. Ironically, John Barrymore was back as a nutty professor, even if he didn’t turn himself invisible in that film. A similar setup of a dotty old scientist, this time creating an artificial woman, can be seen in the British farce The Perfect Woman from 1949 (review). The same year saw the release of the above mentioned It Happens Every Spring, which is where we really first start to see the modern version of the nutty professor taking shape — in the sense that the scientist uses himself as guinea pig, so to speak. In 1950 Alec Guinness invented not a ball-repelling baseball bat, but an indestructible fabric, from which he tailors himself a suit, in the Ealing Comedy The Man in the White Suit (review), with dire consequences. And credit where credit’s due: It’s actually Hormoonit valloillaan that finally brings the nutty professor back to his Jekyll/Hyde roots by giving the protagonists a personality-altering drug.

There really hadn’t been many actual films like Monkey Business when the movie came out, if we look at it from its SF angle, but still contemporary critics called the central gag old hat, revealing that this was a well-used trope in1952, even though it was fairly novel to feature films at the time, in its purest form. Pseudonym Bron wrote at Varity: “Some important names, production as well as cast-wise, are involved here, for disappointing results. Attempt to draw out a thin, familiar slapstick idea isn’t carried off. […] Occasional scenes are briefly funny but are not sustained, and the joke wears thinner as it’s spun out into further developments.” Likewise, Bosley Crowther at the New York Times, while giving the acting and directing high praise, wrote: “The trouble, we’d say – if trouble is what you’d call an extended barrage of whooping childish behavior by a film-full of grown-up clowns – is that a screwball idea like this one can be kept funny just so long, which is maybe thirty-five or forty minutes, and then it blows up and that’s the end”.

Monkey Business fared OK at the box office, but wasn’t a thundering success. It’s reputation persists today, perhaps mainly on the star power of its lead actors. Almar Haflidason att BBC gives the picture 3/5 stars, writing that “the best moments [emerge from …] Cary Grant and Marilyn Monroe“. TV Guide likewise deals out a 3/5 rating, calling it “a slight film, improved greatly by the actors involved. Even with such a venerable creative team, it barely manages to evoke memories of some earlier comedies of the same ilk.” Craig Butler at AllMovie, in a 3.5/5 star review, acknowledges that he movie is “a very entertaining, if immensely silly piece of fluff”. Despite its zaniness, Butler writes, ” it’s still very much a Hawks film; the care he takes in setting up punchlines, the attention to precise timing, the seemingly carefree flow, the improbability that seems somehow grounded in a strange kind of reality prove this”. Still, Monkey Business has its defenders today, like Larushka Ivan-Zadeh at British Times, who gives it 4/5 stars, calling the picture “a gloriously silly treat”. Peter Bradshaw at the Guardian feels that the movie is “due for re-evaluation”. Bradshaw notes that it is “undervalued by some”, but that ” I can only say that this film whizzes joyfully along with touches of pure genius: at once sublimely innocent and entirely worldly”. Time Out is sold, calling Monkey Business an “immaculate screwball comedy by its greatest practitioners. […] The classic inverted-world comedy, where kids and animals bring sexual anarchy into the demure adult world, leaving all inhabitants much refreshed and highly amused.”

Of course, the script is silly, but it’s a screwball comedy, so that comes with the package. Hawks wisely builds up the energy and frenzy of the movie — the beginning seeming almost like slow-motion compared to what we are used to seeing from the director. However, the idea doesn’t quite hold up for a feature film, and during the second third it feels as if the picture is repeating itself to pad out the run-time. Still, any film that is as well directed and well acted as this one is always worth watching, and the actors raise this effort well above its flimsy script. The four lead actors are all such who command the screen when they are on it, and that they still manage to be at the centre of the viewer’s attention even while there is a remarkably well trained monkey on the screen is proof of why they were some of the biggest stars of their day. The films isn’t too loud or irritating, as is often the case with these kind of pictures, and there are no annoying comic relief characters. It is a dignified film that nonetheless doesn’t take itself one bit seriously.

I usually round up my reviews with a presentation of the cast and crew of the movie, but in this case it seems redundant as far as the main cast is concerned. It’s a travesty that Cary Grant never won any of the big three movie acting awards, although he was nominated for all three several time. He did, however, receive an honorary lifetime Oscar in 1970, after his retirement. Monkey Business was Grant’s only brush with SF. Ginger Rogers, on the other hand, did win an Oscar, in 1940, for Kitty Foyle. She was also nominated for a Golden Globe — for Monkey Business, no less. and the same year Grant picked up his honorary Oscar, she received a lifetime achievement award from at the Berlin Film Festival. Both Grant and Rogers are amongst the chosen few honored by the Kennedy Center. Like Grant, Rogers did no other SF, and neither did Monroe. Coburn did appear in a couple of more SF-ish comedies, The Rocket Man (1954) and The Story of Mankind (1957).

But there are some among the cast that have a pretty decent SF track record. Hugh Marlowe, playing Rogers’ ex, also played the meddling boyfriend in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review). Marlowe then went on to play the hero in two science fiction movies in 1956: World Without End (review) and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (review). He had a supporting role in Castle of Evil (1966). Marlowe was a radio and stage actor who usually played second leads or supporting characters in movies. He was able to get steady employment up until the end of the sixties, when he got a starring role in the TV series Another World (non-sci-fi, despite the name), a position he held until his death in 1982.

One of Cary Grant’s colleagues around the lab is played by a minor SF legend, Robert Cornthwaite, best known for his role as the cold-hearted Dr. Carrington in Howard Hawks’ The Thing From Another World (1951, review). Theatrical actor Cornthwaite became something of a fixture in sci-fi films, appearing in a number of classic movies, and some not so classic. He often played scientists of authority figures. He appeared in The War of the Worlds (1953, review), Reptilicus (1961), Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), Futureworld (1976), Time Trackers (1989), and reprised his role as Dr. Carrington in the spoof The Naked Monster in 2005 (he actually filmed his part in 1984, along with Kenneth Tobey, but that’s a story for another time). He also appeared in a large number of sci-fi series, including Men Into Space (1959), The Twilight Zone (1963), Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1965), Batman (1966), and The Pretender (1998). Apart from his stage career, he appeared on around 150 TV series in his career.

And if we’re looking for someone from the third SF classic from 1951, When Worlds Collide (review), then look no further than to another one of Grant’s colleagues, Larry Keating, who played Dr. Hendron, the scientist who invents the space rocket in the former movie. And there’s another one of the central characters from The Thing on board as well, Douglas Spencer, who played the reporter Scotty, who got the honour of ending said movie with the famous “Watch the skies!” line. In Monkey Business he plays yet another of Grant’s colleagues. Spencer also appeared as The Monitor in This Island Earth (1955, review). George Winslow, who plays the leader of the gang of kids that help Cary Grant scalp Hugh Marlowe later turned up as the central character in The Rocket Man opposite Coburn, SF stalwart John Agar and the legendary Anne Francis.

In the cast is also a young Kathleen Freeman, whose rectangular features and famous scowl has made her everyone’s favourite ragata, whether it be as Jerry Lewis’ nurse in The Ladies Man (1961) or the demonic Sister Mary Stigmata in Blues Brothers (1980). And talking about The Nutty Professor, Freeman actually appeared in Jerry Lewis 1962 movie as one of the major characters, and had a cameo in Eddie Murphy’s remake sequel, Nutty Professor II: The Klumps (2000). She was also very memorable as the housekeeper Emma in the original The Fly (1958) opposite Vincent Price, and appeared in The Magnetic Monster (1953, review), The Strongest Man in the World (1975), Heartbeeps (1981), Innerspace (1981) and Baby Geniuses (1999).

Also appearing in bit-parts are prolific character actors Harry Carey Jr. and Dabbs Greer, two gentlemen who will be recognisable to modern audiences by face, if not by name. Carey appeared in Cyborg 2087 (1966), UFOria (1984), Cyborg 2000 (1987) and Back to the Future Part III (1990). Greer can be seen in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), The Vampire (1957, review) and It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958). Charlotte Austin is best known for appearing as “the other woman” in Gorilla at Large (1954) and Frankenstein 1970 (1958). Some critics have made a thing out of Roger Moore appearing in a small role as a driver. But this is another Roger Moore, a prolific bit-part actor born in Chicago, best known for being named Roger Moore. In 1952 the future James Bond was still a struggling actor back in the UK, working as a model, in fact, a rather famous model for knitwear, earning him the nickname “the Big Knit”. It wasn’t until 1953 that he headed over to the US and started working as a TV actor, appearing in television adaptations of stage plays for NBC. Perhaps Hollywood was only big enough for one Roger Moore, because the American Roger Moore left the movie business in 1953.

Janne Wass

Monkey Business. 1952, USA. Directed by Howard Haws. Written by Ben Hecht, Charles Lederer, I.A.L. Diamond & Howard Hawks from a story by Harry Segall. Starring: Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Marilyn Monroe, Charles Coburn, Hugh Marlowe, Henri Letondal, Robert Cornthwaite, Larry Keating, Douglas Spencer, Esther Dale, George Winslow. Music: Leigh Harline. Cinematography: Milton Krasner. Editing: William Murphy. Art direction: George Patrick, Lyle Wheeler. Costumes: Travilla. Makeup: Ben Nye. Sound: W.D. Flick, Roger Heman, Sr. Visual effects: Ray Kellogg. Produces by Sol C. Siegel for 20th Century Fox.

Leave a comment