Meteor fragments that start growing into the size of skyscrapers and topple over threaten a small Southwest US town. Universal’s 1957 effort is one of the better late 50s B SF movies. 6/10

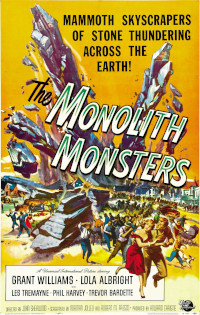

The Monolith Monsters. 1957, USA. Directed by John Sherwood. Written by Robert Fresco, Norman Jolley. Starring: Grant Williams, Lola Albright, Les Tremayne, Trevor Bardette. Produced by Howard Christie. IMDb: 6.3/10. Letterboxd: 3.0/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Strange black rock fragments suddenly turn up in the desert mountains outside a sleepy smalltown in the American Southwest. Geologist Ben Gilbert (Phil Harvey) takes a sample for investigation, but can’t identify it. When it accidentally comes into contact with water, it grows exponentially, not only wrecking his house, but also killing Ben by petrifying him. The same fate threatens little Ginny Simpson (Linda Sheley), who picks up a rock on a class trip and throws it in a bucket of water when she gets home.

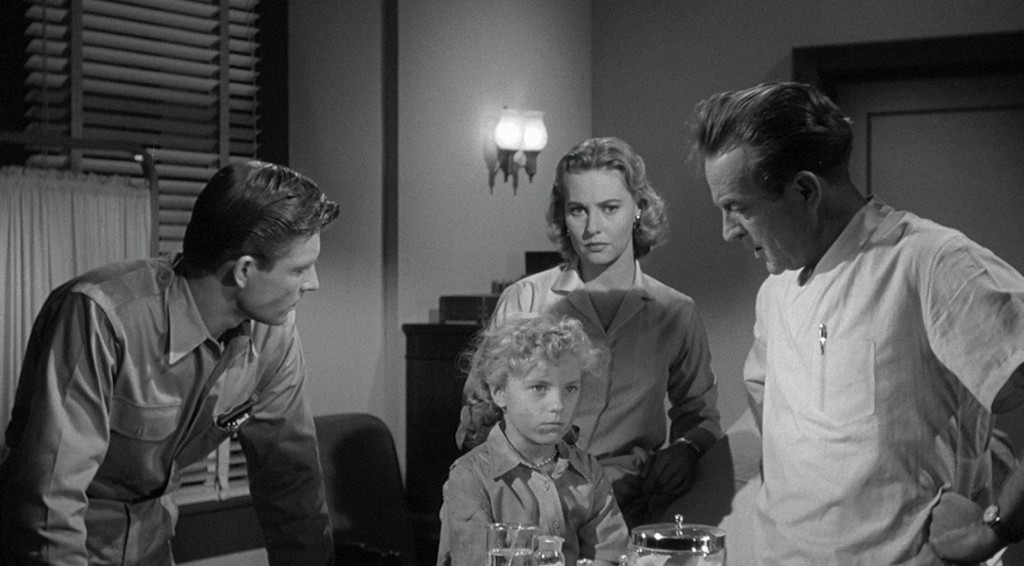

Ben’s colleague Dave Miller (Grant Williams) and his girlfriend Cathy Barrett (Lola Albright) find Ginny in a catatonic state in the ruins of her house, and when local doctor Reynolds (Richard Cutting) can’t help her, she is rushed to the big city where specialist doctor Hendricks (Harry Jackson) takes her into his care. When Dave can’t figure out what the rock is or why it suddenly starts growing and petrifying people, he calls on his old professor Flanders (Trevor Barnette), who figures the rock comes from a meteor. Flanders accompanies Dave to the small town, and together with Dr. Hendricks and local newspaper editor Martin (SF staple Les Tremayne), they begin a race against time: to find out what the rock is, why it grows, and how to reverse the process – before little Ginny dies – and, it will turn out – before the rocks in the meteorite crater start growing and crush the whole town beneath them.

This is the intro to one of Universal’s last SF “classics” of the 50s, The Monolith Monsters (1957). Universal assigned the film to screenwriter Robert Fresco and director Jack Arnold, who had been very successful two years earlier with Tarantula (1955, review). Arnold, however, pulled out, and the film was directed by John Sherwood. While made on a small budget, the film has a better-than-average reputation for a late 50s SF/monster movie.

Dave and Prof. Flanders hole up in the lab and do experiments on the rock samples, trying in vain to try to get it to grow. Nothing works, until Flanders accidentally chips a piece into the sink, and Dave pours water for the coffee – and suddenly a black miniature monolith grows out of the sink. At the same time, the rain starts pouring outside, causing the fragments littering the mountains to grow into enormous monoliths. When reaching skyscraper heights, the monoliths fall over and shatter, and from the shattered fragments new monoliths grow. Now the monoliths are advancing down the ravine towards the small town.

Meanwhile, the scientists have figured out that the monoliths get their mass from drawing the silica out of the soil, and probably do the same with human bodies. In the city, Dr. Hendricks has devised an antidote to the process, and little Ginny quickly recovers. Not a minute too soon, as half-petrified citizens of the small town soon start piling into Dr. Reynolds’ office, while police chief Corey (William Flaherty) and newspaper man Cochrane try to get word out to evacuate the town.

The rain eventually stops, and the weatherman (William Schallert in a fun cameo) forecasts two days of sunshine. That’s how long Dave and Flanders have to figure out how to stop the monolith monsters. Or actually, less than that, as the crystal menace continues to grow despite the rain stopping – it keeps drawing moisture from the ground. The two geologists test every combination they can think of in Dr. Hendricks’ serum, but nothing seems to be able to halt the growth in the rocks. Until Dave remembers that Hendricks mentioned that he diluted the serum with a saline solution. And lo and behold! Salt water seems to do the trick. Luckily for Dave, the small town operates a salt mine, which so happens to be next to the opening of the ravine in which the monoliths are advancing, and also just so happens to be next to a dam. The only way to stop the monsters, Dave figures, is to blow the dam and let the water flow over the salt mine, and into the ravine where it will stop the advance of the monstrous rocks. But for blowing the dam, they need permission from the governor – and he ain’t answering his phone …

Background & Analysis

“How do you make a movie about rocks that grow?” laments screenwriter Robert Fresco in an interview with film historian Tom Weaver. And sure enough, this film has all the ingredients of a dreadful turkey. However, Universal’s producers weren’t the first to get this idea – this was the second movie about growing rocks that threaten the world to come out in 1957. The first was Columbia’s ultra-cheapo The Night the World Exploded (review), in which rocks buried in the Earth’s crust come in contact with air due to excessive mining, and start growing and exploding. In that film, water is the solution and not the menace. The Night the World Exploded was hampered by a lack of a special effects budget and a drawn-out script which consisted mostly of padding, as the screenwriters didn’t quite know how to “do a movie about rocks that grow”. Robert Fresco also didn’t think he knew how to write a good movie about rocks that grow, but The Monolith Monsters stands head and shoulders over its Columbia counterpart – in part thanks to the excellent effects, but also because of Fresco’s smart writing.

The late 50s were a kind of schizophrenic time for SF movies. On one hand, major studio interest in science fiction had largely waned due to a percieved disinterest with audiences. On the other hand, never had so many SF movies been churned out of Hollywood than in 1957 and 1958 – almost exclusively low-budget exploitation movies aimed at the juvenile and teen market, with American International Pictures leading the way. Universal had been the leading studio in SF during the early 50s, with producer William Alland and director Jack Arnold making intelligent, atmospheric movies on a tight, but still substantial, budgets, films like It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review) and Tarantula. In 1955 Universal gambled with a big-budget SF epic in colour, This Island Earth (review). And although not an outright flop, the somewhat muddled picture wasn’t the hit the studio had hoped for. For Hollywood, this was more or less the end of the big budget SF movie until 2001: A Space Odyssey came along in 1968. Instead, Universal fell back on what did become a hit the same year, and which had worked well in previous films: mysterious monster menaces in smalltown desert settings, preferably made by the team behind Tarantula, writer Robert Fresco and director Jack Arnold.

This is how someone at Universal, he can’t remember who, came to Robert Fresco and told him to write a film about rocks that grow. Film historian Bill Warren suggests that someone on the Universal team had seen a demonstration of crystals that grow when they come in contact with water, and thought this was a good idea for a film. Fresco, at the time, was trying to get away from monster movies, and was pitching an idea to Universal with little luck, but since that wasn’t going anywhere, he decided to write a film about rocks that grow for $750, which was several months’ salary at the time. The film gives story credit to Fresco and Arnold, but Fresco says that the idea didn’t come from them. There was a standing agreement at Universal that Jack Arnold received story credit for the films he directed, regardless of whether he wrote anything or not. “A credit grabber”, Fresco called him. However, Arnold soon abandoned the project for a now-forgotten crime melodrama called The Tattered Dress, starring Jeff Chandler and Jeanne Crain. Universal instead brought in John Sherwood, a staff director who had made The Creature Walks Among Us (1956, review).

Fresco says that he struggled with the script, and finally left it for Norman Jolley to polish off. Jolley had SF experience from writing for the TV shows Space Patrol and Science Fiction Theatre. Fresco tells Tom Weaver that he had hoped that Jolley would have changed the script more – for the better. During pre-production the ending was changed. The original script was set by Salton Sea, and the ending would have had a small army of lorries transporting water from the saline lake, but the budget probably didn’t allow for such an undertaking.

While the writer may have thought The Monolith Monsters was “a terrible film”, it actually holds up rather well against everything else that was being made in the genre at the time. The script undoubtedly has its flaws. It starts a bit slow and it has a little too much padding. The characters are one-dimensional cardboard cutouts without any personality – with the exception of Les Tremayne’s smalltown newspaper editor, laconically commenting the proceedings, and functioning as a sort of moral compass of the movie. It’s difficult to buy that two accomplished geologists spend days experimenting on a rock sample without even once putting it in contact with water. Even little Ginny has the right idea here, washing her souvenire rock in a bucket before taking it inside. People die horrible deaths when coming into contact with the rocks, but long before he knows what makes it tick, Dave happily carries one around in his pocket, fiddling about with it every chance he gets. And so on – it’s not a particularly well-crafted script.

Tom Weaver laments that so much focus is put on the fate of little Ginny, while the world is theatened by the growing rocks. I disagree. The strength of The Monolith Monsters is that the threat is human-size. By focusing on the girl, the film gets an emotional anchor. And really, the movie is not about saving the world, but about saving a town. There’s a paradox about these kinds of movies that the more there is at stake, the less the audience cares. We all know that the Monolith Monsters are not going to destroy the Earth, so we don’t worry about that. But they may very well destroy the town – or kill a girl. That’s something we can invest in. Yes, the film also talks about the what happens if they don’t stop the rocks from growing and that they may threaten the world, but that’s actually unnecesary.

John Sherwood’s direction is competent but uninteresting. He creates a few atmospheric moments and is able to drum up sufficient tension, but lacks the sensitive, poetic touch of someone like Jack Arnold, even if the script occasionally veers off towards Arnoldish poeticism. The acting is competent across the board but only two actors stand out, Les Tremayne in his role as the newspaper editor, and SF veteran William Schallert in a short but funny cameo as a weatherman. Grant Williams was spectacularly good in Universal’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review), but has a nothing role to work with here. Lola Albright is fine, but she was better as a femme fatale than as an ingenue.

The film’s real treat are the special effects, as always well realised by Universal’s crack effects team. The shots of the black monoliths growing and crashing down over buildings and mountains are geniunely unsettling, and have been well filmed in slow-motion to give them a feel of gargantuan size and menace. The effects were realised by Frank Brendel, who later won an Oscar for his work on Earthquake (1975). Clifford Stine was in charge of the special effects photography. The growing effects are done through simple means – either by pushing the monoliths closer to the camera or by pushing them up through the surface of the miniature landscapes. Simple, but effective. I haven’t found any information what material the monoliths are made from, but it looks like some sort of resin, or perhaps fibreglass. Anyhow, they look very nice, and the effect of them shattering is highly realistic. The miniature models are well made, as usual with Universal, and the ending provides a an example of well-executed miniature flooding.

A shot of a meteor in the beginning of the film is reused footage of the opening shot of It Came from Outer Space – possibly magnesium or some other quickly burning material inside a spherical metal cage. William Alland had encouraged Universal to save money on effects costs by utilising stock footage – pointing to Columbia’s success with the same formula. The Monolith Monsters does use some stock footage of explosions, flooding and whatnot, but it is well incorporated into the film.

The soundtrack was put together from stock music by Joseph Gershenson.

It Came from Outer Space introduced the trope of inserting a monster/SF menace into a small desert town, creating a clash between sleepy, idyllic Americana and an element bringing change; a threat and uncertainty upsetting the comfortable life of the citizens. The trope was the handiwork of Ray Bradbury, who wrote the story for the 1953 movie, and it has seldom been as well executed as in that film. Them! (1954, review) replicated the formula with great success, and this made it stick. The Monolith Monsters also strives to set up the idea of a small town under siege from – something. However, the script never manages to give the threat a transferred, symbolic meaning. In the winged words of Robert Fresco, it’s just “rocks that grow”, in the same way as that the menace of The Deadly Mantis (1957, review) was just a giant preying mantis. When monsters of the early 50s were metaphorical in nature, warning either of a nuclear war or a communist invasion, the threats of late 50s SF films were largely devoid of any social, political or philosophical message. They were just monsters and growing rocks, conjured up for entertainment.

This makes The Monolith Monsters feel very much like the programmer that it is – based on the blueprints laid out by It Came from Outer Space and Them!. But this was Universal and not AIP. The movie is solidly made, and a screenwriter like Robert Fresco could turn out a functioning, even intriguing, script even on a bad day. There is something inherently spooky about the otherworldly monoliths growing out of the mountainside, threatening the lives of an entire town. The effects work is top notch, defying the film’s otherwise low-budget feel. And there is just enough personal drama to give the movie an emotional attachment. The film’s flaws are obvious, but out of the many late 50s SF programmers that were churned out of Hollywood in the era, this is certainly one of the better ones.

Reception & Legacy

The Monolith Monsters was released on December, 1958, topping a bill above Curt Siodmak’s Love Slaves of the Amazon.

With a few exceptions, the film received fair but uninterested reviews in the trade press. Harrison’s Reports noted the film “should prove acceptable whereever such pictures are enjoyed”. The magazine complained about too much technical jargon in the script, but said “the special effects work is good and helps considerably to build up suspense”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor wrote that the film “sustains interest fairly well, and the cast is adequate, as are the direction and production”. The Motion Picture Daily praised Grant Williams’ performance, and called The Monolith Monsters “produced with brisk efficiency […] and directed with equal competence”. Kove in Variety also complained about an over-abundance of technical mumbo-jumbo, but opined that the film was “better-made and more plausibly constructed than most [science fiction films]”. James Powers in the Hollywood Reporter was especially positive, calling it a “good picture, superior for its type”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy writes: “this simple but effective minor film has some extraordinarily good special effects by Stine. […] As a result The Monolith Monsters is a superior B movie, no more but certainly no less.”

In his book Keep Watching the Skies! (1997) Bill Warren wrote: “The Monolith Monsters is a decently made film with an interesting premise and some good effects. It isn’t a classic, but it is one of the better medium-budget SF films of the 1950s.” Phil Hardy in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies was also positive, calling it a “simple but effective minor film” with “some extraordinarily good special effects”, “a superior B movie, no more but certainly no less”.

Today, The Monolith Monsters has a good 6.3/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on a substantial 4,000 votes, giving credence to the film’s status as a minor classic. 1,800 Letterboxd users give it a 3/5 rating.

Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV Review writes: “The cast are great fun, deftly handling Robert M. Fresco and Norman Jolley’s jargon heavy script but the model work and effects photography, by Clifford Stine and and uncredited Frank Brendel are the real stars of the show”. Lyons calls the film a “solid if unremarkable addition to the American 50s science fiction cycle”. Joachim Boaz at Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations paraphrases the above-mentioned Phil Hardy in calling The Monolith Monsters “one of the more interesting films of the 1950s American Realist Science Fiction movement”. According to Boaz, “the most arresting quality of the film (besides the special effects) is John Sherwood’s creation of a small town ethos with a kaleidoscopic group of characters instead of concentrating solely on the two leads. […] Sherwood manages to enhance the isolation of the town and its resulting close-knit ethos with a bleak and isolated setting”. Richard Sheib at Moria Reviews gives the film a solid 3/5 stars, writing: “The finest moments are when we see the full-size rock monsters – the superb scene where Grant Williams and Trevor Bardette realise the implication of the rainstorm and rush out to watch as we see giant towering geodes, crashing and colliding as they grow, all silhouetted behind a ridge at night. It is a magnificently eerie intro of the monsters, one worthy of Arnold himself”.

Cast & Crew

John Sherwood was one of the many people who worked their way up in the film business, in his case from the props department to assistant and second unit director, in which capacity he made over 60 movies. He directed only three films, two of them science fiction: The Creature Walks Among Us (1955) and The Monolith Monsters (1957). Unfortunately the job led to his untimely death at just 55 years old in 1959, as he passed away from pneumonia contracted while directing the second unit on the film Pillow Talk.

Robert Fresco‘s first movie script was Universal’s SF hit Tarantula (1955), directed by Jack Arnold. Fresco had previously written a few TV scripts, but would continue to write horror/sci-fi films for Universal. In Tom Weaver’s book Eye on Science Fiction, Fresco says that he got into the business through cult producer Ivan Tors’ science fiction series Science Fiction Theatre (1955-1957), for which he wrote four scripts. One of them was called “No Food for Tought”, which was directed by Jack Arnold. Arnold liked the script so much that he asked Fresco to flesh it out into a full movie, and the result was the first draft for Tarantula.

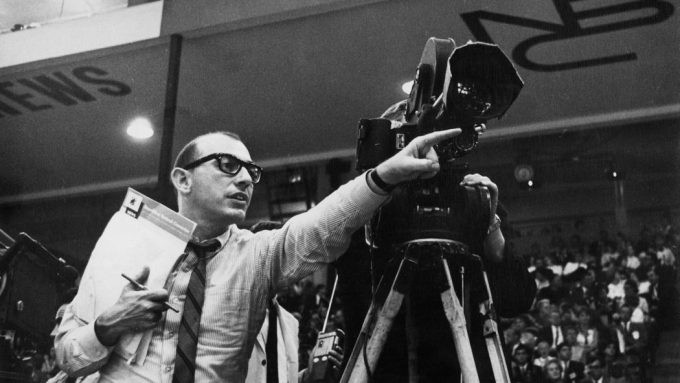

Fresco also wrote The Monolith Monsters (1957), which was one of the most original science fiction movies of the late fifties, and had a hand in The 27th Day (1957, review), The Alligator People (1959) and the Swedish-American co-production Space Invasion in Lapland (1959), also known as Invasion of the Animal People. In the sixties Fresco started producing and directing documentary films, and earned an Oscar for the movie Czechoslovakia 1968 (1969), a film documenting the history of Czechoslovakia between WWII and the Soviet invasion during the Prague Spring. Much of the film consisted of never before seen Czech stock footage, which had been smuggled out of the Communist country. Another praised production of his was the biographical film To Be Young, Gifted and Black (1972), retelling the life-story of Lorraine Hansberry, author of the play A Raisin in the Sun.

Born John Williams in 1931 in New York, lead actor Grant Williams served in the US Air Force between 1948 and 1952, and then returned to his hometown, where he got a degree in journalism, and studied acting under Lee Strasberg. He performed off-Broadway and had a few minor broadway roles, and a couple of TV appearances in New York, before relocating to Hollywood in 1955. After a few more TV shows, he was picked up by Universal, who groomed the handsome chap as a potential leading man. His first two films were directed by Jack Arnold. However, The Incredible Shrinking Man would remain the pinnacle of his career.

In the late 50’s Williams divided his time between TV and B-movies at Universal, often in the lead, but in small productions. His SF pedigree earned him leads in such films as The Monolith Monsters (1957) and The Leech Woman (1960). The latter was perhaps the last straw for Williams, who left Universal for Warner Bros. in 1960. His film career didn’t improve substantially, but he managed to carve out a little bit of recognition with a recurring role in the TV series Hawaiian Eye between 1960 and 1964. As his acting career dwindled, he opened a drama school. He continued to act in low-budget pictures after his contract with Warner ran out in the mid-sixties. In 1967 he starred in the notorious low-budget SF Doomsday Machine, but filming was interrupted when the money ran out. It was completed in 1972 or 1977 (accounts vary) without the original cast or sets. According to different sources, it was released either in 1972 or 1975 or 1977. Not much better was his lead in Al Adamson’s Brain of Blood (1971). After this, William called it quits on the movie business. He passed away in 1981.

Lola Albright arrived in Hollywood from Ohio by way of Chicago in 1947. A singer and model, she made her film debut the same year. Working her way up from uncredited parts to supporting parts, she also began to actively act on TV in the early 50s, and eventually started getting leads in B-movies. Her status as a prolific but perhaps not “profilic” actress came to an end in 1958, as she was cast as the sultry jazz club singer whose also the love interest of the title character in the noirish detective show Peter Gunn. Over the course of 114 episodes, Albright sang in 38, arranged by Henry Mancini. The show was a huge hit, and Albright became famous for her sultry demeanor and husky voice. In 1959 she was Emmy-nominated for her work.

Her role got her cast as a burlesque dancer who becomes involved in a romance with a teenage boy in the well-regarded low-budget movie A Cold Wind in August (1961), for which she received critical praise from both The New York Times and legendary critic Pauline Kael. Further high-profile roles as femme fatale followed, such as in the Elvis Presley vehicle Kid Galahad (1962), René Clèment’s Joy House (1964), Lord Love a Duck (1966) and The Way West (1967). For Lord Love a Duck she received the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. She retired from acting in 1968, and enjoyed a long retirement, passing away in 2017. The Monolith Monsters was her only SF movie.

Les Tremayne was primarily known from his radio work in the thirties and forties, when he appeared in some of the most popular radio dramas in the country. At one time he was voted one of the three most distinctive voices on American radio, alongside Bing Crosby and Franklin D. Roosevelt. At one time he appeared on 45 different shows in a single week. Tremayne plays the no-nonsense general Mann in The War of the Worlds (1953 review), one of the best military-type performances in a 50s SF movie.

Tremayne kept working in radio, TV and film up until the nineties, although in his later years he mostly did voice work. He appeared in numerous science fiction films: he narrated Forbidden Planet (1956, review), played one of the leads in The Monolith Monsters (1957) and did the rocket launch countdown for From the Earth to the Moon (1959, review). He played the lead in The Monster from Piedras Blancas (1959, review), and starred as one of the astronauts who land on Mars in Ib Melchior’s psychedelic cult film The Angry Red Planet (1959). He did numerous voices for the English dub of King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and had another starring role in The Slime People (1963). He guested an number of sci-fi TV series in the sixties and dubbed a role in the English version of Antonio Margheriti’s War Between the Planets (1966). One of Tremayne’s longest streaks in a single TV series was his role as Captain Marvel’s mentor in Shazam! (1974-1977). He did voice work on the 1985 animated movie Starchaser: The Legend of Orin, and, as mentioned, appeared in The Naked Monster.

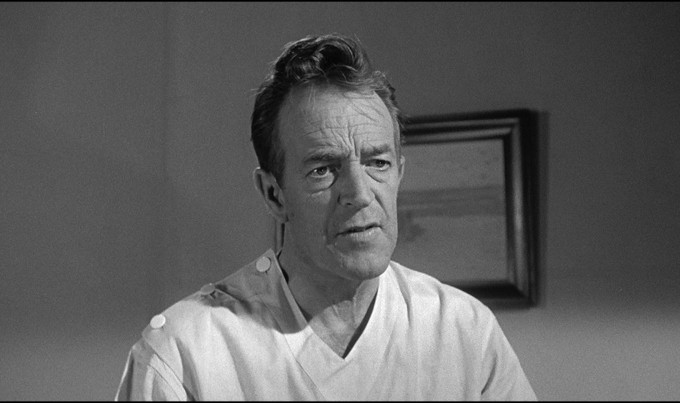

Trevor Bardette, playing the sympathetic professor in The Monolith Monsters (1957), probably relished in a reprieve from playing a villain. According to his IMDb bio, “his stoney features and deep-set, cold eyes ensured that he would invariably be cast as a ruthless heavy, sneaky spy, swindler, gangster or double-crosser”. A prolific character actor, he appeared in close to 300 films, serials or TV shows between 1937 and 1970, small parts in prestige films and bigger parts in serials and smaller films. His only other SF outing was an uncredited appearance in Flight to Mars (1957, review).

Phil Harvey was a Universal contract player who appeared in close to 20 films between 1956 and 1958, including three science fiction movies in 1957: The Deadly Mantis, The Land Unknown (review) and The Monolith Monsters. His last three roles at the studio were uncredited but parts, and he struck out as a freelancer in 1958. Harvey appeared in two AIP movies, Monster on the Campus (1958, review) and Why Must I Die (1960), and had a couple of TV guests spots. He called it quits in 1961 and became a music teacher, and later set up a camera shop.

The rest of the cast is made up by Universal contract players and other character actors, such as legendary voice artist Paul Frees, stuntman and monster actor Eddie Parker and well-respected SF staple William Schallert, as well as well-known news anchor Jerry Dunphy. Then there’s the newspaper boy, played by Paul Petersen, who would go on to nationwide fame as one of the stars of The Donna Reed Show (1958-1966).

Richard Cutting was a well-employed bit-part player, mostly in westerns, from the early fifties until his death in 1972. However, to Americans of the boomer generation he is probably remembered primarily as Manners, the tiny butler, in a series of tv ads for Kleenex table napkins, the ones that “cling like cloth. Thank you”. He also had a supporting role in Roger Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957, review).

Troy Donahue experienced 15 minutes of fame as a blonde heartthrob in Warner’s A Summer Place (1959), Parrish (1961) and Palm Spring Weekend (1963). However, his career decline in the mid-60s, and he went freelance, soon playing supporting parts in AIP movies and getting by on TV guest spots. However, he kept at it and appeared in films large and small throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s – from a bit-part in The Godfather: Part II (1974) and a supporting role in Cockfighter (1974) to halfway decent movies like Gradview, U.S.A. (1984) and Deadly Prey (1987) and cult classics like Cry-Baby (1990), all the way down to clunkers like Nudity Required (1989) and Sexpot (1990). He appeared in a number of SF movies: The Monolith Monsters (1957) Monster on the Campus (1958), Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon (1967), Cyclone (1987), The Drifting Classroom (1987), Dr. Alien (1989) and Omega Cop (1990).

Producer Howard Christie would go on to become the showrunner on the TV show Wagon Train between 1958 and 1965. DP Ellis Carter had also shot The Incredible Shrinking Man, and won an Emmy for The Alphabet Conspiracy in 1959. Universal’s head of the art department Alexander Golitzen is credited for art direction, but most of the work was probably done by Robert Emmett Smith who was nominated for an Oscar for King Rat (1966).

Janne Wass

The Monolith Monsters. 1957, USA. Directed by John Sherwood. Written by Robert Fresco, Norman Jolley. Starring: Grant Williams, Lola Albright, Les Tremayne, Trevor Bardette, Phil Harvey, William Flaherty, Harry Jackson, Richard Cutting, Linda Scheley, Dean Cromer, Steve Darrell, Claudia Bryar, Troy Donahue, Jerry Dunphy, Paul Frees, Eddie Parker, Paul Petersen, William Schallert. Cinematography: Ellis Carter. Editing: Patrick McCormack. Art direction: Alexander Golitzen, Robert Emmett Smith. Costume design: Marilyn Sotto. Makup artist: Bud Westmore. Sound: Leslie Carey. Special effects: Clifford Stine, Frank Brendel. Produced by Howard Christie for Universal.

Leave a comment