Scientists accidentally blow a hole in the ionosphere, resulting in visiting aliens and giant bugs. This 1958 UK low-budget production has some good ideas, but is hampered by equally bad ones. 4/10

The Strange World of Planet X. 1958, UK. Directed by Gilbert Gunn. Written by Paul Ryder. Based on novel by Rene Ray. Starring: Forrest Tucker, Gaby André, Martin Benson, Alex Mango. Produced by John Bash & George Maynard. IMDb: 4.8/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Single-minded scientist Dr. Laird (Alec Mango) is working on secret experiments with magnetic fields in his lab outside a small village in Souther England. Assisting him are American Dr. Gil Graham (Forrest Tucker) and new assistant, French Michele Dupont (Gaby André) who is – gasp! – A WOMAN!

When it turns out that Laird’s experiments may have fantastic applications for the British military, they become closely monitored by govermnment officials Jimmy Murray (Hugh Latimer), Gerald Wilson (Geoffrey Chater) and Brigadier Cartwright (Wyndham Goldie). Nevertheless, when it becomes clear that the magnetic rays affect objects far outside of the lab, Gil, Michele and the G-men become worried. At the same time, flying saucers are reported in the press, and one day, a mysterious Mr Smith (Martin Benson) shows up in the forest outside the village.

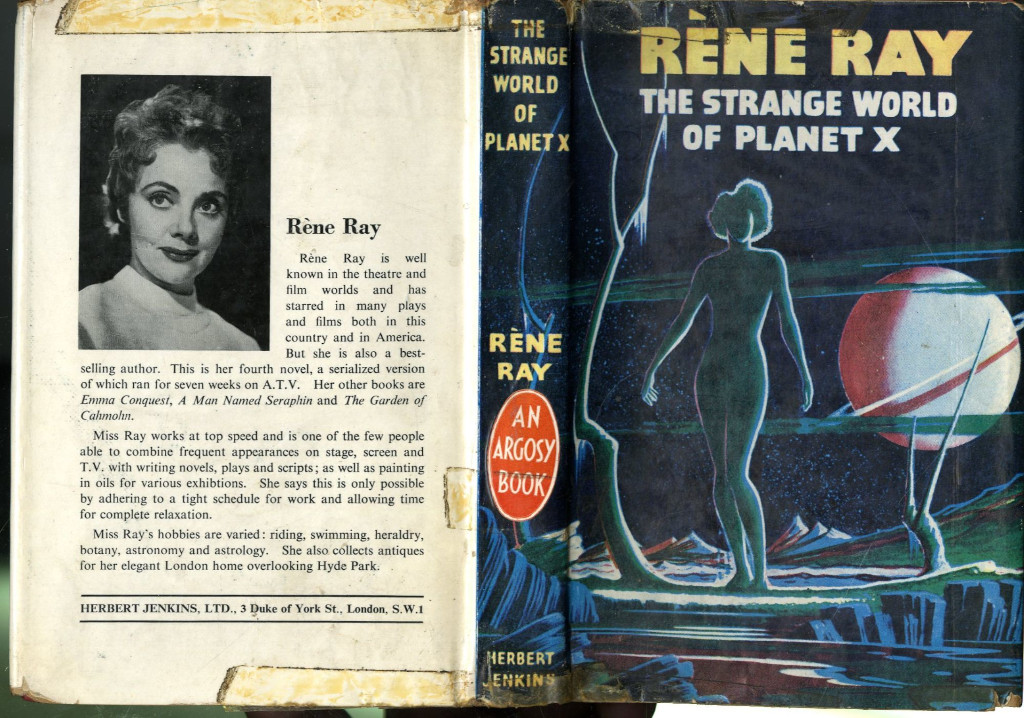

That’s the build-up to Gilbert Gunn’s British 1958 low-budget SF thriller The Strange World of Planet X. The film was loosely based on a 1956 TV series with the same name, and the novelisation of said series, both penned by Rene Ray, Countess of Midleton, an actress, singer and author. However, the script for the film, written by Paul Ryder, differs significantly from the source material. The movie was released in the US under the title The Cosmic Monsters, on a double bill another British import also distributed by Eros Films, and also starring Forrest Tucker, The Trollenberg Terror (1958, review), re-christened for US markets as The Crawling Eye.

Strange occurrances … occur … in the village: the pub TV keeps breaking down, there are freak thunderstorms and gales, and a previously harmless bum starts killing women in the woods, before he is himself found dead with mysterious radiation burns. Gil and the G-men fear that new additions to Laird’s apparatus causes it to enormously amplify its power through a feedback loop, possibly endangering the neighbourhood – but are afraid to take up these matters with the single-minded Laird, fearing his reaction. One night, Mr. Smith overhears the party’s conversation about Laird’s experiments at the local pub, and strikes a meeting with Gil and Michelle. Here, he refuses to say who he is or where he comes from, but explains that Laird’s experiments are warping the ionosphere, causing radioactive rays from outer space to reach Earth, which might drive people mad and even kill them (like the hobo), and might cause mutations in smaller animals, like insects – they might grow to enormous size.

Of course, you can’t have a Chekhov’s giant insect hanging in the air without materialising it, and soon all sorts of giant critters start milling about the local school, trapping new teacher Helen Forsyth (Patricia Sinclair) inside. Michelle rushes to the rescue, but is trapped by a giant spider’s web, which leaves her and Helen awaiting the arrival of the cavalry, namely Gil, Jimmy and Mr. Smith. Smith pulls out a strange gun and kills the spider, and both women are saved.

Later, Smith explains that he comes (surprise, surprise) from a distant planet, one which the tabloid press has named “Planet X”, and that they have been monitoring Earth for a long time. He is here to warn Earth about Laird’s experiments, which are not only dangerous for Earth, but also upsets Earth’s magnetic field, which the aliens’ flying saucers are using for navigation when watching over the planet. He also tells the Earthlings that the aliens have now neutralised all giant insects. Upon learning all this new information, Gerald races to Laird’s lab, intending to close down the experiments. But Laird will not hear of it, and shoots Gerald. However, before dying, Gerald manages to phone for help. The G-men, Gil and Michelle arrive with Mr. Smith. Smith explains that ge can blow up Laird’s lab with Laird inside, but the decision must be taken by the Earthlings present: to sacrifice the life of one individual for the sake of the common good…

Background & Analysis

The background of The Strange World of Planet X spells Irene Creese, who was a British actress, singer and writer, going under the artist name Rene Ray (pronounced Reen as in Irene, not René, as her IMDb bio erranously states). In the mid-50s Ray left a fairly sussessful acting career behind her to focus on her writing. By this time she was already an accomplished novelist. In 1956 she penned the script for the ATV television series The Strange World of Planet X, which must have been at least moderately popular, as she novelised it in 1957. According to most sources, it consisted of seven episodes, however, Andy Gryce writes that there were six 25-minute episodes (IMDb also lists six episodes). British TV stations were notoriously unsentimental about their early TV shows, and the series has not survived. However, according to “Sergio” at Tipping My Fedora, Ray’s novelisation seems to follow the outline of the TV series rather closely.

The same thing can not be said about the film, which was adapted by Paul Ryder. The novel does not feature an alien visitor, flying saucers or giant insects, which are all the focus of the film (Andy Gryce suggests that Ray added these elements to the novel, but that seems to be conjecture on his part. I have not seen any evidence of this in any plot descriptions.). By all accounts an at least slightly more intelligent production, the series, as the book, focused mainly on the relationship between the two scientists, Laird and Graham. As in the film, Laird wants to press on with his experiments regardless of the dangers, while Graham, worried about the powers they are dealing with, tries to slow down, leading to a game of cat-and-mouse where both scientists try to sabotage each other. Caught in the middle is Laird’s wife, who grows ever more worried about the cold and ruthless side emerging in her husband. However, in the book and the TV show, Laird and Graham accidentally open up a portal to a fourth dimension, and are transported to the “abstractly arid” Planet X, where space and time converge.

As Gryce has actually seen the TV show as a kid, I’m going to quote him at length: “Scientists discover a formula giving access to the fourth dimension – the unification of time and space – and, with others, are transported to the abstractly arid Planet X. It presented the fairly cerebral concept of the fourth dimension and time travel in an engrossing way that held the attention of audiences for nearly two months on the fledgling network, this at a time when there were only a relatively small number of television sets in England. I can remember watching the programme and feeling scared as the scientists stared through a screen into a dark experimental chamber where some frightening transformation was taking place.”

Apparently, independent producers George Maynard and John Bash were not as interested in recreating the TV series or the book as they were in making a film containing the popular tropes of Hollywood science fiction movies. The friendly but mysterious alien is, of course, ripped from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), and at the time giant bugs were all the rage of the other side of the Atlantic. The main character, Graham, was turned American, because of the involvement of Hollywood star Forrest Tucker, and Laird’s wife was turned into French assistant Michele, because of the involvement of Gaby André.

The Strange World of Planet X was distributed by Eros Films, a distributor, financer and production company that specialised in distributing and co-financing small, independent British films, that it often released as second features alongside US imports. Eros had a deal with American ARC to distribute some of its movies overseas, and for this they applied the usual arrangement, that the British B-movies needed to feature a recogniseable American star. For The Strange World of Planet X, that star was Forrest Tucker, a seasoned character and occasional lead actor, known for combining a calm, underacting style with a jovial demeanor. Tucker is the calm center of the film, but somewhat miscast as what one critic called a “middle-aged Lothario”. The age difference between him and Gaby André is seemingly so big that the scene in which Graham grabs and kisses his young colleague feels quite awkward (although this is more due to the manner in which he grabs her, rather than the age difference). In reality, Tucker was only 39 when he did the role, but looks like his going on 60. André, on the other hand, was 38, but could easily be mistaken for 28. André, a star of French and Italian movies, seems to have been brought to the UK expressively to star in The Strange World of Planet X. However, despite the fact that she plays a French woman, her accent was deemed to grave, so she was dubbed by a British actress – with an affected French accent.

While nominally the lead, Tucker’s role is not really a traditionally heroic SF movie lead, as the film is more of an ensemble play. The most memorable character is that of the mysterious Mr. Smith, who turns out to be the true hero of the piece. The character is quite well written and superbly played by Martin Benson. Like Michael Rennie in his memorable role as Klaatu, Benson plays the alien in a sort of aloof, yet humble and bemused manner. He is otherworldly enough to be slightly menacing, but his meeting with a small girl in the forest (Susan Redway) upon first arriving, also suggests that he cares for the people of Earth, and he shows a propensity for kindness and humour. The supporting cast is all very Britishly good, with short, stocky Geoffrey Chater and thin, gaunt Hugh Latimer standing out. Speaking of actors not looking their age, by 37 Chater had already lost most of his hair.

The Strange World of Planet X was directed by Gilbert Gunn, primarily a playwright and theatre producer, who started working as a screenwriter in the thirties, and began directing shorts after WWII, graduating to feature films in the early 50s. He had no experience with horror or SF when embarking on The Strange World of Planet X, and directs with no discernable style, other than emulating the tone of both the Quatermass films and American science fiction movies. The sets are cramped, and the outdoor location shooting does little to alleviate the feeling of a low-budget movie, as it is mostly done in limited static shots. For example, there is the usual sign of a low-budget movie, that there is no sense of geography. The lab is supposedly a good way away from town, but we move to a from it as if it were next door to the pub. Curiously, the school is also located in a remote wooded area, and a bus stop features heavily in the movie, but they both still seem to be within walking distance from everything else. Sets and locations are limited, for example the same small stretch of wooded path is reused several times, and the lab seems to have only one wall.

The movie builds rather nicely as a subdued, very British mystery thriller, concerned more with red tape and philosphical ruminations on the ethics of science than with the UFOs and aliens. Mr. Smith is the mysterious presence that the viewer is compelled to unravel. As per usual in British low-budget SF films, most important revelations are made over a pint of beer at the local pub. The mad scientist’s experiments messing with the pub TV reception seems to be more of an inconvenience that the hole they’re punching in the ionosphere. Screenwriter Paul Ryder’s view of women is appaling, all male scientists exclaim “Preposterous!” when it turns out that the new computer expert is a woman, and the romantic subplot is as badly written as it is redundant.

Despite the film’s flaws, it has a nice air of mystery and moves along at a decent pace, spurred on by adequately interesting themes and plotting and decent acting. But as British critic Robin Bailes puts it at Dark Corners: then the giant bugs arrive. This is a film that did not need giant bugs, that is not made any better by giant bugs, and that in no way really revolves around giant bugs. But despite this, the producers hade decided to make giant bugs the climax of the movie. While the bugs are decently filmed, sometimes in natural surrondings, sometimes on a miniature set, they unfortunately never feel like giant bugs, because Gilbert Gunn doesn’t understand to overcrank the camera in order to give them slow-motion movement. As it is, they simply feel like ordinary bugs. That said, there are a couple of creepy bug moments in the film. But overall, the whole bug business feels like it’s been crammed into the wrong film because someone thought it was a good exploitation idea to have giant bugs in the movie that has nothing to do with giant bugs.

As to realism or scientific accuracy, this is a movie about someone conducting metallurgical experiments which bors a whole in the ionosphere, causing space rays to mutate insects into giant monsters and upsets the magnetic fields which UFOs use to navigate Earth. I don’t feel any pressing urge to pick holes in its scientific accuracy or logic.

Neither is this a film with a clear topic, theme or moral. There is a benevolent alien, which usually represented a counterpart to the red scare movies which equated evil aliens with either Soviet invaders or domestic communists in the US. Benevolent aliens usually represented a voice for peace and mutual understanding. Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still was expressively meant to represent the UN, as the filmmakers were arguing for a more powerful UN mandate. However, The Strange World of Planet X doesn’t deal with international strife or the cold war. The only war referenced here is the one between the sexes. There is a theme here about the philosophy of science, but feels more like an artefact from the source material than a theme taken seriously, as it is too caricatured to be taken seriously. Laird’s sudden turn into madman simply feels tacked in order for the film to have a dramatic climax. Once the giant bugs enter the picture, all of the subtlety and build-up goes out the window and the film becomes one dramatic episode after the other with little logic or coherence.

The film’s British title deliberately refers to its inspirations like The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review) and X the Unknown (1956, review), revelling in the formerly dreaded X rating given out by British censors. In the US this would have meant little, as the Quatermass films were all retitled in America, and of course, the X rating did not exist in the US. In Rene Ray’s original series, The Strange World of Planet X referred to the fourth dimension opened up by Laird and Graham. Of course, in the film, the title seems like misnomer, as there’s no reference to a strange world on another planet, or indeed another dimension. Screenwriter Paul Ryder deftly deflects this by having Mr. Smith state that the aliens have been watching Earth from some time, and that “the strange world of Planet X” is actually Earth.

The Strange World of Planet X retains some of the intrigue, mystery and intelligence of its source material, which makes it, at least for its first two thirds, a mildly entertaining mystery thriller with SF trappings. The understated acting is fairly good and it has some fun, very British humour. The romantic subplots, on the other hand, are poorly written and wholly unnecessary. The film’s third act just feels like a misguided attempt to emulate popular Hollywood movies and unfortunately sinks the movie. The film is most interesting for its backstory as the first British SF TV series written by a woman. It’s just too bad that her story was not brought to the big screen.

Reception & Legacy

The Strange World of Planet X bombed at the box office both in the UK and the US. In the US it was for a time released on a bouble bill with The Trollenberg Terror, also re-titled, as The Crawling Eye. There’s some confuction over the title, as the promotional material had the erranous title “Cosmic Monsters”, which is also the title under which it was released on VHS, and one critic referred to the film as “The Crawling Terror”, but that was most likely just a mistake. The film fared poorly in movie theatres, but distributor ARC had better luck with it at the drive-in circuit.

The New York Times critic Richard W. Nason noted that “The Crawling Eye and The Cosmic Monster do nothing to enhance or advance the copious genre of science fiction”. Rich at Variety called the film “a singularly uninspired potboiler” and a “plodding affair”. According to the paper, the dialogue veers between “scientific jargon and coy flippancy”, and the special effects were not deemed particularly good. Martin Benson, however, was singled out for his good performance.

In his book Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren laments, in opposition to most critics, that there’s too little bug action in the film: “it’s boring at the beginning, only briefly exciting when the bugs attack, and overall predictable”. Another critic wishing for more insect excitement is Bryan Senn, calling the first half of the movie “unfocused”, saying it consists of “little more than dull palaver […] alleviated only by the amusingly over-the-top sexist dialogue”. Phil Hardy writes in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies: “The film’s poor effects make the insects look ludicrous and set the seal on an already plodding screenplay”.

Today, The Strange World of Planet X has a 4.8/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on around 1,400 votes, and a 2.8/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on 600 votes.

AllMovie gives the film 2/5 stars. Bruce Eder, in an unusually poorly researched review (he claims the book predated the TV series and that the series’ producers were the same as the film’s), writes: “The problem with the movie lay in its subsequent production and the approach of the director, Gilbert Gunn, who, between a pitifully low budget and a production for which the word “spartan” was an understatement, could not make much of the story, in terms of moving it along or coming up with an effective suspense pacing. The film has atmosphere in many of the right spots, but it looks painfully threadbare in almost every shot — the makers utilized a studio facility that was mainly used for commercials — and none of the cast, even visiting American star Forrest Tucker, seems able to find a groove for their work, or any kind of rhythm or pacing. The final piece of the puzzle that fails the production is the special effects, the giant insects that populate the last section of the movie, which are among the least convincing shots of their kind from this era.” Likewise poorly researched is the review from TV Guide, which claims the film was based on a BBC TV series, rather than ATV. TV Guide calls the movie “pretty silly stuff”.

Richard Scheib at Moria Reviews states that the film “has a reputation as a bad movie, although aside from failings in the special effects department that kill it in the latter half (see below), it has a routine competence for the most part”. Schieb gives the movie 1.5/5 stars, continuing: “It is however the utterly inadequate special effects that do the film in. To represent the giant monsters, the production has opted for the good old B movie standard of optically enlarged insects. What we end up with looks precisely like a series of badly inserted praying mantises pretending to attack people. The UFO that appears at the end also had a clearly visible wire holding it up. One of the more amusing aspects in seeing the film today is its quaintly dated sexist attitudes – like when the idea of the scientists getting a female lab assistant is greeted with lines like ‘A woman? This is preposterous. This is highly skilled work.’”

If the film has one real distinction, it is that this is the only British film to venture into giant bug territory in the 50s.

Cast & Crew

Scottish-born Gilbert Gunn (1905) began his career as a playwright, composer and theatre producer, before starting to dabble in screenwriting in the late 30s, although he wrote only a handful of scripts before WWII, when he was drafted to write information and propaganda shorts. He returned again to feature films as a screenwriter in 1949, with the war film Landfall, directed by future Oscar nominee Ken Annakin. In 1952 Gunn was entrusted to compile the anthology documentary Elstree Story, commemorating the studio’s 25th anniversery. So impressed was the company behind the studio, ABPC, that it hired him to direct two comedies in 1953. He returned to directing in 1956, and between this year and 1959, directed a handful of fairly popular B-movies in different genres, leaning toward comedy. He directed two more small films and a TV series in the early 60s, but was overrun by the wind of change in the movie business in the 60s, and was relegated to filming documentaries on golf. He passed away in 1967, only 55 years young. The Strange World of Planet X was his only SF entry.

Little is known about screenwriter Paul Ryder, who wrote five scripts for minor pictures between 1957 and 1963.

American lead actor Forrest Tucker started as a singer and comedian in vaudeville in his teens in Chicago, and worked on stage in Washington, D.C. at a young age, before travelling to Hollywood in 1940, where he got was cast mainly for his burly physique, and became a mainstay as a brawler or henchman in westerns. However, he soon got to show his comedic timing in the lead of the screwball romcom Emergency Landing (1941), for PRC, which won him a contract with Columbia. Columbia provided mainly supporting roles, for some of which he was borrowed by major studios, and in 1948 he jumped ship to Republic, which thanked him with a few starring roles, two of which came at Paramount. In the early 50s he also made his first of several films in England, as a Republic co-production. He had starred in the TV series Crunch and Des in 1955-1956 and returned to the big screen with a top billing in Fox’s The Quiet Gun (1957), before heading back to England to shoot The Abominable Snowman (1958), The Strange World of Planet X (1958) and The Trollenberg Terror (1958). The same year, he had a role in Auntie Mamie, the highest grossing film in the US in 1958.

1958 also saw Tucker return to the stage for a national touring production of The Music Man, which he performed over 2,000 times over the next five years, and followed up with work on Broadway in 1964. He was then cast as Sgt. Morgan O’Rourke in the popular TV show F Troop (1965-1967), which is the role he is probably best remembered for today. After this, he continued acting in film and TV as a sought-after character actor, with the occasional lead sprinkled in, such as in the short-lived comedy/SF TV show The Ghost Busters (1975) and the science fiction/action movie Thunder Run (1985). His last performance was in the science fiction TV movie Timestalkers (1987).

Gabrielle “Gaby” Andreu, later Gaby André, entered the French movie business at the age of 16 in 1936, and had bit-parts in G.W. Pabst’s Four Flights to Shanghai (1938) and Abel Gance’s Paradise Lost (1939), and had a rather unspectacular but busy career throughout the 40s, until she met American industrialist Eli Smith and married in him in 1947, which led to a four-year hiatus from the screen, as the couple settled in Italy. In 1950 André took a stab at Hollywood but then returned to Italy, where she started appearing in both smaller roles and leads such as in the comedy The Sleepwalker (1951) and costume dramas such as Giuseppe Verdi (1953). In the 50s André altered between French, Italian, British and American movies, appearing, for example, in Rudolph Maté’s The Green Glove (1952) opposite Glenn Ford and the British low-budget science fiction film The Strange World of Planet X (1958). In the 60s she appeared in a number of spaghetti movies, sometimes in the capacity of leading lady, such as in Goliath and the Dragon (1960) and Duel at the Rio Grande (1963). And in 1970 she appeared in a supporting role in Woody Allen’s Pussycat, Pussycat, I Love You, filmed in Rome, which was her second-to-last role, as she passed away in 1972, only 52 years old.

Martin Benson was a noted character actor in both American and British films with a career spanning six decades, as well as a noted stage actor. He is particularly well known for his role as Kralaholme in the 1953 London premiere of the musical The King and I, which he played for almost 1,000 performances, and reprised in the 1956 Oscar-winning film. Because of his dark and somewhat unusual features, Benson was often cast as villains, not seldom Arabs. One of his best remembered roles is that of the henchman Mr. Solo, who gets killed by Oddjob in the James Bond film Goldfinger (1964). His roles were often small, but memorable, such as Mordekai in Otto Preminger’s Exodus (1960), Ramos in Cleopatra (1963), Maurice in the Clouseau movie A Shot in the Dark (1964), Father Spiletto in The Omen (1976) and Abu-Jahal in The Message (1976). He also played a Vogon Captain in the 1981 adaptation of A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. The Strange World of Planet X (1958) gave him one of his very few starring roles. He also appeared in Gorgo (1961) and Battle Beneath the Earth (1967).

The actor playing the mad scientist in The Strange World of Planet X (1958) goes by the delicious name of Alec Mango. Mango was also a sought-after character actor in both UK and US films, best known for playing El Supremo in Captain Horation Hornblower (1951) and the Caliph in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). He also had a bit part in Frankenstein Created Woman (1967).

The rest of the cast is made up of recogniseable British character actors such as Dandy Nichols, known in the UK for co-starring in the comedy series Till Death Do Us Part (1965-1975), Geoffrey Chater, who turned up as authority figures in numerous films, such as Barry Lyndon (1975) and Gandhi (1982) and Hilda Fenemore, remembered for small but poignant turns in a number of Carry On films.

Rene Ray was the artist name of Irene Creese, a successful actress and singer on stage and screen through the 30s and 40s. She made her screen debut in the 1929 science fiction epic High Treason (review), in an uncredited role. She had numerous starring roles in minor films throughout the 30s, including Michael Powell’s musical Born Lucky (1933), the science fiction movie Once in a New Moon (1933, review), The Passing of the Third Floor Back (1934), opposite Conrad Veidt, and Maurice Elvey’s Return of the Frog (1938). She appeared in smaller roles in bigger films, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Secret Agent (1936), Alberto Cavalcanti’s They Made Me a Fugitive (1947) and Lewis Gilbert’s The Good Die Young (1954). Had she won the lead in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), which she auditioned for, Ray’s career might have taken a different turn, however, she stayed in London, and during most of WWII, performed on stage in West End. In 1947 she got good reviews when performing in the Broadway premiere of J.B. Priestley’s classic An Inspector Calls. That same year she appeared in her only Hollywood film, in a supporting role in Victor Saville’s If Winter Comes (1947).

However, by the mid-1940s she also started focusing on writing. Her debut was a gothic fantasy called Wraxton Marne, published in 1946, by all accounts moderately successful, and her next novel, Emma Conquest (1950), was a “bestseller”, according to one source. In 1956 she wrote the teleplay for the science fiction mini-series The Strange World of Planet X for commercial TV station ATV, becoming the first woman to write an SF series for British TV. The story follows Dr. Laird, who, along with colleague Graham, opens a portal to a fourth dimension (Planet X), where he starts sending people who try to warn him about the dangers of his experiment, including his own wife and colleague. Ray novelised the series in 1957, and it was turned into a low-budget film in 1958, albeit with a very different plot. All in all, Ray published seven novels, the last one, a fantasy called Angel Assignment, in 1988. She dropped out of film acting in 1957, partly due to diminishing roles. In 1975 Ray married George St John Brodrick, second Earl of Midleton, giving her the title Countess of Midleton. She passed away in 1993.

Composer Robert Sharples was a bandleader, composer and arranger, best known in the UK for being the bandleader for the long-running talent show Opportunity Knocks (1964-1978). He composed the theme music for several TV shows, and worked on many films and TV series. Several of his brassy, jazzy compositions are still in frequent use in films and TV shows to this day, such as Spy Hard (1996), SpongeBob SquarePants (2002-2015), Malevolent (2018) and Albert Brooks: Defending My Life (2023).

Visual effects artist Les Bowie was one of the greats in British effects and matte work, working on everything from The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) to Superman (1978), for which he won both a BAFTA and an Oscar.

Janne Wass

The Strange World of Planet X. 1958, UK. Directed by Gilbert Gunn. Written by Paul Rider. Based on the novel The Strange World of Planet X by Rene Ray. Starring: Forrest Tucker, Gaby André, Martin Benson, Alex Mango, Wyndham Goldie, Hugh Latimer, Dandy Nichols, Richard Warner, Patricia Sinclair, Geoffrey Chater, Hilda Fenemore, Susan Redway. Music: Robert Sharples. Cinematograpy: Josef Ambor. Editing: Francis Bieber. Art direction: Bernard Sarron. Makeup: Charles Nash. Visual effects: Les Bowie. Produced by John Bash & George Maynard for George Maynard Productions & Artistes Alliance.

Leave a reply to Bill Ectric Cancel reply