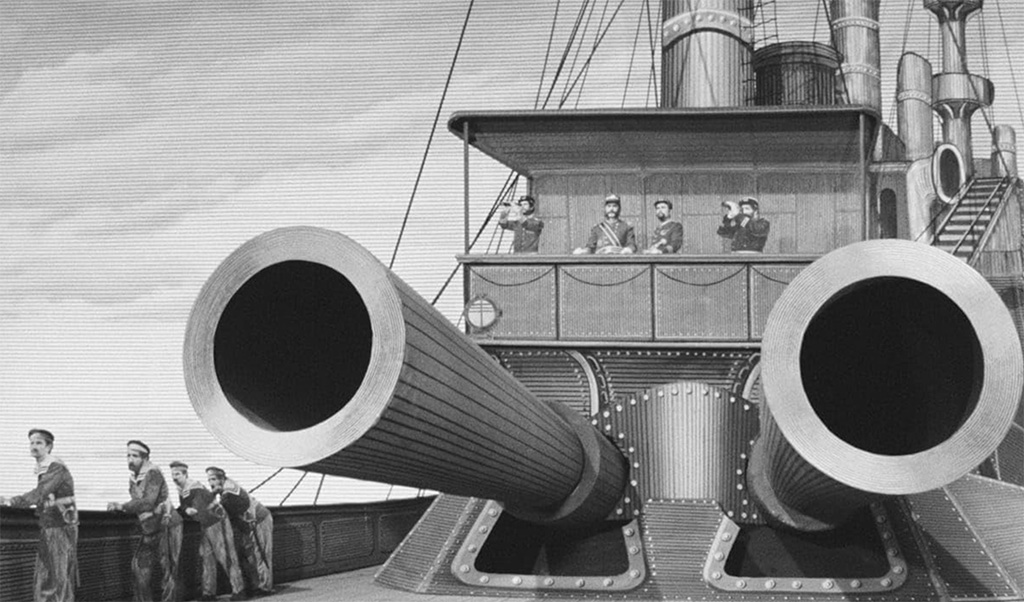

Submarines, Bond villain bases and superweapons all play into the plot of Karel Zeman’s 1958 cult classic, based on Jules Verne. But it is the spectacular blend of animation, artful sets, mattes and live action that makes this whimsical and funny fairy-tale so enjoyable. 8/10

Invention for Destruction. 1958, Czechoslovakia. Directected by Karel Zeman. Written by Karel Zeman, Frantisek Hrubin, Milan Vacha. Based on novel by Jules Verne. Starring: Lubor Tokos, Arnost Navrátil, Miroslav Holub, Jana Zatloukalová. Produced by Zdenek Novák. IMDb: 7.5/10. Letterboxd: 3.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 8.5/10. Metacritic: N/A.

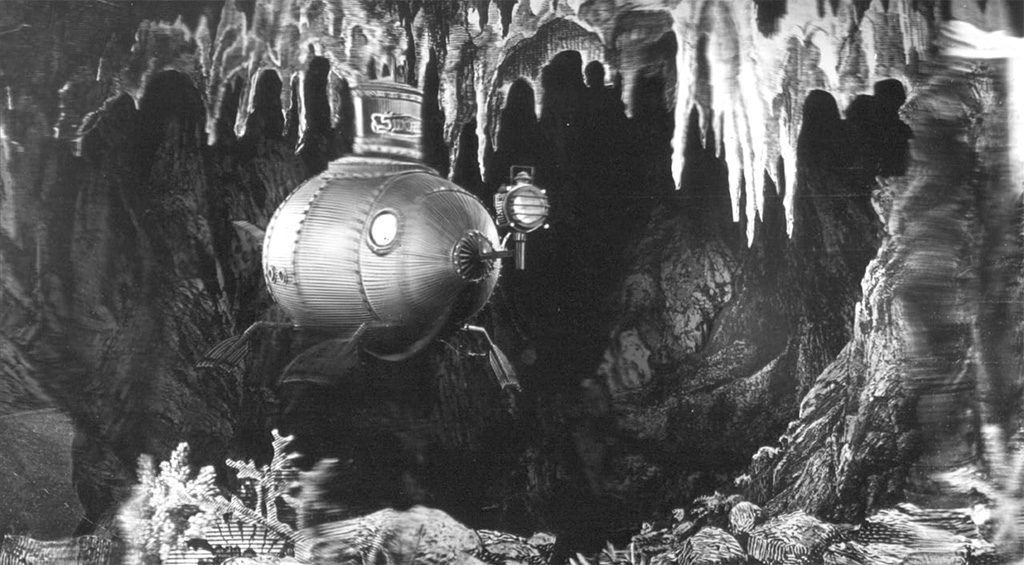

Young and idealistic Simon Hart (Lubor Tokos) travels across Europe, marvelling at the wonders of science and progress: trains, airships and submarines. Truly, the inventions of the future will sweep away the follies of yesterday! At his destination, a castle by the sea, Hart meets his old friend, Professor Roch (Arnost Navrátil), whom he is to help with his latest invention: a new technology unleashing endless energy by tearing apart the atoms themselves. However, one stormy night, the two are kidnapped by a pirate captain (Frantisek Slégr), and taken aboard his ship – a ship that is being towed by a submarine. Both belong to Count Artigas (Miroslav Holub) – a civilised but ruthless villain who keeps Prof. Roch as an unwitting prisoner by convincing him that he means to finance his research into peaceful technology. In reality, Artigas means to steal the technology in order to create a giant super-cannon and become the ruler of the world.

So begins the 1958 Czech film Invention for Destruction, or Vynález zkázy, which was originally released in the US by Warner as The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, with an English dub and a new prologue. The film was the creation of legendary director, animator, special effects creator and art director Karel Zeman, and sports a magnificent, fairy-tale like look imitating the wood engravings and linotypes that illustrated the original Jules Verne book releases. So magnificent are the visuals of the film that the plot is really secondary. But still:

On the way Artigas’ secret James Bond-styled island lair, “Back Cup”, the submarine sinks a merchant vessel, picking up the lone survivor, Jana (Jana Zatloukalová). At the island, Hart is kept in isolation and is thus unable to warn the well-meaning but far too trusting professor that Artigas means to exploit his invention for nefarious means. He tries to have Jana smuggle a letter to Roch, but the absent-minded professor loses it to a gust of wind before he has a chance to read it. Labouring away in his rickety hut on the side of the volcanic crater, Hart is able to construct a hot air balloon, with which he sends a letter of warning to the outside world. Soon, the major powers of the world unite against Artigas and his diabolic weapon, and send a fleet to destroy him. But by this time Artigas has perfected his cannon, and is poised to wipe out his puny enemies…

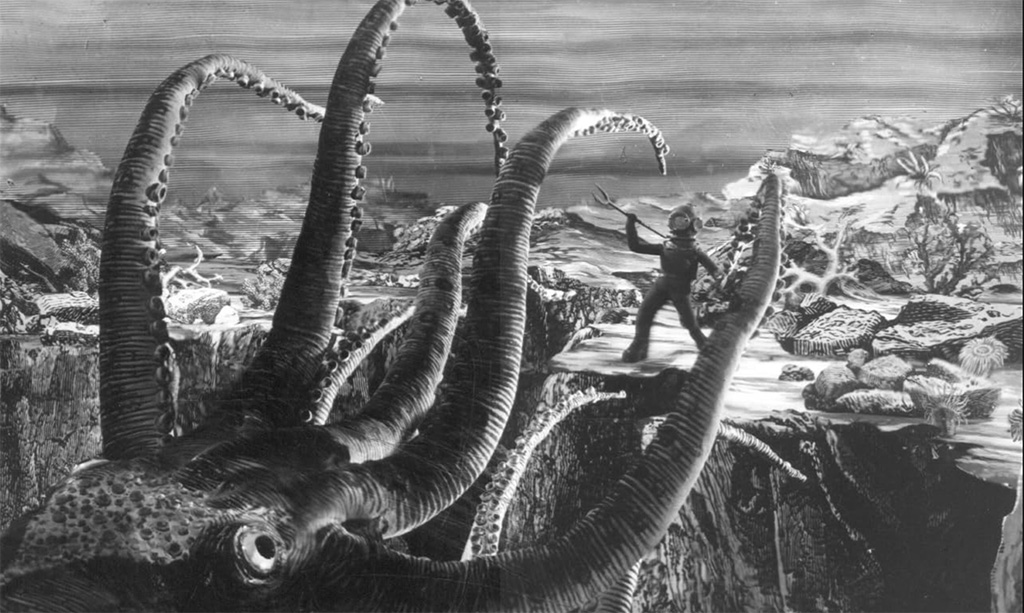

Along the way to the climax, in which Prof. Roch makes a heroic sacrifice, there are also several fun and dramatic incidents, such as an underwater treasure hunt, a battle between submarines and encounters with both a shark and an octopus.

Background & Analysis

In some sources there is some confusion over which of the works of Jules Verne Invention for Destruction is based on, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1870) is a suggestion that turns up here and there. And while there are bits and pieces in the film that have been borrowed from Verne’s perhaps best known novel (and several others), the film itself is, as most sources also correctly state, a rather faithful adaptation of one of Verne’s lesser known works, Face au Drapeau (1896), published in English as Facing the Flag. In case there is any doubt, the Czech title of Face au Drapeau is Vynález zkázy, which is also the original title of Zeman’s movie. The English translation of this title is roughly “Invention for Destruction”, or put slightly more title-friendly wording, “The Invention of Doom”. The movie was originally released in the US as The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, but has since been released on home media under its literal title, Invention for Destruction.

Facing the Flag is, as stated, one of Verne’s lesser known works. It was written toward the end of his career, when he was struggling to come to terms with his brother’s mental illness and his own increasing frailty (partly due to getting shot by his nephew Gaston). Many of his latter books also paint a bleak picture of the future: science and technology now seldom hold the promise of a brighter future, but rather the seeds of our destruction. While his central characters had sometimes been morally ambiguous, now they were often filled with bitterness and rage.

Facing the Flag is a bleak novel, and Karel Zeman’s main departure from it is that he has turned it into a whimsical fantasy adventure. Still the film follows the plot of the book quite closely. The most notable change is that Zeman has scrambled the main characters. In the book, Professor Roche is not a kind-hearted inventor that is being used by a cruel villain. In the book, Roche is the French inventor of a new, terrible explosive that he hopes to sell to the highest bidder. However, no country wants to buy his unproven theory, and he goes crazy with bitterness and is institutionalised. At the asylum, he and his nurse Simon Hart are kidnapped by the pirate Count d’Artigas, who brings Roche to his island lair. Here, Roche becomes d’Artigas’ willing accomplice in his plans for world domination.

The novel also contains a submarine, which d’Artigas uses to ram merchant and military vessels, just like in the movie. Like in the film, Hart is able to contact the outside world through the use of a balloon, and like in the film, the book ends with a confrontation between Roche and his new weapon, and the united fleets of the world (including a submarine battle). However, the book ends on a rather silly note, which reveals Verne’s deep-set nationalism, as well as the atmosphere of the times: France’s pride and sense of security were shaken by the so-called Dreyfus affair. When Roche hears the bugle call from the French navy, he is snapped out of his madness, and refuses to fire on the fleet of his home country. Engaging in a struggle with the pirates, he ultimately blows up himself and the whole island.

Zeman, on the other hand, turns Roch into an absent-minded professor, duped by Artigas. And while in the book, “Count d’Artigas” was the alter ego of pirate captain Ker Karraje, Zeman has split the two identities into two characters, so the count is the main villain, and the pirate captain is his lackey. In the end, Roch does not so much have a change of heart, as he realises that he has been duped. Like in the book, Roch uses his invention to blow up himself and the island.

Another major change, although not really, is Zeman’s addition of Jana. While the claim that Verne never included women in his novels is an unfair exaggeration (women play integral roles in several of his novels), it is true that he often dispensed with women altogether if a female character was not required to tell the story he had in mind, or to add flavour as an “exotic beauty”. Facing the Flag had no need for a female character, and thus Verne didn’t add one. I say that Zeman’s addition of Jana is not really a major departure from the book, as Jana has no real story purpose in the film, either, other than giving Hart a love interest and adding a pretty woman to the film’s ad campaign.

So, all in all, Invention for Destruction is a fairly accurate retelling of Facing the Flag, although Zeman has included nods to several other works by Verne. There’s a submarine scene with lines from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, as well as an underwater treasure hunt. There’s a cameo by Robur the Conquerer’s airship “Albatross”, and the pirates’ volcanic lair resembles that of Robur’s in Master of the World. There are also small winks to, at least, Five Weeks in a Balloon, The Mysterious Island and Around the World in 80 Days. Artigas’ giant cannon is borrowed from The Begum’s Millions.

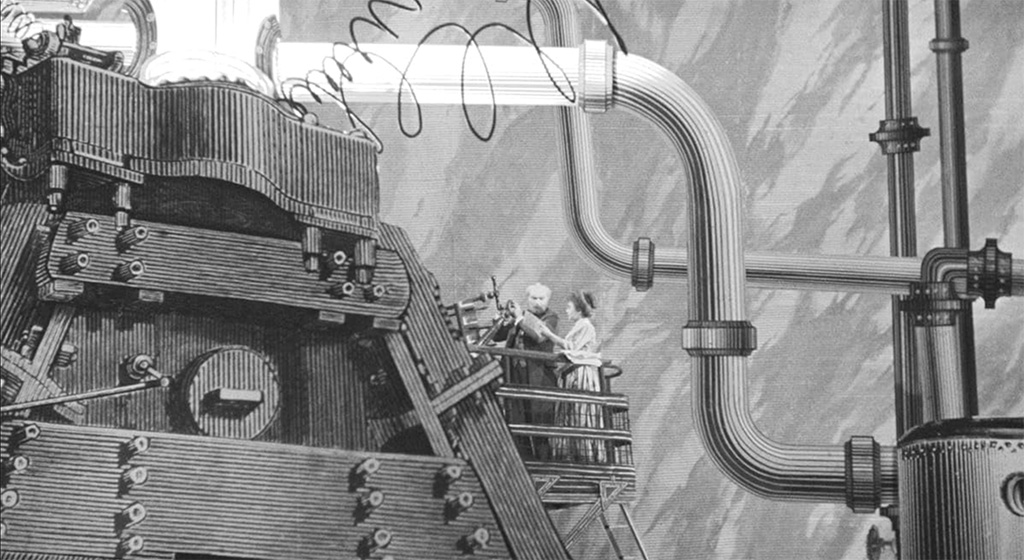

As stated, what most viewers take away from the movie is its unique visual style. Much of the imagery of Verne’s novels come from the illustrations of the original books, often done as wood engravings by artists such as Edouard Riou, Alphonse de Neuville and Leon Bennett, and the feeling of these illustrations became ubiquitous to the faboulous world of Jules Verne. From the beginning, Zeman was determined to make the film in the style of these illustrations. According to Andrew Osmond’s book 100 Animated Feature Films, Zeman said: “The magic of Verne’s novels lies in what we would call the world of the romantically fantastic adventure spirit; a world directly associated with the totally specific which the original illustrators knew how to evoke in the mind of the reader … I came to the conclusion that my Verne film must come not only from the spirit of the literary work, but also from the characteristic style of the original illustrations and must maintain at least the impression of engravings.”

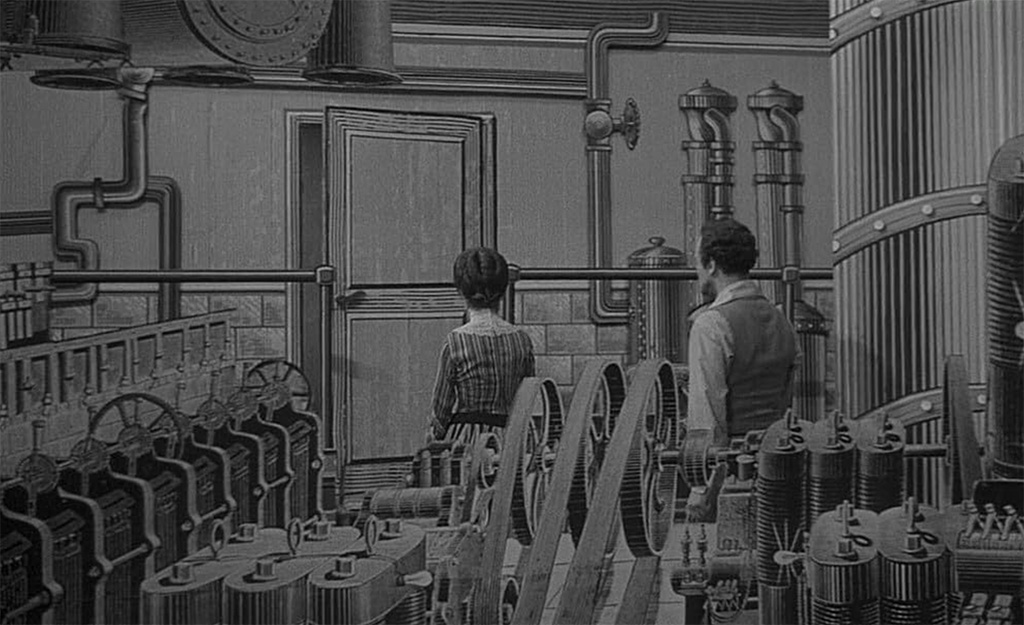

This style, in stark black-and-white, is prevalent in every element of the film, from backgrounds and sets to props, costumes, and even the acting. It is a surreal world, where the line between fairy-tale and reality blurs, with live actors interacting with what is essentially a cartoon world, but a cartoon world which was originally designed to look as realistic as possible. In a way, this is very much contradictory to the spirit of Verne, who, I am sure, would have been adamant that adaptations of his movies be made to appear realistic. Despite all his fantastic inventions, realism was always a guiding light for the author. Nevertheless, the style does evoke the romanticism and escapism of Verne’s work, transporting the viewer into Verne’s Victorian age. In 1955, Karel Zeman directed another film, Journey to the Beginning of Time (review), inspired by, rather than based on, Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth. In that film, Zeman used all the tricks in his book to make dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures and environments come to life in as much photorealism as possible. Here, he does the exact opposite, bringing Jules Verne’s story from realism back onto the pages of a story book.

To achieve his effects, Zeman and his trick photographer Antonín Horák pull out all the stops, using a myriad techniques — from glass mattes and backdrops to travelling mattes, split-screen, rear projection, cel animation, cutout animation and puppet stop-motion animation, live-action puppetry, set design, costume design, practical effects and even acting choices.

One the most talked-about style choices is Zeman’s decision to riddle the picture with thin, parallel lines, reminicent of the hatching on old wood engravings. The lines in these old illustrations were a practical solution to a problem: since illustrations made from engravings were binary black-and-white, and didn’t allow for shading, the artists added lines to suggest shadows, gradients, differences in colour and lighting. What could be seen as a flaw ultimately became a defining trait of engravings and linotypes. Zeman ran with the aesthetic, but according to Horák, these hatching lines also served a practical purpose. The Czechoslovakian filmmakers didn’t have access to Hollywood hardware, and had to make do with equipment that wasn’t quite suitable for the ambitious effects that the film team were trying to achieve. Most of the effects had to be done in camera, meaning that the same strip of film was run through the camera often three or four times for the different layerings of effects. However, the camera didn’t quite keep the film rock steady, which meant that there was the slightest wobble that was discernable at the edges of the different composites. But according to Horák, the hatching lines disquised this wobble. In a way, this brings the effect into a neat full circle, as the creators, like their predecessors, were turning a practical solution to a problem into a style feature.

The aesthetic is so seamless that it is often impossible to work out where a backdrop ends and a set piece takes over, what’s an actor and what’s an animation. In some cases three-dimensional objects are represented by two-dimensional, painted sets, but sometimes, bewilderingly, the opposite is true. In one scene, a staircase is painted to look as if it was a two-dimensional, flat drawing — until the actors start to walk on it, and you realise that it is a real staircase and not a flat backdrop.

What also makes the film interesting is that Zeman’s hasn’t updated anything, despite time having long since passed the outlandish 19th century visions of what the future would look like in the year 2000 and beyond. When Verne published many of his most famous novels, the internal combustion engine had not yet been invented, nor had the airplane. And Zeman sticks to it. In fact, Zeman not only sticks to Verne’s designs, but has also clearly studied other turn-of-the-century visions of the future, as imagined by artists like Albert Robida, William Heath and Jean-Marc Côté. There are whimsical, fantastical contraptions on display that are as if ripped straight from Côté’s famous 1899 postcard collection depicting life in the year 2000. There are underwater bicycles, a submarine propelling itself with flippers, a bird-like flying machine and even a foot-pedalled airship as if taken straight from Edwin S. Porter’s 1902 short film Happy Hooligan and His Airship (review).

Zeman’s quest to imitate the illustrations went as far as the acting. Zeman instructed the actors to act deliberately and restrained, avoiding any superfluous movements, like scratching their heads or fiddling with their hands — things that the characters in the illustrations were never seen doing. This gives rise to very clinical performances from all the actors, as if disengaged or even uninterested.

The seemingly stiff acting and the whimsical and episodic plot has tended for a lot of commentators to latch on the film’s visuals, rather than its content. The late Bill Warren in his book Keep Watching the Skies! bemoans many critics’ failure to “understand [that] the film is more than just the old drawings brought however inventively to life. It is at once an affectionate spoof of Verne and the 19th-centure attitutes toward science, a tribute to Verne and these attitudes, and a reinterpretation of them in pacifist termes.” Warren continues to say that “Zeman embraces Verne for his virtues, while being aware that, while predictive, the author’s works are dated and charming, almost quaint.”

I am inclined to agree with Warren — to a point. Zeman was steeped in Verne, and knew the author inside and out. But Zeman was also a child of both WWII and the cold war, and had witnessed in his lifetime the march of technology, such as Verne could only dream of. But as opposed to what Warren seems to think, Verne DID dream of this future — he had nightmares about it, as illustrated by dark novels such as The Begum’s Millions, Facing the Flag and Master of the World. Many of Verne’s stories touched on serious political and social issues, such as colonisation, imperialism, racism, industrialism and even, to some extent, class. Some even have a dystopian element to them. Zeman’s choice of adaptation, Facing the Flag, seems like a somewhat odd choice for a vehicle that sets out to spoof (or indeed celebrate) the childish techno-optimism and romanticism of Verne, as it is one of his bleakest novels. Indeed, Zeman has to totally invert the tone of the book in order to achieve his goal.

Nay, I don’t think this is so much about reimagining Verne in pacifist terms — those themes were there already in Facing the Flag, so there’s no need to reinvent them. Instead, Zeman makes the story much more “charming, almost quaint”, as Warren puts it, than it actually is, by turning Roch into a classic absent-minded professor and the villain into a rather harmless film serial villain. More than a sly spoofing of Verne’s naive ideas, the film feels like a child’s recollections of Verne. Here are all the wonders a child would take with them from the Jules Verne novels, but rather little of the philosophical, political and social commentary that runs through even his most naive adventure novels.

Zeman also adds some fun and whimsical moments of his own, such as a scene in which Jana dries her clothes on a cannon, and casually lights a fire next to a powder keg, sending the pirate captain into a fit, or a rather pointless but romantic underwater swordfight between two pirates over sunken treasure. The best single part of the movie is probably a scene in which Artigas is shown news reels by his pirate projectionist, getting news about wars and troop movements in the world, all done with cut-out animation in a fantastically whimsical style, much of it reminiscent of Terry Gilliam’s work. In fact, one clip, of soldiers riding camels on roller skates(!), could be ripped straight from a Monty Python skit. One fun bit of scripting is where Hart escapes and climbs up Jana’s window, only to find her in bed. Despite his urgent business, Victorian moral code dictates that he climb back out and dangles from his fingertips at the windowsill so that Jana can get dressed before he re-enters. (As Bill Warren rightly points out: this is not only Zeman making fun of the Victorian moral code, it’s the kind of joke that Victorians themselves would have found funny.) It’s these moments, along with the imaginative and fun design that makes Invention for Destruction such a delight to watch.

Adding to the otherworldly atmosphere is Zdeněk Liška’s eerily mechanical, string-heavy score. It’s not what you’d expect from a Jules Verne adventure, and in a way complements the restrained acting. Many consider it longtime Zeman collaborator Liška’s best work.

One over-analyses the movie at one’s own peril. There’s little food for thought here that is not already in Verne, and Zeman doesn’t even scratch the surface in regards to Verne’s socio-political themes, but rather dumbs them down. The plot holds together nicely, though punctuated by some animated sequences that are very reminiscent of the Méliès-style filmmaking, with long takes and few edits, that may be taxing and slow for a modern audience. Because of the techniques used, the cinematography is also very static, again recalling Méliès’ staged movies. I don’t think you need to over-intellectualize this film in order to enjoy it for what it is: a childlike adventure into the world of Jules Verne, as reimagined by a WWII survivor in the 50s.

The plot of the film is ultimately inconsequential, as Zeman doesn’t lend it any particular gravitas or pathos, and has it unfold in an episodical manner, jumping from one set-piece to the next, inhabited by inhibited actors playing the idea of characters rather than actual characters. The movie takes on Jules Verne at a meta level, bringing us the feeling and atmosphere of a Jules Verne novel without bothering too much with the content or the ideas. It is a film that I would like to like better than I do, because of the passion put into it, the truly marvellous visuals and the fun, whimsical tone that just makes it impossible not to become infatuated. But the acting leaves me cold, the characters are devoid of character, and the story is a potpourri of iconic moments and images from Verne, that would have either needed a stronger contemporary commentary or more emotional pathos. What the film does remind me of, more than anything, is The Extraordinary Adventures of Saturnino Farandola (review), an epic 1913 silent adventure, based on a comical adventure novel written by the afore-mentioned Alfred Robida, which was a loving pastiche on Jules Verne. Yes, pastiche is perhaps the right word to describe Invention for Destruction, rather than satire.

Nevertheless, this is one of the best cinematic Verne adaptations out there, staying true to the author’s vision and word as few other adaptations have ever done (Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea [1955, review] is another rare exception). It is artistically mind-blowing and it is a fun, breezy watch for anyone wanting to be sucked into an Extraordinary Voyage. In terms of inventiveness, visuals and uniqueness, it is a true masterpiece. I, for one, find myself missing some of the colourful burlesquery in regards to the characters that Verne was often so capable of. I don’t invest in the film’s people, and thus don’t invest in the story. The movie moves me more on an intellectual level than an emotional one – however startling, fun and enjoyable it may be.

Reception & Legacy

Vynález zkázy was released in Czechoslovakia in August, 1958, and went on a victorious tour throughout Europe. According to French film scholar Jean-Loup Bourget, the movie was praised in such influential magazines as Cahiers du Cinema and Positif, and director Alain Resnais thought it was among the top 10 films of 1958. It won numerous European movie awards, including the Grand Prix at the Brussels International Film Festival, the Silver Sombrero at the Guadalajara Film Festival and a Crystal Star from the French Academy of Film.

The movie, retitled The Fabulous World of Jules Verne, was released in the US in June, 1961, by Warner – a rare occasion when a major studio gave an Eastern European film – part animation at that – a major release. Warner’s decision was probably informed by the film’s success in Europe, but also by the fact that there was a Jules Verne boom in Hollywood, which was kickstarted in 1955 by Disney’s20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and was further fuelled by United Artists’ star-studded epic Around the World in 80 Days (1956). In 1958, Warner released their own Verne pic, From the Earth to the Moon (review), directed by Byron Haskin. The Fabulous World of Jules Verne was dubbed to English and released with a new introductory segment by TV star Hugh Downs. Most of the names of the cast and crew were anglisized, so thatLubor Tokoš, Arnošt Navrátil, and Miloslav Holub were credited as “Louis Tock”, “Ernest Navara”, and “Milo Holl”, respectively. The movie was marketed as a children’s film, and released on a double bill with the German melodrama Bimbo the Great, which also wasn’t really a kiddie film, despite being set at a circus. In order to drum up interest for the visuals, Warner created a costly PR campaign touting the “new” technique of “Mystimation”, with which the movie was supposedly made.

US critics were thrilled. The New York Times critic Howard Thompson found it “fresh, funny and highly imaginative,” with “a marvelous eyeful of trick effects”. Pauline Kael called the film a “wonderful giddy science fantasy”. Kael spent most of her review on the visuals of the movie: “The variety of tricks and superimpositions seems infinite; as soon as you have one effect figured out another image comes on to baffle you. […] The film creates the atmosphere of the Jules Verne books which is associated in readers’ minds with the steel [sic] engravings by Bennet and Riou; it’s designed to look like this world-that-never-was come to life, and Zeman retains the antique, make-believe quality by the witty use of faint horizontal lines over some of the images. He sustains the Victorian tone, with its delight in the magic of science, that makes Verne seem so playfully archaic.”

Several outlets commented on the film’s misleading marketing as a kiddie movie. LIFE magazine wrote: “There is a great danger that adults may assume that this is a child’s movie and will leave it to the children. If so it will be a pity for the adults will be deluding themselves out of some delightful movie watching”. Variety noted that The Fabulous World of Jules Verne was paired with Bimbo the Great, and critic Tube wrote: “but actually it deserves a more respectable exhibitory fate”. Harrison’s Reports even went as far as suggesting that children might not even like the movie very much, as the style of the film “produces a slow-moving artsy effect that will displease the unsophisticated action fan, attracted by a razzle-dazzle promotion campaign”.

Trade magazines were also generally positive. Variety did comment on the “crude dramatic nature of the proceedings”, but opined that the visuals more than made up for what was lacking in the script department: “it is the sets, the animation and the artwork in general that give this picture its peculiar individuality, its unique character. One experiences the sense of witnessing the illustrations that accompany Verne’s books come to life.” The Film Bulletin gave it a 3/4 business rating promising “it is certain to appeal to audiences of all ages”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor called it “interesting and different”, and noted that the “Mystimation technique is quite effective”, although, like Variety, the magazine also pointed to weaknesses in scripting and pace.

There is an idea regurgitated in several books and online sources that The Fabulous World of Jules Verne was a commercial flop in the US. This idea seems to have originated with Bill Warren, who in his passionate defense of the movie scalds the film’s critics and the (supposed) American aversion to art cinema in general. He writes that the film “couldn’t have been very profitable in America”, but backs this claim only with anecdotal evidence (despite this, even Wikipedia refers to Warren’s book as proof that the film was a financial flop). On the contrary, the Karel Zeman Museum in Prague claims that Invention of Destruction is the most commercially successful Czech feature film to date: upon its original release it was sold to 72 countries, and on its opening weekend in the US, it played in 92 theatres simultaneously in New York alone. Wheeler Winston Dixon at Senses of Cinema reiterates a statement I have seen in several writings on the film: “Like so many others in the United States, I was first exposed to Karel Zeman’s exotic adventure film Vynález zkázy (Invention of Destruction, 1958), when it was released in the West”. Clearly, a lot of Americans saw the movie.

As of writing, the movie has a 7.5/10 rating on IMDb based on nearly 3000 votes, and a 3.9/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on over 5000 votes. Rotten Tomatoes gives it a 100% Fresh rating and a weighed 8.5/10 avegare critic rating. In other words, it is a movie that is highly regarded by both audiences and critics.

Most critics today tend to gush over the visuals, but lament the flat acting. Todd Stadtman at Die, Danger, Die, Die, Kill! writes: “The performances in Vynalez Zkasy […] are generally competent but flat, which leaves the performers constantly at risk of being upstaged by all the visual sorcery that surrounds them. […] If, in this case, that aesthetic becomes a bit claustrophobic in practice, that is to be begrudgingly forgiven. Suffering their occasional indulgences is the price we pay for having artists of such unique vision in the world.” Lee Robert Adams at Czech Film Review says: “Amid this riot of imagination are the actors, who are the dullest thing about the movie. It’s not really their fault – the performances are fine enough and they were instructed to act in a decorous manner to match the setting – but they don’t have a chance of upstaging the production design. […] Despite the short running time, the pace of Invention for Destruction occasionally flags. Yet every time it does some new wonderment arrives to astonish and delight.”

Nevertheless, the almost unanimous opinion is that Invention of Destruction is nothing short of a masterpiece. Wheeler Winston Dixon at Senses of Cinema writes: “[P]erhaps in Vynález zkázy […] Zeman created his finest and most accessible film, now in the pantheon of the greatest hybrid animation/live action films ever made. Vynález zkázy is an imaginative delight, and a stunning personal achievement. Once seen, never forgotten.” Richard Scheib at Moria gives the movie 4.5/5 stars, calling it “a film that almost approaches pure art in its very uniqueness”. Then there is the film’s staunchest ally, Bill Warren, who in his Magnum Opus reviewed every science fiction movie from 1950 to 1962 that has had a theatrical release in the US. In his original 1982 edition of his book, he called Invention of Destruction “the best film covered in this book”, as well as “the best movie ever adapted from a work by Verne“. In a later edition, he backtracked somewhat, admitting that he exaggerated a bit in order to make people take note of the movie, but still argued that it was among the top 5 movies he covered.

It is difficult to say to what extent Invention of Destruction influenced the aesthetic of steampunk, if it did so at all. However, Howard Waldrop and Lawrence Person in their review in Locus magazine called it “the ultimate steampunk movie”. The film was a huge influence on animator and director Terry Gilliam, who cites Karel Zeman as one of his biggest heroes.

Cast & Crew

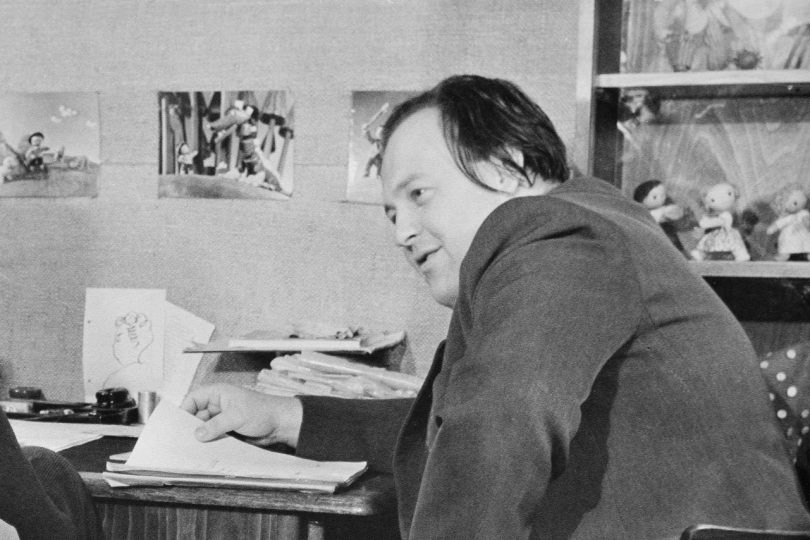

Karel Zeman was born in 1910 in a town that was then in Austria-Hungary, now in the Czech Republic. At a young age he focused his creative talents on advertising, and studied advertising in Marseille, where he also worked for a while, before returning to his home country. On the way home, he spent time in Egypt, Yugoslavia and Greece, from an early age adopting an internationalist mindset. During WWII Zeman worked as the head of advertising at a department store in Brno, where his artistic talent was noticed by movie director Elmar Klos, who offered him a job at the small Zlin animation studio.

After working as an assistant to Hermína Týrlová, Zeman directed his first short film in 1945, and from the beginning started experimenting with new ideas, such as combining live-action footage with animation. During the 40s he developed a popular series of animated short following a “Mr. Prokouk”, and made a groundbreaking animation short using glass figurines. He made his first feature film in 1952, based on Persian fairy tales, and again used a variety of techniques, combining live-action with animation.

However, Zeman’s golden age was between 1955 and 1970, during which time he directed six feature films, and during which time he became closely associated with the works of Jules Verne. Four of the films were based on, or inspired by, Verne. Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955) was vaguely inspired by Journey to the Centre of the Earth, and followed four boys travelling backwards in time using a row boat, until they come to the very moment that life was first created in the oceans. The film relied heavily on practical puppetry, but also contained animation of all different sorts. His next two films are perhaps his best regarded: Invention of Destruction (1958) and The Fabulous Baron Munchausen / Baron Prásil (1962). Both were highly visually inventive and took their style from the wood engravings of the 19th century. Other Verne-inspired movies were The Stolen Airship (1967) and On the Comet (1970).

In the 70s, Zeman returned more traditional animation, and directed a number of short films and a handful of animated feature films, best known of which is probably The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1978). During his career, Zeman won numerous awards and acclaim for his films, and is cited as an inspiration by directors such as Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton and Wes Anderson. The Karl Zeman Museum in Prague opened in 2012.

Zdeněk Liška is considered one of the greats of Czech film composing, pioneering the use of electronic and electroacoustic music in movies. He is particularly remembered for his work with animators Jan Svankmajer and Karel Zeman. He composed quite a few science fiction movies, including Invention of Destruction (1958), The Man from Outer Space (1962), Ulysses and the Stars (1966) and Talíre nad Velkým Malíkovem (1977).

Most of the actors were well-known in Czechoslovakia, but will probably not be familiar to an international audience. Lead actor Lubor Tokos appeared in over 80 film or TV productions and was very active on stage. Apart from his lead in Invention for Destruction, he might be best known internationally for his supporting role i Otakar Vavra’s 1970 movie Witchhammer. Most Czechs remember him from his grandfatherly roles of his later career. He also appeared in the brain transplant movie Dvojrole (1999).

Miloslav (often billed as Miroslav) Holub, here as Artigas, was a prominent actor, writer and director on the Czech stage, but also appeared in numerous films, not seldom as villains. He is best known for appearing in five of Karel Zeman’s movies, including all four Jules Verne adaptations. He was also the first actor to ever appear in Czechoslovakian TV, reading a poem in the country’s very first brodcast.

Otto Šimánek, also a prominent stage actor, specialised in pantomime, and also taught the artform. He remains best known for using his mime abilities as the titular silent wizard in the children’s TV show Pan Tau (1966-1977), which was a huge hit and was seen by children in several European countries – the show was especially popular in Germany.

EDIT 9.9.2024: Verne was shot by his nephew Gaston and not by his brother, as the original text suggested.

Janne Wass

Invention for Destruction. 1958, Czechoslovakia. Directected by Karel Zeman. Written by Karel Zeman, Frantisek Hrubin, Milan Vacha. Based on the novel Facing the Flag by Jules Verne. Starring: Lubor Tokos, Arnost Navrátil, Miroslav Holub, Frantisek Slégr, Václav Kyzlink, Jana Zatloukalová. Music: Zdenek Liska. Cinematography: Antonín Horák. Editing: Zdenek Stehlik. Production design: Karel Zeman. Costume design: Karel Postrehovsky. Special effects: Karel Zeman. Produced by Zdenek Novák for Ceskoslovenský Státní Film & Filmové Studio Gottwaldov.

Leave a comment