Another prehistoric reptile threatens Tokyo, and the Japanese military throws everything in its arsenal at it. That’s pretty much the plot of Toho’s ill-fated 1958 movie Varan, a TV project that was hastily punched up to feature film status when the American buyer pulled out in the middle of filming. 2/10

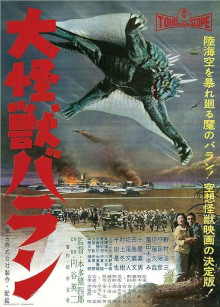

Daikaiju Baran. 1958, Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Sinichi Sekizawa, Ken Kuronuma. Starring: Kozo Nomura, Ayumi Sonoda, Koreya Senda, Akihiko Hirata, Yoshio Tsuchiya. Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka.

When two biology students are killed under mysterious circumstances in a remote mountainous area of Japan, one of the students’ sister, Yuriko (Ayumi Sonoda), a journalist, sets out to find out what happened to them. Along she takes her photographer Horiguchi (Fumindo Matsuo), and her brother’s friend Kenji (Kozo Nomura). Arriving at a remote, pimitive village, they are warned about the god Baradagi, who the villagers claim have killed the two students. Not heeding the warnings, the three proceed to a lake, where they encounter a giant prehistoric reptile. Horiguchi is astonished – he identifies it as the extinct dinosaur Baranopode, or Baran.

Toho’s Daikaiju Baran or Varan (1958) is sometimes referred to as Varan the Unbelievable in English, even though that is the title of the 1962 US version, which uses only 15 minutes of the Japanese movie. Originally developed as a joint US-Japanese TV production, but bumped up to a theatrical release after the American partner pulled out, Varan is one of the least revered of Toho’s kaiju films, even though it is directed by Ishiro Honda and has effects by Eiji Tsuburaya.

In the usual form of Japanese kaiju movies, we now proceed with meetings, briefings and exposition, where scientists and military types discuss the threat and decide to send a military force to destroy Baran. Key players are biology professor Dr. Sugimoto (Koreya Senda) Military officer Katsumoto (Yoshio Tsuchiya) and bomb expert Dr. Fujimori (Akihiko Hirata).

By this time in the proceedings, Yuriko, Horiguchi and their comic sidekick photographer are more or less pushed out of the story, and the plot focuses on the miltary’s attempts to bomb Baran into oblivion. First an operation is launched at the monster’s lake, but, as is usually the case in these films, nothing the military can throw at Baran has any effect. Instead, Baran takes flight and relocates to the ocean, heading towards Tokyo. Now the navy tries to kill it with depths bombs, and then with armour-piercing rockets, but both times without success. Dr. Fujimori then suggests they might try a new kind of explosive used in mining, that is 20 times more powerful than dynamite. However, Fujimori himself is doubtful, as the explosives work by blowing up rock from the inside, and he suspects that trying to blow Baran up with them from the outside will not work. However, with no better options, the task force decides to drive a truck filled with the new explosives up to Baran as he lands at Tokyo bay. The bombs harm Baran, but only enough to make him angry, and he starts trashing buildings at the dock. It seems Dr. Fujimori was right: they must somehow get Baran to eat the explosives. But how?

Background & Analysis

After the success of the American release in 1957 of Toho’s colour movie Rodan (1956, review), TV company AB-PT (later ABC) approached Toho with a desire to jointly produce a TV movie for the US market. The film, dubbed Varan the Unbelievable in English, was supposed to be a three-part film with 30 minutes for each segment. The end result – for reasons we’ll get into below – was a Japan-only feature film release with the title 東洋の怪物 大怪獣バラン or Daikaiju Baran (“Giant Monster Baran”). Today it is usually referred to in English as simply Varan.

Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka went to work with the intention of making a low-budget version of a Japanese kaiju movie – with expenses kept at a minimum in order for Toho to make a profit from the sale to AB-PT. Ken Kuronuma and Sinichi Sezikawa were tasked with writing the screenplay, with the instructions to keep it “basic and simple”, enough to satisfy the American demand for more kaiju. Ishiro Honda, who had directed both Gojira (1954, review) and Rodan, was attached to the project, as was Toho’s special effects guru Eiji Tsuburaya and composer Akira Ifukube, whose memorable music for Gojira did so much for the film’s success. Because it was to be shown on TV, the picture was to be made in black-and-white, even though Toho had already transitioned to colour for their kaiju films. It was filmed in the 1:33:1 format for TV presentation.

Ishiro Honda has said in an interview that he apdated his direction with the intent that the film would look powerful on the small screen, which meant less wide shots and lesser details than would have been required for a film with a theatrical release. Shots were framed tightly in order for actors to be clearly seen, and for the monster to jump out of the TV screen. This philosophy also informed the work of Eiji Tsuburaya, who could get away with special effects of lesser quality, as they did not need to stand up to scrutiny on the big screen. The film contains some of Tsuburaya’s crudest miniature work. Even when watched on a small screen, you can see strings pulling the minature tanks, that clearly have figurines of soldiers inserted into them. The final stomping of Tokyo in the end is remarkably small-scale compared to previous kaiju movies, and consists merely of Varan stomping down the block of a naval yard. Several miniature scenes involving the air force and explosions are borrowed from Gojira and Godzilla Raids Again (1955, review).

Filming began in July in 1958, but in the middle of the shoot, AB-PT withdrew from the project. Some sources give as the reason for the company’s retreat that AB-PT folded in the summer of 1957, but this is not the case: ABC’s television arm was doing well in 1957, and picking up steam as AB-PT was forced to sell large shares of its movie theatres due to new anti-trust regulations. But neither have I been able to find any other reason for AB-PT’s exit from the Varan project.

Whatever the case, AB-PT’s decision sent the project into disarray. Shooting was nearing an end, and Toho had sunk a significant amount of money into the production. A decision was made to instead remake the movie for a theatrical release in Japan – a decision that Ishiro Honda fumed over. In the 2017 biography Ishiro Honda, a Life In Film, he says: ” Of course it did not work. We had a very hard time adjusting it. The desk-side planners just did not understand how the filming side worked.”

For one thing, the film was shot in black and white and in a full-screen aspect ratio for TV, while Toho’s films were shot in widescreen and colour. Also, it was shot in as three different segments, which didn’t work as a continuous feature film. On top of this, it was made on the cheap with the intension of being shown on a small TV screen and not in a movie theatre. First of all the script had to be restructred. Sin’ichi Sezikawa added a new subplot involving the students in the beginning of the film looking for a rare butterfly in the area where Varan lives. You’d expect the sudden appearance of a butterfly alien to Japan to have some bearing on the rest of the plot, but it doesn’t, making the whole butterfly business an oddly irrelevant thing to open the movie with. It was also decided to prolong the military’s battle against Varan by adding yet another attempt at killing the creature. Here Honda scoured navy stock footage and added the segment where the navy tries to blow Varan out of the water with depth charges. It is also possible that the sequence with armour piercing bombs is an addition for the movie version, as it features a lot of special effects borrowed from previous Godzilla films and wide shots of Varan in the ocean that seem out of place with a lot of the rest of the tightly shot TV footage.

As a kaiju, Varan is not a particularly creative monster. It looks a bit like a cross between Godzilla and Anguirus, and walks alteratively on four or two legs. Its snout is immobile and has a weird, slightly comical frown that for some reason reminds me of the monster from AIP’s cheapo The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues (1955, review). I do like however, the fact that it seems lighter and more flexible than Toho’s previous kaiju suits, giving suit actors Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka greater mobility, which in turn gives Varan more versatility of motion and performance. Varan was reportedly supposed to look like a cross between Godzilla and a mythological Japanese turtle-like being called a kappa.

Varan’s suit seems to be made out of foam latex, but it might also be rubber, I’m not enough of an expert to tell the difference. The spikes on the monster’s back were fashioned out of transparent rubber hosing, and the scales from flattened peanut shells. Apart from the suit, a one full-size puppet was made for the scene where Varan is flying, and a smaller hand puppet was used in several miniature scenes.

Typically for Japanese science fiction movies, characterisations are almost non-existent. As usual, ten or so characters compete for screen time, and the nominal leads are pushed out of the story about halfway through, when everything becomes a bomb fest. Again, as in films like The Mysterians, all actions are performed by committee and much of the film’s dialogue takes place in conference rooms. Partly this has to do with the Japanese culture of putting the collective before the indivicual. But ensemble casts don’t need to be faceless and devoid of personality. This is a scripting issue, one that keeps repeating itself in these films. Assessing performances in Varan is moot, as the actors don’t really get to attempt any performances. They are just in place to deliver their lines and move what little plot exists forward.

The main problem with Varan is that it feels like two thirds of the film simply consists of the military shooting things at Varan. In that sense it is reminiscent of The Mysterians (1957, review), but at least that film had good effects to like like, and Toho gained the full cooperation of the Japanese military. Here Honda and Tsuburaya make do with sub-par effects, loans from other films and stock footage. Plus, there is no subtext, no metaphorical value in any of the proceedings. It’s just a giant monster heading towards Tokyo that gets bombarded. The movie is full of decent actors and kaiju movie legends like Akihiko Hirata and Youshio Tsuchiya, but none of them get anything to do. All this results in a very boring picture.

Taking into consideration the troubled production of the movie, it is astounding that Toho was able to string together such a coherent and functioning feature film at all. But the quality here is beneath Toho even on a bad day. Varan is not unwatchable in any way, and I am told the US version starring Myron Healy from 1962 is considerably worse. But considering the wealth of kaiju movies to choose from, I cannot see any reason to recommend this film to anyone.

The best thing about the film is Akira Ifukube’s orchestral score, which is a lot better, more dramatic, than this film deserves. If some of the soundtrack sounds familiar, it is because it reused as Rodan’s theme in subsequent Toho movies, and another part of the score was used for Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster (1964).

Reception & Legacy

Daikaiju Baran premiered in Japan on October, 1958, and no attempts were made to give it a foreign release, as the film was simply a way for Toho to recuperate its losses from the botched American TV deal.

As usual with these older Japanese movies, I have found few contemporary Japanese reviews, and in this case no no other contemporary reviews, either, as the film wasn’t shown outside Japan until it started to make its rounds on video. Toho was also iffy about giving it a wider release in Japan, because the depiction of the villagers could be seen as a slight to the Burukumi minority of Japan. Why Honda chose to allude to the Burukumi as backwards and superstitious peasants once again, despite the criticism for his doing so in the snowman movie Ju jin yuki otoko (1955, review) is something we can only speculate about. However, the book Ishiro Honda, a Life in Films cites one review from Tokyo Weekly, which states: “Varan attacks Haneda Airport, but it reminds me of the conclusion of any other old Godzilla. There’s nothing new. It’s really about all they can do with a monster movie.”

In his book Keep Watching the Skies! Bill Warren writes: “Even the Japanese version of the film is perfunctory and poorly organized.” Warren isn’t as hard on the special effects as many other critics, simply noting that they are quite small-scale.

As of writing, Varan holds somewhat surprisingly high audience scores on both IMDb (5.2/10) and Letterboxd (2.6/5), considering most critics view the picture as sub-par.

Most of my go-to critics have only seen the US version of this film. However, Jon Davidson at Midnite Reviews gives the film a very generous 5/10 star rating, considering his verbal verdict: “Daikaiju Baran forgoes narrative substance in favor of copious action, thereby solidifying its reputation as the weakest entry among Toho’s original lineup of kaiju films. Especially disappointing is the absence of social commentary, which, until this point, had been a defining aspect of the Japanese monster movie.”

Robert Hood at Hood Reviews says: “I must confess that the only part of the film that really engaged me was the first third, where there still existed the possibility of something imaginative happening. The mountain setting, the isolated lake, the superstitious natives and the hints of mysticism that gather around their concept of the Monster God Baradagi all have potential. I loved the use of wind and fog as it heralds Varan’s rise. Unfortunately the script never connects any of the dots, gives no interesting rationale for the monster’s appearance (“he’s angry because you came too close to his lake” seems a bit desperate), and pushes its only developed characters into the background after the first act in order to pursue the usual military light-and-hardware show for the remainder of the film’s running time. All the good destruction and monster rampage is here, of course, but it becomes a bit meaningless after a while. I confess I wanted some scripting to be in evidence.”

Varan was supposed to have a major appearance in Destroy All Monsters (1968), but upon inspection the suit had deteriorated beyond repair in storage, so Varan only made a couple of short cameos using puppets that had been made for the first films. when Sinichi Sezikawa wrote the script for what ultimately became Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972), he had included Varan in a major role, but was ultimately dropped from the story. Similarly, director Shusuke Kaneko planned the third movie of Godzilla’s Millennium era to feature Godzilla, Varan and Anguirus, but was told by the studio that the latter were among the least popular kaiju among the fans, and asked to replace them with better-known monsters. As a result, Varan was again sidestepped in what became the film Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001).

However, both the music from Daikaju Baran and Varan’s roar continue to live on. In fact, according to Wikizilla, Varan’s roar was made up of different recordings of both Godzilla and Rodan, edited together and played at different speeds. Rodan’s roar was already a modification of Godzilla’s roar, which was famously created by Akira Ifukube by having one of his assistants dragging his hand across an unwound contrabass E string with a clove covered in pine tar. The Varan version of the roar would end up being used by several other monsters in subsequent films.

Cast & Crew

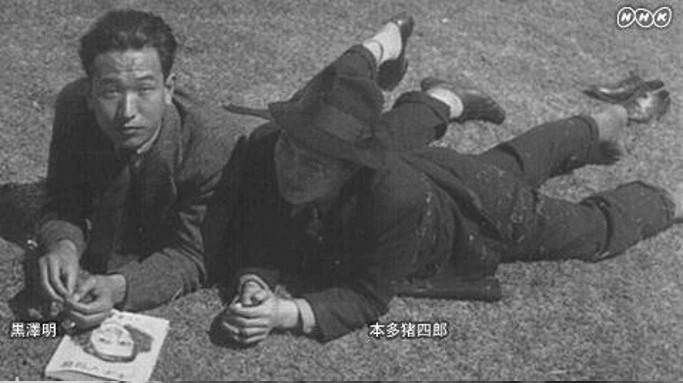

I have written about Ishiro Honda before on this blog, see for example my write-up for my review of Gojira for more detailed information on him. Honda, an up-and-coming director and former assistant to Akira Kurosawa at Toho in the early 50s, of course, got his breakthrough with Gojira, a film that would define his career to come. While he was still doing light drama and comedy throughout the 50s, after 1960, he made almost exclusively so-called tokusatsu or special effects films. Honda initially fought against bringing back Godzilla to the screen. On the one hand, of course, it was illogical, as we had seen Godzilla disintegrate in the first movie. But, furthermore, Godzilla represented something special to Honda, as the first movie had been a grim parable about the Japanese experience of WWII, and one that one can imagine that Honda felt wary about exploiting for kiddie-friendly commercialism. Instead, Honda wanted to bring out new monsters for his movies, which is how we get Rodan, Anguirus, Varan, Gigantis, Mothra and Gorath before Godzilla finally made a comeback in 1962 with King Kong vs. Godzilla.

In between the classic kaiju films, Honda also made a series interesting science fiction movies, including alien invasion films like The Mysterians (1957, review) and Battle in Outer Space (1959), submarine movies like Atragon (1963) and Latitude Zero (1969), as well as the more low-key so-called “transforming human” films: The H-Man (1958, review), The Human Vapor (1960) and Matanga (1963), which remains some of his most interesting pictures. But what he will be most remembered for are Toho’s most revered kaiju films, from Gojira to King Kong vs. Godzilla, Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster (1964) and Destroy All Monsters (1968). By 1975 he thought the quality of Toho’s kaiju movies had degenerated so badly that he went into retirement, and only returned brielfy to directing in the 90s in order to collaborate with his old friend and mentor Akira Kurosawa.

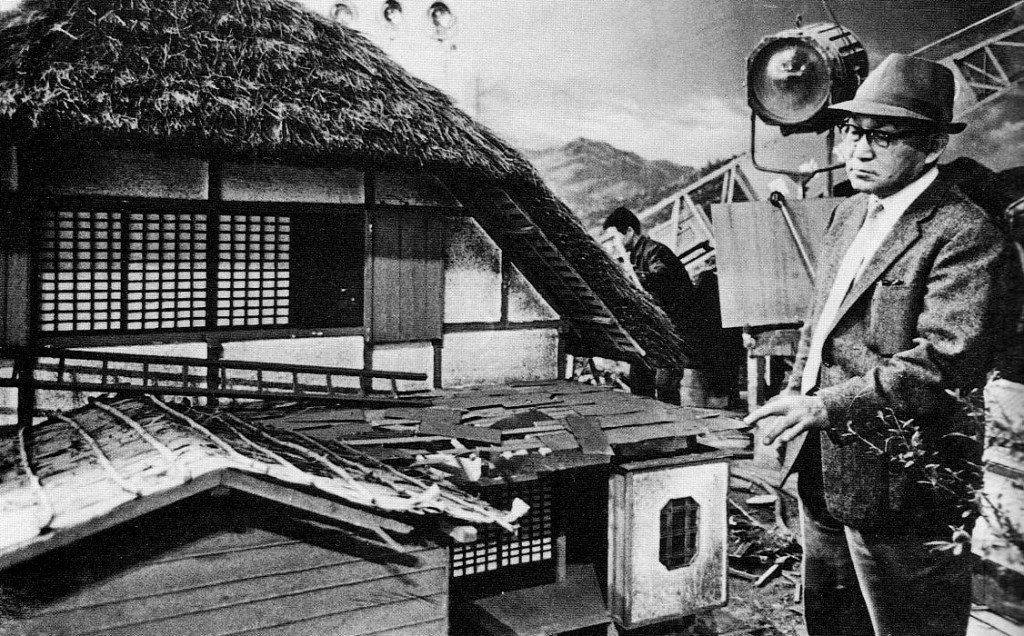

Special effects legend Eiji Tsuburaya was an engineer by trade, but his love for movies led him to work in the burgeoning Japanese film industry as a cinematographer at the age of 18 in 1919. He soon became one of the country’s leading filmers, and his background in engineering led him to design several technological innovations. For example, he designed Japan’s first camera crane, was the first to use full-screen rear projection and designed Japan’s first optical printer. Watching King Kong in 1932 (review) sparked Tsuburaya’s love for monster movies – and his interest in special effects. Over the years, he acquired prints of King Kong and numerous other American special effects movies and sat for days on end trying to figure out how the effects were done.

Toho was founded in 1936, and in 1937 Eiji Tsuburaya was hired to head Japan’s first special effects department. During the 40s he continued to push the boundaries for Japanese special effects, not least with propaganda films during WWII, where he gained much experience with destroying miniature buildings, which would serve him well in the future. However, after the war, the same propaganda movies got him briefly fired from Toho by the American occupators. But that didn’t slow him down, and he founded his own special effects company. It was during this time he made the effects for Japan’s oldest surviving science fiction movie, Daiei’s The Invisible Man Appears (1949, review).

However, after the occupation was lifted, Eiji Tsuburaya was quickly re-hired by Toho, where he worked as the cinematographer on Japan’s first 3D movie in 1953. In the early 50s he also started working with producer Tomoyuki Tanaka and Ishiro Honda, with who he would create Toho’s greatest hit throughout history in 1954: Gojira. The movie, a stark parable of Japan’s experience of WWII, took its inspiration from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review) and King Kong, but let the giant prehistoric monster represent the spectre of war and the nuclear bomb. Tsuburaya had originally intended to create the monster through stop-motion animation, but realised he didn’t have the resources needed for such an undertaking, and instead decided to use the tried-and-tested method of having a man in a suit. However, no-one had quite done the suit monster in such a way as Tsuburaya before, combining the man in a suit with elaborate miniature photography. This “new” technique was dubbed “suitmation”.

When Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (review) hit American audiences in 1956, the world caught kaiju fever, and Toho’s special effects department went into overdrive. Between 1956 and his death in 1970, Eiji Tsuburaya churned out effects for close to 100 films, a majority of them kaiju and science fiction movies. But in between he also had time to do work in a plethora of other genres, including Throne of Blood (1957) and The Hidden Fortress (1958) for Akira Kurosawa. In 1963 he founded his own company, dividing his time between this and Toho. For his own company, he created the TV series Ultra Q in 1964, which was eventually renamed Ultraman for its superhero protagonist. At the time it was Japan’s most expensive television show, and became one of the country’s most popular and influential shows. Constantly working, Tsuburaya refused to slow down despite suffering a stroke in 1969, and passed away from heart failure in the beginning of 1970.

Eiji Tsuburaya is rightly hailed as one of the most influential special effects creators in history. He pioneered many techniques in Japan through studying Hollywood movie making, but when it came to his most lasting legacy, it came down to simply trying to emulate as best as he could Hollywood effects without Hollywood resources. In his attempt att recreating the monsters he had seen on screen with the money and know-how he could muster at Toho, he inadvertedly created a whole new subgenre.

The cast of Varan has a few kaiju and tokusatsu stalwarts, however because of the low budget and the fact that none of the Japanese stars would be familiar to a US audience anyway, most of the leads are inhabited by cheaper character actors. For Kozo Nomura, this was the only “lead” he ever played, as he was mostly stuck in bit-parts. Female lead Ayumi Sonoda only appeared 13 films, two of them sci-fi movies. She appears as the exotic dancer who gets eaten by a blob in The H-Man (1958, review), and as the reporter investating the death of her brother in Varan (1958). The biology professor in Varan is played by Koreya Senda, a character actor also normally confined to smaller roles.

Akihiko Hirata turns up in a small role as the bomb expert. Hirata, of course, was the tortured scientist at the forefront of Gojira, who sacrifices himself for the good of humanity in the end. The role turned Hirata into a star, and he subsequently went on to star in numerous science fiction and monster movies. Yoshio Tsuchiya played one of the heroic pilots in Godzilla Raids Again (1955, review), and the leader of the aliens in The Mysterians (1957, review). Tsuchiya was one of Toho’s biggest stars and could have his pick of roles, but he was so fascinated by science fiction movies that he turned up in them time and again.

In smaller roles we see people like Hisaya Ito, Yoshifumi Tajita and Shoichi Hirose, who were all staple character actors in Toho’s tokusatsu films. Perhaps the most impressive performance of the movie is given by Noriko Honma, as the distraught mother of a boy from the superstitious village in the beginning of the film, who wanders off into the forbidden territory. Honma was a favourite of Akira Kurosawa, and appeared in films like Rashomon, Ikiru, Seven Samurai and Yojimbo.

Monster suit duty on Varan was, as usually, handled by Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka.

Janne Wass

Daikaiju Baran. 1958, Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Sinichi Sekizawa, Ken Kuronuma. Starring: Kozo Nomura, Ayumi Sonoda, Koreya Senda, Akihiko Hirata, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Fuyuki Murakami, Minosike Yamada, Hisaya Ito, Yoshifumi Tajima, Haruo Nakajima, Katsumi Tezuka. Music: Akira Ifukube. Cinematography: Hajime Koizumi. Editing: Kazuji Taira. Production design: Kiyohsi Shimizu. Special effects: Eiji Tsuburaya. Visual effects: Hiroshi Mukoyama. Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka for Toho.

Leave a comment