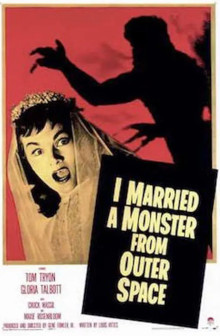

Aliens body-snatch the men of a small town so they can mate with Earth women and save their dying race. Despite it’s silly title and premise, this 1958 Paramount production is a surprisingly intelligent, well-filmed and atmospheric alien invasion thriller with a risqué sociological subtext. 7/10

I Married a Monster from Outer Space. 1958, USA. Produced & directed by Gene Fowler. Written by Louis Vittes. Starring: Gloria Talbott, Tom Tryon, Ken Lynch, Alan Dexter, Robert Ivers, Valerie Allen, James Anderson. IMDb: 6.3/10. Letterboxd: 3.2/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 6.5/10. Metacritic: N/A.

On his way home from his stag night at the local bar, Bill Farrell (Tom Tryon) hits a body on a forest road, but when he gets out of the car, the body has disappeared. Instead, a glowing insectoid hand reaches out for him, and he crumples beside his car and is pulled out of frame. The next day he arrives at his wedding late and seemingly bewildered. However, his marriage to Marge Farrell Bradley (Gloria Talbott) goes through as planned. But when the couple go on their hotel honeymoon, Marge notices that something is clearly off with Bill, who acts in a weirdly emotionless and manner. What she doesn’t see is that when lightning illuminates his face on the hotel patio, it reveals a hideous alien monster underneath his skin.

Don’t let the exploitative title scare you away from this one. Paramount’s 1958 effort to shoehorn themselves into the teenage science fiction market is significantly better than its drive-in oriented name suggests. In fact it has more in common with Invasion of the Body Snatchers than with Invasion of the Saucer Men.

There’s really no point in describing the plot of this movie in detail, as the film is more about character than plot. But the basic premise is this: Aliens from an unnamed Planet X in the Andromeda galaxy have travelled to Earth in order to mate with Earth women. Like the Ents, these aliens have lost their women, and set out on a desperate voyage across space in order to find a species they can have children with.

If this description shows them in a sympathetic light, this is not what the movie is going for, at least not in the beginning. We are made aware that the aliens seem to inhabit the bodies of the males that they abduct. They enter and exit the bodies as a thick, oily smoke. When they exit their vessels, the bodies they leave behind are dead. When exiting the hosts, the aliens take on their true forms, as sort of vaguely resembling Davy Jones from Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006).

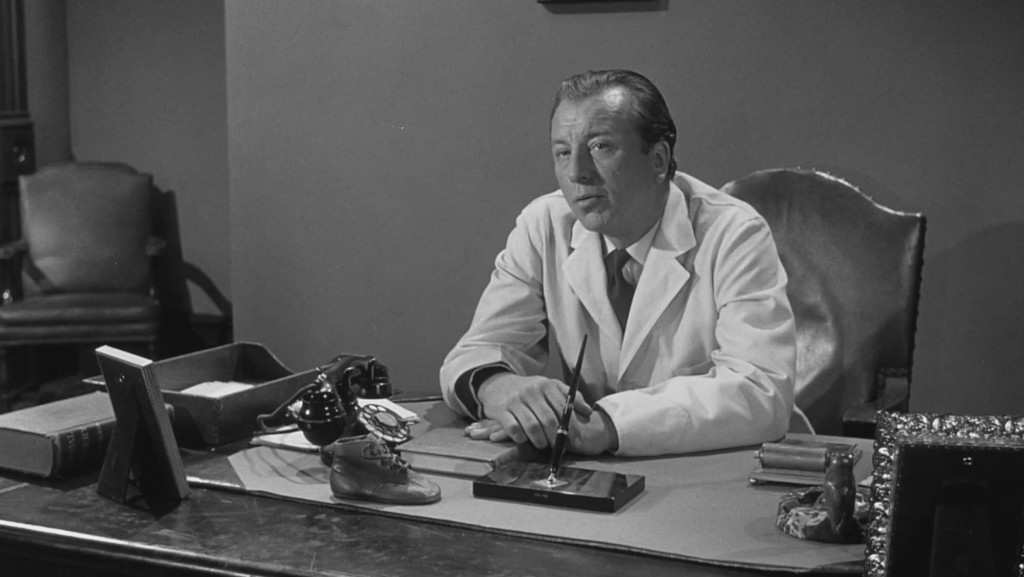

I Married a Monster from Outer Space is unusual for its type inasmuch as it is the female lead who is the true protagonist of the piece. The film follows Marge, as she comes to realise that Bill is no longer the man she married. While he plays at the loving husband, he is cold and distant. He has lost his taste for alcohol and no longer goes out drinking with his buddies. Dogs used to like him, but when Marge buys him a puppy, it instinctively takes a fierce disliking to him. Later the dog is found dead under mysterious circumstances. More importantly, despite trying to get a child, a year goes by without Marge managing to get pregnant. She visits her doctor Wayne (Ken Lynch), who tells her that her reproductive system is normal, and she should have no obstacles to getting pregnant. Instead he suspects that the problem might lie with Bill. When she suggests Bill go see the doctor, he tenses up.

Everything changes one night when her suspicions grow too powerful and she shadows Bill on one of his nightly walks, when he thinks she is sleeping. She follows him to the nearby forest, where she sees the black smoke exiting his body and morphing into its alien form, before entering the door to a UFO. When she runs up to the now empty body, it is devoid of all life. Distraught, she seeks help from the locals at the bar and from the police, bit no-one seems to believe her. Desperate, she tries to send a telegram from the local telegraph office to the FBI, but as she leaves, she sees the telegraphist throwing her message into the wastepaper bin. She realises that it is not only her husband that has been taken over by aliens, but several of the men in her small town, perhaps all of them.

At the same time, more and more of men in her husband’s group of friends begin acting strangely, and suddenly the bachelors who all swore never to submit to the ball and chain of marriage, start to tie the knots with their girlfriends. Finally, she confronts Bill, and he spills the beans, telling her of his home planet and the aliens’ reasons for coming to Earth. The reason she has not been able to get married is that the two species are not compatible. But, says Bill, their scientists are currently working on experiments to mutate the ovaries of human women, so that can give birth to alien babies. The question is not if Earth’s women will become mothers to an alien race, but when. But there is a hitch: in taking over the bodies of Earth men, the aliens are also changing, as they are starting to develop human feelings, even slowly learning to understand love.

Later, when the group of friends convene at the beach – the men now almost all aliens, and their wives blissfully unaware, one of the alien men fall out of a boat. Despite having previously been an expert swimmer, the man flails in the water and is about to drown, before he is rescued. Dr. Wayne is on hand, and provides him with oxygen. Strangley, the oxygen doesn’t save him, but instead kills him, confounding the doctor. This is when Marge takes the chance to trust the doctor, and later visits him, telling him all about her experiences. While skeptical, Dr. Wayne chooses to believe her. Wayne then rounds up all the men who have recently become fathers, and are thus sure to be human, and leads a raid to the UFO, where they encounter alien guards. Guns do not harm them, but the two german shephards they bring along attack the monsters, ripping the tubes running adoring the alien’s faces, which kills them. Inside the UFO they discover the bodies of abducted men, including Bill’s, and realise that the men that have been inhabiting the town are in fact copies. Dr. Wayne theorises that men are actually in a sort of stasis, and that the copies are created by feeding electrical impulses from the originals. If unhooked from the devices they are attached to, the copies should die. Said and done, and the team begin unplugging the males, who are all still alive.

Meanwhile, aliens in town realise the jig is up, and race towards their spaceship, but one by one, they start collapsing, and the bodies turn into jelly that ooze out of their clothes. The last body to be unplugged at the UFO is Bill’s. He reaches the UFO in time, and when he sees what is going on, he drops his deadly ray gun, and surrenders in order to say farewell to Marge. After he collapeses, the real Bill is brought out of the UFO, and now, presumably, is able to marry Marge for real. As the film concludes, the town’s chief of police (John Elderedge) contacts his alien superiors, and before he too turns into goo, he concludes that Operation Earth has failed, and recommends the fleet move on, in hope of finding another planet where they can enslave the men. The film ends with a shot of the alien armada leaving Earth.

Background & Analysis

By the late 1950s small studios like American International Pictures and Allied Artists were making a killing at the drive-in theatres in the US with cheap exploitation fare: primarily teenage delinquency films and science fiction movies. Sensing a lost opportunity, major studios who had previously had little interest in the SF genre, wanted a slice of the pie, and shoehorned themselves into the already saturated market. United Artists were already a semi-regular player in the field, as was Fox, releasing their “B+” pictures through Robert Lippert’s sister company Regal Pictures. Paramount and MGM largely filled their quotas with imports from the UK and Japan. However, in 1958 Paramount decided to produce a movie of their own, perhaps in order to have a suitable companion for The Blob (1958, review), which they had purchased from its independent religious production company. This was I Married a Monster from Outer Space.

According to an interview in Fangoria, director Gene Fowler took the initiative to the film after the huge success of his previous science fiction movie, the surprisingly good I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review). The story of the film, and probably the title, came from Fowler, but he called up his frequent collaborator Louis Vittes to write the screenplay. Fowler says that the duo deliberately chose a cheesy title in order to lure people to the theatres, and admitted that the premise was ridiculous. Fowler makes no excuse for the fact that they were making an exploitation picture, but he says that he nevertheless wanted to make a good film, and take the both premise and the movie seriously: “If you accept the thing as very realistic and very honest, then you can come up with very honest performances and make a fairly honest picture out of it”. The title of the film, of course, is partly meant to evoke the teenage monster movies that AIP had had such a success with, starting with Fowler’s werewolf movie – but may also be an allusion to RKO’s controversial 1949 film I Married a Communist.

The inspiration for the movie is clearly taken from Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review) and Invaders from Mars (1953, review). In fact, the movie comes dangerously close, at times, to appearing as a ripoff of the former. However, it has enough of an identity of its own to clear itself of such accusations.

I Married a Monster from Outer Space was filmed over ten days with a budget of $175,000, a very low sum for a Paramount production. However, Gene Fowler, who also produced the film, still had the resources of a major studio at his disposal, which gave him an edge over the producers at AIP, which didn’t even have their own studio facility. Much of the movie was filmed on standing sets at Paramount’s sound stages and backlots, giving it a more expensive feel than its budget would suggest. Fowler could also count on both the special effects and visual effects departments to deliver quality content even on a small budget. The monsters were reportedly designed by monster makeup legend Charles Gemora, and the visual effects are credited to John P. Fulton, who had done such groundbreaking work with Universal in the 30s.

The aliens look pretty good, even though they are not particularly innovative. Here Fowler and Gemora have resorted to the cheapest and simplest solution: men in rubber suits. But the tubed faces and long-fingererd tentacle/pincer-like hands are very creepy. According to Fowler, the tubes were originally meant to be part of a breathing apparatus, but somewhere along the design process there was a communication breakdown, and they instead became parr of the aliens’ physiognomy. Originally the aliens also wore short pants, but reportedly lead actor Tom Tryon thought they looked so silly with them on that he refused to be in the frame with them. So instead they got full pants. Budget restrictions are especially apparent in regards to the flying saucer, of which we only ever see the entrance: the rest is hidden in the foliage. The spaceship interior on display is limited to a single nondescript room, where the abducted people are suspended from piano wires above something which one reviewer thought looked like video game consoles (back in the day). The effect of the goo oozing out of the body duplicates’s clothes when the originals are detached from the UFO in the end are also effective, if simple. In fact, it was Jell-O cooked up by Mrs. Fowler.

There are three main visual effects in the film. The first and most memorable is when the alien faces flash through the body doubles’ faces. It’s a rather simple matte effect, but well executed and very startling the first time it occurs – which is partly thanks to the Fowler’s skill in building atmosphere and editing. Then there is the white glow which covers the aliens. This was probably done in order to give the monsters a more other-worldly feel, rather than the obvious actors in rubber suits that they were. It feels like a somewhat cheap solution and not quite worthy of the skill of the Paramount team. The final main effect is the black smoke that invades the humans. This is an extremely ambitious effect, as it is done through matte work, and smoke is pretty much impossible to matte convincingly. The effects do suffer somewhat from their sharp matte lines, but on the other hand, this is no ordinary smoke, so you do buy it as a viewer.

As stated, John P. Fulton is credited as the special effects artist in the movie. Anyone who knows their classic horror movies knows that Fulton is the man who created the effects for all the 30s and 40s Universal monster movies, and he is especially revered for his work on the groundbreaking The Invisible Man (1932, review). However, by the late 50s, Fulton had jumped ship and was working as head of the special effects department for Paramount. With a name like Fulton involved, it is no surprise that the effects are top-notch. However, there are film buffs that have questioned whether Fulton, as the head of the special effects department at a major studio, would really have been working on a $175,000 movie himself – especially as he was kept busy working on Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo at the same time as I Married a Monster from Outer Space was in production. His name would still appear in the credits, even if he had nothing to do with the picture, as it was the custom in this era that department heads were credited, regardless of who did the actual work. So whether it was actually Fulton or merely someone on his staff that created the effects for the movie we may never know.

But the effects, impressive though they are for a low-budget movie, are not really what make I Married a Monster from Outer Space stand out in the deluge of low-budget monster and science fiction movies flooding cinemas in the late 50s. No, it is the unusually – for a low-budget exploitation movie – intelligent script and Gene Fowler’s stylish direction.

Considering that the awful Monster from Green Hell (1957, review) was screenwriter Louis Vittes‘ only other science fiction collaboration, it is downright astounding that the script for I Married a Monster from Outer Space is as good as it is. Granted, we don’t know how much of a hand Fowler had in the writing – but he doesn’t have a script credit. Don’t get me wrong, this screenplay certainly isn’t Oscar material, and has its share of clunky dialogue, ridiculous plot conveniences and holes in logic. The “Mars needs women” trope is pure exploitation – even if it wasn’t nearly as prevalent in 50s SF movies as posterity would have us believe. And there are several tropes that feel a worn-out – the fact that Marge is trapped in a small town and the film contains scenes of her trying to place a call to the authorities without luck and trying to leave by car, only to be confronted by road blocks, feel like repetitions from countless other alien invasion films.

But like it’s most prominent inspiration, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the picture benefits from its multiple layers of subtext – and like Body Snatchers, the fact that it doesn’t hit you over the head with a message, but is, at least to some extent, open to interpretation. What also makes the film stand out is that it is told from the perspective of a woman. While it wasn’t unheard of, a female perspective was exceedingly rare in Hollywood science fiction movies in the 50s, as they were almost inevitably relegated to the role of damsel in distress or to that of a “walking refrigerator” that needed to be reminded that what she really wanted to do with her life was to wash a man’s socks and birth him children.

I Married a Monster from Outer Space is really all about marriage, gender roles and expectations. The film follows Marge, who makes the startling discovery that her husband changes completely the day she marries him, a man not to be loved, but to be feared. Many have found in this storyline an exploration of domestic abuse toward women, and the film was rediscovered by feminists in the 70s as a sort of proto-feminist work. The problem of domestic violence, physical and mental, is still a major issue today, and would have been doubly worse in the 50s in the US, due to the prevailing gender norms and the draconian divorce laws in place in many states. In regards to this theme, the film bears some resemblence to another 1958 movie – Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (review), a picture that almost despite of itself said something intelligent about dysfunctional marriages and marital abuse. It’s not that I Married a Monster necessarily adds any depth to the discussion of marital abuse, but the way in which it depicts Marge’s growing sense of unease that mounts into terror and the feeling of entrapment makes you really feel her situation. The script deftly builds the tension through scenes in which her paranoia and later desperation slowly escalate, until she realises she might be completely alone. This theme was surely a sensitve one in the 50s, and not one that was expected to turn up in in a sci-fi B-movie.

But more than that, the film is a treatise on marriage as an institution and a social phenomenon, as well as about gender roles. When we meet male lead Bill and his friends in the beginning of the film, they are celebrating Bill’s stag night at the local watering hole, which the film portrays as the place where they spend most of their free time. All the young men at the table display negative attitudes toward marriage – both the married ones and the unmarried ones. It’s the old ball-and-chain, the end of youth and freedom. None of them seem particuarly enthusiastic about marriage, but still all treat the subject as one of the certainties of life: they will all be married one day.

Then along come the alien body snatchers, either taking over the lives of the men who have recently gotten married, or the singles, who then promptly get married. Thus: the change in the men’s behaviour coincide with their marriages, carrying a symbolism that can’t be coincidental. The once carefree, jovial young men, full of joie de vivre, become dull, moody and boring – they even lose their taste for the alcohol they so happily chugged down before marriage. In this sense, the aliens simply confirm the men’s doubts about married life. Women, on the other hand, seem to all be longing for marriage. This is exemplified by Marge’s friend Helen (Jean Carson), who is one of the women who gets a surprising marriage proposal after one of Bill’s friends is body-snatched, and expresses her relief that she doesn’t have to get a job.

I Married a Monster from Outer Space offers a curious glimpse into the 50s discourse about marriage. This, after all, was the decade in which marriage as an all-American institution was cemented, as part of the push for so called “traditional” family values. On one hand, marriage was touted as the central component of the white, middle-class, suburbian nuclear family ideal. A marriage, a house, two kids and two cars was advertised as the fulfilment of a life, the key to a lifetime of happiness and comfort. But on the other hand, it was also the end of the line. Once the knot was sealed, the general consensus was, a life of duties and routines awaited.

Of course, this was all a part of an on-going campaign from the top of the political ladder, and trickling down through powerful commercial interests, to re-shape the mental landscape of the US. In part, the promotion of conservative values was a way to keep a growing subculture of resistance at bay: feminism, the civil rights movements, unions and a growing socialist movement were threatening the powers that be, in particular the people holding the capital and those in power supported by this capital. The conservative middle-class life of happy and docile consumers, finding fulfilment in TV dinners and a new Hoover, was promoted as the pinnacle of the American dream.

However, curiously, I Married a Monster from Outer Space shines a light on a public opinion that wasn’t sold on the dream that was being sold to them. For many, surely, this proposed way of life must have felt like the promise of a strait-jacket, both men and women – not speak, of course of non-binary people, that didn’t even officially exist in the 50s. Also, curiously, the film focuses on male anxieties in regards to marriage – disregarding the fact that the ball and chain were in actuality worn by the wives and not the husbands.

Another interesting aspect of the film is that it explicitly tackles the issue of sex – and of male impotence, which must have been a topic that was quite rare in 50s public discourse, not to speak of Hollywood movies. As per the production code, of course, the sex is merely implied, and we never see Bill and Marge share a bed. Their marital bed, in fact, is not one, but two separate beds. The film takes on a much darker note when you consider that Marge is, in fact, having sex with a man she fears and feels is a stranger – or in the language of the film – an actual alien monster.

What is less clear is what the takeaway of the film is. While it certainly has what must be interpreted as some form of feminist themes, these seem to dissipate once we move towards the film’s climax. The last 20 minutes of the movie are more within the lines of the classic 50s B-movie, and is primarily invested in finding and killing the aliens, setting the body-snatched men free. The ending, where Bill is reunited with Marge, and they presumably head off to do a re-over of their wedding, only works to reinstate prevailing conservative norms.

Viewed from a cold war lens, one can see the aliens as the threat of communist infiltration. This is very much in line with the oft-repeated image of communists in science fiction movies as emotionless representatives of a mechanically thinking, enslaved hive mind. Interestingly, though, screenwriter Vittes does not quite portray the individual aliens in this light. Instead, he gives them all personalities of their own, and even lets them argue amongst themselves about how to go about achieving their goals. One of them hates being trapped in his human body, while another confesses to actually enjoy the life of a human. Bill’s stand-in wallows in depression and doubt, and even seems to have second thoughts about the mission. Having learned about love, friendship, and – if we carry through with the cold-war angle – freedom and the American way of life, Bill’s alien ultimately chooses self-sacrifice over his mission. And even though their mission is ultimately evil from the point of view of the human population, the aliens themselves aren’t portrayed as evil. They don’t seem to have any ill will as such toward humans, but have hatched their plan simply as a desperate, last-ditch gamble in order to save their species. While he is cold and distant, Bill’s alien never shows any signs of being prepared to physically harm Marge, and if he mentally harms her, he doesn’t seem to be doing so deliberately.

All in all, this is a film that can be interpreted in a number of ways, one that highlights surprising and sensitive themes far outside of the Hollywood mainstream, and that does so with a reasonable amount of intelligence. Partly, one assumes, the film reveals more of the social norms and anxieties of the time than it intends to, inadvertedly. But part of it is clearly intentional. Unfortunately neither Louis Vittes or Gene Fowler is able to follow through on these themes all the way to the conclusion of the movie, when it falls back on conventional tropes.

There are several standout scenes. One comes fairly early, when “Bill” and Marge are on their honeymoon, watching a nocturnal vista over a bay from their hotel balcony. You can literally feel the tension in the air, and a feeling that something is off kilter, with “Bill” acting just odd enough for Marge to become suspicious, and the strange but obvious atmosphere that this is not a young couple in romantic bliss, but two people who are distant and strangers to each other. The cinematography and editing in this scene is perhaps the most sublime in the movie – and when we first see “Bill’s” true face illuminated by lightning, it is quite a shocker. Another great scene comes when Marge sees the alien leave “Bill’s” body, and runs up to him, finding only a blank face staring out into the distance, an empty shell of a man, who falls to the ground like a plank at her touch. Good is also the scene where the town prostitute Francine (a great Valerie Allen) – whom we have spent enough time with to care for – seeks a potential customer with a hooded figure with his back towards the camera looking at a storefront window in the night. Fowler lets the scene unfold slowly, with Francine egding ever closer to the figure, until he turns – towards her, not the camera – and we slowly see Francine’s expression turn from disbelief to terror, and then finally a scream. And then the camera show us the tubular face and the insectoid hand reaching for Francine. And this is where we see the aliens’ disintegrator ray in action for the first time. Importantly, since we know and like Francine, the death means something.

But it’s not only the effects and the script that is above par in I Married a Monster from Outer Space. Director Gene Fowler is also a better-than-usual director of this kind of movie. Fowler was primarily an editor, and cut several films for noir master Fritz Lang. Fowler was also a close personal friend of Lang’s, and considered the demon director his mentor when it came to directing. Influences of Lang’s expressionist lighting are clearly on display in I Married a Monster, including Fowler’s use of shadows, spotlights and the lighting and turning off of lamps, etc, to use light – or the absence of it – as a tool for storytelling and metaphors. The editing of the film is also top notch. No surprise here: not only is the director one of Hollywood’s top editors, the editor of the film is George Tomasini, who edited nine films for Alfred Hitchcock. And as the cherry on top, cinematographer Haskell Boggs went on to earn five Emmy nominations, in particular for his work on Bonanza.

Not everything here is great. As stated, the script has its fair share of plot holes. Why can’t the aliens body-snatch women? One would think that would make their plan a whole lote easier. Why do they go through the whole charade of marriage, instead of just kidnapping a few women and go about their business? Why do the aliens insist on meeting at the bar and order drinks, even though they raise suspicion by not drinking? Why do they body-snatch all the authorities in the small town, except the town doctor, who is the most likely candidat to spot their biological anomalies? Why do bullets bounce off their skin but not canine fangs?

Plus, as mentioned, the themes and ideas of the movie pretty much dissipate into thin air by the final third of the movie, and none of them are really ever brought to a closure. There are characters and subplots who are likewise left hanging. The great James Anderson turns up a bit into the picture, as an outsider, a gangster-like character, who is the first person to actually believe Marge, and suspect something sinister is going on in the town. He is set up as a potential second lead in the film, and brings a good energy to the proceedings, that I would have liked to see more of. But he is unceremoniously killed off halfway through, without his character having had the opportonity to have any sort of impact on the plot.

The acting is also good across the board. Make no mistake, this is Gloria Talbott’s film, and probably one of her finest performances. Talbott treads the line between between victim and heroine with great skill, and it is her electric performance that pulls the audience into the story, accepting the outlandish premise. Talbott plays the character with an openness and emotional depth makes the viewer part of her growing horror and paranoia, and her sympathetic portrayal creates an instantly likeable performance.

Tom Tryon is at least serviceable in the lead. The role doesn’t demand all that much of him, and in his subdued, emotionless performance, he is able to create a believably threatening and creepy character. Valerie Allen as the sympathetic prostitute Francine gives a standout performance. She is perhaps the most likeable character in the movie, and thus her death packs a real emotional punch. James Anderson is great as the gravelly, mysterious scoundrel that is set up as a heroic character. It is too bad that his character is killed off rather unceremoniously halfway through – it would have been interesting to see more of him, and his presence could have created an interesting dynamic.

The rest of the cast is all made up of competent character actors. Ken Lynch gets a lot of screentime as the doctor who rallies the town’s dads to fight off the alien invaders, Alan Dexter is memorable as one of Bill’s friends who gets bodysnatched (he’s the alien that enjoys being human) and John Eldredge gets a couple of good scenes as the sympathetic police chief who comforts Marge, but turns out to be an alien himself. There’s a fun cameo by boxing champion turned character actor Maxie Rosenbloom as the local bartender and western hunk Ty Hardin as one of Bill’s bachelor friends. According to some sources, suit designer Charles Gemora wore one of the alien suits. However, I am skeptical, as the aliens are portrayed as quite tall, and one of the suit actors, Joe Gray, was 6 feet/183 cm tall, while Gemora stood at 5’4, or 163 cm.

Despite its flaws, I Married a Monster from Outer Space is a film that is far better than its sensationalist title would imply. As far as technical and artistic values go, the film stands head and shoulders over most low-budget fare of the era. The direction by Gene Fowler might be the best of his career, the lighting and editing is top-notch, and supported by a good cast who all take the picture seriously. It is a genuinely suspenseful and occasionally even disturbing movie, touching on several themes that were quite risqué at the time. It benefits from its layered approach to the themes, with a script lending itself to multiple interpretations. Nevertheless, its central idea may just be a tad too ridiculous to take entirely seriously, and the many interesting ideas are not quite brought to satisfying conclusions, as the movie degrades into more of a traditional alien hunt toward the end. The fact that so many of the proceedings feel like retreads of earlier films also eats at its originality, and creates an odd sensation of deja vu. Still, this is one of the best science fiction movies of the late 50s, sadly tarnished by its sensationalist title.

Reception & Legacy

I Married a Monster from Outer Space premiered in the US in October, 1958, as the top bill in a pairing with The Blob (review), which Paramount had bought from producer Jack Harris. While The Blob is arguably an inferior film, its tongue-in-cheek attitude and memorable Technicolor monster quickly proved more popular with the teen crowd than the ponderous seriousness of I Married a Monster, and Paramount reversed the billing of the two pictures to fit. The double bill went on to do tremendous box-office business, although credit for this should probably go to The Blob. The film was released in large parts of Europe in the fall of 1959.

The movie received generally positive reviews in the trade press. Harrison’s Reports said that the film was “more imaginative” than most science fiction films being released at the time, and that “the action unfolds in suspenseful fashion and holds one’s interest well all the way through”. Whit in Variety noted “strong plottage” and “outstanding photographic effects”, and also praised the acting, the editing and Gene Fowler’s suspenseful direction, even if he though it was a tad slow at times. At The Hollywood Reporter, Jack Moffitt thought I Married a Monster was “fairly interesting and intelligent”. British Monthly Film Bulletin, employing an odd 3-1 rating, where 1 was best and 3 worst, gave the film a 2 rating: “This generally well-acted and -staged Science Fiction thriller, though novellettish in its personal story, has an intriguing situation and some effective, if rather sparse, trick camerawork. […] the overall treatment, though polished, is a bit short on action and excitement.”

As of writing, I Married a Monster from Outer Space has a fair 6.3/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on a decent 3000+ votes and a 3.2/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on 2000+ votes, representing a generally positive reception by modern audiences. Critics at Rotten Tomatoes give it a 92% Fresh rating, with a weighted average of 6.5/10, making it a film fairly well-liked by critics as well.

TM at TimeOut calls the picture “a remarkably effective cheapie about an alien takeover, which even manages an undertow of sexual angst” and notes “Good performances, strikingly moody camerawork, a genuinely exciting climax”. In his book Keep Watching the Skies, Bill Warren cites a routine storyline and some clichés, but feels that the characterisations, the development of the story of the capable direction make for “an interesting, smooth and scary science fiction-horror thriller”. A Moria, Richard Scheib gives it 3/5 stars. He opines that director Fowler was much more pedestrian than directors like William Cameron Menzies and Don Siegel, whose films had such an inspiration on I Married a Monster, but continues: “That said, there are definitely times when Gene Fowler transcends the material with a fervid pulp imagination”. Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant is mildly positive but not overwhelmed, citing “good acting and okay plotting” and “souped-up production values”. Overall, Erickson isn’t particularly impressed: “The movie generates some suspense but never the desired level of paranoia”.

There has been some discussion over the decades about the feminist merits of I Married a Monster from Outer Space, nicely summed in Warren’s book. Critics and film historians like John Brosnan and David Hogan have read strong feminist messages into the movie. In his book Future Tense, Brosnan writes that the film represented “the ultimate feminist nightmare that lurking behind the handsome facade of one’s husband is a foul monster whose only interest is the exploitation of the female body”. Hogan, for his part, wrote in Cinefantastique magazine that the script emphazises the subservient position of women, and notes that no-one believes Marge, in his interpretation, because she is a woman. Bill Warren interjects that Fowler and Vittes probably weren’t out to write a feminist manifesto, and that it was inherent in the plot of any alien invasion film that no-one believes the protagonist who is convinced that aliens are snatching our bodies. And in most films, these protagonists were male. Plus, Warren points out: if this was really intended as a feminist manifesto, why doesn’t Marge turn to he wives of the body-snatched husbands for help?

Richard Scheib suspects the filmmakers were more interested in the concept of marriage than sex: “It was clearly written by someone who was either a bachelor whose greatest fear in life was of getting married, or someone who had a fairly embittered view of marriage”. Scheib continues: “Unlike most treatments of sex and gender roles in 1950s science-fiction, I Married a Monster from Outer Space is divided on the subject – in the second half the attitude becomes markedly reversed to what it is in the first and it ultimately becomes a film about asserting traditional stereotypes. For all the earlier fear the film seems to exhibit about marriage, I Married a Monster from Outer Space is eventually a film that comes out with all red-blooded testosterone blazing in favour of fighting for commitment and the life of docile, sober anonymity.” He concludes: “There seem few films that reveal more aptly than I Married a Monster from Outer Space the fearful beliefs that ran through 1950s science-fiction of there being a force out there that lacked and could steal emotion away from ordinary people. Paradoxically, the film also reveals that the ordinary life that was being defended as the status quo was one equally threatening in its dictatorial demand for conformity – a place where men and women must both conform to ridiculously idealised notions of middle-class marriage, where the man is the provider and the woman must stay at home and make house.”

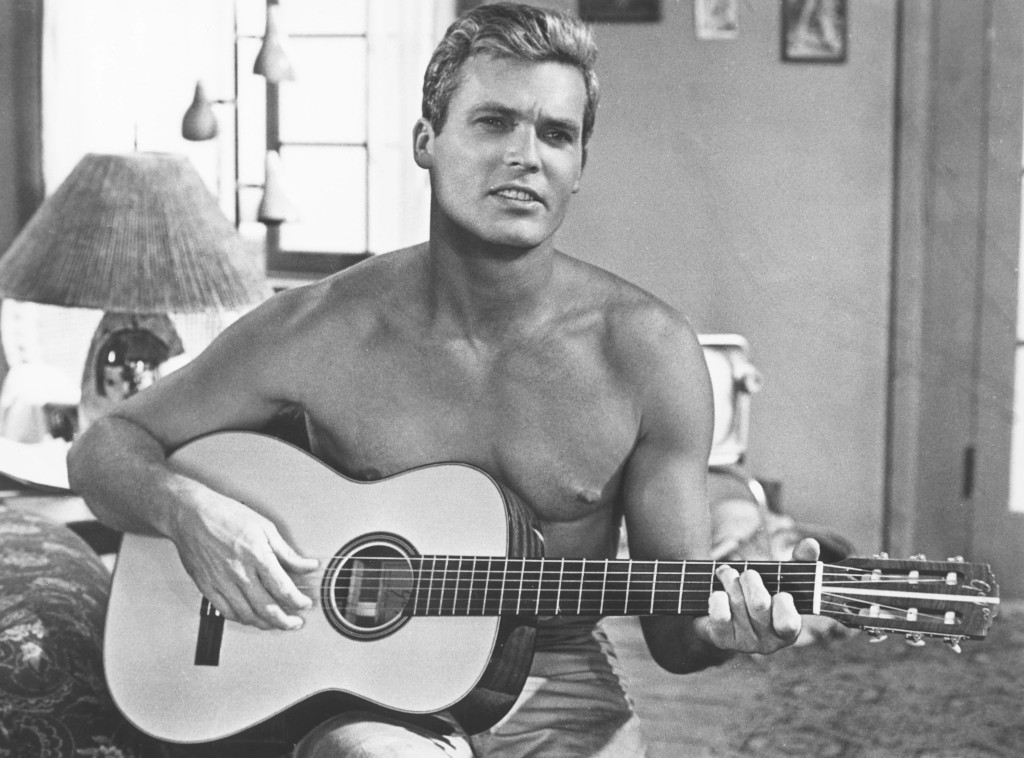

Film scholar Harry M. Benshoff instead suggests that the film features a blatant subtext of male homosexuality, citing Bill’s preference to “meet other strange men in the public park” rather than stay at home with his wife. He makes his claim in his book Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. One of the reasons that the film is sometimes analysed through a queer lens may be that lead actor Tom Tryon was a closeted gay man. Gary Westfahl, for example, has analysed his whole career and body of work through his homosexuality, much in the same way as people often want to see gay themes in all of James Whale’s films.

I Married a Monster from Outer Space was remade as a TV movie with the abbreviated title I Married a Monster in 1998, which has a largely negative reputation. Bill Warren also notes the similarities between I Married a Monster from Outer Space and the 1999 film The Astronaut’s Wife, starring Johnny Depp and Charlize Theron.

Cast & Crew

Gene Fowler was one of the top editors of Hollywood. He started his career in the 30’s, and in the 40 worked with directors like Fritz Lang and Samuel Fuller. All in all, he collaborated with Lang on four films: Hangmen Also Die (1943), Woman in the Window (1944), While the City Sleeps (1955) and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956). Fowler was also a close personal friend of Lang’s, and considered the demon director his mentor when it came to directing. Influences of Lang’s expressionist lighting are clearly on display in I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), including Fowler’s use of shadows, spotlights and the lighting and turning off of lamps, etc, to use light – or the absence of it – as a tool for storytelling and metaphors. It can also be clearly seen in his other well-made sci-fi/horror film, I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review).

After WWII, Fowler edited two renowned WWII short documentaries, the first was John Huston’s San Pietro (1945) and the second the propaganda movie Seeds of Destiny (1946), which won the Oscar for best documentary short.

Fowler did did some TV directing before getting his first chance at helming a movie with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), and directed a little more than half a dozen more movies in the 50’s, the best known being Paramount’s I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). In the early 60’s he directed some TV before returning to editing. As an editor he was Oscar nominated for his work on It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963), and won two consecutive Emmys for his TV work in 1973 and 1974. He allegedly also did some uncredited directing on the ill-fated SF movie The Astral Factor (1978), also released in reworked form in 1984 as The Invisible Strangler. Actress Gloria Talbott says that she liked very much working with Fowler: “He was a sweetheart, and it was a real delight, an actor’s dream, to work with him”. She says that she could see that Fowler really worked hard on and cared about the I Married a Monster, and would be exhausted toward the end of the shoot.

Screenwriter Louis Vittes was a capable writer for hire in Hollywood 1954 and 1969, and is primarily known for co-penning the sub-par giant wasp movie Monster from Green Hell (1957, review) and Paramount’s I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), a film that has a reputation for being better than its title would suggest. He also wrote over 30 episodes for Rawhide. In an interview with Tom Weaver, lead actress of I Married a Monster, Gloria Talbott, says that she was extremely frustrated with Vittes during filming, as he would sit by the camera every day and mouth the lines while the actors were working, and correct them every time they changed a word. According to Talbott, Vittes wasn’t being unkind, but was just so protective of his script being filmed by a major studio. Finally, Talbott had to convince the producer to talk to Vittes, explaining he was distracting the cast.

Gloria Talbott grew up in the town of Glendale just outside of Los Angeles, and started acting in school plays. She later founded her own drama group, and appeared in a handful of films as a child actress. In 1951, At the age of 20, she became a Hollywood regular, appearing in guest spots in TV and bit-parts in movies, slowly working herself up the ladder, until she was rubbing shoulders with Humphrey Bogart in We’re No Angels and Rock Hudson in All That Heaven Allows in the mid-50’s. This is when she also started getting cast in leading roles in B-movies, mainly westerns, partly due to her competence on horseback. She is best known as a scream queen in four genre films in the late 50’s and early 60’s: The Cyclops (1957, review) and its double bill Daughter of Dr. Jekyll (1957), I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) and The Leech Woman (1960). All the while, she worked steadily in TV, racking up over 100 TV credits 30 movies between 1935 and 1966. Then she called it quits, in order to get to spend time with her daughter.

In her interview with Tom Weaver, Talbott gives the impression that she enjoyed her time as an actress very much, partly because she never harboured dreams of stardom or bitterness when it didn’t present itself. She does give the impression that she would have liked a few more meaty roles in her career, but says that nevertheless, she was quite happy with the end result of films like The Cyclops and Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, considering the circumstances. Talbott has nothing but good things to say about working at Paramount with I Married a Monster from Outer Space (she was very enthusiastic about the paycheck) – apart from the screenwriter sitting and mouthing the lines throughout the shooting.

After being discharged from the US navy in 1946, 19-year-old Tom Tryon started working as a set designer and painter at a theatre in Massachusetts, before being encouraged to try it out as an actor, after which he started studying acting and made his Broadway debut in 1952, and moved to Hollywood in 1955. He becama a household name in 1958, when he starred in the Disney western series Texas John Slaughter, as part of the Disneyland TV show. The same year he also starred as the alien duplicate of Gloria Talbott’s husband in the surprisingly good I Married a Monster from Outer Space. Tryon was never an A-list name, but worked steadily and happily in films and TV shows throughout the 50s and 60s, but his life changed when he saw the horror movie Rosemary’s Baby in 1968. Inspired by the movie, he decided to try and write his own horror novel, and the result was The Other (1971), a novel set in the 30s about a boy with an evil twoin who is suspected of several murders in a small rural town. The book became an instant bestseller, staying on the New York Times book list for six weeks.

The next year, he adapted the novel for a screenplay, produced by 20th Century-Fox. By this time, Tryon had already left the acting business, and under his birth name Thomas Tryon penned several successful horror books, inlcuding Harvest Home (1973) and Crowned Heads (1976). A story from the latter was turned into the film Fedora in 1978, with Billy Wilder as director. Tryon was one of a number of closeted gays active in Hollywood during the 50s, and in 1958, the year I Married a Monster from Outer Space premiered, he divorced his wife of only three years. In the late 70s he had a relationship with porn actor and gay icon Casey Donovan. Tryon passed away from complications arising from HIV in 1991. I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) and the family comedy Moon Pilot (1962).

In a smallish role as one of Bill’s friends we see Ty Hardin. Born Orison Whipple Hungerford, he made his film debut earlier in 1958, in The Space Children (review), under the name Ty Hungeford. A square-jawed former college footballer, he would later change his name to Ty Hardin, became a TV star and an international movie star, made his way through eight wives, was jailed in Spain for drug smuggling and once noted: “I’m really a very humble man. Not a day goes by that I don’t thank God for my looks, my stature and my talent.”

Hardin was noted by a talent scout in 1957 when at a costume party dressed up as a cowboy. He was put under contract at Paramount and had small roles in films like The Space Children and I Married a Monster from Outer Space in 1958, but had a hard time getting his foot through the door. However, the same year, he moved to Warner, who put him on TV, where he created a stir as Bronco Layne in the western series Cheyenne. So popular was his character that Hardin got his own show, Bronco (1958-1962), which became a global hit. After co-starring in a handful of fairly well-regarded B-pictures for Warner in the early 60s, Hardin thought he’d try his luck in Europe, where Bronco was also popular, and went on to star in a number of films, primarily in Spain and Italy, including Savage Pampas (1965) and Acquasanta Joe (1971). He had small roles in Hollywood films made in Europe, such as Battle of the Bulge (1965) and Billy Wilder’s Avanti! (1972), and starred in the horror movie Berserk (1967), opposite Joan Crawford, which was filmed in the UK. In 1969 he starred in the Australian TV show Riptide, which ran for one season. After his run-in with the law in Spain in 1974, Ty Hardin returned to the US, where he mainly played small roles in low-budget movies or had guest spots on TV. In 1981 he appeared in the low-budget fundamentalist Christian apocalypse film Image of the Beast, in which the mark of the beast has been digitized.

James Anderson is an actor who, in my opinion, should have done bigger things. Alabama-bred Anderson trained in method acting under Max Reinhart, and almost immediately got a contract when arriving in Hollywood in 1940. His grizzle features and rugged demeanor typecast him as an an outlaw gunslinger or henchman in westerns, the genre in which he spent most of his career. While he was steadily employed and in demand for mostly villainous or otherwise unsympathetic characters, his career never elevated above that of a minor part player or villain of the episode on TV. He seldom got a chance to show off his range. Probably his most substantional movie role that of the unsympathetic adventurer, who, along with five other lost souls, try to get by as the sole survivors of a nuclear holocaust in Arch Oboler’s interesting but flawed no-budget film Five (1953, review). He had a small role in Donovan’s Brain (1953, review), and appeared in I Married a Monster from Outer Space. His role in the latter film suggests at the character developing into a full fledged hero, but unfortunately he is killed off halfway through. But something in Anderson’s portrayal suggests he could have been an excellent anti-hero in the vein of Clint Eastwood or Charles Bronson had he been given the opportunity. His best remembered role is that of Bob Ewell in the classic courtroom drama To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), playing the father of the girl who claims to have been raped a black farmhand. His last film appearance was in the Dustin Hoffman classic Little Big Man (1970). Anderson suddenly died on set while filming the movie.

The rest of the cast is made up of seasoned character pros. Ken Lynch as the heroic doctor gets an unusually sympathetic role. Lynch was normally a staple in numerous police shows on TV, often playing grizzled, tough cops – an occupatuion that also spilled over to films from time to time. Occasionally he got to play other kinds of roles as well, for example in guest spots on shows like Star Trek and Battlestar Galactica. Maxie Rosenbloom was a character unto himself – one of the many poor kids who tried to punch themselves ahead in life in the boxing ring. Rosenbloom won a light heavyweight belt in 1930, and kept boxing until the mid-30s, when he turned his slugger fame into a movie career. A drinker, gambler and womanizer, he fit right in in Hollywood, and went on to portray a number of colourful minor characters in film and on TV up until the late 60s.

The film also features Bess Flowers, who appeared in over to 1 000 films or TV productions, and was known about Hollywood as ”Queen of the extras”. She appeared in five films that won an Academy Award for best picture, and worked with most of the top directors in town. Flowers also got her fair share of credited roles, often in comedies. She played Stan Laurel’s wife in We Faw Down (1928) and had a major role in the Three Stooges pic Mutts to You (1938). Despite her prolific career, she only appeared in a handful of sci-fi films: The Mad Doctor of Market Street (1942, review), The Mad Ghoul (1943, review), The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), The Maze (1953, review), I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), The Fly (1958, review), The Lost World (1960) and The Absent-Minded Professor (1961). She was active between 1922 and 1964.

Among the dinner guests at Bill’s and Marge’s wedding in I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) is also Harold Miller, who was an actor of some note in the silent era, for example, he played the titular lead in the over 3-hour-long James Fenimore Cooper adaptation Leatherstocking in 1924. In the sound era he was consigned to extra work and appeared in over 700 films or TV series. Another extra, Ron Nyman, may be recognised by Marilyn Monroe fans as the tattooed sailor in There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954).

Editor George Tomasini was Alfred Hitchcock’s favourite, and worked on such films as Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960) and The Birds (1963). He also edited I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) and George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960).

For more on special effects creators John P. Fulton and Charles Gemora, please follow the links.

Janne Wass

I Married a Monster from Outer Space. 1958, USA. Directed by Gene Fowler. Written by Louis Vittes. Starring: Gloria Talbott, Tom Tryon, Ken Lynch, Alan Dexter, Robert Ivers, Valerie Allen, James Anderson, John Eldredge, Jean Carson, Chuck Wassil, Peter Baldwin, Ty Hardin, Jack Orrison, Maxie Rosenbloom, Steve London. Ciinematography: Haskell Boggs. Editing: George Tomasini. Art direction: Henry Bumstead, Hal Pereira. Makeup: Wally Westmore, Charles Gemora. Visual effects: John P. Fulton. Produced by Gene Fowler for Paramount Pictures.

Leave a comment