Framed for murder, Carlos uses an invisibility potion in order to escape from prison and prove his innocense – before he goes insane. Competently made in the Mexi-Noir mold, this 1958 effort by Alfredo B. Crevenna is hampered by the fact that it is nearly a carbon copy of “The Invisible Man Returns”. 5/10

El hombre que logró ser invisible. 1958, Mexico. Directed by Alfredo B. Crevenna. Written by Alfredo Salazar, Julio Alejandro & Alfredo B. Crevenna. Starring: Arturo de Córdova, Ana Luisa Peluffo, Augusto Benedico, Raúl Meraz. Produced by Guillermo Calderon. IMDb: 5.2/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Carlos (Arturo de Córdova) is about to get married to Beatriz (Ana Luisa Peluffo), but the wedding plans are put on hold when he visits the warehouse where he works and hears gunshots from an office. One of the company’s managers has been shot to death, and Carlos sees a glimpse of a man exiting the room. When he hears someone approaching, he grabs the gun that the killer has left behind. In walks colleague José (Nestor de Barbosa) and a nightwatchman, and they promptly arrest Carlos for the murder. However, sure of his innocense, Carlos’ brother Luis (Augusto Benedico) thinks he may have a way of springing Carlos out of jail and give him a chance to prove his innocense: Luis, you see, is working on an invisibility formula.

By 1958 Mexican filmmakers had already dabbled a great deal with horror and science fiction, but The New Invisible Man, or El hombre que logró ser invisible was the country’s first stab at emulating the Invisible Man films of Universal – inspired by the novel by H.G. Wells. The New Invisible Man is something of a novelty in 50s Mexican science fiction as it is neither a comedy, a lucha libre film nor does it draw its inspiration from murky monster movies. It is is much a whodunnit thriller as a science fiction outing, played straight and directed by Alfredo B. Crevenna with a modicum of style and restraint.

After several trials and errors involving experinents with monkeys and rabbits, the formula for an invisibility potion keeps eluding Luis. And time is running out since Carlos is fast losing faith and goes on a hunger strike. Finally, when hope seems lost, Luis accidentally spills two of his components on the floor, making a cockroach invisible. With Carlos moved to the infirmary, Luis is able to see him in his capacity as a medical doctor, and secretly injects him with his new serum. It works: Carlos becomes invisible and escapes.

The police, led by Comandante Flores (Raúl Meraz) set out to catch Carlos – not knowing he is invisible – and tail Beatriz. After some games of cat and mouse, she is able to pick up Carlos in her car and take him home to her place, where he starts formulating a plan to prove his innocense. This takes him back to the office/warehouse where he works. Thanks to his invisibility he is able to observe José conducting drug business in the warehouse, and kill a security guard who catches him in the act (José Muñoz).

Meanwhile the police are slowly putting two and two together, from reports of some invisible menace prowling the streets and attacking thugs, and Carlos’ mysterious escape. Despite the fantastic notion, Comandante Flores is convinced that Carlos has somehow turned himself invisible. The police track Carlos to Luis’ house, where they form human chains and flood the house with gas in order to catch him. However, Carlos knocks out one of the police officers, puts on his uniform and gas mask and escapes.

When all seems to be going to plan, Luis makes a disturbing discovery while watching his test animals: the drug will lead Carlos to become insane if they don’t find an antidote soon. Luis is right: Carlos soon declares that he no longer has any interest in bringing the real killer to justice – instead he plans on becoming the ruler of the world. Nevertheless, he confronts José and forces him to sign a confession that he is really the murderer. But after Carlos leaves, José pays a visit to the boss of his workplace, Don Ramon (José Mondragón), who also happens to be Beatriz’s father. Here, he forces Don Ramon to sign a confession of his own – it turns out that José has been conducting his drug business in league with Don Ramon. But Don Ramon knocks out José and beats the living daylights out of him. Unbeknownst to Don Ramon, however, Carlos has followed José, and now Carlos declares that he is “a messenger from the highest judge” and makes Don Ramon bow before his authority. After Carlos leaves, José musters the last of his powers and shoots Don Ramon, before himself succumbing to his injuries. Thus, the movie neatly gives Carlos his revenge without having him kill anyone.

But now Carlos is in full Claude Rains mode and tells Luis and Beatriz that he is going to poison the city’s water supply, killing everyone who drinks it. This leads us to a final showdown at the city’s dam – and Luis is fighting against the clock in order to prevent an antidote …

Background & Analysis

Mexico was the 4th biggest producer of science fiction movies in the 50s, after the US, UK and Japan. The country had dabbled in the genre since the 30s, primarily inspired by Universal’s monster and horror pictures. By the late 50s, Mexico’s film industry, which counts its golden age between 1936 and 1956, was dwindling. Already in the early 50s Mexican filmgoers started feeling that the western or charro movies, melodramas and comedies that dominated the country’s movie scene were getting formulaic. Luis Buñuel injected some new energy into the field in the 50s, but the overall trajectory of Mexican cinema was downwards. Something new was needed, and during the 50s producers, writers and directors increasingly turned to “new” genres and started emulating the Hollywood films that they had previously tried to distance themselves from. Science fiction and horror had already proven popular in the country, and Universal’s old horror movies were still audience favourites.

One of the most popular new tropes was the Mexican show wrestler, the luchador. With the rise of superstar Santo, lucha libre became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the country, and soon the wrestlers took their place on the movie screen as well. However, the luchador genre as we are familiar with it today – featuring luchadors as superheroes – didn’t really come together until the early 60s, when Santo finally agreed to appear in a movie.

Horror and science fiction were genres that increased in popularity during the 50s. Stylistically they were diverse. From the murky mad scientist yarns like El monstruo resucitado (1953, review), early luchador outings like La sombra vengadora (1954, review), and monster films like The Body Snatcher (1957, review) and the Aztec Mummy trilogy (1958, review) to comedies and spoofs like Los platillos voladores (1956, review) and El castillo de los monstruos (1958, review), Mexican filmmakers were enthusiastically experimenting and trying to find their form.

These films were often, if not always, made on small budgets and had very limited resources for special or visual effects. Effects tended to be in-camera, and mostly consisted of monster makeup. For producer Guillermo Calderón and director Alfredo B. Crevenna to tackle an invisible man film was on the one hand obviuous, since the Mexican horror films had already been through the Universal catalogue of Draculas, Frankensteins, wolfmen and mummies. On the other hand it was a hugely ambitious undertaking, considering the requirements put on the special and visual effects. The effects team was headed by director or photography Raúl Martínez Solares, mechanical effects supervisor León Ortega and effects technician Jorge Benavides.

One of the driving forces behing the rise of the Mexican SF and horror movies – and the luchador films – was producer Guillermo Calderón, who had reaped much success with the so-called Rumberas films in the 40s and early 50s. In 1958 alone he produced both the Aztec Mummy trilogy and The New Invisible Man – both based on story treatments by Alfredo Salazar. For his director he chose the merited Alfredo B. Crevenna. Neither Calderón nor Crevenna had much experience with either horror or science fiction – they both made their first horror movies in 1957, and their first SF films in 1958. But Calderón might have chosen Crevenna partly for his strong background in film chemistry – Crevenna was well versed in the process of post-production visual effects, having studied chemistry at Oxford and collaborated with Agfa researchers on things like colour photography and syncronised sound. Writer Alfredo Salazar also had very little experience with the genres. He had primarily been associated with comedy, but was probably inspired to try his hand at horror and SF after his brother Abel Salazar made the hugely popular Dracula reimagination El Vampiro in 1957.

Salazar is credited for story, Julio Alejandro for adaptation and Crevenna for screenplay – Alejandro had written the screenplay for Crevenna’s previous horror movie Yambao (1957). Those familiar with Universal’s Invisible Man franchise will probably recognise that El hombre que logró ser invisible (“The Man Who Made Himself Invisible”) is basically a retread of Joe May’s first sequel The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review). In that film we follow a man who is falsely accused of murder, whose friend helps him inject an invisibility serum and spring him from prison. He sets out to prove his innocense with the help of his fiancée, but is hunted down by the police who traps him in a house with human links and flood it with gas. Here he steals a uniform and escapes. However, the serum is slowly turning him insane, and it all comes down to a dramatic showdown at a coal mine, and his friend must chase the clock in order to find an antidote.

When hammering out the main plot points, there are few differences between The Invisible Man Returns and El hombre que logró ser invisible. Still, Crevenna & Co add just enough local flavour and additions as not to make their film feel like a complete ripoff. For one thing, the Mexican film is urban, while Universal’s played out at a faux British small town, giving them very different vibes. Salazar and Crevenna add the drug dealing and mobster subplot as a thread to the film, and while it isn’t really essential for the plot, it does add a new dimension to May’s film. Another major change is that unlike Vincent Price’s character in the US film, Carlos actually does go completely mad in the end – echoing Rains’ character in The Invisible Man (1933, review). And here – unlike in any of Universal’s movies, the invisible man actually gets as far as trying to implement his designs at world domination. Rains only got as far as “a few murders” before being gunned down in the snow.

As for themes, the filmmakers probably didn’t intend this as any sort of message movie or a film for serious ruminations. In the background there’s the old “things that man shouldn’t dabble in” trope, warning of the dangers of scientific hubris. Because of the premise of a man trying to prove his innocense (and the fact that it his brother who concocts the serum), this theme feels more like a trope carried through from Hollywood than like something than anyone put any considerable amount of thought into. El hombre que logró ser invisible has a stronger emphasis on religion than its US counterpart, but, again, this is more a reflection of Mexican culture with its Catholisism deeply embedded in society, rather than an effort to say anything meaningful.

A bit of a spoiler here, so skip the next paragraph if don’t want to know how the film ends. In the paragraph I’m writing about the fact that the conclusion of the movie is somewhat confounding.

*** SPOILER ***

As stated above, the ending of El hombre que logró ser invisible does leave one confused about what the moral conclusion is supposed to be. In the finale, Luis tries to stop Carlos from poisining the water supply, only to have Carlos shoot him dead. The police then shoot and wound Carlos, who makes a full recovery and becomes visible after receiving the antidote that Luis has concocted. The final scene shows Carlos and Beatriz happy together, on their way to get married. No thought is given to Luis, the real hero of the film, who not only sacrificed himself to save the city but who is also the only reason that Carlos not a) behind bars accused of murder or b) invisible and insane or c) shot dead by the police. This omission is only exaggerated by the fact that Luis is by far the most sympathetic character in the movie. While it is certainly true that Carlos can’t really be blamed for his actions, such as killing Luis, as he was under the influence of the drug, it also feels weird that Luis’ death is sweeped under the carpet without as much as a mention. I suppose the filmmakers wanted a happy ending – but it’s literally only three minutes between Luis getting shot and the happy couple heading off into the sunset. As a viewer, I’d rather have seen Luis survive than Carlos – who gets off scot-free.

*** END OF SPOILER ***

It’s all highly formulaic, and the plot can be understood almost perfectly even by watching the film in Spanish without subtitles. I saw the movie both in Spanish (with auto subs) and dubbed in English. The Mexican version in 96 minutes long, and the US version 10 minutes shorter. The plot is exactly the same in both movies. The only thing cut, as far as I could tell, in the US version was a sort of intro with Carlos and Beatriz planning their new home at a construction site. It’s a pretty fun and sweet sequence, which presents the couple and helps us invest in them. But it is also too long, and the omission of it in the US cut doesn’t really hurt the film.

The special effects of The New Invisible Man rely on a combination of wirework and travelling mattes, as they did in Universal’s movies. They are, on the whole, quite competently achieved, even if there is nothing on screen as ambitious as some of Universal’s visual effects wizard John Fulton’s tricks in the original films. For example, the few scenes in which the invisible man is undressing are rather crude and don’t even come close to Fulton’s legendary mirror scene in the 1933 film (even if a mirror shot does appear in the film). We get all the classics: footsteps appearing on the ground, indents in cushions, books being turned by invisible hands, doors opening and closing, objects levitating and matches and cigarettes floating in thin air. There’s a few shots that seem to be utilising the technique of filming the actor in a black suit against a black background. They are few and far between, but actually quite well executed. One effective scene is one that is lifted from Invisible Agent (1942, review), in which Jon Hall applies face cream in order to become visible. Here Carlos applies makeup to his face – the matte lines are a bit thick, but nonetheless it is a pretty nifty moment. Unfortunately the film doesn’t carry it through: in the next scene, we see actor Arturo de Córdova filmed without the thick makeup on his face – just with his natural face and black glasses, which shatters the illusion.

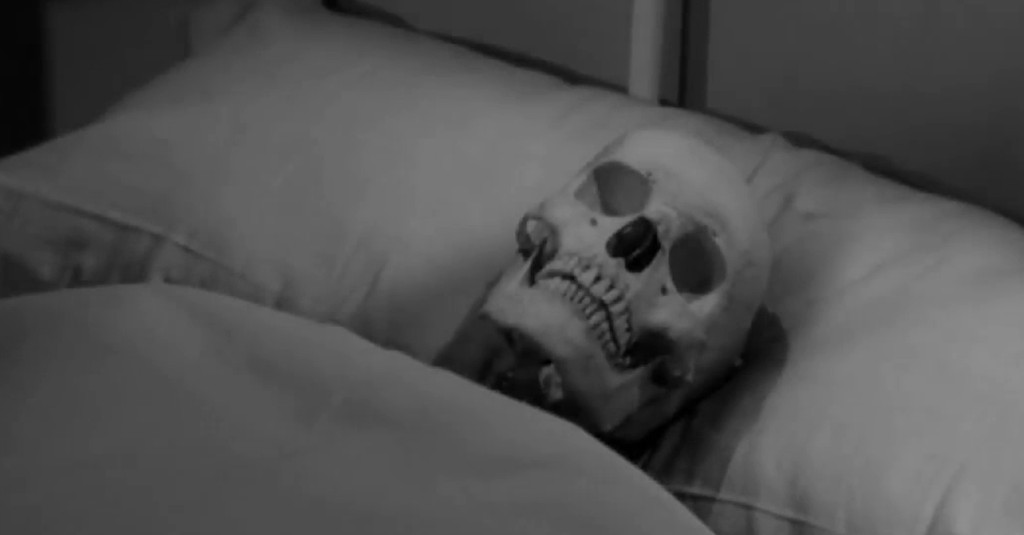

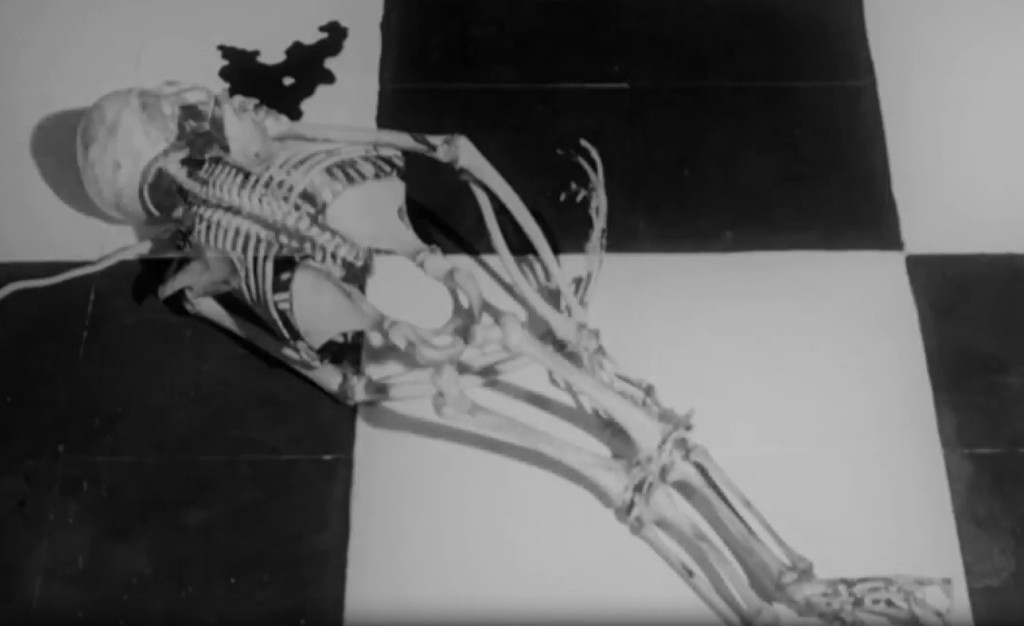

During most of the film, Carlos’ invisibility is illustrated only by people interacting with thin air and by a number of rather simple wire tricks. Other special effects, such as Luis’ experiments with animals are not bad at all – achived with simple double exposure cross-fades, showing the skeleton of said animals in the intermittent stages of the process. Augusto Benedico’s convincing interactions with the animals and props does much to sell the illusions. In the end of the film, cinematographer Raúl Martínez Solares copies the ending of The Invisible Man Returns, having his protagonist gradually coming back into view, starting with a skeleton – however, it is not as accomplished a shot as that in May’s movie.

Some online commentators have complained that Martínez & Co have not improved on Fulton’s special effects, even though the Mexican film was made 25 years later than the original Universal movie. In part, this criticism is valid, if one views it from the point of view of the motivation of making a new Invisible Man film. The New Invisible Man doesn’t bring anything new to the table story-wise: as mentioned, it is basically a rehash of The Invisible Man Returns. As such, the special effects are the draw. And the special effects offer no new wow-moments – there’s nothing here to see that could not be seen in the original films. Thus, there’s nothing either in the story nor in the effects that would merit another invisible man version. So, it is quite legitimate to ask whether we really needed another Invisible Man film.

On the other hand, the accusation that El hombre que logró ser invisible doesn’t further the development of the special effects partly reveals a misunderstanding of the evolution of visual effects – a misunderstanding that is understandable considering the giant leaps in computer graphics (and AI-generated imagery) in the past 30 years. The fact is that the single greatest evolution in visual effects between 1933 and 1958 was the blue screen – which made the sort of travelling matte work used in black-and-white films for decades available for colour films. For black-and-white films the toolbox for creating visual effects was the same in 1958 that it was in 1933: stop-motion, cross-fades, rear projection, “black screen photography”, mattes, mirror shots, etc. Most of these had been around since the birth of movies; the thing that created a leap in visual effects in the 30s was the invention of the optical printer, which made it possible to use different strips of film for the same effects shot. This development greatly increased the scope of work that could be done for a single shot without risking misalignment, over- or underesposure or degradation of the film strip. This technogy didn’t change in any essential manner between 1933 and 1958. Certainly movie effects and cinematography saw developments during these years: practices and instruments were refined, film stocks and lighting were improved upon, etc, but John Fulton had pretty much exhausted the possibilities of the medium in the 1933 film, and expecting invisibility effects that would have presented anything radically new in 1958 is just wishful thinking.

So: while the question whether we needed another rehash of Universal’s Invisible Man films is valid, one can hardly demand that every film put into production has to advance the art of filmmaking. Furthermore, the fact that El hombre que logró ser invisible was produced in Mexico and not in Hollywood, puts it in a whole other category. The movie probably represented the pinnacle of Mexican special effects at the time, with a fairly large amount of screentime filled with effects of one sort or the other. The effects may not break new ground, but most of them are relatively well executed, and surely provided the effects team – both practical and visual – with a possibility to hone their craft further than usual.

Of course, none of these factors prevent the screenwriters from showing a hint of originality in their work. If the idea was to create Mexico’s own version of The Invisible Man, it feels like an odd choice to rehash The Invisible Man Returns. With the exception of the drug cartel subplot and the ending by the dam, the movie follows its inspiration beat for beat, as far as recreating certain setpieces almost shot for shot. The drug subplot has nothing to do with the central premise of the film and adds nothing of particular interest to the story. Thus far, Mexican filmmakers had been apt at putting their own spin on Hollywood tropes, sometimes for better, mostly for worse, but at least the Mexican versions of American horror films had distinctly unique flavour. Here it feels as if the screenwriters just didn’t bother with coming up with anything original, but simply slapped The Invisible Man Returns into a Mexican setting.

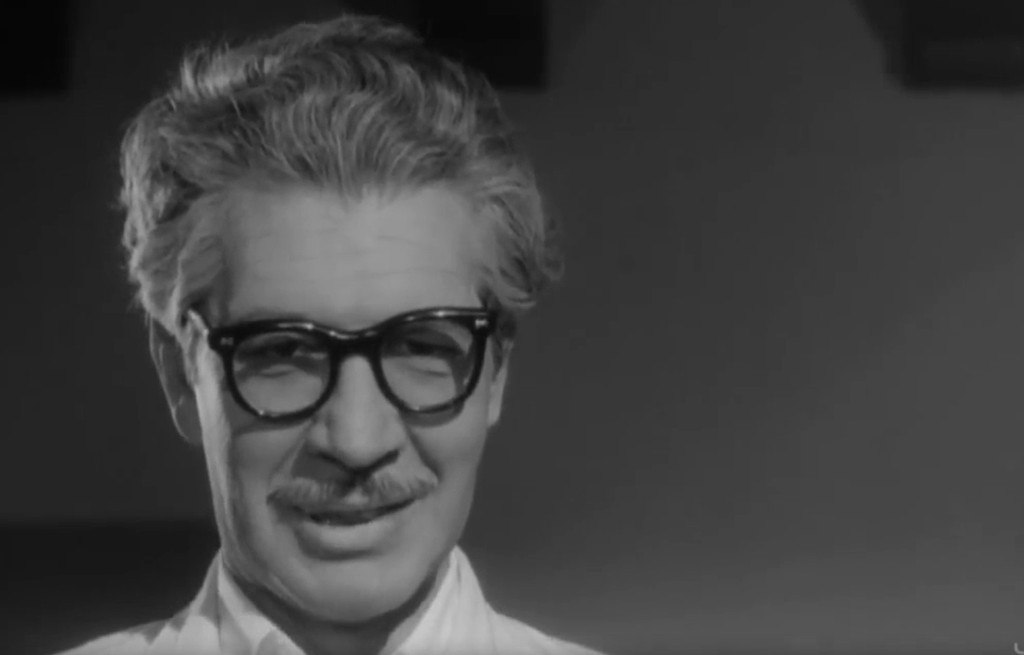

That said, the direction by Alfredo B. Crevenna is competent, drawing inspiration from film noir rather than from horror movies, much like The Invisible Man Returns. There’s a few standout moments, such as a wide shot of a large room when the police are confronting the invisible man, about to smoke him out. There’s some inspiration in Comandante Flores swinging a bull whip around the room, catching the invisible man by the neck – a well executed effect, as well. There’s none of the low-budget creakiness that marred, for example, the Aztec Mummy trilogy with its unintended comedy. As a thriller, the film may be formulaic and predictable, but it is competently made. The acting is likewise competent (almost) across the board. The standout is Augusto Benedico as Carlos’ scientist brother, who has a magnetic charisma and is able to credibility to the outlandish science. On the other side of the spectrum is Ana Luisa Peluffo in the female lead. A seasoned leading lady, she nevertheless comes off as “acting” in the scenes where she is supposed to be distraught and forlorn, which every other scene she is in. There’s never a sense of real emotion. Artúro de Cordova is serivceable in the lead, but never gets across the same menace or authority as a Claude Rains or Vincent Price. In fact, I think the actor doing the English dub is actually better.

All in all, considering the limited resources, The New Invisible Man is a competently made science fiction thriller, even if the science fiction element doesn’t really have anything with the thriller element to do (this was also a flaw in The Invisible Man Returns). It takes its subject-matter seriously and feels like a film geared toward an adult audience. The special effects are good enough not to take you out of the story. The acting is, for the most part, solid, even in the dubbed version. Unfortunately it is also predictable and programmatic – after watching the first 15 minutes you can pinpoint the plot with considerable accuracy. Not least because this is a blatant ripoff of a movie made 25 years earlier. It’s a film well worth watching for anyone wanting to broaden their horizons beyond Hollywood’s 50s science fiction movies, and it is an entertaining enough whodunnit. I don’t usually condone watching dubbed movies but in this case the dubbed version will suffice just as well as the original. Anyone looking for the sort of unhinged madness offered up by many other Mexican horror and SF films of the era – usually involving luchadors – will be disappointed, as El hombre que logró ser invisible represents an unusually restrained approach.

Reception & Legacy

El hombre que logró ser invisible premiered in Mexico in December, 1958, and the English dub, as The New Invisible Man, was first shown on US TV some time in the mid-60s. It has sometimes been referred to as The Invisible Man in Mexico or H.G. Wells’ The New Invisible Man, a misnomer indeed as this film has virtually no similarities with Wells’ novel.

Despite a thorough archive search, I have found no contemporary reviews of this film, which tends to be the case with Mexican B-movies of the 50s. In his book Keep Watching the Skies (2009) Bill Warren opines that the film has “uneven special effects, but it’s passable”. In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies (1984), Phil Hardy writes a tongue-in-cheek review of the movie, but it is clear from his plot synopsis, full of errors, that this is yet another one of the many reviews in the Encyclopedia that has either been cobbled together from second-hand sources or by someone who has only vague memories of having seen the film many years ago.

Modern critics tend to highlight the blatant similarities between El hombre que logró ser invisible and The Invisible Man Returns. José Luis Salvador Estebenez at La Abadia de Berzano calls the film “nothing more than an uncredited remake of The Invisible Man Returns“, while Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings says that it “doesn’t really add anything new to the idea”.

Most crtitics see the movie as an interesting but middling curio, although some on the Mexican side of the border have a more positive take. An unnamed reviewer at the film portal Corre Camara calls it “a relevant title, worth rediscovering as the most accomplished science fiction film by Alfredo B. Crevenna“. The afore-mentioned José Luis Salvador Estebenez at La Abadia de Berzano finds it “a very enjoyable and rewarding film, which, if that weren’t enough, benefits from competent acting work led by an actor of the caliber of Arturo de Córdova. Its main weakness lies in a certain narrative gap caused by its lengthy resolution”.

US critics are, on the whole, more reserved. Mark David Welsh says: “The film is well acted, with some effort made to display credible emotional crises, as well as the more outlandish details of the tale. The real problem here is that it’s nothing new and, without a fresh take on the idea, it remains a resolutely average way to spend 90 minutes, even though it’s efficiently delivered by director Alfredo B Crevenna.” Dave Sindelar writes: “Unfortunately, this is one of the lesser entries in the field [of 50s and 60s Mexican horror]. It borrows little from Wells and is hardly new, being essentially a remake of one of the Universal invisible man sequels. This one doesn’t really add anything new to the idea, and is somewhat dull.”

The New Inbisible Man did not start at trend of invisibility films in Mexico. The only other two Mexican science fiction films I can find in which invisibility is a central part of the premise are the slapstick comedy Los Invisibles (1963) and the luchador film El asesino invisible (1965), which Mark David Welsh calls ” little more than a retread of the far superior El hombre que logró ser invisible“.

Cast & Crew

Alfredo B. Crevenna was one of the most successful directors during the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, specialising in melodramas. His latter years in the industry were spent primarily making low-budget productions in various genres. He was active in the film industry from the mid-30s until his death in 1996, directed over 150 movies and wrote over 40.

Crevenna was born Alfredo Bolongaro Crevenna in Germany in 1914, and belonged to the originally Italo-Swiss noble merchant family Bolongaro. As a young man he rejected his nobility and chose to go by the name B. Crevenna, rather than by his noble family name. Although he showed an interest in the movies from an early age, he studied chemistry and physics at Oxford, which led him to work for a while for the German film stock producer Agfa, where he researched colour film and synchronous sound. He worked in the German film industry for a few years in different capacities and made his directorial debut in 1936, but moved to the USA either in 1938 with the rise of fascism in Europe. Here sources diverge. According to some sources he worked for a while for Warner Bros. in Los Angeles, but in an interview with film historian Rogelio Agrasánchez, Jr, Crevenna claims that he moved to New York, where he tried in vain to get a work permit for three months before moving to Mexico City at the suggestion of a friend.

Arriving in in Mexico in 1938 without speaking a word of Spanish, Crevenna was surprised that his first job in the Mexican film industry was to rewrite the script for La noche de los mayas (1939). According to the Agrasánchez interview, he went to the bookstore and bought and English-Spanish dictionary (they didn’t have a German-Spanish one), translated the script and made several changes, which were looked approvingly on by the studio. Thus started an extremely successful 55-year Mexican movie career.

Crevenna started his Mexican career as a screenwriter, but made his first Mexican film as a director in 1945, Adán, Eva y el diablo, a comedy. However, the peak of his career stretched from 1950 to 1956, when he directed and co-wrote half a dozen hugely successful melodramas, which Eric Lavallée at IonCinema writes “played like more robust versions of American ‘women’s pictures’ mixed with questionable exploitation elements”. Today the most famous of these is probably Muchachas in Uniforme (1951), which is widely regarded as the first Mexican picture to explore lesbian themes. Crevenna’s movies in this period were both commercial and critical successes, culminating with the colour movie Talpa (1956), which earned a whopping 11 Ariel Award nominations, including best picture, and won four awards. The movie also earned Crevenna a Palm d’Or nomination at the Cannes Film Festival. Several of his movies starred the real-life superstar couple Marga López and Arturo de Cordova – the star of The New Invisible Man. Especially López was a favourite of Crevenna’s and she has later said that Crevenna gave her the best roles of her career.

As stated above, by the end of the 50s, the popularity of the sort of melodrama that Crevenna had specialised in was waning, and the director quickly sought new avenues: horror (sort of) with the voodoo soap opera Yambaó/Cry of the Bewitched (1957) and science fiction with The New Invisible Man (1958). By the 60s, the large majority of his output would be considered B-movies, often genre pictures shot on a fairly meagre budget. In the above-mentioned interview, Crevenna says that he devised system that allowed him to shoot four films back-to-back over eight weeks, which made him very popular with Mexican film studios. Today Crevenna is probably best known internationally for his horror and science fiction output from the 60s, 70s and 80s. He made several luchador pictures, including at least half a dozen with Santo, and a whole number of campy horror movies. IMDb classifies 14 of his films as science fiction. These include titles like Aventura al centro de la tierra 1965), Gigantes planetarios (1966), El planeta de las mujeres invasoras (1966), Santo el Enmascarado de Plata vs ‘La invasión de los marcianos’ (1967), Pasaporte a la muerte (1968), El puño de la muerte (1982) and La furia de los karatecas (1982). While Crevenna was repeatedly nominated for best direction and best picture both i Mexico and at prestige film festivals abroad in the 50s, he never won a major award. The few biographical notes and quotes I can find about Crevenna paint a picture of a pleasant man who didn’t take himself or his art too seriously.

Information on story writer Alfredo Salazar online is sparse, apart from what can be gleaned from IMB. José Alfredo Salazar García was born in 1922 and was the brother of star actor Abel Salazar, who went from melodrama heartthrob in the late 40s and early 50s to horror movie icon in the late 60s and 70s. Alfredo Salazar emerged in the late 40s as a story and screenwriter, primarily for comedies. According to one source, he wanted to break out of this mold, and probably saw his chance in 1957 when his brother Abel produced, co-wrote and directed the Dracula variation El Vampiro, which became a sensational hit and helped pave the way for a new wave of Mexican horror films. The next year, Salazar teamed up with his frequent collaborator, producer Guillermo Calderón, and together they made the so-called Aztec Mummy trilogy (1958, review). While the trilogy wins no awards for quality, it has remained a cult favourite and has been the inspiration for numerous later films on the theme.

What emerges from Salazar’s credit sheet and from the few adademic mentions available is a picture of a “working writer” rather than an auteur, often credited either as story originator, a script doctor or as part of a team of writers. Film scholars tend to highlight his role in the maintenance of the cycles of mummies, luchadores, and low-budget horror and science-fiction, especially emphasising his role in adaptation, sequel-making, and trope recycling. In an interview cited by Monica Garcia Ramirez in Diccionare de Directores del Cinema Mexicano, Salazar described himself as a “one hundred percent commercial” writer and producer, explaining that it was popular entertainment that was primarily in demand and kept him working. His career stretched from 1948 to 1993, after which he retired. In the 60s and 70s he also took in directing and producing. Among his best known work are, apart from the Aztec Mummy trilogy, The Vampire’s Coffin (1958), The Batwoman (1968), Night of the Bloody Apes (1969), Santo in the Treasue of Dracula (1969) and Darker Than Night (1975). His science fiction output also included titles like The New Invisible Man (1958), Doctor of Doom (1963), The Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Mummy (1964), La isla de los dinosaurios (1967) and Santo & Blue Demon vs. Doctor Frankenstein (1974).

Producer Guillermo Calderón, along with brother Pedro, had behind him a distinguished career as one of the principle drivers of the so-called Rumberas film in the 50s. The Rumberas was a hugely popular genre of often urban melodrama infused with latin rythms, mostly centering around lower-class women such as prostitutes, barmaids and club singers and dancers. While it can be argued that the first examples of the Rumberas film emerged as early as the late 30s, it wasn’t until the 50s that the genre’s popularity exploded, partly thanks to Calderón’s films The Adventuress (1950), Victims of Sin (1950) and Sensualidad (1951).

By the mid-50s, the Rumberas film was losing popularity, partly because the genre had exhausted itself, and partly because of a new conservative government, which cracked down not only on the “immorality” of the Rumberas film, but also on the liberal urban nightlife which fed the genre. For Calderón, the decline of the Rumberas film was no insurmountable obstacle – he had been producing films in numerous genres since the mid-40s, and continued making crime films, urban melodramas, musicals, comedies and westerns. With a keen eye on what was happening in Hollywood, Calderón didn’t take long to latch on to what companies like Allied Artists and American International Pictures were churning out on minuscule budgets with reasonable success. With films like Los chiflados del rock and roll (1957) and Peligros de juventud (1960), Calderón tried to cater to a new, younger audience with a changing taste in culture. But he also ventured into the horror and science fiction genres which in Mexico at the time were becoming increasingly linked to the quickly emerging new craze: the lucha libre film.

For more on the birth of the lucha libre film, see my review of El enmascarado de plata (1954). The late 50s was the period when the luchador movie was starting to emerge as a sort of domestic superhero alternative in Mexico. The genre really exploded in 1961 when the superstar of Mexico’s lucha libre rings, Santo, decided, after many years’ hesitation, to lend his face to the screen. Around 150 luchador films were produced during the genre’s heyday in the 60s and 70s, and some of the most legendary were the products of Guillermo Calderón and Alfredo Salazar. It was these two who introduced the infamous “wrestling women” in movies like Doctor of Doom (1963), The Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Mummy (1964), The Panther Women (1967) and Wrestling Women vs. the Murderous Robot (1969). Likewise, it was Calderón and Salazar who wrote and produced the hilarious cult classic The Batwoman (1968), in which a very sexed-up version of Bob Kane’s iconic comic book character meets the lucha libre world. Calderón struck gold when he produced over half a dozen Santo movies, several of which are among the most regarded of the wrestling star’s movie career – many of these were also written by Salazar. During his “golden years” in the horror and lucha libre genres, he also produced The New Invisible Man (1958), the oddball Christmas movie Santa Claus (1959), in which Merlin and old Nick thwart the devil’s plans to ruin Christmas, the lost world film La isla de los dinosaurios (1967) and the infamous Night of the Bloody Apes (1969), which in its export version included a multitude of bare boobs, footage of real open heart surgery and bad gore effects. With the decline of the luchador genre and the Mexican horror genre, Calderón once again landed squarely on his feet, and began producing rather innocent sex comedies and melodramas with titles like Juventud desnuda (1971), Bikinis y rock (1972), Bellas de noche (1975) and Las modelos de desnudos (1983). He retired in 1994, and passed away in 2018.

Lead actor Arturo de Cordova was one of the few superstar names of Mexican cinema that appeared in the horror/science fiction films produced from the 50s onward – he probably agreed to star in The New Invisible Man thanks to his friendship with director Crevenna. Cordova could be the subject of a long bio, but since The New Invisible Man is his only science fiction credit, he is not particularly relevant for this site. Suffice to say, he won three Ariel Awards for best actor, and was nominated for three more. During the 40s Cordova was also a familiar face for Hollywood audiences. He is perhaps best known for his substantial role in the Gary Cooper/Ingrid Bergman vehicle For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), but he also played romantic leads in almost a dozen B-movies, including Frenchman’s Creek (1944), Incendiary Blonde (1945), New Orleans (1947) and Adventures of Casanova (1948).

Ana Luisa Peluffo, who plays the female lead in The New Invisible Man, made her most lasting impression on Mexican cinema by taking off her clothes. But before she rose to fame, she was an artistically inclined young lady who practiced both art and sports. One of her interests was water ballet, and she was captain of her water ballet team. This was how she came to appear as one of the titular “Aquitarians” in the 1948 movie Tarzan and the Mermaids, at the age of 19. A few incredited minor parts in Mexican films followed, but it wasn’t until 1954 that she had her first credited movie role, in a small part in Alfredo B. Crevenna’s Orquídeas para mi esposa. In only her second credited role, in Miguel Delgado’s sensual drama La fuerza del deseo, she became a nationwide sensation after what is generally credited as the first nude scene in Mexican cinema.

While her status as a sex symbol remained, Peluffo tried to distance herself from her image as a seductress by appearing in a variety of roles in melodramas and comedies, with her clothes firmly on. However, as the years drew on, she found herself primarily employed in B-movies, and eventually had to fall back on her reputation and start taking her clothes off again. More than anything, however, her latter career is noteworthy for the sheer number of movies she appeared in. From the 70s onward, Peluffo was one of the most prolific actresses in Mexican cinema, and although not all of the films she appeared in were of the highest quality, there is the occasional gem in there. From the late 80s onward she also started appearing in recurring roles in a number of soap operas on TV. By the time she graced the big screen for the last time in 2012, she had appeared in over 200 films. Her SF material includes The New Invisible Man (1958), Conquistador de la luna (1960),

Pasaporte a la muerte (1968) and Mágico, el enviado de los dioses (1990). As of September, 2025, Peluffo is still among us at the enviable age of 95.

Augusto Benedico, who plays the invisible man’s scientist brother in The New Invisible Man (1958), was an in-demand character actor. With his deep voice, and thoughtful, intelligent air, he often played scientists, authorities and father figures. Cineastes might recognise him from his major role in Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962), whole friends of more schlocky fare may have seen him in another film made that same year, Santo vs. the Vampire Women.

Most of the other actors in the movie were similarly seasoned character actors, all of who made over hundred or several hundred movies. Worthy of mention is Jorge Mondragón, who is known in Mexico for his strong union activism for actors rights. Mondragón appeared in minor roles in a number of science fiction and lucha libre films – including one of Mexico’s very first SF movies, Los muertos hablan (1935, review) and the terrible Buster Keaton vehicle Boom in the Moon (1946, review). He also had roles in The New Invisible Man (1958), Doctor of Doom (1963), Santo in the Wax Museum (1963), The Panther Women (1967) and Santo and Blue Demon vs. Dr. Frankenstein (1974). Manuel Dondé, in a minor role in The New Invisible Man, won three Ariel Awards for an actor in i minor role. He is best known internationally for his surprisingly substantial role in The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948) as the villain El Jefe trying to get his hands on the gold that Humphrey Bogart and the other prospectors are hunting for.

The number of Ariel Award wins and nominations racked up by the team behind the camera says something the quality of the crew behind The New Invisible Man. Cinematographer Raúl Martínez Solares won an Arien Award for best cinematography for Alfredo B. Crevenna’s Yambaó, and was nominated for four more. Composer Antonio Díaz Conde also won an Ariel, and was nominated several times. Editor Jorge Bustos won three Ariels and production designer Javier Torres Torija was nominated for four.

Janne Wass

El hombre que logró ser invisible. 1958, Mexico. Directed by Alfredo B. Crevenna. Written by Alfredo Salazar, Julio Alejandro & Alfredo B. Crevenna. Starring: Arturo de Córdova, Ana Luisa Peluffo, Augusto Benedico, Raúl Meraz, Nestor de Barbosa, Jorge Mondragón, Roberto G. Rivera, José Muñoz, Manuel Dondé. Cinematography: Raúl Martínez Solares. Music: Antonio Díaz Conde. Editing: Jorge Bustos. Production design: Javier Torres Torija. Makeup: Felisa Ladrón de Guevara. Sound editor: Abraham Cruz. Special effects: León Ortega. Visual effects: Raúl Martínez Solares, Jorge Benavides. Produced by Guillermo Calderon for Cinematografica Calderon & Azteca Films.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply