Alien John Carradine lands his space ship in Bronson Canyon and causes a war of words between a military man and a scientist about what to do with the visitor. A cheaply produced 1959 programmer, this talky cold war parable has a baffling script, but is mostly harmless. 4/10

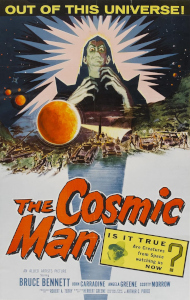

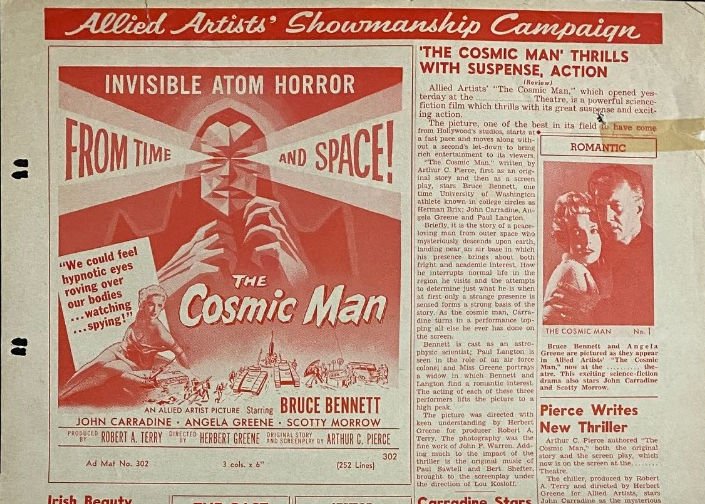

The Cosmic Man, 1959, USA. Directed by Herbert Greene. Written by Arthur C. Pierce. Starring: John Carradine, Bruce Bennett, Angela Greene, Paul Langton, Scotty Morrow. Produced by Robert Terry. IMDb: 4.8/10. Lettterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A

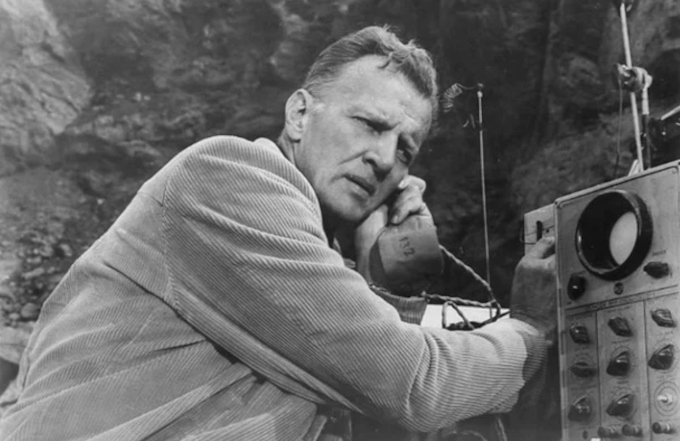

A mysterious spherical spaceship lands in Bronson Canyon and has the military and the scientists up in arms. Dr. Carl Sorenson (former Tarzan Bruce Bennett/Herman Brix) wants to study it and treat any visitor as a guest, while Col. Matthews (Paul Langton) wants to break into the sphere and steal its secrets for the war industry. Dr. Sorenson draws the longer straw, as the the sphere turns out to be impenetrable. Meanwhile, a strange man in a fedora and weird glasses (John Carradine) takes up lodging in a nearby inn run by the young widow Kathy (Angela Greene), who takes care of her polio-stricken, wheelchair-bound son Ken (Scotty Morrow). But strange things are afoot, as people keep seeing a shadowy figure around the nearby smalltown.

The Cosmic Man is one of the many 50s films inspired by The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), but was probably made on a tenth of that film’s budget. It has remained an obscure curio, best remembered for the brief appearance of first-billed John Carradine. Filled with B-movie stock actors, it was directed by the inexperienced Herbert Greene and independently produced for United Artists by first-time producer Robert Terry.

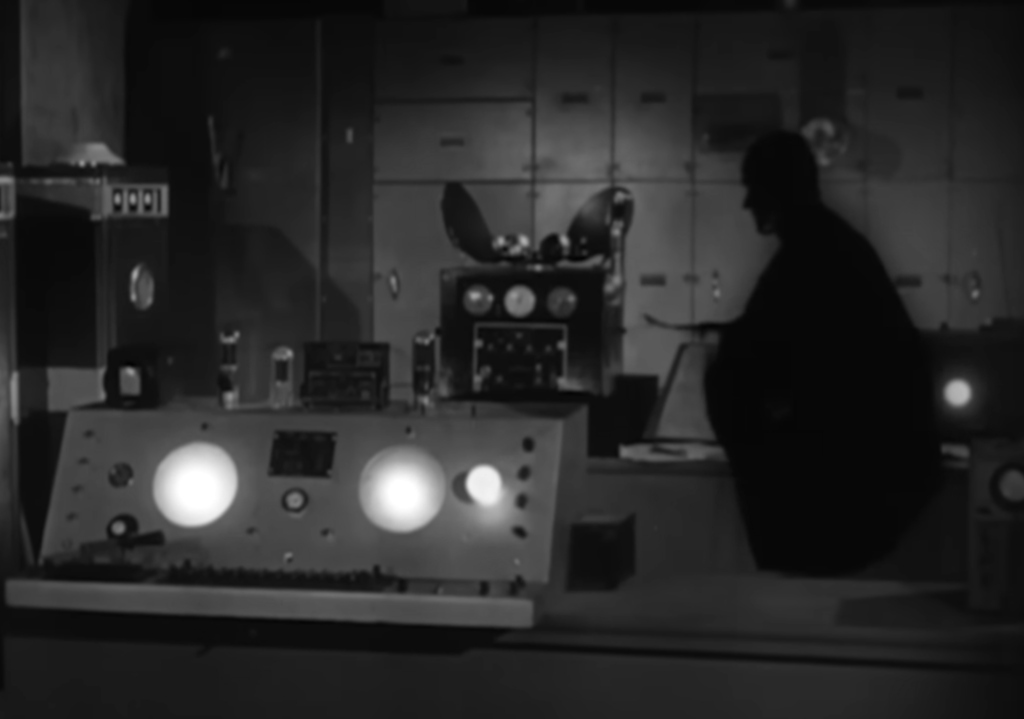

During the night the shadowy, partly translucent Cosmic Man secretly visits Dr. Sorenson’s lab and finds the drawings for a project they’ve been working on, a “solar motor”, which he kindly corrects. When Sorenson’s assistant Dr. “Rich” Richie (Walter Maslow) shows Sorenson the corrected drawings, Sorenson is convinced that the Cosmic Man is benevolent, and instead of trying to track him down, decides to wait for the alien to make contact.

Col. Matthews is not on the same wavelength, especially not after the Cosmic Man causes panic by being seen by multiple people, prowling the nearby town and visting nearby someting-or-other refining/mining sites. Matthews thinks the visitor is a threat, and even worse, that the secrets of his technology might be learned by the Russians. This leads up to the finale, in which the military tries to kill the Cosmic Man, only to find that he has miraculously healed the little boy.

Background and Analysis

The Cosmic Man probably represented the efforts of three people to break into the movie business proper. Robert Terry’s sole screen credit before this was as associate producer on Boris Petroff’s clunker The Unearthly (1957, review), and The Cosmic Man remained the first and only film in which he acted as producer. For the purpose, he set up Futura Productions, which produced this film and no more. Terry bought the script from Arthur Pierce – his first screenplay for a feature film – for $600. As director he chose Herbert Greene, who did have a substantial career as an assistant director behind him, but had only directed one film prior, the no-budget western movie Outlaw Queen (1957), penned by Ed Wood. For star power Terry went to an old acquaintance, John Carradine, who had starred in The Unearthly. Carradine, who took any role offered to him regardless of the production, was game, and Bruce Bennett/Herman Brix also probably accepted any offers at this stage of his dwindling career.

The Cosmic Man was shot over six days, primarily at a hotel lobby set and in different parts of Griffith Park, including Bronson Canyon, in Los Angeles. The Griffith Observatory stands in for Pacific Tech, and the spaceship lands outside one of the entrances to the Bronson Caverns, so often seen in low-budget movies of the era. I have found no budget estimates of the film, but by the looks of it, it was somewhere probably around $100,000. Filming commenced in February, 1958, but it took producer Terry almost a year to find a distributor, until finally Allied Artists agreed to release it in January, 1959.

Good things can come out of low budgets and enthusiastic amateurs, but this requires a good script. And while Arthur Pierce would continue to write scripts for science fiction movies for several decaces, few of them can be considered “good”. From the start, the film’s problem is that it is so predictable. In the first ten or fifteen minutes we know exactly what we are up for. The Cosmic Man is clearly benevolent, and the picture is going to be a pacifist firebrand pitting the hawkish military man against the live-and-let-live attitude of the scientist. We know the military man is going to try to stop and kill the alien, who will be aided by the scientist. And we also know that the alien will cure the crippled boy in the end. In essence, this is a retread of The Day the Earth Stood Still. Benevolent alien comes to Earth to preach peace and understanding, but is thwarted by the suspiciousness and fear permeating cold war society. He befriends a young boy and his mother, as well as a pacifist scientist (whose equation he helps solve). In the end he is killed by the army, but is resurrected and flies off into the distance, leaving mankind to contamplate its warring ways.

The underlying story itself is not bad: it worked wonderfully in The Day the Earth Stood Still. However, that film was so iconic that the setup became a trope instantly. The film already had one carbon copy made in 1954, Stranger from Venus (review), and similar plots had cropped up ad nauseaum in film and TV over the decade. By 1959 it was essentially a meme.

Furthermore, the script is clumsily put together. The one female character in the film has no bearing on the plot whatsoever. Kathy’s sole function in the film is to provide romantic interest and act as mother for the boy. Pierce tries to further hammer home the point of the rivalry between the military and the scientific community – or between the warmongers and the pacifists – by having Col. Matthews and Dr. Sorenson competing for the favour of the beautiful widow. Had this competition been developed into a significant plot point, this might have been a good idea, but as the competition is lighthearted and amounts to nothing in the end, it just becomes padding and convention.

Pierce also crams in an overly obvious reference to Hiroshima and the nuclear bomb by casting Sorenson as one of the lead scientists on Project Manhattan – as if the audience was too dumb to make the connection without making the film’s protagonist personally responsible for the A-bomb. This is emblematic for Pierce’s screenwriting: the themes of the movie are explicitly S-P-E-L-L-E-D O-U-T for the audience in numerous conversations, rendering the issues at hand incredibly banal. An example:

Col. Matthews: “He’s a threat. We can’t just sit back and do nothing.”

Dr. Sorenson: “Science offers answers other than destruction.”

Col. Matthews: “Our duty is to protect this nation.”

Dr. Sorenson: “And our duty is to protect mankind’s future.”

Nothing very much happens in the film, and what does happen is both vague and off-screen. Almost all of the actions of the Cosmic Man are relayed to us in conversations after the fact, and the only scene with anything resembling action is a sonic boom which makes Dr. Sorenson topple over, to no ill effect. It’s a very static movie, driven by endless amounts of dialogue. Dialogue-heavy movies can be great, but then the dialogue needs to be good. Here the dialogue is filled with the kind of banalities featured above, as well as long stretches of pseudoscience that doesn’t make any sense.

But I hear you say: the film still has John Carradine. That’s got to account for something, right? Well, Carradine is barely in the picture. The Great Ham could usually elevate any script with his charismatic performance. However here, having procured the services of first-billed Carradine, the filmmakers decide to hide him for almost all of the brief moments that he does appear. Most of his appearances show the Cosmic Man as a semi-translucent shadow, with Carradine decked out in what appears to be a skintight suit with a baclava covering his face and a cape – optically inserted into the scenes as a negative image, making him appear as a black silhouette. Apparently he is “partly invisible during the day, but completely invisible at night”, owing to some thing or the other (really, it’s impossible to follow the bewildering science of the movie). When he is “partly invisible” he is decked out in a high-collared coat, a fedora and strange glasses that seem to have been bought from a prank store. And then, he only gets to stand stiffly and speak ridiculous lines in a haughty, monotone manner. Lines like “My people seek only knowledge and peace.”, “Science is the hope of your world.” or “You must learn tolerance before you join us.”

The alien is a source of confusion not just for the protagonists but also for the audience. It’s as if screenwriter Pierce simply couldn’t work out why the visitor came to Earth in the first place. Unlike Klaatu, the Cosmic Man isn’t here to deliver a message, in fact he doesn’t want to be discovered at all. He says that countless other visitors have been to Earth unnoticed, but he must be the clumsiest of the bunch. For a man who doesn’t want to be seen, he sure does cause a whole lot of commotion by showing up outside the windows of pretty much the entire village and gets the police and the military on his tail. He does give a number of soliloquys about mankind needing to cast off its warring ways before it can join he intergalactic community, but this doesn’t seem to be the purpose of his mission. At one point he says he is here to collect resources, but only such that humans have no use for, like sunshine. Later, however, we learn that he has been stealing “resources” – exactly what these are is never specified, but it seems like we are talking about stuff such as ore and minerals. So essentially it seems the “benevolent” aliens are strip-mining the Earth. Apparently, Pierce didn’t think this was enough of a reason for the alien’s visit, so he has Carradine state that he is also on Earth to take care of other business. When asked, quite understandably, what this other business is, he replies: “It’s better that you do not know”. And, apparently, it’s also better that the audience don’t know, because this is all we ever learn about it. All in all, the Cosmic Man’s presence on Earth remains a baffling mystery.

The reason for this, as Robin Bailes notes in his review at Dark Corners, is that the alien is only a MacGuffin – in the film solely to give the characters a reason to debate cold war issues with one another.

Despite the talkiness, the vagueness, the repetitive and weak plotting, the underdeveloped characters and the ludicrous science, the film does somewhat win the viewer over with its sympathetic nature. Pierce refrains from turning Col. Matthews into a villain. He is portrayed as a sympathetic and well-meaning, if misguided man, and the two main characters maintain a mutual respect throughout the movie. Pierce lets ideas fight, rather than people. This does make for a lack of dramatic situations, but feels quite refreshing in an era of blacks and whites and crudely drawn, antagonistic stereotypes. The feeling is enhanced by lead actor Bruce Bennett (real name: Herman Brix). While Brix was never considered a great actor, he had a natural charisma and an easygoing friendliness about him that translated well to the screen. Thus, he is superbly cast as the kind, warm-hearted pacifist professor of the movie. He has good rapport with child actor Scotty Morrow, who is one of the less irritating child actors of the era, despite being handed his fair share of “gee wiz” and “gosh” in terms of lines. Paul Langton, a seasoned character actor, also manages to balance his portrayal as the film’s – sort of – antagonist, making the Colonel as well-rounded a figure as the script allows for. Walter Maslow gives good support as Sorenson’s assistant. Lyn Osborn (of Invasion of the Saucer Men fame) is watchable as the twitchy Sgt Gray.

Herbert Greene was a seasoned enough assistant director that he knew how to set up a shot. The direction is workmanlike and somewhat dull. There’s a lot of master shots and few cutaways. Several scenes seem to be shot with a single setup, which was probably a result of the short 6-day shooting schedule. For example, several scenes in the Bronson Canyon are only ever shot from one direction, despite the fact that we spend what seems to be the majority of the film at that same location.

Design-wise the only thing that stands out is the alien ship itself. As a design it’s not particularly original, and looks like a giant golf ball. The fact that it doesn’t land so much as levitate a metre and ahalf above ground is, however, slightly original for its time, and the illusion is rather well executed. As far as visual effects go, the only real visual effect of note is the semi-transparent negative footage of John Carradine. The effect itself is not particularly good, but it is well composited into the master footage. Nobody is credited for visual effects, so cinematographer John Warren was probably responsible for the effects work – Warren was an Oscar nominated DP and knew his stuff.

The Cosmic Man’s greatest problem is its incompetent scripting. It’s not a terrible movie: the acting is fine and the cinematography dull but functioning. The special effects are so few and far between that their quality matter little. The movie sort of wins you over by being mostly harmless and sympathetic, but it’s just too dull and derivative to make any sort of impression.

Reception & Legacy

The Cosmic Man premiered in January, 1959 in the US, and seems to have played as a double bill to both House on the Haunted Hill and the crime movie Undersea Girl. It seems to have had a limited international release as well, shown at least in the UK and Mexico.

The movie received mixed reviews in the trade press. BoxOffice gave the film a good review, particularly on the strength of its minimal amount of horror elements: “This is just what the doctor ordered as concerns those censors of film fare who have been squawking long and hard because they think there is too much horror [in SF and horror films]” The reviewer called the story “imaginative but believable” and its cast “sincere.

Others were not as enthusiastic. Harrison’s Reports found “little to recommend” in The Cosmic Man, writing: “It’s chief drawback lies in the fact that it lacks appreciable suspense and excitement because it unfolds mostly by talk and has very little action”. The magazine called the story “only mildly interesting at best” and said “the direction and acting are so-so”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor also said that “Too little action hadicaps this science fiction entry which showed promise”. Powe in Variety was also negative, writing: “The Cosmic Man apparently was designed to be a thoughtful science-fiction thriller, but thought, as in drama, is no substitute for action, and certainly not when the thoughts are as banal as they are in this one.” Powe continues, saying that “the screenplay […] wastes considerable time on a diversionary interest, a handicapped child, that is particularly sticky”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies (1984), Phil Hardy strikes a more positive note, calling The Cosmic Man an “engaging, low-budget oddity” that “explores the idea of a benevolent alien trying to set Earth to rights”. He also, unlike most reviewers, feels that “the film’s optimistic ending has a certain naïve power.”

In Keep Watching the Skies! (2009), Bill Warren gives director Greene some credit, noting that the shots are well staged and make good use of limited sets, and that “the cinematography is moderately effective, moodily using shadows to good advantage”. However, he also feels the film is derivative, drab and talky.

Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant is forgiving: “In the end The Cosmic Man ends up as an inoffensive movie that might have been special if it were given a little more care and sensitivity in the direction department. Bennett’s good-natured humoring of little Ken’s interest in astronomy is handled fairly well, and the scientist vs. soldier opposition is at least allowed to develop. […] As clumsy as it is, this picture is okay.”

Cast & Crew

I have already reviewed 12 films here on Scifist featuring John Carradine (click the name link to see all of them), but I have yet to make a deep dive into his career – probably because it has felt like such a daunting task. But now I decided to take the bull by the horns, so here we go:

John Carradine must be regarded as the uncrowned king of science fiction and horror B-movies. The only one, really, that rivals him in terms of sheer quantity is Christopher Lee. Lee has IMDb credits for a whopping 74 sci-fi or horror movies, but Carradine has him narrowly beaten with 76. Boris Karloff, for example, trails far behind with “only” 52 credits. Interestingly, all of these actors were comparatively mature when they entered their horror/SF fame – Lee, the youngest, was 35 when he hooked up with Hammer.

John Carradine was born in 1906 as Richmond Reed Carradine, and later took the stage and screen name John Carradine, presumably as an homage to his friend and mentor John Barrymore. He grew up with an abusive stepfather and ran away from home in his teens, supporting himself as a street portrait painter. He nurtured dreams of becoming a stage actor after seeing a Shakespeare play as a child, and made his stage debut in his early twenties. He soon befriended another Great Ham, John Barrymore, which led to him getting hired by Cecil B. DeMille as part of the director’s stock company in 1927, primarily on the strength of his booming barytone – Carradine can be heard (and sometimes seen) in a dozen of DeMille’s movies.

The exact number of films Carradine’s appeared in is steeped in mythology – he has claimed close to 500, but only around half of that number have been confirmed – however one can add to that well over 120 TV shows. His first confirmed film appearance is from 1930, and for the next five years he appeared uncredited in a number of movies. Two of his early bit-parts were as an informer suggesting using ink in order to catch The Invisible Man (1933, review), and as one of the hunters happening upon the Creature in the blind man’s cabin in Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review). 1935 was a break-out year for Carradine, as this is when he started to be recognised as a valuable character actor and went from uncredited bit-part player to supporting actor in sometimes rather large roles. The main reason for this shift was the fact that he caught the eye of John Ford, who placed him in his “stock company”. Arguably, Ford gave Carradine his greatest dramatic roles from the 30s to the 60s. Especially well-remembered are his turns in Stagecoach (1939) as the dangerous but refined Hatfield, who becomes Claire Trevor’s guardian angel and dies a tragic death in the end, as well as in Grapes of Wrath (1940), in which he functions as the conscience of the film as Jim Daly, the preacher who has lost his faith and tries to find his new purpose in life, again ultimately dying a martyr’s death at the end. He’s also noted in a small but memorable role in the star-studded The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

Based on a number of stand-out supporting roles in serious dramas and westerns in the late 30s and early 40s, Carradine could arguably have carved out a successful career as a major character actor in A-films, however, larger-than-life performances and indiscriminatory attitude toward role choices soon trademarked him as a ham actor in horror, science fiction and other B-movies. In 1943 he embarked on an over four decades long career as a mad scientist with turns as a lab-coated villain in both Captive Wild Woman (review) and Revenge of the Zombies (1943, review). The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944, review), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944) and in particular his turns as Count Dracula in House of Frankenstein (1944, review) and House of Dracula (1945, review) established his immortality in the Universal monster cycle, with performances that were positively restrained compared to much of his later work.

With new leadership at Universal in the mid-40s, Carradine took a hiatus from film work to focus on his true calling, the stage, and appeared in several Broadway productions, but returned to the screen in 1954, and did one last “big” serious role as Aaron in DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956). It was in this period that his reputation as “the great ham” of low-budget movis was really formed. What is sometimes forgotten, however, is that despite “selling out” to whatever monster or alien movie that had need of his talents or marquee value, Carradine also continued to be consulted for A-list movies by big-name directors. Michael Curtiz cast him in several films, including the well-regarded Mika Waltari adaptation The Egyptian (1954) and the star-studded The Proud Rebel (1958) and John Ford featured him in The Last Hurrah (1958), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964). He appeared in Woody Allen’s Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex * But Were Afraid to Ask (1972), Elia Kazan’s The Last Tycoon (1976), Don Siegel’s The Shootist (1976) and as a voice actor in the animated The Secret of NIMH (1982).

That being said, the vast majority of John Carradine’s roles from the mid-50s onward were B- or Z-movies that exploited the actor’s marquee value and his authoritative, booming voice, as well as his no-holds-barred attitude towards playing villains, authority figures or other colourful characters. I won’t list all 40 science fiction films Carradine appeared in during his career. However, “highlights” among hs performances, according to several critics, are: 1. Invisible Invanders (1959), where he has a fairly small but memorable role as a reanimated scientist zombie puppeteered by aliens. 2. The Wizard of Mars (1965), where he appears as the floating head of the titular wizard, spouting “extraordinary, relentless dialogue, unbearably pretentious and frankly complete gibberish”. 3. The Astro-Zombies (1968), where he plays a “mad scientist [who] tries to explain his work to his mute assistant, who is intent on experiments of his own on a bikini-clad girl tied to a table”. 4. The Bees (1978), in which he again plays a mad scientist “chew[ing] the scenery even more so than is his wont”. 5. Frankenstein Island (1981), where he again appears as a floating head, this time the head of the deceased Dr. Frankenstein, directing bikini-clad native girls on an island on how to perform rituals keeping his 200-year-old assistant alive.

A whopping 40 of Carradine’s movies have an IMDb rating of under 4.0/10, which is generally reserved for the absolute bottom of the barrel (I have reviewed only a handful of movies with such a low rating, and I have given zero stars to movies with a higher rating). Carradine probably never turned down a role for other reasons than time constraints. He cared little for his reputation as a screen actor, as he never considered himself primarily a movie actor. Throughout his entire career Carradine performed on stage, and his great passion was Shakespeare. He had his own Shakespeare company, and made films for the sole reason of financing his stage work, and later in life, simply to pay the rent and keep his sons fed. About his acting he said: ““I am a ham! And the ham in an actor is what makes him interesting. The word is an insult only when it’s used by an outsider – among actors, it’s a very high compliment, indeed.”

John Carradine had five sons, three of whom became actors proper – David, Robert and Keith, who all went on to have rather successful careers. Many of his grandchildren also caught the acting bug. Best known of these is probably Emmy award winner Martha Plimpton and Ever Carradine, who had a recurring role in The Handmaid’s Tale (2017–2025). Outside of his acting, John Carradine was, as Jo Gabriel at The Last Drive-In puts it, “known for his theatricalizing, his out-of-control drinking, and his private life which was a circus. A life bombarded with non-conformity, chaotic marital trials and tribulations, arrests for not paying alimony, drunk driving, prostitution scandals, and bankruptcy that left him destitute.” His last years were marred by health problems. He gradually lost much of his eyesight and suffered severe arthritis, which nonetheless never kept him from acting, roaming and raising havoc. He passed away in 1988 – 82 years of age.

The patriarch of an acting dynasty, John Carradine left behind a stupendous legacy – from some of the best movies ever made to some of the absolute worst. He was perhaps best used by John Ford in poignant and memorable supporting roles in many classics – films in which he was given opportunity to display his serious dramatic talent. Fans of classic monster movies will celebrate him for his turns, twice as Dracula, in Universal’s original horror cycle. However, his most lasting legacy will be his prolific performances in schlocky B-movies. His commanding voice, impeccable, Shakespearean diction and his often over-the-top performances, never once winking at the audience, was often the factor that turned otherwise unwatchable movies into at least partly enjoyable ones. “If nothing else, the movie at least has John Carradine in it”, is one of the most common evaluations of films like Night Train to Mundo Fine (1966), Bigfoot (1970) or Vampire Hookers (1972).

Director Herbert Greene was primarily an assistant director for film and B-movies between 1945 and 1973, and primarily worked on westerns, crime movies and comedies. He directed only two films, the Ed Wood-penned western Outlaw Queen (1957) and the science fiction movie The Cosmic Man (1959).

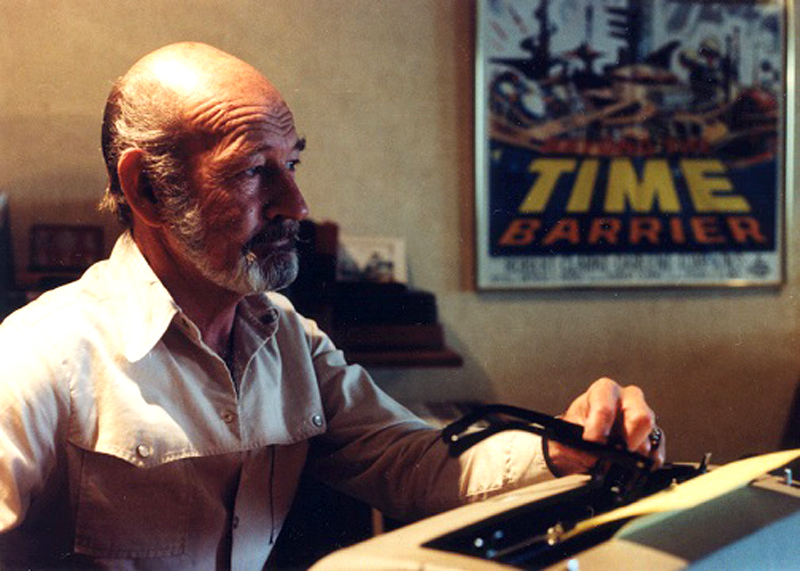

The Cosmic Man (1959) was the first screenwriting credit for Arthur C. Pierce, who wound up as a specialist in science fiction movie, both as screenwriter and director. Originally a cameraman, he got his start as a combat photographer during WWII, and upon returning from the war, studied drama and worked briefly as an actor and stage manager, before accepting a job at an industrial film company in 1948, and then in 1952 for a company that produced movie special effects. Reportedly it was Mark Hanna, the man behind Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958, review), that got him into screenwriting.

Between 1959 and 1978 Pierce wrote screenplays for 12 movies – all of them science fiction, many of them considered among some of the worst sci-fi films of the late 50s and 60s, but beloved by fans of schlock over the world. Or as filmmaker and friend Kevin Danzey put it: “low on budget but high on enthusiasm”. Best known of these are Invasion of the Animal People (1959), Beyond the Time Barrier (1960), The Human Duplicators (1964), The Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966) and Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966). He produced two science fiction movies himself and directed or co-directed six films, including his only non-SF movie, Las Vegas Hillbillys (1966). In the late 70s and early 80s he wrote several episodes for the TV shows The Next Step Beyond and Fantasy Island.

For more on Pierce, you can read Danzey’s very sweet obituary here.

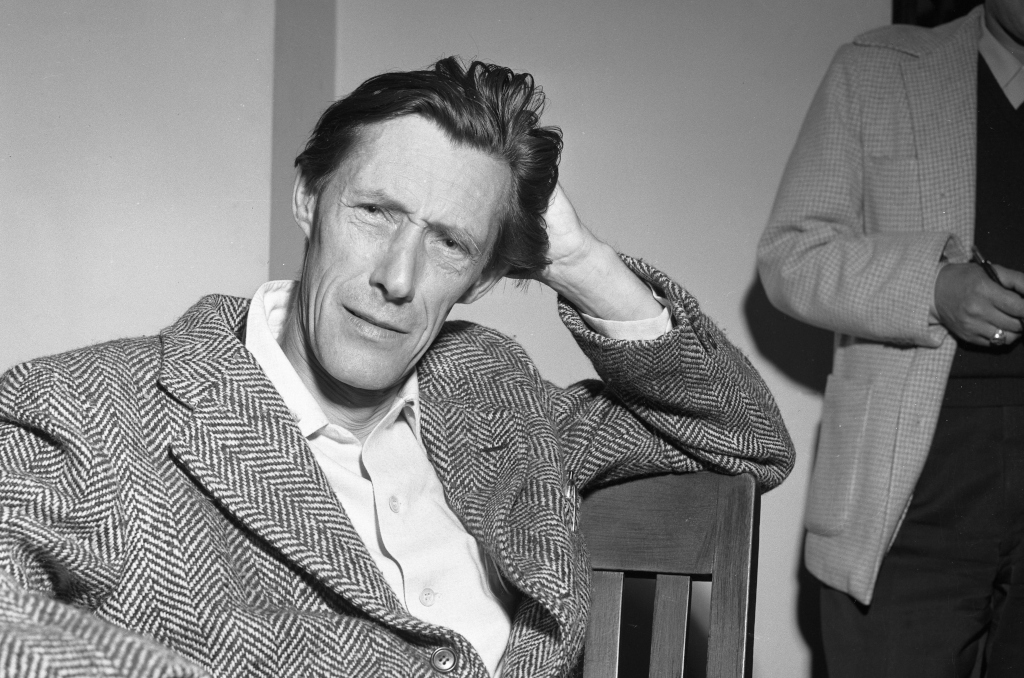

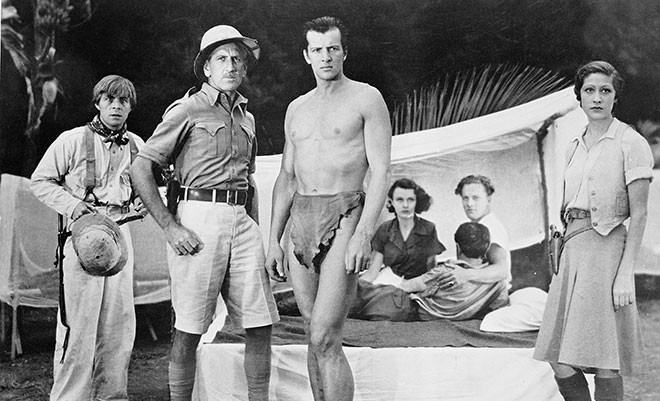

Lead actor Bruce Bennett was born Harold Herman Brix in 1906, played American football in college and was a track-and-field star, especially adept at the shot put. The crowning achievement of his sports career was a silver medal in shot put at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam. In the early 30s he moved to Los Angeles to compete for an LA sports team, but through his friendship with Douglas Fairbanks was lured into the movie business. This was of course a time before leading men built their careers on hitting the gym in order to sculpt their bodies, which meant that casting agents often looked to sportsmen in order to fill out roles in action films and serials. Swimmers in particular had that iconic comic-book V-shape, with broad shoulders, muscular yet lean, but Herman Brix also fit that profile. Thanks to his looks and his innate charming charisma, Brix was slated to star as the titular hero of the 1932 film Tarzan the Ape Man, but he broke his shoulder in his first film appearance in the football picture Touchdown in 1931, so the role went to multiple Olympic swimming medallist Johnny Weissmuller, and the rest is history.

Brix got his second chance in 1935 when Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs himself produced the 12-part serial The New Adventures of Tarzan, which was also edited into two different feature films. Probably because of Burrough’s involvement, this is one of the few times Tarzan is portrayed accurately, as an educated nobleman choosing to live in the jungle. The Tarzan role got Brix typecast in B-serials and Poverty Row features, and he played action heroes in several Republic serials in the late 30s. He starred in the sci-fi adjacent films Shadow of Chinatown (1936), opposite Bela Lugosi, and Sky Racket (1937, review).

As he was approaching his 40s in 1939, he decided he wanted to rebrand himself as a dramatic actor, took acting lessons and changed his on-screen name to Bruce Bennett. He got a contract at mid-tier studio Columbia, and one of his first roles for the company was the lead in the Boris Karloff vehicle Before I Hang (1940, review). Not a huge step up, but he did make it into A-movies – mostly in substantial supporting roles, but sometimes even as a co-lead, billed below bigger stars, like Humphrey Bogart, as in Zoltan Korda’s war movie Sahara (1943). He then moved on to Warner, where he got his arguably best roles. He had large supporting roles in Michael Curtiz’ Mildred Pierce (1945) and the Bette Davis vehicle A Stolen Life (1946). Bennett’s most prestigious performances came, again opposite Humphrey Bogart, in Dark Passage (1947) and best picture Oscar nominee The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948), both in featured supporting roles.

I have been a bit harsh on Brix/Bennett in some of my earlier posts. He didn’t make much of an impression in the leads of either Sky Racket or Before I Hang, but his on-screen charm does make him a pleasant actor to watch – and it does seem that he developed as a dramatic actor over the years. Nevertheless, he was a limited actor at best, and he saw his stocks dropping in the 50s. He was relegated to supporting parts in major studio B-movies, such as the Charlton Heston western Three Violent People (1956) and Elvis Presley’s debut feature Love Me Tender (1956). What leads he was able to secure were in independently produced no-budget pictures. As a result he partly dropped out of acting in 1960 to pursue a successful career in busines, although he did turn up from time to time, especially in the small screen, during the 60s and 70s, and he appeared in several episodes of Perry Mason and Lassie.

Herman Brix/Bruce Bennett appeared in a number of science fiction films during his career, most of them as a leading man, few of them particularly good: Shadow of Chinatown (1936), Sky Racket (1936, review), The Man With Nine Lives (1940, review), Before I Hang (1940, review), The Cosmic Man (1959), The Alligator People (1959) and The Clones (1973). He also appeared in five episodes of the TV show Science Fiction Theatre.

Irish-born model-cum-actress Angela Greene had longer and more prolific career than many of the beauty models that were chewed up and spit out by Hollywood, or decided/were forced to give up the business when they got married and had children. Unfortunately, that career was cut short in 1978, when she died of a stroke at only 57 years old. She has some SF pedigree: she appereaed in Jungle Jim in the Forbidden Land (1952, review) and played the female lead in two other science fiction movies, most notably the infamous Roger Corman production Night of the Blood Beast (1958, review), but also the John Carradine vehicle The Cosmic Man (1959). In 1976 she had a substantial supporting role as Mrs. Reed, one of the ill-fated guests at Futureworld, the sequel to the classic Westworld (1973). At one time, she dated John F. Kennedy.

In the role as the military representative in The Cosmic Man, we see Paul Langton, a respected but little-known character actor. We have bumped into him on this blog before, as the obnoxious lead in W. Lee Wilder’s terrible yeti film The Snow Creature (1954, review), and as the brother of the titular The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review). He also turned up in the cult classic It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review), as the spaceship crewman who is cornered by the space monster and fends it off with a blowtorch. Later, he appeared alongside SF veterans John Carradine in Allied Artists’ The Cosmic Man (1959) and John Agar in United Artists’ Invisible Invaders (1959). Furtherm, he had the honour of appearing in the very first episode of The Twilight Zone, as one of the doctors revealed at the end the episode, monitoring Earl Holliman’s astronaut trainee in an isolation booth. However, Langton’s definitive claim to fame is his recurring as the wily Leslie Harrington on the soap opera Peyton Place, a role he reprised in 219 episodes between 1964 and 1968.

The child actor in The Cosmic Man, as I mention above, is one of the less annoying child actors featured in 50s films. His name was Scott “Scotty” Morrow, and was an in-demand boy actor in the 50s and 60s, along with brother Brad Morrow. Born in 1946, he started his acting career in commercials and made his big screen debut in 1953. Some sources claim he appeared in the 1952 sci-fi crazy comedy Monkey Business (review), starring Cary Grant and Marilyn Monroe, however, there are no credits backing this up. His brother did appear in the movie, so it’s not impossible that Scotty also flickers past.

Morrow’s earliest film roles were uncredited bit-parts – including one in the popular Lana Turner vehicle Peyton Place (1958), which opened up for bigger roles. Still, he only had featured roles in a handful of B-movies in 1958 and 1959, including The Cosmic Man (1959). He was, however, more often seen on TV. Unlike his brother, he was never part of a TV ensemble, but turned up as a guest actor on numerous shows. He left acting behind when he turned 20, and embarked on a successful career as a Hollywood publicity photographer and at one point worked as an executive director at Paramount’s home video branch.

Among the bit players in the movie is John Erman, who went on to become a very successful TV director.

Janne Wass

The Cosmic Man, 1959, USA. Directed by Herbert Greene. Written by Arthur C. Pierce. Starring: John Carradine, Bruce Bennett, Angela Greene, Paul Langton, Scotty Morrow, Lyn Osborn, Walter Maslow, Herbert Lytton, Ken Clayton, Alan Wells, Harry Fleer, John Erman, Dwight Brooks, Hal Torey. Music: Paul Sawtell, Bert Shefter. Cinematography: John Warren. Editing: Helene Turner. Sound: Philip Mitchell. Special effects: Charles Duncan. Produced by Herbert Terry for Futura Productions & Allied Artists.

Leave a comment