An evil brain from outer space with designs of world domination takes over the mind of a nuclear scientist. Neatly directed 1957 indie no-budget effort starring John Agar. Very silly and lots of fun. 5/10

The Brain from Planet Arous. 1957, USA. Directed by Nathan Juran. Written by Jacques Marquette & Ray Buffum. Starring: John Agar, Joyce Meadows, Robert Fuller, Thomas Browne Henry, Dale Tate. Produced by Jacques Marquette. IMdb: 5.2/10. Letterboxd: 3.0/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 4.8/10. Metacritic: N/A.

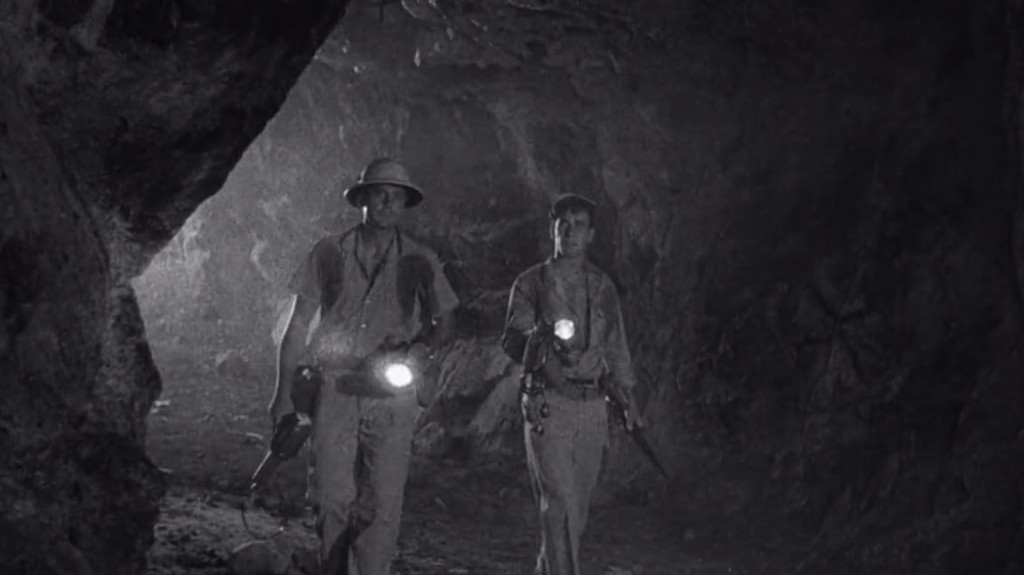

Nuclear scientists Steve and Dan (John Agar and Robert Fuller) drive out to Mystery Mountain to investigate strange bursts of radiation. They enter a cave where they are confronted with a giant floating brain with glowing eyes, which attacks and kills Dan and takes control over Steve’s mind. Steve then returns home to his fiancée Sally (Joyce Meadows) and her father John (Thomas Browne Henry), and tries to act normal, but Sally immediately knows something is up, when Steve is suddenly full of animalistic passion for her. He is also suffering from strange headaches, which he refuses to explain, and claims that Dan “went to Las Vegas”, which Sally realises is absurd. In reality, Steve has been body-snatched by an evil brain called Gor, from the planet Arous. Gor is planning to use Steve to get access to a nuclear test, where he intends to reveal his nefarious plan for world domination.

So begins 1957’s The Brain from Planet Arous, a cult classic directed by Nathan Juran and produced by Jacques Marquette, who both went on to make Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (review) in 1958. One of the better no-budget movies of the late 50’s, it serves up recogniseable faces and is a lot of fun.

Sally and John decide to take a trip to Mystery Mountain to try and find out what has happened to Steve. Here they find Dan, burnt to a crisp by radiation, and are confronted with another floating brain. However, this brain is named Vol and is a police brain from the planet Arous, out to eliminate Gor, who is a criminal and a madman (madbrain?). Vol explains that as long as Gor is inhabiting Steve, he is invulnerable, but once every 24 hours, he must leave Steve’s body and take on his true form in order to replenish his oxygen supply. That is when he can be killed when struck at a specific spot in the brain. Vol also says he needs to occupy Sally’s body in order to keep an eye on Gor. Hesitant, Sally instead suggests George, the family dog, and Vol thinks this an excellent idea.

Sally then plays along with “Steve’s” charade, but is still bothered by his sudden sexual lust, which emerges again when the two are out for a ride and “Steve” all but forces himself on her. All the while, he keeps talking about how he is going to become the most powerful man on Earth, come Friday’s nuclear test. We get a glimpse of his plans, when he uses his mental powers to blow up a random airplane in flight.

Friday’s nuclear test comes along, and Steve/Gor meets up with the army brass at the testing site, and reveals his powers by blowing up all of the site with his mind before they have the chance to test the bomb. Laughing like a maniac, he tells them he wants to meet with the leaders of all the great powers on Earth in 10 hours time, so he can explain to them all that he will make all humans his slaves. His intentions are to have them build weapons for his domination of the universe (brains have no opposing thumbs, so they can’t build stuff themselves, I suppose).

Back at home, Gor finally needs to replenish, and flops out of Steve’s body. Cleverly, Sally has left a note by Steve’s chair, showing him where to strike, and an axe. But will he notice?

Background & Analysis

The Brain from Planet Arous was the brainchild of Jacques Marquette. Marquette was a cameraman who struggled to advance to the rank of director of photography. In order to make it happen, he decided to beging producing his own films in 1957. He produced and filmed a small drag race movie Teenage Thunder for a low-budget distributing company called Howco International, and they went on to co-finance his second and third movies, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) and its double-bill companion, Teenage Monster (review).

In an interview with Tom Weaver, Marquette says that very much like Roger Corman, he had spent enough time on movie sets that he saw how much money the studios were wasting on overhead costs and on paying ridiculously high salaries to actors, directors and other staff, rather than paying them scale (the union mininum): “I knew a hell of a lot of people in the business that were not working (and would like to keep working) that would be more than pleased to work for scale.”

Ray Buffum had written the script for Teenage Thunder, and it was directed by Paul Helmick, an assistant director hungry to climb the career ladder. According to Marquette, the film did well, but through “creative accounting” Howco kept all the profit. That meant Howco also had to put up all the money for The Brain from Planet Arous, a meager budget of $57,000. Marquette says he wrote a 20-page outline for the story, but took no story credit, and handed it over to Buffum to flesh it out into a script. Many have pointed out the similarities between the film and Hal Clement’s novel Needle — a story in which an alien cop arrives to Earth in order to catch an alien crook, and both aliens need human bodies to operate. Marquette readily admits that he had “halfway stolen” the plot from a story had read in a pulp magazine. According to film historian Bill Warren, Needle appeared in Astounding in 1949 and was published as a novel in 1950. As director Marquette hired Nathan Juran, who had just come off working on Ray Harryhausen’s 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review). Juran, dissatisfied with the result of the film, chose to be credited under the pseudonym Nathan Hertz.

As opposed to most scenarists making science fiction movies in the 50s, Jacques Marquette was actually a science fiction fan. He tells Tom Weaver he read all the pulp magazines, and was thus up to date with what was going on in literary SF, rather than just the monster and UFO movies being made as cash grab in Hollywood at the time. The idea for The Brain from Arous is an original one for a movie, and taps into the body snatching idea that was prevalent in a lot of literary SF at the time, not only Needle, but also Jack Finney’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and even more closely related to the screen story, Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters. The film’s literary roots are also seen in the fact that rather than just state that the aliens are interested in female humans, we actually see a horny alien trying to mate with the leading lady, something which was probably often considered a bit too strong in a genre that was generally aimed at adolescents and teenagers. This may also be the first movie in which good aliens are hunting down bad aliens on Earth, creating an interesting twist on the alien invasion trope.

And while this isn’t a brain-in-a-vat movie per se, it is impossible to ignore the influence of the “original” brain-in-a-vat novel, Curt Siodmak’s Donovan’s Brain from 1942.

Unfortunately, Ray Buffum wasn’t the strongest of screenwriters, and the original premise is played out in a rather conventional way. The nuclear testing doesn’t play any part in the plot, but since the the threat of nuclear war was a staple in science fiction, it seems Marquette and Buffum just wanted to cram that in there too. The story is also hampered by its limited budget. Much of the film is played out at the Bronson Caverns, a favourite spot for low-budget filmmakers in Hollywood, and much of the rest at Marquette’s optometrist neighbour’s house (“he had a bigger house than we had”) and backyard, and some shots are done at Marquette’s house. The scenes with the meeting of the US military and the leaders of the world look like they could be filmed at an actual studio, but it might also be Marquette’s neighbour’s house. There’s enough backyard shooting and shots at remote roads in the hills that the film doesn’t feel too cramped, probably done guerilla style. But the limited sets also limits the story, and severely limits the menace presented by Gor. If he is invuneralble and can blow up the Earth with the power of his mind, why all the need for infiltration and secrecy?

Vol, the police alien, ultimately turns out to be a rather redundant character, and in the end doesn’t do anything but tell Sally where to bash the brain in. Having made much of his need to stalk Gor in dog form, all this stalking actually never amounts to either any information learned or action taken. Vol also brags about having “powers equal to or surpassing Gor’s”, suggesting there will be some cool alien showdown, which never materalises. When Gor finally takes on physical form Vol simply stands outside the window in the body of the dog, watching the proceedings. Of course, any alien death match would have required special effects that simply weren’t available for $57,000.

The special effects are poor, as can be expected at this budget. There is no special effects technician credited, but there are still a number of effects in the movie. There is, of course, the brain itself, which is not badly designed and realised as such – Marquette tells Weaver he gave a design pitch to a Hollywood props company, which designed and manufactured it. Two airplanes are blown up in the movie, obvious props being blown up, probably under the supervision of Marquette, who worked as the director of photography on the film. The coolest effects are probably the silver contact lenses worn briefly by John Agar as Gor goes into destruction mode. They look extremely uncofortable and that they were. Marquette tells Weaver Agar could only keep them on for 15 minutes at at time, and one shot is used several times. The lenses wera made by the same optometrist neighbour whose house the film crew borrows. Agar told Tom Weaver that the silver paint chipped away every time he blinked and got into his eyes.

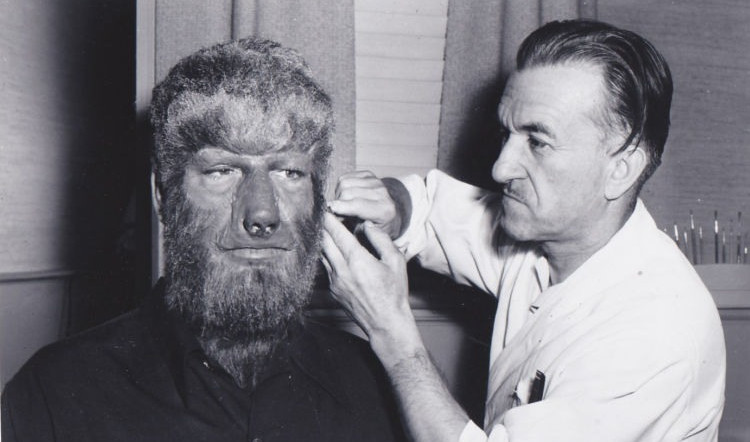

The shots of Gor blowing up the nuclear test site is, obviously, footage from a real nuclear test. Most of the time, the floating brains are giant and translucent, perhaps representing some mental image of the brains, and they grow and shrink in size. I’m not sure if they are supposed to be translucent or not, seeing as the model planes are also translucent. Marquette did all the visual effects in camera, in order to save money. The solid prop brain shown at the end naturally looks silly, but it serves its purpose. The makeup, includinhg the numerous radiation scars that show up in the film look surprisingly good for a movie of this budget. However, once you know who the makeup man was, it is actually not surprising. This was none other than legend Jack Pierce, who created the makeup for Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s Creature and the Mummy, as well as Lon Chaney’s Wolf Man, and so many other of Universal’s classic monsters back in the 30s and 40s.

Nathan Juran makes the most out of the script and the limited sets by keeping things moving and flowing. Even the cheapskate effect of simulating an explosion impact by shaking the camera and having the actors stumble around almost works, except you can see one of the actors wiggling a flag pole behind his back. Juran was never an especially stylish or innovative director, but he was a solid storyteller and knew his stuff. It is Juran’s strong direction that lifts this movie above the average late 50’s SF exploitation programmer. Even if he chose to be credited under a pseudonym.

The thing to take away from The Brain from Planet Arous is, surprisingly enough, John Agar – best known for being the bland, milqetoast leading man of so many lesser science fiction movies of the 50s. Agar must have relished in the chance to play a mad villain. Critics’ opinions about whether or not he pulls it off vary. Some are of the opinion that he isn’t able to escape his naturally kind countenance, but I think he does a great job, possibly one of the best of his career. There are several scenes in which he is downright chilling, and I think he does madness well, as well. The other standout performance in the movie is given by Joyce Meadows as Sally, a much deeper and more nuanced performance than we are used to seeing from female leads in films like this – she is helped here by a script that gives her a better than usual role to play. Robert Fuller as Dan is portrayed as the happy-go-lucky friend of Steve, and while the script doesn’t do him many favours, he is able to make the audience like him, which means there is a small sting of disappointment when he dies early. SF staple Thomas Browne Henry as Sally’s father has something of a nothing role, but as usual, he gives it his full commitment.

The Brain from Planet Arous is a very silly film. Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant suggests that the film should be viewed as a knowing spoof. However, I’m not sure to which extent the silliness was intended. At least, I don’t think producer Jacques Marquette intended it as a spoof. When asked by Tom Weaver about the spoofing in Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, Marquette denies that there was any spoofing involved, and that it was made as a serious film. Weaver doesn’t ask him about The Brain from Planet Arous, but I imagine he would have given the same reply. Of course, that doesn’t rule out the possibility that director Juran and the actors played it up a bit. But if it was intended as a spoof, then why didn’t Juran want his name on it?

Either way, this is a fun film, with a tight, straightforward plot, good direction and decent acting. The story, of course, is preposterous, and it is hard not to laugh at the silly floating brains and the cartoonishly megalomaniacal villain. It’s best not to start poking holes in the plot, as you’ll end up with a Swiss cheese. But that’s all part of the charm.

Reception & Legacy

According to IMDb, The Brain from Planet Arous premiered in October, 1958, and was packaged along with Marquette’s Teenage Monster (1957). Few trade outlets seem to have bothered with the film, and it took until January 1958 for Variety to write a review. However, according to the paper, the film was a “better-than-average entry in the seemingly endless scienticifiction cycle […] There’s good suspense worked into the […] screenplay”. Variety continued to praise John Agar’s performance, Nathan Juran’s direction and Marquette’s cinematography.

Today The Brain from Planet Arous has a 5.2/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on nearly 2,000 reviews, and a 3/5 star rating on Letterboxd, based on 1,000 votes. Rotten Tomatoes gives it a 4.8/10 critic consensus.

Steve Simels at Entertainment Weekly called the film a “fairly standard power-mad-alien-wants-to-have-sex-with-earth-women nonsense,” but that it was “redeemed by a few loony plot twists [and] nice tongue-in-cheek performances.” Kim Newman at Empire said it was “not-exactly-good” but has ” imaginative touches and wild ideas”. TV Guide said: “This may be really bad, but it’s good fun for the cult of John Agar fanatics”.

My go-to online critics have somewhat differing opinions on the film. Richard Scheib at Moria, who generally doesn’t have much good to say about the late 50’s low-budget SF movies writes: “The Brain from Planet Arous is a film that sounds wonderfully entertaining in synopsis […] On screen however, the film never lives up to such B movie luridness. It takes place with a straight-faced routineness and is drearily directed by Nathan Hertz.” However, Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant finds it hilarous: “This is the film in which to appreciate the singular talents of John Agar […]. Agar indeed carries the film, with a pleasant personality and a winning smile for every occasion. As just plain Steve, he’s not too interesting, but when possessed by the delinquent party balloon from Arous, he’s terrific. Agar never had a facility with dialogue, but he sure gives the comic-book threats he delivers to the Army brass and foreign representatives some snap, ending almost every sentence with a Simon Legree chortling laugh. The effect is as if Agar himself really did go nuts – it’s funny and weird at the same time.” And Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster says: “You can’t take this one seriously for a moment. But fortunately you don’t need to, as its fundamental goofiness is The Brain from Planet Arous’ greatest charm.”

Despite a lack of reviews, Glenn Erickson states that the film was a considerable success. Over the years, however, it fell into obscurity, before being rediscovered as a cult classic in the 80s. It has been spoofed in films like Ernest Scared Stupid (1991) and is included in the opening credit sequence in Malcom in the Middle (2000-2006). Gor’s megalomaniacal outbursts are included in Sony’s royalty-free sample library, and has been featured in films like Need for Speed II (1997) and House of the Dead 2 (2005), as well as in music by Deadmau5, Strapping Young Lads and many others.

Cast & Crew

Brooklynite Jacques Marquette moved to Hollywood with his family when he was still a child in 1919, and from his early teens started working small jobs in the movie business, eventually becoming a cameraman in the 40s. As he explains to Tom Weaver, graduating from cameraman to director of photography in Hollywood was a bureaucratic process, as producers were obligied by union rules to choose from any and all cinematographers that were already available before “promoting” a cameraman to DP. That’s why he took matters into his own hands and in 1957 decided to become his own producer. He had been saving and raising a small amount of money for his own film, the drag race movie Teenage Thunder (1957), and somehow distribution company Howco got wind of it, and wanted to co-finance and distribute it. A minor hit, it prompted Howco to finance two more movies for Marquette Productions, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) and Teenage Monster (1957), the latter which he also directed.

The Brain from Planet Arous was directed by Nathan Juran (under the pseudonym Nathan Hertz), and apparently he and Marquette had a good working relationship, as Juran went on to direct the two next (and last) movies that Marquette produced: Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) and Flight of the Lost Balloon (1961). The former, of course, has become a bona fide cult classic among SF fans. After this, Marquette had no need to produce his own films, as he was finally promoted to the status of director of photophy. He went on to steady work in the movies, and in his latter career, TV, and kept at until the late 80s. He also filmed the SF movies Last Woman on Earth (1960) and Varan the Unbelievable (1962), as well as a couple of SF TV movies and series.

Nathan Juran, born Naftali Hertz Juran in current-day Romania, moved to the US with his parents in 1912. He studied architecture and started his own firm, but with the constructing business grinding to a stop due to the Great Depression, he moved to Los Angeles in the late thirties, and started working in Hollywood’s art departments. During the 40’s he worked as an art director for 20th Century-Fox, was awarded an Oscar in 1942 for his work on How Green Was My Valley, and was nominated in 1946 for The Razor’s Edge. In 1949 he moved to Universal. When working on the horror film The Black Castle, he was asked to direct when the intended director dropped out two weeks before filming. Universal liked Juran’s work, and began giving him more directorial duties.

Juran primarily worked on B-westerns, but also the occasional costume swashbuckler. In 1957 he was assigned to his first science fiction movie, The Deadly Mantis (review). He then made a submarine movie starring Ronald Reagan for producer Charles Schneer at Columbia, which led Schneer, who had by then established his long-running collaboration with Ray Harryhausen, to assign Juran to work on the science fiction classic 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review). This led to Juran working on Schneer’s and Harryhausen’s first of many fantasy films based on classic Greek myth, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), which became both a box office and critical success. In 1962 he tried to recreate this success with Jack the Giant Killer, which he co-wrote and directed. However, the film received flack for its story, which blatantly ripped off the Harryhausen movie, and its stop-motion effects that deemed inferior to Harryhausen’s work.

Juran might have made a good living at Universal or another major studio, but wanted to get away from major studio restraints, and often worked for smaller outfits or independent producers, and had no qualms over accepting low-budget and schlock. In a later interview, he said he saw himself as a technician creating films for a living and not as an “artist”; “I always felt that my movies were temporary. They were just pieces of celluloid. You couldn’t eat them. You couldn’t sleep in them. You couldn’t use them in any practical way. So, I never really took the picture business too seriously.”

Apart from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Nathan Juran is best known for the four science fiction movies he directed during a span of two years in 1957 and 1958: The Deadly Mantis, 20 Million Miles to Earth, The Brain from Planet Arous (1958), and perhaps most famously, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). He returned to the genre (and Schneer) in 1964 with the H.G. Wells adaptation First Men in the Moon, co-written by Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale. He also directed episodes for a large number of SF TV series, particularly those produced by Irwin Allen. He directed his last film in 1973, before he returned to work in architecture.

Lead actor John Agar has become a symbol of the 50’s B science fiction movie, much to his own chagrin. Agar got a flying start to his career in 1946, when he had just married teenager and former child star Shirley Temple, and Temple’s producer David O. Zelznick discovered him and his good looks, and offered him a five-year contract including acting lessons. Agar did a number of high-profile supporting roles opposite stars like John Wayne and Kirk Douglas, but his carer suffered badly when his marriage with Temple ended, the press turned against him and his contract with Zelznick ran out in 1951. However, after a few rough years he was cast in the lead of the B horror film The Golden Mistress (1954), after which he was offered a seven-year contract with Universal.

Revenge of the Creature (1955, review) was Agar’s first role for Universal, and he hoped that his contract would finally give him his big breakthrough as a leading man. However, he was relegated to playing B movies, and William Alland especially liked him in his science fiction films. Agar played the lead in Tarantula (1955, review), and later in The Mole Men, a film Agar thought was so bad, that he said he would rather tear up his contract than appear in another one as lousy. He saw his contract with Universal going nowhere, especially as Universal was grooming leading men like Rock Hudson, Tony Curtis and George Nader. So he quit.

However, his roles didn’t necessarily get better. Straight out of Universal he found himself starring the horror film Daughter of Dr. Jekyll. This was followed by films like The Brain from Planet Arous (1957, review), Attack of the Puppet People (1958, review), Invisible Invaders (1959), Hand of Death (1962), Journey to the Seventh Planet (1962), Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966) and Night Fright (1967). In the late sixties his roles became more sporadic, and he partly withdrew from motion pictures, but happily took on smaller roles when they were offered. He appeared alongside a number of old sci-fi veterans in the bizarre fan fiction movie The Naked Monster, originally filmed in 1988, but partly re-shot in 2004, when much of the cast had died, and released in 2005. In the sixties he also did three TV movies for director Larry Buchanan, including Zontar: The Thing from Venus (1966) and Curse of the Swamp Creature (1966), both considered among some of the worst movies ever made.

Canadian-born (1935) Joyce Meadows grew up on a ranch, which served her well in later western movies, and became interested in singing and acting at an early age. Moving to California, she studied acting under Stella Adler and performed on stage at the Pasadena Playhouse, and other venues, and developed a particular liking for Shakespeare. In 1955, she started appearing in TV series, and in 1956 made her big-screen debut opposite John Agar in The Flesh and the Spur. She later played opposite Agar again in The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) and Frontier Gun (1958). Most of her Hollywood career was spent as a guest star in TV shows, and in 1965 she got disillusioned with the business and instead focused on her stage work. However, she returned to both the small and big screen in the late 80’s, and in 2022 made a cameo as both herself and her character in The Brain from Planet Arous in the low-budget spoof Not the Same Old Brain.

Robert Fuller started his acting career as an extra and a dancer, and Jacques Marquette’s Teenage Thunder (1957) and The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) provided him with his first substantial roles. However, he got his big break when landing a co-starring role in the popular western series Laramie (1959-1963), then went on to Wagon Train (1959-1965) and another co-starring stint in the hospital drama Emergency! (1972-1978). His most famous movie role is probably in the sequel to The Magnificent Seven, Return of the Seven (1966), when he took over the role as Vin, previously played by Steve McQueen. His last TV role was in Walker, Texas Ranger in 2001, after which he retired to become a rancher.

Thomas Browne Henry was an actor whom B-movie audiences of the late 50’s almost expected tos how up dressed in army fatigues. Sometimes in SF movies like Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), Beginning of the End (1957, review), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), Space Master X-7 (1958, review) and How to Make a Monster (1958, review).

One of the stuntmen on the picture is Gil Perkins, who was one of Marquette’s financers for his three Howco films. A legend among stuntmen for having been one of the people to don the Creature makeup in Universal’s original Frankenstein cycle, the Australian-born stuntman and bit-part actor went on to his only starring role in Teenage Monster (1957).

Makeup artist Jack Pierce, of course, is famous for having created the makup for Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, Jr., Bela Lugosi and many others during the golden era of Universal’s monster movies in the 30’s and 40’s. Pierce can almost be said to be single-handedly responsible for the modern image of Frankenstein’s Creature, the Mummy, the Wolf Man and Dracula. However, Pierce also had a reputation of being a perfectionist, making his actors suffer long and painful hours in the makeup chair, and for being a cantankerous self-styled “genius” who wanted to do things his way or no way, and was prone to getting into spats with colleagues. When Bud Westmore took over as the head of Universal’s makeup department in the late 50s, Pierce found that no other studio would hire him as department head, and he instead struck out as a freelancer, working mainly on B-movies, such as The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), Teenage Monster (1957), The Amazing Transparent Man (1960), Beyond the Time Barrier (1960) and The Creation of the Humanoids (1962). He rounded out is illustrous career as the resident makeup artist for the family comedy TV series Mister Ed (1962-1964), which must have felt like a rather disappointing swan song for the great master, even if it put food on the table.

The voice of Gor and Vol was done by Dale Tate, who worked at the film processing lab that Marquette used. According to Marquette, Tate had dreams of becoming an actor, so Marquette offered him the role.

Janne Wass

The Brain from Planet Arous. 1957, USA. Directed by Nathan Juran. Written by Jacques Marquette & Ray Buffum. Starring: John Agar, Joyce Meadows, Robert Fuller, Thomas Browne Henry, Dale Tate, Ken Terrell, Henry Travis, E. Leslie Thomas, Tim Graham, Bill Giorgio. Music: Walter Greene. Cinematography: Jacques Marquette. Editing: Irving Schoenberg. Makeup: Jack Pierce. Sound: Phil Mitchell. Stunts: Gil Perkins. Produced by Jacques Marquette for Marquette Productions & Howco International.

Leave a comment