Aliens land in Japan, and demand to mate with Earth women. The united military might of Earth engage in battle with the aliens. Ishiro Honda’s 1957 epic is a visual feast, but unfortunately thin on plot. 6/10

The Mysterians/地球防衛軍. 1957, Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Shigeru Kayama, Jijiro Okami, Takeshi Kimura. Starring: Kenji Sahara, Takashi Kimura, Yumi Shirakawa, Akihiko Hirata, Momoko Kochi, Susumu Fujita, Yoshio Tsuchiya. Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka. IMDb: 6.1/10. Letterboxd: 3.1/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

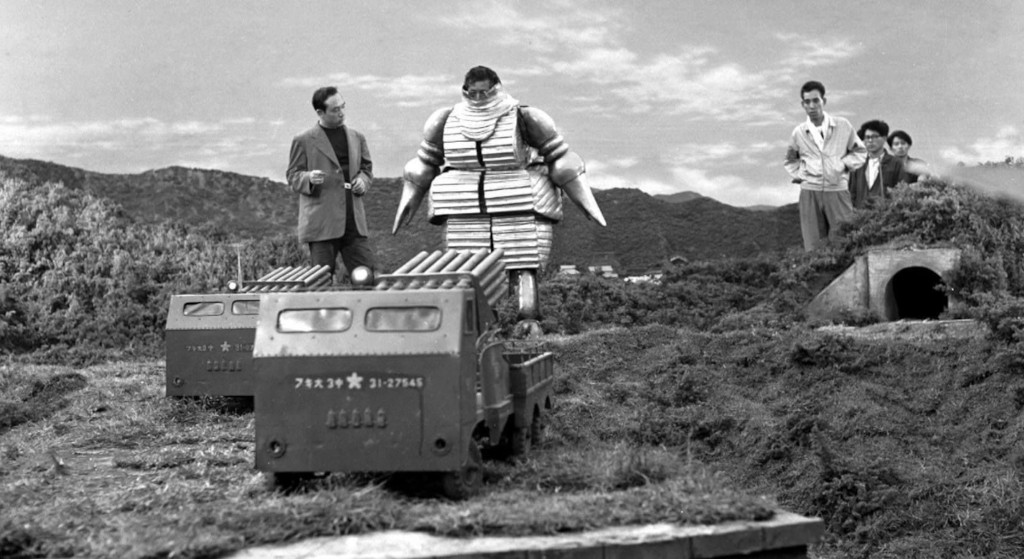

After strange forest fires, landslides and the appearance of a gigantic mecha-kaiju in rural Japan, which kills hundreds of people, astrophysicist Ryoichi Shiraishi (Akihiko Hirata) goes mysteriously missing. Shortly after, his boss, Dr. Adachi (Takashi Shimura) receives from him an unfished report on a group of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, which Ryoichi believes was once a planet, which he has dubbed “Mysterioid”.

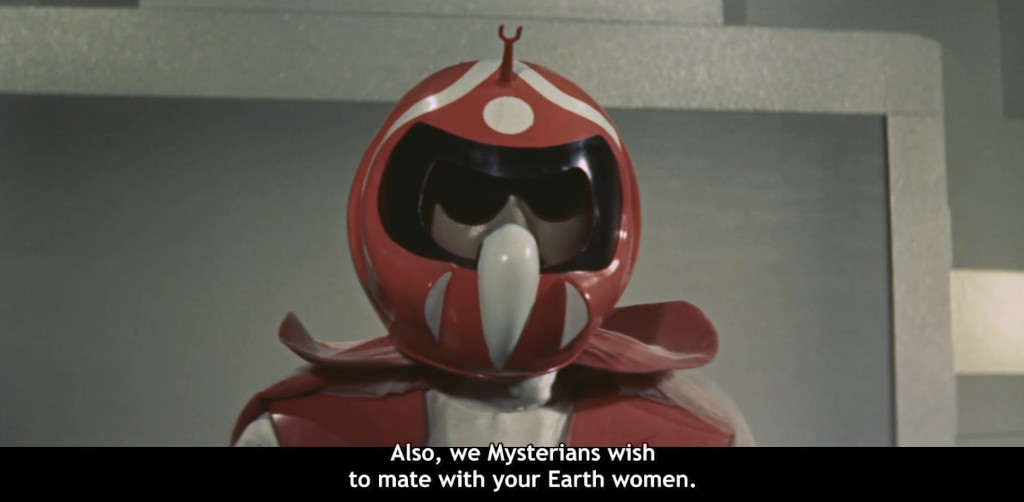

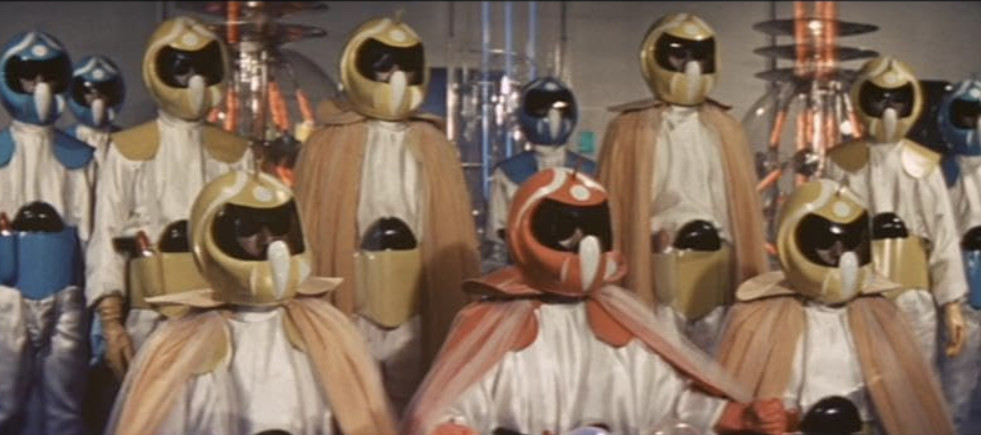

Soon, Adachi, Ryoichi’s colleague Joji Atsumi (Kenji Sahara) and a few other scientists are invited into an a large dome, which turns out to be a base for the alien invaders, the Mysterians, a human race dressed in colourful jumpsuits and biker helmets. The leaders of the Mysterians explain (Yoshio Tsuchiya) that Mysterioid was destroyed by a nuclear war, and they have come to Earth to save humans from themselves. The Mysterians accuse the humans of attacking their mecha-kaiju, even though the Mysterians only want peace. They explain that all they want is three kilometers of land around their base, as well as five hand-picked Earth women to breed with. Their race has been damaged by radiation, and thus they need new blood into their gene pool. Two of the women they desire happen to work for Dr. Adachi, and are Etsuko Shiraishi (Yumi Shirakawa), who is Joji’s girlfriend, and Hiroko Iwamoto (Momoko Kochi), who happens to be Ryoichi’s girlfriend. Landslides, fires and robot monsters the Earth scientists may have accepted as the cost of peace, but when aliens starts copulating with our women, they decide there is no other alternative than war.

Thus begins 地球防衛軍 (Chikyū Bōeigun, “Earth Defence Force”) or The Mysterians, Ishiro Honda’s 1957 science fiction epic. It was the first collaboration between Honda and Toho Studios’ special effects wizard Eiji Tsuburaya to be filmed in colour and the the newly introduced anamorphic TohoScope. A success both in Japan and in the US, it inspired the studio to make more space-themed SF epics. It was released as a US dub by MGM in 1959.

While Japan’s army is gearing for war, Ryoichi contacts Joji through the television sets, revealing that he has joined the Mysterians as a diplomat, and urges Ryoichi to make peace with the aliens, in order to prevent the destruction of Earth. However, Japan’s scientist and military will have no peace dictated by an alien force, and throw everything they’ve got at the aliens’ flying saucers and pulsating dome, to no avail. When the Mysterians start retaliating with death rays, Dr. Adachi makes a plea for all the world to come together to fight the Mysterians. Thus is formed the “Earth Defence Force”.

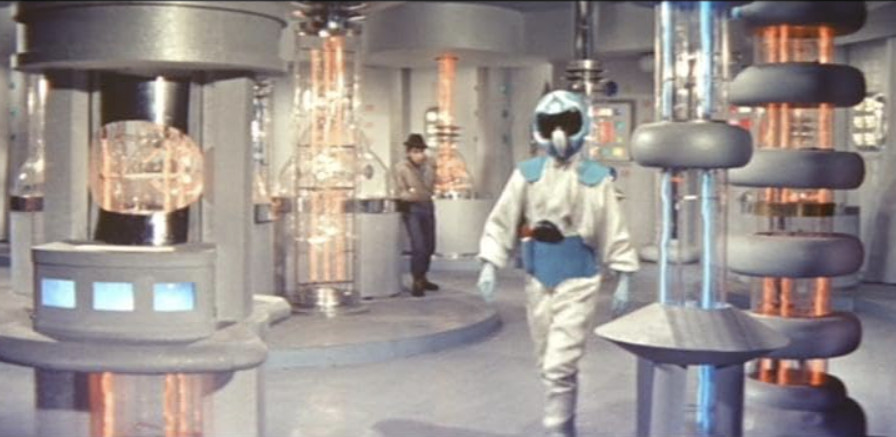

With the aid of the United States, Japanese scientists start working on a new weapons, including a series of rays that will neutralize the Mysterians’ death rays, and a novel electric cannon, that they hope will blow up the base. But first they stage another raid against the dome with heat missiles, but to no avail. Diplomatic meetings are held and tanks, planes and cannons launch their barrages against the impenetrable alien dome. Explosions, death rays, fire and smoke fill the the screen, as Earth battle the Mysterians.

Meanwhile, Etsuko and Hiroko are kidnapped by the Mysterians, creating a dilemma for Dr. Adachi and Joji: if they destroy the mysterians, the women will die as well. However, Dr. Adachi muses that their friends will have to become casualties of war. Joji will not hear of this, and sneaks into the dome through an underground passage. he knocks out a guard, steals his ray gun and comes to the rescue of the women. However, alarms go off and they risk being captured, when a Mysterian appears and tells them to follow him. He leads them into an underground passage and reveals himself as Ryoichi. Ryoichi says that the Mysterians have betrayed him, and hands Joji his finished report on the Mysterians, telling them to get out and deliver the report: the world must know the story of the Mysterians in order to save Earth from the same fate. He then runs back into the base, saying he still has unfinished business. At the same time, Earth Defence Force is launching their new super weapons, but due to problems mounting the electric cannon into a plane time is running out….

Background & Analysis

This is my last review of a film from 1957. Reviewing SF movies in a chronological order, 1957 has been the year with most movies for me to go through thus far, due to the explotion of teen monster movie and cheap exploitation monster films in the US. In 1957, science fiction was also beginning to establish itself – or make a comeback – in a number of other countries, such as the UK, Mexico and not least Japan, which was swiftly becoming the US’ biggest SF movie challenger.

In 1954, Ishiro Honda made the original Gojira movie, along with producer Tomoyuki Tanaka and special effects creator Eiji Tsuburaya. The film was a smash hit at home, and its reputation gradually grew internationally as well, giving birth to the kaiju genre, the particularly Japanese variant on the giant monster movie. Meanwhile, Honda became encouraged by the success of science fiction epics like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), The War of the Worlds (1953, review) and the growing popularity of space-themed movies, like Daiei Studios’ Warning from Space (1956, review). The time was ripe, thought Honda, to make a Japanese science fiction epic.

Naturally, Tanaka and Tsuburaya were back in board. Tanaka ordered a story treatment from science fiction author Jojiro Okami, which was then adapted by Gojira screenwriter Shigeru Kayama, who, among other things, added the mecha-kaiju, the plotline about the Mysterians wanting to copulate with Earth women, and a hint at romance. Finally, the script was polished by Rodan (1956, review) screenwriter Takeshi Kimura. Honda also gathered around him the stars from both Gojira and Rodan. Akihiko Hirata and Momoko Kochi played brother and sister in Gojira, and Takashi Shimura reprised his role as the elder scientist from the same movie. Kenji Sahara and Yumi Shirakawa were the stars of Rodan, and Yoshio Tsuchiya was one of the heroic pilots of Godzilla Raids Again (1955, review), making this a real all-star cast.

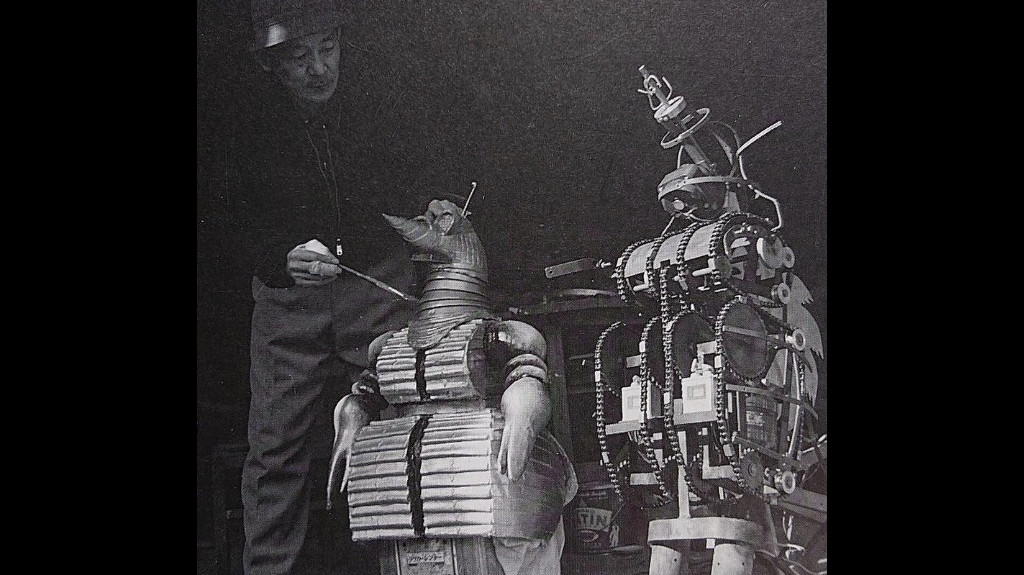

The Mysterians had a budget of 200 million yen, double that of the original Gojira, making it the most expensive tokusatsu (special effects) film to date. The sum was the equivalent of around $500,000. Technically and visually it is the most impressive of of Toho’s SF movies at this time, with effects stacking well up against Hollywood films of the era. As always with Tsuburaya, the miniature photography is excellent, from forest fires, landslides and sink holes opening up to swallow villages, to the superb model footage of military hardware battling the Mysterians and novel fighter planes and super-weapons. The design of the UFOs is clearly inspired by the manta ray-design of the alien machines in The War of the Worlds, but with their glowing underbellies, they have a wholly unique look. The domed base, able to descend into and ascend from the underground is also novel, with its drill-like disc on top, enabling it do dig through the Earth. It does feel as if Tsuburaya might have been inspired by the domed alien base in Quatermass 2 (review), but with its colour-changing nature and moving parts, it is also quite a unique and clever design. Credit for these should go to production designer Teruaki Abe.

If the visuals are the strong point of the movie, then the script is its weakest. The plot here is paper-thin, and at 90 minutes the film is way too long to sustain it. Most of the film’s running time is taken up by live-action footage of the Japanese military throwing everything they’ve got at the aliens, or miniature footage of the Japanese military doing the same. Toho clearly got all the support and assistance they needed from the military — this is no fuzzy training stock footage as in Hollywood movies, Honda seems to have had full access to as many soldiers and as much hardware he wanted. However, while all these scenes are very impressive, they are simply too long and repetitive. After watching it, I feel like three quarters of The Mysterians is just footage of tanks, cannons, planes and soldiers unloading on a dome. There are four major battle sequences in this film, all varying very little, apart from the fact that the Earth Defence Force ups its hardware with every bout. These all go on for at least ten to fifteen minutes at a time, if not for longer.

These scenes are intertwined with endless scenes of conferences. There are at least ten scenes depicting meetings or conferences, usually amounting to little less than the Earth forces unvailing a new weapon. This leaves no time for drama or character development. The movie also suffers from what seems to be a staple in these tokusatsu films, the lack of a clear central characters. Ryoichi is set up to be the central hero, but then he disappears for most of the movie, and Joji is put forth as the hero. But Joji has little to do until the 70-minute mark when he literally puts on his hero hat and infiltrates the alien base. Dr. Adachi seems to be set up as the leader of the Earth forces, but when the military gets involved, General Morita (Susumu Fujita) takes over this role. So much time is spent on the military excercises, that we don’t even get any time for romance, and the two female leads hardly have more than ten lines between them in the movie. All they seem to do is serve tea. This is a sausage fest from beginning to start.

The proceedings also seem slightly haphazard. The kaiju in the beginning feels just like the afterthought that it was — appearing for ten minutes or so, getting blown up and never appearing again until the very end, when it is revealed as an alien digging machine. Why it causes forest fires is never quite explained, although it is apparently radioactive. In a later scene, we see it burrowing underneath the ground, and its name (which was only revealed after it appeared in later films) is Mogera, which is derived from the Japense word for “mole”. Thus, it is supposed to resemble a giant mole, but it more closely looks like a giant chicken. It’s also obvious that the subplot concerning the kidnapping of the women is tacked-on. The two leading ladies have no real characters to play — they exist in the film only to be abducted, and then we don’t follow their ordeals at all, until Joji comes to the rescue. Yoji, as stated, is just a bystander in the movie until, at the end, he suddenly becomes the hero — just before Ryoichi steals the hero mantle from him, as the original story was written.

All this said, there are themes in The Mysterians worth exploring. Honda’s Gojira was, as we know, at its core a very political movie, dealing with the Japanese experience of WWII, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the American nuclear tests outside Japan, and the devastation of the nuclear bomb. Gojira has an ambivalent message about science’s potential for both humanity’s destruction and its salvation. The same theme runs as a thread through The Mysterians. This ancient alien race has destroyed its home planet through the means of nuclear weapons and are ostensibly on Earth warning humans not to follow in their footsteps. This is a trope, of course, lifted form The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review). Ryoichi, in joining the Mysterians, puts his faith in science as the salvation of mankind. At one point he states: “Who rules us? The Japanese? The Mysterians? No. Science rules us all.” Ryoichi imagines science as an obective neutrum, or even more precisely, as an unfallable almost godlike power. What screenwriters Okami and Kayama, as well as Honda, reminds us of is that science itself is not good or evil, but can be used for both, depending on who uses it and for what purposes. There is one point in the film where the military have failed to make even a dent in the aliens’ defences, and state that there is no choice less but to resort to nuclear bombs, and Dr. Adachi solemnly states that this is a path that we must never take, reminding us that there is always a choice to use or not use our knowledge in certain ways.

The Mysterians doesn’t have the trite message of “there are some things man should not meddle with”, it is not an anti-science film. In the end, like in Gojira, it is science, and particularly military science, that wins the day. The Mysterians are not defeated, like in The War of the Worlds, by the common cold, or by diplomacy, religion or the innate goodness of mankind, but through a new super-weapon developed by the combined military and scientific efforts of the nations of the world. This is also what makes the message of this film muddled. Despite all the talk about peace, Earth never even considers negotiating with the Mysterians. It’s just kaboom from the get-go. More than anything, the film resembles a commercial for the Japanese military.

While it is at least partly by design, the ambivalence surrounding the Mysterians’ motives makes for a somewhat confusing film. It is unclear whether the mecha, Mogera, in the beginning is carrying out a deliberate attack or if it just causes destruction sort of by mistake. The Mysterians accuse the Japanese of beginning the hostilites by attacking Mogera. A somewhat feeble argument, seeing as the robot previously caused an entire village to be swallowed by the Earth, caused devastating forest fires and razed another village to the ground. But hey, maybe it was an accident. In the beginning it sort of seems like the Mysterians actually have good intentions, even if they are going about things in a severely backwards manner. And even in the end, I can’t help but feeling that all this devastation could have been avoided, had the two parties actually sat down and tried to reach an agreement. Of course, if the Mysterians’ plan had been to colonise Earth all along, then discussion would have been futile, and Earth’s hostile reaction was entirely justified. The problem is that the film never establishes beyond a doubt that this is the case. Honda had probably seen Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), in which aliens arrive to Earth with seemingly friendly intentions, but are revealed to be wolves in sheeps’ clothing. But Columbia’s film was clearer on this point.

Ishiro Honda later stated that he wanted move on from the cold war-themes still prevalent in earlier kaiju and tokusatsu movies, and present a vision of Earth united against a common threat. Still, there is a bombastic note of Japanese nationalism embedded in the film, and viewers no doubt took pride in seeing Japan presented as the leader of the world, just a little more than a decade after the end of the American occupation.

There is a curious thread running through many of the Japanese science fiction film, particularly those directed by Ishiro Honda, that they lack a clear central character as the hero. Threats are met by the people as a collective, and there is a strong emphasis on collective decision-making, as illustrated in The Mysterians by the endless succession of scenes depicting meetings and conferences. Few characters in these films take independent choices, and when they do, they are often problematic. In the rare cases that individual actions save the day, it is usually a case of a character sacrificing himself for the good of the collective — in fact, Akihiko Hirata dies saving the world in both Gojira and The Mysterians. This emphasis on collective is one that runs deeply in Japanese culture, as a counterpoint to the American individualistic narrative, where it is often the maverick hero that single-handedly saves the day. While this emphasis on the collective is in a way refreshing, it also creates problems for the filmmakers, as these movies often include too many characters for the viewer to keep track of, and as much of the running time is often taken up by monster action and special effects, little time remains for getting to know the characters or setting up personal drama. This means that it is difficult for a viewer to get involved in the film on an emotional level. The Mysterians is an extreme case of this.

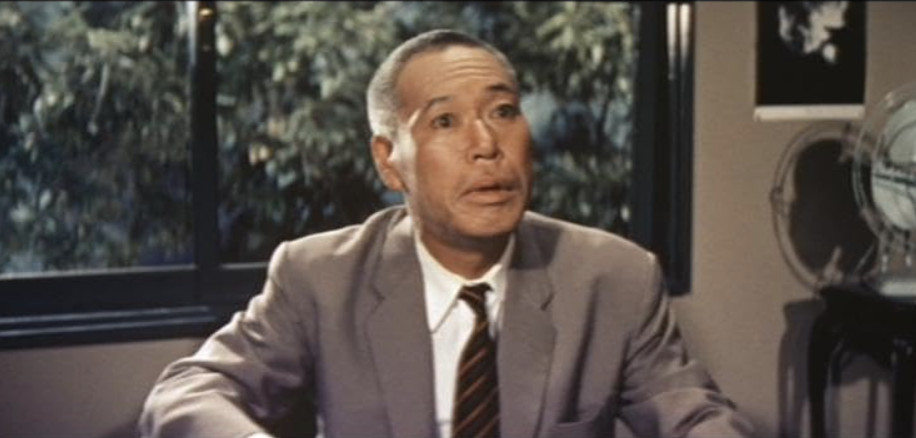

Evaluating the performances is difficult, as the main characters have so little screentime. Takashi Shimura reprises his role as the gentle but upstanding elderly statesman of the film, commanding the screen whenever he is in it. Kenji Sahara is also quite adequate as the closest thing the film comes to a leading man. Akihiko Hirata easily breezes through his ultimately small but central role. Yoshio Tsuchiya has developed an interesting staccato movement pattern for his role as the alien villain, which goes well with the similarly staccato speech pattern of the aliens, suggesting that Mysterians, through their reliance on technology, have became almost robot-like. The story goes that Tsuchiya, a major movie star, was offered to play Joji, the hero, but found the prospect of playing the alien villain far more exciting. Honda explained that he would not be recognised behind the helmet, but Tsuchiya took this as an acting challenge, by which Honda was impressed. Momoko Kochi, she with the cute overbite, looks desolate like only Momoko Kochi can look desolate. The weakest performances are given by the American actors, who, as was generally the case with Western performers in Japanese movies, were not actors, but rather Western expatriates, of whom many found work in Japanese movies. In his review at Dark Corners, critic Robin Bailes riffs what he thinks is a bad US dub in a scene where an American scientist storms into a conference with weapon blueprints, exclaiming a particlarly weak delivery of the line “Good news, good news!” However, this is not a bad dubbing, but taken from the original performance by tax accountant Harold Conway.

Speaking of dubbing: Some reviewers watching the dubbed version have ridiculed the fact that when speaking of the asteroid that was once the planet Mysteriod, as well as the former planet, the person dubbing Takashi Shimura uses the word “star” to describe them, rather than “asteroid” or “planet”. However, this is not a dubbing or translation issue: in the original Japanese version Shimura actually uses the word “hoshi” or “star”. This is not a case of the screenwriters not knowing the difference between a star and a planet, but rather a question of idiomatic expressions. Back before we all knew about the difference between stars and planets, they were all just bright lights in the night sky, and in different languages, we called them stars. While planets, moons, asteroids, comets and other celestial objects got their own names as our knowledge of the universe grew, many languages still kept using the word for star to describe any celestial object: “star” came to be both the exact term for actual stars, and a collective term for celestial bodies. For example, in Finnish, the word for star, “tähti”, was often used, just a few decades ago, to describe planets, so that one might idiomatically speak of “Mars-tähti” or “the star Mars”, even if one knew the difference between a star and a planet. The same is true for the word “hoshi” in Japanese, and even the word “star” in English, even if it is not very prevalent today.

How much you like The Mysterians will depend on how much you enjoy watching battle footage. As stated, the battle scenes are excellently staged, with great live-action footage of the Japanese army in action, and the model and miniature footage is remarkably well executed, even if there are signs here and there that Toho didn’t quite possess the resources or know-how of major Hollywood studios when it came to delivering big-budget special and in particular visual effects. To my taste, though, these scenes are too long and too repetitive, and several shots are re-used not only once, but sometimes twice or even thrice, suggesting that editor Koishi Iwashita struggled to bring the film up to the desired 90 minutes. Nevertheless, the non-stop action, the great effects and the interesting design make for an entertaining, if somewhat dramatically thin, affair. If you like Angry Birds, you will love the alien costumes.

Reception & Legacy

The Mysterians premiered on December 28th, 1957. The film earned ¥193 million during its initial theatrical run, making it Toho’s second highest-grossing film in 1958, and the 10th highest grossing film in Japan overall. The distribution rights for the United States were sold to RKO, who provided the English dubbing, but the rights were sold on when RKO started folding in 1958, and ended up with the theatre chain Loews, formerly the sister company of MGM. The film was then released by MGM in May, 1959 and grossed nearly a million dollars.

I have not been able to find contemporary Japanese reviews of the film, but it got moderately positive reviews in the US trade press when it was released overseas in 1959. Harrison’s Reports said: “From a production point of view, this Japanese-made science fiction thriller […] is far better than most American-made pictures of this type. […] Although the story offers little that is novel, the action holds one’s interest well”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor wrote: “There is enough fireworks, shooting, flying saucers, ray guns, all-out bombing, earthquake, fire, etc., for a dozen ordinary pictures. It all unreels, however, in fascinating, suspensful fashion, once you get accustomed to the Japanese actors and dubbing.”

Ron in Variety called The Mysterians “as corny as it is furious”, and continued: “While Junior may be moved by the arrival of outer space gremlins, big brother and all his friends will laugh their heads off.”. He continued to praise the special effects and high production values, but found the story somewhat confusing, blaming it on the dubbing. The Film Bulletin gave the movie 2.5/4 stars, citing “spectacularly imaginative technical photographic effects coupled with a handsomely-mounted CinemaScope Eastmancolor production”, and noted that the special effects “are the real attractions, and the plot definitely plays second fiddle”. Interestingly, in 1959 the magazine wrote as a warning to exhibitors: “From the boxoffice standpoint, it must be recognized that the market for science fiction films has dipped far below what it was a season or two back”.

Today The Mysterians has a respectable 6.1/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on around 2000 votes, and a 3.1/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on nearly 3000 votes.

Jon Davidson at Midnite Reviews gives the film 6/10 stars, writing: “For complementing alien warfare and monster mayhem with political commentary, The Mysterians earns its reputation as a Toho classic. Nevertheless, casual viewers may wish to avoid this movie for its awkward pacing and dated special effects.” Christopher Stewardson at OurCulture calls the film “a mammoth sci-fi spectacle, featuring giant lasers, flying saucers, underground domes, alien invaders, and robot monsters”, and continues: “Lying beneath its visual prowess is a set of questions, themes, and ideas that elevate The Mysterians as one of the decade’s most fascinating films”.

And Richard Scheib at Moria Reviews gives the film 2.5/5 stars, saying: “The plot of The Mysterians scours some of the hoariest cliches of pulp science-fiction and offers up an entertaining blend of giant flying robots, rayguns, UFOs and bubble-helmeted aliens abducting human women. The effects are variable – the giant robot looks like a fat, clunky anteater, while the opticals for the ray blasts look extremely cheap. However, the attack on the dome with scenes of the aliens blowing up planes and melting tanks and with humanity launching a special rocket to save the day is most entertainingly mounted. Certainly, up against this, the human element is almost entirely irrelevant.”

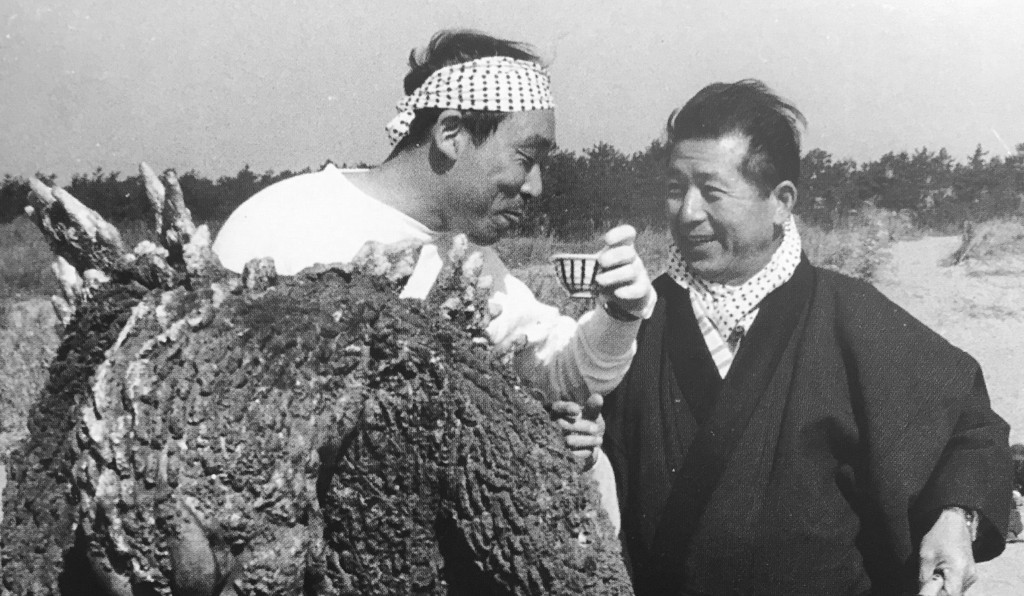

Mogera, for some reason often anglicised as “Moguera”, as if the robot was Hispanic, was the first mecha kaiju introduced to the big screen by Toho. As opposed to many of the other monsters that cropped up over the 50s and 60s, Mogera wasn’t brought back to the screen to fight Godzilla during Toho’s initial kaiju run that ended in the mid-70s. Perhaps the suit was awkward for stunt performer Haruo Nakajima, perhaps Toho decided that Mogera didn’t belong to the Godzilla universe, or perhaps Mogera just wasn’t deemed a very good monster. The character got an update, however, in the 90s, and first appeared in Godzilla vs. Space Godzilla (1994), and it returned in a couple of animated TV shows.

Cast & Crew

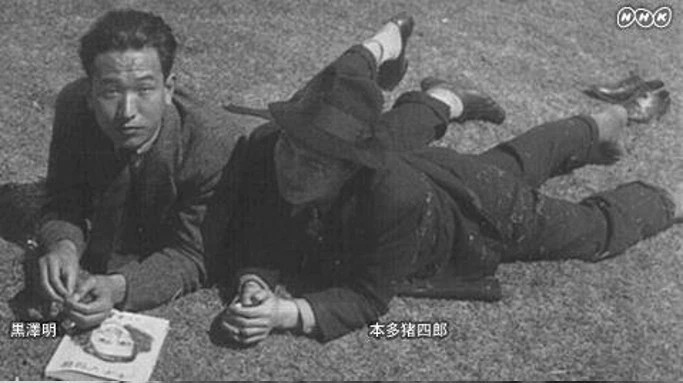

After graduating from film school in 1933, at the age of 22, Ishiro Honda immediately started working as ”assistant assistant director” for a number of directors, and in 1935 he enrolled in the army. During this time, he worked on a number of pictures together with a young Akira Kurowawa, up until WWII. For Honda, the next decade would be spent alternating between the trenches of war and the movie sets. In 1945, on campaign in China, Honda was captured as a prisoner of war, and got left behind as the war ended. He was released in March of 1946 after six months in a Chinese prison camp, and then decided to dedicade his life full-time to the movies. In 1949 Honda worked as first assistant director on rising star Akira Kurosawa’s Stray Dogs, which opened new doors for him, and in 1951 he finally got to make his directorial debut with Aoi shinju (The Blue Pearl). Another important film was his 1952 movie The Man Who Came to Port, not so much for the movie itself, but because it was here he met Tomoyuki Tanaka and Eiji Tsuburaya. The first ended up producing Gojira and the latter created the memorable special effects.

Honda and Tsuburaya teamed up again in 1953 for the effect-heavy Eagle of the Pacific. One of the film’s stars was Takashi Shimura, a favourite of Kurosawa’s who would later play Dr. Yamane in Gojira and Dr. Adachi in The Mysterians. For one of the many special effects shots of the film, Eiji Tsuburaya needed a plane to burst into flames with an actor in the cockpit. He wanted a brave/foolhardy actor with a good physique to pull off the stunt, and approached a 24-year old contract player called Haruo Nakajima. Nakajima went on play Godzilla and a slew of other monsters, including Mogera in The Mysterians.

Of course, 1954 saw the above named artists combine their forces in Gojira, and the rest is history. The film was a smash hit in Japan, and its fame also slowly grew internationally, making kaiju movies the cash cow of Toho Studios. Honda became Toho’s most prized science fiction and kaiju director, and continued directing these films during the entire Showa era (1954-1975), after which little remained in the franchise that was recogniseable from the original movie. After this, Honda went into retirement.

Takashi Shimura was one of Japan’s most praised character actors in a career that spanned six decades. He was a favourite of Akira Kurosawa’s because of his charisma and verisimilitude. In 1954 he was at the height of his career. He played one of his few leading roles in Kurosawa’s Ikiru in 1952, a film that won both the Kinema Junpo and the Mainichi awards for best film of the year, and his role earned him a Bafta nomination for best foreign actor. Another one of his best remembered roles came in 1954 when he played Kambei Shimada in Seven Samurai, which earned him yet another Bafta nomination in a film seen by many as one of the greatest in movie history. All in all, Shimura appeared in over 250 movies, 20 of them for Kurosawa. But he was no stranger to Toho’s tokusatsu, either. He reprised his role as Yamane in the sequel Godzilla Raids Again (1955, review), appeared in Honda’s The Mysterians (1957), had small roles in Mothra (1961), Gorath (1962) and Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964), Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965) and Prophecies of Nostradamus (1974). His last film was a small part in Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980), which Kurosawa had written especially for Shimura. He passed away two years later.

Another actor who became closely associated with Godzilla and the Toho tokusatsu eiga was Akihiko Hirata. With his thin face and cool visage, Hirata became a respected character actor, often playing sinister military types, but also a cult actor withing the tokusatsu genre. He appeared in 20 of Toho’s special effects films, and others, including Rodan (1956), The Mysterians, Varan (1958), The H-Man (1958, review), The Secret of the Telegian (1960), Mothra, Gorath, King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), Atragon (1963), Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, Ebirah, Horror of the Deep, The Killing Bottle (1967), Son of Godzilla (1967), Latitude Zero, Prophecies of Nostradamus, Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975), The War in Space (1977), Ultraman: Monster Big Battle (1979), Sayonara Jupiter (1984), and the low-budget TV movie Fugitive Alien, produced by Eiji Tsuburaya’s sons. He also had an important recurring role in the original Ultraman TV series.

Lead actress Momoko Kōchi’s role in Gojira led to her being typecast in sci-fi movies, and she appeared in Jû jin yuki otoko (1955, review), The Mysterians and other B movies, until she had had enough, and decided to pursue a formal actor’s training. This led to a successful career on stage, and thereafter she only occasionally appeared in films. In later years she told CNN in an interview that she loathed being associated with Godzilla. However, as with many former B movie actors, she came to embrace the cult fame in as she got older. Even to the point that she accepted a cameo to reprise her role as Emiko in the 1995 film Godzilla vs. Destroyah, which turned out to be her last movie.

Haruo Nakajima was the master of suit acting from the fifties to the early seventies. He appeared in over 20 of Toho’s science fiction movies, almost always in a suit, and many times as Godzilla. Nakajima took pride in never backing down from a challenge, whether he had to be buried alive, hoisted on wires, submerged, set on fire or have explosives placed on his body while wearing the suit. A very strong man with great endurance and trained in martial arts, he was the ideal suitmation actor. However, it wasn’t before the sixties that he started to receive screen credit for his roles. Like Universal with Frankenstein (1931, review) and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), Toho didn’t want to make the audience think about the fact that there was a man under the suit, let alone put a name to that man. This didn’t bother Nakajima, who instead relished in the respect he got from the people at the studio. In the sixties, he got an offer to move to Hollywood to do suit work, but stayed in Japan at the request of Eiji Tsuburaya, who said that he couldn’t do Godzilla without Nakajima.

Although not yet fifty and still in good physical shape, Nakajima retired after finishing Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972). Ishirô Honda was (more or less) finished with kaiju movies, and Nakajima’s principle director Eiji Tsuburaya had passed away in 1970. In the late sixties TV had finally invaded most Japanese homes, which hit the country’s movie industry hard. Some studios, like major player Nikkatsu, survived by going into soft-porn. Toho struggled on, but the atmosphere at the studio suffered due to major lay-offs. Movie budgets were slashed and with some exceptions, the quality of Toho’s kaiju films had been in decline since the mid-sixties. Nakajima simply didn’t have the enthusiasm for the work anymore.

Kenji Sahara, who had a couple of bit parts in Gojira, took over the role of the soft-cheeked romantic hero in Rodan (1956, review). He became one of the most recognisable faces in Toho’s science fiction films in the decades to come, playing both heroes and villains. His final Godzilla appearance came in 2004, in Godzilla: Final Wars. In 1966 Sahara played the lead in the first Ultraman series, Ultraman Q, and appeared in numerous subsequent Ultraman series. In 2008 he had cameo in Superior Ultraman 8 Brothers. As of February, 2024, Sahara is still in the books of the living, although now retired from acting.

Rodan was one of the very first on-screen appearances of 19-year-old Yumi Shirakawa, and her role as the ingenue in the film catapulted her to stardom, earning her the nickname “the Japanese Grace Kelly“. She became one of Ishiro Honda’s favourite actresses, and he cast her both in his tokusatsu (special effects) films and in drama movies. She played leads in The Mysterians (1957), The H-Man (1958), The Secret of the Telegian (1960) and Gorath (1962). Her best known role outside science fiction is in Yasujiro Ozu’s lauded drama The End of Summer (1961). She took a hiatus from screen acting in 1970, but made a successful comeback in 1981, mainly in TV, a career that lasted until 2014. Shirakawa passed away in 2016.

Yoshio Tsuchiya was something of a renaissance man. His father, a linguist who translated Shakespeare into Japanese, would read him the works of the English master as bedtime stories, so even though Tsuchiya got a degree in medicine, he followed his calling into theatre. Originally not keen on movie work, he was nonetheless persuaded by Akira Kurosawa to audition for the role of Farmer Rikichi in Seven Samurai (1954), and his audition was so powerful that Kurosawa reportedly nearly fell off his chair.

Tsuchiya went on to appear in nearly every Kurosawa film from 1954 onward. Thanks to Kurosawa, he also managed to get a rare tour of the sets of Gojira at Toho studios, filmed by Kurosawa’s good friend Ishiro Honda. Tsuchiya immediately became thrilled with the special effects works led by Tsuburaya, and he and Honda soon became great friends. He used to call Kurosawa and Honda ”his other two fathers”. Although fiercly protective of his actor, Kurosawa let Tsuchiya appear in all the sci-fi films he wanted to be in, as long as they could be worked around his own movie shoots.

He had a supporting role in Godzilla Raids Again (1955, review), and was slated for a leading role in The Mysterians (1957). He also appeared in Varan the Unbelievable (1958), The H-Man (1958), Battle in Outer Space, The Secret of the Telegian, The Human Vapor (1960), Matango (1963), Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965), Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965), The Killing Bottle (1967), Son of Godzilla (1967) Destroy All Monsters (1968), Space Amoeba (1970), Tokyo: The Last War (1989) and Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991). Tsuchiya was fluent in both English and French, rode motocross and played flamenco guitar. That is, besides being a medical doctor and one of Japan’s biggest movie stars.

The American scientists are played by Harold Conway and George Furness. Both were part of a small group of western expats, primarily Americans who stayed in the country after the American occupation, who found themeselves in high demand in the Japanese film industry. As there were few Caucasian actors working in Japan, movie studios drew upon the general expat community to fill roles of foreign diplomats, reporters, military personnel, scientists, businessmen and often villains.

Harold Conway was an American tax advisor and accountant, and one of the most prolific western actors in the country. He is best remembered for his quite prominent role in The Mysterians. While not necessarily a gifted actor (he’s the one with the “Good news, good news!” line), he was able to deliver Japanese lines quite convincingly. All in all, he appeared in over 60 films or TV shows from the 50s to the 70s. George Furness was one of the lawyers defending accused Japanese war criminals after WWII. He was able to get an acquittal for his client, making him a popular man in Japan. Furness appeared in 13 movies. Turkish-Japanese Enver Altenbay turns up briefly as a reporter in The Mysterians. He was the son of Turkish-Japanese journalist and occasional actor Jack Altenbay, who played the villain in Super Giant (1957, review).

Janne Wass

The Mysterians/地球防衛軍. 1957, Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Shigeru Kayama, Jijiro Okami, Takeshi Shimura. Starring: Kenji Sahara, Takashi Kimura, Yumi Shirakawa, Akihiko Hirata, Momoko Kochi, Susumu Fujita, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Minosuke Yamada, Yoshio Kusugi, Hisaya Ito, Harold Conway, George Furness, Enver Altenbay, Haruo Nakajima. Music: Akira Ifukube. Cinematography: Hajime Koizumi. Editing: Koichi Iwashita. Productin design: Teruaki Abe. Mogera design: Teizo Toshimitzu. Sound: Ichiro Minawa, Masanobo Miyazaki. Special effects director: Eiji Tsubiraya. Visual effects: Sadao Iizuka. Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka for Toho.

Leave a comment