A body-snatching alien infiltrates the international space program with intents at sabotage. Good low-budget effects and acting, but a dull script makes this one of Roger Corman’s lesser SF efforts. 4/10

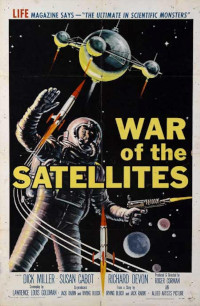

War of the Satellites. 1958, USA. Directed by Roger Corman. Written by Irving Block, Jack Rabin, Lawrence Goldman. Starring: Dick Miller, Susan Cabot, Richard Devon, Eric Sinclair, Michael Fox, Robert Shayne. Produced by Jack Rabin, Irving Block, Roger Corman. IMDb: 5.1/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

The United Nations-funded project Sigma under Dr. Pol Van Ponder, Van to his friends (Richard Devon) is in dire straits. Ten attempts at launching a manned “satellite” into space has ended in disaster, as they have all exploded upon contact with a mysterious “barrier”. For the 11th mission, Van volunteers himself. This is when a message arrives by rocket from space: humanity is a disease that must not infect the Universe. Therefore, all further attempts to reach outer space will be blocked by the Masters of the Spiral Nebula Ganna.

So begins Roger Corman’s 1958 movie War of the Satellites, one of the many films lobbed out by studios in the late 50s to take advantage of the hubbub around Sputnik, launched in October, 1957. This was Corman’s first SF movie for Allied Artists, his home away from American International Pictures, although it still starred a number of Corman’s favourites from his AIP pictures, including leads Richard Devon, Dick Miller and Susan Cabot. It was released as a double bill with Nathan Juran’s Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (review).

Delegates in the US bicker and argue about stopping the funding for the Sigma project, and to save it, Van takes it on himself to deliver an address to the General Assembly. But on his way by car to New York, he is attacked by some unseen force, and his car crashes and burns to a crisp. As news of Van Ponder’s death reaches the UN, the question is decided moot, as the project can’t go on without him, and no decision to cut funding is made. However, Van turns up in perfect health, despite having been declared dead at the site, offering up the suggestion that news about his crash must have been a misunderstanding. The project goes on, with support from Van’s colleagues, astronomer Dave Boyer (Dick Smith) and mathematician Sybil Carrington (Susan Cabot).

When the project goes on, the alien masters cause devastating natural disasters, and Van Ponder says he can do nothing else than give up – humanity is held hostage by an alien power, and says he won’t be bothered to bring the message to the UN, but sends Boyer to deliver it. However, Boyer agrees with Van Ponder’s boss Cole Hotchkiss (Robert Shayne) that the project should go on, and besides, he suspects that something is off with Van. Instead of delivering Van’s message, he launches into an inspiring sermon on the necessity on Mankind to find its own path and stand up to a universe of bullies. The funding for Sigma 11 is approved with standing ovations.

And something really is off with Van Ponder. It turns out that he is not Van Ponder at all, but an alien replica, capable of cloning himself to be at many places at once, and keeping in telepathic touch with his masters. While seemingly working diligently away at the Sigma project, he starts raising suspicions among some of his co-workers, not least Boyer, who realises that his body is perfectly and unhumanly symmetric. Boyer checks out his car, which seemingly stands unscratched in the parking lot, and finds an exact replica burned to a crisp at the scrap yard. Meanwhile technician John Compo (Jared Barclay) watch Van burn his hand to a crisp on a blowtorch without even noticing it. When he brings Dr. Lazar (Eric Sinclair), Van’s hand has mysteriously healed, and John is taken in for a psychiatric evaluation.

Despite the misgivings of Boyer and John, the crew of Sigma 11, consisting of three rockets which will bring three parts of the satellite into orbit, where it will be assembled, prepare for launch. The crew consists of Van Ponder, Boyer, Sybil Carrington, John Compo, Dr. Lazar and a few crew grunts. The new satellite will use a novel “solar radiation blast”, which they hope will catapult them through the “barrier” at the speed of light.

But when the satellite is assembled, John corners Van Ponder who reveals that he is an alien. He paralyses John with his mind and asks him to join him. When John refuses, Van kills him, and tells the others that John died during take-off. This leads to Dr. Lazar joining Boyer in his suspicions – as John was perfectly healthy before take-off. Boyer manages to get Ponder’s fingerprints, and shows Lazar and Sybil that each of the fingers have perfectly identical prints, which us humanly impossible. Lazar is on board, but Sybil laughs it off.

Lazar says he wondered why Van Ponder would never let him do a basic physical examination, and now insists on doing one, as he suspects that Van Ponder has no heart. Van Ponder agrees, but needs an hour to finish some tasks. During this time, he creates a heart for himself with the power of his mind, as to convince Lazar. Lazar still isn’t convinced, so Van kills him, and accuses Boyer of the murder, and has the crew confine him. However, having created himself a heart, Van has sealed his doom, as he now falls in love with Sybil. He traps Sybil in the solar radiation room and tries to convince her to become one of his race so that she can survive the destruction of the satellite. Meanwhile, Boyer overpowers his guards. Van clones himself and one of his copies goes after Boyer, while the other tries to force Sybil into submission. In between, he tells the crew by radio to override the plan to blast off into space, and instead head with a steady pace straight toward the barrier, which would mean certain death. Van 2 catches up with Boyer, believing he is still invulnerable to harm. But having created himself a heart has made him “human”, and Boyer shoots him to death. When Van 2 dies, Van 1, in the room with Sybil, also perishes. Boyer then orders the crew to proceed to light speed and go through with the original plan. The plan succeeds, and Boyer reports to Earth control: “We are passing through Andromeda at the speed of light. We’ve made it. The whole universe is our new frontier!”

Background & Analysis

That’s an unusually detailed plot synopsis from me, but it feels that as so little actually happens in this film, what does happen must be rendered in detail for any analysis to make sense to the reader. I hope you’re still with me.

As stated above, the launch of Sputnik gave rise to a small cottage industry of satellite-themed movies, and even movies that were not really about satellites were made to be about satellites. For example Allied Artists’ companion piece to War of the Satellites, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, insists on calling an alien spaceship a “satellite”. The Flame Barrier (1958, review), released just a few weeks earlier, also involved a satellite.

According to Roger Corman, it was producer/writer/special effects wizard Jack Rabin who suggested to him a movie about satellites. Corman then took the idea to Allied Artists. In a 2019 interview, Corman recalled his meeting with Steve Broidy of Allied Artists: “I said, ‘Steve, if you can give me $80,000, I will have a picture about satellites ready to go into the theaters in 90 days.’ And then he said, ‘What’s the story?’ And I said, ‘I have no idea, but I will have the picture ready.’ And he said, ‘Done.’ And he gave me the money.” Jack Rabin and Irving Block are credited for the story, but it was Lawrence Goldman who put toghether the script.

Corman has said War of the Satellites was one of the fastest productions he ever did, and that the whole process, from scriptwriting to release, took only eight weeks. Publicity and theatre dates were ready and booked even before the script was done. Goldman spent two weeks on the script, and Corman got a 10-day shooting schedule, which he finisned in eight. Both Corman and Rabin have made it sound as if the movie came out just weeks after Sputnik was launched, but that’s certainly not the case. Sputnik was launched in October 1957 and War of the Satellites premiered in April 1958.

Most of the movie is filmed in nondescript rooms and hallways, but it doesn’t feel cramped. The “satellite” feels impossibly roomy, more like a Death Star than what an actual space station is like, with large rooms and long hallways. You get the feeling of a labyrinthine space where it would be easy to get lost. In reality, Dick Miller said, the halls were simply made up of four arches that ended in a wall, at which you had to make a turn. The arches could be spaced differently to create long or short hallways. Richard Devon said the sets were “practically nonexistent” and “could be folded up in a matchbox”. It’s a typically minimal Cormanesque solution, and it works surprisingly well. The instruments on the “satellite” are your typical wooden panels with gauges, lights and buttons that were seen in every space movie of the 50s. One rather impressive piece of scenography are the reclining seats, that look rather futuristic and that sort of slide into position by just a push of a button. In fact, these were just over-the-counter reclining chairs.

Jack Rabin, Irving Block and Loius DeWitt were a crack team of low-budget visual effects artists that almost always elevated any cheap movie they worked on. Their work in War of the Satellites are amongst their best. An impressive backdrop of the three rockets in the first half of the movie, most likely painted by Block, lends the film a bit of scale and even realism. The scene in which the satellite seemingly automatically assembles itself is quite good, even if the satellite itself looks quite miniaturesque. The scenes of Van Ponder duplicating himself are very good double exposure shots that seem to belong in a much classier movie. The effects really are impressive considering the film’s minuscule budgets. With the exception of George Pal’s big-budget epics and Forbidden Planet (1956, review), few space movies of the 50s sported significantly better effects that War of the Satellites. Granted, the effects are limited in scope and the “satellite” effects are all miniatures.

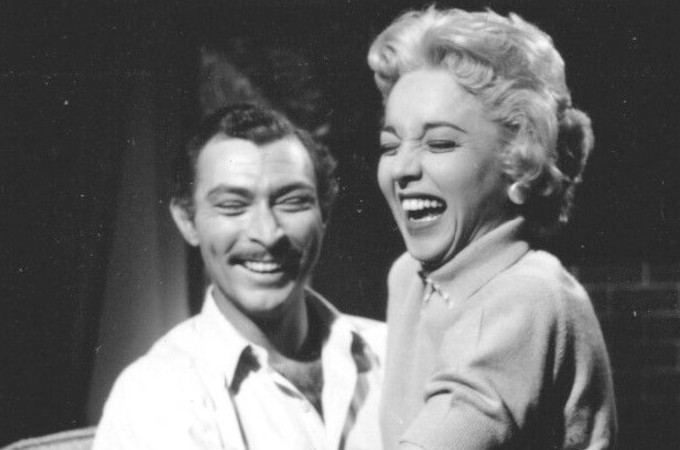

As always in Roger Corman’s films, the acting ranges from decent to good. Richard Devon complains to Tom Weaver that he was so often cast as villains, as he had a pencheant for comedy, which he rarely got to show. But comedy and villainy, I find, often go hand in hand, and most good movie villains tend to have a feel for comedy. Maybe cracking the code of balancing the sincere with the hammy loftiness that many good villains have require the kind of distancing that good comedy actors are capable of. And of course, delivering the purple punchlines that often go with villains requires impeccable timing. Anyway, Devon balances the dual role of Good Van Ponder and Evil Van Ponder very nicely. Devon also said he enjoyed this particular acting challenge, stating that it was one of his best roles in a Corman movie. Dick Miller, a Corman staple whose roles had gradually grown over the years, was now asked to step into the boots of the macho hero, a task the diminutive actor didn’t take on without some intrepidation. In an interview, he said he felt he was too small to play the hero, and was miscast, especially when he had to take on the over 6-foot tall Devon in a fisticuff. Miller was more at home as a wise-cracking weirdo, but his performance in War of the Satellites proves that he had range beyond his usual quirky characters. Despite his misgivings, he strikes a good hero – he was reasonably handsome, had good physicality and good dramatic acting chops as well. He plays the role sincerely and with conviction. Susan Cabot was another actor who was really beyond the low-budget fare that she got stuck in with Corman (she had a decent career going with Universal, until she got tired of playing gun molls and damsels in distress). As Bill Warren points out, she is believable as a scientist in War of the Satellites, something which was not nearly always the case with the leading ladies in these films.

The lighting is flat and uninteresting, and the direction has little flair or interest. The takes are long, which is classic Corman, but he us usually able to bring a surprising amount of dynamism through moving camera and through the way he moves his actors through the frame. There is little of this low-budget creativity in War of the Satellites, perhaps stemming from the restrictions of the “non-existent” sets: it is an unusual Corman movie inasmuch that it is almost entirely studio-bound. That said, the film moves along at a good clip, and despite doing sometimes long takes – and notoriously seldom doing a second take – the director keeps things lively and, for the most part, entertaining.

The weakest part of War of the Satellites is the script. That’s too bad, because there are ideas here that could have been mined – not least the self-replicating alien, quite possibly a first on the movie screen. But screenwriter Goldman isn’t able to work this potentially intriguing feature into the story in any meaningful way. For example, after Van creates a heart for himself, there would have been a superb opportunity for a yin/yang situation, a Jekyll/Hyde turn of events, but the script never goes for this obvious climax. Whether or not this is indeed a film about satellites is difficult to determine. It seems Goldman, and a lot of other B-movie screenwriters of the late 50s didn’t quite understand the difference between a satellite and a rocket, or they just didn’t care. Here, the UN has in fact been successful in placing a satellite in orbit 10 times, before it has struck the “barrier” as it has ventured to go further into space. But satellites don’t venture further into space. In the end, Sigma 11 travels to the Andromeda Galaxy at the speed of light, most definitely making it a spaceship and not a satellite.

Technicalities aside, there is much in the script that doesn’t quite make sense from a logical standpoint. Primarily: why do the aliens go along with the charade of the Sigma 11 launch in the first place? Unlike films like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), or even low-budget fare like The 27th Day (1957, review), the aliens don’t interfere to test humanity or teach us a lesson. They see us as a disease that they don’t want infecting the galaxy, and thus their only objective is to prevent us from conducting space exploration, end of story. The aliens have proven they are perfectly cabable of doing pretty much what they want on Earth. They have the power to cause natural disasters and car crashes, to take body-snatch humans, kill them with a tought and replicate themselves ad infinitum. Surely they have several means of just stopping the launch from taking place. In fact, had they just killed Van Ponder instead of replicating him, the Sigma project would have been cancelled. Or: why all the cloak-and-dagger stuff? Alien Van Ponder could have just killed everyone on the satellite and ensured its destruction, instead of going through all the trouble of trying to blend in. If nothing else, this puts severe strain on the aliens’ claims of “superior intelligence”.

Then there’s stuff that’s just plain silly, like Alien Van Ponder falling in love with Sybil after creating a heart for himself. Van Ponder wasn’t interested in Sybil before he became an alien, and afterwards he has barely had any interaction with her. The idea of a hostile alien spending time with humans and learning to appreciate and love them is a perfectly fine trope, but that’s not what happens here. Alien Van Ponder just falls in love with Sybil, but still hasn’t changed his mind about humanity. Plus, of course, the obvious: the heart is not a love machine, it’s a blood-pumping muscle. As an aside, Richard Devon said he struggled somewhat with the scene in which he was to create a heart for himself, as the script gave no indication as to how this action was to be illustrated. The direction from Corman reportedly was: “Do something, Richard!”.

As I’ve written before, there was a curious tendency in late 50s science fiction films to use the cold war tropes of genre movies of the earlier part of the decade and draining them of ideological substance. The visiting alien trope of The Day the Earth Stood Still was created to shine a light on human politics and co-existence, the good and the bad, and stood as a sort of representation of the ideals of the United Nations – a pacifist figure looking with both amusement and terror at the childish wars of the human race. The Klaatu clone of The Strange World of Planet X (1958, review), however, has little interest in reforming the human race. He simply wants to restore the balance of Earth’s magnetic field that the aliens use as UFO highways. Giant radioactive monsters like Godzilla were once powerful symbols of the devastation of nuclear war and metaphors for cold war armament. In the late 50s giant monster were just giant monsters, conjured up as entertainment for drive-in audiences. The prominent role of the UN in War of the Satellites is perhaps the closest the movie gets to any sort of social or political message. The US, for example, didn’t demilitarise its space exploration until later in 1958. One can perhaps draw parallels between the aliens and the Russians, as illustrated by John’s retort to Alien Van Ponder: “I was born a human and I’ll die one before I join a race that kills innocent people for abstract ideas!” But on the other hand, it sounds more like an objection to all forms of fanaticism, something which the US certainly wasn’t devoid of either during the McCarthy years. However, Lawrence Goldman doesn’t seem to have made any conscious effort of infuse the movie with a coherent cold war commentary.

The main problem with the script of War of the Satellites is that it never gets around exploring the interesting themes it does set up. You don’t sense any passion for exploring space, and space itself is merely represented by a black background for the miniature models to be filmed against. Humanity is accused of being a plague upon the universe, but no-one ever ponders what may have given the aliens that idea, there is no Earthly introspection and no redemption. Neither does the script give the aliens any chance to change their opinion about humans (which raises the question: what happens after the end of the film? Sure, humans broke through the barrier, but the aliens haven’t gone anywhere, have they? They can still just as easily wipe out humanity if they so please). No ideas are discussed, there are no real character arcs and all the characters are cardboard cutouts devoid of any peronalities. The plot, while lined with science fiction paraphernalia, is just a simple cloak-and-dagger potboiler borrowing its outline from spy films of yore.

Nevertheless, Roger Corman seldom made really bad films, and War of the Satellites bears the Corman stamp of – well, quality isn’t the right word, but let’s say “adequacy”. It’s certainly not one of his better 50s SF movies, but it’s a competently made, breezy, entertaining 65 minutes with some good acting and surprisingly well-realised low-budget effects. All in all, this is a routine programmer, interesting for completists mainly for featuring what is probably movie history’s first self-replicating alien menace.

Reception & Legacy

War of the Satellites was co-released by Allied Artists as a double bill with Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, a movie that has left a significantly larger footprint in movie history than this one. I haven’t seen numbers, but it was by all accounts a very succesful double bill.

The reviews in the trade press were forgiving of the film’s flaws. The often over-enthusiastic Motion Picture Daily called it “a compact, dramatically compelling treatment”. Harrison’s Reports wrote: “The story, aside from being fantastic, is somewhat rambling and confusing. It should, however, squeeze by with undiscriminating audiences, for the direction and acting are fair and there is some suspense in waiting for what will happen because of the disobedience of the Earthians.”

Variety was less forgiving, calling the film “a lesser entry for the exploitation market”. According to critic “Whit“, the film featured an “over-talkative script […] leaving audience unenlightened through most of film’s rambling unfoldment”. He continued: “Characters are so unreal they are mere walk-throughs”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy echoed Variety’s review: “The signs of swift making are all too evident especially in the over-talkative script and the mis-match between special effects and the action”. Bill Warren in Keep Watching the Skies! was slightly more positive: “War of the Satellites is essentially just another mediocre space movie made to cash in on a fad, but som good model work, decent performances and smooth, quick direction keep it watchable throughout”.

Today the film has a 5.1/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on 1,200 votes, and a 2.9/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on a little more than 700 votes.

Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings gives the film a mildly positive review: “It’s movies like this that make me really appreciate Roger Corman. Had anybody else tried to make an outer space epic like this on an Allied Artists budget, it would have probably been dull and laughable. Corman doesn’t turn it into a classic, but he manages to keep it from being a waste of time, and except for the fact that the middle of the movie sags a little, he keeps the interest level up. He’s helped by a likable and familiar cast; in particular, it’s really a lot of fun seeing Dick Miller in a rare leading role.” Richard Scheib at Moria follows suit with a 2.5/5 star review: “War of the Satellites is an average Roger Corman film. It disguises itself well and doesn’t look that cheap, despite using a series of terrestrial hallways and rooms to represent on board the ships. On the other hand, there is not the quirkiness to it that lifted other similar Corman works of this era like It Conquered the Word, Not Of This Earth and Attack of the Crab Monsters.”

Cast & Crew

I’m writing this just a few days after the death of cinematic genius Roger Corman. As critic Robin Bailes puts it, the news of Corman’s death was at the same time both predictable and shocking. Predictable, as the man was 98 years of age, but shocking, as “it seemed so out of character, at 98 he was still working, still making movies, it just didn’t seem like he was going to be able to find the time to die”.

I’d love to write a longer obituary on Roger Corman, but the sheer wealth of his production makes it impossible to do here, and would take weeks for me to write. The self-taught maverick turned in his first Hollywood script in 1954, directed his first movie in 1955 and produced his last film in 2021. Corman directed over 50 movies – that feat that alone would make him one of the most prolific filmmakers in Hollywood. But he also produced close to 500 feature films, surely more than any other producer in the history of filmmaking, by a fairly wide margin. When he needed a break from his hectic pace, he started his own distribution company, which was responsible for bringing to the US audience such directors as Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, Francois Truffaut and Werner Herzog.

As a director, Corman was primarily active from the mid-50s to the early 70s. At AIP, he was one of the first to tap into the growing teen market with cheap street racing, science fiction and horror movies (although he cut his teeth, as so many filmmakers, with westerns), and in the 60s made his seven-film Edgar Allan Poe cycle, primarily at Allied Artists. It was these films that secured his reputation as an auteur and caught the interest of major studios, but also cemented Vincent Price as a horror icon. The late 60s saw him tap into yet another cultural trend long before the majors – the biker movie, one of which starred Dennis Hopper, who went on to direct Easy Rider in 1969, starring in it with another Corman alumni, Jack Nicholson. After a couple of flirtations with major studios, which left him with a bad taste, Corman abandoned directing in the mid-70s.

The legacy of Corman looms gigantic, even if most of his films are probably too obscure for most mainstream audiences to have ever encountered them. But all of today’s pop culture consumers recognise such franchises as Grand Theft Auto, The Fast and the Furious and Death Race 2000, all of which Corman is – in one way or the other – responsible for. Corman is also almost solely responsible for the resurgence in popularity the works of Edgar Allan Poe in the 60s, turning him from an academically revered author and poet into a household name once again. And now I have not even mentioned Little Shop of Horrors, a brilliantly bizarre horror comedy shot in only three days in 1961 on leftover sets from another movie (a tactic the penny-stretching Corman used on several occasions), that has turned into an 80s big-budget remake and an award-winning stage musical. Nor have I mentioned all the actors and directors that went through “the school of Corman” as some of their very first Hollywood jobs, such as the afore-mentioned Hopper and Nicholson, as well as Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Peter Bogdanovich, David Carradine, Charles Bronson and many, many more.

Corman was never an actors’ director, nor was he really a great visualist (although his Poe films show that he did have a keen eye for visuals, when he wanted to employ it). But Corman always tried to work from a good and, if possible, original idea, which is what set much of his 50s and early 70s output apart from the rest of the exploitation field. And when he had the chance, he would employ good, intelligent and quirky writers. His go-to writer for his early low-budget films was Charles Griffith, a writer who would not always turn in Oscar-worthy scripts, but whose far-flung, original ideas continuosly brought fresh takes on whichever genre he was working in. On many of his Poe films, he would work with renowned author and screenwriter Richard Matheson.

There is no filmmaker in Hollywood that Roger Corman can be compared with. As opposed to many of the exploitation and low-budget “schlock masters” that have styled themselves as Cormanesque, Roger Corman had genuine talent for direction and production, which is visible even in his most risible films. Corman made films in circumstances that should have been impossible, and often the low budgets and the short shooting schedules did show up on screen. But a Corman film always bore a certain quality stamp – be it a strong script, great actors or just the fact that Corman knew how to shoot a movie on a dime without it looking like it was shot on a dime. While many actors have complained about Corman’s lack of direction and poor handling (that is, non-existing handling) of actors, the producer had an unfailing talent of spotting good actors that were willing to work for union minimum, and that were able to, essentially, direct themselves. When Griffith’s script, Corman’s direction and the quality of the actors all aligned, moments of pure genius could sometimes appear. See for example the exemplary work done by Lee Van Cleef, Peter Graves and Beverly Garland in It Conquered the World (1956, review) – or Garland, Jonathan Haze and Paul Birch in Not of This Earth (1957, review).

Corman has always been the first to admit that many of his films are of questionable artistic value, and for him, the most important thing was to make films, not necessarily to make art. But he was also fiercely protective of his independence, and insisted on making his films the way that he wanted to make them, which is why his flirt with mainstream cinema was brief and unhappy. But while Corman always prided himself on his ability to make movies fast and cheap, and while he was always the consummate entertainer and exploitation specialist, at the heart of almost all of his films is the notion that they are about something. This, especially, is was make his 50s science fiction effort stand out so clearly against those of his competitors’. There’s always a feeling that wedged in between the latex monsters and cardboard sets, there is an effort to say something. It may not always be eloquent, well formulated or original, but it’s always there.

Corman seldom got to make the movies that he really wanted to make – there are exceptions, his Poe cycle, his 1962 anti-racism drama The Intruder, starring William Shatner, perhaps his biker pictures. This was partly a result of his fierce protection of his independence, but also of his business-minded approach to filmmaking: he knew that the films he wanted to make would not make a profit. And most of all, one gets a feeling that the most important thing to Corman was simply making films.

I can say with confidence that there will never be another Roger Corman. The Hollywood that spawned him doesn’t exist, hasn’t existed in five-six decades. One can also argue that Corman has done rather little of note quality-wise – despite churning out hundreds of films – since producing cult classics like Android (1982), Chopping Mall (1986) and Watchers (1988). There were hardly any masterpieces left for Corman to make in the 2020s, and his N:th “Sharktogator vs. Tigerwerewolf” wouldn’t leave any great void in cinema history, had it never been made. Nevertheless, the loss of this B-movie icon feels like the definitive end of an era, in our age of streamlined CGI blockbusters, all pandering to the smallest common denomitator, produced by risk-averse studios more interested in counting their profits than taking risks on interesting projects. Corman was appalled at the state of Hollywood today, a bloated mega-industry dominated by a handful of powerful studios and streaming services. In the 50s, when he set out to prove that all you needed to make a film was a script, a camera and a few actors, he couldn’t have imagined today’s movie industry in his darkest nightmares.

Corman has been criticised, from time to time, of taking advantage of his cast and crew, paying them minimum and having them work long, arduous shoots with little regards to health and safety, often pinching pennies whereever he could. Members of his close-knit team in the 50s and early 60s have also complained that when Corman moved on to greener pastures, he left his old, loyal family behind. An exception was Richard “Dick” Miller, who was one of Corman’s favourites and appeared in almost all of his early movies, mostly in small walk-on parts that still remained some of the most memorable in the movies.

New Yorker Dick Miller, born in 1928, had a PhD in psychology, worked at a hospital and performed on Broadway, nurturing hopes for a career in writing. He moved to Hollywood in 1952, hoping to launch a career as a screenwriter. However, he was noticed by Roger Corman not for his writing but for his acting chops, and made his debut in small roles in three of Roger Corman’s very first movies, all westerns. From 1955 to 1963, Miller appeared almost exclusively in Roger Corman movies, mostly in small, memorable roles as the vacuum salesman in Not of This Earth (1957). Miller thought himself too short to play leads, but nevertheless, he was handsome enough and physical enough to pull off leads in action and horror movies, and definitely had the acting chops, so Corman cast in him as the lead in two of his movies, War of the Satellites in 1957 (as a hero) and A Bucket of Blood in 1959 (as a villain). Another noteworthy early Corman role was that of the flower-eating Vurson Fouch in Little Shop of Horrors (1960).

By 1963 other directors were taking note of Miller’s knack as a character bit-part player, and by the 70s, he started to get regularly cast by many of Corman’s old alumni and fans, such as Robert Aldrich, Jonathan Kaplan, Jonathan Demme, Joe Dante, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, Allan Arkush and James Cameron. He also continued to work with Corman, in films like The Wild Angels (1966), The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967), Death Race 2000 (1975). Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1979), Smokey Bites the Dust (1981) and Chopping Mall (1986). Outside his work for Corman, he is probably best known for his roles as a Buck Gardner in Piranha (1978) and an occult book shop owner in The Howling (1981) – both directed by Joe Dante, the gun store owner who gets blasted by Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator (1984), and as Murray Futterman in Gremlins (1984) and Gremlins 2 (1990) – the war veteran who rants about foreigners putting gremlins in the machines, thus justifying the original film’s title. All in all, Miller appeared in 21 science fiction films between 1955 and 2007. Aside from the above mentioned, one can name, for example, Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), Explorers (1985), Night of the Creeps (1986), Project X (1987), Innerspace (1987) and Small Soldiers (1998). He also appeared on Star Trek: The Next Generation (1988) and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1995). In the latter, he played the officer who interviews Sisko, Bashir and Dax after they arrive in San Francisco in the 21th century. Miller passed away in 2019.

The villain of War of the Satellites, Richard Devon, was another actor in the early Roger Corman stock company. According to himself, in an interview with Tom Weaver, Corman liked him because he was able to work at the hectic pace the director/producer demanded, he never flubbed his lines, and he was able to keep his head cool when things didn’t go according to plan. Corman provided Devon with his largest movie parts, playing the Devil in The Undead (1957) and the alien in War of the Satellites (1957). Most of his career was spent doing guest bits on numerous TV shows, including a recurring role in Yancy Derringer. He had a successful career as a character actor from the mid-50s to the late 80s. Devon started his SF career with a recurring role in the TV series Space Patrol in 1954, and appeared in the science fiction movies War of the Satellites (1958) and The Silencers (1966). He appeared in over half a dozen SF TV shows, including one episode of The Planet of the Apes (1974) and a recurring role as a voice actor on Star Wars: Ewoks (1986).

Lead actress Susan Cabot is primarily remembered for two things: having starred in six Roger Corman movies, and being bludgeoned to death by her own son, who was fathered by King Hussein of Jordan. A multi-gifted artist, Cabot studied music and art before complementing her income with TV work at a local New York TV station. She was spotted by an agent for Columbia, which took her to Hollywood in 1950, where she signed a contract with Universal. She gained some recognition in the lead of a string of B-movies, primarily westerns, but tired at the roles she was being offered, broke off her contract in 1954 and returned to resume her studies in art. However, she was reeled back in to Hollywood by Roger Corman in 1957, and starred in six Corman films in three years: Carnival Rock (1957), Sorority Girl (1957), The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent (1957), War of the Satellites (1958), Machine Gun Kelly (1959) and The Wasp Woman (1959). To Tom Weaver Cabot said that she enjoyed the off-beat characters and the artistic freedom that Corman provided her with.

In 1959 Cabot entered a highly publicized affair with King Hussein of Jordan, which produced a son in 1964, although at the time, the father was kept secret. In 1986, Cabot was bludgeoned to death in her home by her son, who claimed that she had attacked him with a scalpel and a bar bell due to substance abuse and mental illness. Cabot, herself a victim of a trying childhood and abuse, had for years suffered a wide range of mental problems. The son was charged with involuntary manslaughter and probation.

The rest of the cast is made up of workhorse bit-part players, many of whom had most of their biggest roles in Roger Corman’s films. Michael Fox, playing the main naysayer, is a real science fiction fixture, whom we encountered on this blog on a number of occasions. He appeared in Killer Ape (1953), The Magnetic Monster (1953, review), The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), Riders to the Stars (1953, review), Gog (1954, review), War of the Satellites (1958), The Misadventures of Merlin Jones (1964), as well as the TV series Science Fiction Theatre, Adventures of Superman, The Twilight Zone (both the original and the remake), My Favorite Martian, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, The Wild Wild West, Lost in Space, Batman, Gemini Man, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, Voyagers! and Knight Rider.

Robert Shayne had a long and prolific career on stage, in film and TV, without ever becoming neither Broadway nor Hollywood nobility. He had a string of supporting roles in A films in the forties, notably opposite Bette Davis in Mr. Skeffington (1944) and Barbara Stanwyck in Christmas in Connecticut (1945), and is sometimes remembered for his brief turn opposite Cary Grant in North by Northwest (1959). More often, however, he was cast in small, prominent or even leading roles in B movies, such as The Spirit of West Point (1947), sometimes described as the worst sports movie ever made.

Shayne is best known for appearing as Inspector Henderson in the TV-series Adventures of Superman (1952-1958). He appeared in numerous sci-fi films, such as Invaders from Mars (1953), The Neanderthal Man (1953, review), in which he actually played the lead, Tobor the Great (1954, review), Indestructible Man (1956, review), The Giant Claw (1957), Kronos (1957), How to Make a Monster (1958, review), The Lost Missile (1958, review), Teenage Cave Man (1958, review) and Son of Flubber (1963). In the sixties and seventies he was mainly seen on stage and on TV, and he practically retired in 1977 after nearly 50 years in the film business. He made a brief comeback in 1990-1991, then 90 years old, in two episodes of the TV series The Flash, as a newsstand salesman. He was actually blind at the time, and learned his lines by having his wife read them out for him.

This is also our first encounter on this blog with the legendary Bruno VeSota, who had a long and prolific career as a character and bit-part player both in film and TV, as well as a large body of work in radio. We’ll dig further into the life and crimes of Mr. VeSota at a later time – suffice to say that alongside his small but sometimes memorable film and TV appearances, he is best known for directing three schlock movies: Female Jungle (1955), The Brain Eaters (1958, review) and Invasion of the Star Creatures (1962).

Then there’s comedienne, actress and writer Mitzi MacCall, with a long and varied credit list including everything from Flintstones to Crimson Peak. Eric Sinclair, turning in a good performance as Dr. Lazar, was a busy bit-part player during the 50s and 60s, who also appeared in Corman’s The Cremators (1972) and John Landis’ Schlock (1973).

And then, of course, there’s Roy Gordon, another bit-part player whom Corman and other low-budget SF producers awarded with larger than usual roles – in War of the Satellites (1958) he plays the US president. He also appeared in The Unearthly (1957, review), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958, review), War of the Colossal Beast (1958, review), The Wasp Woman (1959) and Hand of Death (1962), always playing some sort of authority figure.

Irving Block and Jack Rabin are unsung heroes of low-budget SF, often working with Louis DeWitt on special effects, writing and producing. Rabin and Block had started their sci-fi collaboration on Rocketship X-M, with Kurt Neumann and Karl Struss, and continued on Flight to Mars (1951, review), and would go on to become B movie legends in the fifties. They went on to collaborate on Unknown World (1953, review), Invaders from Mars, World Without End (1954, review), Monster from Green Hell (review), The Invisible Boy, Kronos (both 1957), War of the Satellites (1958), The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959) and Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review). Both also worked on a number of other sci-fi films separately. Rabin worked on movies including The Man from Planet X, Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), Robot Monster (1953, review), Deathsport (1978) and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Block did work on films like Captive Women (1952, review), Forbidden Planet (1956, review) and The Atomic Submarine (1959).

Janne Wass

War of the Satellites. 1958, USA. Directed by Roger Corman. Written by Irving Block, Jack Rabin, Lawrence Goldman. Starring: Dick Miller, Susan Cabot, Richard Devon, Eric Sinclair, Michael Fox, Robert Shayne, Jered Barclay, John Brinkley, Tony Miller, Bruno VeSota, Jay Sayer, Mitzi McCall, Roy Gordon, Beach Dickerson, Jim Knight. Music: Walter Greene. Cinematography: Floyd Crosby. Editing: Irene Morra. Art direction: Daniel Haller. Makeup: Stanley Orr. Sound: Philip Mitchell. Special effects: Jack Rabin, Irving Block, Louis DeWitt. Produced by Jack Rabin, Irving Block, Roger Corman for Allied Artists.

Leave a reply to Janne Wass Cancel reply