What caused Mrs. Delambre to kill her husband in a steel press? And why is she obsessed with flies? Vincent Price ponders these questions in Fox’s 1958 classic, a traditional mad scientist tale, but enhanced by an unusually engaging script. 7/10

The Fly. 1958, USA. Directed by Kurt Neumann. Written by James Clavell. Based on the short story The Fly by George Langelaan. Starring: David Hedison, Patricia Owens, Vincent Price.Produced by Kurt Neumann. IMDb: 7.1/10. Letterboxd: 3.5/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 7.0/10. Metacritic: 62/100.

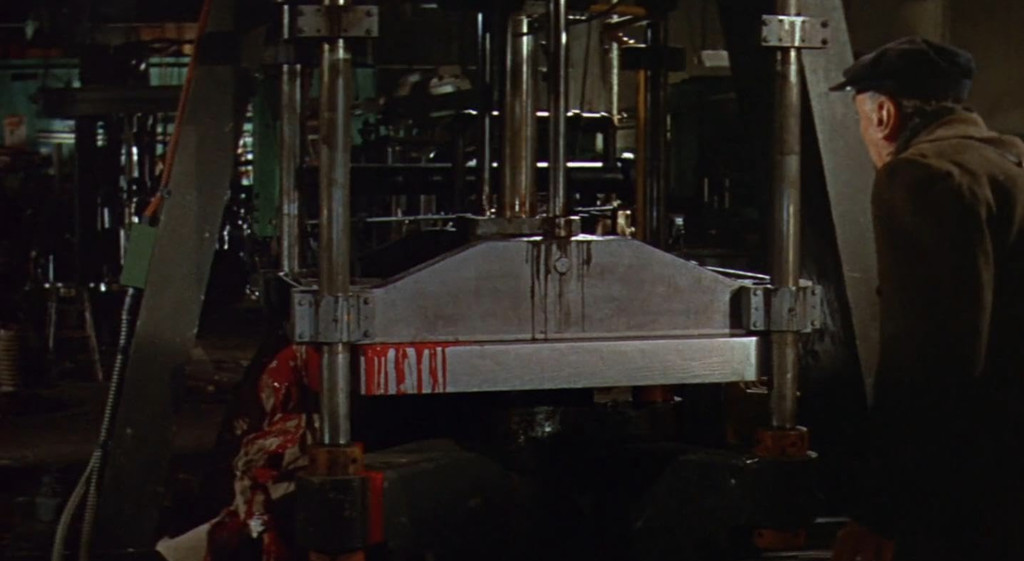

One night in Montreal, steel manufacturer François Delambre (Vincent Price) gets a call from his sister-in-law, Helene (Patricia Owens), who says that she has killed her husband, Andre. In her own words, she has crushed his head and arm in a hydraulic press at the steel plant. Her story is corroborated by the nightwatchman (Torben Meyer), who has seen her leave the scene of the crime. When François and inspector Charas (Herbert Marshall) visit the plant, they find the remains of Andre just as Helene has described. When Helene is interrogated by Charas, she readily admits to her crime, but refuses to give an explanation for her actions. She reports that she and her husband were perfectly happy and very much in love, but that she killed him nevertheless, and does not regret it. Beleiving her out of her mind, Charas confines her to bed rest at her house while the investigation proceeds. Helene does not seem particularly upset with her fate, until her nurse (Betty Lou Gerson) kills a house fly. Helene protests wildly and burts into uncontrollable tears, but inspecting the cadaver, is relieved when she sees that it is “just an ordinary fly”.

So begins Regal Films’ and 20th Century Fox’s science fiction classic The Fly (1958). Significantly higher budgeted than most late 50s SF movies, the film was shot in CinemaScope and colour. Based on George Langelaan’s short story, it was very faithfully adapted by James Clavell, who is very much the man of the hour today, as it is his novel that the lauded streaming show Shogun is based upon. The Fly was directed by Kurt Neumann, who had made a handful of very decent SF movies in the past. However, The Fly will remain the film he is remembered for – it’s a bona fide classic, and whether praised or derieded, one that has left a permanent mark on movie history.

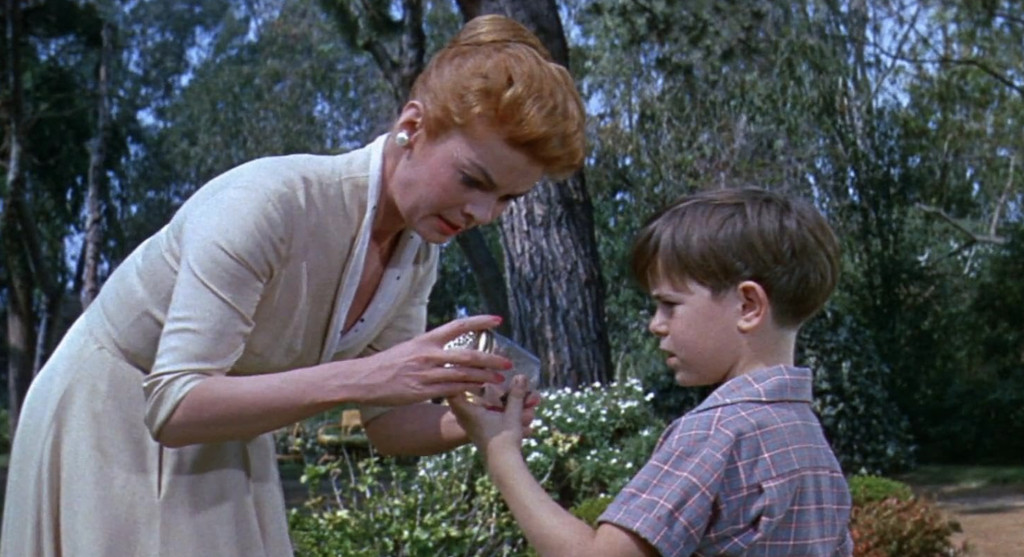

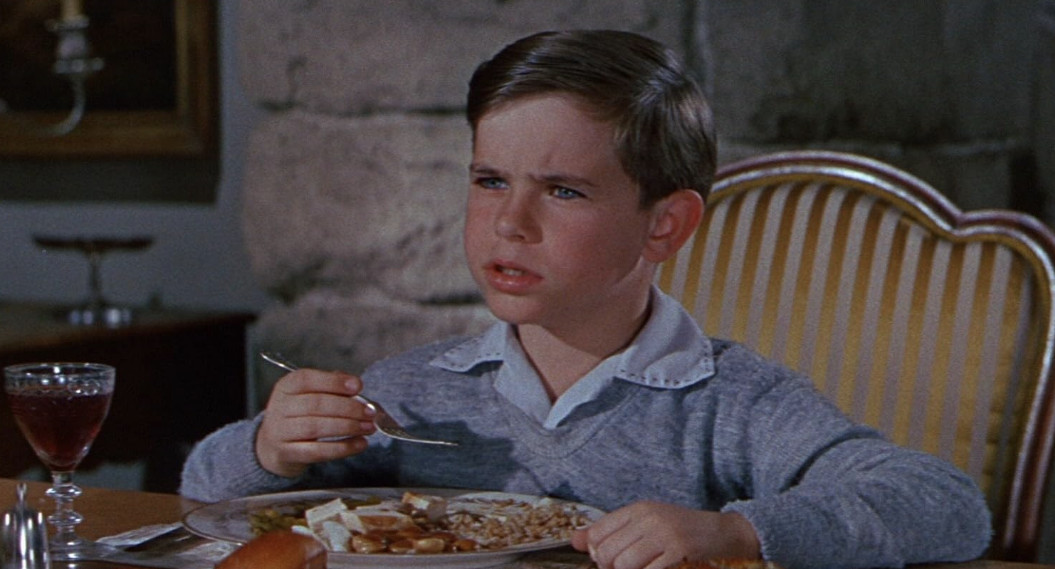

François is made guardian of Helene’s and Andre’s son Philippe (Charles Herbert) while mom is “sick”, aided by housekeeper Emma (Kathleen Freeman). One day, Philippe asks François in earnerst “How long do flies live?”, and tells him that he saw the fly that mom had been looking for, the one with the white head, in François’ study. François’ suspicions are raised as he connects Philippe’s question with Helene’s obsession with flies. The next day, he confronts Helene, lying to her that he is in possession of the strange fly, and threatens to give it to inspector Charas, unless she tells him why she killed Andre. Helene relents, but will give her story only if Charas is also present. Said and done, the three gather by Helene’s bed, and she begins unfolding her morbid tale.

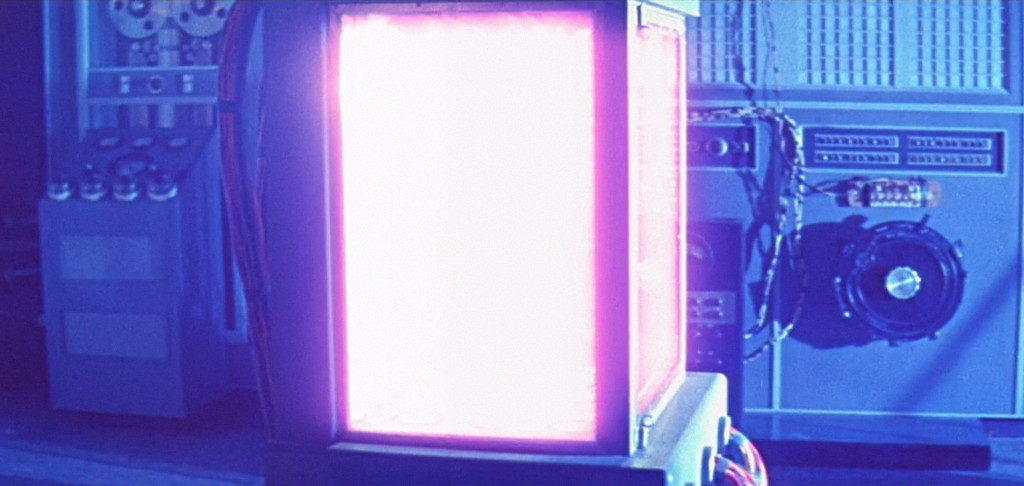

The second act in the movie is all told as one long, coherent flashback, beginning with Helene recounting her and Andre’s happy, loving life with each other in their idyllic house, in which Andre, a brilliant scientist, works long hours in his basement lab. While working on an idea of a flat screen TV, Andre has had an idea of an “disintregrator-reintegrator”, or in SF tems, a teleportation machine. The idea, he explains, is the same as with TV: the tube disintegrates an image and reintegrates it on the screen: why should the same not be possible with atoms? After some trial and error (like disintegrating the family cat and failing to reintegrate it), Andre finally manages to teleport a guinea pig, and celebrates with Helene by teleporting a bottle of champagne. They invite François over to join the celebrations, but when Helene brings him to the basement, they are met by a note on the laboratory door: “Do not disturb. I am working”. They both laugh it off as being typical of Andre, always engulfed in his work. Later in the day, the son Philippe brings Helene a strange fly he has found, one with a “white head and a sort of funny leg”. Helene tells him to let the fly go.

When Helene returns to the lab in the evening, she is met again by a locked door, and a note informing her that Andre has had an accident, and can’t talk. He is in “no immediate danger, even though it is a matter of life and death”, and instructs Helene to knock three times if she understands, and then fetch him a bowl of milk laced with rum. Helene obliges, and is instructed to enter the lab, walk straight to the table and set down the milk, not look at Andre, and then look for a fly in the reintegrator booth – a fly with a white head. Andre observes all this in silence, his head covered with a black cloth, and his left hand buried in his lab coat pocket. Helene doesn’t find the fly, as she knows she wont, because she had Philippe set it free. But she promises to look for it tomorrow.

Distraught, but determined to help Andre, Helene sets about catching the fly with Philippe and housekeeper Emma, without telling them why. At one point they nearly have it, but it escapes through a broken window. Later the next evening, after fruitless efforts, Helene again visits Andre, who tells her (via note) that he had a mishap when trying to teleport himself, and didn’t notice a fly that had also entered the disintegrator. She later catches Andre off guard and pulls the cloth off his face – revealing that Andre now has the head and left arm of a fly! The image switches to Andre’s point of view through his compound eye – showing a grid work of dozens of images of Helene screaming in dispair – adding one iconic shot directly after the other.

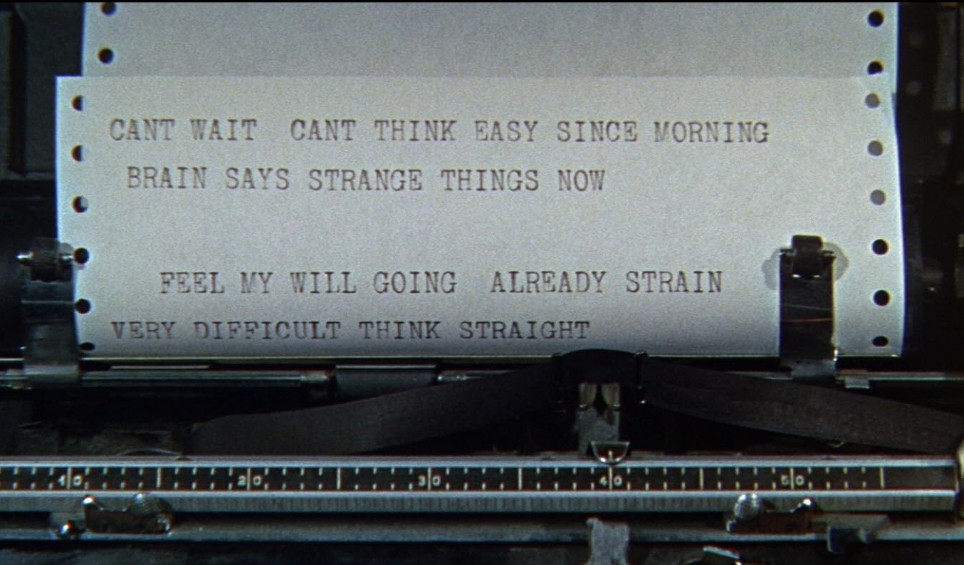

There are a couple of more back-and-forths between Helene looking for the fly and visiting Andre, until the moment that Andre informs Helene that it is too late – his mind is going, and the brain of the fly is slowly overtaking his. His left fly arm is becoming unruly and makes several passages at Helene. To Helene’s horror, Andre smashes the teleportation machine and burns all his notes, so that Helene will have no other choice but to help him destroy himself – so completely, that no-one will ever know anything about what happened to him or about his researh. The knowledge is too dangerous, and “there are some things that Man should not experinent with”.

While distraught, Helene gathers herself and calmly agrees to help Andre, and they set off to François’ factory next door, where Andre places himself under the metal press, and shows Helene how to work the machine. Then – squish. And that’s where Helene’s flashback ends, on a bloody note.

Back in real time, Charas and François deliberate whether to believe Helene or not. François is inclined to do so, while Charas sees her story as definite proof that she is indeed insane. Charas sends for nurses to come and take Helene to the insane asylum, while François takes care of Philippe. François asks Charas what might convince him to change his mind, to which Charas answers: “Find the fly”. François sighs, knowing this is an impossible task.

The final scene is one of the most iconic in horror movie history – and if indeed you have not seen it, I do not want to spoil it, even if it will make the film difficult for me to fully analyse.

Background & Analysis

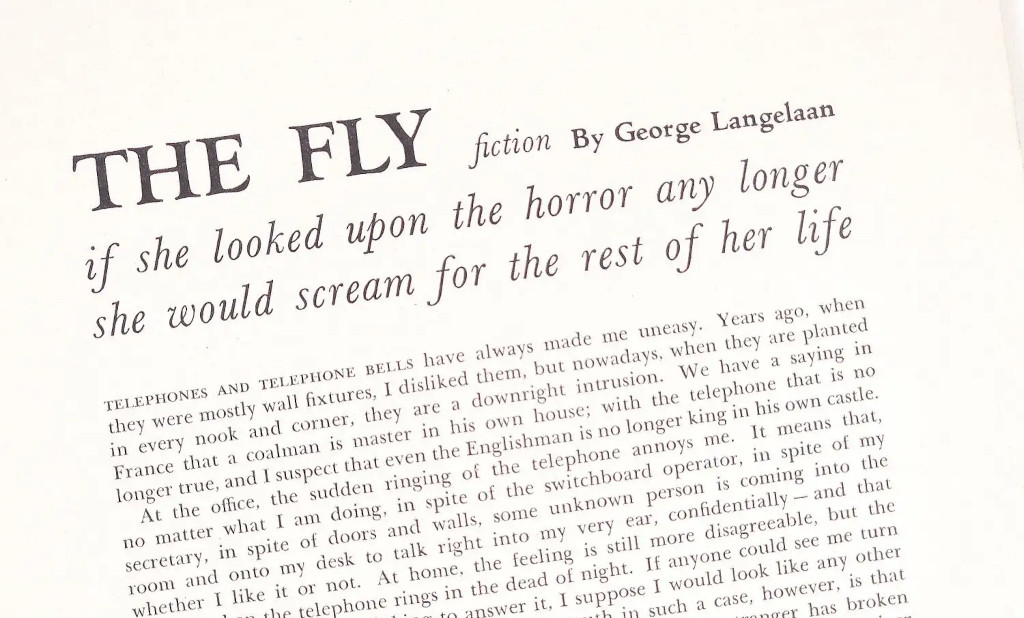

As mentioned above, The Fly was based on a short story by George Langelaan, a French-British author and journalist, who spent a large period of his author’s career in the US. This is where he got his first fictional story of note published – and it remains the one he is best remembered for, with a huge margin. That story, of course, is The Fly. It was published in 1957 in Playboy. Back in the day, Playboy was not only about pretty girls, but also featured some impressive, often cutting-edge journalism and it published a lot of short fiction that didn’t necessarily have anything to do with sex. In fact, Playboy was quite an important outlet for SF, partly owing to the fact that founder and editor Hugh Hefner was a fan of the genre. Playboy could count among its regular contributors such writers as Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson.

The Fly was immediately recognised as something new and exciting by fans and critics around the world. It was quickly released as part of an anthology of the best SF of 1957, and Playboy readers voted it as the best of the magazine’s SF stories of the year.

One of Playboy’s readers was Kurt Neumann, director of such science fiction movies as Rocketship X-M (1950, review) and Kronos (1957, review). He liked the story and thought it would make for an excellent film. At this point in time, Neumann was closely associated with Robert Lippert’s Regal Films, a subsidiary to 20th Century Fox, created to make B-movies fast and cheap – a bit like a high-profile AIP, but in the service of Fox. Lippert like the idea, and it was approved by Fox. Originally, the movie was to be made as an ordinary Regal picture, in black-and-white, and with a budget of around $100,000. But somewhere along the way, Fox developed interest in the film, and thought it could be released directly through the studio, in colour and with a substantial budget and all the bells and whistles of Fox’s publicity machinery. However, the movie was still handled by Regal, and Neumann stayed on as producer and director.

The job of adapting the screenplay went to James Clavell, an Australian-born, British-raised former professional soldier and film distributor who arrived in Hollywood in 1954, hoping to carve out a career as a screenwriter. He penned a handful of scripts, but none were produced. One, however, was bought and sold by different studios, and finally ended up at Fox. Fox didn’t produce it either, but it caught the eye of Robert Lippert, who thought Clavell was a good writer for adapting Langelaan’s story.

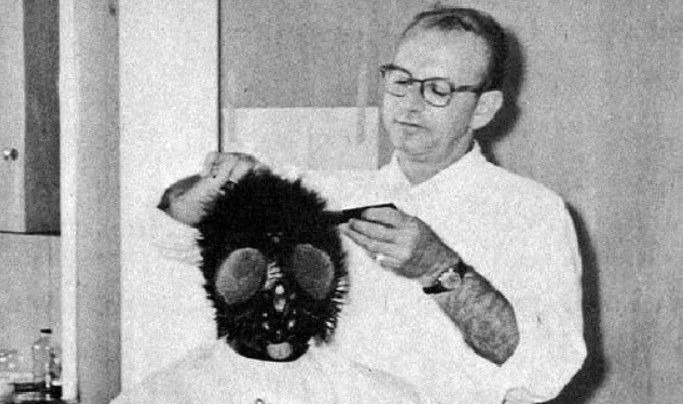

Clavell is occasionally given much credit for the screenplay – and he did do a good job adapting it – but the praise should be given straight to Langelaan. Clavell changes very little in the story, which is told in a highly filmic manner. Certain details are changed, of course: the action is moved from France to Canada, as if the keeping of the French-speaking setting was somehow important (it isn’t). The boy’s name is changed from Henri to Philippe – the studio probably thought Henri and Andre were too similar. In the story, Helene is interred in an insane asylum, while in the film she is treated at home. This may have partly been a budgetary decision, but it also makes sense to the film, as it brings the horror closer to home, juxtaposing it with the idyllic family life of the Delambres. One major change to the “monster” is that in the story, Andre takes on the characteristics of both the fly and the disintegrated cat, turning him into a fantastic human-cat-fly hybrid. This would have perhaps been a tad too gruesome for picturegoers, and it’s possible makeup artist Ben Nye might not have been able to pull off the stunt credibly. The film instead opted to go all fly – probably a wise decision. Perhaps the biggest change is the ending. The story ends on a tragic note with Helene committing suicide. The film opts for a slightly happier ending, although it is still tragic enough. But here at least, Helene and Philippe get to go on with their lives – and it is suggested, with François as a new, adopted father.

But that’s really more or less it when it comes to the changes. Clavell keeps the story intact, uses Langelaan’s chronology and dramatic arc, organises all the scenes in the same order and pretty much even keeps the dialogue intact.

At heart, the story is nothing new. It is an old-fashioned mad scientist tale warning the viewers of Man’s reach exceeding his grasp – Clavell even adds the tired cliché of “there are some things Man is not supposed to dabble in”. What makes this film different is the trimmings. This mad scientist isn’t working in some drafty old castle with a hunchback assistant, desperately trying to bring his dead wife back to life – or create an army of supermen with intents at taking over the world. No, this scientst – more driven than mad – works out of an idyllic, colourful family home. He and his wife are very much in love, they have an annoying little kid and they all seem very happy and sweet. Unlike most mad scientists, Andre doesn’t neglect his family (when he does lock himself in his lab for days on end, Helene just thinks it’s part of his charm), he is sexually interested in his wife (very rare) and he is altogether a very charming, kind, likeable guy, and, crucially, remains so until the end. Helene is also loving, smart, interested in her husband’s work, overseeing with his faults and a loving, independent, even-keeled and brave woman. We see the family and their housekeeper tinkering about in the bright kitchen, playing with the family cat and lounging in their lush, green garden. So that when tragedy strikes, and the horror seeps into the idyll, we feel the punch. We care for the characters, because not only are they likeable and sympathetic, and we have had time to invest in them – they also seem like quite normal people: a normal, happy family in a normal house in a normal city. These are people that we actually like, exceedingly rare in these kind of pictures. Kurt Neumann’s and Clavell’s genius here is to make us not only sympathise but also identify with the family before they subvert the story.

The film’s punch is dampened by anyone watching the film today, because, whether you have seen the 1986 remake or the original movie before or not, you kind of know what is going to happen. Back in 1958, nobody knew. One of the things that makes the film work so well is its structure, borrowed from Langelaan’s story. We sort of know the conclusion to the film from the very beginning: Andre Delambre dies in a metal press. But everything else is a mystery. Helene says she killed him, but offers no motive. We never see her do the deed, so as an audience, we are as much in the dark as François and Charas. We suspect that Helene is not insane, but cannot be sure. As the story progresses, and we see love and happiness permeate the Delambre family, the idea that Helene killed her husband seems ever more unlikely – but if she didn’t then who did, and why? Could it be François? Even Philippe? Did Andre manage to somehow kill himself? Was it an accident? Then why is Helene so tight-lipped? It’s an extremely well-constructed murder mystery, almost in the vein of an Agatha Christie novel. And because the main character is really the killer herself, the mystery element doesn’t seem tepid or tacked-on, as it does in many 50s science fiction films, in which the “mystery” often comes across as padding, filling out time between presentation and climax.

The script for The Fly is as good as it is because it is one of the few movie SF movie scripts that adheres closely to its literary inspiration, and the literary inspiration is a very good one. It has the courage to refuse a more traditional, linear storytelling, and doesn’t give in to the temptation to add the B-movie tropes that other producers might have instisted on. That said, the actual story is, when you get to the bottom of it, quite traditional, and fails to delve deeper into the SF themes provided – this goes for George Langelaan’s short story as well. It carries the tired old skepticism agains science and technology that addled SF and mad scientist films from the 30s onward, even tacking on that trite warning of scientists meddling in the realm of God. “The road to hell is paved with good intentions” was the moral that so many science fiction movies fed audiences for decades, and to a certain degree, still do. And while there is a debate to be had over whether a thing should be done just because it can be done, this film doesn’t lean into it. As there is no personal drama in the film – the Delambre’s are the picture-perfect Hollywood family – The Fly also provides few, if any, themes to explore on a human level. It is what it says on the label: a film about a man who becomes a giant fly.

You can poke holes in the film’s science all day. Matter transfer doesn’t work even remotely the same way as TV projection, it is physiologically impossible for a human to live with a fly’s head, and vice versa, and so on. However, the film works because it stays true to its own logic, and as film historian and critic Bill Warren points out: it works by way of analogy, not science. We know TV works by breaking down the image and reintegrating it on the screen. The analogy works for atoms as well, even if it doesn’t on a scientific level. We know that it doesn’t but the analogy is strong enough that we buy it in the context of the movie. What we don’t buy is that one silly – but creepy – scene, in which the cat seems to meow from the afterworld after Andre has disintegrated it into space. That’s because we have just been told that the cat’s atoms have been exploded and scatterered all over the room, and even within the film’s logic, atoms don’t meow.

Another very silly but utterly creepy scene is the finale, which I will not describe here. Vincent Price and Herbert Marshall thought it was so silly that director Neumann had to do 20 takes because the two actors kept bursting out in uncontrollable laughter. David Hedison, who was also part of the scene, also later stated that Neumann’s decision regarding his voice in the scene (which is what makes it so silly) was a stupid one. This is one instance where the film has – in its own way – stuck to the scientific logic of the situation, where it should perhaps have allowed itself more artistic license. Nontheless, it is a very memorable scene, and according to those who saw the film upon release, did have the intended shock effect. And it really still does, despite its silliness.

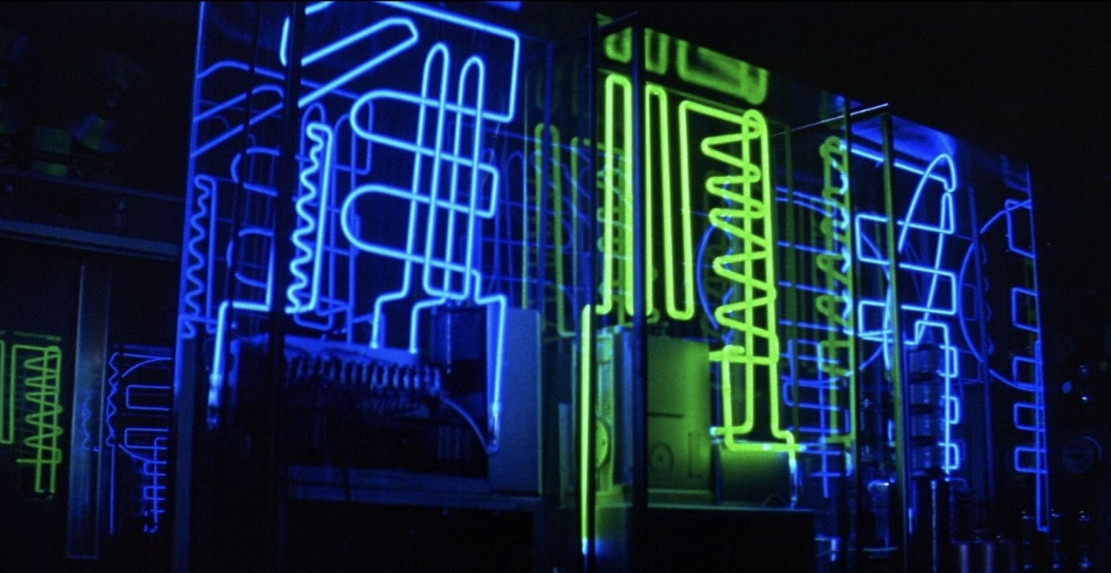

The special effects are few and far between, and seldom particularly elaborate, but they work very well. The crushed body of Andre in the beginning is surprisingly gory for the time, especially when the body momentarily sticks to the top plate of the steel press when it is raised. Part of the gore comes from the fact that the film took its cue from Hammer’s novel horror movies and depicted the blood in garish, bold red. Andre’s lab is filled with neon tubes and blinking lights. Even if it makes little scientific sense, the effect of this visual onslaught works for the movie. There almost no optical effects in the film, apart from the teleportation scenes, which are simply jump-cuts with what seems to be a combination of over-exposing the terminals and using cel animation to give them a bue glow, in order to mask the jump cut. But the bright light in combination with the loud, piercing sound effect of the teleportation, make these scenes very effective. The film’s only other optical effect is present in the final scene, and is so-so.

Bill Nye’s special makeup may seem a bit silly by today’s standards, partly because it doesn’t adhere to what we think of as a monster makeup. It’s not slimy or drooling, and has no fangs or spikes or ick. It’s a solid piece of makeup that doesn’t particularly look loke a fly’s head, but which is definitely insectoid. The “whiskers” were attached to a mouth piece which actor Hedison chomped on to make them move. Once again, the effect can be seen today as slightly comedic, but at the same time very creepy. The opaque golden eyes look a bit too much like the props they are, but otherwise the makeup is remarkably well realised and holds up quite well even to this day. To adolescent movie-goers at the time, it was reportedly very shocking. Bill Warren explains in his book Keep Watching the Skies! that, difficult that it may be to understand today, audiences at the time were not in the least prepared for Hedison to unveil a fly head. And if you watch the film carefully, there’s actually nothing in the build-up pointing to it, unless you know what is going to happen. According to Warren, audiences thought that Andre’s face would somehow be distorted, with the eyes in the wrong places or someting (as he at one point writes to Helene that he can’t see very well). On the other hand, the posters for the movie did make it quite clear that we would be dealing with a human fly. Another very effective shot is the shot of Helene, as seen through Andre’s compound eyes – a shot most likely suggested by cinematographer Karl Struss.

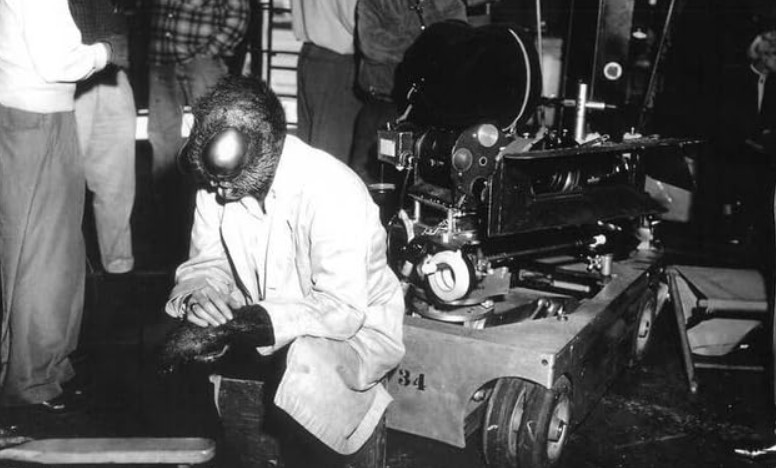

Kurt Neumann did a number of well-regarded science fiction movies in the 50s, with often decent low-budget production values and better-than-average special effects for low-budget movies. His scripts often had interesting ideas, but faltered in the narrative department. He was not an actor’s director, but his choice of good actors often weighed up this problem. The Fly is by far his best SF movie, mainly on the strength of the script, but also because he worked with a larger budget than usual. Neumann was a cabable and reliable director, but somewhat pedestrian. He knew how to present special effects and drama, but had no real visual flair. A more inventive director would have imbued The Fly with a more forebodeing atmosphere, and made more of the horror of Helene’s terror and Andre’s mutation, through the use of camera angles, framing and lighting. While the film has a few standout moments, for the most part it is shot in a rather flat and static manner.

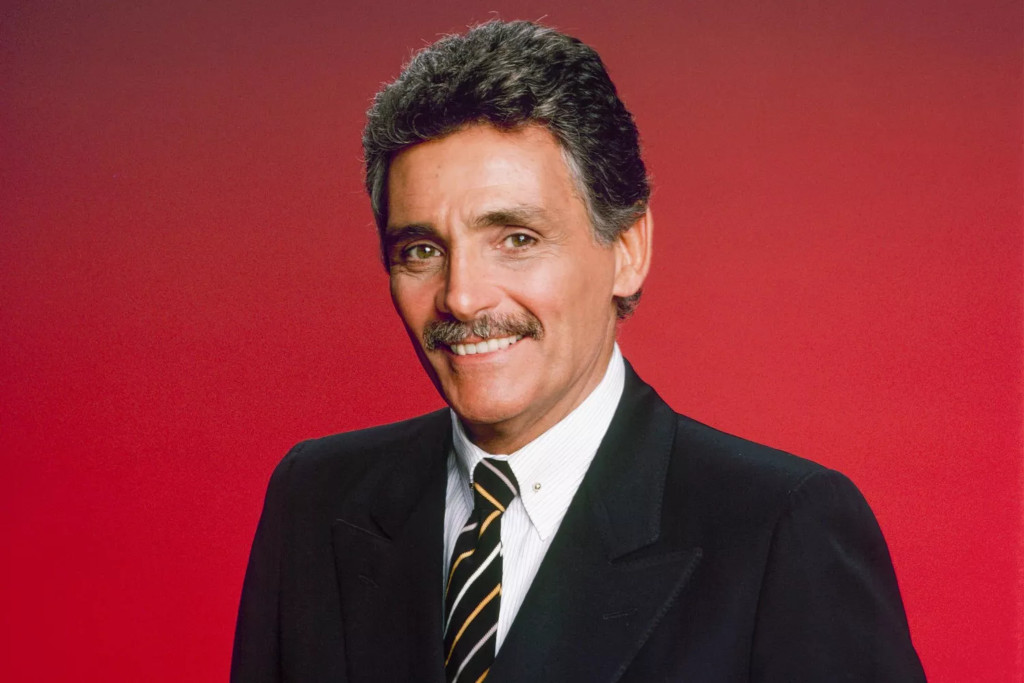

The acting in The Fly ranges from good to so-so. Today, the picture is regarded as a Vincent Price vehicle, and many who have not seen it believe that Price is the titular menace. However, Price is merely a supporting player, with the rather dull role of acting as the audience’s stand-in in the mystery plot, asking the questions we want to ask and providing us with exposition. In the original story, François was literally the narrator. It is telling that Price was third-billed in the movie – this was before he came to be regarded as a horror icon, partly on the strength of The Fly, but primarily on the strength of House on the Haunted Hill (1959), which was his real breakout role. Price was at his best in more extravagant roles, either veering towards the sinister or the comedic, sometimes both. In The Fly he gets the chance to do neither, and is therefore a bit bland as the pleasant, kindly uncle. However, Price’s charisma was always present whenever he was on screen, and The Fly is in exception.

Albert David Hedison, here billed as Al Hedison, turns in a strong performance as Andre Delambre. He is charming, likeable, funny and handsome in his early scenes, which is ultimately what sells the tragedy of his fate. His performance as the fly is an outstanding example of physical performance. The further the fly takes over his brain, he develops tics and jerky staccato movements, making him seem less and less human, and when he finally flails around the lab, battling the fly in his head, it seems real. As his mind goes, and he struggles to write LOVE YOU on the blackboard, the last words ever “spoken” by him to Helene, it is an emotional moment because we can see Andre’s desperation in Hedison’s performance.

But the real star of The Fly, and the actual protagonist, is Patricia Owens as Helene. Her job playing the Hollywood housewife is an unthankful one, but she does it with aplomb. She pulls off her scream queen moments with gusto, and registers both the terror and the sorrow in the situations with her fly husband believably. Her most challenging moments in the film is during her interrogation scenes, when she balances between the indifference she tries to show towards her interrogators, all the while remaining warm and kind, with the turmoil her character feels behind the facade, which sometimes breaks through, as in the scene where her nurse kills a fly. This really is an awesome acting challenge for any actor, and Owens attacks it admirably. However, these are the sections in which it feels as if there is something missing – an emotional depth that we’d like to see crack through the character’s performance a little bit more. When Helene plays at indifference, she seems a bit too cheerful and untroubled, considering the ordeal she has just gone through – too genuinely unworried about her situation and her actions, which strangely enough actually makes her seem like a psychopath. Which, obviously, isn’t the aim of the performance. This said, many B-movie leading ladies would have balked at this challenge, and Owens comes through with one of the best performances of a leading actress in a 1950s science fiction movie. This is not necessarily a putdpown of her peers, but mostly a praise of the unusually well-written part.

Herbert Marshall, playing the inspector, was a star name of yesteryear and apparently didn’t think too highly about appearing in a science fiction B-movie. Marshall is able to muster very little enthusiasm for his role, and mumbles his way through the part, making it sometimes very different to hear what he is saying. In his defence, his part is, like Price’s, quite flat to begin with. The movie also features Charles Herbert, he of the furrowed eyebrows, a popular child actor in the late 50s, often playing inquisitive and/or mischieavous kids. Herbert acts in that over-emphasised style, shouting all his lines from the bottom of his lungs, that was so popular in the 50s, and which haunts child performances even to this day. The movie also features the fantastic Kathleen Freeman in the role of maid Emma, blunt as ever, and with impeccable comic timing. Freeman adds some much needed levity to the otherwise heavy proceedings of the second half of the film.

The Fly is a very good horror movie. As science fiction, it brings little new to the table – it is mainly an update on the old mad-scientist-turns-into-a-monster trope. It doesn’t deal with any particularly interesting philosophical, psychological, social or political themes. The “boundaries of science” theme that is present is treated as little more than a trope and largely feels tacked on. It is, however, an extremely entertaining mystery/horror film, largely on the strength of its well-crafted dramatic arc and screenplay. The story structure is not new as such, but feels fresh and unusual – and most importantly: it serves the story. We get unusually fleshed-out characters that we genuinely like and care for, making The Fly’s impact an emotional one, which is quite rare in late 50s horror/SF outings. It would probably have worked just as well in black-and-white, but the colour photography makes it feel classier than it actually is. Kurt Neumann’s direction is competent if pedestrian, the special effects, art direction and production values are all solid, and the acting likewise on a better than usual level for these kind of films. It’s not a masterpiece by a long shot, but an entertaining, gripping and startling horror film that holds up remarkably well today.

Reception & Legacy

The Fly was released with a big ballyhoo in July 1958 – including one of the best trailers in history – and premiered simultaneously in over 100 theatres in New York alone. It was something as unusual as a science fiction blockbuster, and made between $3 and $4 millions, according to various sources, making it one of 20th Century Fox’s biggest movies of the summer.

Reviews were generally very positive. Howard Thompson at The New York Times noted that the film contains “two of the most sickening sights one casual swatter-wielder has ever beheld on screen”, but that, otherwise, The Fly was “one of the better, more restrained, entries in the ‘shock’ school”. Jack Moffitt in the Hollywood Reporter noted the makers’ “dramatic skill”, and called the movie “as fine an A picture as the best”. Jean Yothers at The Orlando Sentinel said that the movie “will send cold chills down the spines of the most hardened horror addict”.

The Film Bulletin chose The Fly as one of its picks for the summer’s best movies, calling it “an exceptionally cleverly devised ‘gimmick’ film with bone-chilling horror overtones”. Harrison’s Reports, although often averse to gore, was also highly positive, calling The Fly “a first-rate science fiction-horror melodrama” that “grips one’s attention from the opening to the closing scenes, and is filled with spine-chilling, suspenseful situations that will keep movie-goers on the edge of their seat”. Powe in Variety called it a “high-budget, beautifully and expensively mounted exploitation picture”. The critic noted its “unusual believability” and opined that its structure as a mystery story gave it an interest beyond the macabre effects. Powe also praised the photography, the art design and the special effects. Photoplay gave it 4/4 stars, writing: “Not since The Thing has a film combined science fiction and horror so skilfully, with steadily mounting tension”. High praise indeed.

The Fly is one of a small handful of films we have reviewed so far on Scifist that has been chosen as relevant enough to get a mention on review aggregate Metacritic, where it gets a “generally favorable” 62/100 rating. Rotten Tomatoes has a 7.0/10 critic consensus. As of writing, the movie has a 7.1/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on over 26,000 votes, and 3.5/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on 25,000 votes, making this by far the most widely watched movie we have reviewed in a long time.

Later reviews have, however, been somewhat mixed. In a write-up for the New Yorker, Pauline Kael called The Fly “a tacky low-budget picture” with “draggy direction […] by Kurt Neumann“. Dave Kehr at the Chicago Reader said: “Slightly above average 50s science fiction, enlivened by a nearly literate script by James Clavell“. BBC gave it 3/5 stars, calling it “a sad story of considerable pathos despite the ridiculous plot”. Entertainment Weekly gave it a B- rating, calling it “talky, stilted, and often just plain silly”, noting that ” time hasn’t been kind to it”. On the other hand, TV Guide labels The Fly as ” both fun and frightening” and says that “[it] can [..] be viewed as a commercialized techno-version of Franz Kafka’s allegory Metamorphosis“. And Brandon Ciampaglia at IGN gushes almost poetically in an 8/10 review at IGN, saying the movie is “one of the most influential and thrilling science fiction films of all-time”.

The Fly’s enormous success promtped Fox and Robert Lippert to produce two sequels, Return of the Fly (1959) and Curse of the Fly (1965). Ignoring the fact that only a year had passed since the original film, Return of the Fly followed a grown-up Philippe trying to recreate his father’s experiments, but running into complications with an industrial spy. The movie was shot in black-and-white, with Vincent Price the only returning actor – and is generally considered much inferior to the original. The second sequel was produced as part of a number of films Lippert made in England. The Curse of the Fly clearly aimed at setting up a Frankenstein clan worthy of the old Universal films, as this movie follows Andre’s other son (who apparently exists) and his grandsons, again walking in the footsteps of the old teleportation tinkerer.

Fox dusted off the old swatter in 1986, and enlisted the master of body horror, David Cronenberg, as director, and attached Jeff Goldblum and Geena Davis as stars of the picture. The remake is generally seen as even better than the original, and was the film that turned Cronenberg into a household name. Cronenberg ditched the family angle, and instead turns the protagonist, now named Seth Brundle, into an obsessed loner, and the personal drama into a love triangle. The movie’s gruesome special and makeup effects earned it an Oscar. A sequel, The Fly II (1989), was directed by said Oscar-winning makeup artist Chris Walas, and follows Martin, the offspring of Davis and the the Brundlefly, exploring his origins. The movie got a lukewarm reception upon releaese, and is more or less forgotten today.

A third remake has been rumoured to be in the works for nearly ten years, and as late as 2023, “trusted sources” revelaed that the project was in the planning stage under Fox, with J.D. Dillard attached as director and Marvel star Zendaya as the lead. However, no new information on the project has surfaced lately.

In 1959, the original The Fly was nominated for the Hugo Award for best SF or fantasy movie – however, voters selected not to award a winner in the category that year (oddly, as it featured such landmark movies as Hammer’s Dracula, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and The Fly).

Cast & Crew

Director Kurt Neumann was born in Germany in 1908. He worked briefly in the German film industry in the late 20s, and had only directed one short movie before he was brought to Hollywood to direct German-language versions of Hollywood movies. This was during the short-lived era at the beginning of sound films that studios would make the same movie in different languages, often with different actors and directors. However, Neumann quickly mastered English and established himself as a director in his own right, and made a couple of well-regarded films for Universal in the early 30’s. These included The Big Cage (1932), a circus movie which included several scenes with lions and tigers being handled by lion tamer Clyde Beatty, that were famously re-used in the SF/horror film Captive Wild Woman (1943, review). He freelanced for almost all major studios, before being picked up by RKO to direct a string of Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films in the early 30’s. Neumann worked primarily on B-movies for major studios, but also freelanced for smaller outfits like Monogram and Allied Artists.

In 1950 crafty freelance producer Robert Lippert took advantage of the media hubbub around George Pal’s upcoming Destination Moon (1950, review), and hurried out the low-budget movie Rocketship X-M (review) a few weeks prior to Pal’s humdrum moon adventure. As director, he hired Neumann, and as cinematographer Karl Struss, and the duo was able to make a surprisingly competent space movie on a short schedule and little money. Neumann has since been labelled as a “science fiction specialist”, but in truth he didn’t make that many SF movies. Along with Struss as his cameraman, he directed Kronos (1957), She Devil (1957) and perhaps most famously, The Fly (1959, review). By modern critics, Neumann is generally regarded as a competent but pedestrian director, who was neither very good with actor nor provided much visual interest in his movies – although several of his SF movies are aided by Struss’ photography and often above-average low-budget special effects.

Karl Struss was one of many once highly lauded veteran cinematographers who found themselves sidelined after WWII – Roger Corman’s ace photographer Floyd Crosby was another – and relegated to B-movies. Struss was a favourite of Neumann’s and they worked together on many films in the 40s and 50s. But in his earlier career, the New Yorker was one of the hottest cinematographers in Hollywood, with credits for F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review), Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940). He also shot one of the best sci-fi films of the 30s, Island of Lost Souls (1932, review). He also, bizarrely, filmed the turkey Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review) and The Alligator People (1959).

Much can be written about the long and checkered career of Robert L. Lippert, the executive producer of The Fly. In short, Lippert (b. 1909) worked his way up from menial jobs at a movie theatre to becoming the theatre manager during the Great Depression, often luring customers with different gimmicks. His successful tactics saw him quickly expanding his chain of theatres, until in 1948, he owned over 70 cinemas (a number that would later expand to 139). In 1945 Lippert became, in his own words, fed up with the “exorbitant” rental fees charged by the major studios, and thought it would be cheaper to produce films himself. He founded the production company Screen Guild Productions, which eventually became Lippert Pictures in 1948.

Lippert mainly focused on simple entertainment; westerns, musicals, detective stories, comedies, etc, mostly through independent producers. But he also made a number of fantasy and science fictions films – most importantly, perhaps, Rocketship X-M (1950, review), the first American film about a manned mission to Mars, rushed into production in order to capitalise on all the hubbub around George Pal’s announced big-budget production Destination Moon (1950, review). Although filmed on a much smaller budget and with impoverished production values, Rocketship X-M proved to be a much sprightlier picture than the wooden – if visually impressing – Destination Moon.

Lippert was a sly businessman and marketer. He placed his company squarely between the low-budget studios and major studios, providing low-budget entertainment with a touch of class. When major studios let go of many of their stock actors and quit producing B-movies, many actors with name recognition found a temporary home with Lippert when they went freelance. He would also shoot many films in colour, or partly tinted, like Rocketship X-M, to give them a sense of luster. In 1951 he entered a deal with Hammer Films, importing the British studio’s production to the US, and vice versa. He was also one of the first major Hollywood producers to try to sell his movies to TV, which led to a highly publicized dispute with the Screen Actors Guild. This was a time when the movie business still refused to have anything to do with television.

Another chapter in Lippert’s story came in 1956, when he struck a deal with 20th Century Fox. Fox director Darryl F. Zanuck approached him with an offer to let him produce a string of B+ movies using the new CinemaScope format that Fox had just released. This was partly as a way to appease theatre owners, who had to convert their theatres for the new format – and were still upset about having recently had to upgrade their theatres for 3D movies, a fad which disappeared as quickly as it started in the early 50s. Zanuck assured theatre owners they would have a steady stream of CinemaScope movies coming their way, not just A films from Fox, but also B movies from Lippert’s new company, named Regal Films. Through Regal, Lippert signed a contract for 20 movies a year over a period of seven years. They were all to be shot on a budget of $100,000 in seven days. However, due to Lippert’s dispute with SAG, Fox didn’t want his name on the product, so another person was officially named head of Regal Films, and Lippert’s name never appeared in the movie credits, although held all de facto power.

Lippert’s involvment with Fox lasted until 1962, at which time he claimed to have produced “300 films in the last five years”, including 100 for Fox. The company was renamed to Associated Producers Incorporated (API) in 1959. After his contract with Fox ended, Lippert started producing films in the UK, claiming Hollywood had made it impossible to produce cheap B-movies with rising costs. Between 1963 and 1965 he produced half a dozen films in the UK, including the SF’s The Last Man on Earth (1964), Curse of the Fly (1965) and The Earth Dies Screaming (1965). And despite ending their contract with Regal, Fox still distributed his films in both the UK and the US. Lippert returned to the US in 1966 and produced a few movies for Fox before retiring from production in 1967. He then focused on his theatre chains, which he managed until his death in 1976. All in all, Lippert produced around 250 films for Fox, and probbaly more than 150 for other companies.

Exactly how many science fiction movies Lippert had his hands in is impossible to tell without going through all the productions of his different companies, which I am not prepared to do right now. However, they amount to at least 20. Apart from the afore-mentioned, one can highlight the hollow Earth movie Unknown World (1951, review), Hammer’s Spaceways (1953, review) and The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review), Bert I. Gordon’s King Dinosaur (1955, review), Roger Corman’s Monster from the Ocean Floor, (1954, review), Regal’s Kronos (1957, review), Space Master X-7 (1958, review), The Fly (1958), Return of the Fly (1959) and The Alligator People (1959).

British-Australian screenwriter James Clavell later became famous as an author. Clavell served with the Royal Navy in WWII, and was captured by the Japanese. Spending time at a prison camp, he was released with the ending of the war, but continued in the navy, from which he was discharged in 1948 after a motorcycle accident. His marriage to a British actress made him interested in the movie business, and he tried to get into both producing and screenwriting in Britain with little success. In 1954 he moved via New York to Los Angeles, and wrote a couple of scripts that got picked up by studios but never produced. One such was a movie about pilots called Far Alert. The script was traded between several studios, without ever being produced. Clavell didn’t complain: “In 18 months it brought in $87,000. We kept getting paid for writing it and rewriting it as it went from one studio to another. It was wonderful.” It was this script that finally landed with Fox, where Robert Lippert saw it, and on the strength of it commissioned Clavell to adapt George Langelaan’s short story for The Fly (1958), which became Clavell’s first produced movie script. It was on the strength of this script that he got his first directorial assignment in 1959. Over the years he directed 10 movies, and also started producing. He had a hit in 1967 with the Sidney Poitier vehicle To Sir, With Love, but his succequent movies flopped, and he turned from this path.

He continued, however, to write screenplays, for such films as The Great Escape (1963) and The Satan Bug (1965). His greatest success came as a novelist. In 1960 he published King Rat, based on his experiences as a POW. It was a great commercial success, and Clavell consequently found fame writing books set in Asia, predominantly Japan, such as Tai-Pan (1966) and Noble House (1981), all bestsellers. His best known novel is the 1975 epic Shogun – which serves as the basis for the current smash hit streaming series Shogun (2024), which recently cleared the table at the Emmys.

Albert David Hedison, Jr., billed in his early career as Al Hedison, and from 1959 onward, reluctantly, as David Hedison, was a good-looking, charming and talented actor who was most at home in somewhat “sophisticated” roles, as authority figures and patriarchs, which served him well in everything from science fiction and fantasy to James Bond movies and soap opera. His true home was the stage, on which he got started in the early 50s, before getting signed to 20th Century Fox in 1957. The role of Andre Delambre in The Fly (1957), as the sympathetic scientist who accidentally turns himself into a human fly, was his breakout role. Two years later, he played a co-lead in Irwin Allen’s adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1960). The next year he was offered another lead in Allen’s movie Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961) as Captain Crane, but turned it down. However, when Allen offered him the same role in the TV series with the same name in 1964, he accepted, playing it with great success for the next four years.

All the while, Hedison continued to appear on stage and in smaller films and doing guest spots on TV, including a stint in the British hit show The Saint in 1964, which led to a life-long friendship with Roger Moore. He left for London in the late 60s, according to his own words because he wanted to live there for a while. He later stated that he enjoyed his two years in the UK, but had a hard time getting cast when he returned to the US. However, his old friend Moore came through in 1973 and got him cast as CIA agent Felix Leiter in the 007 movie Live and Let Die. He reprised the role opposite Timothy Dalton in Licence to Kill (1989), making him the only actor to play Leiter twice. His appearance in a Bond movie strenghened his stock on the market, and for the rest of his career he was steadily employed as a TV guest star. Between 1991 and 1995 he had a recurring role in 72 episodes of the NBC soap opera Another World and in 2004 appeared in 50 episodes of another soap opera, The Young and the Restless. In the 2000s, Hedison appeared in a handful of low-budget movies, like Fred Olen Ray’s Mach 2 (2000) and Eric Stoltz‘s Confessions of a Teenage Jesus Jerk (2017), which was to be his last role. David Hedison’s science fiction movies are The Fly, The Lost World, Brian Trenchard-Smith’s Megiddon: The Omega Code 2, starring Michael Biehn, and Spectres (2005), featuring an all-star cast of SF notables, like Marina Sirtis and Linda Park of Star Trek fame, Dean Haglund of The X-Files and Tucker Smallwood.

Canadian Patricia Owens moved to London in 1933, when she was eight, and here she took to the stage at an early age, and made her motion picture debut in 1943. She worked steadily in the theatre and was offered small or supporting parts in film, until a talent scout for 20th Century Fox in 1957, who offered her a contract with the Hollywood Studio. However, much of her work during her first year in California was on loan to other studios, most importantly Warner, for whom she memorably played Marlon Brando’s scorned girlfriend in Sayonara (1957). Her big break came as Helene Delambre in Fox’s own The Fly in 1958, but despite good notices, her career didn’t take off, and it remains her best remembered role. She continued appearing in B-movies and in guest spots on TV shows for another ten years, but then decided to call it quits. She also appeared in the 1968 spy-fi thriller The Destructors.

Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing and Vincent Price. I dare anyone to contest that these are the five giants of horror acting history. From haunted houses and wax museums to Alice Cooper and Michael Jackson, from Edgar Allan Poe to the Muppets to Scooby-Doo, Vincent Price is the voice of horror. And while many consider The Fly (1957) a Vincent Price vehicle, the fact is that in 1957 Price was neither particularly famous nor connected to the horror genre.

Born into a wealthy industrialist family in St. Louis in 1911, Price was set at a career in the arts, having studied in Yale and London, when he was bitten by the acting bug while in Britain, and started working professionally as an actor on the London stage, eventually relocating to New York. He made his film debut in 1938, and his refinement, eloquence and theatrical flair made him a natural for costume dramas. But Price early on also showed a mischievous and playful streak in his acting, which combined with his distinct voice, a unique blend of velvety baritone and an ominous creak, made him well cut for sinister, even unhinged roles. One of his earliest showcases was the lead in Universal’s The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review), where he fills in the shoes of Claude Rains, another actor with a truly memorable vocal performance. But despite the occasional venture into horror, like House of Wax (1953), he was more likely to be seen in roles such as Richelieu in The Three Musketeers (1948), or as sinister characters in film noirs.

The Fly actually marked an unusually bland and sympathetic character for Price, to the point that he is not particularly memorable in the movie. But his association with the film, as well as three horror movies released in 1959; The Tingler, The Bat, and, most notably, House on the Haunted Hill, cemented his reputation as a horror actor. That same year he also appeared in Fox’s sequel, Return of the Fly. In 1960, Roger Corman called upon Price to star in The Fall of the House of Usher. Price and Corman bonded over their love for Edgar Allan Poe and a mutual pencheant for mixing the macabre with tongue-in-cheek humour, and during the course of four years, they made half a dozen Poe adaptations, which have remained Price’s most lasting legacy. There are several other memorable horror roles worthy of mention, but since we do not specialize in horror here on the Scifist, we’ll just direct you the eminent Robin Bailes’ video on Price’s top 10 horror roles, and his video on Corman’s Poe cycle. All in all, Price appeared in over 110 movies and almost as many TV shows in a film career that spanned seven decades.

Price also appeared in a dozen science fiction movies, starting with The Invisible Man Returns (1940) and continuing with The Fly (1958) and Return of the Fly (1959). He starred as Robur the Conqueror in AIP’s adaptation of Master of the World (1961), brought to life some of the creepy characters by Nathaniel Hawthorne in the anthology film Twice-Told Tales (1963) and became a vampire/zombie hunter in the post-apocalyptic The Last Man on Earth (1964), one of his most well-remembered roles, but according to some, Price was also miscast as the everyman character in the center of the film. He played a mad scientist in the SF comedy Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1965) and reprised the role in the Italian sequel Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs (1966). In 1965 he played another Vernean character in War Gods of the Deep, and in Scream and Scream Again (1970), he teamed up with Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, playing a campy version of a modern-day Dr. Frankenstein. In 1988 he had a supporting role in the SF action comedy Dead Heat. And while it isn’t generally considered science fiction, one must also mention Price’s brief but touching performance as the creator of Johnny Depp’s artificial boy in Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands (1992), which was to become his penultimate screen appearance.

Price continued appearing on stage throughout his career, and is particularly well-known for his one-man show as Oscar Wilde, with which he toured the world in the 70s and 80s. He also, unsurprisingly, had a thriving career in radio and as a voice artist, notably providing spooky narration to well-known songs by Alice Cooper and Michael Jackson. Price was also a noted art collector, expert and preserver, and was involved in political activism against racism and intolerance, and was also involved in projects aimed at preserving and encouraging Native American art. He and his wife donated a large part of their collection to museums and colleges, and championed public access to fine art. In addition, he was a gourmet chef and published several best-selling cook books. He literally smoked himself to death and died of lung emphysema in 1993, albeit at the respectable age of 82.

While Herbert Marshall and Kathleen Freeman deserve their own biographies, we’ll have to leave them for another time, as this cast & crew section is lengthy enough as it is. For more on the tragic story of Charles Herbert, see my upcoming review of The Colossus of New York (1958, review).

Janne Wass

The Fly. 1958, USA. Directed by Kurt Neumann. Written by James Clavell. Based on the short story The Fly by George Langelaan. Starring: David Hedison, Patricia Owens, Vincent Price, Herbert Marshall, Charles Herbert, Kathleen Freeman, Betty Lou Gerson. Music: Paul Sawtell. Cinematography: Karl Struss. Editing: Merrill White. Art direction: Theobal Holsopple, Lyle Wheeler. Costume design: Adele Balkan. Makeup: Ben Nye. Special effects: James Gordon. Produced by Kurt Neumann for Regal Films & 20th Century Fox.

Leave a comment