Four astronauts crash land on the female-only planet of Venus and join Zsa Zsa Gabor in her revolt against the evil queen. Allied Artists’ 1958 colour Z-movie is an attempt at a spoof, but it is impossible to distinguish from the films it tries to make fun of. 2/10

Queen of Outer Space. 1958, USA. Directed by Edward Bernds. Written by Charles Beaumont & Ben Hecht. Starring: Zsa Zsa Gabor, Eric Fleming, Paul Birch, Laurie Mitchell. Dave Willock, Patrick Waltz, Lisa Davis, Barbara Darrow, Marilyn Buferd. Produced by Ben Schwalb. IMDb: 4.6/10. Letterboxd: 2.5/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 4.2/10. Metacritic: N/A.

In the futuristic year of 1985, a trio of astronauts take off in a rocket for a routine job of taxying renowned scientist Professor Konrad (Paul Birch) to the international space station orbiting the Earth. En route, mysterious disintegrator beams blow up the station, and some force drags the rocket to an alien planet.

So begins Allied Artists’ 1958 cult camp classic Queen of Outer Space, a low-budget space spoof shot in colour and CinemaScope, and best known for starring the Kim Kardashian of the 50s, Zsa Zsa Gabor.

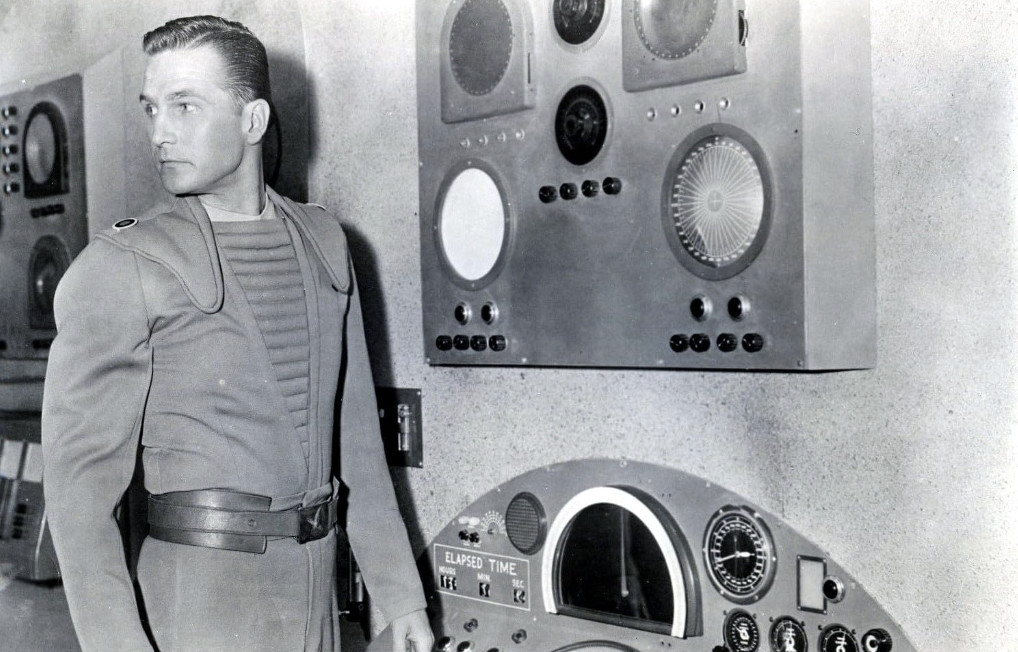

Well down on the planet, let’s meet our team. There’s Capt. Patterson (Eric Fleming), the team leader and our straight man hero. Then we have Lt. Turner (Patrick Waltz), the team’s lover boy and comic relief number 1. Lt. Cruze (Dave Willock) is comic relief number two and also the bumbling astronaut. Finally, Prof. Konrad is the brains of the mission, and the elderly bearer of wisdom.

The team calculate that the atmosphere on the strange planet must be breathable, as the planet’s gravitation is almost the same as Earth’s. After strolling around a forest for a while, Konrad is convinced that the planet is Venus, although it doesn’t conform to any scientific fact we know about Venus. That’s as good an argument as any for it being Venus, one supposes. After grinding the plot down to a halt for Turner’s long-winded jokes about little green men with eyes on sticks, our heroes finally fatigue out and fall asleep. The next morning they are captured by a group of leggy supermodels patrolling the forest in high heels, miniskirts, perfectly cioffed hair and awkward ray guns.

They are taken to a Venusian city ruled by the masked queen Yllana (Laurie Mitchell) and her ruling council. Yllana explains (in English, as they have monitored our radio waves) that the Venusians have a hatred for wars and men, especially quarrelsome Earth men. The Venusians blew up the space station, as they beleived it was the base for a planned war against Venus. The men are now demanded to reveal the secret war plans of be killed.

Of course, there are no secret war plans, which is guessed by one of Yllana’s handmaidens, the beautiful Tallea (Zsa Zsa Gabor), the leader of a resistance movement planning to overthrow the evil queen. Talleah visits the men in their (rather lavish) prison cell, where she, in another talky scene, explains the history of the planet. In short: men’s wars prompted the women of Venus to revolt and take power 10 years ago. The men were killed off, except a few scientists who were imprisoned one of the planet’s moons to do science stuff, because women are too dumb to do science stuff. They built a disintegrator machine capable of blowing up Earth. But many of the women long for the old days when men ruled Venus, and are fed up with their evil queen. Now that they have some men again, they can enact their revolt.

But before Talleah can spring them from their cell, Capt. Patterson is called to the queen. Prof. Konrad noted that the queen had eyes for only Patterson when they were first interrogated, and suggests that Patterson use his sex appeal to bend the queen to his will. And well he tries, and it sort of works, until he removes the queen’s mask, and reveals a horribly disfigured face, scarred by radiation burns from the men’s wars. Yllana, who has in reality seen through Patterson’s attempts at seducing her, taunts him by asking if he still wants to kiss her. Patterson turns away in disgust and is sent back to his cell.

However, Talleah and a group of rebels (one for each of the soldiers) spring the prisoners, and lead them through corridors and tunnels to the same place in the forest where the men fell asleep (because the film had no more sets) and they all hide behind a bush, where the soldiers and women have their own meet-cutes. They spend the night in a cave and have a terrible time necking each other. The next morning they are captured, having accomplished nothing, and taken back to prison, where they are now about to witness the destruction of Earth. However, Talleah tricks the queen and they manage to tie her and hide her behind a dresser screen (apparently the palace has no closets). Talleah takes the queen’s mask and plans to impersonate the ruler, ordering the attack on Earth to be canceled, seemingly not worried that the citizens might question why their queen suddenly has a thick Hungarian accent. But as the guards arrive, Yllana kicks the dresser screen, revealing her whereabouts, and the gang are once again arrested. Now all are brought to the great disintegrator machine to watch the destruction of Earth. However, it turns out that Talleah’s minions have sabotahed the machine, which blows up with evil Queen Yllana inside. Talleah is named new queen, and she orders the Venusian men to be released from their captivity, and thanks the Earth men for saving their planet (despite the fact that the Earth men have done absolutely nothing). On viewscreen from Earth, the Earth commander says that he regrets that the team will have to wait for a year for a rescue mission to arrive, so they will be stuck with entertaining the sex-hungry supermodels of Venus for the tike being.

Background & Analysis

In the film’s defense, it was reportedly made as a spoof. According to research done by Tom Weaver and Bill Warren, it all started in 1951 when Walter Wanger, a big-time producer for the big studios, announced that he was planning a movie called “Queen of the Universe”. According to Wanger, it was supposed to be a satire on a planet ruled by women. And then, in December the same year, he took a gun and shot his wife, actor Joan Bennett’s, agent in the crotch because he thought they had an affair. He was sentenced to four months in prison, and after his release, the major studios cut all ties with him. However, minor studio Allied Artists, formerly Poverty Row studio Monogram, offered him a lifeline, and he was able to produce smaller films for them during the rest of the 50s.

He brought with him to the studio his old idea of a satire on a matriarchal society on Venus. According to statements, Wanger presented his idea, along with, allegedly, a ten-page story treatment written by Oscar-winning big time screenwriter Ben Hecht, the writer of Gone With the Wind (1940), Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1947). However, for reasons unknown, Wanger didn’t end up producing the film. That job instead went to Ben Schwalb, a producer with a significantly lower profile. The job of adapting Hecht’s outline into a script went to Charles Beaumont, a young screenwriter who would go on to write a number of fairly accomplished horror, mystery and science fiction films and teleplays. Reportedly, Beaumont wasn’t particularly fond of Hecht’s outline, but decided it might work if it was made into a spoof. There’s conflicting reports as to whether Beaumont wrote a straight script which director Edward Bernds then decided to spoof up, or whether a spoof was Beaumont’s intention all along. Bill Warren leans towards the latter. In the process, the title was also changed to Queen of Outer Space, as the studio thought “Queen of the Universe” sounded too much like a beauty pageant.

As stated, Edward Bernds was signed on as director, probably on the strength of his previous science fiction films, World Without End (1956, review) and Space Master X-7 (review). But Bernds was really a comedy specialist, having worked with several Bowery Boys films and The Three Stooges.

I have found no information on the budget of Queen of Outer Space, but it was most certainly lower than Allied Artists’ previous science fiction film in colour and CinemaScope, World Without End, which cost $400,000. This is partly evidenced by the re-use of sets, props, special effects and costumes from a number of other movies. The uniforms worn by the space crew were hand-me-downs from Forbidden Planet (1956, review), as were several of the dresses worn in the movie. The rocket launch is stock footage from a real rocket launch, and as soon as we get to space, the miniature rocket footage is lifted from Flight to Mars (1951, review), and had already been reused in World Without End. The spaceship interior was also a hand-me-down from Bernds’ own World Without End. All in all, I would suspect that Queen of Outer Space had a budget of around $200,000. The CinemaScope process added little to the cost, as it really only required a special lens, which could be mounted on a normal camera.

The thing that often made CinemaScope films more expensive was that there was more screen to fill, which pushed up production costs. Not so much in Queen of Outer Space. The movie is filmed almost entirely on set, including all the outdoor scenes on Venus. The sets are all sparse and one-dimensional, more often than not shot entirely from a single angle, revealing the movie’s low budget. All scenes shot in the forest of Venus are shot on the same outdoor set, from the same angle, barring a couple of cutaways. Most hilarious is when all the crewmen and their female rescuers hide from the evil queen’s forces’ bombardments behind a couple of flimsy bushes. While the indoor sets of the Venusian city are often wide, they are also bare – mostly consisting of undecorated halls painted in some garish colour or the other. These may well have been hand-me-down sets from some other movie, simply painted over. Several shots use the same trick that Roger Corman used in War of the Satellites (1958, review), and director Edward Bernds in his own World Without End: using a number of arches stacked in front of each other so they form a corridor. We never really see anything of the Venusian society: the Venusians seem to little else than gather in their great hall, patrol the corridors with ray guns, and work in their tiny little biology lab. The only actual living quarters we see is that of the queen, which doesn’t look any more regal than my bedroom, with furniture that seems to have been bought at the nearest low-budget interior design shop. The disintegrator machine is a laughable piece of plywood set design – Bernds has later claimed that this was intentional, but I have my doubts. As stated above, the spaceship interior was reused from World Without End, however, the rather neat control panels and reclining seats have been removed and replaced with bunk beds. There are not really any visual effects that are not lifted from other movies, and the special effects are mostly confined to smoke bombs and sparks.

The design of the sets and the Venusian ladies’ dresses are taken straight from the world of pulp magazines and comic books. The ladies parade around both city and forest in colour-coded mini skirts and plastic high-heeled shoes, very reminiscent of the dresscode of Flight to Mars. Whether intentional or not, it is hard not to smile at the armed guards awkwardly stumbling around the forest set in their impossible footwear. The evil queen’s disfigurement makeup is quite effective, but not of particularly high quality.

Queen of Outer Space is surprisingly difficult to review because it’s unclear if one should take it as a satire, a spoof or a seriously intended film. It seems clear that Walter Wanger’s initial intent was to make a spoof of the feminist undercurrents in US society in the early 50s. This was a popular trope in early 50s SF – a part of the backlash against the growing influx of women on the labour market, in universities, politics and in leading positions in society, which itself was enouraged during WWII, as a lot of the men were off fighting in the war. When the war was over, there were forces in society that wanted to “bring back normalcy” to society, and this was one of the driving forces behind the push for so-called “traditional family values” and the de-feminization of the public discourse that was pushed by Hollywood.

Several films were made in the 50s satirizing the idea of a matriarchal society, including Untamed Women (1952, review), Cat-Women of the Moon (1953) and Fire Maidens from Outer Space (1956, review). Bernds also brought his own variation on the topic in 1956 with World Without End, depicting a society in which all males have become “effeminate”. Another insidious trope along the same theme was that of the “female scientist”, pushing the idea that a woman could not be a “scientist” and a “woman” at the same time, perhaps most vitriolically expressed in films like Rocketship X-M (1950, review) and Project Moonbase (1953, review) – granted, Colonel Briteis in Project Moonbase was not a scientist, but a military officer, but the idea is the same. The trope of the matriarchal society had fallen somewhat by the wayside by the late 50s in the movies, but was still heavily featured in science fiction and adventure TV shows.

Perhaps feeling that Wanger’s satire on women in power was becoming a bit stuffy even in 1958, either screenwriter Charles Beaumont or director Edward Bernds seems to have decided to spoof the subgenre lightly instead of making a “straight” satire. However, how much spoofing was actually intended is a matter of debate, as the two can’t seem to agree on whose idea it was. Beaumont has claimed that he wrote his script as a spoof, whereas Bernds claims that the script was written straight, and that it was Bernds that added the spoofing.

The problem with spoofing films like Cat-Women of the Moon and Fire Maidens from Outer Space is that these films are so terrible that they do an excellent job of spoofing themselves. The only way to spoof dumb films is to make the spoof so much more intelligent. Queen of Outer Space fails miserably in this, instead attempting to out-dumb these already dumb pictures. Because the source material is already so bad, it is difficult to discern if Queen of Outer Space is actually a spoof or just another one in the line of risible, misogynistic science fiction movies. What further throws one off is the fact that there is a lot of intended comedy in the film, which has not one, but two comedic sidekicks who spend much of the film hamming it up. Spoofs generally work best when played straight, while more seriously intended movies often insert comic sidekicks to liven things up. There are moments when the film feels like a spoof – in particular Zsa Zsa Gabor seems to have fun playing a sort of caricature on her public image. But most of the time, the film simply feels like another rehash of Cat-Women of the Moon.

It’s clear that the film is not to be taken seriously. Charles Beaumont was a much better writer than this, as was Edward Bernds. But Queen of Outer Space does not work as spoof, nor as a “straight” comedy either. It is simply too inept on all levels to achieve anything it wants to achieve, whatever that may be.

You can nitpick the script, the dialogue and the production in infinity. There is little logic to the proceedings, and the science is truly bonkers. The men are hailed as heroes at the end of the film, but in reality they have done absolutely nothing. They are captured and imprisoned twice, and three times, and each time they are saved by the women. They fail to talk their way out of their predicament, fail to seduce the queen, fail to find the disintegrator ray and fail to capture the queen. The women, on the other hand, break the men out of prison, outsmart the queen’s guards and sabotage the disintegrator ray – thus saving the Earth – all on their own. If one is generous, one might concede that the men at least manage to be unwitting distractions, perhaps allowing the women to work their revolution while the queen focuses on the dumbfounded males. If this is intended as a film portraying how bad women are at ruling, then it achieves the exact opposite.

But nitpicking feels but it feels like a pointless exercise. The movie is well aware of how bad it is, but for some inexplicable reason the people behind it thought it was a good idea to make it anyway. It probably made its budget back at the box office, and I suppose that was really all that counted. Today it is fun to watch it as a so-bad-it’s-good movie, but that’s really all there is to it.

Acting-wise, there is nothing much to write home about here. Eric Fleming and Paul Birch could be good on a good day, but Fleming mostly acts as if he has a broomstick stuck up his derriere and Birch seems mildly confused throughout the movie. Laurie Mitchell is the most impressive as the evil queen Yllana, able to emote and bring weight to her role even though she does most of her acting behind a mask. Zsa Zsa Gabor plays herself, as she did in all of her films, and while she had little acting talent, she was always had that charismatic draw which made her interesting to watch on screen.

Reception & Legacy

Queen of Outer Space was released in the US in September, 1958, and played in some areas on a double bill with Frankenstein 1970 (review). I have not found any box office numbers, but the movie undoubtedly made its budget back.

US trade papers were generally amused, highlighting the film’s elements of spoof and humour, as well as the colour photography and its sexploitation potential. The Film Bulletin, for example, wrote: “Properly sold, it should intrigue the outer space fans and the male oglers as well. Grosses might be surprisingly strong.” Harrison’s Reports wrote: “what makes it somewhat more entertaining than other pictures of its type is that it has been endowed with glamorous girls and considerable light humour”. Variety said that “Ben Schwalb’s production is a good-natured attempt to put some honest sex into science-fiction and as such it is an attractive production”. British Monthly Film Bulletin gave the movie a middling 2/3 rating, writing: “The stylised settings, costumes and effects are shot in shiny space-colour. Otherwise this is an amiable, if rather tame burlesque of science fiction formulae.”

Charles Stinson gave the film a positive review in The Los Angeles Times: “Queen of Outer Space […] is not science fiction. Because if it were, it would be horrid. However…it is an elaborate parody of science fiction and, as such, it is quite good, indeed. […] Naturally, the one and only Zsa Zsa Gabor is the principal attraction. She comes through superbly, demonstrating a nice touch for light, dotty comedy, as, with hair gone moon-platinum, she floats about gauzily, tongue in cheek, flirting outrageously, satirizing herself and sighing deeply over the fact ‘zat de qveen vil destroy ze planet Earss unless ve stop her, Capt. Patterson’”. Marjory Adams at The Boston Globe called the film “merry spoof of science fiction” with dialogue “of the sort which might be written by a high school freshman”.

One organisation that did not find the film amusing was the National League of Decency, that complained about the picture’s “suggestive costuming”.

In Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren opined that “Queen of Outer Space deserves some points for trying to make fun of a science fiction subgenre, but it just didn’t have the resourses”.

My two house gods in the realm of online science fiction movie criticism, Glenn Erickson and Richard Scheib, are not kind to this picture. Erickson writes at Trailers from Hell: “clever spoof comedy requires thought, timing and a production that isn’t rushing at warp speed to get scenes in the can. […] Queen of Outer Space […] is a silly story about court intrigues on the planet Venus, showcasing attractive Venusian showgirls. Randy Earth spacemen dish out bad jokes that hit new heights of sexism. […] It’s one thing to make fun of an underachieving picture that’s trying to float a serious story, but this strange item really doesn’t know what it is. It’s packed with verbal jokes but the only fun is laughing at the movie, not with it.” Scheib, at Moria, gives the movie a 0/5 rating, and is especially vitriolic about its rampant sexism: “Beauty, stupidity and willing subservience, that was what men wanted of women in the 1950s. The film makes the point as clearly as possible.”

Cast & Crew

Director Edward Bernds had a somewhat unusual path to becoming a movie director. Born in 1905, he became a ham radio operator in his teens, and was able to get a commercial broadcasting license in the early twenties. In 1923 he found employment as chief operator on one of the many radio stations that were popping up, and when the talking movies arrived, he was one of many radio operators who moved to Hollywood to work as sound technicians in 1928. At Columbia he worked as a sound engineer until 1944, until he asked for the chance to direct — his first commission was a 1944 edutainment short for the war service, and his first entertainment films were short films featuring comedian El Brendel and The Three Stooges in 1945. He considered his second Three Stooges short The Bird in the Head (1946) his true crash course in directing. It was filmed shortly after Curly had his stroke, and Bernds quickly realised that the former star was in no shape to perform his old gags, so he had to think on his feet and rewrite the movie so it covered up Curly’s disability while still keeping him the main character. Apart from the dozens of short films he made with The Three Stooges, he also directed three feature films with them between 1951 and 1962.

In 1948 Edward Bernds got his first shot at directing a feature film, when he was contracted to take over the direction of Columbia’s hugely popular Blondie comedy film series about the Bumstead family. Between 1948 and 1950 he directed the five last films in the series. He was also commissioned to direct another comedy film series based on a comic strip, Gasoline Alley, which ended up being only two movies long. Moving to Allied Artists in 1953, he took over another hit series, The Bowery Boys, with whom he made eight movies with over three years, including the horror comedy cult classic The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1955). At AA, he also branched out from comedy to other genres — straight westerns, melodramas, action thrillers, even a hockey movie. Apparently his contract with AA wasn’t exclusive, and on the side he branched out into TV and worked with other low-budget companies, particularly Regal Pictures and API, for whom he made a string of teensploitation movies. 1955–1960 was a mishmash of low-budget movies: comedies, teensploitation, crime dramas, action films and a couple of science fiction movies. In 1958 he directed Space Master X-7 for Regal and Queen of Outer Space, starring Zsa Zsa Gabor, for AA. He is probably best known to genre fans as the director of the sequel Return of the Fly (1958), with Vincent Price returning as the co-lead. And in 1961 he directed the cult movie Valley of the Dragons for Al Zimbalist. Another milestone, or perhaps more a gravestone, for his career, was that he wrote the script for Elvis’ 1965 movie Tickle Me, which was his last official screen credit – the film helped save Allied Artists from bankruptcy.

Charles Beaumont was a much better writer than his script for Queen of Outer Space (1958) would suggest. Born in 1929, he was active as an author, screen- and television writer between 1950 and his tragic death in 1967. Specialising in a unique blend of horror, science fiction and fantasy, his stories inspired numerous other authors, and beside Rod Serling, he was the most important creative force behind the TV show The Twilight Zone in the 60s.

Born Charles Leroy Nutt in Chicago, he worked under a few pseudonyms before settling on Charles Beaumont, which he also adopted as his legal name. He published his first short story in Amazing Stories in 1950, and in 1954 Playboy chose one of his stories as the first fictional short story to be published in the magazine. His first TV credit in 1954 was not for a script, but for a story, Masquerade, about a killer stalking a masquerade, inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of Red Death, for Four Star Playhouse. He started writing for TV proper in 1957, adapting his own story, Face of a Killer, for the small screen. His first big screen credit was for Allied Artists’ science fiction clunker Queen of Outer Space (1958), starring Zsa Zsa Gabor – a script which he reportedly wrote as a spoof, but which was too subtle a spoofing for the director to detect, with disastrous results, when the director attempted to spoof up the spoof.

In 1959 Beaumont became a sought-after TV writer, writing for both western and detective shows, but especially wanted for his horror, science fiction and fantasy teleplays. This was the year that Rod Serling premiered his groundbreaking show The Twilight Zone, and Beaumont was on board from the beginning to the original series’ conclusion in 1964, penning at least 22 teleplays, many of them among the best-regarded. Among the episodes he wrote were “The Howling Man”, about a prison inmate suspected to be the devil, “Static”, in which a radio functions as a time machine, “Miniature”, in which a man falls in love with a figure in a dollhouse, “Printer’s Devil”, in which the devil takes a job at a newspaper, and the dystopian “Number 12 Looks Just Like You”, imagining a world in which everyone’s brains are transplanted into the bodies of supermodels.

In 1962 Beaumont struck up a fruitful collaboration with Roger Corman, as Corman was moving away from his ultra-cheapos to slightly more ambitious projects, including his Edgar Allan Poe cycle. Beaumont, well-versed in all things Poe, co-wrote the scripts for The Premature Burial (1962), The Haunted Palace (1963) and The Masque of Red Death (1964) – but also a very different Corman film, the anti-racist movie The Intruder (1962), starring William Shatner, and, despite being one of Corman’s few financial failures, consider one of his best films. Beaumont also worked on two films for George Pal: The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) and 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964).

But around 1963, Beaumont was struck by a mysterious illness which affected his brain, and appeared to age him rapidly and affected his ability to speak, remember, concentrate and write. Although doctors were never able to confirm what it was, some suggested it might have been a combination of Alzheimer’s Pick’s Disease. Beaumont was not only writing film and TV scripts, but also short stories for different magazines, and the disease severly hampered his ability to keep up with all his writing obligations. As the illness progressed, he started collaborating ever more with other writers who were friends of his, and who eventually started ghost writing for him. After 1965 he was unable to write for TV or film anymore, as his brain didn’t allow for the fast-paced rewrites and changes demanded by the medium. Beaumont passed away in 1967, only 38 years of age. A few of his short stories have been turned into TV episodes after his death. Most interesting, however, is the Roger Corman-produced Brain Dead – released in 1990 as a sort of Nightmare on Elm Street clone, but co-written by Beaumont. The film was based on a script that Beaumont had delivered for Corman in the 60s, and that had been sitting in his desk for decades, and that suddenly became thematically relevant with the success of the Elm Street movies. It is generally considered one of Corman’s better 80s/90s movies, and should not be confused with Peter Jackson’s zombie splatter film Braindead (1992).

Little biographical informaton is available online for producer Ben Schwalb. He was born in Riga, Latvia, in 1901, and immigrated to the US sometime before 1929, possibly around the time of WWI. He seems to have worked in some capacity behind the camera in Hollywood in the late 20s – his first IMDb credit is as production manager in 1929. He directed and/or produced a long string of short films for Columbia in the late 30s and early 40s, after which there is a nine-year gap in his IMDb credits, possibly due to serving in the US army, possibly in its film department. He next turns up as a feature film producer at Monogram in 1951, right on the cusp of the studio’s rebirth as Allied Artists.

Schwalb would remain with Allied Artists until the studio ceased its movie production in 1966. In the 50s he was put in charge of the popular Bowery Boys comedies, producing several dozen of them with directors William “One-Shot” Beaudine, Edward Bernds and Jean Yarbrough, including The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954), which remains the most popular of the 48 Bowery Boys pictures produced between 1946 and 1958. After the demise of the franchise, Schwalb became an all-round producer, making crime dramas, westerns and comedies – but also a few science fiction and horror movies: The Disembodied (1957), Queen of Outer Space (1958) and The Hypnotic Eye (1960). In 1965, when Allied Artists was on the verge of a bankruptcy, the studio decided to put all its eggs in one basket, and convinced Col. Parker to let them produce an Elvis Presley movie, Tickle Me. Its $1,8 million budget was far beyond the typical AA production, and of that, $750,000 was made up of Elvis’ acting fee, and he also received 50 percent of the film’s profits. Heading up the production was Ben Schwalb. The movie eventually made $3.4 million domestic box office gross, and well over $1 million abroad. Tickle Me briefly saved Allied Artists from a bankruptcy, but the studio nevertheless had to cease its movie production in 1966. Tickle Me was Ben Schwalb’s last film.

Zsa Zsa Gabor is a legend, the original socialite superstar, the Paris Hilton of the 40s, 50s and 60s – in fact she was even married to Paris Hilton’s great-grandfather, hotel magnate Conrad Hilton – one of her nine husbands. Born in 1917 in Budpest in the Austro-Hungarian empire to moderately wealthy bourgeois parents as Sari Gabor, she struggled to pronounce her own name as a child, leading to her nickname Zsa Zsa. In 1933 she was the second runner-up in the Miss Hungary pageant, and then embarked on a modest stage career in Vienna and Budapest. Of Jewish ancestry, she fled to the United States in 1941, and was soon followed by the rest of her parents, including her sisters Eva and Magda. The three sisters quickly made a splash in the American social scene.

Merv Griffin, who dated Eva Gabor for some time, later wrote: “All these years later, it’s hard to describe the phenomenon of the three glamorous Gabor girls and their ubiquitous mother. They burst onto the society pages and into the gossip columns so suddenly, and with such force, it was as if they’d been dropped out of the sky.”

The Gabor sisters were independent, ambitious and intelligent enough to play their roles as “noble” European glamour girls with a wink and smirk, always able to laugh at their own public images – Zsa Zsa perhaps better than any of them.

Sza Sza Gabor made her film debut in 1952, and the same year was cast in what was perhaps her most demanding, and and best, performance, as the female lead in John Huston’s Moulin Rouge. Huston later described her as a “creditable actress”. In 1953 she made a detour to Europe, appearing in a handful of French and German films, before returning to the US, where she appeared in several TV shows and a number of movies – mostly of the B variety. On the serious side, she played a supporting role as a murdered spy in the the crime drama Death of a Scoundrel (1956) and had a small but memorable role as a strip-club owner in Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). But she also appeared in her share of more absurd outings, for example Albert Zugsmith’s bonkers cold war drama The Girl in the Kremlin (1957) about Josef Stalin having had plastic surgery and living in the US, in which Gabor played the titular girl. She also appeared as the leader of a rebellion on the all-female planet on Venus in Allied Artists’ campy Z-grader Queen of Outer Space (1958).

By the 60s, Zsa Zsa Gabor was mostly doing TV guest spots and cameos, often playing herself, or a version of herself, as in Bert I. Gordon’s inept horror movie Picture Mommy Dead (1966), Ken Hughes’ crime conedy Drop Dead Darling (1966). Frankenstein’s Great Aunt Tillie (1984), A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987), The Naked Gun 2½: The Smell of Fear (1991), The Bevery Hillbillies (1993) and A Very Brady Sequel (1996), which was to remain her last film appearance. In addition to her acting career, Gabor appeared in over 200 TV shows and TV specials as a guest, interviewee, host or participant.

Zsa Zsa Gabor’s numerous adventures in the social life of America is perhaps best told somewhere else. She suffered numerous health issues in her later years, died in December, 2016, two months before her 100th birthday, leaving her sprawling Bel Air mansion to another notorious socialite, longtime husband, Frédéric Prinz von Anhalt.

The male lead in Queen of Outer Space (1958), Eric Fleming, liked gambling. He underwent reconstructive surgery to his face after failing to lift a 91 kilo weight as a bet in the army. The weight dropped on his face. He got into acting when working with construction at Paramount, and lost a 100 dollar bet with an actor, claiming he could do a better audition that the actor. After losing 100 dollars to acting, he decided to make it back on acting and started taking acting lessons. From 1951 to 1954 he appeared only in a few TV productions, but got his big break when being cast as a co-lead in George Pal’s science fiction extravaganza Conquest of Space (1955). However, as the film flopped at the box office, it did little good for his career, and he continued appearing in TV guest spots and in a few B movies, such as the sci-fi film Queen of Outer Space (1958) and the horror Curse of the Undead (1959). Better fortunes loomed in 1959, when he was cast as the co-lead in the long-running and very successful western series Rawhide, alongside Clint Eastwood. Tragically his career, and life, was cut short during the filming of a jungle adventure movie in Lima, Peru in 1966, after he had left Rawhide. During a scene on the Hullaga river, Fleming’s canoe was overturned, he was swept away in the rapids and drowned.

Stocky, barrel-chested co-lead in Queen of Outer Space, Paul Birch, was an original member of the Pasadena Playhouse stock, and worked as an acting teacher. On the side of his stage career he appeared in 39 films and was a popular guest star on over 100 TV shows between the mid-forties and late sixties. His first brush with science fiction came in 1953, when he was among the first to be disintegrated in George Pal’s The War of the Worlds (review). In the mid-fifties he became part of Roger Corman’s stock company. Corman gave him leading roles in all the three SF movies he appeared in. He played the family father fighting the alien in The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955, review) and the stern former military man who runs the safehouse in Day the World Ended (1955, review). His most memorable role is perhaps that of the alien “vampire” with white, hypnotic eyes that takes up residence in a Hollywood mansion and drains humans of their blood in order to fight his race’s blood disease in Not of This Earth (1957, review). Other SF films he appeared in was Columbia’s The 27th Day (1957, review), where he had a supporting role as an Admiral, and Allied Artist’s Zsa Zsa Gabor vehicle Queen of Outer Space (1958), in which he played Professor Konrad.

Dave Willock, playing the “straighter” of the comic sidekicks in Queen of Outer Space (1958) was a perennial support player who showed up as pleasant, jovial bit-part characters in over 200 films and TV shows big and small between 1939 and 1983. In his later career, he was a favourite of Robert Aldrich, Jerry Lewis and Disney. He can been seen, briefly, in numerous science fiction movies, including It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), Revenge of the Creature (1955, review) and The Nutty Professor (1963). His role as one of the four crewmen who land on the all-female planet of Venus and hook up with Zsa Zsa Gabor in Queen of Outer Space (1958) was probably the biggest part of his career. The same thing can be said about the fourth and last crewman in Queen of Outer Space, Patrick Waltz. Between 1950 and 1971 Waltz portrayed a library of bit-parts in film and TV, often sailors, soldiers and policemen. Queen of Outer Space was probably the closest he ever got to playing a romantic lead.

Laurie Mitchell gives perhaps the best performance in Queen of Outer Space as the titular evil queen. Born Mickey Koren, she was a juvenile model before entering acting under the moniker Barbara White, both in Playhouse theatre and in small roles in film and TV in the mid-50s. Her first movie role was as one of the pleasure girls accompanying Kirk Douglas in the beginning of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954, review). In 1957, after minor roles as barmaids and “girls” she dyed her hair blonde and took a new moniker, Laurie Mitchell. She was then cast in a co-starring role in Allied Artists’ teen musical comedy Calypso Joe (1957), which evidently caught the eye of AIP, casting her as one of the principle lilliputian cast in Bert I. Gordon’s Attack of the Puppet People (1958. review). Later the same year, Allied Artists again took advantage of her talents, casting her as Queen Yllana of Venus in Queen of Outer Space. Almost back-to-back, she filmed Richard E. Cunha’s Missile to the Moon (review). Both films were basically remakes of Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review). This was the nadir of Mitchell’s movie career, although she carved out a decent career as a TV guest performer in the 60s and 70s.

The three ladies playing the principle rebel Venusians and the romantic foils for the crewmen in Queen of Outer Space were not merely pretty faces, but accomplished actresses.

Lisa Davis, a UK-born child actress, originally came to Hollywood to audition for the title role Disney’s planned live-action adaptation of Alice in Wonderland in 1951 – a movie that was never made. However, she remained in Hollywood and appeared in TV shows and B-movies, including a couple of leads in low-budget westerns for United Artists in the late 50s. She is fondly remembered as Motiya in Queen of Outer Space (1958), but best known for her voice role as the kindly Anita Dearly in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) – she finally got her Disney appearance. She was originally offered the role or Cruella De Ville, but declined because of her love for dogs.

Barbara Darrow was born into a showbiz family, her mother and uncle were actors and her dad a movie landscape artist. Her sister Madelyn was an occasional actress and model – best known for being the face of Rheingold beer. Barbara’s son later became the president of Columbia Tristar Television and produced Two and a Half Men. Her husband became founding president of Viacom. Darrow was a a talented actress who never really got a break, she appeared in around half a dozen B-movies in the 50’s, perhaps best known for replacing Marla English at the last minute opposite Spencer Tracy in The Mountain (1956), and for appearing briefly but memorably in The Monster That Challenged the World (1957, review), as the first victim of the giant slug. She was even featured on the poster as the girl in a bathing suit getting carried off by the monster. A slightly bigger, but more anonymous role, was as one of the four Venusian rebels who get friendly with the crashed Earth crew in Queen of Outer Space (1958).

Model and actress Marilyn Buferd was crowned Miss America in 1946. She made half of her around 20 movies in Italy and France, working with her Italian movie producer husband Franco Barbaro. She appeared in The Unearthly (1957, review) and Queen of Outer Space (1958), her last movie.

There are several slightly interesting actresses to pick out amongst the rest of the Venusian cast. Laura Mason didn’t quite have a stellar movie career, but appeared in around 30 movie bit-parts and TV guest spots between 1942 and 1969. The most interesting detail of her career, however, is that in her first five movies she appeared as a tag-team with her twin sister, Jean Romer. Best known of their performances is that as Siamese twins in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942). Little information of them is available online, and no movie databases or websites can confirm whether they were actually twins. IMDb doesn’t even have a birth date for Romer. However, a detective at the DeathList Forums does claim to have information that they were really twins, and that Laura Mason was born Lillian Romer and Jean as Jeanne Lisa Romer, and that both were born on August 10, 1924 – a birth date that IMDb also lists for Mason.

Lynn Cartwright was an acting student in New York when she met ex-con and later heavy actor Leo Gordon. The couple moved to Hollywood when Gordon found an acting agent, and soon started getting good roles. However, Cartwright struggled on in minor TV guest spots. Her career took a slight turn upwards when Gordon started working as a screenwriter, and was able to get her cast in small and sometimes even larger supporting roles in his films. But even in low-budget movies like Queen of Outer Space (1958) and The Wasp Woman (1959), she was tucked away in minor parts. She got few roles in the 60s, but made a “comeback” in the 70s, working primarily in super-low-budget sexploitation movies, and she became a favourite of cult director Rod Amateau – although she still appeared mostly in roles such as “assistant”, “secretary”, and the like. She appeared as just such an assistant in the infamously bad Robert Vaughn no-budget schlocker The Lucifer Complex (1978) and in another small role in Amateau’s baffling Nazi comedy Son of Hitler (1979), with Peter Cushing. In 1992 she got a surprisingly dignified ending to her career, as she appeared in the final scene of the baseball classic A League of Their Own – as the older version of Geena Davis‘ character, a role she got for her uncanny resemblence to Davis.

An actress of some note was Joi Lansing – an immensely popular pinup model since the age of 14, who attended MGM’s talent school in the late 40s. She made her film debut in 1947 and appeared in over 100 films or television shows before she became ill with breast cancer in 1970. She died in 1972, only 43 years old. Throughout her career she combined her modelling with mostly minor film roles and TV guest spots. With her well-endowed figure and blonde hair, she often competed for roles with Jayne Mansfield and Mamie Van Doren. However, as opposed to many of her modelling sisters trying their luck on screen, Lansing occasionally showed that she actually had some acting chops as well. Still, her leading lady parts were few and far between, and confined to B-movies such as the crime film Hot Cars (1956), the musical horror comedy Hillbillies in a Haunted House (1967), with a an all-star B-movie cast consisting of John Carradine, Lon Chaney Jr. and Basil Rathbone, as well as the monster movie Bigfoot (1970), again with Carradine. This was her last film. However, her most famous scene is a brief but memorable one. She had a large part in the legendary tracking shot in the opening of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958), in which she plays the the dancer who dies in a car explosion at the end tracking shot, after exclaiming to a border guard “I keep hearing this ticking noise inside my head!” She was also fourth-billed in the SF movie The Atomic Submarine (1959). However, he greatest fame came from appearing in a recurring role in around 125 episodes of The Bob Cummings Show between 1955 and 1959.

Janne Wass

Queen of Outer Space. 1958, USA. Directed by Edward Bernds. Written by Charles Beaumont & Ben Hecht. Starring: Zsa Zsa Gabor, Eric Fleming, Paul Birch, Laurie Mitchell. Dave Willock, Patrick Waltz, Lisa Davis, Barbara Darrow, Marilyn Buferd, Laura Mason, Lynn Cartwright, Matjorie Durant, Joi Lansing, June McCall. Music: Marlin Skiles. Cinematography: William Whitley. Editing: William Austin. Art direction: Dave Milton. Makeup: Emile LaVigne. Special effects: Milt Rice. Visual effects: Jack Cosgrove. Produced by Ben Schwalb for Allied Artists.

Leave a comment