What happens when an altruistic scientist’s brain is placed in a monstrous metal body without a heart? The not too surprising answer is to be found in Paramount’s curious but overrated 1958 B-movie. 4/10

The Colossus of New York. 1958, USA. Directed by Eugene Lourié. Written by Thelma Schnee, Willis Goldbeck. Starring: John Baragrey, Mala Powers, Otto Kruger, Ross Martin, Charles Herbert, Ed Wolff. Produced by William Alland. IMDb: 5.9/10. Letterboxd: 3.1/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Returning from Sweden, where he as been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his scientific efforts to battle food scarcity, brilliant, caring and humble Dr. Jerry Spensser (Ross Martin) is hit by a truck and killed instantly. His father, brain surgeon William Spensser (Otto Kruger) rushes him to his lab, and locks the door. Hours later he informs Jerry’s friends and family that he was not able to save him.

This the dramatic beginning of The Colossus of New York (1958), produced by William Alland for Paramount, and directed by Eugène Lourié. It is remembered as Hollywood’s first cyborg movie, and is often quoted as one of the better science fiction B-movies of the late 50s.

Jerry leaves behind his brother Henry Spensser (John Baragrey), himself a brilliant electrical engineer, who has always stood in the shadow of his genius brother, a wife, Anne Spensser, (Mala Powers), a son, Billy (Charles Herbert), and a best friend, Dr. John Carrington (Robert Hutton). Together, they try to pick up the pieces and move on.

All but Henry, whom father William takes into his confidence, and reveals that Jerry is not dead at all – only his body. His brain lives on in a vat, waiting for a new mechanical body, that William hopes that Henry will be able to construct. Everything that makes a man who he is, is his brain, says William, and by building a mechanical body for Henry, he will be able to complete his work with ending world hunger. At first, Henry is appalled at the idea. “That is not Jerry”, he insists: a brain without a body that cannot feel warmth, cold or pain, that cannot be near the people it loves, is not a human being, and will end up a monstrosity. But William insists that all that is Jerry is inside his brain. Jerry was a true altruist, and would wish to continue his work for the good of humanity, even though he could never again be with his child and wife, even if he could never again feel and live a normal life. Not entirely convinced, Henry agrees to make a body for his brother, but only on the condition that Jerry must have a choice.

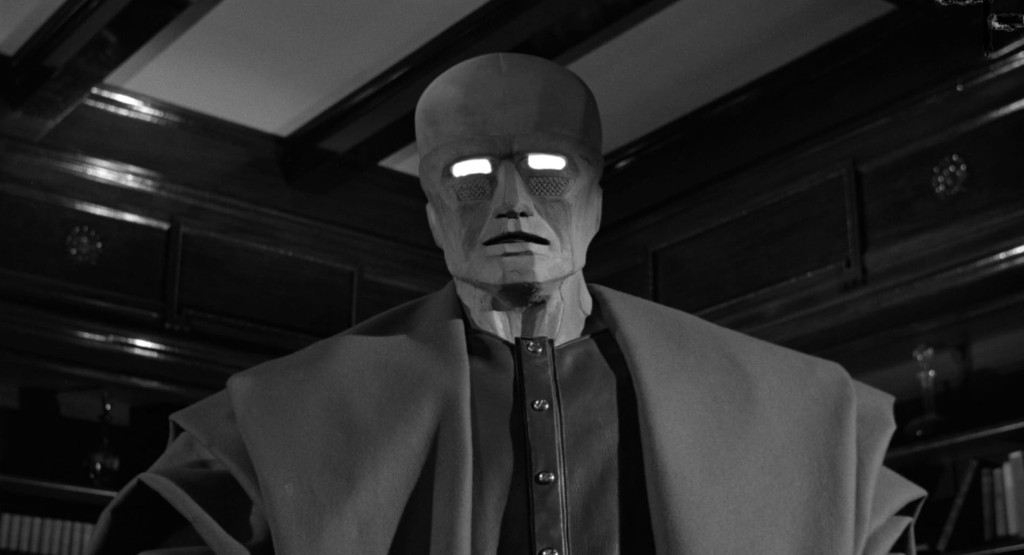

It is around the halfway mark of the 70-minute film that we first meet the Colossus of New York, an eight-foot mechanical monstrosity with blinking lights for eyes, electrical crackling when his brain is working, and a mechanical voice. When Jerry is first awakened, he is aghast and tells his father to destroy him. But William convinces him to carry on with his work, despite the discomfort and sorrow.

Work goes well, but soon troublesome features emerge that are wholly inconsistent with the peaceful, loving Jerry. The Colossus becomes irritable, stingy and threatening, and is kept in check only through the kill switch that William has designed. Against the wishes of William, Jerry leaves the lab and visits his own grave, where he meets his son Billy, who thinks he is the gentle giant. However, his wife Anne also catches a glimpse of him, and becomes obsessed with the giant monster.

Back at the lab, Jerry has gone through a complete personality change. No longer does he want to help the needy, but destroy them, so that the world can be inhabited by the strong, and ruled by the mechanical monster itself. He destroys William’s kill switch and smashes all his research into ending world hunger. He vows to eliminate all scientists who used to be like him, who prop up the weak and needy of the world.

Billy and the Colossus meet several times, and soon Jerry asks his son to call him “dad”. Meanwhile, Henry falls in love with Anne, and unfortunately for him, his brother catches him in the act of kissing her. This is the last straw for Henry, who wants to take Anne away from New York. In reality, Anne seems to be more interested in Jerry’s old friend John. Hypnotising William with his eyes, the Colossus gets William to lure Henry to a meeting where the Colossus shoots death rays from his eyes and kills his brother. The same night, The rest of the family go to a function at the UN building. The Colossus enters on the balcony in front of the “Swords into Plowshares” mural, and starts killing scientists with his death rays. But Billy runs up to him and tells him to stop. Jerry says that he hasn’t got it in him to stop – but that Billy can stop him by pulling his destruction crank under his coat. Said and done, Billy gives his father the mercy kill. William muses that Henry was right all along, the brain needed the body. And presumably, with both brothers dead, Anne will now hitch up with John, as there is no other reason for him to be in the film.

Background & Analysis

The Colussus of New York is generally regarded as a better-than-average late 50s science fiction B-movie, and some critics find it both moving and poignant. I have my reservations about this, but we’ll get to that further down.

Major studios had a somewhat schizophrenic relationship with science fiction in the 50s. Generally considered the stuff for kids, sci-fi films were more or less taboo in Hollywood after the financial failure of the the ill-conceived SF musical comedy Just Imagine (review) in 1931. Major studios ventured into SF territory only when the genre was coupled with a horror theme during most of the 30s and 40s. However, the success of low-to-mid-budget productions like Destination Moon (review) and Rocketship X-M (review) in 1950 coaxed the majors into trying their hands at science fiction with a couple of decently budgeted, successful productions. However, studio brass never understood the genre, didn’t hire proper science fiction screenwriters, misunderstood the target audience and often bungled the marketing, leading to them abandoning science fiction as unprofitable in the middle of the decade. But then along came little, scrappy American International Pictures and created a low-budget formula for tapping into the teen market with sci-fi and monster movies, to great audience success and good profit. It took the majors a couple of years to realise what was going on, but when they saw the numbers from AIP, many of them wanted back in. One of them was Paramount, who in the late 50s produced a handful of interesting low-budget SF pictures.

One of these films was The Colossus of New York (1958). Generally, when writing about Hollywood low-budget science fiction films, I can rely on the excellent interviews conducted by Tom Weaver with the cast and crew of the movie. However, in this case, Weaver writes in the foreword of his book It Came from Horrorwood, none of the four people involved with the movie he interviewed could remember anything about the production by the time Weaver got around talking to them. However, Bill Warren has been able to dig up an interview with director Eugène Lourié from Fantastic Films magazine from 1980, when he apparently had a little more recollection of the process.

Lourié was a French production designer who started his career in France, and is best known for his numerous collaborations with Jean Renoir, and has frequently been cited as one of the best in the business. After relocating to Hollywood, he occasionally sat in the director’s chair as well, and is particularly known for having directed The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), in collaboration with Ray Harryhausen, the film which served as a blueprint for all 50s giant monster movies.

Producer William Alland had had a great run with director Jack Arnold, producing pretty much all of Universal’s science fiction movies during the first half of the decade. By the late 50s he had jumped ship to Paramount in hopes of bigger budgets, only to find, to his disappointment, that he was given even less leeway at the bigger studio. Alland was something of an ideas man, and it is possible that he came up with the pitch for the film, even if the story is credited to Willis Goldbeck, a screenwriter who was capable of good work, although had no experience with science fiction. According to Alland, the idea for the film was taken from Paul Wegener’s 1920 movie The Golem, about the mythical Jewish guardian/monster conjured forth from clay. Lourié says that he liked the idea of modern recreation of the golem myth, but thought that the finished script was terrible. He considered pulling out of the movie, but as it would only entail an 8-day shooting schedule, he decided to just get it over with and grab the money.

The actual script was written by later parapsychology researcher Thelma Moss, credited with her maiden name Thelma Schnee. In it one can see three major influences: The Golem, Frankenstein and Donovan’s Brain.

The Golem of Prague is a 19th century German narrative, set in 16th century Prague. Many different authors have created different narratives for the story, but all involve a fictionalised version of Rabbi Loew using texts from the kabbala in order to create a giant man out of clay to protect the Jews of Prague against blood libel. The golem is activated by placing a scroll containing the secret name of God, a shem, either in the mouth or the forehead of the golem, and deactivated by removing it. The most often repeated version has the golem malfunction and go on a rampage, before the rabbi is able to remove the shem. The golem is invariably described as being between 230 and 280 cm tall, having superhuman strength, and being mute.

In The Colossus of New York, father and son Spensser essentially create a golem, not with magic and clay, but with science and electronics. Instead of a shem, they have not one, but two kill switches – one remote for putting the golem to sleep, and one crank in its side, which kills it. Like the golem, the colossus is created for good deeds, but malfunctions and goes on a rampage. In particular, the film shares many similarities with the German 1920 movie The Golem. For one thing, both the golem and the colossus intervene in a romantic triangle drama and kills one of the suitors of the maiden of the story. In the 1920 film, the golem is possessed by the demon Astaroth, and in the movie by the deranged and jealous brain of Jerry Spensser. A direct lift from The Golem is the fact that in the end, the monster is killed by an innocent child.

But when it comes to the film’s theme, it is more closely related to Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein, or even more so Universal’s 1931 movie (review) – itself inspired by Wegener’s 1920 movie. It’s the classic theme of the monster turning on its creator, in particular the the first scenes with Jerry as a cyborg echo the literary Creature’s pained lamentation over having been created against its will. There are many visual nods to James Whale’s film – the huge, clumsy colossus clearly takes its inspiration from Boris Karloff’s creature, and several scenes are callbacks to Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review): the scene in which the colossus takes its first steps, the one in which it carries the heroine of the film in its arms, and not least the scene in which it first meets Billy – with strong visual connections to the Frankenstein scene with the creature and little Maria – with the exception that Billy survives the encounter. In both Frankenstein movies, the climax takes place in a high places. In the first one, the creature battles his maker in a burning windmill, and in the second, he blows himself up in Frankenstein’s tower. In The Colossus of New York, the cyborg rains death from a balcony – and the final moment when he asks Billy to shut him down could just as well be illustrated with Karloff’s final words in Bride: “You – live! We belong dead.”

And finally, of course, there is the inspiration of Curt Siodmak’s influential 1942 novel Donovan’s Brain, which by 1958 had already been the subject of two official adaptations and several “inspired” films. Siodmak’s novel concerns a scientist preserving the brain of a genius businessman in a vat, and the way in which the brain takes control of the scientist’s mind, using his body to carry out his criminal and murderous schemes.

The setup for the film is undoubtedly interesting, and it is easy to see why Lourié was attracted to it. This was the first Hollywood movie to tackle the case of the cyborg. While the brain transplant trope was already an old cliché, the idea of exploring the melding of man and machine was something new and exciting, bringing the Frankenstein trope into the atomic age. The premise opens up an opportunity to make a film which explores both the question of what it means to be human, and the notion of our growing dependence on technology.

However, Goldbeck and Moss’ script somehow manages to sidestep most of the interesting angles in the setup. The main takeaway from the movie seems to be that you shouldn’t transplant a human brain into a mechanical machine, because it will become evil without a human body. And unfortunately, that’s pretty much it. In a way, the film was very much ahead of its time – anticipating Robocop (1987) 30 years later. The heart of that film was Murphy struggling to regain his memory and his humanity, confronting the people that created him. Robocop played Murphy as the tragic hero of the story, and the reclamation of his humanity was the film’s payoff. Briefly, it seems as if The Colossus of New York would take the same route, but the script isn’t able to go there. Jerry turns evil long before he learns of his brother’s betrayal, and doesn’t seem at all that interested in taking revenge on his father, that created him. He never once has a conversation with his wife, a plotline that could have notched the film into a different gear. His sudden turn in the end also comes right out of the blue, with no build-up or precedent. He just suddenly realises the error of his ways when his son tells him to stop. Even more bizarre is the conclusion, when the father William, who has been set up as the real villain of the piece, just shrugs off the (second) death of his son, and the dozen people he has killed at the UN building, noting in passing that apparently he was wrong in thinking that one could transplant a brain into a machine. Apparently, the fact that William has created a killer machine will have no consequences.

The acting in the film is not a problem per se – most of the players in the film are competent. However, John Baragrey as Henry makes for a bland leading man, but to be fair, he isn’t helped by his character, who elicits little sympathy with the viewer. Mala Powers was a good actress, despite being stuck in B-movies for much of her career. She is fine as Jerry’s “widow”, but damsel in distress roles didn’t give ther the chance to play to her strengths. She was better as characters with more agency. Otto Kruger as father William was a fair character actor, but didn’t quite have the chops for mad scientist roles. Robert Hutton barely registers in the film.

The most compelling actor is Ross Martin as Jerry – who later found TV fame with The Wild Wild West. His bright and sprightly energy lights up the film during the brief moments he is on screen in the movie’s beginning. However, he disappears all too early, even if his voice is heard behind the metal monstrosity throughout the picture. Charles Herbert, one of the most popular child actors of the era, plays his role very much as he did in The Fly (1958, review). While he was critically praised for his work by conteporary critics, the sort of loud, over-acting style that was prevalent among child actors at the time is quite grating to a modern viewer.

One thing that makes this film interesting from a historical point of view, is that it marks the first Hollywood appearance, and perhaps the first ever screen appearance, of a cyborg. The history of cyborgs in fiction easily becomes confused, as terms like robot, android, bionic and cyborg are sometimes used interchangeably. According to a very unreliable Wikipedia list, the first fictional cyborg appeared in Samuel-Henri Berthoud’s short story Prestige in 1831, but since I haven’t read it or found any synopsis of it, I can’t vouch for the accuracy of this statement. However, the story that is generally considered as the one introducing the cyborg to popular consciousness is Edgar Allan Poe’s The Man That Was Used Up (1839), about a soldier so badly damaged during the campaigns against the Native Americans that he has to be assembled every day from prosthetics and mechanics. Like in Poe’s story, most early mentions of cyborgs in literature were humorous or satirical, and it wasn’t until around the 1920s that serious literature on the subject started appearing, by authors such as Maurice Renard, Francis Flagg and Edmond Hamilton. By the 50s, the concept was fairly commonplace in SF literature, but had yet to be explored on screen.

Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz (1939) is arguably a cyborg, but since the story plays out in a magical fantasy setting where magical fantasy rules apply, it is debatable whether he should be considered a true cyborg. Some identify Maschinenmensch from Metropolis (1927, review) as a cyborg, but she is quite definitely an android – or actually a gynoid, if you want to use the correct terminology. (Also, beware of AI-written articles like this, where nine out of ten mentioned “cyborgs” are nothing of the kind). Nitpicking and semantics aside, 1958 was most likely the year that the science fiction cyborg made its debut on the silver screen. Two films contend for the title: William Alland’s and Eugène Lourié’s The Colossus of New York and The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy (review). Which was first is a matter of which source you choose to believe. The Mexican film premiered in July 1958, and the US film has conflicting dates: Wikipedia states its premiere as June, 1958, while IMDb says November 1958. However, since it played on a double bill with The Space Children (review), it was probably released in June. Interestingly, both pictures include a human brain transplanted into a cumbersome robot.

The actual mechanical monstrosity of The Colossus of New York itself isn’t particularly novel. Tall, broad-shouldered, and with a mechanical “scar” around its head, it cuts a silhouette strikingly similar to Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein creature, an effect only strengthened with its slow, ungainly gait. It is, however, a clear improvement upon the many box-and-ventilation-tube robots that science fiction serials and movies had seen over the years. Of course, most of it is covered in clothing – including a gigantic cape. It begs the question why a robot/cyborg would need an overblown regal cape – or clothes at all – since it is solely designed to sit hidden in a laboratory. In fact, one wonders why Henry has bothered with its gigantic, hulking body, including arms and legs, in the first place, since it is Jerry’s mind the scientists are after. Why does it need to be able to walk? Of course, both questions have simple answers: the Colossus wears clothes because they are cheaper and easier to design and manufacture than a robot suit, and the Colossus is huge and walks because the filmmakers wanted to make a film about a huge walking robot.

According to Bill Warren, the face and hands of the Colossus were designed by the great Charles Gemora, while the rest was done by Ralph Jester. The Colossus’ motionless, almost noble face gives it a statuesque feel. The mouth is half-open and moves slighly when the cyborg is talking, giving it a slightly more interesting and life-like appearance than just simply a static face. The monster was played by 7’4 or 220+ cm tall actor Ed Wolff, and the Colossus’ height was further enhanced with platform boots and a tall head – there are grilles under the Colossus’ eyes, which were evidently added to the design for Wolff to be able to see through. Another reason the suit needed to be big was that it had to be functional – the lights in its eyes were practical effects, and this was still a time before LED lights and button-size batteries. Furthermore, the lights needed to have operational switches enabling them to be turned on and off in rapid succession. According to Warren, the total weight of the suit was 160 lbs, or over 70 kg. The suit also had moving mechanical parts, which required cables and mechanisms to be hidden. Plus: Wolff couldn’t breathe through the suit, which meant oxygen and air tanks also had to be concealed under it all. As such, the Colossus suit was a minor marvel for a low-budget film shot in eight days.

The special effects in the picture are good across the board, even if the low budget prevents anything particularly impressive. Their quality comes as no surprise once you learn that they were created by two of the best men in the business, Farciot Edouart and legendary John Fulton, who like Alland had jumped ship from Universal to Paramount.

Director Eugène Lourié, primarily an art director by trade, knows how to compose a shot and paint with light and shadows, and even at its brisk shooting pace, The Colossus of New York looks quite good. There are a few nice composite shots with the New York skyline in the background, and one memorable scene in which the Colossus emrges from the East river (critics like to point out that the Colossus is dry after having walked in the river, but from technical and safety reasons it is understandable that they didn’t want to drench the suit in water). The lab sets and mis-en-scene are also fairly interesting, in particular the brain-in-a-vat, with myriads of thin rods emerging from it, creating a novel picture, compared to similar scenes before.

The music in the movie is of some interest, as it is played only on three pianos. The score is credited to prolific composer (Nathan) Van Cleave, but according to Ted A. Bohus’ interview with Fred Steiner, it was a collaboration between Van Cleave and his protegé Steiner (known to fans of Star Trek and The Twilight Zone). According to Steiner, Van Cleave decided on the minimalist approach “largely because of the low budget”, but undoubtedly a Hollywood musicians’ strike at the time also figured into the decision. The music is atmopsheric and moody, and as Bill Warren puts it, “imaiganitive and intelligent, two qualities not otherwise applicable to the film”. Nevertheless, a haunting piano score is not the music of choice for a clunky B-movie about a murderous robot/cyborg, and it is often sorely out of sync with the images displayed on screen.

I have read several reviews and comments on The Colossus of New York that painted the film as a something a bit out of the ordinary, more of a thinking person’s science fiction movie, in comparison with much of the dregg that was being pushed out in Hollywood in the late 50s. Thus, my expectations when sitting down for this one were quite high, and unfortunately they were not met.

The premise opens up for exploration of several interesting themes, but the screenwriters somehow manage to miss all of them. It’s difficult to tell if it even explores a theme at all. That the movie’s massacre takes place at the UN building is surely no coincidence, and the setting leads one to surmise that the picture is trying to say something about cold war politics. But if the Colossus is the atom bomb, then it’s difficult to see how the rest of the story ties into it all. Is it about science? The punchline here is basically the same as in Metropolis (1927, review), that the heart must be the mediator between the head and the hand. So is this about war in general, or military technology? About international politics? A brain without a heart and a body will only lead to evil? Is it about compassion? Empathy in politics? The dangers of creating new technologies without ethical considerations? The curroption of power? It’s possible the film tries to make some or all of the above points, but the whole thing remains very opaque. Or perhaps it isn’t really trying to say anything else than that you should not transplant a human brain into a robot in an effort to solve the hunger crisis. Or at least you should refrain from giving it deadly laser eyes, as deadly laser eyes don’t really help much in solving the hunger crisis.

I can see how director Eugène Lourié would have initially been excited about the project, but then bummed out when he saw the script. The setup is promising, but the writing fails to take advantage of the possibilities, turning The Colossus of New York into a standard 50s monster romp. However, the film is well designed for a low-budget feature, and knowing everything that went into the cyborg suit, one cannot but be impressed by it. From a design standpoint, it also feels like it is trying to usher in something new to the screen, albeit heavily inspired by pulp cover art. Lourié’s direction is solid, but never quite outstanding. He knows how to paint a picture, but not alwys how to make the picture come alive. Producer William Alland, on the other hand, blamed the failure of the film on Lourié. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Alland says he “pissed it all away with his lousy direction”. However, in all fairness; while the direction could certainly have been improved upon, it is not this film’s main problem, which is the script.

The Colossus of New York is a fair late 50s sci-fi monster movie, but it’s clear why it hasn’t quite reached classic status even among 50s B-movie aficionados. It’s competently made, looks good for its budget and throws in a couple of nice ideas, which it, unfortunately, never gets around to exploring. One can admire Eugène Lourié’s atmospheric direction and the occasional poignancy of a few indivicual scenes, but his efforts are ultimately crippled by a screenplay that never reaches above the programmatic monster movie romp. This is all the more disappointing as it feels like a missed opportunity to do something out of the ordinary. It’s a fun watch for 50s science fiction completists, but no more than this.

Reception & Legacy

The Colossus of New York premiered in November, 1958, on a double bill with Jack Arnold’s The Space Children (review). Both films, produced for Paramount, has children as central characters – although in Colussus, the kid seems shoehorned into the story. The idea here was that children were the primary audience for science fiction movies, and that children wanted children they could identify with in the movies. Film critic and historian Bill Warren claims both assumptions were wrong. It was teenagers who were the main audience for science fiction, writes Warren – and furthermore, children weren’t necessarily intrerested in watching children on screen. For whatever reasons, the two movies didn’t actually play as a double bill, but were often attached as second features to other movies – perhaps Paramount didn’t think that The Space Children was strong enough for a top-billing.

The Colossus of New York received fair reviews in the trade press. Harrison’s Reports reported it as “no better and no worse than most science fiction program shockers that have flooded the market during the past year”. The magazine continued: “Although well produced, directed and acted, the story follows a familiar course and never quite succeeds in being really terrifying.” Variety opined that “Adults will probably find the [story] pretty hokey fare. However, [kids] will likely accept this William Alland production as an exciting 70 minutes”. Variety found Baragrey “somewhat wooden”, Kruger “inclined to be too glib” and noted that Powers had “little to do but look frightened”, but the magazine had some good words for Lourié’s suspenseful direction, as well as for the cinematography and special effects. It also noted Van Cleave’s minimalist score, writing: “it proves a lotta mood can be created by one instrument”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies (1984), Phil Hardy writes: “Lourié’s direction is juvenile, particularly when the monster is eventually subdued by Martin’s son, but the initial scenes of their meeting after the transplant have moments of real pathos”.

In his book Keep Watching the Skies, Bill Warren writes: “Some consider this William Alland production for Paramount an unsung classic, but I find it dry, ponderous and unoriginal […] Its monster-movie formula, low budget and lack of imagination combine to cripple the film.”

The Colossus of New York has middling-to-fair audience scores on popular platforms: 5.9/10 on IMDb and 3.1/5 on Letterboxd, as of writing.

Many modern critics find the movie laudable, and as Warren points out, consider it an unsung classic. In a 2011 review at the New York Post, Lou Lumenick writes: “It’s a oddball mash-up of Donovan’s Brain, Tobor the Great and Frankenstein that’s in equal measures cheesy and oddly affecting” and notes that “it plays better than it sounds”. At Slant Magazine (2012) Rob Humanick calls the picture ” a frequently overlooked classic in an oversaturated decade of monster movies, but one that nevertheless carries the torch from past landmarks like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to more recent entries like Source Code and RoboCop“. According to Humanick, the movie “is frequently threadbare and even a little silly, such as the scene in which Jeremy first discovers a romantic betrayal, but it stings like the best of them”.

Richard Scheib at Moria gives the film a good 3/5 stars, writing: “On a plot description level, The Colossus of New York is unexceptional but Eugene Lourie makes something extraordinary out of it directorially”.

Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant (2012) more closely echoes mine and Bill Warren’s sentiments: “Producer Alland was tasked only with producing an inexpensive horror attraction. Yet The Colossus of New York misses the boat for not exploiting the macabre situation of a man’s consciousness transplanted into another ‘body’. Good wife Anne never comes face-to-face with the new Jeremy, a confrontation that might have made Colossus a truly memorable fantasy.”

Cast & Crew

Producer William Alland and director Eugène Lourié are familiar to friends of 50s science fiction movies – for further information on their careers, click the above links. In short, Alland began his career as an actor and came up alongside Orson Welles at the Mercury Theater. His best-known role as a movie actor is as supporting character in Citizen Kane (1941) – and he played the second murderer in Welles’ murky 1948 adaptation of Macbeth. All in all, Alland only acted in 8 films. As a producer at Universal, Alland was one of the main architects of the resurgence of the monster movie and the path in which low-budget science fiction would take in the decade. It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), introduced the desert and the small American town as main stage for all sorts of science fiction shenanigans, and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review) revitalised the creature feature, and added another classic monster to the Universal roster. Tarantula (1955, review) is considered an all-time classic. However, as major studios lost interest in big-budget science fiction movies, and the emergence of successful no-budget monster movies made by studios like AIP and Allied Artists, Universal slashed Alland’s production budgets, and he was stuck with sub-par scripts and little time or money to realise visions. In 1958, Alland jumped ship to Paramount in hopes of more substantial budgets, but was sorely disappointed – he made the interesting but flawed double bill of The Space Children (1958, review) and The Colossus of New York (1958), before striking out as a freelancer. He only produced a small number of films before retiring in 1966.

No more important than Alland for the emerging monster movie genre in the 50s was Eugène Lourié. Frenchman Lourié primarily worked as a production designer, first in France, and from the 40s onward in Hollywood, where he immigrated with the outbreak of WWII. In France he was considered one of the country’s top production designers, and worked for directors like Max Ophüls, Marcel L’Herbier and Jean Renoir, for whom he designed the classics La grande illusion (1937) and La règle du jeu (1939). In the US, he continued his collaboration with Renoir, for whom he designed four American movies between 1943 and 1951. In 1951 he also worked as production designer on Charles Chaplin’s last film, Limelight.

However, for the science fiction genre, Lourié is primarily interesting as a director. His directorial debut was a low-to-mid-budget monster movie inspired by the massive success of the 1952 theatrical re-release ofKing Kong (1933, review) into theatres: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review). While dramatically not much above average, hampered by a thin and illogical script, the movie’s spectacular effects by Ray Harryhausen made it an enormous success both in the US and internationally. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms became the blueprint for the giant monster movie (replicated by William Alland on numerous occasions) and directly inspired Japanese studio Toho to produce Gojira (1954, review). The Colossus of New York (1958) was only Lourié’s second feature film as a director, although he did some work for TV. For his two final films as director, Lourié ended up – partly against his own wishes – recreating his magnum opus. He madeBehemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review) and Gorgo (1961) in Britain. Despite the fact that the films were both going to be somewhat different different, both ended up featuring a dinosaur-esque sea monster destroying London, because of pressure from producers. However, Gorgo, featuring a mother monster trying to save a baby monster from captivity, is generally considered one of the better efforts in the subgenre. After failing to break out of the shadow of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms as a director, Lourié decided to focus on his work as a production and art designer, which he did until the late 70s.

Among the actors, John Baragrey is first-billed. Baragrey was a respected character actor who occasionally got the chance to play romantic lead in film, however his bread and butter was the stage and TV. While mostly forgotten today, Baragrey was a noted TV performer, and president John F. Kennedy reportedly was a fan of his TV work. His movie output, however, is anonymous. Apart from his lead in The Colossus of New York (1958), he also appeared in the new American footage in Gammera the Invincible (1966).

Mala Powers was another respected actor who never achieved the higher echelons of stardom. She is best known for her appearances in one of her very first films, Cyrano de Bergerac (1950), and her two SF movie leads in The Unknown Terror (1957) and The Colossus of New York (1958). She got her bread and butter from guest spots in TV series. Powers trained under Michael Chekhov, and later in life taught the Chekhov technique and was the executor of the Michael Chekhov estate.

Otto Kruger is best remembered for his villaoinous roles in such prestige films as Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952) and Douglas Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession (1954). American-born Kruger was a descendant of Transvaal’s (current South Africa) 19th century king Paul Krüger. Making his Broadway debut in 1915, Kruger quickly became a matinée idol, a reputation he carried with him into silent film in the 20s. However, with sound, he soon found his niche playing charming villains both in film and TV. While the titles listed above prove that Kruger was indeed an in-demand and respected character actor, he was never among Hollywood’s a-list tier – as demonstrated by his appearances in B-horrors like Dracula’s Daughter (1936), Woman Who Came Back (1945), and as an Ersatz Karloff in Universal’s third “Ape Woman” instalment The Jungle Captive (1945, review) and Paramount’s The Colossus of New York (1958).

Ross Martin plays the unlucky genius who gets hit by a truck and becomes the titular menace of The Colossus of New York. Ross’ charm strikes a chord in the few scenes he has in the beginning of the film, before he gets assigned to voice work, as Ed Wolff takes over duties inside the suit. This charm served him well in Hollywood, especially in the sci-fi/western TV show The Wild Wild West, in which he played one of the leads, the inventor spy Artemus Gordon, between 1965 and 1969.

Born Martin Rosenblatt in Poland in 1920, Martin grew up in New York, studied business and law and trained as a concert violinist before embarking on an acting career in radio, TV and stage. George Pal’s wobbly space epic Conquest of Space (1955, review) was his first movie role, and he quickly gained fame for his ability to play diverse roles, and was considered a master of accents. He spent the majority of his career in TV, and his movie credits are primarily for minor roles.

Robert Hutton is in The Colossus of New York in a wholly superfluous role, set up as the “second love interest”, or in this case “third love interest”, familiar from the horror films of the 30s, when the romantic lead turns out to be a monster or mad scientist who dies in the end. Hutton carried some minor marquee draw – his likeness to James Stewart awarded him a seven-year contract with Warner Brothers in the early 40s when Stewart himself was one of the many stars drafted for the entertainment division of the US armed forces in WWII. In so-called “victory casting”, Hutton was put in the lead in a number of B-movies i Jimmy Stewart-type roles.

When his contract with Warner ran out in the early 50s, Hutton struggled to find decent roles, but kept busy in TV shows and B-movies. Hutton is well-known to fans of science fiction because of his leads in The Man Without a Body (1957, review), Invisible Invaders (1959), The Slime People (1963), The Vulture (1966) and They Came from Beyond Space (1967). He also appeared in The Colossus of New York (1958) and Trog (1970).

Dr. Spensser’s son in The Colossus of New York is played by the oft-used, oft-annoying child actor Charles Herbert, who graced the screen in 20 films between 1954 and 1960, and appeared in over 50 TV shows in during his 14-year career. Discoverd by an agent on a bus at the age of 5, Herbert quickly became a favourite with producers and directors because of his cute features and his precocious acting style. Few of his efforts are watchable today, because of his tendency to play children as if they were trying to be adults, combined with the 50s prevalence with child actors to shout all their lines from the top of their lungs. Herbert was featured in a number of high-profile films, but is best remembered today for his appearances in genre fare, such as The Monster that Challenged the World (1957, review), The Fly (1958, review), The Colossus of New York (1958), 13 Ghosts (1960) and The Boy and the Pirates (1960).

As Herbert began to grow into adolescence, and perhaps because of changing styles in acting, his movie opportunities came to an abrupt halt after 1960. However, he kept busy in TV, in particular in the daytime soap opera The Clear Horizon (1960–1962) – slightly interesting for this page, since it takes place at Cape Canaveral and follows an astronaut played by Ed Kemmer (another SF staple), his co-workers and family. Herbert played Kemmer’s son. His last TV appearance came in 1966.

After he turned 21 in 1969, Herbert’s life turned into a tragic affair. Like many child stars, Herbert found out when reaching adulthood that none of the money he had made during his stardom had been put away for him. According to an interview with Tom Weaver, Herbert’s father was chronically ill and had to be taken care of by his mother, so neither of the parents were working. Herbert had supported his family since the age of 5, and studios at the time had no obligation to any of the money made by child actors, and paid it all to their legal guardians. This meant all his earnings went directly to keeping bread on the family table. He wasn’t able to turn his child acting career into an adult acting career – as he explains to Tom Weaver, he just didn’t realise that in order to do adult roles, you actually had to learn the craft of acting, and when studios and agents wanted to put him in acting school, he flipped them off. But having had a patchy education in primary school at best, and no vocational education, he found himself floundering, and turned to drugs, which he was addicted to for most of his adult life. He straightened himself out in 2004, and spent much of his remaining life campaigning for the rights of child actors. He passed away in 2015.

Herbert has few friends among modern critics, and I was not particularly kind to him in my review of The Fly either. I feel a bit bad for talking down his performance after learning of his tragic fate, but the truth is that for a 21st century viewer, the style popular among so many child actors in the 50s – a sort of loud, precocious charicature of what kids are like in real life, is extremely irritating and constantly threatens to pull the viewer out of the movie.

A mention should also go to Ed Wolff, the towering 7,4 or over 220 cm tall actor who plays the titular Colossus. Wolff arrived in Hollywood in 1925 from Trinidad and Tobago, figuring Hollywood might have use for a tall man. His first role was as the mob leader at the end of Universal’s classic The Phantom of the Opera (1925), and he did a handful of roles, almost always uncredited, during the 30s and 40s. The only credited movie role in his career was as the robot in the Bela Lugosi serial The Phantom Creeps (1939). Another science fiction role came along with Invaders from Mars (1953, review), in which he played one of the fuzzy green aliens. As stated, he played the titular monster in The Colossus of New York (1958), and the next year starred as yet another titular menace in The Return of the Fly (1959).

Apparently, Wolff’s height wasn’t a result of a syndrome or illness, as was sometimes the case with tall Hollywood actors – he came from a family of tall people. When younger he worked as a circus giant, but later became a house painter in Hollywood – always eager to put the brush aside when someone needed a monster or a giant for a movie. IMDb gives him 10 movie credits. Unfortunately the only photo of Wolff I have found is peddled by Shutterstock for 130€, so I won’t be using that one, but you can google it if you like.

Also look out for bit-part staples like Roy Engel and Harold Miller, who have graced many of our reviews here at Scifist.

An interesting lady is the screenwriter of The Colossus of New York, Thelma Schnee, married Moss. Although she graduated from Carnegie Tech, she had her eyes set on a career as an actor, and spent much of the 40s and early 50s on stage, on and off Broadway, both as an actor and as a playwright. In the 50s she had a stint in Hollywood. Her acting credits amounted to a handful of roles in TV shows, but she had slightly better luck as a screenwriter, making a few waves for her screenplay of the Alec Guinness classic Father Brown (1954). She wrote two episodes of Science Fiction Theatre (1955-1956) and penned the script for Paramount’s low-budget sci-fi film The Colussus of New York (1958).

However, Moss soon left showbiz behind and re-entered academia, at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute. Her own struggle with mental health, two failed suicide attempts and an apparently successful round of LSD treatment fuelled her interest in psychology and the workings of the brain. Moreover, her interest would turn toward fringe science, as she became head of the short-lived parapsychology department at UCLA, researching topics like levitation, ghosts, hypnosis, alternative medicine and Kirlian photography (electron photography), which she claimed could capture a person’s aura. Moss made several research trips to the Soviet Union, where Kirlian photography had originated and wrote two books on the subject. Like most paranormal claims, Kirlian photography’s supposed connection with so-called auras have been largely debunked.

Composers (Nathan) Van Cleave and Fred Steiner were both prolific and in-demand both for film and TV, not seldom working together, often because of time restraints. Van Cleave was Steiner’s mentor, and Steiner often orchestrated Van Cleave’s compositions. At the time of the making of The Colossus of New York, Van Cleave was on contract with Paramount, scoring a number of low-budget films. As mentioned above, the score is unusual inasmuch as it is created only with three pianos. Since Fred Steiner was a more accomplished pianist, Van Cleave asked him to contribute his own pieces to the score. Neither composer was ever considered the A-list of Hollywood, and did their most memorable work for television. Steiner is best known for composing the theme music for Perry Mason (1957–1966) and was part of a large group of composers nominated för an Oscar for The Colour Purple (1985). However, science fiction is hugely indebted to both men.

Van Cleave’s music can mostly be heard in SF movies: he composed the score for Conquest of Space (1955), The Space Children (1958, review), The Colossus of New York, Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964) and Project X (1968). He also wrote the title theme for I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958, review). Both Van Cleave and Steiner were heavily involved in the creation of the music for the groundbreaking TV show The Twilight Zone (1959–1964), and their music can be heard in dozens upon dozens of episodes. Steiner is mostly revered by SF fans for his work for the TV show Star Trek (1966–1969) – he scored 29 of the show’s 79 episodes. His work was “richly orchestral, often with dark, heavy textures in brass and low strings”, set much of the tone of the series’ musical style. He continued to contribute to several Star Trek shows and movies over the years, and also provided additional music to Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983). His music can also be heard in films like The Colossus of New York (1958), Teenagers from Outer Space (1959) Kingdom of the Spiders (1977) and the TV show Lost in Space (1966-1967).

Of course, makeup and special effects designers Charles Gemora and John P. Fulton also deserve mention. Read more on them by clicking the links.

Janne Wass

The Colossus of New York. 1958, USA. Directed by Eugene Lourié. Written by Thelma Schnee, Willis Goldbeck. Starring: John Baragrey, Mala Powers, Otto Kruger, Robert Hutton, Ross Martin, Charles Herbert, Ed Wolff. Music: Van Cleave, Fred Steiner. Cinematography: John Warren. Editing: Floyd Knudtson. Art direction: John Goodman, Hal Pereira. Makeup: Wally Westmore. Special effects: Farciot Edouart, John P. Fulton. Colossus designer: Charles Gemora, Ralph Jester. Produced by William Alland for Paramount.

Leave a comment