A radioactive dinosaur stomps London in this British-American 1959 co-production. Writer/director Eugène Lourié all but presents a carbon copy of his previous hit The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion work is rushed and sloppy. It’s not terrible, but by the numbers. 4/10

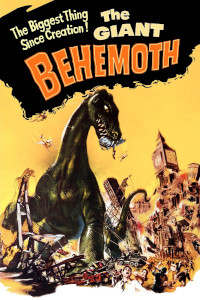

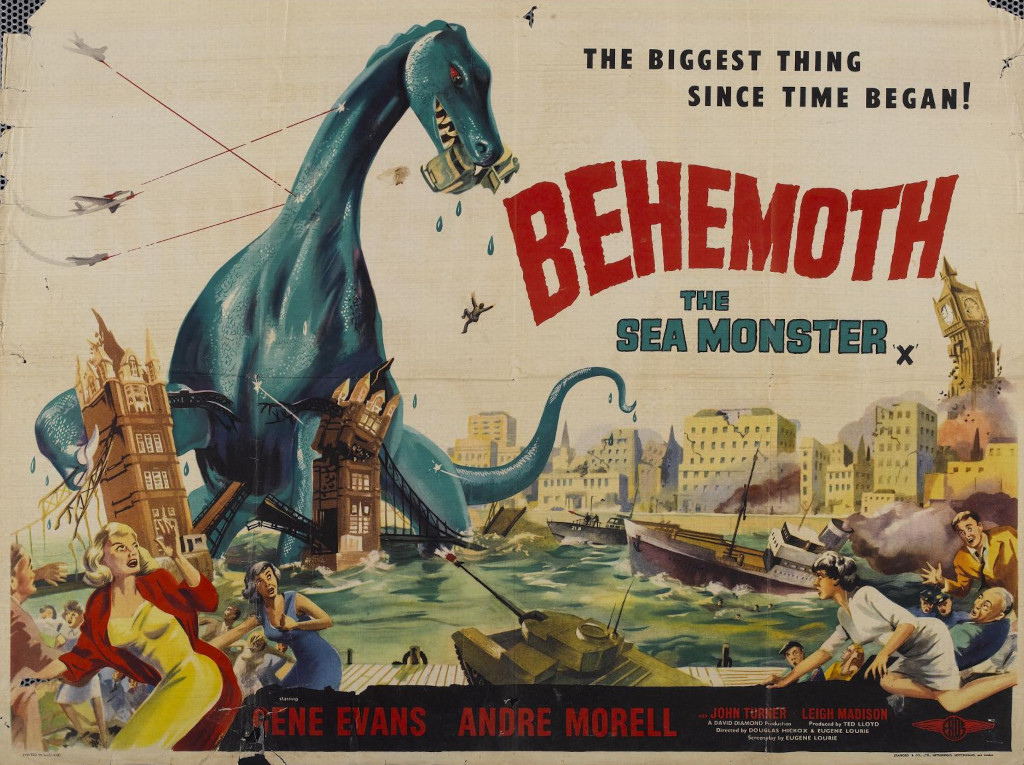

Behemoth the Sea Monster. 1959, US/UK. Directed by Eugène Lourié. Written by Daniel James, Eugène Lourié, Robert Abel, Allen Adler. Starring: Gene Evans, André Morell, John Turner, Leigh Madison. Produced by David Diamond. IMDb: 5.7/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 17/100. Metacritic: N/A.

As American marine biologist Steve Kramer (Gene Evans) hold a lecture in London about the threat to marine life from nuclear testing, reports come in from Cornwall of strange goings-on. A Cornish fisherman has died from radiation burns, whispering with his dying breath: “Behemoth!”, and the beaches have been littered by dead fish washed up from the sea. Kramer teams up with Prof. Bickford (André Morell) from the British atomic agency and they set out to investigate.

So begins the US/UK co-production Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959), released in the US as The Giant Behemoth, directed by Eugène Lourié, with stop-motion effects from legendary Willis O’Brien and Pete Peterson. Filmed in London, it was O’Brien’s last movie. Heavily re-written at the request of the producer, it is essentially a re-tread of Lourié’s 1953 classic The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (review).

After interviewing the dead fisherman’s daughter Jean (Leigh Madison) and her boyfriend (John Turner), who has caught radiation burns from a strange blob on the beach, the two scientists head back to London to analyse the dead fish, which they find to be radioactive. Meanwhile some radioactive creature attacks a farm in Essex, leaving behind a footprint larger than a car. Kramer and Bickford then add eccentric paleontologist Dr. Sampson (John MacGowran) to their team, and he identifies the print as that of an extinct aquatic dinosaur, a paleosaurus, that has somehow survived through millions of years in the deep of the ocean. Sampson explains that the paleosaurus emits electric pulses, much like an electric eel. Kramer concludes that the reptile has been turned radioactive through nuclear testing, and that its radioactivity is piggybacking on its electrical pulses, which is how it is able to kill by radiation. He also theorises that the radioactivity is slowly killing the creature, and because its species always returns to its place of birth to die, it is going to try to swim up the Thames river straight to London, leaving a trail of havoc in its wake. This, the three conclude, must be prevented.

Spotting the beast turns out to be difficult, as it somehow, unexplainedly, does not register on radar. Dr. Sampson goes up in a helicopter to try to spot it from the air, but one of the radioactive pulses blows up the chopper. The Behemoth then closes in on London and sinks a car ferry. Authorities evacuate the area around the mouth of the Thames. With its streets deserted and army spotters stationed around the city, the city holds its breath in terror. Until all hell breaks loose, and the Behemoth turns up to Stomp London, pulling down power lines, causing petrol tanks to explode, turning houses into rubble and sending panicked citicens fleeing in the streets.

While disaster rages on the streets, Bickford and Kramer rush to complete their secret weapon. Having determined that they can’t bomb the beast from the air, as it would send radioactive dinosaur limbs flying all over London, they have decided to arm a torpedo with radium and fire it at the monster from a submarine. If they can penetrate the Behemoth’s flesh without blowing it up, the increased radiation from the radium will cause it to “burn itself out from the inside”, by speeding up the deterioration that is already caused by its currently radioactive state. While the army drives the Behemoth toward the river, Kramer enters a mini submarine with its commander (Maurice Kauffmann) and take up the hunt for the Giant Behemoth…

Background & Analysis

The story of Behemoth the Sea Monster seems to start with Warner’s 1957 sci-fi monster movie The Black Scorpion (review). Eugène Lourié was set to the direct the movie, but apparently had a falling-out with one of the film’s backers and was removed from the production. This, according to film historian Bill Warren, led to Lourié being approached by independent producer David Diamond with an offer to direct Behemoth the Sea Monster in London, as a co-production with British Eros Film/Artistes Alliance.

According to Tom Weaver’s interview with Lourié, the movie was originally supposed to be quite different: instead of a dinosaur, the menace was supposed to be some sort of radioactive blob moving in the water. The original screenplay was done by American writers Robert Abel and Allen Adler. However, when Eros Film learned that Lourié was involved they demanded that the monster be changed to a dinosaur, and that the script be changed to more closely resemble The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Lourié brought in his blacklisted friend Daniel James, who had also contributed to Beast, and together they made the appropriate rewrites. In the Weaver interview, Lourié says that he originally only intended to use this script to appease Eros Film, and had planned major alterations to the shooting script, making it feel less like a carbon copy of Beast. However, he and James never got around to doing the rewrites, so the “sell-in” script was filmed almost as such.Lourié tells Weaver: “I did resent this, but not too much. Visually, it is much easier to see the villain-beast than to see radiation”.

It was Ray Harryhausen’s incredible stop-motion and miniature work that had made The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms such a success. One imagines that Lourié approached Harryhausen for Behemoth, but that he was either busy with other projects or too expensive. The call then went out to Harryhausen’s mentor, Willis O’Brien, the man behind King Kong (1933, review). Lourié tells Weaver that he wanted to outsource all the special effects to O’Brien and Pete Peterson, but that the producers decided to make Jack Rabin and Irving Block responsible for the effects. Not a bad call per se, as the the two were very adept effects creators, who were used to working magic with meagre resources. But O’Brien’s and Peterson’s budget for the stop-motion work then had to be extracted from the total special effects budget of $20,000. This meant Obie and Peterson only had eight weeks to create all the effects for the movie, and were forced to take a few shortcuts. (Sidenote: Wikipedia claims the budget for the film was $750,000. This was certainly not the case. The information comes from a Variety PR plug, in which Diamond probably inflated the budget in order to drum up interest in the film. I’m calling it at $150,000, tops.)

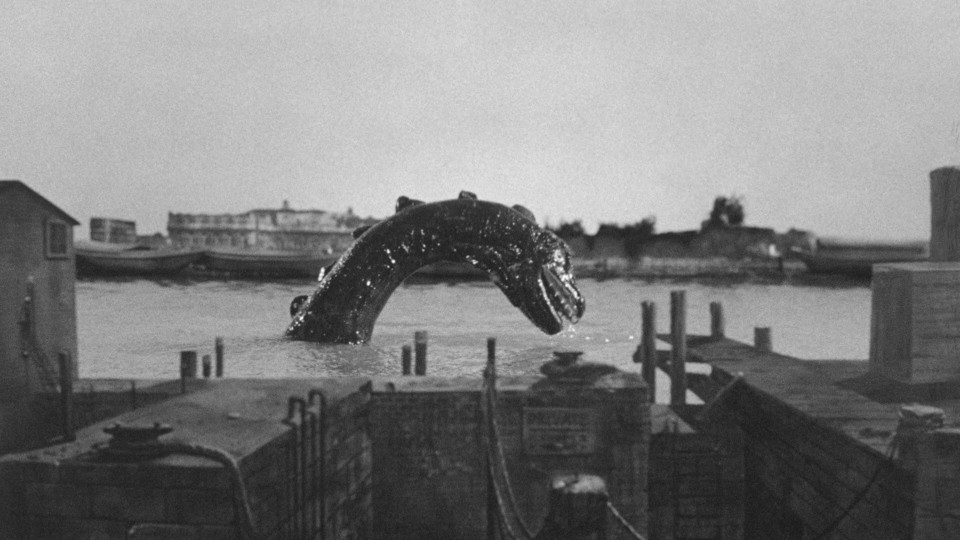

Instead of going full stop-motion, the duo decided to create the effects of the Behemoth in the water with a hand puppet. In the film, the puppet monster comes across as a bit of a letdown because of its immobile head and jaw. Originally the head was controllable, but according to one story, Irving Block played a bit to forcefully with the controls and broke them.

The short shooting schedule and low budget also meant that O’Brien and Peterson had to cut corners with the stop-motion animation. The problems begin with the puppet itself, on which the seams between the different rubber parts that went over the armature are clearly visible. As a puppet, it is a more anatomically correct dinosaur than the monster than the one in Beast, but it is also less expressive. The animation is unusually jerky for O’Brien and Peterson, a sign that they had to hurry the production. Other signs of a rushed production is that the shots in which the entire animal is on screen are rare. Much of the footage is simply of the Behemoth’s head, or the lower half of the dino – saving the animators precious time. People are very rarely in the same shot as the monster, and some shots, such as the Behemoth stomping a car, are reused not only two but sometimes three times. In short, this is not the quality we are used to from Willis O’Brien, and in a movie in which the stop-motion monster is supposed to be the main draw, this is a major problem.

That said, it is a problem that could be overcome with a good script and an interesting story. But here the film falters as well. Not only are the happenings on screen all too familiar from The Beast of 20,000 Fathoms, its also a very inferior copy of the original movie. The main problem is that the characters have no personality, and consequently the film has no emotional anchor. Gene Evans was a good actor, and in many ways worked as said anchor in Donovan’s Brain (1953, review). However, as Steve Karnes, nominally the lead in Behemoth, he is only used for plot advancement and exposition, as are virtually all other characters as well. André Morell’s Prof. Bickford is in the movie only to give Karnes someone to talk to. Jack MacGowran‘s paleontologist is Behemoth’s version of Cecil Kellaway’s sympathetic and eccentric egghead from Beast. But his character is introduced too late and has too little screentime in order to give his death the same emotional punch as Kellaway’s Dr. Elson’s. Elson was one of the main characters in the film, and very much loved by his assistant Lee, who was the leading lady of Beast. Elson’s heroic sacrifice is the most heart-wrenching moment of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. When MacGowran’s Dr. Sampson dies, we only mourn that his death elimimates the only interesting character in the Behemoth the Sea Monster.

Behemoth the Sea Monster also lingers too long on characters that disappear from the movie entirely once the monster hunt gets going. As the movie starts in Cornwall, we spend a good 20 of the film’s 80-minute running time there, getting to know the dead fisherman’s daughter Jean (Leigh Madison) and her boyfriend John (John Turner), expecting them to be central characters. Jean is the only character in the movie with any personal stake in the proceedings, and she would have been the obvious emotional anchor that the picture needed. But both Jean, John and all of Cornwall are discarded at the 25-minute mark, never to be mentioned again. The same problem applies to the above mentioned Dr. Sampson, who is on screen no longer than 10 minutes before his helicopter is blown up.

As a monster chase movie, Behemoth the Sea Monster is functional. It builds up its beats neatly, from the mystery intro in Cornwall to the middle section where the geeks of the cast figure out what they are dealing with, to the finale, where the monster appears in all its glory and wreaks havoc. All the parts are there, but they feel as if played by the numbers, which is understandable, as the script the movie is based on was simply a placeholder that was never re-written.

Had Louríe had more time to polish, he probably would have avoided a number of oddities arising from the fact that the monster in the original script was decidedly different. The original menace was a gelatinous, radioactive mass moving through the waters undetected. That would explain the radioactive blob that turns up on the shore in Cornwall in the beginning of the movie, but in the finished film it is never explained how the pulsating blob is connected to the dinosaur, and no more blobs are ever mentioned. A key element in the film is that the monster can’t be spotted by radar, which is, for example, the reason that Dr. Sampson goes out to spot it in a helicopter and gets himself killed. Again, this is logical if we are dealing with a gelatinous mass that can dissolve in water, but less logical for a 100-foot dinosaur. No explanation is given to the odd fact that the Behemoth can avoid radar, it is simply stated as a truth.

Other questions also go unanswered. Where on Earth did the dino appear from in the first place? Both The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Gojira (1954, review) provided (fantastic, but nonetheless) answers to the origins of their monsters and why they suddenly appeared. But Behemoth just appears out of nowhere, without an explanation. Furthermore, if we are to buy the plot contrivance that the Behemoth swims to its birthplace up the Thames to die (as it has for millions of years, according to Karnes), why has no-one seen its ancestors swimming up or down the Thames before, wreaking similar havoc? This single specimen can hardly be millions of years old, which means someone ought to have noticed a GIANT BLOODY MONSTER swimming up the Thames during the past 9000 years of settlement around the river.

This is a film in which the protagonist is an expert in everything – from dinosaurs to nuclear warheads. He makes astounding leaps of logic that all miraculously turn out to be true. It feels as if Karnes reaches his conclusions because the plot requires him to do so, rather than through any train of logic.

Behemoth the Sea Monster came in at the tail end of the nuclear monster fad. As I have written before, this was a time when the symbolism of the early movies in the subgenre had devolved into stale tropes. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Gojira gave their monsters symbolic weight and an emotional grounding. By the time Behemoth came along, the ideas originally embedded in the creatures had vanished and left the creatures as dumb, hollow monsters. Screenwriters were no longer telling stories, but rather creating vehicles for the low-budget monsters of the day. Studios knew that radioactive dinosaurs drew crowds at the drive-in regardless of the overall quality of the film.

Acting-wise the film is as good as its script allows. As stated, Gene Evans was a good actor, but his character in Behemoth the Sea Monster is so one-dimensional that it’s impossible to do anything with it. The same can be said for André Morell. A good actor, Morell does everything right in this picture, but he is wasted in a role designed for Evans to throw exposition at. Jack MacGowran, a celebrated stage actor known for his work with Samuel Beckett, is a fun distraction as the kindly, enthusiastic paleontologist, but, as stated, his appearence is way too brief. The rest of the movie is filled with capable British character actors, with Leigh Madison and John Turner making the most of their brief turns in the picture.

Edwin Astley’s orchestral score is suitably dramatic, but has an annoying tendency to hit the audience with stingers each and every time something even halfway dramatic is revealed. The score works well as an atmosphere builder, though.

I would have loved to see the original script, as it sounds quite original. The movie starts out well, and had it remained in Cornwall, fighting some unknown radiation blob from the sea, this might have turned into a really taut, claustrophobic SF thriller. A blobbish monster would have been possible for the effects creators do realise really well on the limited budget they had. Alas, this is a film we will never see. Behemoth the Sea Monster is not terrible. Eugène Louríe had a good eye for visuals, and there’s a number of striking shots when the stop-motion isn’t involved. The best part of the movie is when London is gearing up for the monster to strike, with scenes of the army evacuating houses, and eerie, atmospheric shots of empty streets, awaiting the onslaught. It’s a film that’s perfectly fine for a Saturday matinee if you’re in the mood for a silly monster movie. But it is a soulless film that no-one was particularly interested in doing, and one that simply ticks of one box after the other as a blueprint for a certain subgenre. The characters are only plot enablers, and not even the good cast can do anything with them. It’s a lesser retread of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. At least the ending is different, as the heroes take to a submarine to battle the monster in the end. But not even that is original – it was lifted from the Ray Harryhausen film It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955, review).

Reception & Legacy

Behemoth the Sea Monster premiered in the US in March, 1959, and in the uk in October, 1959. In the US it was booked as a double bill with the now forgotten crime/romance film Arson for Hire starring Steve Brodie. It was distributed by Allied Artists in the US. AA renamed the movie The Giant Behemoth in a typically blockheaded American fashion, so that the title came to mean “The Giant Giant”. I have found no box office numbers for the movie, but as it was made on such a minuscule budget, it probably made a decent little profit.

The Giant Behemoth received positive reviews in the American trade press. Many outlets noted that the idea itself was well-worn, but praised the movie for its well-structured script and its special effects. Variety called the film “effective” and commended director Louríe for “piling one chill on another”, as well as for the story which “is believable enough, moving quickly and never getting out of hand. On the acting side, the magazine had some special sexist praise for Leigh Madison, who “proves entirely capable of acting as well as attracting”.

Harrison’s Reports called it an “above-average program picture of its kind”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor called it “very well done” and said it had “a goodly amount of suspense, excellent special effects, an interesting yarn that holds up well from start to finish, good acting and commendable direction and production”. Several US trade papers also mentioned the British locations as refreshingly novel. British Monthly Film Bulletin was not quite as positive, giving the movie its “Average” rating: “This is considerably better than many recent essays in monster science-fiction, both in its suspense and staging; but the story, though put over as convincingly as possible, remains stuck at routine outsize-palaeontology level.”

In his book Science Fiction in the Cinema (1970), John Baxter talks about the attempts by British filmmakers to ape the American scince fiction movies in low-budget production in the late 50s, and says that Behemoth the Sea Monster was the only movie that brought something interesting to the table, in particular the scene with the examination of the glowing, irradiated fish. This is also the one scene mentioned in Phil Hardy’s The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies (1984). Hardy notes that “the picture [is] routine, at best” In his review for White Wolf magazine in 1992, James Lowder gave the film 2/5 stars, writing: “Behemoth’s performances are workmanlike, but hardly inspired. The special effects are also lackluster. Master monster-maker Willis O’Brien ended his career with this dreary film. A few sequences display his touch […] but the film’s effects fall far short of his brilliant work on King Kong or The Lost World.” In his book Keep Watching the Skies! (2009) Bill Warren calls the movie “a perfunctory monster-on-the-loose film of little distinction”.

Many modern critics have pointed out the fact that the UK hasn’t produced a lot of high-quality giant monster movies. Or as Chris Wood puts it at British Horror Movies: “Behemoth The Sea Monster is, like every other British made monster movie, absolutely rubbish”. Richard Scheib at Moria Review is slightly more diplomatic, giving the picture 2/5 stars: “[Lourié] is reasonably effective at drawing British stiff upper-lip figures and provincial types. The film though fails to work. The characters are one-dimensional. Almost none of them emerge to the forefront of the story as distinct heroes – they are all indistinct plot functionaries. […] Lourie’s direction is mostly pedestrian. Sometimes he is capable of delivering scenes that offer effective mood […] However, few of the scenes stand out here, apart from one with the scientists examining a fish whose radioactivity only becomes apparent when the lights are turned out and it is found glowing in the dark.”

Kris Davies at Quota Quickie writes: “The earlier part of the film works better to be honest as you don’t actually see the monster, after the unveil of the beast later on it does descend into a bit of a model building destroying romp. The monster scenes are pretty well done though. […] The main problem with the film is the British-ness of it all. I’m not sure stiff-upper-lip characters work that well when the enemy is a giant sea monster and not the Luftwaffe.”

Several critics, including the always snarky Andrew “zero stars” Wickliffe at The Stop Button, mistake Behemoth the Sea Monster for a Gojira ripoff, when it was in fact a ripoff of the film that Gojira ripped off, made by the same guy that made the original film. In his – what else? – zero-star review or Behemoth, Wickliffe writes: “Behemoth might be unique in the giant monster genre in that respect–it’s more interesting before the giant monster shows up. Once the monster shows up, the film slows down to a crawl–the last ten minutes are grueling. Before, during the investigation, Behemoth at least entertains and the director, Eugène Lourié, has some good composition in the British seaside town and particularly during exposition scenes.”

Cast & Crew

French writer/director Eugène Lourié primarily worked as a production designer, first in France, and from the 40s onward in Hollywood, where he immigrated after the outbreak of WWII. In France he was considered one of the country’s top production designers, and worked for directors like Max Ophüls, Marcel L’Herbier and Jean Renoir, for whom he designed the classics La grande illusion (1937) and La règle du jeu (1939). In the US, he continued his collaboration with Renoir, for whom he designed four American movies between 1943 and 1951. In 1951 he also worked as production designer on Charles Chaplin’s last film, Limelight.

However, for the science fiction genre, Lourié is primarily interesting as a director. His directorial debut was a low-to-mid-budget monster movie inspired by the massive success of the 1952 theatrical re-release of King Kong (1933, review) into theatres: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review). While dramatically not much above average, hampered by a thin and illogical script, the movie’s spectacular effects by Ray Harryhausen made it an enormous success both in the US and internationally. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms became the blueprint for the giant monster movie (replicated by William Alland on numerous occasions) and directly inspired Japanese studio Toho to produce Gojira (1954, review). The Colossus of New York (1958) was only Lourié’s second feature film as a director, although he did some work for TV. For his two final films as director, Lourié ended up – partly against his own wishes – recreating his magnum opus. He made Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959) and Gorgo (1961) in Britain. Despite the fact that the films were both going to be somewhat different different, both ended up featuring a dinosaur-esque sea monster destroying London, because of pressure from producers. However, Gorgo, featuring a mother monster trying to save a baby monster from captivity, is generally considered one of the better efforts in the subgenre. After failing to break out of the shadow of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms as a director, Lourié decided to focus on his work as a production and art designer, which he did until the late 70s.

Gene Evans was a noted character actor, racking up large supporting roles in westerns and even leading man roles in war films like Fixed Bayonets and The Steel Helmet (both 1951). The latter, directed by Samuel Fuller, is the role that he is best remembered for. He had a key role in Blake Edward’s Operation Petticoat (1959) and another starring role in Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963). The stocky, red-headed actor played second lead along with Lew Ayres and Nancy Reagan in the SF movie Donovan’s Brain (1953, review) and played lead in Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959). He had a small role in the 1989 low-budget film Split, and was also one of the leads in the 1974 cult horror movie Peopletoys. Evans was awarded with a Golden Boot in 1988 for his work in westerns.

André Morell, playing Gene Evans’ British sidekick, was a distinguished character actor of the stage and the screen, who appeared in A-class movies such as Ben-Hur and The Bridge on the River Kwai. However, to friends of science fiction, he is best known for having played Bernard Quatermass in the third season of BBC’s Quatermass franchise, Quatermass and the Pit (1958). In fact, he was the first pick for the original series, The Quatermass Experiment (1953, review), but turned it down. When Reginald Tate, who got the role, passed away shortly before the filming of the second season in 1955, Morell was once again approached, but again declined. And when Hammer made the movie version of Quatermass and the Pit, they asked Morell to reprise the role, but he declined for the third time. Morell also played one of the leads in Eugène Lourié’s Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959), played Kassim in The Vengeance of She (1968) and appeared in three episodes of Doctor Who in 1966. Friends of fantasy may be interested to know that he voiced Elrond in Ralph Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings animation in 1978. He played Dr. Watson opposite Peter Cushing’s Sherlock Holmes and Christopher Lee’s Henry Baskerville in Terence Fisher’s classic adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1959. He then played the lead in three more of Hammer’s horror movies: The Shadow of the Cat (1961), The Plague of the Zombies (1966) and The Mummy’s Shroud (1967). Morell passed away in 1978 from lung cancer.

It could be easy to dismiss Jack MacGowran, who turns up very briefly as the funny paleontologist in Behemoth the Sea Monster, as simply a comic sidekick. In fact, MacGowran was one of the most lauded stage actors of Ireland, famous for being one of the most foremost interpreters of Samuel Beckett and Séan O’Casey. So much so, thatBeckett even wrote a play specifically for him. But MacGowran was also a sought-after character actor for film and TV. He appeared in close to 40 movies and as many TV shows between 1951 and 1974. Genre fans may know him best for his rare lead in Roman Polanski’s horror comedy The Fearless Vampire Killers/Dance of the Vampire (1967), or for his role as Burke Dennings inThe Exorcist (1973). He also appeared in Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959) andThe Brain (1962).

The rest of the cast is made up of reliable British character actors. There’s Tom Chatto, whom we’ve seen as Prof. Quatermass’ partner in Quatermass 2 (1957, review), James Dyrenforth, who played the mayor in Fiend Without a Face (1958, review) and Bill Edwards who had the co-lead as the maverick pilot turned into a monster in First Man Into Space (1959, review). André Maranne will be forever remebered as Herbert Lom’s hapless assistant François Chevalier and Derren Nesbitt had a good career run playing shifty characters, most famously asClint Eastwood’s Gestapo foil in Where Eagles Dare (1968). Stuntman and background actor Arthur Howell appeared in a good number of science fiction movies, including Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), where he played a stormtrooper.

Irving Block and Jack Rabin are unsung heroes of low-budget SF, often working with Louis DeWitt on special effects, writing and producing. Rabin and Block had started their sci-fi collaboration on Rocketship X-M, with Neumann and Struss, and continued on Flight to Mars (1951, review), and would go on to become B movie legends in the fifties. They went on to collaborate on Unknown World (1953, review), Invaders from Mars, World Without End (1954, review), Monster from Green Hell (review), The Invisible Boy, Kronos (both 1957), War of the Satellites (1958, review), The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959) and Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959). Both also worked on a number of other sci-fi films separately. Rabin worked on movies including The Man from Planet X, Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), Robot Monster (1953, review), Deathsport (1978) and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Block did work on films like Captive Women (1952, review), Forbidden Planet (1956, review) and The Atomic Submarine (1959).

Composer Edwin Astley carved out a successful career creating themes and soundtracks for British films and TV shows. He is best known for creating the theme song for the classic TV series The Saint (1962-1969) starring Roger Moore before he became James Bond. He was also the father-in-law to The Who’s Pete Townshend. He is not, however, related to Rick Astley.

Janne Wass

Behemoth the Sea Monster. 1959, US/UK. Directed by Eugène Lourié. Written by Daniel James, Eugène Lourié, Robert Abel, Allen Adler. Starring: Gene Evans, André Morell, John Turner, Leigh Madison, Jack MacGowran, Maurice Kaufmann, Henri Vidon, Leonard Sachs. Music: Edwin Astley. Cinematography: Ken Hodges. Creature effects: Willis O’Brien, Pete Peterson. Special effects: Jack Rabin, Irving Block. Art direction: Harry White. Makeup: Jimmy Evans. Produced by David Diamond for David Diamond Productions, Eros Film/Artistes Alliance & Allied Artists.

Leave a comment