A ruthless scientist creates a teenage monster in his basement and tries to hide it from his fiancée. Herman Cohen’s 1957 follow-up to the smash hit I Was a Teenage Werewolf is a slow-moving affair saved by a toungue-in-cheek script. 4/10

I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. Directed by Herbert Strock. Written by Aben Kandel & Herman Cohen. Starring: Whit Bissell, Phyllis Coates, Cary Conway, Robert Burton. Procuced by Herman Cohen. IMDb: 5.1/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 4.5/10. Metacritic: N/A.

Mad scientist Professor Frankenstein (Whit Bissell) is the descendant of you-know-who, who plans to perfect his forefather’s dream to you-know-what from his laboratory in an all-American smalltown. But unlike old Victor Frankenstein, he means to use body parts from dead teenagers, as they are more “alive”. Barely has he finished this sentence in conversation with his friend and and reluctant assistant Dr. Karlton (Robert Burton), before a carful of teenagers happen to crash just outside his front door, and one of the bodies is conveniently flung out of sight, where and Karlton simply pick it up and carry it into Frankenstein’s basement laboratory.

Released the same year as Hammer’s groundbreaking adaptation The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review), I Was a Teenage Frankenstein was American International Pictures’ follow-up to their barnstormer I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review), released earlier the same year. Both films were produced by Herman Cohen and co-written by Cohen and Aben Kandel. Gene Fowler directed the first, while workhorse Herbert Strock was director on the second. Like Teenage Werewolf, Teenage Frankenstein has also become a cult classic.

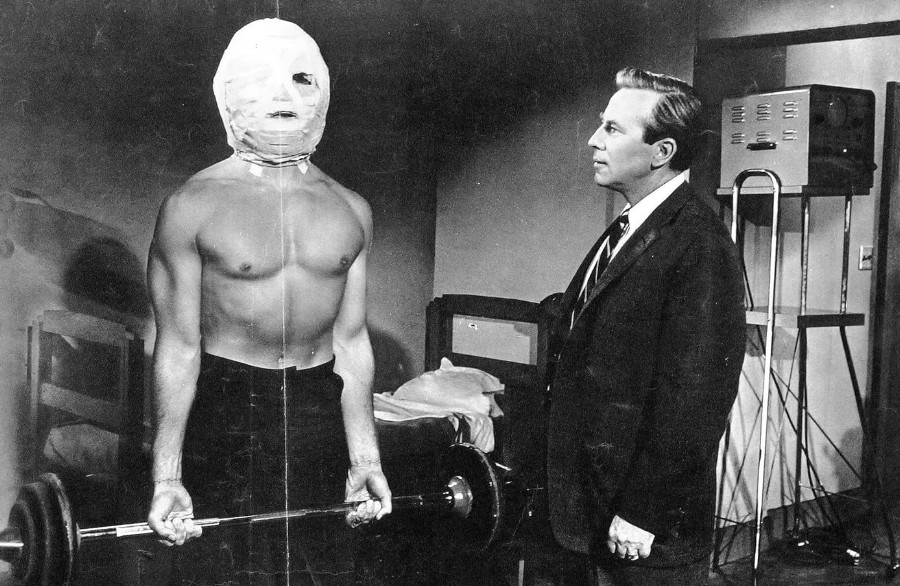

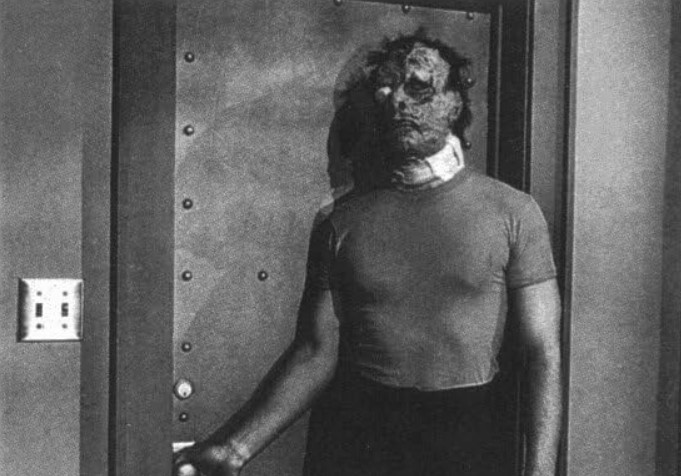

The teenage creature (Gary Conway) is assembled from the body of the dead car crash victim and some bits and bolts Prof. Frankenstein has collected from a plane crash. After a few busy days of work in the lab – work that is kept secret from Frankenstein’s fiancée Margaret (Phyllis Coates) – the teenage menace is ready. Ready, with the exception of the face, which is still covered by bandages. When the creature wakes up, Frankenstein starts to sternly condition and educate him, so that he will be presentable to the scientific elite. But the creature, while wellbehaving, is a teenager who doesn’t like to be locked up in his room. When pressed on why he keeps him hidden in the basement, Frankenstein removes the bandages and gives the creature a mirror – revealing a horrible mess of a face, badly burnt and scarred by the car crash, with one giant eye morbidly bulging from its socket. Frankenstein promises that in time, the creature will get a new face – just have patience.

Meanwhile, the day of Frankenstein’s and Margaret’s wedding is drawing near, but Frankenstein treats it as a trivial matter, an inconvience, and keeps treating Margaret terribly. When Frank refuses to tell her what he is up to in the basement, she secretly replicates his key and sneaks in on the unwitting monster, who gets as much a fright as she does, before she runs out and slams the door behind her.

Later, the creature grows tired of sitting around, breaks out of the lab and takes a nightly stroll, during which he does a peeping Tom number of a voluptuous young blonde in her nightgown (Angela Austin). When she sees him in the window, she screams, and the creature breaks in and tries to silence her, accidentally killing her in the process. Escaping, he is seen by multiple witnesses, and returns home, where he is given a scalding. Police later come by asking questions, but Frankenstein convinces them that the witnesses were in shock and saw what they wanted to see.

Finally the day comes when the creature is to receive a new face. Frank takes him out to lovers’ lane, where he kills and kidnaps a young man (also Gary Conway) who is necking a girl in a car (Joy Stoner). The girl describes to the police the same monster that killed the blonde. But the creature gets its new face, a handsome one, and spends his days admiring it in the mirror. Of course, he still can’t go outside, because Frankenstein had him murder a local kid, and the face of a local kid walking around on a different body would probably cause some confusion. So he tells Dr. Karlton that he plans to disassemble the creature and hide its body parts in trunks to be taken with him to his ancestral England, where the boy will not be recognised.

Meanwhile, Margaret is still going around nagging Frank into taking note of their upcoming wedding, which he will not hear of. During an argument, Margaret reveals to Frank that she knows what he keeps hidden in the basement. He tells her that he admires her spirit and is glad she knows, but behind her back, he instructs the creature to kill her, which it does. Frank and Karlton then prepare for their trip to England, and try to trick the creature into getting on the operating table so they can take him apart. But the creature realises something is wrong and kills Frank. The police arrive, and the creature accidentally electrocutes itself on one of those self-electrocution racks that every mad scientist has on their wall.

Background & Analysis

The 1950s saw the rise of the teenager. American International Pictures was among the first in Hollywood that realised to tap into this new, lucrative demographic. In 1957, with producer Herman Cohen in a central position, AIP merged their two cash cows, the science fiction movie and the teen movie, in I Was a Teenage Werewolf. The film is a surprisingly good low-budget effort that successfully managed to explore teenage angst within the SF/horror frame. I have written at some length about the rise of the teenager as a social phenomenon, and the way in which Hollywood latched onto the teen demographic, in my review of I Was a Teenage Werewolf, so head over there if you’re interested in digging deeper into that issue.

With the not completely unexpected success of that movie, AIP was not slow to plan a follow-up. By this time, Hammer’s reinvention of The Curse of Frankenstein had reached American shores, and it was a logical step for AIP to choose Mary Shelley’s classic for their next project (not that much of Shelley’s work survives in this adaptation). Cohen tells film historian Tom Weaver that the film was made in a rush and on a tight schedule. I Was a Teenage Werewolf had been such a hit that Texas distributor Interstate told Cohen that if he could come up with another film like that, Interstate would give him the Thanksgiving premiere date at their flagship Texas theatre, which left Cohen and AIP only four weeks time before they would have to start shooting. Cohen and director Herbert Strock also shot the accompanying feature, Blood of Dracula, back to back with I Was a Teenage Frankenstein.

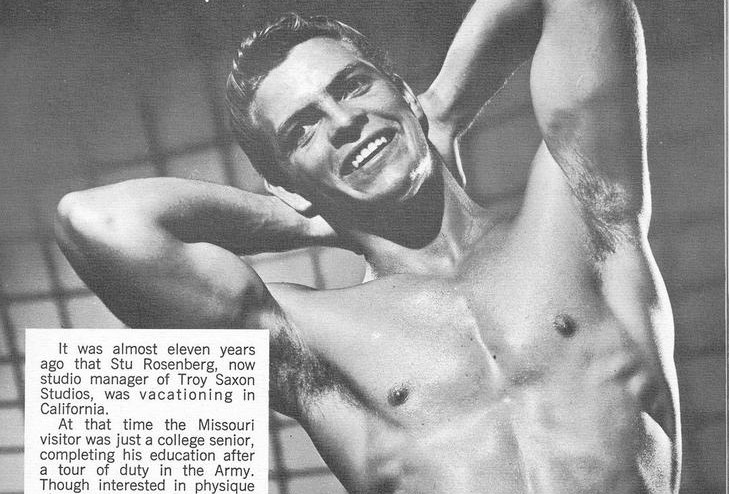

Whit Bissell had done a good job as the mad scientist in I Was a Teenage Werewolf, so he was a natural choice to play Professor Frankenstein. Beefcake Gary Conway was an art student working as a bouncer at local wrestling shows when Roger Corman cast him in … (deep breath) The Saga of the Viking Women and and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent in 1957. He tells Tom Weaver that it was probably this casting that gave him the opportunity to play the monster. Phyllis Coates was a good actress that never made the A-list, and was ping-ponging between B-movies and TV, and had appeared in an AIP “girls in prison” movie in 1956.

It seems clear that Herman Cohen and Aben Kandel fired off their best ideas in I Was a Teenage Werewolf. The script for I Was a Teenage Frankenstein has none of the originality or piognancy of the former movie, and is written with tongue firmly in cheek, with Whit Bissell firing off a barrage of deliciously hilarious lines like “Speak. I know you have a civil tongue in your head because I sewed it back myself.” and “In this laboratory there is no death until I declare it so.” But this doesn’t help much, as the story itself is so lacklustre and slow-moving, constantly interrupted by the quarreling between Frankenstein (who seems to lack a first name) and Margaret (who lacks a last name). The monster itself is given no personality whatsoever, apart from being a teenager who doesn’t like to be locked up, which makes it impossible for the audience to work up any sort of sympathy for him. Dr. Frankenstein is portrayed as so uniformly evil that it’s difficult to take the character seriously. It also strains credulity that Margaret, who seems a resourceful, smart and independent woman, continues to stick by her obnoxious fiancé when he treats her like dirt, throws their upcoming marriage in her face and keeps human experiments hidden in their common basement without telling her about it.

The hilarious lines and the overtly laughable plot elements, like Dr. Frankenstein having a morgue and an alligator pit in his rented house, or the car crash occuring right on his doorstep the very second he mentions needing a fresh teenage body (talk about manna from heaven), does make one suspect that Aben Kandel was actually writing a satire on the very film he was tasked with writing. If this was the case, then it went unnoticed by both Cohen and Strock. Which is probably for the best: if Strock had attempted to direct it like a comedy, the film would have been unbearable. As it is, he directs it completely straight, which gives the – clearly intentional – comical elements a sly wink-wink-nudge-nudge quality.

This doesn’t make it a good film, though. Despite its short 82-minute running time, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein lumbers extremely slowly during the first two thirds. It’s not that nothing happens per se, it’s that everything that happens is treated with a sort of blasé neutrality. The whole business of stitching the creature’s body together is done with a dispassionate detachment. There’s no feeling of drama, no great “it’s alive!” moment. At one point the finished body simply appears on a slab, with Frankenstein prosaically greeting it with a “Good morning”, in a sort of berating tone, as if he was adressing a teenager who had one beer too many last night. The film does pick up steam in the last third, but by then it’s a little too late.

The film was shot in seven days on a budget of $70,000. The movie is entirely studio-bound, more or less contained to three or four nondescript sets. Herbert Strock’s direction is flat and uninteresting, even though he tries to do something for the mood with the lighting. In an interview with Mark McGee, Strock seems aware of the film’s flaws, but says there wasn’t much he could do with the “lousy script”. All involved seem to have been somewhat embarrased with the movie. Cohen and Kandel wrote the script under pseudonym, and Gary Conway, whose real name was Gareth Carmody, changed his screen name as to not have the movie hanging around his neck as a lodestone in the future – he was, in his own words, “a serious art student”. For some reason, the film’s last shot of the creature getting electrocuted is filmed in colour.

If you want to find a theme to the movie, then it is that of the adult authority figure tyrannically imposing his will and ambition on a susceptible youngster. This theme of an evil adult turning a impressionable teenager into a monster was a theme that Cohen used in no less than six movies. While this was not, per se, a bad analogy to the teenage experience in the 50s, or perhaps even today, it was handled much better in I Was a Teenage Werewolf.

The monster’s makeup has gotten a lot of flack over the years. For a super-low-budget film, I think it gets the job done, and it is certainly sufficiently revolting, even if the one bulging rubber eye is somewhat comically over the top. Cohen says that the mask was done as an appliance in four parts, and Conway remembers that it required rather long sessions in the makeup chair. Over the years, the image of the teenage “Frankenstein” has become almost as iconic as that of the teenage werewolf. If Michael Landon in the previous role was channelling James Dean, then Gary Conway, with his muscular build, rectangular face, slacks and tight-fitting t-shirt bears a slight familiar resemblence to a young Marlon Brando, which was probably one of the reasons he was cast.

The music by Paul Dunlap is a bit intreresting, helping to create what mood the film has. Dunlap has written a fairly simple but functioning score, sometimes with isolated piano and horns in classical chamber arrangements, at times almost verging on mellow jazz.

I Was a Teenage Frankenstein is saved by its final third, without which it would be one of the dreariest science fiction films of the 50s. Granted, there is some enjoyment to be had from the first two thirds if you watch it as a satire on 50s mad scientist movies. The acting is not to blame for the film’s faults. Whit Bissell is in sharp form, seasoned Phyllis Coates gives a routine performance, but routine for her is always good, and Gary Conway, despite having precious little to work with, does what is required of him, while Robert Burton provides competent support as the assistant. Nevertheless, it is, for most of its running time, something of a snoozefest.

Reception & Legacy

AIP had hoped for another spectacular success with I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. The movie did a decent profit for the studio, but wasn’t nearly as popular as I Was a Teenage Werewolf. Nevertheless, Teenage Frankenstein became the blueprint for a whole slew of similar films produced by AIP in the late 50s and early 60s, several of which were produced by Cohen.

Upon its release, New York Times critic Richard Nason called the movie “abhorrent” and accused it for “[aggravating] the mass social sickness euphemistically termed ‘juvenile delinquency’”. Trade papers largely dismissed it as yet another teenage monster programmer with little new to offer, but noted that the movie had good exploitation possibilities for exhibitors. The Film Bulletin, not sitting on the same high moral horses as the NY Times, stated the film provided “shadows, gore and harmless hokum”, and Harrison’s Reports said that despite being “just so much claptrap”, the film offered plenty of action that horror-hungry teens would enjoy – even if photography “ranges from good to so-so”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy writes positively about Kandel’s “quirky screenplay”, the “excellent makeup” and the climax in “glorious colour”. He concludes that the film “remains watchable because Kandel’s script, though sadly not Strock’s direction which is pedestrian, has an element of parody about it”. Film critic Leonard Maltin dismissed it as “campy junk”. Critic and film historian Bill Warren writes; “As it is, few people will ever really enjoy Teenage Frankenstein, but that quirky script is still hiding behind this silly facade. Not that it really works (many long, pointless scenes lead nowhere) but the few gags at least make I Was a Teenage Frankenstein more enjoyable than the title alone could indicate.”

Today the film has a 5.1/10 rating on IMDb, based on 1,000 votes, a 2.9/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on over 700 votes and a 4.5/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes, with a rather poor 30 percent “freshness” rating.

There is one person in the world that thinks Teenage Frankenstein is better than Teenage Werewolf, and that is Richard Scheib at Moria, who gives it 3/5 stars: “I Was a Teenage Frankenstein is played considerably more tongue-in-cheek than Teenage Werewolf and emerges as the better of the two films as a result.” Christopher Stewardson at OurCulture is also something of a defender: “Flatly directed, statically shot, but with enough pseudo-scientific positing to enjoy, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein is strangely enjoyable. Whilst this is not a well-made film, one can certainly find gleeful entertainment in its gruesome aesthetics.” Jon Davidson at Midnite Reviews gives it 5/10 stars, writing: “Combining monster mayhem, mad scientists, and an alligator with a palate for human flesh, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein is a ridiculous and mediocre creature feature. Nevertheless, this film benefits from the performances of Gary Conway, Phyllis Coates, and Whit Bissell“. Lisa Marie Bowman at Horror Critic isn’t enthralled: “Unfortunately, while the monster makeup is indeed impressive, I Was A Teenage Frankenstein is never as much fun as I Was A Teenage Werewolf. While the teenage werewolf had an entire town to explore, Teenage Frankenstein is pretty much stuck in that lab. Whereas the teenage werewolf spent his movie running wild, Teenage Frankenstein spends all of his time doing whatever the professor orders him to do. As a result, I Was A Teenage Frankenstein is a much slower film and also lacks the rebellious subtext of I Was A Teenage Werewolf.“

While it was I Was a Teenage Werewolf that started the “I Was a Teenage …” trend, later movies in the subgenre were more closely modelled on (and spoofed) the formula laid out in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, a formula which itself adhered closer to the mad scientist films of the 40’s that to the somewhat original take of Werewolf. It’s difficult not to believe that the homoerotic relationship between Frank N. Furter and his buff creation Rocky in the cult musical The Rocky Horror Show (1973) and its 1975 film adaption would not be partly inspired by the scene in which Whit Bissell almost leeringly admires the physique of his teenage creation, as it is lifting weights. Another cultural legacy is Alice Cooper’s 1986 minor hit “Teenage Frankenstein” off the record Constrictor.

Cast & Crew

Herbert Strock was a respected editor with some TV directorial experience when he was assigned to edit Ivan Tors‘ and Curt Siodmak’s SF movie The Magnetic Monster (review). According to some sources, he took over directorial duties as Siodmak wasn’t comfortable with the technical aspects of directing. However, there are diferrings claims on whether or not this was actually the case. Strock also edited another Siodmak film, Donovan’s Brain (1954, review), and, according to himself, talked producer Tom Gries out of firing Siodmak. Here, Strock still ended up directing second unit. Strock did replace Siodmak when Siodmak had written and directed a TV series in Sweden, called 13 Demon Street (1959). However, when the episodes were finished, the studio thought most of them were too bad to release. So Strock got called in again, to re-edit three of them into a feature film called The Devil’s Messenger (1961).

Herbert Strock later ended up directing parts of Riders to the Stars (1954, review), again uncredited, when star and director Richard Carlson felt uneasy about directing the scenes he appeared in himself. The robot film Gog (1954, review) was Strock’s first credited feature film direction. He later directed a number of B horror and SF, like, Blood of Dracula (1957), I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), The Crawling Hand (1963) and Monster (1980), and he also wrote the latter two. He edited and produced a number of these films.

Producer Herman Cohen worked his way up the career ladder in the movie business from a young age — he began as a gofer in a movie theatre as a child and by the age of 15 he was well on his way to becoming a theatre manager. At the age of 25, in 1951, he produced his first film, The Bushwackers, and during the first half of the 50’s produced and sometimes co-wrote (often with Aben Kandel) around a dozen low-budget movies, including the abysmal Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (1952, review), and the slightly better post-apocalyptic thriller Target Earth (1954, review). In 1954 he was approached by James Nicholson who offered him to become a partner in the new movie company ARC, which later became AIP, but Cohen was tied up with obligations to United Artists. Nicholson instead founded the company with lawyer Sam Arkoff. Nevertheless, it was AIP that gave Cohen his greatest success, starting with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), and following up with I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), Blood of Dracula (1957) and How to Make a Monster (1958, review). He then relocated to the UK, where he produced such films as Konga (1961), Berserk (1967) and Trog (1970). He gradually moved more into distributing than producing, and in 1981 formed the distribution company Cobra Media. He passed away in 2002.

Romanian immigrant Aben Kandel started his career as a novelist in 1927, and also began writing plays. His 1931 hit play Hot Money was turned into films in 1932 and 1936, and one of his short stories was filmed in 1934, and one of his novels in 1940. He wrote his first screenplay in 1935. He wrote over a dozen screenplays in the 30’s, 40’s and early fifties, when he began writing for TV and struck up his long partnership with Herman Cohen. He co-wrote most of Cohen’s movies, which is what he is best remebered for today.

Whit Bissell is known to friends fifties horror and SF films as the eternal straight-laced, often mild-mannered and competent scientist, physician, government official or military man. He is best known to a wider audience for one of his rare villainous roles, that of the evil scientists who turns Michael Landon into a werewolf in I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). But his SF credit sheet is a mile long, and memorable performances include Dr. Thompson in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), a small but important role as one of the time traveller’s sceptical friends in George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960) and his portrayal of the evil Governor Santini in Soylent Green (1973). He also appeared in a small role in Lost Continent (1951, review), played a military scientist in Target Earth (1954, review), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), reprised his villain in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), appeared in Jack Arnold’s Monster on the Campus (1958, review), played Dr. Holmes in Irvin Allen’s TV movie City Beneath the Sea and reprised his role in a TV remake of The Time Machine (1978). Bissell was also a familiar face in science fiction TV from the fifties onward, appearing in many anthology shows, such as Out There and Science Fiction Theatre. His most prominent SF role was that of Lt. Gen. Heywood Kirk, one of the main characters of the TV series The Time Tunnel (1966-1967). Other memorable SF moments on TV for Bissell are the 1959 Christmas episode of Men into Space, the injured navy captain at the heart of the One Step Beyond episode Brainwave (1959), as small role as commanding officer in The Outer Limits episode Nightmare (1963), guest starring a young Martin Sheen, Mr. Lurry, the station Manager of the space station involved in the legendary Star Trek episode The Trouble with Tribbles (1967), and as one of the scientists studying the captured Hulk in The Incredible Hulk episode Prometheus: Part II (1980).

Phyllis Coates (b. 1927) got her start in showbiz doing vaudeville, graduating from chorus girls to doing comedic skits. She began her film career in the late 40s doing comedy shorts, and soon began appearing in uncredited bit-parts in feature films. Coates was extremely busy during the early fifties, doing over dozen appearances in films and occasionally TV each year in 1949 through 1953. In 1951 she was cast as Lois Lane in the Superman pilot, released as the film Superman and the Mole Men (review), and she played the role during the first season of the TV show The Adventures of Superman, before being replaced by Noel Neill (who had played the role in the previous film serial).

Coates continued her career playing leads in B-movies, most of them westerns, and increasingly as a guest star on TV shows. She starred in the crappy Invasion U.S.A. (1952, review) Republic’s Jungle Drums of Africa (1953) and Panther Girl of the Congo (1955), opposite SF legend Richard Denning, as well as AIP’s Girls in Prison (1956). After I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957), she also appeared in Jerry Warren’s The Incredible Petrified World (1959). She went into semi-retirement in the mid-60s, but occasionally returned to the screen over the coming decades.

Gary Conway was an art student at UCLA who was regularly seen in University plays and worked as a bouncer in the evenings. He tells Tom Weaver that an agent had spotted him and suggested he go and seen AIP about a role in the upcoming The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Journey to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent (1957). He got a role, and on the strength of that, got cast as the creature in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. The studio apparently thought his real name, Gareth Carmody, was too refined, which suited Conway well, as he was a serious art student and didn’t feel like having the AIP movies coming back to haunt him in the future, so a change to Cary Conway was a good solution for both parties.

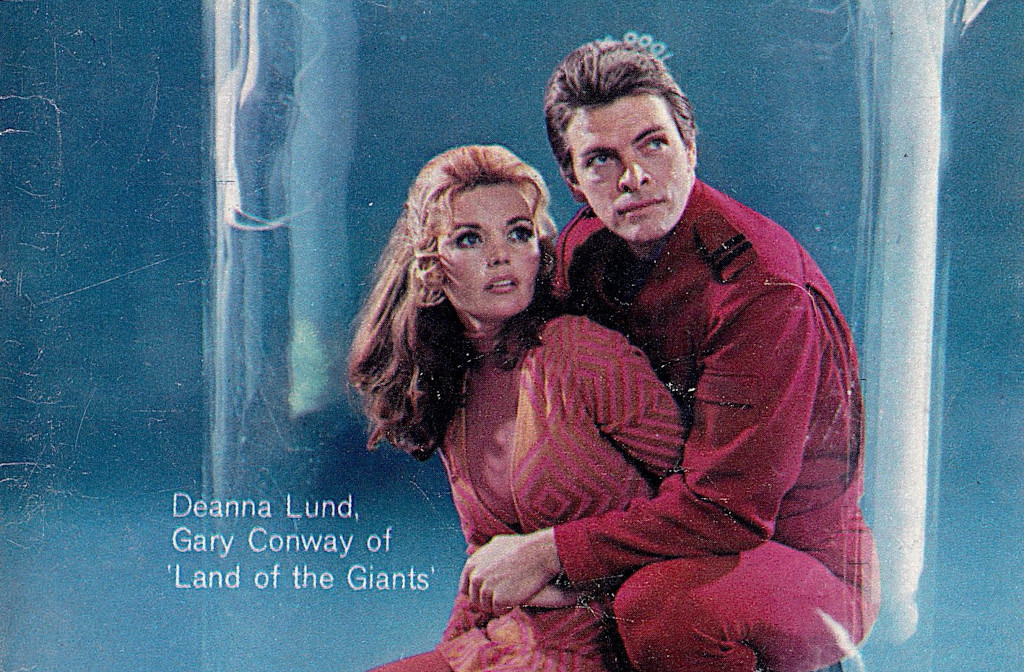

Conway reprised his role as the creature in the film’s follow-up How to Make a Monster (1958), but that was the end of his association with AIP. He transitioned to TV, where he did guest spots in a number of TV shows through the 50s and 60s, and continued to act sporadically in the 80s and 90s. He is probably best remembered for starring in the lead in the TV show Land of the Giants (1968-1979). Conway was married to Miss America 1957, Marian McKnight, and together then ran a winery, which they eventually sold for a decent profit. In latter years, Conway moved into the production and distribution side of the movie business, wrote a couple of films and even directed one in 2000. This remained his last movie project – to date. As of February, 2024, he is still alive at the respectful age of 95. While happy to have changed his name, Conway tells Weaver he feels very fondly about his old monster movies, and that, despite all their shortcomings, they have stood the test of time.

Janne Wass

I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. Directed by Herbert Strock. Written by Aben Kandel & Herman Cohen. Starring: Will Bissett, Phyllis Coates, Cary Conway, Robert Burton, George Lynn, John Cliff, Marshall Bradford, Claudia Bryar, Angela Austin, Russ Whiteman. Music: Paul Dunlap. Cinematography: Lothtrop Worth. Editing: Jerry Young. Art direction: Leslie Thomas. Makeup: Philip Sheer. Sound: Al Overton. Procuced by Herman Cohen for Santa Rosa Productions & AIP.

Leave a reply to Kevin Olzak Cancel reply