A scorned heiress is abducted by a UFO and grows to gigantic proportions, while her cheating husband tries to murder her so he can run off with the town floozy. Nathan Juran’s 1958 cult classic is bad in many ways, but its themes continue to fascinate. 6/10

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. 1958, USA. Directed by Nathan Juran. Written by Mark Hanna. Starring: Allison Hayes, William Hudson, Yvette Vickers. Produced by Bernard Woolner. IMDb: 5.0/10. Letterboxd: 2.6/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 6.2/10. Metacritic: N/A.

Poor Nancy Archer (Allison Hayes) is in a sticky situation. A millionaire heiress, she has moved out of the city to a desert smalltown with her sleazebag husband Harry (William Hudson), who spends all his time philandering with local floozy Honey Parker (Yvette Vickers). With a history of nervous breakdowns and alcoholism, Nancy is the laughing stock of the town, and when one night she sees a giant satellite parked on the highway and a 30 foot alien giant (Michael Ross) reaching out for her diamond necklace, no-one believes her, even if the lawmen (George Douglas, Frank Chase) play along, only because “she pays most of the town’s taxes”.

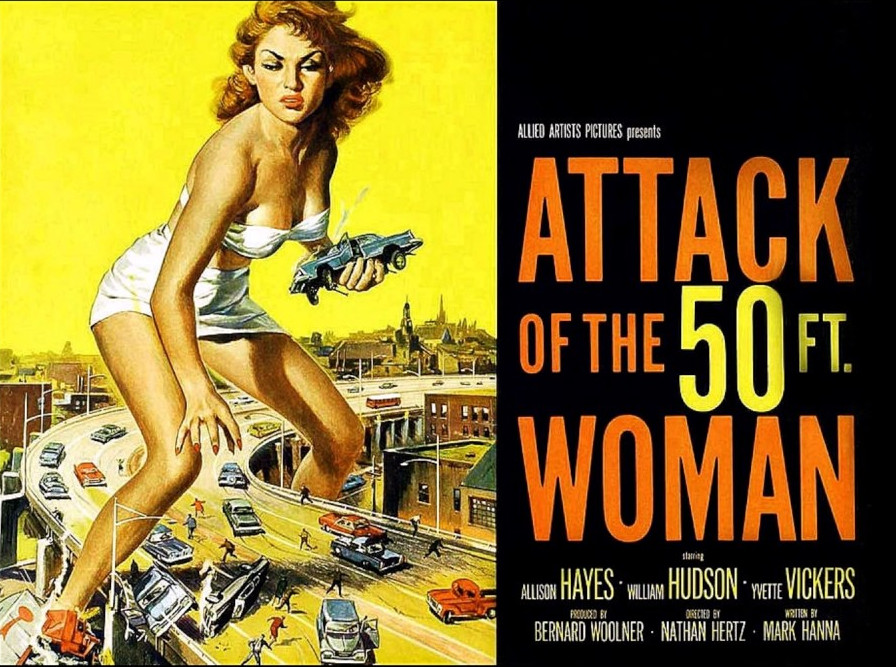

That’s the intro to Nathan Juran’s 1958 cult classic Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, a movie made solely for the drive-in audience of the late 50s, to cash in on the success of Bert I. Gordon’s giant films The Cyclops (1957, review) and The Amazing Colossal Man (1957, review). Reynold Brown’s fantastic poster stands alongside MGM’s poster for Forbidden Planet (1956, review) as one of the most iconic images of 50s science fiction. The movie was produced by the Woolner Brothers, with Jacques Marquette as executive producer, and distributed by Allied Artists, who were increasingly starting to give American International Pictures a run for their money concerning the teen audience in the late 50s.

Hi and welcome back to the blog. I apologise for the long pause – it’s been record hot in Finland this May, and literally one day of rain in the whole month, which mean’s I’ve spent all my free time getting my allotment garden ship-shape. Let’s hope for a cold and rainy June, so I can put some more effort into my movie reviews.

Back to the film: Spurred on by Honey, Harry sees his chance to have Nancy locked up in the loony bin, and calls Nancy’s psychiatrist (Roy Gordon), who proclaims she is on the verge of another breakdown. The next morning word of Nancy’s giant spotting has gotten around and even the TV newscaster (Dale Tate) mocks her. Nevertheless, she forces Harry to drive out with her in the desert to look for the giant – which they eventually find. Harry fires his gun at the giant and flees, leaving Nancy behind. Instead of warning the authorities that there actually is a 30-foot alien giant rampaging outside town, he plans on leaving town with Honey. However, he is caught red-handed by Nancy’s faithful butler Jess (Ken Terrell), who calls the sheriff on the conniving couple.

The next morning Nancy is found with strange bluish scratches on her neck and her diamond necklace missing. Harry still refuses to divulge the fact that the spaceship and the giant are real – but the lawmen find it suspicious that he’s driven Nancy out to the desert and abandoned her, and tell him not to leave town. Instead, Harry now plans to use Nancy’s medicine to give her a lethal overdose in the night. But when he arrives at her bedroom he is met by a shocking sight: Nancy has grown to 50 feet tall)! Or at least that is what is indicated by the giant prop hand, which is all we see.

Specialist Dr. von Loeb (Otto Waldis) is called in, and he is at a loss for an explanation, but it has something to do with radiation. Meat hooks and chains are ordered in, and Nancy is chained to her bedroom (or at least her hand is). The sheriff and Jess follow a path of giant footprints into the desert where they find the “satellite”, and enter it. Inside strange glass spheres they see a collection of diamonds, including Nancy’s necklace, and decuce that they must be used to power the spaceship. They are attacked by the giant, who wrecks their car, but they escape on foot, and are eventually picked up by the goofy deputy.

Meanwhile, Nancy has woken up and is now intent on getting to Harry, who is, as usual, necking Honey at the local watering hole. Nancy breaks out of her chains and her mansion and goes on the prowl, eventually tracking down Harry and Honey at the local hotel bar. Tearing up the roof of the hotel, she throws a roof beam at Honey, killing her instantly, and picks up Harry. The sheriff opens fire at a power line transformer, which blows up and kills Nancy. The doctor examines Harry and finds that Nancy has squeezed him to death. “She finally got him all to herself”, he comments laconically. The end.

Background & Analysis

Giant monsters had been a fad throughout the 50s, but generally in the form of dinosaurs, robots and bugs. In 1957, Universal reveresed the trend with The Incredible Shrinking Man (review), but paradoxically created a new fad of giant people. The “master” of these BIG pictures was low-budget “auteur” Bert I. Gordon, who made three movies featuring a bald-headed, lumbering giant in diapers, The Cyclops (1957, review), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957, review) and War of the Colossal Beast (1958, review) – as well as the miniature people film Attack of the Puppet People (1958, review).

Based out of New Orleans, three brothers, Bernard, David and Lawrence Woolner, owned two drive-in theatres, and had dabbled in movie producing before. The three had seen the success of these kind of pictures at the drive-ins, and had a mind to cash in on their popularity not just as exhibitors but also as producers. They contacted cinematographer and producer Jacques Marquette, who in 1957 had a hit with the low-budget SF thriller The Brain from Planet Arous (1957, review), who had ties to Allied Artists. In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, Marquette says that it was Bernard Woolner who came up with the idea of turning the giant menace into a scantily clad woman, rather than Bert I. Gordon’s lumbering, diaper-wearing man (even if the bald giant features in the movie as the alien).

Marquette contacted his friend Mark Hanna, who had written or co-written a number of scripts for American International Pictures, including The Amazing Colossal Man. Marquette seems to have been the de facto producer of the movie, even if the Woolner Brothers were credited with producing, and Marquette stood as executive producer. At least Marquette seems to have been in charge of choosing his crew and casting. For his director, he chose Nathan Juran, with whom he had collaborated on The Brain from Planet Arous (1958, review). Like with that film, Juran chose to be credited under the pseudonym of Nathan Hertz, perhaps feeling these films were not the best examples to feature on his CV. Marquette also took on the duties of cinematographer. No art director was credited, so one can assume that Juran, whose background was in art direction, doubled as such, saving money on yet another job. Neither is there a credited special effects team, so one assumes that Marquette and Juran handled that as well. And as with The Brain from Planet Arous, Marquette cobbled together a reasonably cheap but very good cast, headlined by exploitation film starlets Allison Hayes and Yvette Vickers.

The budget of the film was, according to different recollections of those involved, between $65,000 and $89,000, with an extra $10,000 slapped on by the producers just because they were afraid Allied Artists were going to feel it was too cheap. The shooting schedule was eight days, and the entirety of the film was shot in Los Angeles. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Yvette Vickers says that a lot of it was filmed, including the bar and bedroom sequences, in “a studio at Cahuenga Boulevard”, and Nancy Archer’s mansion was a big empty house in Beverly Hills, that the crew rented for $500 a day. Jacques Marquette told Weaver that the outdoor shooting mostly took place in a canyon near his home in the Tarzana suburb. The movie was filmed under the working title “The Astounding Colossal Woman”.

The movie features what for some reason became the staple setting for 50s science fiction movies, the South-West American desert small town. The setting was established by Ray Bradbury in his script for It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), a symbol for sleepy Americana upset by change and threat. Over the years, the symbolism gradually disappeared, and like much in SF movies, the setting became a trope. And of course, it was a cheap setting to film in.

Nevertheless, you can find some topicality in Mark Hanna’s script for Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. The advertised attack doesn’t take up more then 10 minutes of the movie at the very end, nor does the 50 foot woman show up until that time – unless you count a few brief glimpses of the famously bad giant hand prop. For most of its running time the film explores the breakdown of an American marriage, and one can see it as a comment on the draconian divorce laws of the 50s, legally propping up unions that were clearly doomed, and that brought only unhappiness to all involved. Attack of the 50 Foot Woman is one of those films that divide audiences over its message. Some regard it as a deeply misogynist film, others find in it a kernel of feminist thought.

And it is true that hard-drinking, clingy Nancy Archer who refuses to let go of her husband although no-one benefits from their marriage, isn’t portrayed in a particularly positive light. For example, critic Robin Bailes at Dark Corners suggests that the the movie is taking Harry Archer’s side, condoning Harry’s adultery as an inevitable result of Nancy’s drinking and mental health problems: Bailes seems to say that the film wants us to see Harry as the victim and Nancy as the villain. And while Nancy surely doesn’t cut a figure as the usual 50s ingenue, I’m not sure that Bailes gives Hanna’s script enough credit for complexity. While many of the 50s SF movie heroes are written as dickheads, despite the fact that we are supposed to root for them, I can’t see that Hanna wants us to sympathise with Harry Archer. When Harry contemplates to murder his wife, he clearly crosses the line from dickhead to villain. If anything, the movie gives Nancy a perfectly good reason for being upset – Harry does spend most of his time down at the local bar – or at the local motel – with floozy Honey. All in all, Harry Archer has few redeeming qualities, and when the film does show him in a positive light, it quickly pulls the rug from under this by revealing that his seemingly kind-hearted behavior towards Nancy is only a ruse to control her. On the other hand, you can also view Harry as a victim of two manipulating women. It is Honey Parker that eggs Harry on in his plans to kill Nancy – but it is difficult to see Harry as blameless in the matter. It’s not like he need much coaxing in the first place.

What you make of the film’s gender politics depends on how you view Nancy Archer, the 50 foot woman. Is she the victim that in the end rises up to take her just revenge on Harry and Honey? Or does her size change simply unleash the monster she really is, finally sprung into its ultimate form? I personally find it hard to swallow the latter conclusion, as a monster would need a counterbalancing hero in order for the monster movie formula to work. And neither Harry nor Honey can be viewed as heroes, however you look at it. In the age-old tradition of King Kong, the giant monster is a character that you are ultimately meant to feel sympathy for. My interpretation is that the demise of Nancy Archer is a moment that is at least supposed to elicit a pang of sadness. Whether the film succeeds in this is another matter.

Whatever you make of it, the unusually involved and fleshed-out character drama at the heart of Attack of the 50 Foot Woman makes the film a refreshing anomaly in the canon of late 50s science fiction movies. If you look at it more as a conventional drama than through the monster movie tropes, one can view Nancy’s growth as a metaphor for her illness. In the end, thus, it is not Nancy that grows 50 feet tall, but her illness that takes on monstrous proportions. Or perhaps it can be seen as a metaphor for all the darkness and misery caused by the unhealthy relationship between Nancy and Harry, eventually destroying them both.

Mark Hanna’s writing isn’t exactly Man Booker-prizeworthy, and a better writer – say, like Richard Matheson, could have made more of the dramatic possibilities inherent in the material. But the drama is what carries the movie, and it is helped by a couple of – if not well-rounded, then at least interesting characters. Nancy, Harry and Honey make a great leading trio, all with well-defined motivations and personalities.

On the other hand, the science fiction material here is rather weak and seems to be cobbled together in order to cash in on not one, bit two of the big trends of 1958: gigantism and satellites. The film was released in May, 1958, some eight months after the launch of Sputnik (and four months after Sputnik burned up in the Earth’s atmosphere), and satellites were still the talk of the town. Not that there are any satellites in the film – there is an alien spaceship, which the characters insist on calling a satellite, seemingly forgetting the the most important element of a satellite: it circles a heavenly body. It does not drive around haphazardly in a California desert.

The giant alien is never explained (why is he here, what does he want?), and after the sheriff and Jess unsuccessfully try to take him out with grenades, he just sort of disappears from the story. His interest in Nancy is her diamond necklace, which, it is speculated, helps power the spaceship. Why her encounter with the alien causes her to grow to 50 feet is never explained, either, although Dr. Von Loeb throws a number of theories in the air, at one point even suggesting that menopause has something to do with it. It’s something to do with radiation, we are told, but exactly how and why Nancy was exposed to radiation remains a mystery. It is clear the script was written in a haste, as screenwriter Mark Hanna hasn’t even attempted to give any coherent explanation to the extraordinary happenings in the movie. Unfortunately, his rambling autobiography doesn’t give any clues to his writing progress, as he barely even mentions Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, despite it being his best known film by far – he even put it in the title of his autobiography.

As stated, the 50 foot woman doesn’t really appear until the last 10 minutes of the movie, when she tears up the roof of the bar in which Harry and Honey are boozing and kills them both, before being blown up by the sheriff. This is Allison Hayes’ star moment. The few minutes when she appears as a giant in a white bikini-like outfit are movie legend. Not that the footage itself is particularly noteworthy – much of it consists of the same shot of Hayes walking, filmed in slow-motion, across the screen, at one time even flipped as to hide the fact that it is just the same footage used for the fourth time. In each shot she is superimposed over a different backdrop – sometimes partly translucent, other not. Her size seems to differ wildly from shot to shot, as the background footage hasn’t been filmed accordingly. At some points she seems not much taller than 10 feet, barely reaching the roof of a one-story building, while at other times she seems close to the adverised 50 feet.

The slow-motion footage is supposed to give Nancy a feeling of enormous proportion, but it doesn’t quite work, as she is never filmed with normal-size actors in the same frame. Instead the slowed-down footage just gives her a sort of drowsy appearance. On the other hand, the miniature footage of Hayes tearing through the roof of the bar is actually quite well realised. The giant prop hand is one of the worst props in SF movie history, a wrinkled and puffy prop looking like something out of a school play. Matters are made better by the fact that it sometimes fills the entire screen in all its hilarious glory.

The footage of the giant alien is particularly bad, with the alien walking through the film at least 50 percent translucent, and particularly poorly superimposed on the background footage. Bert I. Gordon is usually called out for the worst special effects of 50s SF movies, but this footage in Attack of the 50 Foot Woman is even worse. In a later interview, executive producer Jacques Marquette (who also handled photography) claimed that the translucense was intended, but I have my doubts. If so, why does no-one who sees the giant ever mention the fact that he is translucent?

Tom Weaver asks Marquette in an interview why the decision was made to spoof up the film, after Marquette hade made a couple of serious science fiction movies. Marquette says that there was no spoofing intended. I think this is quite clear when watching the movie. It is not a spoof, it’s just that it is, occasionally, extremely bad – in particular when any special effects are involved.

The acting, however, is not bad at all. Both Allison Hayes and Yvette Vickers were very good actors, and do a lot to make Attack of the 50 Foot Woman an enjoyable movie. Vickers, in particular, is gloriously naughty as the manipulative, sex-oozing bad girl. For a lot of the adolescent kids in the audience, a scene where Vickers grabs William Hudson and kisses him, this was probably the first time they saw an open-mouthed kiss. Vickers never plays the town slut like a charicature, but gives Honey Parker a groundedness and realism that does a lot to sell the somewhat implausible lines that comes out of her mouth, such as when she casually suggests that Harry kill his wife. Allison Hayes, another actress that usually emitted a natural sexiness, is also very good as the troubled Nancy Archer, lending the character real depth and emotional subtlety. William Hudson was a steady-working bit-part actor who was thrust into leading man status thanks to science fiction movies, and he comes off with flying colours here, no doubt helped by his superb co-stars. Hudson’s Harry is a real slimebag, and one can imagine him oiling his way into the bed of millionaire heiress Nancy, before dumping her once he got his marriage and money.

This trio of actors make Attack of the 50 Foot Woman a better film that it has any right to be, and they are backed by an equally good supporting cast. George Douglas gives a level-headed performance as the sheriff, and Frank Chase is particularly good as his comic sidekick deputy. That is, Chase is simply too good an actor for the dumb role of the block-headed deputy, and he knows it. Instead of playing the role like a golly-goodness vaudeville schtick, Chase inserts a warmth and emotional intelligence into the character, making him instantly likeable. Ken Terrell is a calm and, likewise, highly sympathetic presence in the film, even getting a hero moment when he wrestles Harry trying to escape town. Otto Waldis brings a bit of colour to the proceedings, reprising his staple role of the German scientist from previous 50s SF outings.

Nathan Juran is also a good enough director to make the most of the film’s low budget. As in his previous movie for Jacques Marquette, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957, review), he directs, if not snappily, then at least competently, with a few outstanding, quirky shots. He re-uses his gimmick of having actors’ faces distorted through see-through containers. In The Brain from Planet Arous it was John Agar who had his face distorted through a water cooler, and here it’s Douglas and Terrell’s face getting “enhanced” through the globular glass containers containing the diamonds in the spaceship. The effect is even more striking here, but is perhaps milked a little too long. In general, the scene inside the spaceship is one of the most effective in the movie, building some real atmosphere and tension. The ship’s interior is just simply perforated sheets of metal and lots of smoke, but Juran films it well. Nevertheless, the films he made for Marquette he apparently deemed too bad to attach his own name to, and was credited as Nathan Hertz (his full name was Nathan Hertz Juran).

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman is a weird film. It’s based on a script with more holes than a Swiss cheese, with an SF premise that seems little more than an afterthought to the film’s exploitation premise, and with bits and pieces that are so ridiculous it feels like a spoof, although it isn’t. The badness of the film is primarily derived from its ultra-shoddy effects work, some of the worst seen in a generally released science fiction movie in the 50s- Nevertheless, it has some dramatic content that stands head and shoulders over most films of its ilk, decent direction and splendid acting. And the film has remained a cult classic almost despite itself. Not just one that is laughed at, but one that is referenced, debated and analysed even to this day — see for example the references to the film in 2023’s Hollywood blockbuster movie Barbie (a film that for all its supposed originality owes a huge debt to 50s B-movies). While the execution of Attack of the 50 Foot Woman is shoddy, its thematic foundations are strong enough to make it stand out — positively — among much of the brainless exploitation churned out in the late 50s.

Reception & Legacy

When the film was screened for Allied Artists execs, they were appalled at the shoddiness of the effects. They reminded the producers that the film had come in under budget, and that there was till $10,000 left, and demanded the crew get back to re-shoot the effects. Jacques Marquette said that this couldn’t be done for $10,000, as they would have to get all the actors back and reshoot scenes from scratch, which would come in at double the prize. Bernard Woolner, for his part, had experience from the drive-in market, where the film was going to make most of its money anyway, and knew that the quality of the effects mattered little to the patrons. He told AA that nobody went to the drive-in to see art, but to hang out, make out and have fun. To most patrons, the movie was secondary. A title like Attack of the 50 Foot Woman would draw crowds, and whether the film was good or bad mattered little. AA was convinced, and the picture was released as was on May 18, 1958, on a double bill with Roger Corman’s War of the Satellites (review).

The film received lukewarm reviews in the trade press. Variety called it “a minor offering for the scifi trade”. Critic Whit noted good acting but deemed Juran’s direction “routine” and Hanna’s dialogue “corny”. The Film Bulletin wrote: “Nathan Hertz has directed this in rather lethargic and loose avenues. There is little suspense, the events being too farcical for that, and just as few trembles.” Harrison’s Reports thought that “little imagination has gone into the presentation of its fantastic and mildly interesting story. […] The direction and acting are so-so.”

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy writes: “Despite the corniness of Hanna’s screenplay and Juran’s plodding direction [Hayes’] size does have a curious fascination […] The special effects are dire”. Bill Warren in Keep Watching the Skies! says: “Attack of the 50 Foot Woman could have been the camp classic some find it, if it hadn’t been ponderous and flat. There are delightful moments through out, and it does have Allison Hayes and Yvette Vickers, virtues indeed. Although it is funny from time to time, and a total lack of logic makes it appealing in a surrealistic fashion, the movie has too many conventional defects to rise to the daffy heights of Cat-Women of the Moon, although it is probably a contender.”

The movie has a 5.0/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on over 6,000 votes, and a 2.6/10 rating on Letterboxd, likewise based on over 6,000 votes. Critics at Rotten Tomatoes give it 6.2/10 stars, and a 71% Fresh rating.

Today, many critics dismiss Attack of the 50 Foot Woman as one of the many so-bad-they’re-good B-movies of the late 50s. For example, TV Guide calls it a “really bad sci-fi film […] worth seeing for laughs”. Likewise, Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster in a fun review writes: “This is bad, cheesy Fifties giant monster Sci Fi goodness at its best, and it all combines into an hour of solid, goofy, Drive-in ready entertainment. It’s perfect for that midnight movie night, and has enough cheese to make that popcorn extra tasty. Or, to sum it all up: It’s fun.” And as Glenn Erickson argues at Trailers from Hell: it’s probably supposed to ne cheesy: “What makes Attack of the 50 Foot Woman so entertaining? The film seems aware that its audience will be thinking, ‘what kind of nonsense is this?’ even as it plays surprisingly well. The soap opera love triangle actually works, and Ms. Hayes’ murderous stroll as the Amazing Colossal Woman has an air of dignity outraged.”

On the other hand, Kevin Maher in a recent retro review at The Times gives the movie 4/5 stars, writing: “Yes, the effects are risible. And yes, the B-list director Nathan Hertz squeezes every possible second of screen time from a giant rubber hand and lots of screaming extras. But in the cultural moment when Barbie has been revamped as a totem of female empowerment this can only be seen as the original feminist doll movie.” And Bruce Eder at AllMovie writes; “Shot in less than two weeks, on a budget of under $100,000, the movie has been laughed at as a title and ridiculed as a film for more than 40 years, and not even the made-for-cable remake in 1993, starring Darryl Hannah, has done much to raise the reputation of the original. Yet Juran’s movie, with all of its flaws, has managed to keep its place in the hearts of cineastes and 1950s pop-culture enthusiasts for close to a half-century. The reason may lie in the currents that run through the fabric of its script and images, revealing aspects of the era in which it was produced that give it a power over viewers far greater than the cheap special effects. Those seeking an explanation must arrive at the conclusion — unfathomable at the outset — that Attack of the 50 Foot Woman is a far more thoughtful film on a subliminal level than its script or plot summary would lead one to believe.”

Cast & Crew

Brooklynite Jacques Marquette moved to Hollywood with his family when he was still a child in 1919, and from his early teens started working small jobs in the movie business, eventually becoming a cameraman in the 40s. As he explains to Tom Weaver, graduating from cameraman to director of photography in Hollywood was a bureaucratic process, as producers were obligied by union rules to choose from any and all cinematographers that were already available before “promoting” a cameraman to DP. That’s why he took matters into his own hands and in 1957 decided to become his own producer. He had been saving and raising a small amount of money for his own film, the drag race movie Teenage Thunder (1957), and somehow distribution company Howco got wind of it, and wanted to co-finance and distribute it. A minor hit, it prompted Howco to finance two more movies for Marquette Productions, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957, review) and Teenage Monster (1957, review), the latter which he also directed.

The Brain from Planet Arous was directed by Nathan Juran (under the pseudonym Nathan Hertz), and apparently he and Marquette had a good working relationship, as Juran went on to direct the two next (and last) movies that Marquette produced: Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) and Flight of the Lost Balloon (1961). The former, of course, has become a bona fide cult classic among SF fans. After this, Marquette had no need to produce his own films, as he was finally promoted to the status of director of photophy. He went on to steady work in the movies, and in his latter career, TV, and kept at until the late 80s. He also filmed the SF movies Last Woman on Earth (1960) and Varan the Unbelievable (1962), as well as a couple of SF TV movies and series.

Nathan Juran, born Naftali Hertz Juran in current-day Romania, moved to the US with his parents in 1912. He studied architecture and started his own firm, but with the constructing business grinding to a stop due to the Great Depression, he moved to Los Angeles in the late thirties, and started working in Hollywood’s art departments. During the 40’s he worked as an art director for 20th Century-Fox, was awarded an Oscar in 1942 for his work on How Green Was My Valley, and was nominated in 1946 for The Razor’s Edge. In 1949 he moved to Universal. When working on the horror film The Black Castle, he was asked to direct when the intended director dropped out two weeks before filming. Universal liked Juran’s work, and began giving him more directorial duties.

Juran primarily worked on B-westerns, but also the occasional costume swashbuckler. In 1957 he was assigned to his first science fiction movie, The Deadly Mantis (review). He then made a submarine movie starring Ronald Reagan for producer Charles Schneer at Columbia, which led Schneer, who had by then established his long-running collaboration with Ray Harryhausen, to assign Juran to work on the science fiction classic 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review). This led to Juran working on Schneer’s and Harryhausen’s first of many fantasy films based on classic Greek myth, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), which became both a box office and critical success. In 1962 he tried to recreate this success with Jack the Giant Killer, which he co-wrote and directed. However, the film received flack for its story, which blatantly ripped off the Harryhausen movie, and its stop-motion effects that deemed inferior to Harryhausen’s work.

Juran might have made a good living at Universal or another major studio, but wanted to get away from major studio restraints, and often worked for smaller outfits or independent producers, and had no qualms over accepting low-budget and schlock. In a later interview, he said he saw himself as a technician creating films for a living and not as an “artist”; “I always felt that my movies were temporary. They were just pieces of celluloid. You couldn’t eat them. You couldn’t sleep in them. You couldn’t use them in any practical way. So, I never really took the picture business too seriously.”

Apart from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Nathan Juran is best known for the four science fiction movies he directed during a span of two years in 1957 and 1958: The Deadly Mantis, 20 Million Miles to Earth, The Brain from Planet Arous (1958), and perhaps most famously, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). He returned to the genre (and Schneer) in 1964 with the H.G. Wells adaptation First Men in the Moon, co-written by Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale. He also directed episodes for a large number of SF TV series, particularly those produced by Irwin Allen. He directed his last film in 1973, before he returned to work in architecture.

Screenwriter Mark Hanna made his Hollywood writing debut with Roger Corman’s western Gunslinger in 1956. Hanna was born in Rhode Island, Florida in 1917, the son of Lebanese immigrants. In his biography, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman at Schwab’s Drugstore, Hanna writes that he started out as an actor, doing theatre at the Little Theater in Jacksonville, Florida, one of the US’ oldest and, at the time, most well-regarded community theatres. After working, among other things, as a welder, he served as an aviation metalsmith in the US navy during WWII, after which he relocated to Hollywood, where he found work as a set builder and theatre director, and also acted on stage.

There is not much information on Hanna online, and his memoirs are an almost unreadable mess of anecdotes, mainly about his childhood and every single star he brushed shoulders with in Hollywood. After leafing through it I still can’t tell how Hanna got into movie acting or screenwriting. However, he did act in small bit-parts, mostly uncredited, in a good dozen movies between 1951 and 1954, before finding more success as a screenwriter. Between 1955 and 1958 Hanna wrote half a dozen films for AIP, most of them with Charles Griffith. However, The Amazing Colossal Man (1958) was co-written with director Bert I. Gordon and author/screenwriter George Worthing Yates. A commercial success, it was his second-to-last script for AIP. However, shortly after, his friend Jacques Marquette commissioned Hanna to write a very unofficial sequel of sorts to that film for Allied Artists — but about a giant woman. The result was Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, the movie which has become Hanna’s most lasting legacy. He had a small critical success with Raymie (1960), which won a prize at the Munich Children’s Film Festival. His credits become sporadic after 1961, with the decline of the classic B-movie, although he did still write a few low-budget films in the 70’s and 80’s. His last credit was the straight-to-video movie Star Portal (1997), which used the central premise of Not of This Earth. Hanna is credited for his original story.

Allison Hayes was born in 1930 in West Virginia and started partaking in beauty pageants, leading to her representing Washington in the 1949 Miss America contest. Her participation gave her a chance to work in local TV in Washington, which eventually opened the doors for Hollywood, where she was signed to a contract with Universal in 1954. However, despite appearing to her advantage in a couple of supporting roles, Universal terminated Hayes’ contract when she sued the studio for workplace injuries sustained during filming, including broken ribs. She the relocated to Columbia, where she appeared in the crime drama Chicago Syndicate (1955), she she later described as her best role. However, most of the press around the film focused on young Joanne Woodward, leaving Hayes in the shadow.

Hayes’ contract with Columbia also came to a quick end, and she found herself freelancing. In 1956 she was cast by Roger Corman at American International Pictures in the western Gunslinger, leading to a string of appearances in horror and science fiction B-movies, which is what Hayes is remembered for today: The Undead (1957), Zombies of Mora Tau (1957), The Unearthly, (1957, review) and The Disembodied (1957). This culminated in 1958 with Attack of the 50 Foot Woman for Allied Artists, in which she not only played the titular menace, but gave audiences proof of her dramatic abilities in the role as the neclected, alcoholic millionaire wife of philandering golddigger husband William Hudson. As opposed to many other struggling actors in Hollywood, Hayes didn’t seem to mind being typecast in horror and science fiction movies. However, it did hurt her career, insasmuch as studios were wary of casting actors from “juvenile” genre pictures in serious dramas. Hayes struggled on in independently produced westerns and crime dramas and increasingly tilted towards TV during the late 50s and early 60s. Among her films were also two more horror movies, The Hypnotic Eye (1960) for Allied Artists and The Crawling Hand (1963), directed by low-budget specialist Herbert Strock.

In a tragic turn of events, Hayes started experiencing severe, unexplained health issues in her early thirties in the 60s. She began to have difficultues walking without a cane, and experienced severe pain, which affected her usually good-natured mood, and caused her to drink heavily. Her last film appearence was the Elvis Presley comedy Tickle Me (1965), and she appeared in a couple of TV shows, but her work dried up in 1967. Eventually, Hayes read up on her symptoms and found that they were similar to those exhibited by certain factory workers. After consulting a toxicologist, she discovered she was suffering from lead poisoning as a result of eating a dietary supplement prescribed by her doctor. Hayes started a campaign which led to the supplement being banned from sale in the US. However, her health continued to decline, and in 1975 she was diagnosed with leukimia, and passed away two years later, only 46 years old.

William Hudson, playing Hayes’ cheating husband, is another recognisable face for SF enthusiasts. Hudson had an unremarkable career as a bit-part player in the 40’s before entering TV in the 50’s. He gained some recognition with recurring roles in the popular TV shows Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954) and I Led 3 Lives (1954-1955), the latter a spy show starring SF legend Richard Carlson. He continued to combine small parts in movies with guest spots in TV shows up until the early 70s, but it was science fiction that gave him his biggest parts. He played the lead in The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957, review), and co-leads in The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and its semi-sequel Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). He also appeared in small roles in two family comedies about astronauts: Moon Pilot (1962) and The Reluctant Astronaut (1967), the latter starring Leslie Nielsen, long before his comedy career proper.

Yvette Vickers is another actress almost exclusively remembered for her work with late 50s genre B-movies. Born in 1928, Vickers studied journalism but switched to drama and started appearing in TV ads and working as a model in the 40s. She had an uncredited part as an extra in Sunset Boulevard (1950), and did some TV work in the early-mid 50s, supplementing her work on stage and as a model. She got her breakthrough in AIP’s teen movie Reform School Girl, although in a supporting part – the lead was played by another SF favourite, Gloria Castillo.

Vickers immediately raised eyebrows with her steamy sensuality, and her bad girl image got her typecast in juvenile delinquency films and crime dramas, such as James Cagney’s directorial debut Short Cut to Hell, and William Witney’s Juvenile Jungle. She is probably best remembered for her memorable turns in AIP’s science fiction movies Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) and The Leech Woman (1959), the latter which provided Vickers with her only lead. She took advantage of her reputation as a sex kitten by appearing as a centerfold in Playboy magazine in 1959, and also posed for several other men’s magazines. However, her acting career, which had never reached giddy heights in the first place, started to decline, and by the early 60s, she appeared mostly on TV and in bit-parts in movies. She left the movie business in 1963, although she did sporadically turn up in films in the 70s.

During her latter years, Vickers became a fixture on fan conventions, with the resurge in interest in the old SF, horror and western movies thanks to home video. Described as a bubbly personality with lots of stories to tell, according to film historian Tom Weaver, who interviewed her, she made something of a living out of touring the convention circuit. According to a Los Angeles Magazine article, Weaver said: “These places pay all your expenses, meals, and maybe throw in a few dollars […] You can make some money autographing pictures for $20 apiece.” However, the low-budget “scream queen” only made international headlines much larger than her modest movie career would have made allowance for with her death. In the spring of 2011 a worried neighbour discovered Vickers‘ mummified body in the former actress’ dilapitated Beverly Hills house. Towards the end of her life, Vickers had suffered from mental health issues, started hoarding and secluded herself in her home, convinced someone was stalking her, and that “they” were out to get her. She had broke all contact with family and friends, and nobody had realised she had been dead in her home for over half a year.

Yvette Vickers was a much better actress than her patchy movie record would suggest. Perhaps she was simply too hot to handle for mainstream movie producers – and her early involvment in TV and B science fiction movies certainly didn’t help matters. That she was still beloved by B movie fans all over the world when she died was proved by her overstuffed mailbox with moulding fan letters – which was precisely what alerted her neighbour to her situation.

The rest of the cast is made up of B movie and TV bit-part actors, such as AIP regular Ken Terrell and stalwart Roy Gordon. Best known is probably German expat Otto Waldis, who specialised in playing benignt German scientists in such movies as Unknown World (1951, review) and Night the World Exploded (1957, review). He also played a rare Nazi villain in William Cameron Menzies’ ill-fated but intriguing speculative SF thriller The Whip Hand (1951, review).

Ronald Stein delivers, as usual, a strong score. While AIP skimped on almost all other costs, the studio, surprisingly, saw to it to have original scores for most of their films, as opposed to using stock music. AIP’s go-to composer was Ronald Stein. Stein taught music and composition at the California State University, and later in Colorado. He came to Hollywood after graduating, very much like Roger Corman, with no background in film, but a passion for working in the industry, and was immediately hired by Nicholson and Arkoff — for a very little pay, but steady work. His music elevated many otherwise questionable films, and his scores for films like Roger Corman’s The Haunted Palace (1963), Jack Hill’s Spider Baby or, the Maddest Story Ever Told (1967) and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rain People (1969) have been noted as particularly noteworthy.

Fans of Stein’s cite his premature death of cancer in 1988 as the reason he never got the recognition he deserved — that after his strong score for The Rain People, he was bound to go on to do bigger and better things. But the truth is that for 19 years between The Rain People and his sudden death, he did little worthy of note in film music, except a handful of super-low-budget films and a porno. His SF scores include: The Phantom from 10,000 Leagues (1955, review), Day the World Ended (1955, review), It Conquered the World (1956, review), Not of This Earth (1957, review), Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957, review), Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review), Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), Battle Beyond the Stars, Dinosaurus! (1960), Last Woman on Earth (1960), The Underwater City (1962), Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965), Queen of Blood, Zontar: The Thing from Venus, Creature of Destruiction (1968), and Frankenstein’s Great Aunt Tilly (1984).

Janne Wass

Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. 1958, USA. Directed by Nathan Juran. Written by Mark Hanna. Starring: Allison Hayes, William Hudson, Yvette Vickers, Roy Gordon, George Douglas, Frank Chase, Otto Waldis, Ken Terrell, Eileen Stevens, Michael Ross. Music: Ronald Stein. Cinematography: Jacques Marquette. Editing: Edward Mann. Makeup: Carlie Taylor. Sound: Philip Mitchell. Produced by Bernard Woolner for Woolner Brothers Pictures & American International Pictures.

Leave a comment