(4/10) The fourth film about the most prolific female mainstream movie monster of all time — Alraune — was the first one in sound. Movie star Brigitte Helm reprised her role as the artificially created man-eater in this German 1930 production. Director Richard Oswald tried to modernise the tale, but the result is a surprisingly uninspired potboiler.

Alraune. 1930, Germany. Directed by Richard Oswald. Written by Charlie Roellinghoff, Richard Weisbach. Based on novel by Hanns Heinrich Ewers. Starring: Brigitte Helm, Albert Bassermann, Harald Paulsen, Martin Kosleck, Käthe Haack, Ivan Koval-Samborsky. Produced by Richard Oswald and Erich Pommer. IMDb Score: 6.0. Tomatometer: N/A. Metascore: N/A.

The fourth, but not final, film featuring one of the most popular movie monsters of the early decades of cinema — Alraune — was made in the monster’s home country of Germany in 1930. This was the first version in sound and the second starring movie legend Brigitte Helm. Helm had previously starred in another Alraune film in 1928 (review), but despite this, the 1930 movie wasn’t a sequel, but a remake.

First things first: What’s an Alraune? An Alraune is one of four iconic monsters that got their cinematic birth in the Central European film scene that incorporated Denmark, Germany, Austria and Hungary in the span of seven years, between 1915 and 1922, during the heyday of German expressionism. These four monsters were: The Golem (1915), Homunculus (1916, review), Alraune (1918, 1919, review) and Dracula (1921, 1922).

The Golem, based on an old Jewish folk tale, was the creation of writer-directors Henrik Galeen and Paul Wegener, and went on to have three adventures in the films The Golem (1915), The Golem and the Dancing Girl (1917) and The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920). While never as iconic as Dracula or the Frankenstein monster, the Golem has continued to pop up here and there for the last hundred years. Dracula was first alluded to in the Austro-Hungarian film Drakula halala (1921), or “The Death of Dracula”, reportedly co-written by Michael Curtiz. The first actual (if unauthorised) adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel was, of course, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), again co-written by Henrik Galeen. Despite the enormous success of the 1916 film serial Homunculus (review), the title character didn’t really go anywhere — perhaps because there was too much of a resemblance to the Frankenstein monster: a giant artificial man looking for love and purpose in a world that fears and rejects him. There are interesting parallels to Alraune, though, as both she and Homunculus are explicitly described as having been “born” without a soul, and thus cannot understand the difference between good and evil, nor the concepts of love, friendship or empathy. Alraune had a longer span of popularity, but she too fell out of favour as the idea of artificial insemination became uncontroversial.

Alraune’s roots (pardon the pun) lie in the 1911 novel by the same name, written by German author Hanns Heinrich Ewers. Alraune is the German word for the mandragora plant, or mandrake in English. The mandrake root has long been used for various medical purposes, from pain alleviation to treating colic, insomnia and even infertility. It is mildly poisonous and hallucinogenic, and can irritate the bowel, causing all sorts of unpleasant side-effects. There’s also a long history of wives’ tales and myths surrounding the mandrake. Partly this is due to the looks of the root – it often resembles a small person, or homunculus. One legend states the the mandrake produces a deadly scream when pulled out of the ground. Another that when men are hung to die, they get an erection, and the ejaculated seed that drips into the ground gives birth to the mandrake root. The legend further states that women who copulate with these mandrake roots give birth to women without souls – empty and evil vessels. This is the legend that Ewers utilises in his book. But instead of using the alraune itself, he has his scientist collect the semen of a hanged man, and artificially inseminates a prostitute with it. The result is a woman who does not understand the concept of love and has a life filled with perverse relationships. She is adopted by the scientist, but when she learns about her unnatural origins, she takes her revenge on her maker – this is basically a variation of the Frankenstein theme.

The novel was published in 1911, 12 years after a Russian scientist had successfully artificially inseminated small animals. The concept caused moral outrage in conservative and religious circles in Europe (and America), and as a result the novel became a bestseller. Film critic Richard Scheib at Moria writes that “Alraune is essentially a position paper about the idea of artificial insemination. […] As such, Alraune enters into the debate on the subject with the wild alarmism of a tabloid headline. It is also hard not to see in some of this the embryo of the Nazi take on blood and genetics – with the idea that some people are just rotten, evil and socially inferior according to genetic predestination.”

The idea of artificial insemination was, naturally, an abomination from a conservatively Christian point of view, that one could (or should) create life without the holy union of man and woman was blasphemy. But for patriarchy it was also a highly alarming prospect: it suddenly gave women a potential liberation from the shackles of sexual tradition — in essence it meant that men were no longer needed for the species to survive — only their semen. And if women were freed from these shackles, it also meant a revolution for female sexuality: women could now finally be masters of their own bodies and urges.

This notion naturally tied in with another strong current in society: women’s liberation and women’s rights. This wasn’t only about sexual liberation, but political and economical as well. And one gets a feeling that Ewers didn’t like any of it. So, in his novel, the offspring of a hanged murderer and a prostitute is his ultimate nightmare: a woman who likes to have sex, has it with whom she herself wants and doesn’t apologise for it. Gasp! This woman, liberated from religious, patriarchal and moral norms he paints as soulless, heartless and forever doomed to unhappiness. When Alraune finally learns of her unnatural origins, she avenges herself upon her creator.

Around the time the novel was written there were also other factors involved that left their mark on Ewers’ novel. The idea of social Darwinism was making headway, and questions of human evolution interested scientists and science fiction writers alike. At the same time psychology as a science was slowly starting to form, with Jung and Freud establishing themselves as stars in the field. The question of the hereditary vs the learned, or nature vs nurture, was hot stuff. It was this question that, in the novel, was the starting point for Professor ten Brinken. ten Brinken wanted to prove that from the seed of a hanged murderer and the egg of a prostitute, he could raise an impeccably moral lady.

David Cairns at Mubi writes that “Ewers was an odd character, a devoted nationalist with a fancy for homosexuality and sado-masochism that insinuates tendrils of perversity into all his work. Despite believing Jews made the best Germans, he also got into bed with the Nazis, writing a screenplay about unsavoury martyr Horst Wessel, but by 1945 he had been branded an “un-person”; expunged from the records; forgotten to death.” Ewers also penned the script for the “creaky but influential” 1913 film The Student of Prague, generally considered the starting point for both the horror film genre and German expressionism.

Which brings us to the film at hand, the 1930 sound version of Alraune. While it may seem odd that such a successful film as Alraune from 1928 should get a remake only two years later, this was the case with many big films from the silent era. From a studio’s point of view, this was smart business: take a story you knew that the audience was already invested in, and present it with the novelty of sound. While the production company was new, as well as all the other actors, director Richard Oswald insisted on re-casting Brigitte Helm as Alraune. In a way, there really wasn’t any other choice. After her tremendous breakthrough in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927, review), she was Germany’s biggest movie star, and inhabited the role of the supernatural femme fatale after her turn as Alraune in 1928. Plus, she was a certain box office draw.

Like the 1928 film, this one follows the basic premise of the novel: The scientist ten Brinken creates a woman through artificial insemination, who turns out to be an immoral seductress who drives men to their doom. The scientist takes her in as his “daughter” or niece, but as she matures into her late teens, he too develops a sexual desire for her, while she, for the first time in her life, apparently, falls truly in love with another man. When confronted with her unnatural origins, she takes her revenge on her maker.

Still, the 1930 film is different from Galeen’s and Wegener’s version in a number of ways. Firstly, it sticks closer to the source novel, as it re-introduces the fact that Professor ten Brinken created Alraune in order to capitalise economically on her. But it also updates the main story for Berlin in 1930, whereas the earlier version still rummaged about in a pre-WWI gothic environment. This change shifts the emphasis from magic and superstition to science and social codes. There’s also a marked difference in that the earlier film had a prologue that showed Alraune as a child, exhibiting a clear sadistic streak, enjoying hurting animals. This notion is removed from Oswald’s version, in which there seems to exist no ill will from Alraune’s part toward the men that fall under her spell. Instead she seems to, in a way, be the victim of her own uncontrollable sexual and adventurous urges — a lack of inhibition and an uncanny power over men, who seem to be willing to walk into death in order to please her — which they also do. One man drowns when trying to fetch her flowers, another in a car accident when she urges him to drive ever faster.

This is a bit of a spoiler, but in the earlier film version Alraune is “redeemed” after having found true love, and understood that a woman’s place is beneath her man and not at his side as an equal: a hopelessly stuffy conclusion, much in line with the original novel. Oswald’s film, however, makes it clear that Alraune acts the way she does not because of some selfish misunderstanding of a woman’s place in society, nor out of her own volition, but rather because she was “born this way”. One can argue that Oswald’s script isn’t necessarily less stuffy, as it still posits that an emancipated woman is a threat to society. But Oswald also opens for the possibility that it isn’t actually Alraune that is at fault, but rather society, partly for creating her, but also for not being able to accommodate a modern woman with a will of her own. One should remember that this was the age of the flapper and there was a lot of movement toward greater equality in society. Still, the story being what it is, it can’t have the cake and eat it, so either Alraune has to change or meet a cruel fate, as all movie monsters ultimately do. Oswald chooses to honour her Frankensteinean roots, as she, and again, this is a spoiler, chooses to drown herself in order to save the man she loves from the curse that has been laid upon her by her creator.

Richard Oswald isn’t credited as screenwriter, but as the very personal filmmaker that he is, one can still surmise that the over-arching changes in the story come from his pen. This notion is further strengthened by the fact that none of the two credited screenwriters, Charlie Roellinghoff and Richard Weissbach, have any experience with this kind of film. Both were fairly new to script-writing, and mainly worked on comedies. Roellinghoff is the better known of the two, as he was also a fairly successful author, and worked on around 40 films in his career. During the silent era he mostly penned the title cards, rather than the overall screenplay, and one imagines that the two were brought in mainly to work on the dialogue and not the story itself.

While largely forgotten today, Austrian writer-director Richard Oswald was one of the pioneers of the German horror film and expressionism. His background was in theatre, but he was bit by the cinema bug in 1914 and didn’t look back. With his Sherlock Holmes productions and tales of mystery and the supernatural, movies like The Hound of Baskerville (1914), The Eerie House (1916), The Picture of Dorian Gray (1917) and A Night of Horror (1917) laid the foundation of the horror film. His best known movie is probably the classic Unheimliche Geschichten (Eerie Tales, or Uncanny Stories, 1919), a five-part horror anthology that served as a blueprint for the horror genre, based on five stories, by Robert Louis Stevenson, Edgar Allan Poe, and others. In 1916 he directed the sci-fi horror film Tales of Hoffmann (review), also covered at Scifist.

In 1925 Oswald co-founded the movie company NERO, and became one of the most important movie producers in Weimar Germany, backing some of the greatest films of the era, like G.W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918 (1929) and Pandora’s Box (1930), as well as Fritz Lang’s M (1931) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933). With the rise of Nazi Germany, Jewish Oswald quickly emigrated, first via Austria to France and England and finally to the US. He only made a handful of films abroad, and passed away in 1963, when visiting Germany.

Richard Oswald was an extremely prolific director: between 1914 and 1934 he directed over 100 films, and wrote or produced almost a hundred more. As a director he has been criticised for favouring quantity over quality, and there is at least some truth in this: compared to his more renowned contemporaries, Oswald’s films rarely showed any great artistic merit. Unheimliche Geschichten is perhaps the exception to the rule: its innovative use of shadow and light, the dramatic make-up of the actors, and the facial close-ups of horror and despair did contribute greatly to the rise of the expressionistic horror film. It was greatly helped by the superb acting of horror legend Conrad Veidt, who one year later would become immortalised as the murderous somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, starred in the wonderful horror sci-fi film The Hands of Orlac (1924, review), and went on to a spectacular career both in Germany and Hollywood.

When Oswald is remembered today, it is mainly because of his so-called “educational films” in which he tried to shine light on social taboos such as prostitution, poverty and homosexuality. In all cases, he sided with the outcast rather than with the society which condemned them. Best known of these movies is the 1919 film Anders als die Anderen, or Different from the Others, a melodrama about a homosexual musician who falls in love with his protegé, but things turn ugly when he is blackmailed by a man who has seen the couple walk hand in hand. Despite its — at the time — sleazy subject matter, the film sought to normalise the audience’s view on homosexuality, and its sentiment is echoed by the final words of a doctor in the movie: “Respected ladies and gentlemen take heed. The time will come when such tragedies will be no more. For knowledge will conquer prejudice, truth will conquer lies, and love will triumph over hatred.” The role of the homosexual musician has been named as the first gay role written for the screen. It was played by Oswald favourite Conrad Veidt, just a few months before his star-making turn in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Seen in the light of Anders als Die Anderen or Oswald’s prostitution films, Alraune can be analysed from the perspective of gender theory or the concept of “the Other”, and has indeed been analysed thusly. I personally think there’s a certain danger of over-analysing when you ascribe post-modern theories to slapdash movie productions that were more interested in raking in a decent profit than making any grand statements, but taken with a grain of salt, such ruminations often open up for interesting readings that, while not always accurate in the case of specific films, can be revealing when observing trends in film and culture history. For those interested in reading more, I can recommend O. Ashkenazi’s book Weimar Cinema and Modern Jewish Identity and Anjeana K. Hans’ work Gender and the Uncanny in the Silent Films of the Weimar Republic.

Alraune was apparently well-received by both audiences and critics, and was released in the US in 1934, where the New York Times‘ Mordaunt Hall gave it a favourable review, especially praising Brigitte Helm’s performance, as well as that of Albert Bassermann, playing Professor ten Brinken.

While Richard Oswald was influential for the emergence of German expressionism, he was never really an adherent of the style himself, with the exception of his interest in the uncanny and the psychological. Visually he eschewed the surrealism of the expressionism, but did set the template for the dramatic juxtaposition between light and shade that became so synonymous with the genre. The lighting is really also the only thing in the 1930 version of Alraune that echoes the fading expressionism, and that was always Oswald’s forte. The updated setting in modern Germany also called for a greater realism, both visually and to the script itself. While it’s a fresh and perhaps socially more interesting take on the story, it also makes it a bit duller. Online critic Mark David Welsh feels that the changes were “rather unfortunate as it robs the film of the nuances of the earlier version, making for a much more conventional picture.”.

To be fair, I wasn’t a big fan of the 1928 film to begin with, as I thought it misogynist and rather clunky. And I hated the socially regressive cop-out ending. However, I really liked Wegener’s performance and that of Helm, which I preferred to the modernised version, that removes the air of mystique around Alraune. And like Welsh, I preferred the story told through the operatic horror style, as it is more forgiving of muddled or non-existent character motivations and logic. The more expressionistic framing also provided better immersion through the eerie atmosphere. And Helm as an evil seductress was more effective than Helm as a — whatever she is supposed to me in the later version. Sexual deviant? Flapper on stereoids? Emancipated woman gone astray? I can appreciate what Oswald was trying to do with the story, but the problem is that he tries to take a progressive left turn, without really managing to break free from the source material. The Frankenstein connection is obvious, but there’s a radical difference. Frankenstein was a highly intelligent feminist novel. Alraune was an inane anti-feminist pamphlet. I’m not sure exactly what Oswald was thinking when he imagined he could turn the story into something actually progressive. The whole premise of the story is reactionary.

But regardless of my personal notions of the content of the film, it might still have worked as an effective film, if well made. Unfortunately Alraune is all over the place. As always with Oswald, there are moments of brilliance and facepalm moments. The lighting, as usual, is beautiful. Some scenes are well filmed. The rapidly edited car-race-as-orgasm scene is clever, even though I feel there was something of an over-abundance of rapidly edited driving scenes in the late twenties, partly thanks to the Soviet montage theorists. The final scene of the movie is achingly beautiful and haunting.

The Marquis de Suave at the blog Teenage Frankenstein writes that “The film is atmospheric if a bit creeky and awkward, benefiting from acting more restrained than typically found in early sound cinema.” In fact, the acting is a bit too understated for my taste, given the absurd operatic quality of the material at hand. I feel Helm is under-used in the movie, and to be honest, I don’t really see why Albert Bassermann received such high praise for his work on this film, as he comes off as rather bland compared to Wegener. Harald Paulsen as the romantic lead is sympathetic, but ultimately just along for the ride.

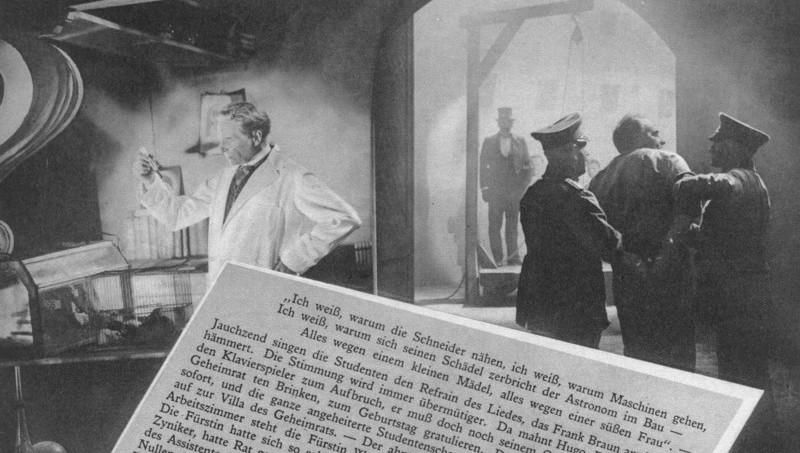

What is utterly clear from the movie is that Oswald was struggling with the new medium of sound. While there are scenes here and there that are brilliantly filmed and edited, for the most part Oswald uses extremely long takes with a single, static camera, tilting and panning as the actors move through the scene. At times this almost gives the impression of a filmed stage play. It’s as if Oswald wasn’t comfortable with editing sound, and preferred to get an entire dialogue in a single take. There’s also an awful lot of awkward shots of actors talking into flower pots, so to speak, and in wide shots the sound often has a hollow echo. And like many early sound films, the movie contains singing, as if directors thought that just because films now had sound, there had to be singing in them, even if it was completely out of tune with the story. Many of the actors, especially Bassermann, declare their lines as if they were standing on a theatre stage and had to reach the last aisle. Unfortunately this sort of declaring style highlights the absurdity of the lines, and makes the whole thing seem more like community theatre than the Royal Shakespeare Company.

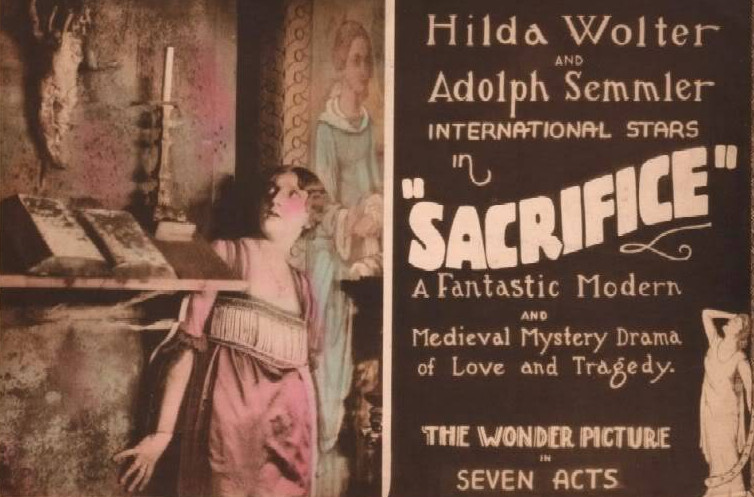

As stated, there had been three Alraune adaptations before this one, two of which are either lost or not accessible for home viewing. To read more about these movies, head over to my article on Alraune I & II. To be quite fair, the first Alraune film, the German Alraune, die Henkerstochter, genannt die rote Hanne (or Sacrifice, 1918), was not really based on Ewers’ book. Alraune was a bestselling book with a lurid reputation, so sticking the root in a title was a great way to get publicity. Sacrifice is more of a ghost story about a woman in present-day (1918) Germany whose child falls ill, and she is visited by the ghost of her ancestor, a witch, who shows her that the story of her life is repeating itself. Sacrifice isn’t lost, however, but a (nearly) intact 16 mm print has survived at the Eastman Kodak archives, and has been occasionally screened.

The second version of Alraune has been the focus of much debate. Conventional wisdom has it that this was one of the last Hungarian films directed by Michael Curtiz (Mihaly Kertész), best know, of course, for directing Hollywood blockbusters like Casablanca (1942). There’s been some confusion over whether Curtiz did in fact direct the movie, and whether there was a third Alraune film in the works for 1918 or 1919. This, in part, is due to some errors in an article in the Hungarian film journal Kepes Mozivilag in 1918, which gave the role of Alraune to the wrong actress. The film named the better known Margit Lux as the lead actress, when it was in fact cabaret performer Rozsi Szöllösi who played Alraune. The second credited director was a man named called Edmund Fritz in some advertising material, but is also credited as Fritz Ödön by other sources. However, Edmund Fritz is the germanised version of the Hungarian name Fritz Ödön. Ödön was in fact not a movie director, but a cabaret manager in Budapest, and probably Rozsi Szöllösi’s boss, who wrangled his way into the picture when Curtiz wanted his protegé to play the lead. Curtiz did later make a name for himself for spotting talent in night clubs, Doris Day being the most famous example. No copy of the film has survived. But according to what we can glean from press clippings and the character roster, the film seems to have followed at least the broad outlines of Ewers’ book.

There was actually a third version of Alraune at least planned for release in 1919, called Alraune und der Golem. We know there was a script written by Richard Kühle, that combined Hanns Heinrich Ewers‘ novel with the short story Isabella of Egypt by Achim von Arnim — Kühle novelised his script in 1920. It was also naturally inspired by Paul Wegener’s hugely successful Golem films, the second of which had been released in 1917. Swedish actor and director Nils Chrisander was set to direct, and posters had been drawn up.. However, it seems that for one reason or the other, the project fell apart. It’s too bad, as it would in essence have been the first ever monster bash movie, as it combined two of Germany’s most popular movie monsters at the time, the Alraune and the Golem.

Alraune got a final remake, again in Germany, in 1952 (review), directed by Arthur Maria Rabenalt, and starring Hildegard Knef and Erich von Stroheim. By 1952 artificial insemination was a pretty standardised procedure, and so it was noted even by contemporary critics that the film was made 20 years too late. Variety noted that “in the early 1900s, when the H. H. Ewers novel Alraune cut a swatch in the Germ

an-language world […] the very thought of artificial insemination of humans was mentionable only in whispers.” and that “times and sensations change.” Modern critics concur, calling the film drab and archaic. David Cairns at MUBI has explicit problems with the female lead: “A strange nymph like Helm was perfect for this twisted yarn, but the 1952 version suicidally casts a big, rangy, emphatic woman who radiates sturdiness and good health. And she would have to be called Hildegard Kneff (sic), a name with the allure of a hockey puck.”

Science and changing public perception of artificial insemination (thankfully) made any remakes of Alraune impossible, but the male uneasiness over assertive and sexually independent women didn’t disappear anywhere. The dominatrix and the fembot, not to mention alien women from matriarchal societies became staples in science fiction. Oh all the lurid possibilities that the filmmakers didn’t even need to allude to in the British film The Perfect Woman (1949, review), where a scientist builds a mechanical wife for his friend (modelled on his daughter, no less). And in the fifties there were the spider women of Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review), the Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), and of course the leather-clad sexual fantasy of the Devil Girl from Mars (1954, review), and that’s just picking a few off the top.

In the 1995 film Species scientists splice human and alien DNA, resulting in a very often nude Natasha Henstridge who also matures rapidly, has an obsession with sex and seems to have no qualms about killing men by piercing their skulls with her tongue. So much an impact did Miss Henstridge have on my generation of adolescent boys, that the film spawned two very inferior sequels. The original story was also made into an updated Russian series in 2010. In later years with all discussion on artificial intelligence, stem cells and cloning, artificially made babes with questionable morals have of course become a staple of sci-fi – the many incarnations of Milla Jovovich in Resident Evil and the Alien-Ripley in Alien IV being among the more famous ones.

German expressionist films in the 1910s and 1920s had a profound impact on cinema in general and on horror and sci-fi in particular. Films like The Golem and Nosferatu set the tone for Universal’s horror franchise in the 1930s. Alraune inevitably feels like the forgotten little sister, who was never invited to play tag. There are probably several reasons for this, and it would be too easy to chalk it up to simple misogyny or discrimination. One reason, of course, is that Alraune never was as visually iconic as the other famous monsters. Nosferatu, the Golem, Frankenstein’s creature and Mr. Hyde were all instantly recognisable. But Alraune’s monsterism wasn’t external, but internal. And alluring though Brigitte Helm was in her Alraune films, her portrayals of the artificial woman were mere shadows of her mesmerising performance in Metropolis. Influential though they were, Henrik Galeen and Richard Oswald were no Fritz Lang, and nobody was ever able to coax that same magic out of Helm that he once did. And to be fair, even the best remembered version of the Alraune films, the 1928 adaptation, is generally considered to be an uneven and ultimately rather dull affair, relying more on its lurid subtext than its actual content.

However problematic the character is from a feminist point of view, it is also in some sense a shame that nothing more became of the silver screen’s first female horror icon — and in fact the most prolific female movie monster. Alraune is the only female horror spawn to carry her own mainstream franchise in a total of five films over nearly four decades.

The 1930 entry into this franchise updated Alraune to the sound picture — rather clumsily, but still. As stated, neither the 1928 nor the 1930 versions are any masterpieces, and it may be a question of personal taste which one you prefer.

The legendary femme fatale Brigitte Helm, was only 18 when she began filming Metropolis with demon director Fritz Lang, and her only film experience at that time was a screen test for Lang’s epic Die Nibelungen. Metropolis turned her into one of the world’s biggest movie stars, and she was typecast as the femme fatale. After Metropolis she, perhaps unwisely, signed 10 year contract with Ufa, and more or less had to play whatever they placed her in, thus: vamps and more vamps. After a while she grew so frustrated with playing nothing but the same roles, that she actually took the company to court in 1929, trying to get out of her contract, but to no avail. She lost the trial, and most of her salary after that went to paying off the court debts. Her 29 films were a roller-coaster of bad and brilliant movies – notable are The Love of Jeanne Ney (1927), where she plays a blind woman, Crisis (1928), where she portrays a spoilt woman of the world who from sheer boredom almost destroys her own life, and L’Atlantide, where she plays a an opaque, otherworldly goddess driving men crazy. She was considered for the title role of James Whale’s masterpiece Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review) before Elsa Lanchester was cast. Before she quit acting she appeared in yet another sci-fi film, the today largely forgotten classic Gold (1934), where she got to play an unusually well-balanced character.

Albert Bassermann, playing professor ten Brinken, was one of Germany’s biggest stars of both the stage and film, often playing men of authority or historical profiles, such as Columbus or the Pope. He fled the Nazis via France to Hollywood, where he almost immediately landed a role in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, which earned him an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor. Bassermann remained a popular character actor in the US until his retirement in 1948. He appeared in the WWII propaganda film Invisible Agent (1942, review), another one in a long line of inferior sequels to James Whale’s The Invisible Man (1933, review).

Harald Paulsen, the romantic lead, was also a popular stage performer, who made a successful transition to film, and became something of a matinée idol in the twenties. He is best remembered for his performance in Bertolt Brecht’s original stage production of The Threepenny Opera, where he played The Dapper, popularly known as Mack the Knife. His original recording of the classic song can be hear here. He also appeared in Robert Wiene’s flopped follow-up to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Genuine (1920). Despite his early recognition as a Brecht devotee, Paulsen later proved to be a full-fledged Nazi, proudly wearing the Swastika and denouncing his colleagues for not being devoted to the cause. He appeared in a number of propaganda and hate films during the Nazi rule. After a three-year blacklisting after the war, he returned to film acting in 1948, but for natural reasons had difficulty recapturing his former fame. His son Uwe Paulsen was a well-known voice actor, best known for dubbing Martin Shaw in the British crime series The Professionals (1981-1991), and for his work dubbing Christopher Walken.

For those who follow this blog with avid interest, there are a couple of familiar names among the cast. In the role of the ten Brinken housekeeper, Frau Raspe, was cast Käthe Haack, whom sci-fi fans may remember as Magda, daughter of the deluded industry tycoon Herne, the protagonist/antagonist of the German dystopian epic Algol (1920, review). Haack was a petite blonde beauty who had a film and TV career that spanned an astounding 70 years. She started her career on stage as a teenager, and made her first film appearance in 1915, and her last TV appearance in 1985. Even though she remained true to the stage all of her life, she had the time to make over 250 film or TV appearances. Despite working in Germany through the war, Haack was able to avoid the most egregious propaganda films. In 1973 she was awarded a lifetime achievement award at the German Film Awards.

Frau Raspe’s husband, the family driver who falls prey to the lures of Alraune, is played by Ukrainian actor Ivan Koval-Samborsky. This stage actor established himself as a film fixture with the hugely successful 1925 science fiction action film serial Miss Mend (review), in which he had a central role as an unwitting accomplice to the film’s evil scientist, and the love interest of the movie’s titular heroine. He also had prominent roles in Vsevolod Pudovkin’s classic Mother (1926) and the celebrated urban comedy The Girl with the Hat Box (1927), starring Swedish-Ukrainian beauty Anna Sten. Koval-Samborsky teamed up with Sten again in Fyodor Otsep’s critically acclaimed The Yellow Ticket (1928), where he played the male lead. In 1928 he moved to Germany, where he had a good career during the last years of the silent era, doing big supporting roles and even a couple of leads. However, with the advent of sound, he found it harder to secure work in the German film industry because of his accent, and moved back to the Soviet Union in 1932, where he continued a decent film career until he was arrested — with his German exile as the reason, and sent to Kyrgyzstan, where he continued his work on stage with much success. In 1949 he became the director of the Grozny Lermontov Theatre in Chechnya. He made a comeback to the screen in 1957, and appeared in a dozen films before his death in 1962.

Martin Kosleck has another prominent role as a young man who falls for the allure of Alraune. Kosleck was yet another stage-cum-film actor who fled to the US during the Nazi rule. Here he became a prominent film Nazi, appearing in a whole slew of WWII movies, including the afore-mentioned Foreign Correspondent, with Bassermann. After the war the demand for Nazi villains diminished and like so many other European actors he found himself working primarily in B-movies.

Horror aficionados may remember Kosleck from a string of Univeral cheapos from the mid-forties. He appeared in The Mummy’s Curse (1944) and The Frozen Ghost (1945) opposite Lon Chaney, Jr., who he is reported to have disliked intensely. His biggest role in the four Universal films came in House of Horrors (1946), and he also appeared in the better known She-Wolf of London (1946). Most iconic is perhaps his top-billed turn in the micro-budget cult classic The Flesh Eaters (1964), that’s been called the very first gore film (although this is debatable), where he plays (surprise, surprise) a mad Nazi scientist. Oddly enough he returned two years later in another film about bacteria devouring humans from the inside, the legendarily bad TV-pilot-turned-theatrical-film Agent for H.A.R.M. (1966), this time playing a Soviet villain. However, he made much of his income from the fifties onward doing guest spots on TV shows — he appeared in over 40 shows — including The Outer Limits, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Wild Wild West, Batman and Night Gallery. He made his last film appearance in 1980 in the campy comedy The Man with Bogart’s Face.

Cinematographer Günther Krampf also shot the sci-fi films The Hands of Orlac and The Tunnel (1935). He also shot the Boris Karloff horror film The Ghoul (1933) and worked as assistant cinematographer on Nosferatu. Music composer Bronislau Kaper won an Oscar for his work on Lili (1953), and was nominated for two more.

Janne Wass

Alraune. 1930, Germany. Directed by Richard Oswald. Written by Charlie Roellinghoff, Richard Weisbach. Based on novel by Hanns Heinrich Ewers. Starring: Brigitte Helm, Albert Bassermann, Harald Paulsen, Adolf E. Licho, Agnes Straub, Bernhard Goetzke, Martin Kosleck, Käthe Haack, Ivan Koval-Samborsky, Liselotte Schaak, Paul Westmeier, Henry Bender, Elsa Bassermann, Wilhelm Bendow. Music: Bronislau Kaper. Cinematography: Günther Krampf. Art direction: Otto Erdman et.al. Sound: Erich Leistner. Produced by Richard Oswald and Erich Pommer for Richard-Oswald-Produktion and Ufa.

Leave a comment