Radiation is once again to blame as giant grasshoppers devour Chicago in Bert I. Gordon’s 1957 cult classic. While inept in most departments, it boasts a decent cast and is a lot of fun to watch. 4/10

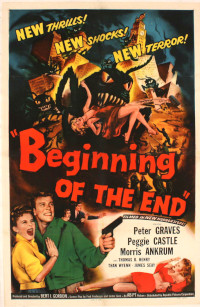

Beginning of the End. 1957, USA. Produced & directed by Bert I. Gordon. Written by Fred Freiberger, Lester Gorn. Starring: Peter Graves, Peggie Castle, Morris Ankrum, Than Wyenn, Thomas Browne Henry. IMDb: 3.9/10. Letterboxd: 2.6/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

The whole town of Ludlow, Illinois has been destroyed overnight, with all 150 residents missing. Driven photojournalist Audrey Aimes (Peggie Castle) is initially blackballed by the military, but soon gains their cooperation. Suspecting atomic causes, she visits the nearby government agricultural research station, where she meets entomologist Ed Wainwright (Peter Graves) who has been experimenting with radiation to grow enormous crops. Investigating a nearby grain storage, his colleague Frank (Than Wyenn) is attacked and eaten by a giant locust.

So begins the end, both of the world and of short-lived production company American Broadcasting Company-Paramount Theatres (AB-PT), the 1957 film produced and directed by the original Mr. BIG, Bert I. Gordon. Released on a double bill with Boris Petroff’s The Unearthly (review), the film was financially successful, although panned by critics.

Dr. Wainwright suspects that locusts have gotten into the research station and eaten the radioactively enhanced vegetables, and grown to enormous size. When the national guard investigate, they are swarmed by the giant insects and are forced to retreat. Wainwright and Aimes travel to Washington, where the military brass is initially reluctant to call in the army to squash a few bugs. However, after a timely phone call from Illinois, where it is reported that hundreds of locusts have broken through the national guard’s line of defense, General Hanson (Morris Ankrum) is put in charge of operation bug hunt.

Terrific battles ensue between the army, armed with fire bombs, tanks, bazookas and tanks of pesticide, and the grasshoppers, with the locusts emerging triumphant. Dr. Wainwright works around the clock to find a way to kill the creatures, but when they start swarming Chicago, Gen. Hanson gives him hours to come up with a solution before the army will order the final solution — dropping an atomic bomb on Chicago (after evacuation).

Finally, Wainwright comes up with a solution: imitating the mating call of the locusts and drive them out to sea, where they will drown. But for this, they need a live locust on which to experiment with sounds generated by an electric oscillator. They capture said beast, but now the clock is ticking: Wainwright and Aimes now have an hour and a half to find the tone that emulated the mating call, before the atom bomb drops on Chicago.

Background & Analysis

Beginning of the End was produced by the company AB-PT, which was born in 1953 with the merger of TV station ABC and the movie theatre chain United Paramount Theatres (the latter created in 1949, with the separation by US courts of movie studios and theatres). In 1956, AB-PT announced they were starting a movie production company, and signed a distribution deal with Republic Pictures. Beginning of the End was AB-PT’s first movie, and was set to be written, produced and directed by Bert I. Gordon, who had a background as a supervising TV producer, and had directed two low-budget SF monster movies. The choice of Gordon as producer and director clearly indicated AB-PT’s motivations: the company was setting itself up as a rival to American International Pictures, with the aim of producing dirt-cheap movies for the exploitable teen market. Later, the company president claimed that AIP’s movies had an average budget of $300,000, but this is hard to believe considering the output, unless the films had really big overhead costs. AIP made their films on a budget of around 100,000 dollars, and Beginning of the End looks like it was made on a similar budget — albeit with a larger cast.

While the story idea was undoubtedly Gordon’s own, the script ended up being written by Fred Freiberger and Lester Gorn. Freiberger was a seasoned screenwriter, and one of the writers of the classic The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review). Gorn was a book editor and columnist.

The script draws inspiration from two primary sources: the classic big bug movie Them! (1954, review) and H.G. Wells‘ novel The Food of the Gods and How it Came to Earth (1904), a story which Gordon later wound up adapting for film twice. Wells’ novel is both a satire and a socio-philosophical treatise on the subject of scale in society and social development. The first part of the book, which is the most famous, follows the developments of a new superfeed used for growing large chickens, which gets out into nature and starts transplanting itself through the food chain, creating monstrous wild animals. The film’s similarities to Them! are so obvious that they must be viewed as Gordon’s deliberate homage to the influential movie. For example, both films start with two police officers encountering a wrecked car/trailer and the line spoken by Graves from which the title is derived is almost a verbatim quote of one of Edmund Gwenn‘s lines in the earlier movie.

The plot development is also very similar: the protagonists follow in the footsteps of the havoc wreaked by the giant bugs, and try to convince a sceptic military of their findings. Finally, as the giant critters start moving in on a major city, the military gets on board with the scientists, and together they seek a way to destroy the menace, before the bugs threaten to multiply and take over the world. Swap out the giant bugs and replace it with a giant reptile, and you basically have the plot of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms — the movie which screenwriter Fred Freiberger also wrote, and which is considered the blueprint for all 50’s giant monster films to come.

There is a myth that all of the 50’s was jam-packed fith giant bug films, but the fact is that up until 1957, they were relatively rare. Them!, released in 1954 was really the first, and it was followed up by Tarantula (review) in 1955. But these two films, with relatively large budgets, didn’t spawn any immediate imitators — perhaps because of the challenges in creating realistic special effects. But in the beginning of 1957, Universal opened the flood gates with The Deadly Mantis (review), a low-budget film with varying special effects, which performed reasonably well at the box office. The five following years then saw a deluge of cheaply realised giant insects of various kinds drowning the silver screen.

The script of Beginning of the End has its pros and cons. It is as derivative as they come, has terrible dialogue and no rhyme or reason to either its logic nor scientific plausibility. Graves explains that “radiation induces photosynthesis”, and acts as a substitute for the sun during the night, allowing plants to grow to enormous sizes. No, that is not how either radiation nor plants work. Then of course the idea that by eating something that has been enlarged by “radiation-induced photosynthesis” an animal would itself start to grow, is naturally complete hokum. The film starts off strong with the introduction of Audrey Ames, painting a feminist picture of the fearless and stubborn female reporter, famous for her war reporting, who won’t take no for an answer. But halfway through the film, Ames all but disappears from the plot, and is reduced to a passive bystander. Also, why she, a journalist, is suddenly promoted to both senior strategist and scientist in a military operation involving possible bombings of US cities is unclear (not that it is any clearer why an entomologist is suddenly given what seems to be the position of commander in chief of the US military forces). On the other hand, the pace of the script is brisk and the story entertaining, with frequent changes of scenery in order to keep things interesting.

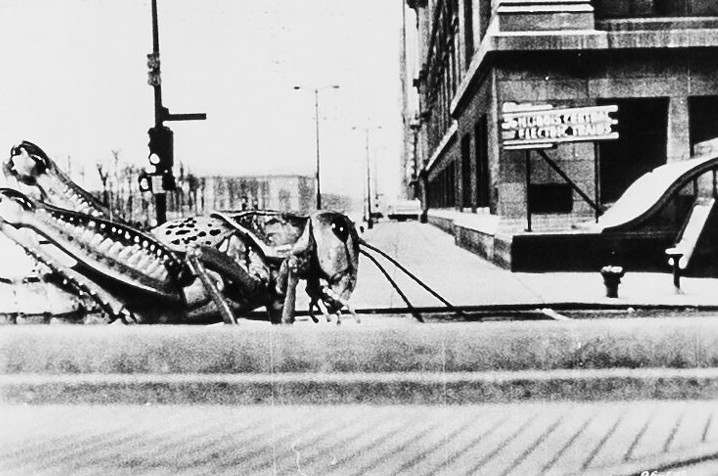

I first encountered Bert I. Gordon through his directorial debut, the deadly dull mess of a film which is King Dinosaur, in which a team of scientists stroll around a forest pretending to be the first team to explore a new planet, doing nothing but complaining about how boring all this “science stuff” is. Beginning of the End feels like it was directed by another director altogether. Here, Gordon directs at a brisk pace, although much of it may be down to the work of later Emmy-nominated editor Aaron Stell. The editing is most impressive in the scenes of battles between the locusts and the soldiers, and actually makes it feel as if there fas a frantic fight going on. Or really, we only see the skirmishes, as, for reasons explained below, Gordon only had 12 grasshoppers on hand, so he had to cut much of the intended footage of the locusts swarming Chicago. The battle scenes rely heavily on military stock footage edited together with live action and blown-up footage of grasshoppers, some of which is fuzzy and out of focus, other over-exposed, and often with clear matte lines.

The special effects, as is usual in Bert I. Gordon films, are sub-par, but somehow ingenious in their cheap crudeness. Gordon had initially considered animated grasshoppers, but the studio quickly decided this was too costly. Instead he opted for using live grasshoppers. He purchased 200 non-hopping, non-flying grasshoppers from Waco, Texas, which had recently seen an outbreak of exceptionally large locusts. Gordon chose them because they were the only readily available species large enough to hold camera focus. However, when crossing the border to California, all 200 insects had to be sexed by an entomologist, as Gordon was only allowed to bring males into the state, to prevent them from breeding. Unfortunately, no-one thought of feeding them in the interim, so the locusts began feeding on each other. When he finally arrived in Los Angeles, only 12 grasshoppers remained.

In order to incorporate the hoppers with live action footage, Gordon used several techniques, such as split screen, static mattes and rear projection. Most important, he had worked out a unique travelling matte technique that, according to Glenn Erickson, “combined images with a bi-pack method in a camera, rather than through expensive optical printing”. Erickson writes that the matted locusts are “such a mismatch that they look like cutouts pasted onto the screen, but Gordon clearly had the attitude that anybody complaining would first have to admit they bought a ticket to a picture about giant grasshoppers”. His most important time and cost-saving technique is perhaps the most ingenious in its low-budget simplicity: he simply ordered blow-up prints of photographies of buildings and streets and placed the grasshoppers on top of the photos, directing them with puffs of air. When one was supposed to fall off a building after being shot, Gordon simply tilted the photograph and blew the insect off the picture. The effect is obvious, as you see the flat shadows of the bugs against the paper, but you can sort of buy into it, at least until the grasshoppers start to walk across the sky. Gordon provided all the effects shots, literally working out of his own garage.

As was more often than not the case in 1950’s science fiction movies, atomic radiation is once again the villain in Beginning of the End. But while the films of the early 50’s often used the radiation trope to comment on geopolitical affairs, by the second half of the decade, the tropes had mostly been emptied of their ideological content. Now, radiation was just another piece of unobtanium, and giant monsters were just simply giant monsters. It is hard to find a political message in Beginning of the End. The film does tie in to the debate over the harmful effects of pesticides such as DDT, which was starting up in the US at this time, but again, it feels more like an opportunistic use of a thing that is a thing than any real attempt at social commentary.

The film begins better than it has any right to do. It is unusual for a 50’s SF movie to lead with an independent, capable and intriguing female character, and Peggie Castle does a good job of portraying the tough-as-nails, but sympathetic Audrey Ames. She cuts a smart figure when she rolls into the small town in her expensive white convertible, complete with car phone, and strolls out in a matching, stylish white dress. She immediately takes charge of the situation, and Graves’ Dr. Wainwright is really just tagging along. But as soon as the locusts enter the picture, the screenwriters do a 180 degree reversal on the relationship, and the movie sadly descends into every giant monster movie trope you can think of. And despite the fact that there is plenty of action in the film, you soon get tired of learning of major plot developments through newspaper headlines, telephone calls, after-the-fact dialogue or someone commenting off-screen. The finale is a major letdown. After all the build-up, the film simply ends with [spoiler!] the locusts walking over the edge of a photograph.

The acting is fine. Peter Graves always brings an air of naturalism and believability to even the most outrageous of premises. Peggie Castle is great in half the movie and a wallflower for the rest of it. Morris Ankrum is always a treat, if nothing else, then because he is like a warm blanket for 50’s SF fans. Even if the film is bad, you can always feel at home when Ankrum is on screen. The rest of the cast is all capable, with no special mention needed.

Beginning of the End has been described as Bert I. Gordon’s best movie. As I haven’t seen them all yet, I can’t verify that claim, but it certainly is better than King Dinosaur. The cast must be commended for taking a picture about giant grasshoppers devouring Chicago seriously. The movie never winks at the audience, but goes about its ludicrous business straight-faced. Nevertheless, to enjoy it, one must put on a gleeful face. If you get in the right mood, you can enjoy what does work, the snappy pacing competent editing, as well as the almost irrestable charm of Gordon’s DIY special effects.

Release & Reception

Beginning of the End premiered in July 1957, on a double bill with Boris Petroff’s The Unearthly. It was universally panned by critics, but still managed to make a decent profit. Mae Tinnee at the Chicago Post wrote: “The film obviously was made on a shoestring budget, and the people in it are no more than props for the magnified insects”. The Los Angeles Times critic thought the movie was so bad that it cheated the audience. D.M. at the Daily News (New York) called the film “preposterous”, and wrote that the special effects team was “woefully inadequate”.

Trade papers weren’t any more merciful. Variety said: “Summarizing the plot of Beginning of the End is like rehashing the story of several dozen similar films. […] Even taken on its own terms—as a low-budget exploitation feature—Beginning of the End hardly reflects the best effort of a major theatre circuit.” Harrison’s Reports called the film an “extremely ordinary and mediocre ‘carbon copy’ of numerous other similar pictures that are currently glutting the market. Little imagination has gone into the treatment given the weak script, which is further handicapped by poor direction and unbelievable characterizations.” However, the Motion Picture Exhibitor said: “Special effects are well done, and interest is maintained throughout”, leaving a reader wondering if the critic had actually seen the film.

Beginning of the End has a 3.9/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on over 2,700 votes and a 2.6/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on 1,000 votes. AllMovie gives it 3/5 stars, and TV Guide calls it “a ludicrous, cliche-filled movie”.

While no-one thinks this is a particularly good movie, several modern critics are at least forgiving. Richard Scheib at Moria writes in his 2/5 star review: “Nevertheless, most of these scenes work passably well for what was accepted back in the era. There are some not bad effects of the grasshoppers climbing the skyscrapers of Chicago, although in later shots it becomes clear that they are simply crawling across a photographic blow-up rather than models.” Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV says: “it’s very far from the worst film that Gordon was going to make in his career and at a fleet-footed 74 minutes it never outstays its welcome.” And according to Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant: “The upshot of all this is that Beginning of the End is so goofy and inept, it’s irresistable.

Cast & Crew

Bert I. Gordon started to make home movies at the age of nine, and then moved into commercials before making his first film in 1954. Gordon became famous for his cheap visual effects, which he created himself along with his wife Flora, thus cutting costs on his productions. Unfortunately Gordon didn’t quite have the talent, the time, the money, nor the equipment to make good travelling mattes, such as for example Universal used on their giant bug films. Instead he often used high-contrast superimpositions, which sort of functioned as a poor man’s travelling mattes, but left fuzzy edges and often turned whatever critter he was adding to the picture more or less transparent, sometimes with big holes in them where they reflected highlights. Another one of his favourite techniques was the age-old method of back projection, which, when done well, can work very effectively, stationary mattes and split-screen. Sometimes his effects came out quite nice, but more often than not they looked very cheap and amateurish.

Gordon often used his effects to portray gigantic critters or people, earning him the moniker “Mr. B.I.G.” (which of course was also an allusion to his initials), and is best known for films like The Amazing Colossal Man (1957, review), Attack of the Puppet People (1958, review), Earth vs. the Spider (1958, review), and his later, most successful film Empire of the Ants (1977), which was nominated as best picture at the first annual international fantasy film festival Fantasporto in Portugal in 1982. It lost to the Croatian movie The Redeemer. He became a prolific director for American International Pictures, churning out super-cheap sci-fi pictures in the late fifties, but left the company in 1960, working as an independent director/producer. Some of his later pictures did hold a slightly higher standard, but not all of them. But Gordon also branched out to other genres, like sword and sorcery, children’s movies, pirate films, witchcraft and horror films, a few murder thrillers and sexploitation movies. He kept on directing until the late eighties, although his films became less frequent, and then retired from the business after the movie Satan’s Princess (1989). He released an autobiography, and in an interview in 2015 said to have written a few screenplays. In 2011 he got a lifetime achievement award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films, which apparently prompted him to prove that he wasn’t quite dead yet. So in 2014, at 92 years old, he returned to the director’s chair after 26 years with the independently produced B horror film Secrets of a Psychopath, which had a limited theatrical release and was hardly noticed outside of genre circles. It received lukewarm reviews when it was released on DVD in 2015. Gorden passed away in March, 2023, at the very respectable age of 100.

The schlocky director has his defenders, such as Gary Westfahl, who on his Biographical Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Film states that although horribly flawed from an adult point of view, his films still had a huge impact on children when they were released. According to Westfahl, children could relate to the idea of being small in a world of giants, and, he posits, children didn’t understand enough to realise how dumb the dialogue and the plots of Gordon’s films were, neither did it matter to them that the effects were bad. Giant insects were inherently scary.

Westfahl also writes: ”Further, while his early films were usually threadbare – classic mom-and-pop operations, with Gordon and wife Flora Gordon chipping in for most of the offscreen labors – they were not slapdash; within the confines of his circumstances, Gordon usually tried to do good work, and if blessed with capable performers and a decent story, he might succeed. Only when Gordon attempted to cater to teenagers – an age group he manifestly did not understand – was an abysmal failure guaranteed.”

Lead actor Peter Graves received his first leading role in a science fiction movie just after making his Hollywood debut, that of the middle-aged scientist apparently picking up the words of Jesus Christ broadcasting from Mars in the anti-communist propaganda clunker Red Planet Mars (1952, review). He went on to star in Willie Wilder’s Killers from Space (1954, review), fighting googly-eyed aliens, It Conquered the World (1956, review), Beginning of the End (1957), The Clonus Horror (1979), and is perhaps best known to young(er) viewers as Captain Clarence Oveur in Airplane (1980) and Airplane II (1982), the second which included SF elements. He also appeared in a cameo as himself in Men in Black II (2002). In between his 50’s B-movies and his comedy fame, Graves found TV fame — first in the lead as Jim Newton in the family western Fury (1955-1960) and then in the role that would define his career, Jim Phelps in Mission: Impossible (1966-1973), and its revamp (1988-1990).

Graves was of Norwegian, English and German descent, born Peter Aurness in Minnesota in 1926. Graves was an old maternal family name. He changed his name partly so he would not be confused with his brother James Arness, known to SF fans as the Thing in the original The Thing from Another World (1951, review), and the rest of the world as the star of the long-running TV series Gunsmoke. From 1987 to 2001 Graves hosted the TV show Biography, which in 1997 received an Emmy for its episode on Judy Garland. He won a Golden Globe for his work in Mission: Impossible in 1966, and was nominated for a Globe in 1969 and 1970, and nominated for an Emmy in 1969. Peter Graves passed away in 2010.

Peggie Castle had a good career as a B movie leading actress and in TV. One of the many Hollywood starlets pegged for the movies more for their looks than for their talents, Castle did have a background in stage and radio work from her youth, and managed to keep working steady in decent roles for over a decade between 1950 and 1962, which was when she retired from acting, at just 35 years of age. Unfortunately she developed an alcohol addiction and passed away from cirrhosis in 1973. She appeared in the terrible red scare SF movie Invasion U.S.A. (1952, review) and Beginning of the End (1957).

Morris Ankrum was a constant presence in science fiction films from the 50’s as military men, scientist and other authority figures. Ankrum was especially memorable as the Martian leader Ikron in Flight to Mars (1951, review), as the colonel fighting aliens in Invaders from Mars (1953, review) and as the UFO-abducted general in Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956). All in all, he appeared in at least 15 SF movies.

Thomas Browne Henry, in a prominent role as a colonel, was another actor whom B-movie audiences were used to seeing dressed in army fatigues. Sometimes in SF movies like Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), Beginning of the End (1957), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review), The Brain from Planet Arous (1957, review), Space Master X-7 (1958, review) and How to Make a Monster (1958, review).

Among the bit-part actors are a number of interesting character. Blink and you’ll miss the original Superman, Kirk Alyn, as a B-52 pilot. Alyn was the first actor to portray Superman on screen in the 1948 serial Superman (review). There’s also a small part by the extremely prolific voice and character actor Paul Frees. Frees’ most prominent work was done in animated films and series, but because of his deep voice and strong delivery, he was often cast in live-action movies as radio reporters, newscasters, commentators and as a narrator. He is perhaps best known for his role as the narrator/radio reporter in The War of the Worlds (1953, review).

Dennis Moore was a prolific gunslinger in over 200 westerns serials, Poverty Row films and TV shows, and hit his career peak during WWII, when many of the stars of Hollywood were drafted into service. He played the lead in a number of serials, including the SF-ish The Purple Monster Strikes (1945). James Douglas got his spot in the sun in over 400 episodes as Steven Cord in the soap opera Peyton Place between 1965 and 1969. Lyle Latell had a small brush with fame in the recurring role as Pat Patton in a number of Dick Tracy films in the 40’s.

Janne Wass

Beginning of the End. 1957, USA. Directed by Bert I. Gordon. Written by Fred Freiberger, Lester Gorn. Starring: Peter Graves, Peggie Castle, Morris Ankrum, Than Wyenn, Thomas Browne Henry, James Seay, John Close, Kirk Alyn, Paul Frees. Music: Albert Glasser. Cinematography: Jack A. Marta. Editing: Aaron Stell. Art direction: Walter Keller. Makeup: Steve Drumm. Special effects: Bert & Flora Gordon. Produced by Bert I. Gordon for AB-PT Pictures Corp.

Leave a comment