The juices from a prehistoric fish turns a mild-mannered professor into a raging Neanderthal in Jack Arnold’s 1958 monster programmer. While a fairly entertaining low-budget romp, the film’s weak, contrived and repetitive script and sub-par special effects make it a low-point in Arnold’s career. 4/10

Monster on the Campus. 1958, USA. Directed by Jack Arnold. Written by David Duncan. Starring: Athur Franz, Joanna Moore, Troy Donahue, Nancy Walters, Eddie Parker. Produced by Joseph Gershenson. IMDb: 5.8/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Anthropology professor Donald Blake (Arthur Franz) is giddy as a school boy when he gets a delivery from Madagascar in the form of a recently deceased coelacanth fish – a so-called “living fossil”, which he intends to research and use in his lectures about evolution. But little does he know that the now thawing fish carries a bacteria that causes any creature infected with it to undergo reverse evolution. And we all know what that means …

Universal’s Monster on the Campus (1958) is a good example of the studio’s SF/horror output in the late 50s: low budget, hasty shooting schedules, a weak script and actors with little marquee value — but still containing a little bit of major studio class, lifting it above many of the B-movies churned out at the time. While modestly popular at the time of its release, it is best remembered today for being directed by the great Jack Arnold.

As the story unfolds we meet the film’s central players: Blake’s wife Madeline (Joanna Moore), his assistant, nurse Molly Riordan (Helen Westcott) and his student and apparently teacher’s assistant Jimmy Flanders (Troy Donahue), as well as Jimmy’s dog, Samson. Samson is the first one to get affected by the fishy bacteria as he laps up the meltwater from the specimen. It doesn’t take long for him to develop sabre teeth and go all Neanderthal. At this point Prof. Blake has no idea as to what causes Samson’s transformation.

Later, after having this unique specimen lying about in room temperature without processing it in any way, Blake cuts his hand on its teeth, after having shoved his fist into the mouth of these unique specimen he has paid a fortune to have delivered from Madagascar, which must by thus stage be rotting on his desk. Or to be precise: the dead fish actually bites him – an oddity that is never explained. Some time later a monstrous creature attacks nurse Riordan while she is in the company of Blake. When they are found, Molly has been killed and strung up a tree by her hair, and Blake lies unconscious with his clothes torn and has no memory of what has happened.

Of course, by this time the audience has figured out what is going on, but the movie dutyfully goes on with its police investigation led by Lt Stevens (Judson Pratt). The police naturally suspect Blake, but find giant foot and finger prints that obviously don’t match Blake’s. Oh, and back at the lab, Samson is now back to normal.

Later Blake waves away a dragonfly that feeds on his precious fish. The dragonfly reverts into its ancestor, a giant dragonfly, and attacks Jimmy and his girlfriend Sylvia (Nancy Walters). Meanwhile, Blake has started analysing the fish and discovers that it has something something or other prehistoric bacteria, which should not be scientifically possible, and tries to convince his superior Dr. Cole (the great Whit Bissell) of his discovery, but Cole waves away his crazy theories. Later the giant dragonfly comes a-knocking on Blake’s lab window. Blake uses the fish as bait, and when the dragonfly lands on the fish, he impales it with a long knife which also cuts into the fish. He then accidentally drips some of the fish blood into his pipe holder. After taking a puff at his pipe, Blake transforms into a Neanderthal man (this is supposed to be the great reveal), trashes his lab and kills the police officer assigned to protect him from the monster on the campus.

By this time, Blake is convinced that the monster is a “sub-human” somehow connected to the fossil fish and calls up a Dr. Moreau at Madagascar, and finds out that the fish has been treated with gamma rays to “prevent decay”, and that this has somehow activated the strange bacteria. Still, despite having scratched his hand on its teeth, watched a dragonfly revert into its prehistoric state after eating the fish and having woke up in the vicinity of two murders committed by the monster with torn clothes, he still doesn’t put two and two together – that he is the monster he is hunting. It isn’t until Jimmy mentions that Samson lapped the meltwater from the fish that the other shoe drops.

Once the penny has dropped, Blake sets out to prove both his theory and the fact that he is the person responsible for the murders. In is remote cabin, he devices a setup with a tape recorder and trip wire activated cameras, and injects himself with the bacteria. Transforming once again into a Neanderthal man, he scares the bejeezus out of the local ranger who calls for backup. The police arrive with Madeline and Dr. Cole in tow, finding Blake in his human form. Even though Blake already has his evidence, he now seemingly needs to make things right, and injects himself one more time in front of the whole group, attacking Madeline. And we can all guess how this ends.

Background & Analysis

In the first half of the 50s, Universal made two of the best science fiction movies of the decade, It Came from Outer Space (1953, review) and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), as well as a handful of other high quality SF/horror movies. Almost all of them were directed by Jack Arnold, who invented or at least cemented many of the tropes of the genre. By 1956, however, major studios’ interest in science fiction as prestige projects waned due to the underwhelming box office performance by a couple of big-budget SF movies. At the same time small studios like AIP proved that all you really needed to make money at the drive-in circuit was a monster and a damsel in distress – and preferably a teenager or two. Story, big-name actors and production values were secondary to the teen crowd that frequented these showings. Univeral latched on to the trend and tried to emulate the success that studios like AIP and United Artists had with their SF/monster romps.

Of Universal’s late 50s output, Monster on the Campus (1958) is the one that most closely resembles these super-low-budget outings often featuring scientists transforming into monsters. The script is credited to merited SF author and usually intelligent screenwriter David Duncan, but much points to the fact it was was finished by committee. For example, in an interview with Tom Weaver, Duncan says that he wasn’t aware that Dr. Blake was bitten by the fish in the finished film. In the same interview, Duncan tells Weaver that he was commissioned by Universal to write a couple of science fiction scripts, which became The Thing That Couldn’t Die (which is strictly not SF) and Monster on the Campus. Duncan says what inspired him to write the script was a lot of writing in scientific publications about the catching of a live coelacanth off the coast of Madagascar. According to the Smithsonian, a coelacanth exhibition was opened in Washington in 1957, featuring a model of the fish that Duncan is talking about, and it would probably have made a few headlines in the science press.

So the fish featured in the movie is a real thing – it’s a rare species of fish that has remained more or less unchanged for over 400 million years, not “a million years” as Blake claims in the movie. It was “rediscovered” (that is, by white people) in 1938 when a scientist spotted it being sold at a fish market in South Africa. By 1957 it was discovered that it was occasionally caught in fishermen’s nets outside the Comoro Islands between Madagascar and Tanzania. The fact that it has changed so little over the years makes it interesting for studing the evolution of other fish and vertebrates.

Incidentally, I had a hard time reconciling the fish’s written name with the way it was pronounced in the film. Blake talks about a [see-lee-kanth] while my very basic understanding of Latin pronunciation would suggest that it should be pronounced [koh-eh-lah-kanth]. However, because of diphtong migrations and the change in the pronunciation of the latin C between old Latin and church Latin, as well as the world’s English speakers inability to pronounce any other languages correctly, it seems the preferred English pronunciation is actually [see-luh-kanth], which is pretty much how it is pronounced in the film.

Fish aside, the two major inspirations for Monster on the Campus seem to be Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, as well as United Artists’ 1953 movie The Neanderthal Man (review), directed by E.A. Dupont and starring Robert Shayne in a rare lead – itself taking its beats from Robert Louis Stevenson’s story. The premise of the 1953 movie is that Robert Shayne wants to prove his scientific theory that Neanderthals were smarter than Homo Sapiens by reverting himself to a Neanderthal by means of serum injection. In terms of plot, however, it is basically the same as Monster on the Campus: a scientist sporadically reverts into an ape man, and the rest of the cast scramble to find out who or what is responsible for a string of attacks and murders committed by some sort of monster.

The Neanderthal Man was not a particularly good film, it was marred by a completely illogical script full of purple dialogue, and notoriously bad special effects. It did, however, have a couple of refreshingly perverse ideas that somehow slipped past production code censors, and a marvelously hammy Robert Shayne spouting absolutely ridiculous lines. Monster on the Campus could have benefited from a little more of this kind of schlockiness – the screenwriters, director Arnold and the actors all take this ludicrous tale a little too seriously.

Jack Arnold was not happy with the movie. In an interview with Mark McGee (as relayed by Bill Warren) he stated that “I didn’t really hate it, but I don’t think it was up to the other films that I’d done”. Apparently, he got attached to the movie through its producer Joseph Gershenson. Gershenson was the head of the music department at Universal and desperately wanted to produce a movie. He had several dozen associate and executive producer credits going back as far as 1940, but hadn’t been allowed to produce at Universal since 1948. According to Arnold, Monster on the Campus was the only film the studio was prepared to give him, and asked Arnold direct it. Arnold says he wasn’t particularly keen on the project, but decided to do it because he liked Gershenson (and since he was still under contract at the studio, his other option was to be put on suspension).

Monster on the Campus was shot over 12 days and reportedly had a budget of $240,000, two-and-a-half times higher than AIP’s corresponding films. Of course, a major studio had all kinds of overhead costs that ate up much of said budget, one of the reasons that studios like United Artists and 20th Century-Fox primarily bought their B-movies from small, independent production companies. Universal, however, generally kept their productions in-house. Campus exteriors were shot at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and the rest of the movie either at Universal Studios or studio backlots.

The idea of shape-shifting as a transgression of societal and moral bounds go back to early mythology – shedding the veneer of humanity, revealing the animalistic nature inside all of us. But it was with the rise of Romaticism and the Gothic that these themes exploded. One precedent, which didn’t feature a physical transformation pers se, was Matthew Gregory Lewis’ scandalous novel The Monk (1796), which features a pious monk who gives in to his lustful urges, setting off a chain of events that leave him damned. The theme ran deep, and deeply influenced by Lewis, in several great literary works of the 19th century, such as The Devil’s Elixir’s by E.T.A. Hoffmann and Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Preceding Lewis was Goethe’s Faust (1790), a tale of a scholar being lured to the dark side by the devil, in essence allowing himself to be corrupted through ambition.

All of these works no doubt inspired Robert Louis Stevenson in the creation of his classic novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1886. Stevenson’s novella has been much mangled from the very first stage adaptations that the early film were based upon, often rendering Jekyll’s motivations for inventing the transformative potion inexplicable – and turning his transformation into Hyde into some degree of an accident. In the early films his motives were often to “separate the good and evil in Man”, but to what end usually remains murky. In the book, however, Jekyll had no such noble aspirations. The serum he created was simply a shape-shifting serum that allowed the respected Victorian Dr. Jekyll to go out and commit debauchery at night without being recognised.

Still, the trope of the noble scientist “whose reach exceeds his grasp” accidentally turning himself into a monster through righteous but misguided actions quickly became a trope in horror and science fiction movies following the successes of the 1920 and 1931 movie versions of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Closely related is the werewolf trope created by Universal in 1941 – and a whole slew of horror films churned out in the 40s and 50s were amalgams of the Jekyll/Hyde and the werewolf traditions. Only in 1958 at least three Hollywood films in the subgenre were released: The Fly (review), The Hideous Sun Demon (review) and Monster on the Campus. Add to this the outlier How to Make a Monster (review) and the Mexican film The New Invisible Man (review).

Some academics and critics like to place Monster on the Campus in the tradition of the atomic scare movies of the 50s and 60s. And sure enough, it is gamma rays that are the source of all the trouble, as they have altered the fish’s bacteria. However, this is only mentioned in passing once, and feels more like the way in which B-movies used radiation as magic, throwing it in as an explanation for anything the screenwriters couldn’t come up with an explanation for. Wikipedia has a long section on academic analysis made about the themes of the movie, from “issues of conformity and individuality” to “the demonized black male student, threatening to contaminate the purity of white women”. And while I always applaud efforts to take B-movies seriously on a thematic level, in the case of Monster on the Campus, all of this is, in my opinion, hogwash. Nobody tried to make a social commentary with Monster on the Campus. David Duncan wrote a quickie science fiction script inspired by an old fish because he was commissioned by Universal to write a quickie science fiction script for the drive-in audience. Joe Gershenson produced it because the studio wouldn’t let him produce anything else and Jack Arnold reluctantly directed it as a favour to Gershenson. Everybody knew it was primarily going to be playing the drive-in circuit, where nobody cared about its perceived social commentary on “individuality vs. conformity”. Sure, such themes can be gleaned from the film, but that’s due the fact that they were part of the cultural tapestry of the era, and not because anyone involved in the movie set out to explore serious social issues with the picture.

The result is without doubt Jack Arnold’s weakest sci-fi movie, in large part because of its script, but also due to the sub-par production values and Arnold’s apparent lack of enthusiasm for the project.

First of all, the central premise is too dumb even for a dumb drive-in movie. The idea that an irradiated bacteria from a fish would cause animals and humans to de-evolve into prehistoric versions of their species simply defies not only any scientific fact or logic, but just common sense. Second, the film lacks anything resembling a real dramatic plot. It simply regurgitates the same ideas over and over without advancing the story. The only thing keeping the whole thing going is Prof. Blake’s baffling inability to make the connection between the prehistoric fish at the centre of every development in the film, and both the strange break-ins and attacks, and the de-evolving of the animals. Even when he wakes up in the vicinity of all the attacks, with memory loss and torn clothes does he suspect he is the culprit. Third, the idea is so contrived that the filmmakers need to bend over backwards in order to get Blake infected with the bacteria – a dead fish biting him, and him stabbing a gigantic dragonfly into the fish, and then dripping the fish’s blood into the pipe bowl.

The ending is likewise contrived, stupid, irresponsible and unscientific. In order to get proof, Blake sets up the whole tripwire-camera and tape recorder setup at his cabin, and later injects himself a fourth time – with the police and scientific community present, as well as his wife – in order to prove he is the monster, resulting in the police shooting him to death. Why? Could he not just have had the police lock him up in a cell and have everyone observe his transformation under controlled circumstances? He is a scientist, after all.

The special effects are sub-par for a Universal monster movie. Universal’s head of makeup, Bud Westmore, is credited for the makeup, but he probably never set foot on the stage. The creature design follows the classic low-budget formula of having the monster in pants and a shirt in order to save on budget and shooting schedule. The face makeup for the monster is just a pull-over face mask – and commentators point out that it is the same mask used for for Hyde in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953). That would certainly make sense, since Hyde was played by the same actor/stuntman who plays the monster in Monster on the Campus, Eddie Parker. The mask was designed by Jack Kevan, who also probably did most of the other creature work on the picture. The giant fish looks OK, but the giant dragonfly is terrible, it’s just a static, immobile plastic model.

With big-studio resources and a director like Jack Arnold on hand, as well as a cinematographer like Russell Metty, who later won an Oscar for his work on Spartacus (1961), the cinematography and visuals of the movie are naturally professional and competent. But this is Jack Arnold simply going through the motions. There’s no enthusiasm or originality on display, and none of the visual poetry seen in most of his SF movies. “Special photography” is credited to visual effects master Clifford Stine, but the visual effects here are few and far between, and really only consists of a couple of lap dissolve transformations. These are adequately done, but were old hat in 1958. Universal didn’t even bother to compose new music for the film, and the score is comprised of stock recordings.

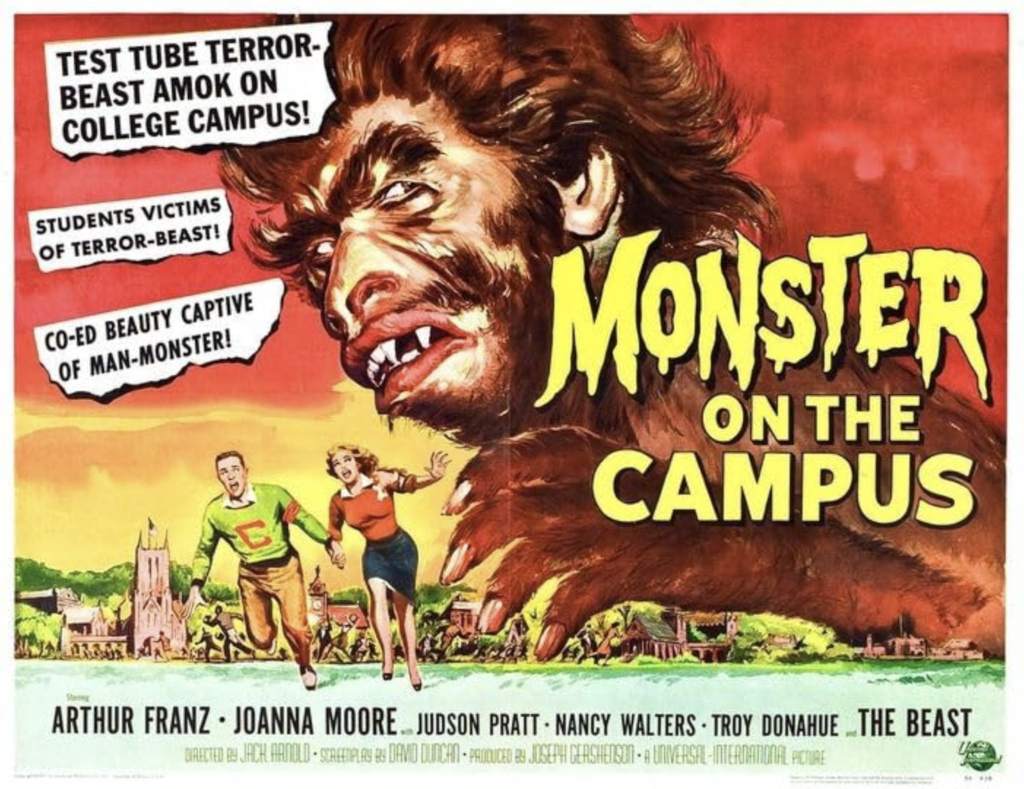

The taglines of the poster leaned heavily into the teen market: “Co-ed beauty captive of man-monster”, “Students victims of terror beast!”. In fact, students or teenagers hardly play into the plot in any way, which is in and of itself an achievement of sorts for a film based on a college campus. The only teens in the picture are Jimmy and his girlfriend, and none of them are ever captives of a man-monster nor victims of a terror beast. The only thing that attacks them, barely, is a dragonfly. And really, it’s more an annoyance than an attack. The two teens are so redundant they could have been entirely taken out of the movie without any consequence on the plot.

Arthur Franz was a reliable, understated actor that tended to bring focus and believability to such ridiculous fare as The Flame Barrier (1858, review). As the centerpiece of Monster on the Campus, he brings both a sympathetic warmness and a sense of intelligence, despite his idiotic actions. Joanna Moore, an actress who deserved to do better things in her career than she did, also delivers a strong performance and is able to bring a nuance to her unthankful role that transcends the script. Other performances are by the book – Helen Westcott is fun as the nurse flirting with Dr. Blake, and who unfortunately ends up strung from a tree. Sf aficionados will easily spot character actors Phil Harvey and Whit Bissell in the cast, and then there’s Troy Donahue playing one of the teenagers. Donahue, of course, would go on to 15 minutes of fame as a blonde heartthrob in the 60s.

Despite its shortcomings, Monster on the Campus is a reasonably entertaining film if you’re in the mood for a bad 50s B-movie. Neverthleless, it has little to recommend it to anyone but completists. The script would have required a director less serious than Jack Arnold and a more outrageous mad scienist in order to make it work as a bad movie howler, or conversely a better and more intelligent script in order to make it work as a Jack Arnold film. As it is, it sits uncomfortably in between the two, with an approach too serious for laughs (other than the unintended one) and too dramatically and visually weak for it to be taken seriously.

Reception & Legacy

Monster on the Campus premiered a week before Christmas 1958, making this the last science fiction movie of the year – and the second-to-last movie of 1958 which I review (I’m currently also working on a review of the Italian SF comedy Totò nella luna, released in November, 1958). It played as the bottom bill to Universal’s British import Blood of the Vampire (review) I have found no box office numbers, but trade papers indicate that Monster on the Campus pulled in 122 percent of “normal gross” in 1959, which I take means that the movie was moderately successful with audiences.

Because of its status as second billing on a B-movie bill, Monster on the Campus didn’t receive many reviews in contempory publications. However, where it was reviewed it received fairly good notices. Harrison’s Reports called it “a pretty good program picture of its kind” and that it “has been given a good treatment and provides more than a fair share of the chills and thrills than one anticipates”. Whit in Variety wrote: “Universal comes up with a pretty fair shocker in this expertly produced story of retrogression. Its premise is logically developed without any great strain on the imagination, acting is convincing, and there’s a general professional air about the unfoldment.” The Hollywood Reporter’s Jack Moffitt was likewise positive: “By emphasizing the human rather than the monstrous side of this modern ‘Dr. Jekyll’ story, Franz gives gentlemanly and scholastic values few boogey tales possess”.

Not all were thrilled, though. British Monthly Film Bulletin called it “a depressing variation on the Jekyll-and-Hyde theme, tailored for the teenage horror market and marking a further decline in Jack Arnold’s melancholy and at one time thoughtful talent”.

Fillm scholar John Baxter has a whole chapter on Jack Arnold in his pioneering 1970 book Science Fiction in the Cinema, where he praises Arnold as an exceptional sci-fi director. However, regarding Monster on the Campus, Baxter writes it “has little to recommend it” and that it is “lamentably feeble”. In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy calls notes that “the script lacks any sparkle”. Bill Warren writes in Keep Watching the Skies! (2009): “The trouble is that it’s routine, unimaginative and foolish. A decent performance by Arthur Franz and a few good night scenes don’t save this from being Jack Arnold’s worst science fiction film.”

Monster on the Campus is not a favourite among modern critics, either. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings writes: “This is probably the weakest of the several science fiction movies directed by Jack Arnold during the fifties. In some ways, it works well enough; however, it gets fairly silly at times.” Ed Howard at Only the Cinema calls the film “a weird, unintentionally goofy bit of horror/sci-fi camp, saddled with one of the most inane, scientifically implausible, outright ludicrous plots in a genre not exactly renowned for its level-headedness or scientific acuity”. Richard Scheib at Moria gives it 2/5 stars, saying it is “not bad enough to be entertaining and yet lacks the tucked-away gems to make it essential Golden Turkey viewing”. A tad more positive is Jessica Amanda Salomonsen, or “Paghat the Ratgirl” at Weird Wild Realms: “There’s plenty to find fault with if one wishes. The film is overall strictly by the numbers with no real surprises in it, & a few contradictions such as the cave man sometimes having big feet sometimes not. But it has a hefty dose of charm for anyone who rather enjoys 1950s drive-in movie horror films.”

Cast & Crew

I have written about director Jack Arnold before in many posts, for more on him, see for example my review of The Space Children, or follow the link on his name above to see a list of all of his films reviewed on this site.

Screenwriter David Duncan is best known for penning the script for George Pal’s classic The Time Machine (1960), but he was also a noted author in the pulp vein and a frequent screenwriter. He started his career fairly late in life – his first novel The Shade of Time – about “atomic displacement” – was published in 1946, after the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He wrote three more SF novels in the 50s, of which Dark Dominion (1954) is the best known. The book is essentially a space race tale, in which scientists and the military butt heads in a vast research facility in the US, where the Americans are building a nuclear-armed space station. The book has a mixed reputation, being described by some as “cold war soap opera” or more as a technothriller than classic SF. But he also gets some praise for remarking upon philosophical and social issues without the black-and-white view of say, a Robert Heinlein. John Clute at the Science Fiction Encyclopedia writes that Duncan’s work is “quietly eloquent, inherently memorable, worth remarking upon”. Duncan also wrote a number of detective and mystery stories, but more or less left writing behind in the 70s.

David Duncan contributed to a dozen movie screenplays and around as many TV shows, in different genres. He wrote a couple of adventure films in the mid-50s, but after that he was mainly hired for science fiction films. His first SF job in the movies was to write the story for the American version of Rodan (1956, review). He wrote the first draft of United Artists’ above-par monster movie The Monster That Challenged the World (1957, review), but in his own words got stuck, and the project was handed to Patricia “Pat” Fielder, who did an excellent job with it. Next he was hired by Warner to write The Black Scorpion (1957, review), and then by Universal, for whom he wrote Monster on the Campus (1958). George Pal commissioned him to turn H.G. Wells‘ novel The Time Machine into a movie in 1960, and according to an interview with Sandra Petrovic, it remained the script he was most satisfied with. He also contributed to the scripts of Universal’s The Leech Woman (1960) and 20th Century-Fox’s classic shrinkage picture Fantastic Voyage (1966).

Male lead Arthur Franz had quite a successful career as a supporting actor in both B movies and A efforts like The Caine Mutiny (1954) and Sands if Iwo Jima (1949). He may be best remembered for playing the lead as a deranged murderer in The Sniper (1952). He appeared in a large number of science fiction series on TV and a few films, we have previously reviewed him on this blog in one of the major roles of the 1951 film Flight to Mars (1951, review) and as the adult lead in Invaders from Mars (1953, review). He also appeared in The Flame Barrier (1958, review), Monster on the Campus (1958), The Atomic Submarine (1959), in all of which he played the lead. He also narrated King Monster in 1976.

A talented actress with a trying childhood, Joanna Moore’s career was derailed by substance abuse and mental problems. She lost her family in a car accident when she was a child and spent some time a foster home. Nevertheless, she broke onto the Hollywood scene in the late 50s through a beauty contest, and quickly garnered a reputation for playing femme fatales and “wily women” – often leading ladies in B-movies, with a few supporting roles in A-films like Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958) and Daniel Mann’s The Last Angry Man (1959). She had large supporting roles in films like Edward Dmytryk’s Walk on the Wild Side (1962) and the Elvis vehicle Follow That Dream (1962), as well as a small but memorable one on in the science fiction comedy Son of Flubber (1962). However, much of her 60s were spent in TV.

Moore entered her third marriage by the age of 29 in 1963, and has two children, before the stormy relationship ended in yet another divorce in 1967, after which she started suffering from depression and developed what would become a very severe alcohol and drug addiction. She still had a few good years of acting before her, though, playing the female lead in the science fiction thriller Countdown (1967), opposite James Caan and Robert Duvall, and had a minor role in the star-studded historical drama film The Hindenburg (1975). However, by the late 70s her irrational, “bizarre” behaviour and her drug and alcohol abuse effectively ended her acting career. She passed away in 1996. Her sci-fi output inclued Monster on the Campus (1958), Son of Flubber (1962) and Countdown (1967).

Joanna Moore’s daughter is Tatum O’Neal, who went on to win an Oscar and a Golden Globe for her role in Paper Moon (1973), and appeared in a string of popular films and TV shows up until 2021. Joanna’s son Griffin O’Neal had a short-lived movie career playing leads or large supports in around a dozen low-budget movies in the 80s and early 90s, including the Charlie Sheen horror The Wraith (1986) and April Fool’s Day (1986).

Troy Donahue, one of the two teens in Monster on the Campus, is jokingly known as the heartthrob who was a major star for 15 minutes before everyone discovered that he couldn’t act, a fact that he himself acknowledged in later years. Dropping out of journalism studies at Columbia University to become a Hollywood actor, the strikingly handsome, blonde 21-year-old was picked up by Universal in 1957 and put under contract. He played minor and supporting roles in a number of movies, including the SF efforts The Monolith Monsters (1957, review) and Monster on the Campus (1958), before he was let go in 1959 when MCA bought the Universal studio lot and ousted most of of Universal’s stock players.

However, Donahue was picked up by Warner Bros., who gave him a star turn in the sex-themed drama A Summer Place in 1960. The movie was a box office success and immediately turned Donahue into a teen idol. Warner followed it up with the tobacco empire drama Parrish (1961), where Donahue played the lead as the entrepreneur who gets caught up in a drama of money, power, women and class – which was an even bigger success. After this, he did a number films, mostly of the B-variety, with Warner. They were initially romantic dramas, drawing on his teen popularity (like Palm Springs Weekend, 1963), but toward the mid-60s, he seemingly tried to distance himself from his image of matinée idol with a western and a thriller. Eventually, he was let go by Warner as well, and fell on hard times. He did keep acting steadily from the mid-60s to his death in 2001, but the quality of the productions – as well as his income – declined steadily. At one point he was both heavily addicted to drugs and homeless, but was able to turn his life around. By the 80s he was still commanding the occasional B-movie lead in films that had some semblance of professionality, but by the 90s an increasing number of his movies were straight-to-video productions.

Donahue appeared in a number of science fiction movies: The Monolith Monsters (1957), Monster on the Campus (1958), AIP’s comedy Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon (1967), Fred Olen Ray’s Cyclone (1987), Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s The Drifting Classroom (1987), David DeCoteau’s Dr. Alien (1989) and Omega Cop (1990).

Nancy Walters, who plays Donahue’s girlfriend in Monster on the Campus (1958), was a fashion model who had a brief acting career in the 50s and 60s, and appeared in around half a dozen films, perhaps best known for her role as one of the women surrounding Elvis in Blue Hawaii (1961).

Dr. Blake’s superior in Monster on the Campus (1958) is played by sci-fi royalty Whit Bissell, best known, perhaps, for playing one of the central roles in Jack Arnold’s Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review). During his career, Bissell appeared in over 100 movies and 200 TV shows. He took part in 10 science fiction movies, and played the mad scientist in AIP’s cult classics I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review) and its inferior follow-up I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957, review). He had a small role as a doctor in the end of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), played one of the time traveller’s friends seen in the beginning of The Time Machine (1960), and had the small but symbolically important role as Gov. Santini in Soylent Green (1973).

I have reviewed numerous pictures involving legendary stuntman Eddie Parker, but have still not covered him in any greater length, and seeing as he has a prominent role as the monster in Monster on the Campus, this seems like a good time.

Edwin “Eddie” Parker was born in the year 1900 and appeared as a stuntman, suit actor or bit-part player in well over 450 films, serials and TV shows, at least between 1931 and 1960. He played cowboys, henchmen, brawlers, security guards, cops, robbers, soldiers, Frankenstein’s monsters, mummies, wolfmen, Mr. Hydes, mole men, and even Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers and Batman, almost always uncredited. He was a staple in western serials in the 30s, and was particularly adept at fisticuffs. John Wayne has mentioned that it was Wayne and Parker who developed the so-called “no-contact punch”, which became the standard technique for delivering on-screen blows in fistfights. The idea was to punch just a couple of inches past the opponents chin, while the opponent yanked his head backward to indicate a hit – all filmed from an angle behind the opponent, so that the back the opponent’s head blocked the near-miss from view, while the aggressor could follow through the punch, resulting in an explosive energy being caught on camera.

Parker’s road to Hollywood was not straightforward. The 6’3 or 190 cm tall actor began performing as a singer and dancer, as well as vaudeville performer, but had to work day jobs to make ends meet in the beginning. He worked as a newspaper clerk, a mortician and as a florist before he was able to commit to the stage full time. When the vaudeville scene crashed with the coming of talkies, he transition to film in the early thirties. He was there at the beginning of Republic Pictures, and soon became part of a group of stuntmen called The Cousins, who not only perfected their craft together, but also pushed Hollywood to professionalise stunt performing.

Recounting all the numerous horror and science fiction films that Parker’s been involved with would be a daunting task, but his first SF production were Universal serials, where he, among other things, doubled for Buster Crabbe as Flash Gordon (review). He doubled for lead actor Lewis Wilson in the titular role of the serial Batman (1940, review) He played Frankenstein’s monster in Ghost of Frankenstein (1942, review), where he burned to death in the film’s finale and reportedly doubled for both Lon Chaney, Jr. and Bela Lugosi in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943, review), and went on to appear in numerous other Universal movies, including many of the Abbott and Costello monster pictures, where he played an assortment of boogiemen. He had a small role in Tarantula (1955, review) and played the mole man who pulls lead actress Cynthia Patrick underground in The Mole People (1956, review). He (possibly, this is unconfirmed) appeared again as Lugosi’s double in Ed Wood’s Bride of the Monster (1955, review). His role as the neanderthal Dr. Blake in Monster on the Campus (1958) was arguably his biggest role, although once again uncredited, and his last science fiction movie. Parker died in 1960 from a heart attack.

In a lesser role we se Phil Harvey, a Universal contract player who appeared in close to 20 films between 1956 and 1958, including three science fiction movies in 1957: The Deadly Mantis (review), The Land Unknown (review) and The Monolith Monsters (review). His last three roles at the studio were uncredited but parts, and he struck out as a freelancer in 1958. Harvey appeared in two AIP movies, Monster on the Campus (1958) and Why Must I Die (1960), and had a couple of TV guests spots. He called it quits in 1961 and became a music teacher, and later set up a camera shop.

In another small role we see another actor we have seen before on this blog, Ross Elliott, most notably as the male lead in the dreadful 1955 hee-haw comedy Carolina Cannonball (review). Unfortunately for Elliott, the film probably features the most inept “hero” of any Hollywood movie in history. Described as a “general utilitarian player”, New Yorker Ross’ clean-cut and somewhat nondescript features and a reliable talent provided him with a steady income for over four decades. Few of his film roles stand out as memorable, and he might be best remembered for walking out on his role as Lee Baldwin in the long-running soap opera General Hospital in 1965, a role which was then played by Peter Hansen from 1965 to his retirement in 2004. Leaving behind a proposed career in law, Ross came up through Broadway and moved to Hollywood after serving in WWII. Between 1943 and 1986 he appeared in close to 200 TV shows and over 60 films. He had robust supporting roles in SF movies like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), Tarantula (1955, review), and Indestructible Man (1956, review), as well as that rare lead in Carolina Cannonball, and he showed up in smaller roles in Monster on the Campus (1958) and The Crawling Hand (1963). He also appeared in a number of SF TV shows, including The Twilight Zone, The Time Tunnel, The Invaders, Wonder Woman and The Bionic Woman.

Janne Wass

Monster on the Campus. 1958, USA. Directed by Jack Arnold. Written by David Duncan. Starring: Athur Franz, Joanna Moore, Troy Donahue, Nancy Walters, Eddie Parker, Judson Pratt, Whit Bissell, Phil Harvey, Helen Westcott, Alexander Lockwood, Ross Elliott. Cinematography: Russell Metty. Editing: Ted Kent. Art direction: Alexander Golitzen. Makeup: Bud Westmore. Creature design: Jack Kevan. Produced by Joseph Gershenson for Universal.

Leave a comment