In a career-defining role as Jekyll/Hyde screen legend John Barrymore elevates this 1920 adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel from a run-of-the-mill potboiler to a minor masterpiece. Barrymore’s amazing physical transformation and magnetic charisma makes him this reviewer’s favourite Jekyll & Hyde of all time. (8/10)

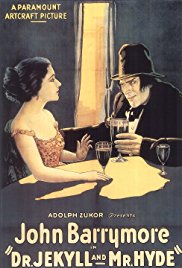

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 1920, USA. Directed by John S. Robertson. Written by: Clara Beranger, based on a play by Thomas Russell Sullivan. Based on the book Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. Starring: John Barrymore, Brandon Hurst, Martha Mansfield, Nita Naldi, Charles Lane. Produced by Adolph Zukor and Jesse S. Lasky. Tomatometer: 92 %. IMDb score: 7.0. Metascore: N/A.

In 1920 director John S. Robertson and in particular lead actor John Barrymore created what remains perhaps the best adaptation of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde-story, despite numerous later versions. It is a testament to the astounding talent of Barrymore that this silent version still creates such an impact. .

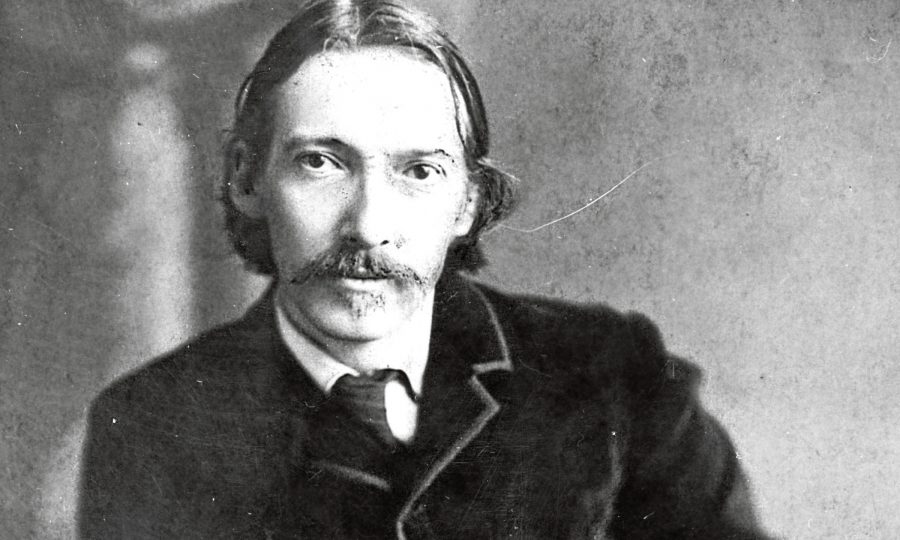

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote the novel Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1886, and it immediately became a bestseller. The story is told from the perspective of a Mr. Utterson, who follows the strange case of his friend Dr. Jekyll who works on a secret experiment at the time when a sinister and corrupted fellow known as Mr. Hyde turns up. Hyde starts acting violently, lewdly and becomes known as something of a pervert, later even commits murder (accidental such, it is later proven). Jekyll takes his own life and in a letter tells Utterson his story: how he as Jekyll had become hooked on immoral activities, but feared being caught and losing his position in society. Thus he created a potion that would change his appearance so he could frolic freely with what presumably was wild sex, drinking, fighting and gambling (we are never really told what Jekyll was up to before Hyde came along). Unfortunately the potion also creates a split personality, bringing out all the dark, animal instincts of Jekyll and manifesting themselves as Mr. Hyde. Jekyll turns himself back with an antidote, but unfortunately Hyde starts manifesting himself without the potion, and soon Jekyll runs out of a rare salt that he needs for the antidote, so finally he decides to end his life after a friend has died of a heart attack when accidentally witnessing Jekyll’s transformation.

This, though, is not the story seen on screen. As good as every film adaptation draws its inspiration from the stage plays written in 1887 by Thomas Russell Sullivan, Luella Forepaugh and George F. Fish. Both plays tell the story in a more traditional linear fashion, and remove the mystery of Mr. Hyde, instead focusing on the moral battle between Jekyll and Hyde. Both plays also add a female love interest, making the love story the dramatic centrepiece. The theatre performances utilised wigs and quick-changes in addition to the performances of the actors to make Jekyll change into Hyde before the eyes of the bewildered audience. Stage star Richard Mansfield did the double role with such aplomb that he came to define the role for over twenty years, until Barrymore came along. And naturally the film versions used all the trickery that the format allowed to outdo the transformations of the stage, employing editing, stop-motion photography (or rather pixilation) double exposures and fades.

The book describes Hyde as sinister and scary, but not deformed or monstrous, as many of the early films do. Stevenson described Hyde as smaller in stature than Jekyll, solved on stage and in film by making Hyde appear as a hunchback, stooped or a cripple – sometimes with unintentionally humorous results, see the review of the 1913 version above. The films also repeatedly forgets the fact that Jekyll himself was ”immoral” and created Hyde just to go about his business incognito.

The 1920 film takes elements from the plays, from previous films and from Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and adds in some details from the book. Dr. Jekyll (Barrymore) is portrayed as a philanthropist, an idealist and a brilliant scientist with strong morals and a god-fearing respect for his immortal soul. In a philosophical discussion an older gentleman and colleague, George Carewe (Brandon Hurst) – a man of the world – points out that in order to grow as a human being one must also have a taste of sin in one’s life, to which Jekyll fiercely protests. Jekyll is utterly afraid of losing his soul to the devil, and has this far lived a completely pure life. But intrigued, he nevertheless follows Carewe and a few friends to what appears to be a high class gentlemen’s club, where an Italian exotic dancer is performing. This Miss Gina is played by none other than the silent era femme fatale Nita Naldi, who unfortunately could have benefited from a few dancing lessons before shooting the film. But all her showing of bare ankles, a modest cleavage and shoulders rouses new feelings in Jekyll. After the show he even has a drink with the enticing Miss Gina. The intertitles let us know that this is the first time in his life that Jekyll has ”awakened to a sense of his baser nature”. In other words, this is the first time this man in his thirties, (Barrymore was 38 at the time) has been horny. What does that say about his fiancée?

Conversing later that evening with his good friend Dr. Lanyon (Charles Willis Lane), he proposes that it would be great if one could split the dark and light side of one’s personalities in two different bodies. Then the one body could be as perverted as the it wishes, while the other could keep its soul intact. “Preposterous!” Lanyon shouts, but it is too late. Jekyll readily starts making a potion that will not only turn his body into a different body, but apparently also collect all the ”baser nature” in this new vessel.

After this the story follows the basic premise. Hyde emerges, goes off doing bad stuff, ”leaving a trail of victims of his lewd acts”. He becomes greedy, haughty, naughty, perverted and evil. Jekyll starts turning without potion and starts sulking. With Hyde starting to skulk about the house with a ”free pass” written by Jekyll, Mr. Carewe, who also happens to be the father of Jekyll’s fiancée Millicent (Martha Mansfield), starts getting worried and demands answers as to what Jekyll’s connection to this vile creature Hyde is. Jekyll gets angry at these accusations, since it was Carewe that awakened his sense of his baser nature in the first place! In a fit of rage he turns into Hyde like some proto-Hulk in full view of Mr Carewe. Hyde sees no other way out than to bludgeon Carewe to death. Hyde then gropes at Millicent but at the last moment comes to his senses and drinks poison, killing himself.

The screenplay is written by Clara Beranger, and the logic makes no sense whatsoever. First we have the strange notion that a grown man has never felt sexual passion in his life, and the sight of an exotic dancer suddenly opens whole new worlds. If he has a fiancée, one would presume that even a man of 1920 has some sense of sexuality. And add to that the fact that he is, in fact, a seasoned physician, and as such would hardly have been a stranger to human sexuality.

Second, the idea of this personality split is muddled beyond comprehension. Jekyll wants to split his dark and light sides in two bodies. But in fact he doesn’t create a new body, he only changes his own body. One would presume that since Hyde has the sense to change back into Jekyll, the original Jekyll must still be in there somewhere, thus collapsing the idea of a complete body split. And since he also has the idea to take poison in the end, the soul must also be in there somewhere, thus making the whole thing utterly pointless. Remember that in the book Jekyll had no qualms about his soul, he simply wanted to be naughty without being caught. Being caught doesn’t seem to be a problem in the film, since it is his friends in high society that take him to the naughty club in the first place. In fact, this is much more of a Dorian Gray story – how to collect all your dark deeds in an independent and secret vessel – but in Oscar Wilde’s book there was a painting that was actually separate from the protagonist. The painting would absorb all the effects of the sins of Dorian Gray, while leaving the man himself physically unharmed by both vice and age. It is unclear though, whether Gray’s soul stayed intact – but the overall sense is that it did not. Here Beranger has included both Dorian and the painting in a single body, which makes the whole thing a bit confusing. Beranger even uses some lines from Dorian Gray – such as the famous quote “the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it”.

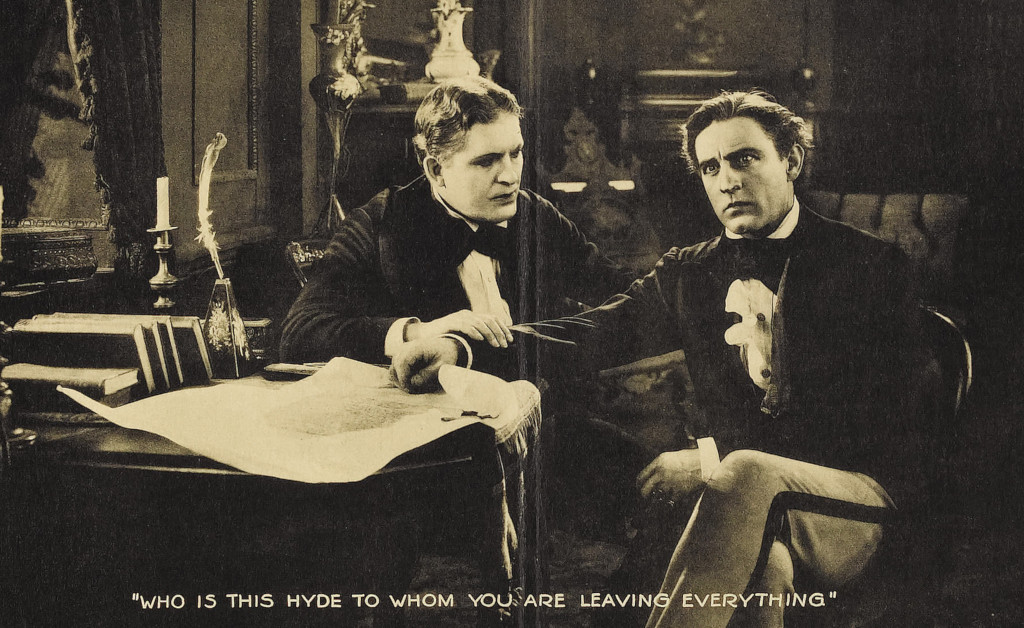

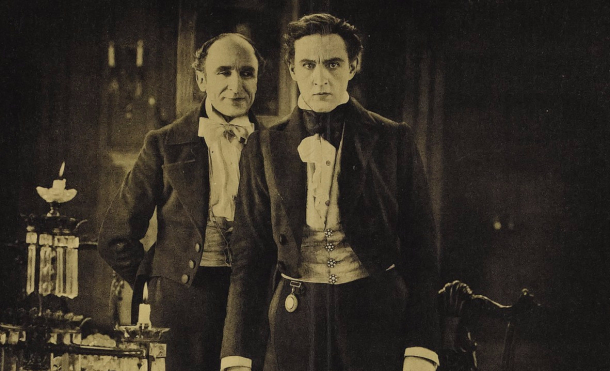

But this moral discussion isn’t really the draw of the film. It is Barrymore’s utterly brilliant and scenery-chewing performance. The first change of character is done complete in one take, without any cutting, diffusing of editing. Barrymore convulses, throws his long-ish backslicked hair into his face, and when looking up again the dashing, handsome, clean features have completely disappeared. In their place is a creep with a protruding, pointy chin, an elongated face, huge, crazy, bulging eyes and a menacing, lopsided, wry grin. No make-up, no wig, no nothing. And he is completely unrecognisable! Later the effect is enhanced with some make-up that gets a bit heavier as the story progresses, as well as a bizarre stripy wig with a top that makes him look almost like a conehead. In the end the change is actually made by a dissolve cut, but a very good one. In fact, the make-up is hardly necessary, especially not the obvious long-nailed rubber prosthetic fingers, that almost destroy the illusion (in one scene we can even see one of them fly across the screen as Barrymore convulses).

This is truly one of the great performances in movie history – as is the perfomance that Barrymore does when in character as Hyde. Seldom has a more charismatic, evil and vile, but at the same time strangely seductive and sexual character been seen on screen. Barrymore used the same kind of character for his hypnotic portrayal of the mentalist Svengali in the sadly obscure masterpiece with the same name in 1931.

As a leading man in stage productions as well, Barrymore had no problems with moving on to talking movies in the late Twenties. As a reviewer for The New York Times wrote in 1920: ”Those who expect the photoplay to be good because ‘it [the Jekyll/Hyde story] is just the thing for the movies will find that it is good because it is just the thing for John Barrymore. It is true that the screen lends itself peculiarly to the story, but it can be only a sufficient medium for Mr. Barrymore’s ability. It is what Mr. Barrymore does himself that makes the dual character of Jekyll and Hyde tremendous. His performance is one of pure motion-picture pantomime on as high a level as has ever been attained by anyone.”

On the other hand, Phil Hardy in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies writes: “Barrymore’s tour de force […] caused many critics to acclaim him the greatest screen actor yet. However, in hindsight, and comparing this picture to Wegener’s Der Golem (1920) or Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari (1919) and Veidt’s performance, not to mention Sjöström’s films in Sweden, Barrymore’s undoubtedly brilliant stagecraft, in the more intimate medium of cinema, comes across as excessive grimacing.”

I do understand those viewers who are put off by Barrymore’s broad hamming. As Hyde he turns every knob in his arsenal up to 11, munching his way through every set-piece in sight, steamrolling over all other actors, making later Heroes of Horror Ham like Bela Lugosi and Vincent Price seem like models of restraint. However, he does his role with such dignity and determination that it is impossible to take his eyes off him, creating a truly repulsive and genuinely scary character.

The film itself is not at all badly made. This was the very early days of German Expressionism, and Robertson clearly borrows some of its elements for his American film, such as the dark alleys and the cluttered, scary joints and basements where Hyde moves about. There are some very moody and cold visions of the underworld, and the almost surreal close-ups of Hyde’s manically glaring face are quite effective. The film came out the same year as the Expressionist masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr Caligari and two years before F.W. Murnau’s seminal horror film Nosferatu. The lighting in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is especially memorable, as it borrows heavily from European directors such as Murnau, Lang, August Blom and Holger-Madsen in utilising side-light, backlight and single-source light, such as a single lamp held by an old woman or the light from a stove which Barrymore uses to make his potion.

The birthplace of the horror film was undoubtedly Germany, starting with Paul Wegener’s The Student of Prague in 1913, and followed up important films such as The Golem (1915) directed by Wegener, Otto Rippert’s Homunculus (1916, review) and The Plague of Florence (1919), Robert Reinert’s Nerves (1919) and most importantly the work of Richard Oswald, including A Night of Horror (1916) and Unheimliche Geschichten (1919). However, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is arguably the first successful American horror feature film, and undoubtedly helped set the tone for the later films such as Universal’s horror franchise and the movies with Lon Chaney, the man with a thousand faces.

Chris Cabin of Slant Magazine feels that Robertson’s ”potent chilliness” has been largely underrated, and I partly agree with him. Visual effects are very scarce (I can now think of two or three) but beautifully done when used. I laud Robertson for not over-indulging in dissolves and replacement shots that never look quite satisfying any way you do them, but instead relying on Barrymore’s acting qualities and clever use of traditional editing to add and remove make-up. There is also a superb dream scene with a giant tarantula climbing into Jekyll’s bed, symbolising the evil taking over his mind. In fact this scene probably makes this film the first entry into the giant bug genre of science fiction.

One of the problems with this film, as stated earlier, is the screenplay. Not only is it utterly illogical, but it also comes to a bit of a standstill between the first transformation at the 25 minute mark and the murder of Carew at the 65 minute mark. That’s a fairly big chunk out of an 80 minutes long movie. Following the exploits of Hyde is rewarding enough, but that is pretty much thanks to Barrymore. Once you know the story (which movie-goers probably did even better in 1920 than today) nothing really happens during this long sequence that would have any large impact on the plot, and thus the film drags a bit. The psychological and social interactions between Jekyll, Carew and Lanyon are both interesting and insightful, but not much is made of the other two characters. The two female characters are completely redundant.

Martha Mansfield as Millicent gets more screen time, but but does little more than look sad or worried, or simply blank. Nita Naldi in her first ever film role is insecure, but that didn’t stop her from being hurled to instant stardom, later billed as ”the female Valentino”, as a pun on the great seducer of silent films. Julia Hurley as the uncredited landlady of Hyde’s makes good use of her small role, though, and is a lot of fun to watch.

Some reviewers have argued that the film itself, apart from Barrymore’s performance, doesn’t quite live up to the hype, for example the afore-mentioned NY Times reviewer, unfortunately uncredited: ”The production, aside from [Barrymore’s] performance, is uninspired. It is usual. The story has been movie-molded almost into obliteration of its original character, and those who were led to hope that it would escape the moral monger will be disappointed.” And it should be pointed out that this film still has its raunchy moments, although not explicit, they are clearly suggested. This film could not have been made during the Hays Code, introduced ten years later.

If not a cinema masterpiece, it is without doubt a classic, and thanks to John Barrymore still a highly tantalising piece of cinema craftsmanship. He gives one of the most memorable performances in movie history, and seldom has one actor alone been able to raise the quality of a film so drastically by sheer force of charisma and skill. While I have attested to his hamming earlier, it should be said that this hamming and scenery-chewing doesn’t come off as self-indulgent or tongue-in-cheek, simply as incredibly involved and straight-forward. David Keyes at cinemaphile.org writes: “The sight of the transformation is in a way nostalgically disturbing, because we recognize the transformations from other movies, yet never have they come through in this overwhelming magnitude.”

John Barrymore was the son of actors Maurice Barrymore and Georgie Drew Barrymore, and his brother Lionel (of The Mysterious Island) and sister Ethel were also actors. He appeared in his first major play in 1901, 19 years old. Starting off in both film and on stage in light comedy, slapstick and musicals, he gradually moved to more serious roles. Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde was his cinematic breakthrough, and as it premiered he was also making big waves on Broadway in the title role of Richard III. The film was actually filmed in different auditoriums at the New Amsterdam Opera House in New York, so that On screen he then played a string of high profile leads, including Sherlock Holmes, Beau Brummel, Captain Ahab and Don Juan between 1922 and 1926, later appearing in multiple serious drama films, many of which where huge successes. His portrayal of Hamlet on stage in 1922 was praised as the best Hamlet ever to appear on Broadway. During the 1920’s Barrymore was ”perhaps the most influential and idolised actor of his day”, according to his biographer. His career took a dip in the mid-1930’s due to severe alcoholism. After checking himself into rehab in 1935 he experienced a slight career revival, but never again achieved the same artistic or commercial heights as in his prime.

In 1931 Barrymore acted in what is one of this reviewers personal favourite movies, Svengali – maybe at the absolute pinnacle of his career, before it started going downhill. In this role he does more than slightly evoke his old Hyde character, but now with the added luxury of his beautifully spoken words. He only made one other foray into science fiction, that was with a forgettable performance in the 1941 comedy The Invisible Woman, review). His granddaughter is the now largely forgotten but not so long ago superstar Drew Barrymore, named after her great-grandmother. Despite the unanimous praise for his work, John Barrymore sadly never won an Oscar – although both his brother and sister did. This was largely due to the fact that he worked as a freelancer, and the studios barred all actors not working within the studio system from nominations. Rudolph Valentino did create an award in his name, though.

Canadian director John S. Robertson started making movies in 1915 for the Vitagraph company, had a successful career spanning 20 years, in which he made 57 films, sometimes with greats such as Mary Pickford, Greta Garbo, Nils Asther and Lionel Barrymore, but Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde remains his most successful film. His best known movies were made for Adolph Zukor’s and Jesse Lasky’s Famous Players-Lasky, that would later be reorganised as Paramount Pictures. Most of his films were shot in and around New York, where the company’s famous Astoria studio was finished just a month after the completion of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde had wrapped.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was the first major role for Brandon Hurst. He would later go on to specialise in playing villains, and did so in a number of big movies, and appeared in films like The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, with Lon Chaney), both the silent (1924) and sound (1940) versions of The Theif of Baghdad (Douglas Fairbanks, Conrad Veidt), The Man Who Laughs (1928, Conrad Veidt), Murders in the Rue Morgue, White Zombie (both 1932 with Bela Lugosi), and two John Ford-films at the end of his career.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde remains Martha Mansfield’s best remembered film. She was tragically burned to death during the filming of a historical drama in 1923. In a break during filming, she went out to her car, when her flimsy and flammable dress was lit by a match – it is unclear whether someone threw it out from a window or she dropped it herself when lighting a cigarette. Her driver and one of her co-stars tried to put out the fire with a coat, and were able to protect her head from burning, but they were too late, and Mansfield died later in hospital. Mansfield was considered a future star, and was only 24 at the time of her death.

Nita Naldi would later become one of Hollywood’s greatest vamps, especially appearing opposite Rudolph Valentino in many films, as well as in The Ten Commandments (1923) and the second film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, The Mountain Eagle (1925). Louis Wolheim would appear in many films as a burly brute, maybe most famously in Lewis Milestone’s 1930 drama All Quiet on the Western Front.

Despite her exotic stage name, Nita Naldi was born in New York to an Irish-American working class family as Mary Nonna Dooley. Back in the day many film actors used screen names, especially before 1915, when films were still viewed as vulgar and cheap entertainment unfit for serious stage actors. But as films grew ever more popular, serious and lengthy, film stars would also change their names to appear more mysterious and exotic – rather than as the working class Irish-American New York gals that they actually were. One of the first of the “mysterious foreign” screen vamps was the Cincinnati girl Theodosia Burr Goodman, better known as Theda Bara, said by her press agents to be the “daughter of an Arab sheik and a French mother, born in the Sahara desert”. Nita Naldi was generally seen as the successor to Theda Bara during the heyday of the sexy movie vamp. While the vamps have survived to this day, their appeal was somewhat lessened when flapper Clara Bow showed the audience that good girls knew all about sex, too, in the early twenties.

While Naldi had a good deal of stage experience from the legendary Ziegfield Follies, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was her first film role, and she does seem a tad out of her element, even if there’s nothing particularly wrong with her performance, perhaps underplaying her character out of fear of seeming too theatrical on screen. No danger of that with John Barrymore around, though. Before her definitive breakthrough opposite Rudolph Valentinto in Blood and Sand in 1923, she also had a small role in Harry Houdini’s 1922 science fiction film The Man from Beyond. Despite her immense popularity, Naldi sometimes got bad press because of her fluctuating weight, with critics calling her plump in some of her films. In 1926 she moved to Paris and got married, and made her three last films in Europe in 1926 and 1927. She moved back to New York in 1931 and filed for bankruptcy, and her marriage fell apart, even though she remained officially married until the death of her husband in 1945. She never made a talkie, even though she continued to act on stage and did a few gigs on TV during the early days of television. Naldi passed away in 1961, at the age of 66.

Another famous 1920 version of the Jekyll and Hyde story was the German Expressionist film The Head of Janus (Der Januskopf), made by master director F.W. Murnau. Since the studio was unable to obtain the rights for the book, Murnau changed all the names of the characters. The film was a veritable powerhouse of early horror films, and it is an unspeakable tragedy that it is among the lost films. Two years later F.W. Murnau made the legendary, but also unauthorised Dracula-adaptation Nosferatu. The writer was Hans Janovitz, who had the year before been one of the writers for the defining expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. Der Januskopf also starred Condrad Veidt, who starred as the murdering somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, and who later also became a major star of Hollywood, sometimes dubbed as the German Lon Chaney.

Der Januskopf was filmed by master cinematographer Karl Freund, who shot Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927, review), and became a huge influence in Hollywood with his work work in Dracula (1931), The Good Earth (1937), for which he won an Oscar, and Key Largo (1948). He also directed ten films in the US, among them The Mummy (1932) with Boris Karloff and Mad Love (1935, review) with Peter Lorre and Frankenstein (1931) star Colin Clive (which in turn was a remake of the German 1924 film The Hands of Orlac, (review) again starring Veidt, and directed by Caligari director Robert Wiene). Quite unexpectedly he later became a TV director for I Love Lucy. Murnau would later go on to direct highly influential films such as Nosferatu (1922), The Last man (Der letzte Mann, 1924) and Faust (1926), and is considered one of the pioneers of horror, expressionist and psychological cinema. He directed four acclaimed films in the USA, but remains best remembered for his German masterpieces.

Der Januskopf had nothing to do with sci-fi, though, as Veidt’s character was changed by the influence of a two-faced bust, and not by potions. But if there is a singe actor who might have rivalled John Barrymore in the role, it would have been Condrad Veidt.

Riding on the success of the Barrymore feature, a third Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was released in 1920, directed by J. Charles Haydon and starring Sheldon Lewis (review). The film was produced by Louis B. Mayer for the Pioneer Film Corporation, and Mayer (who later founded MGM) was worried about copyright issues, so he changed the plot significantly and moved it to New York. Generally considered inferior to both the German version and the Robertson version, the film is largely forgotten today, to the point that I can’t even find it online, even though it is in the public domain and available on DVD. Thus I haven’t seen it, but I have ordered it, and will get back to you later this summer with a review.

At least 17(!) adaptations of, riffs on or spoofs of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were made for the screen before 1920, mostly American productions, but a few British, two German and one Danish film. For the most part, they have been lost, but at least two of them exist, a 1912 version directed by Lucius Henderson (review) and a 1913 adaptation directed by Herbert Brenon (review). I have also written a few lines about the very first film adaptation, released in 1908 and directed by Otis Turner (review). John Barrymore wasn’t the first big star to take on the role either. In the very first movie, the role was created by Hobart Bosworth, who later became known as The Dean of Hollywood due to his tremendous influence on the creation of Tinseltown. German star Alwin Neuss portrayed the role twice, first in the Danish film Den Skaebnesvangre Opfindelse, directed by August Blom (see The End of the World, 1916, review), and later in the German film Der Andere, directed by none other than the afore-mentioned Richard Oswald. Neuss was best known for his string of films portraying Sherlock Holmes, including the first ever feature film adaptation of The Hound of Baskerville, again directed by Oswald, in 1914. King Baggot, who was one of the biggest stars in the world in 1913, played the part, and in 1915 the role was done by the US screen’s virst vamp, Helen Gardner, as the first female Jekyll/Hyde. And finally, in 1916, the role was played to comical effect by comedy star Harold Lloyd.

While occasionally clunky and sometimes a bit snoozy, I still consider the 1920 adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde the best one ever put on screen, which partly has to do with the fact that surprisingly few adaptations have actually retold the original story. After Robertson’s film, it’s really only 1931 Fredric March and the 1941 Spencer Tracy (review) versions that have kept the film within its Victorian setting and basically held on to the “original” stage plot – there has never been a version that would have put the novella on the screen truthfully.

While the 1931 version is perhaps the best known one, partially due to Fredric March’s Oscar win, it is the one out of the three that has left me the coldest, perhaps because the make-up is so odd. March’s makeup never looked particularly scary to me, and always made him look more like a goofy ape-man, which basically ruins the film for me. Barrymore’s, on the other hand, is truly creepy and repulsive, even if I could have done without his rubber fingers. Tracy’s Jekyll/Hyde is oddly under-appreciated, and I think Ingrid Bergman is absolutely superb in the movie. The psychological horror in the Tracy version is even more startling than the pre-code 1920 film’s, even if Robertson’s version is more violent and lewd.

It is also a testament to the film that it feels like the one with the most intellectual depth, despite the fact that Mammoulian and the director of the 1941 version, Victor Fleming, had sound and dialogue to aid them. As David Keyes writes in cinemaphile.org: “The movie’s images are detailed beyond belief, but they don’t interfere with the story’s subtext, which says that, in all of us, there is an uncontrollable force that lusts for sensations beyond the barriers of human decency. […] John S. Robertson’s vision is not boggled down by repetition or clichés, and he breaks from the shackles of Stevenson’s immortal story in every detail. […] This is because the sights in the silent version are loaded with depth and intrigue–something the later versions lacked.”

I know most critics disagree with me and Keyes on this point, preferring Rouben Mammoulian’s 1931 direction, but they are wrong and we are right. There, now that’s settled.

Janne Wass

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 1920, USA. Directed by John S. Robertson. Written by: Clara Beranger, based on a play by Thomas Russell Sullivan. Based on the books Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (uncredited). Starring: John Barrymore, Brandon Hurst, Martha Mansfield, Charles Lane. Cecil Clovelly, Nita Naldi, Louis Wolheim, Julia Hurley. Cinematography: Roy F. Overbaugh. Art direction: Clark Robinson, Charles O. Seessel. Produced by Adolph Zukor and Jesse S. Lasky for Lasky Famous-Players.

Leave a comment