Released in 1953, a year before Godzilla, the Beast was the original kaiju. Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion magic elevates this movie about a radioactive dinosaur wreaking havoc in New York from run-of-the-mill monster action to full-blown classic. 7/10

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. 1953, USA. Directed by Eugène Lourié. Written by Lou Morheim, Fred Freiberger, et.al. Suggested by story by Ray Bradbury. Starring: Paul Hubschmid, Paula Raymond, Cecil Kellaway, Kenneth Tobey. Produced by Jack Dietz. IMSb: 6.7/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 95/100. Metacritic: N/A.

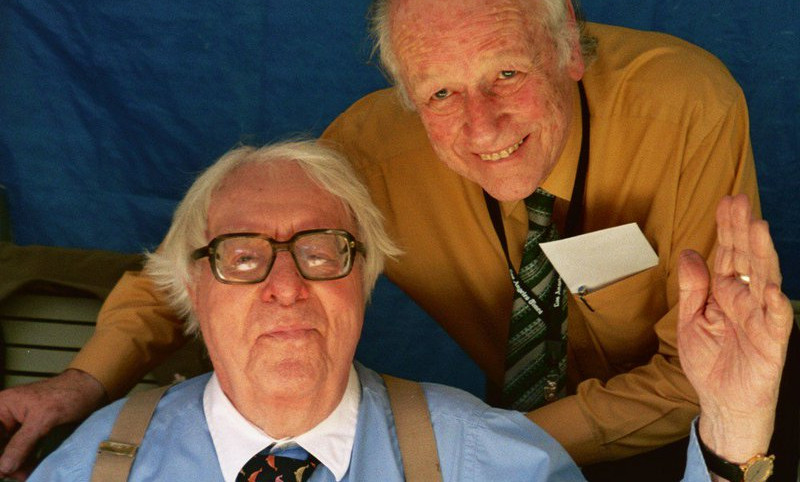

Some years back I worked as a foreign affairs editor at one of the top newspapers in Finland. One evening as I sat at my desk I saw the newsflash of Ray Harryhausen’s death. Strictly speaking, movies were not my jurisdiction, but I knew that the culture pages were already done and because of the late hour and recent cut-backs we were working on a skeleton crew, so I decided to walk down to the news desk to make sure they hadn’t missed the the flash.

”So, I suppose someone here is doing a bit on Ray Harryhausen’s death?” I asked.

I was met with blank stares and an unsettling silence.

”Ray who?”

I wasn’t surprised that the people my age or younger didn’t know Harryhausen, but I would have expected at least some of the senior editors on deck to recognise the name. But that’s when I realised just how much the world of movies and popular culture had moved on since Harryhausen. Apart from film nerds like me, no-one under 50 watched or cared much about films like The 7th Voyage of Sindbad or Jason and the Argonauts.

I ended up writing the the obituary myself.

Released in 1953, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was the first movie where Ray Harryhausen was personally in charge of the special effects, and it was made on the cheap by Jack Dietz’ company Mutual Pictures of California, and distributed by Warner Bros. to cash in on the re-release of King Kong (1933, review) in 1952. Even though the giant monster/dinosaur film had never really gone away, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms re-ignited the craze, and established some of the important tropes of the genre, that still haven’t completely gone away – the awakening (or creation) of the monster through nuclear energy, and the giant dragon/dinosaur rampaging through some major city.

Even if you haven’t seen the film, the plot will be familiar to you. It all starts somewhere along the Arctic Circle, where scientists and the military are performing nuclear weapons tests. Our protagonist Tom Nesbitt (Swiss Paul Hubschmid, credited as Paul Christian), along with a colleague, go out to take readings among in the glacier, but the colleague is killed by a giant dinosaur and Nesbitt scared nearly to death by it. If the movie was prompted by King Kong, then the opening sequence is quite clearly inspired by the Arctic setting of Howard Hawks‘ and Christian Nyby’s The Thing from Another World (1951, review). The research station is near identical, and director Eugène Lourié tries to emulate something of the documentary feel and overlapping dialogue. The movie even sports Kenneth Tobey as the non-nonsense Colonel Jack Evans. Tobey essentially played the same character when he did the lead in The Thing … and would go on to reprise it a third time in It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955, review).

We quickly move back to the States, where it turns out nobody believes Nesbitt’s story of a giant monster, and he is forced to talk to a shrink (King Donovan from The Magnetic Monster [1952, review] and Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1956, review]), who tells him his brain has simply short-circuited from the stress. In the meantime, we catch up with our Beast, who proceeds to sink a Canadian trawler. Back to Nesbitt, who next consults Professor Thurgood Elson (a brilliant, brilliant Cecil Kellaway), a kind and whimsical professor, just about to go on his first holiday in 13 years. Nesbitt posits that the prehistoric creature would have been thawed out of the ice by the blast, and come back to life. Elson politely informs Nesbitt that he is a complete loony, but his assistant, the beautiful young Lee Hunter (Paula Raymond) thinks there may be something to his story, because Nesbitt has written such a brilliant paper on radioactive isotopes, and ”he seemed so sincere”.

Meanwhile, the Beast wrecks a lighthouse in one of the film’s most iconic scenes, and the one scene that justifies the ”Inspired by a story by Ray Bradbury” credit. Then we go on to some character development, where Lee shows Nesbitt drawings of dinosaurs, hoping he might recognise the monster he saw. Take note that we here have a female character that is more than just window-dressing. She also serves coffee and sandwiches, naturally. The scene with the two politely flirting with each other over the dinosaur pitcures is actually rather enjoyable, as it has a very laid-back and natural feel about it, absent from many films of the decade, with Nesbitt slouching on the floor next to a sofa, with Lee in the sofa, precariously brushing her (fully covered) knee agains his shoulder, which would have seemed rather racy at the time. Unfortunately it is also interpunctuated with really bad jokes about her as a palaentoligist and representing the past, him being a nuclear scientist, representing the future. ”Well, let’s get back to the present”, she interjects as a kiss hangs in the air. Another cringe-worthy line is ”I make coffee strong enough to enter the Olympics.” I had to rewind to make sure I didn’t mishear it. Someone actually wrote that line? Finally Nesbitt finds what he is looking for: it is a rhedosaurus, Lee informs him. No, don’t bother googling, it doesn’t exist (didn’t exist). There may be some half-clever word-play going on as ”rhed” means ”in reserve” or ”backup-” in Latin. This is literally the backup dino, when all actual critters failed to live up to Harryhausen’s vision.

We then veer off to find the Canadian captain of the sunken trawler, which takes up a good deal of time, only to have him refuse to testify about the ”sea serpent” he claims to have seen (10 minutes of padding done right there, and Swiss Hubschmid gets to showcase his fluent French), but his first mate (Jack Pennick) picks out the same dino as Nesbitt did, making a real case for the existence of the monster. Lee and Nesbitt are able to convince Dr. Elson, who in turn convinces Colonel Evans, who seems to be in charge of both nuclear explosions and defence against prehistoric monsters. One might think he would have risen in rank to general by now. Elson noted that attacks at lighthouses and ships have been made along the east coast of USA from north to south, and this being a rhedosaurus, the thing is probably on its way to its place of birth at the Hudson river (that’s where fossils have been found). With the help of Evans, Elson sets out to find the thing in a diving bell, and promptly gets eaten while enthusiastically describing the beast to Lee over the radio. Cue short sequence of sadness and reminiscing over his silly walk and the way he would give his specimens pet names.

Then begins the final fifteen minutes of the film, the ones it is remembered for – the Beast climbs ashore on Manhattan and starts wreaking havoc. Colonel Evans takes charge of the defence of New York City, because he is apparently the most bad-ass man in the military and is not only expert on nuclear bombs and sea monsters, but also on urban warfare and disasters. As his adviser he gets Dr. Nesbitt, because a man who studies nuclear isotopes is exactly the guy you need for strategy when fighting a 100-foot prehistoric monster. Actually the scenes of the military stalking the wounded beast in a desolated New York are quite eerie and very effective. Of course conventional weapons have nothing on the Beast, and to make matters worse, it also spreads some kind of radioactive disease (conveniently discovered five minutes before the film’s ending). Evans’ strategy to hire Nesbitt as adviser pays off, when he suggests firing a rare nuclear isotope into an open wound of the Beast – thus destroying it from the inside, and preventing the radioactive germs from spreading in the wind. Quickly the isotope is loaded into a grenade, and given to the army’s best rifle man, which actually turns out to be none other than a young Lee Van Cleef, of later spaghetti western fame. However, to get a good shot, he must climb a rollercoaster, along with Nesbitt carrying the isotope in a lead-lined box, leading to the suspenseful last scene of the movie.

The movie is, as mentioned, ”suggested by” a story by lauded sci-fi author Ray Bradbury. Bradbury had written a story called The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms for The Saturday Evening Post in 1951. It is a beautiful and sad little tale of two lighthouse keepers who observe that each year in the autumn, when they start blowing their fog horn, an ancient creature (described much like a brontosaurus) comes to pay a visit. The creature, perhaps the last of his kind, thinks the horn is the call of a female of his species, and lonesome and love-lorn, he comes looking for love, but each time returns down-beaten, as the lighthouse stubbornly refuses to give in to his amorous calls. At last, one year, the creature becomes so angry at this taunting that wakes him from his sleep and gets his hopes up every year, that he promptly destroys the lighthouse.

Whether or not this little story inspired one of the five screenwriters to write the scene where the Beast topples the lighthouse is not known. What is known is that the screenplay was more or less finished, when producer Jack Dietz brought it to Ray Bradbury and asked if he was interested in doing a re-write, perhaps hoping to gain some extra push for the movie by adding the up-and-coming author’s name to the roster. Bradbury was already one of the hottest tickets in the sci-fi fields, after having released his Martian Chronicles and his magnum opus, Fahrenheit 451. Bradbury himself was now trying to assert himself as a screenwriter. This was 1952, when he would later write the screenplay for It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), but that film was released earlier, because of the time it took Harryhausen to complete his stop-motion animation. Bradbury wasn’t particularly interested in taking a crack at somebody else’s work, which he has rarely done, but he pointed out the similarities between the lighthouse scene and his recently published short story. Sensing a win-win opportunity, Dietz bought the rights to the short story. Thus he got the chance to connect the respected writer’s name to his film, and Bradbury got paid for doing nothing at all, and further advanced his reputation as a screenwriter. The film had another working title, but now took the name of Bradbury’s story. Bradbury later renamed his story The Fog Horn when he anthologised it, as to avoid confusion with the film. The short story in The Saturday Evening Post was accompanied by a drawing by James R. Bingham which Harryhausen replicated in the film.

Legend has it that Mutual Pictures had a hard time finding a director for the movie, and one that had been attached pulled out before the film had gone into production. Eugène Lourié, the assigned production designer, suggested he might take over directing duties, and the producers agreed. Lourié was a respected French (born in present-day Ukraine) designer, who had worked with directors like Jean Renoir, René Clair and Charlie Chaplin, and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was his first directorial effort. He got some other directorial work on TV, but is best known for his monster films – the others he directed were Colossus of New York (1958, review), as well as two British productions, Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review) and Gorgo (1961). After this he quit directing, as he was tired of only getting offered monster films. However, he had a long and successful career as production designer, art director, special effects creator and sometimes even writer, producer and actor. He was nominated for an Oscar for his special effects on the disaster film Krakatoa: East of Java (1968). He also did the art direction and special effects on Crack in the World (1965).

The script is a combination of novel ideas and old clichés. The idea of wakening a monster through a nuclear explosion was a stroke of genius and a now a well-worn trope. On the other hand, horror and sci-fi films through the ages have revolved around a central character trying to convince the rest of the world of some menace that others refuse to see, which is what Nesbitt does throughout most of the film, and the idea of the giant monster loose in the city is a clean ripoff off King Kong, even if the destruction rendered is on an unprecedented scale. I do like how the monster is used as a metaphor for nuclear power, or the nuclear bomb, with its blood being poisonous and threatening to infect the entire city. At the time, there was much anxiety about the US government’s nuclear tests, and, prophetically, a year before the catastrophic Operation Bravo at the Bikini atolls, which partly inspired the film Gojira/Godzilla (1954, review). Although an even bigger inspiration for that classic movie The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms itself. While Gojira carried it off much better, you can see the inspiration for its touching hospital scene with the radioactive victims in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, where the army doctor tends to his poisoned patients. There’s also a foreboding in the beginning of the movie, as one scientist says that every time a nuclear test goes off, he feels as if he is at the beginning of a new Genesis, to which Nesbitt replies that he is afraid they instead be closing the chapter of the old one. Still, this is first and foremost a giant monster film made to entertain the masses, and unfortunately never delves very deeply into the nuclear metaphor. And surely it does lose its poignancy somehow at the end, when it is actually a nuclear device that kills the beast.

All in all, this is one of the better written American SF movies of the fifties. It does drag in the middle, and there’s a feeling we’re seeing some padding here and there to get it up to a running time of 80 minutes, but on the other hand, the action and monster sequences are quite nicely distributed, so monster fans don’t need to go too long without seeing a giant dinosaur wrecking one thing or another. The dialogue makes sense most of the time, and people generally behave more or less as normal people. The characters are fairly well written, and for once the hero is actually sympathetic, and the heroine doesn’t scream, trip over her own feet or faint. In fact, even the military listens to her advice as a scientist. Unfortunately there’s the obligatory “what’s a beautiful girl like you doing examining old dinosaur bones?” That’s coming from the guy who studies isotopes for a living.

Despite the fact that the film doesn’t offer that very much in the way of food for thought, and sometimes feels a little plodding, it never feels overtly slow or boring, but is thoroughly entertaining all the way through. The film never tries to be more solemn that it is, and throws in a bunch of off-hand remarks and jokes here and there. The world hangs in the balance, but it is only a movie, and a B popcorn reel at that, and the filmmakers know it. The lightness is partly thanks to Cecil Kellaway, who does an absolutely wonderful job as Professor Elson, and is thoroughly enjoying himself. What a loveable character!

The star of the film is naturally Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation. As mentioned, this was Harryhausen’s first film in charge of special effects. He didn’t invent the puppeteering technique, but picked it up after seeing pioneer Willis O’Brien’s work on The Lost World and King Kong. Harryhausen made his first short stop-motion film in college in the early forties, and sent the unfinished movie to George Pal, who at the time was known as a master animator, rather than a visionary sci-fi producer. Pal was so impressed that he hired Harryhausen as an animator on his popular Puppetoon children’s short films. Harryhausen continued with these films up until 1952. In between he also got hired by his idol Willis O’Brien to work on the pseudo-sequel to King Kong, Mighty Joe Young (1949), which earned O’Brien an Oscar, although Harryhausen did most of the animation on the movie.

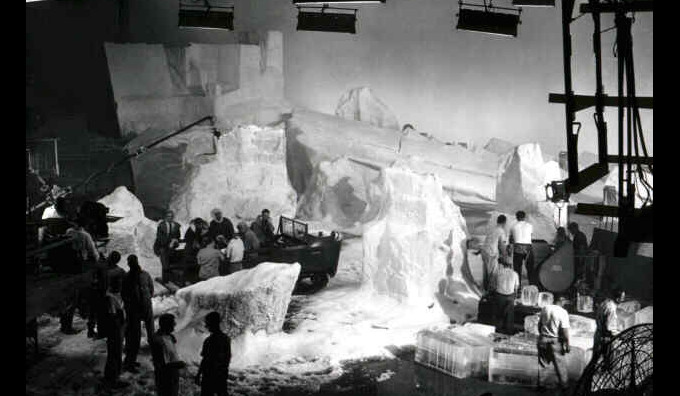

The problem with stop-motion animation has always been that it is an extremely time-consuming process – and that’s not only because the puppets themselves have to be so carefully adjusted. There was also the question of combining the puppets with the actors – and make it all look real and three-dimensional. What Willis O’Brien had done to create this effect was sandwich the puppets between painstakingly painted glass mattes and rear-screen projection of the actors. But since The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was a low-budget movie made for only 210 000 dollars – less that It Came from Outer Space with its rubber aliens, for example, the producers simply couldn’t afford to hire him for the length of time it took to paint and adjust all the glass mattes. So Harryhausen had to think of something new. What he did, was that he learned from other special effects people how to film so-called travelling mattes – or what we today refer to as blue- or green-screen. Once he had that down, he could replace the glass mattes with travelling mattes that gave the same depth-illusion, but had the added benefit that he could use live-action film or photographs. This meant that he could do his work much faster, but it still took half a year for him to conclude the effects on movie. He dubbed the process “Dynamation”, and used it in all his subsequent films.

The lesson he learned from O’Brien was the importance of giving the puppets character and personality – intelligence, if you will. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is perhaps not the prime example of this, but the again, we are dealing with a dinosaur and not a Cyclops. Still, the Beast isn’t merely a killing machine, as many other movie monsters tend to be, but has its little quirks and is clearly interested in the new world he is exploring, which is what makes him so interesting to watch. It’s not Harryhausen’s best work, and there are sequences where the animation is rather jerky. But in some instances you almost believe that what you are seeing is a real live dinosaur from the deep.

The acting in the film often receives some flack, and surely there are no Oscar-worthy performances in it. But overall I find that the acting is quite decent. Swiss Paul Hubschmid’s accent is all over the place, but I find it quite refreshing to have an accented actor as a heroic lead, which you don’t see that often in films like this. Of course, they could have named his character Hans Zimmer or something, instead of Tom Nesbitt, since no-one buys that he is American or British. But if it worked for Schwarzenegger, then why not for Hubschmid … In fact, Hubschmid comes off as one of the more nuanced of the many buff leading men in the Hollywood B movies of the day, which should come as no surprise as he had a solid theatrical and cinematic background, having acted on stage and in film in Germany since the thirties.

Paula Raymond’s part is unfortunately not very well written, and she gets most of the cringeworthy lines of the movie, like the coffee fit to enter the Olympics, and ”I have a deeply abiding faith in science. Otherwise I wouldn’t have become a scientist”. Raymond seems as if she is not quite sure how seriously to take the role, and comes off as one of the weaker links in the movie. Kenneth Tobey is steady in his signature role, as mentioned earlier.

The movie looks stunning, if you consider it was made on 210 000 dollars. In today’s money, that’s 1,5 million dollars, which is basically the budget for a straight-to-DVD film or a really expensive film made in Lithuania. Harryhausen cleverly drops the Beast in front of photographic mattes of New York, and does a great job with the miniature city that the thing rampages through, and it is very well matched by Lourié’s live-action footage and special effects. The movie is shot by John L. Russell who did such a great job with Edgar G. Ulmer on The Man from Planet X, and less so on Invasion U.S.A., The Atomic Kid (1954, review), Tobor the Great (1954, review) and Indestructible Man (review). His great claim to fame is shooting Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Credit should also be given to Oscar-nominated Bernard W. Burton for matching the live-action shots and the animation shots together. He also co-produced with Dietz and Hal E. Chester.

This was without doubt the best film that Jack Dietz ever produced, as he was known for producing low-budget programmers with Bela Lugosi at Monogram, like The Corpse Vanishes (1942), The Ape Man (1943, review), The Return of the Ape Man (1944) and the hilarious Voodoo Man (1944, review). He went on to produce two more films, including The Black Scorpion (1957, review). Dietz made quite a killing on The Beast, as it went on to gross 5 million dollars in the US alone.

While made on the cheap, Warner gave The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms a costly marketing campaign and the fastest and widest release of almost any movie up to that date. It opened in over 1,400 theatres in its first week. It became an instant classic, and revitalised the giant monster genre, most importantly inspiring Ishiro Honda and Toho Studios to make Gojira in 1954. The press have it mixed-to-positive reviews. A.H. Weiler at the New York Times was not much impressed with the story itself, finding it unrealistic, filled with pseudo-scientific jargon and somewhat talky. However, he did give credit to Harryhausen for the “nightmarishly photogenic, king-sized destroyer”, and noted that “it generates a fair portion of interest and climactic excitement as the beast […] makes its way down from Baffin Bay”. Variety took a more positive stance, writing: “Producers have created a prehistoric monster that makes Kong seem like a chimpanzee. It’s a gigantic amphibious beast that towers above some of New York’s highest buildings. The sight of the beast stalking through Gotham’s downtown streets is awesome. Special credit should go to Ray Harryhausen for the socko technical effects”. Clyde Gilmour at Canadian Maclean’s Magazine called it “a naive but entertaining fantasy”.

Hollis Alpert at the Saturday Review also noted that “Warner Brothers has not been too masterful with its screenplay, but they has allowed their special effects craftsmen to have a field day”. Our Culture Mag gave the movie a positive 3.5/5 star review, and genre magazine Startling Stories was likewise encouraging, giving the film a two-page review. Unlike most film critics, Pat Jones had actually read Ray Bradbury’s original story, and notes that little of it is to find in the script: “Expanded into movie script length, it’s impossible to retain any of the poetic poignancy of the original, but it does provide top entertainment. […] This was a well-paced, expertly directed picture with a better than average script and excellent performances”.

In his seminal 1970 book Science Fiction in the Cinema, John Baxter noted that while director Lourié was a Frenchman, the film was “spectacularly American in its ambience and approachm but Lourié still managed to instill into it some of his expertise and feeling for mood”. Baxter complains about the “sketchy script” and “unintentional humour”, and says that the film “is only really at its best when Lourié and effects man Ray Harryhausen are allowed full charge”.

Today The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms regularly shows up on lists of the greatest monster and SF movies of all times, albeit never quite at the top of the list. Its 6.7/10 rating on IMDb shows that it has a mixed reputation among audiences, although it has a very solid 95% approval rating by critics at Rotten Tomatoes. AllMovie gives it a decent 3/5 star review , with Craig Butler writing: “It’s been done countless times, and so Beast isn’t as fresh as it was in 1953; but the film still has an air of simplicity and innocence about its plotting that is rather beguiling. It’s all nonsense, of course, but it good clean fun nonsense, and it still is quite engaging.” TV Guide writes: “Not a bad monster film […] Lots of good monster sequences overshadow any acting in the movie”. Kim Newman at Empire magazine likewise goes with a 3/5 star review, calling the Beast “one of the greatest dinosaurs in the movies”. Luke Spafford at Starburst magazine gives it 7/10 stars, writing: “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms provides an ample, if not slightly stodgy, slice of B-movie pie that’s improved by the sprinkling of Harryhausen’s cream on top. A forerunner to Godzilla it may be, but there’s a reason only one of the two spawned what seems like a thousand sequels.” And Christopher Stewardson at OurCulture Mag gives it 3.5/5 stars: “Despite its shortcomings with its simple story and basic character dynamics, the film is elevated to brilliance through its camera work, production design, rousing musical score, and masterful effects work.”

In his book Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren writes: “Had the same storyline been entrusted to another director, and had the special effects been done less well, [Beast] would have been a below-average monster picture. As it is, the atmospheric, intelligent direction, and the vigorous, exciting animation overcome the talky script to create a lively addition to the short list of good monster-on-the-run films.” Chris Barsanti notes in The Sci-Fi Movie Guide that the film isn’t one of Harryhausen’s best, but still “suspenseful, solidly constructed and tons of fun to watch”. Clive Davies in Spinegrinder calls it “not very good”, apart from Harryhausen’s work.

My go-to internet critics continue among the same mixed lines. Richard Scheib at Moria awards The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms only 2.5/5 stars: “The film itself is slow moving and Eugene Lourie’s direction literal-minded. The film does pick up in the last quarter in the moody scenes with the military defending the city and the tense Coney Island climax.” Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant calls it ” an endearingly simpleminded but visually impressive monster movie”.

I like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. But it is talky, and does drag its feet in the middle. The characters are all bland, with the exception of the dotty scientist. The dialogue is OK, but does have some cringe-moments. This is not Harryhausen’s most proud moment, but considering he was working out a new way of doing stop-motion filming on the fly, and had almost no time to do it, the result is exhilarating. The model of the rhedosaur is one of the lesser puppets he worked on — it’s a bit rubbery and doesn’t have as much personality as many of his later creations. However, this doesn’t matter much, as Harryhausen brings his trademark magic to the screen. In 1953 the monster was the most impressive thing seen on screen since King Kong. The creature’s rampage through New York is absolutely riveting, and well worth waiting for. It crushes cars and tosses them in the air as if they were pillows, bursts through buildings, tramples bystanders and eats a poor policeman in one of the great shots of the movie. One gaffe is that the monster seems to change in size throughout the film. At one point his head is about the size of a car, but in the policeman-eating scene, the poor guy looks like a tooth-pick, as one reviewer pointed out.

Kenneth Tobey, who played second fiddle to Paul Hubschmid in the movie, was already a bona fide SF star, thanks to his memorable turn as the hero of The Thing from Another World. In an interview with Tom Weaver in Double Creature Feature Attack, he recalls that he enjoyed working on The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms very much: “I also met Ray Harryhausen […] and I’m very, very proud of that moment. He was extremely witty and very well trained in his profession.”

Director Eugène Lourié also tells Weaver he was signed to the picture by the producers when all they had was a short story outline. The Arctic scenes, he says, where shot on set, and the amusement park finale at Long Beach. The crowd scenes were partly shot in New York, and partly at Paramount’s back lot New York sets. When they looked at some of the extras that turned up in New York as stevedores for the fish market scene, they realised they were too small to be stevedores, so they went out and hired real stevedores to appear in the movie. When shooting crowds at Wall Street they only got 25 extras instead of 50, because it was a Sunday and the studio had to pay double for Sunday work. According to Lourié, it was producer Hal Chester who brought in Ray Harryhausen (although other sources claim it was Dietz), who was making fairy-tale shorts for children at the time. Says Lourié: “I was amazed at how long it took, the frame-by-frame animation. The time it took to shoot the picture was 12 days; to animate it, it took two or three months! But I enjoyed working with Harryhausen very much.

According to Lourié, the producers had originally envisioned the film as a small cash-in released through various small distributors, but when they saw the quality of the finished movie, they decided to try and talk Jack Warner into distributing it. But Warner didn’t want to distribute it — he wanted to buy it. Lourié says Warner Bros. bought the film for 450,000 dollars, over double its production costs, which producer Jack Dietz thought was a great offer. Then when it went on to earn over 2 million dollars at the box office, “Dietz was very unhappy […] Every time he read about it in Variety, he said ‘Oh I am stupid’”.

In an interview with both Ray Harryhausen and Ray Bradbury on a 2003 DVD release, the two Rays say that Jack Dietz had originally seen Bradbury’s short story The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in The Saturday Evening Post, where it had originally appeared, and mentioned to Harryhausen that it could make for a good basis of a film. Harryhausen was at the time a good friend of Bradbury’s, and was happy to start developing ideas, as the two had talked about doing a movie together. At the time, apparently, Dietz hadn’t noticed that the story was written by Bradbury, and by coincidence, he later handed the working script, titled “The Monster from Beneath the Sea” to Bradbury, asking if he would be willing to do a rewrite. Bradbury was surprised to find similarities between his story and the script, and mentioned this to an even more surprised Dietz. A few days later, Bradbury received a telegram from Dietz, who offered to buy the story, and this is probably the point when the film changed name from “The Monster from Beneath the Sea” to The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. And as stated, when Bradbury included the story in his influential short-story collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, released just a few months before the film was released, he re-titled it The Fog Horn.

Primary credited screenwriters were Lou Morheim and Fred Freiberger. Freiberger also co-wrote the 1957 film Beginning of the End (review) and a number of other films, but found his true career in TV, where he became a prolific writer and producer. He wrote and/or produced several episodes for The Wild Wild West (1965), Josie and the Pussy Cats in Outer Space (1972), Super Friends (1973), The Six Million Dollar Man (1977-1978) and Superboy (1988-1989). He also wrote and produced two sci-fi TV movies and was principle producer on the TV series Space: 1999 (1975) and Beyond Westworld (1980). He is probably best remembered, however, as producer of the third and final season of the original Star Trek series (1968-1969), taking over from Gene Roddenberry. Debate has raged over his talents as a producer, since four of the sci-fi series he produced were cancelled during his watch – apart from Star Trek, they were Josie and the Pussy Cats in Outer Space, The Six Million Dollar Man and Space: 1999. But actors Nichelle Nicholls and William Shatner of Star Trek have both defended Freiberger, claiming he did what he could – and well – with a series that NBC had decided was going out anyway. Some sci-fi fans still refer to him as ”the series killer”, while others point out that Freiberger on all the three major shows stepped in to try and save series that were already in big trouble. The animated Josie and the Pussy Cats in Outer Space was a spin-off of Josie and the Pussy Cats, and was Freiberger’s own idea, and was probably never meant to run for more than one season.

Lou Morheim initially had a similar career trajectory as Freiberger. He started out writing scripts for films, but soon found himself as writer and producer for TV shows. He is perhaps best known for co-scripting the films The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Hunting Party (1971), as well as for producing the hit western series The Big Valley (1965-1969). He also worked as a writer and producer on the TV shows The Outer Limits (1965) and The Immortal (1975).

Screenwriting credit for The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was also given to Lourié, Daniel James and Robert Smith. James worked only on four films, all of them with Lourié – he also co-wrote Behemoth the Sea Monster and Gorgo. Robert Smith this blog already knows as the producer of the abysmal Invasion U.S.A. (1952, review), which he also wrote. He also wrote for the TV series Science Fiction Theatre (1955-1957) and Sea Hunt (1958-1961), although why anyone would give him a job in Hollywood after Invasion U.S.A. is beyond me.

Ray Harryhausen is best known for his fantastic work in the fantasy epics based on Greek mythology, such as The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and Clash of the Titans (1981), but he got his start in science fiction. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was followed by It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review) and 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review). Much of his later work was produced by Charles Schneer, who also indulged Harryhausen his wish to co-create one of his pet projects, an adaptation of H.G. Wells’ First Men in the Moon (1964). The dinosaur movie The Valley of Gwangi isn’t his best film, and is one of those that some would call sci-fi, but which I call fantasy. His best known film outside the mythological movies is probably One Million Years B.C., which is a film that is probably watched by creationists as a documentary. To be fair, the film is probably better known for Raquel Welch’s minimal bikini than for Harryhausen’s dinosaurs, but some claim that the movie contains some of his best animation. One should point out perhaps, that even though we speak of Harryhausen films, he didn’t direct a single full-length feature film, he did co-produce many of them, however.

We have already encountered dotty professor Cecil Kellaway in The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review), where I described his portrayal of the knowing police officer pursuing said invisible menace as ”superb”. I also wrote that he was ”a South African stage actor who got lured from Australia to Hollywood in the early thirties, and after a decade of doing mostly comedic characters in B-films, rose to fame as a sought-after character actor, and was nominated for two Oscars for supporting roles in The Luck of the Irish (1948) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967)”. He also appeared in Destination Space (1959), as well as the TV-series The Twilight Zone (1959). He was offered the role of Kris Kringle in the Christmas classic Miracle on 34th Street (1947), but turned it down. Instead it went to his cousin Edmund Gwenn, who won an Oscar for it.

Lead actor Paul Hubschmid moved to Hollywood in 1948, and acted mostly in B movies, under the name Paul Christian. He had one of the leads opposite Maureen O’Hara and Vincent Price in Bagdad (1949) and another lead opposite Viveca Lindfors in Don Siegel’s No Time for Flowers (1952). He returned to Germany in 1953, and appeared both on stage and in film, although few of his German films of this era reached an international audience. He continued to make international movies, and in 1958 starred in his only other sci-fi film, the Italo-US exploitation movie The Day the Sky Exploded (review). In 1959 he starred in two popular German historical adventure romances directed by Fritz Lang, The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Tomb of Love. The films were mangled and re-edited into a single 90 minutes long feature called Journey to the Lost City in USA. He appeared alongside Michael Caine, Oskar Homolka and his wife Eva Renzi in the German-British production Funeral in Berlin (1966) and the American WWII movie In Enemy Country (1968). He had the dubious honour of starring alongside Burt Reynolds in the missing bad link movie Skullduggery in 1970. Hubschmid practically retired in 1975, but still appeared sporadically in film and on TV until 1992. He passed away in 2001, 84 years old.

Paula Raymond was a fairly sought-after actress for B movies in Hollywood, and was even poised for bigger success at one time. After a string of bit-parts in the late forties, she was picked up by MGM as a leading lady, first opposite Cary Grant in Crisis (1950), then Devil’s Doorway (1950) with Robert Taylor, and The Tall Target (1951) with Dick Powell. However, her roles got smaller, and she was let go from MGM in 1952, and found herself appearing as leading lady again, but now in B movies. She quickly transitioned to TV, briefly left the business in 1955 only to return in 1958, and her career started to pick up again in 1959 with a good number of guest spots on successful shows. But her career was interrupted by a car accident, which nearly tore off her nose, which required a year of plastic surgery to mend. She was back to acting in 1962, but her career never really took off after that. A broken ankle torpedoed what would have been a regular role on Days of Our Lives, her second missed opportunity after she had turned down a role in Gunsmoke in 1952. Her last credited acting roles (according to IMDb) were the no-budget horror films Five Bloody Graves and Blood of Dracula’s Castle (both 1969), starring John Carradine and Robert Dix. She had a bit-part in the 1994 mystery thriller Mind Twister. Alledgedly a fall in 1984 in which she broke both her hips hindered her career, but on the other hand, she hadn’t had much of a career since 1962, and it was unlikely to pick up tremendously after her 60th birthday.

Western legend Lee Van Cleef probably doesn’t need any introduction. Many might not know, though, that at the same time that he made his film debut in High Noon (1952), he also appeared in a number of episodes of the kiddie show Space Patrol, the main rival of Captain Video and His Video Rangers (review). In 1956 he appeared in Roger Corman’s sci-fi movie It Conquered the World (review), in one of the leads, and made a guest appearance on The Twilight Zone in 1961. He is also remembered by sci-fi fans as Hauk, the man who sends Kurt Russell’s Snake Plissken into New York in John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981).

The movie is filled with an impressive cast of B film foot soldiers, and it would take forever to name all that should be named. But let’s pick out a few. Steve Brodie (as another military type) played the ill-fated reporter Herbie Yokum in Donovan’s Brain (1953), appeared in a couple of episodes of Science Fiction Theatre (1955), and appeared in three of the worst sci-fi films ever made. He had a starring role in the sci-fi comedy The Wild World of Batwoman, that holds the place of the 40th worst film in history on IMDb. He played on of the leads in The Giant Spider Invasion (1975), and had another leading role in the truly awful Frankenstein Island (1981). He sort of made up for it in a role in the low-budget fireworks that was The Wizard of Speed and Time in 1988. Ross Elliott appeared as the male “lead” in Carolina Cannonball (1955, review), and provided support in Tarantula (1955, review), Indestructible Man (1956, review), Monster on the Campus (1958, review), The Crawling Hand (1963) and a whole bunch of sci-fi TV shows.

Paula Hill who plays some character called Miss Ryan’s claim to fame is that she played the female lead in the cringy patchwork Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review). Michael Fox as the ER doctor appeared earlier the same year in The Magnetic Monster (review), and went on to appear in the other two Ivan Tors films about the Office of Scientific Investigation: Gog (1954, review) and Riders to the Stars (1954, review). He also appeared in Conquest of Space (1955, review), War of the Satellites (1958, review) and The Misadventures of Merlin Jones (1964), as well as a number of TV series. Fox doubled as dialogue director on The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The above mentioned King Donovan’s greatest claim to fame is playing one of the leads in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but also appeared in The Magnetic Monster and Riders to the Stars. Prolific character actor and acting coach James Best is best known for his role as Sheriff Roscoe Coltrane in The Dukes of Hazzard (1979-1985). He had bit-parts in Riders to the Stars and Forbidden Planet (1956, review), as well as starring roles in a number of episodes of The Twilight Zone (1962-1963). Some fan at IMDb has written that The Dukes of Hazzard was ”far below his talents”, but that writer should have taken a better look at his resumé and found out that he also played the lead in The Killer Shrews (1959) and The Brain Machine (1977), and I’m not sure how much lower you can go.

In a tiny bit-part as deckhand we find Robert Easton, renowned character actor and a dialect coach in Hollywood. Easton provided the voice for one of the leads in the SF marionette series Stingray (1964-1965), had a starring role in The Giant Spider Invasion, played the Klingon Judge in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991), appeared in Storybook (1996) and had one of the leads in Spiritual Warriors (2007). He worked as a dialogue coach on a number of high-profile movies, including Al Pacino’s Scarface (1981), Good Will Hunting (1997), and The Last King of Scotland, where he worked, among others, with Forest Whitaker, who won both an Oscar and a Golden Globe for his portrait of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin. Healso worked with actors like Arnold Schwarzenegger (not entirely successfully, it would seem), Charlton Heston, Liam Neeson and Anne Hathaway, among others. Easton passed away in 2011. In an obit The Boston Globe writes that Easton started paying attention to speech patterns to tackle a stutter as a child, and started learning accents when he feared getting typecast as a dumb southerner. In later years he was instantly recognisable for his long, white hair and white, wizard-like beard.

Other notable bit-part actors include Roy Engel (see my review of The Man from Planet X, 1951), Joe Gray, who appeared in The War of the Worlds (1953, review), a number of James Bond-inspired comedies with agents Flint and Matt Helm, as well as Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) – and the actor that appears in about one third of the films I review, Franklyn Farnum, always there, always uncredited. One of the stuntmen on the film is legendary Gil Perkins, who, among other things, doubled for Bela Lugosi as the Frankenstein monster in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943, review). Perkins also had a number of speaking roles, some of them rather big.

Janne Wass

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. 1953, USA. Directed by Eugène Lourié. Written by Lou Morheim, Fred Freiberger, Daniel James, Eugène Lourié, Robert Smith. Suggested by the short story The Fog Horn by Ray Bradbury (although not really). Starring: Paul Hubschmid, Paula Raymond, Cecil Kellaway, Kenneth Tobey, Donald Woods, Lee Van Cleef, Steve Brodie, Ross Elliott, Jack Pennick, Ray Hyke, Paula Hill, Michael Fox, Alvin Greenman, Frank Ferguson, King Donovan, Merv Griffin, James Best, Robert Easton, Franklyn Farnum, Roy Engel. Music: David Buttolph. Cinematography: John L. Russell. Editing: Bernard W. Burton. Production design: Eugène Lourié. Set decoration: Edward G. Boyle. Makeup artist: Louis Phillipi. Special effects: Willis Cook, Ray Harryhausen: George Lofgren, Eugène Lourié. Visual effects & animation: Ray Harryhausen. Produced by Jack Dietz for Mutual Pictures of California & Warner Bros.

Leave a comment