∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗

(8/10) A huge success upon its release, this German 1916 6-part epic film series follows the exploits of the soulless supervillain Homunculus, a creature created by science, as he wows to find love or destroy humanity. Robert Reinert’s multi-layered script draws on Frankenstein and Faust, as well as Freud, Nietzsche and Marx to create both a treatise on the human condition as well as a comment on WWI. While scarcely shown outside Germany before 1920, it turned lead actor Olaf Fønss into a matinée idol and even influenced fashion.

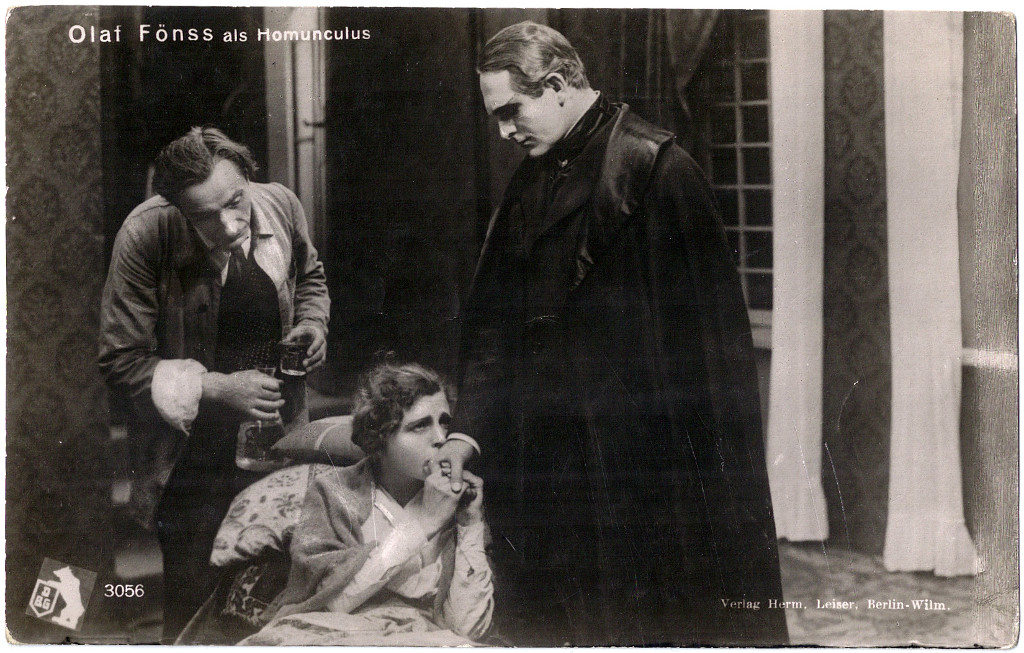

Homunculus. 1916, Germany. Directed by Otto Rippert. Written by Robert Reinert. Starring: Olaf Fønss, Friedrich Kühne. Ernst Ludwig, Albert Paul, Max Ruhbeck, Theodor Loos, Aud Egede-Nissen, Mechthild Thein, Maria Calmi, Lupu Pick, Gustaf von Wangenheim. Produced by Hanns Lippmann. IMDb score: 7.1. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metascore: N/A.

In 1916 World War I raged across Europe. In the centre of the tragedy stood Germany, a country hat had been rattling its nationalist sabre since Emperor Wilhelm II came to power in 1888. Germany’s film industry suffered the same fate as all European film industries during the war, as funding for the arts was deemed of lesser importance. However, the German movie scene, closely linked to the Danish one, remained surprisingly vital artistically, despite the war. Or perhaps even because of the war.

As Britain, Russia, France, Italy and to a lesser degree the United States all ganged up on Germany and Austria-Hungary, Germany banned all films produced in the allied countries. Considering what the power structure in the field of film looked like at that point in time, that basically left German and Danish films. So while public funding for German films was tight, there was a huge demand for new German movies. This sudden increase in demand meant that German film production suddenly flourished – the number of films produced in Germany rose from 24 in 1914 to 130 in 1918.

And with powerful movements and developments in society, politics, science and culture, many of the German films of the era were artistically ambitious, experimental and often dark as the times they were made in. While the war helped establish the US as the dominant force within the international film industry, it also paradoxically turned Germany into the second most influential movie producer in the era between the two world wars, establishing both the cinematic language for horror films and the German Expressionism, a style of filmmaking that echoes even in movies made today.

While the starting point for German Expressionism is often considered to be Robert Wiene’s 1920 masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, there were numerous films before that pointing the way, starting with Paul Wegener’s Faustian The Student of Prague (1913) and his monster movie The Golem (1915). Important milestones were also Richard Oswald’s sci-fi-coloured dark melodrama The Tales of Hoffmann (1916, review) and Unheimlige Geschichten (1918), generally seen as the blueprint for the horror film. One of the most successful Proto-Expressionist films was Otto Rippert’s film series Homunculus, made and released in 1916.

Homunculus was originally made as a six-part film serial, with each part around an hour in length, totalling six hours of film. The serial was a huge success in Germany, to the point that it even influenced fashion: the black cape and slouch hat worn by Danish lead actor Olaf Fønss became popular with the urban dandy in Germany. Because of the war, the film wasn’t generally released outside Germany, Austria-Hungary and parts of Scandinavia. After the war it was re-edited and condensed into a 3-part serial in 1920. But even though German films were now being widely distributed, Homunculus didn’t get a wide international release this time either. For example Paul Wegener’s own 1920 remake of The Golem was widely distributed in the US, but the contemporary press doesn’t mention Homunculus.

For decades only pieces of the film were available, until the 1920 version of the serial was re-edited and restores from various prints by film historian Stefan Drössler in 2014. Unfortunately this restoration isn’t available on internet in all its 196-minute glory. The film floating around on Youtube is an 80-minute condensation of the film with Italian intertitles, and it is essentially this film that I’m reviewing. Although it may seem as if viewing a film with 120 minutes missing may not be fair, I’m not sure that 120 minutes are actually missing, as the story is basically all there, with a few omissions. My guess is that the Italian print has been digitised at the wrong frame rate, cutting over one third of the running time. From what I can tell there are bits missing at least from chapter 3, chapter 5 seems to be omitted completely and only parts of chapter 6 remains. It is quite enough to create a coherent film out of, even if some characters appear and disappear rather abruptly and there are a few confusing jumps in time.

The film tells the tale of Richard Ortmann/Homunculus (Olaf Fønss), who is not born, but the scientific creation of Professor Ortmann (Ernst Ludwig). Brought up as Ortmann’s natural child, thanks to the old “switch a dead baby for a living in the cradle”-schtick, the young Homunculus grows up to be a young, handsome man, but eternally depressed and frustrated over his inability to feel love and camaraderie. At 25 he discovers the secret of his identity, and sets out into the world with a singular mission: to either discover love or destroy humanity. His only companion is Edgar Rodin (Friedrich Kühne), a scientist and friend of his “father”, who is fascinated by Homunculus, and aids him in his scientific endeavours.

The following four chapters basically have the same premise: in repeated fashion Homunculus finds a woman whom he tries to love, but ends up driving her to kill herself, kills her family or is rejected and hunted as soon as the secret of his identity is revealed. He starts off trying to do good in the world, using his “special abilities” to heal a prince in Africa, but becomes a cynic after he is chased out of the city to chants of “Kill Homunculus! Kill Homunculus!”

On his travels Homunculus meets one woman who refuses to stop loving her fiancé, even after he scorns and rejects her. One father tries to poison him after he learns that his daughter is dating Homunculus but the daughter accidentally drinks the poison instead. Homunculus elopes with an engaged woman, whose ex-boyfriend kills himself in grief, then her mother dies of grief and finally her father passes away. She leaves Homunculus after he has taken everyone she loved from her.

In chapter four, we meet Homunculus after he, together with his companion Rodin, has become the owner of a huge corporation, after Homunculus has been able to create a weapon of mass destruction, a flaming liquid, powerful enough that “one drop will kill millions”. As master capitalist Homunculus wilfully oppresses the workers and the poor, laughing at their demands for justice. But at night he disguises himself as a proletarian agitator, fanning the flames of revolution among the workers. Now he also meets a women who is just as bloodthirsty as he is, and loves him for what he is. But their plans of world war fails when a preacher intervenes, preaching the message of reconciliation to the people. Homunculus girlfriend betrays him and he is thrown in jail, but escapes with the help of Rodin.

In the fifth chapter, omitted from the readily available edit, Homunculus, disappointed in humans, recruits a young couple to live in isolation, bringing up their son on an island, as a new breed of man, uncorrupted by the rest of humanity. Unsurprisingly, this scheme also backfires, leading Rodin to finally abandon Homunculus. The sixth chapter, also heavily cut in the Youtube version, sees Rodin creating a second Homunculus whom he plans to use to destroy the original one. Homunculus is now living as a hermit in a cave, where he wallows in regret and has premonitions of approaching death. A final battle between the two homunculi takes place high up on a mountain top.

Homunculus was the brainchild of Austrian screenwriter Robert Reinert, a moderately successful author who wrote his first scripts in 1915. When he wrote Homunculus for Deutche Bioscop, he was relatively unknown, but the huge success of the films earned him a contract at the studio. He later founded his own short-lived film company, before it was merged into Emelka, and in 1925 he joined the giant UFA, three years before his death. During his career he wrote over 30 films, and directed and produced close to two dozen others. After his success with Homunculus, he was hired by Bioscop mainly to write scripts for Italian actress Maria Carmi, who also has a small role in Homunculus. These films were only moderately successful, and Reinert tried to recapture the magic in his 1917 film trilogy Ahasver, about the mythical Wandering Jew. The film series, which he also directed, borrowed many themes and stylistic traits from Homunculus, and was successful but not nearly as big as its predecessor.

Reinert’s last two successful films came in 1919 with Opium and Nerven (Nerves). Nerven is generally seen as his crowning achievement, a feverish psychological horror drama dealing with Germany’s collective post-traumatic stress syndrome after the ending of WWI. Reinert’s powerful and haunting script and his unusual direction is seen as a strong precursor of German Expressionism. The film drew large crowds initially and was met with rave reviews, but the film was pulled from theatres shortly after the premiere, due to reports of hysterical reactions from audience members in Munich after they had seen the film.

The immediate inspiration for Homunculus surely came from the success of Paul Wegener’s The Golem (1915). In connection with a screening of the restored version at MoMA, The New York Times’ Nicolas Rapold called the film “a sort of mix between Frankenstein and Fritz Lang’s later Metropolis”, and the notion hits pretty close to home, even if it is a bit of a reduction. The parallels to Frankenstein are obvious: like in Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel the film deals with an artificial being who is feared for what he is rather than what he does, and travels the world looking for love. While Homunculus doesn’t explicitly turn on his creator, he does do so metaphorically by turning on humanity. Like Frankenstein, the film can easily be read as a warning about science. The notion of science turning deadly is especially poignant considering the time in which the film was made, as WWI raged with all its modern warfare technology like tanks, planes, machine guns and mustard gas. Homunculus creating a weapon of mass destruction himself is a bit on the nose, though.

An interesting subplot is the one where Homunculus is wilfully creating strife between workers and capitalists, playing at being agitator for both groups at the same time, and deceiving them both in order to create chaos. Interestingly, this exact same plot device was used by Thea von Harbou and Fritz Lang in Metropolis (review). In that 1927 film, a mad scientist creates a female robot in the spitting image of the peaceful and angelic Maria, who seduces the working class into revolting, before turning on them once the class war has broken out.

Themes of doppelgängers, automatons and marionettes were extremely popular with Expressionistic filmmakers, who often laboured with themes of moral duality, Freudian projection and Faustian self-deceit. Homunculus uses his origin, in essence a perceived paternal betrayal, as an excuse for his own evilness. He reasons that because he cannot feel love, he must be evil, and as he is evil, he is not morally responsible for the evil that he does. Evil does as evil is, in essence. But thanks to the strong acting of lead Olaf Fønss, the viewer is rather quickly led to the conclusion that Homunculus’ real problem isn’t really that he feels too little, but rather that he feels too much. Instead of dealing with his feelings of betrayal and rejection, he thrusts the blame of his shortcomings onto his “father” and society for having created him as a monster: laying the blame on society, he refuses to take responsibility for his own actions. In a sense a very modern notion of a morality play.

Danish movie star Olaf Fønss had a strong year in 1916. Already one of Denmark’s biggest names in film acting, he had played the lead in August Blom’s disaster film Atlantis (1913), based on the 1912 sinking of the Titanic, and in 1916 he had a prominent role in Blom’s apocalyptic epic The End of the World (review), the first feature-length apocalypse film. Homunculus made him one of the biggest movie stars in the German-speaking world as well, and he was reportedly paid more for his role than any actor up to that point in a German film.

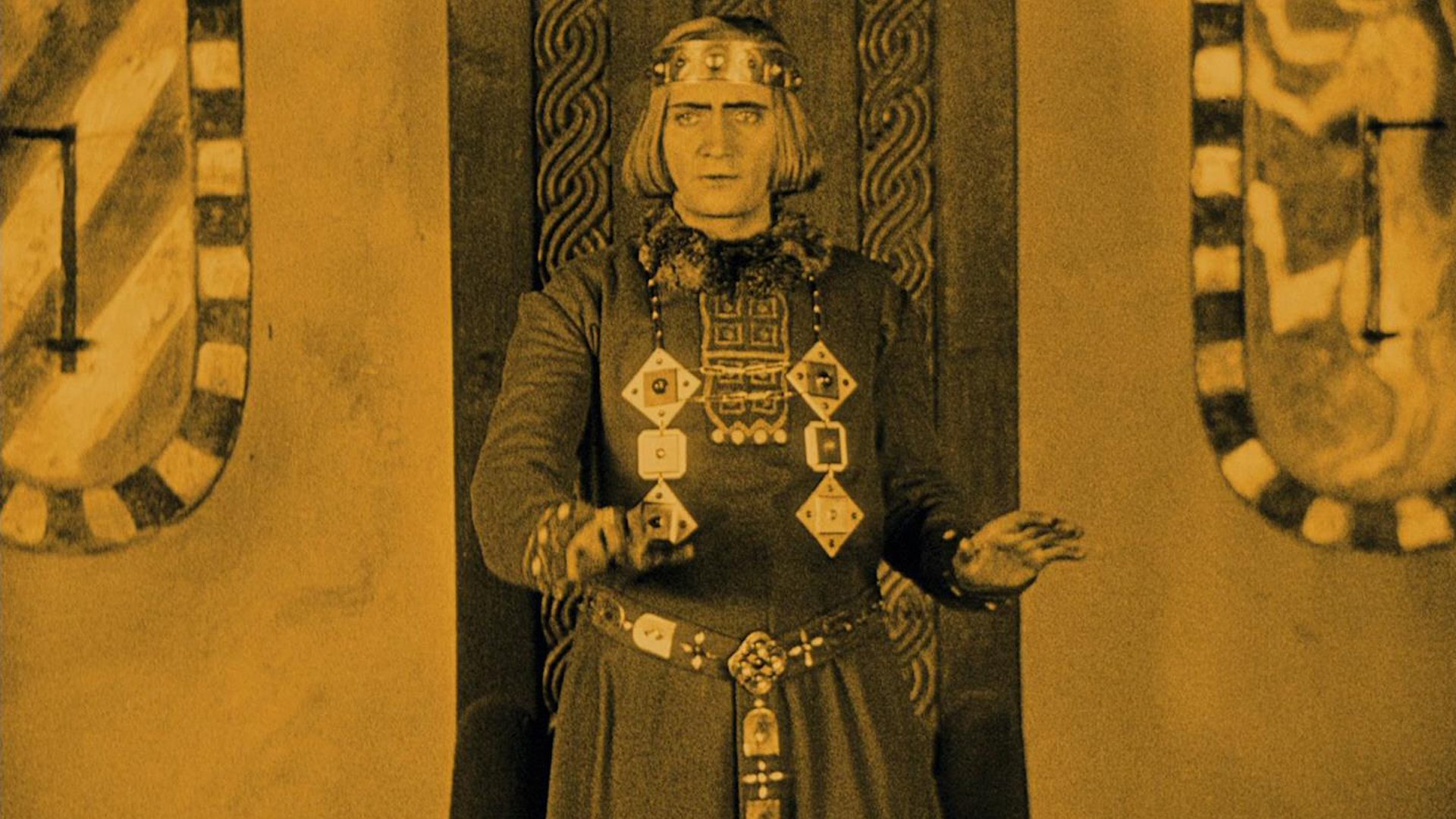

Fønss is magnetic in his portrayal of Homunculus, pulling out all the stops for a wonderfully charismatic and over-the-top performance. This was not his usual acting style, and it stands in stark contrast with his underplayed cool as businessman Frank Stoll in The End of the World. His exaggerated acting technique in Homunculus does break the illusion of reality for a modern viewer, but for an 1916 audience, who was accustomed to this sort of symbolic, rather than realistic, performance, the effect would not have been the same. And while the rest of the actors also announce their performances, none of them do so in the same magnificently grand manner as Fønss: he was not even aiming for realism as Homunculus was not realistic. Homunculus was larger than life. Once you get used to Fønss chewing up all scenery in sight and just go with it, his performance is highly riveting.

Like most Danish screen actors, Fønss also appeared on the stage, and in later years took to film direction as well. He never became a big star of the stage, but instead revelled on the screen. He alternated between Danish and German movies, and after the war he appeared opposite Conrad Veidt in Austrian director Joe May’s 1921 film Mysteries of India, written by none other than Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou. The New York Daily News wrote of the film: “It is astonishing how tiresome a picture can become before the end heaves into sight”. May later directed The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review).

Fønss was a long-time president of the Danish actors union and worked for the national film censor for 14 years. In later years he became heavily involved in politics, supporting the social democrats of Denmark. In 1925 he was sent, “on special commission from the king of Denmark” to the states to study film techniques in Hollywood. According to US newspapers at the time Fønss would have put in a day’s work acting for F.W. Murnau, directing his first American film. If this is indeed the case, then Fønss may be perhaps be spotted as an extra in Murnau’s timeless masterpiece Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927).

Other actors generally pass by too quickly to make much of an impression in the shortened version of the film. Unfortunately this is also true for Friedrich Kühne, playing Rodin. Kühne made a huge impression on me with his Severus Snape-like performance in The Tales of Hoffmann, and what little we see of him in Homonculus is equally strong, Kühne is a charismatic and expressive actor that dominates the screen when he is on. Kühne was already established as a villain in German cinema, and would go on playing sinister roles throughout his career. He played the foil of Sherlock Holmes in a number of movies, including the 1914 version of The Hound of Baskerville, the first feature-length adaptation of the book, Fritz Lang’s The Spiders (1920), Judith Trachtenberg (1920), Othello (1922), The Man on the Comet (1925), Lützow’s Wild Hunt (1927) and Anna Susanna (1953).

Stylistically Homunculus doesn’t show the distorted and surrealistic traits of German Expressionism, but is filmed in a traditional style with static cameras, for the most part labouring with wide and medium shots in an almost tableux-like fashion. But the sets are impressive, making good use of Germany’s state of the art studios in Babelsberg and the environments in Neubabelsberg. There are impressive crowd scenes atmospheric location shots in mountainous and forested locations, as well as impressive and dangerous-looking stunts, not least with stuntmen swimming in huge waves crashing against steep rock faces. There isn’t much in the way of visual effects, but some nice practical effects involving fire and smoke. The film’s influence on Expressionism can be seen mainly in its script and subject-matter, but also in its heavy make-up and the brooding atmosphere, as well as the sharp contrasts between light and shadow.

Some scenes are beautifully framed and shot. The film’s artistic qualities are probably more thanks to cinematographer Carl Hoffmann, who was one of the greats of early German cinema, than to director Otto Rippert. Rippert was well employed between 1910 and 1925, but was never able to renew the success of Homunculus, perhaps with the exception of the dark epic The Plague of Florence (1919). In 1925 he dropped out of directing and began a career as an editor.

The movie is filled with great actors, some of who rose to the crème de la crème of the German film acting community. In a minor role we see Gustav von Wangenheim, a nobleman born into a family of actors, who is something of a legend to friends of old horror films. He started acting in films in 1914, and in 1921 he received the role that he would forever be remembered for, as the male lead Thomas Hutter – or Jonathan Harker – in F.W. Murnau’s genre-making horror classic Nosferatu.

In the 2000 film Shadow of a Vampire, presenting a fictionalised account of the making of the movie, Wangenheim was portrayed by actor and comedian Eddie Izzard. And in 1929 Wangenheim appeared in Fritz Lang’s monumental science fiction movie Woman in the Moon (review). Wangenheim was a devoted Communist and founded a Communist theatre company, Die Truppe ’31, in 1931, which was shut down by the Nazis in 1933. He fled to the Soviet Union where he continued to make German-language anti-Nazi films. In 1936 he was accused of having given up two fellow Germans as Trotskyists, which led to their execution, although there are reasons to suspect that his statement was given under duress and was partly falsified. After WWII Wangenheim moved to East Germany, where he continued his career as screenwriter and director, mainly of propaganda films.

The peaceful preacher who gets Homunculus imprisoned is played by Theodor Loos, one of Germany’s most revered character actors both on stage, in film and in radio. He worked at a number of theatres, including Deutsches Theater under the leadership of the legendary Max Reinhardt, and appeared in over 220 movies in his career. Loos had prominent roles in some of Fritz Lang’s and Germany’s most successful and artistically bold movies both in the silent and sound era, such as Die Nibelungen (1924), Metropolis (1927), M (1931) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933).

He remained in Germany during the Nazi regime, and received numerous accolades for his work during this period. He mostly appeared in entertainment films, such as historical dramas and crime movies, but did also star in a number of propaganda works, including director Veit Harlan’s infamous anti-semitic blockbuster Jud Süß (1940). He was wounded in the bombings of Berlin in 1943, and suffered from bad health during the rest of the war, which hampered his acting career, and in 1945 it came to a standstill in 1945 after the fall of Adolf Hitler. For his membership in the Nazi party and his involvement in propaganda films, he was blacklisted for two years, despite pleas from his colleagues and friends, even some that had been persecuted by the Nazis. Loos was considered an apolitical person who was simply trying to survive and excel in his profession – and to work as an actor in Nazi Germany a party membership was almost unavoidable. His reputation was quickly re-established and he continued his acting career in 1947. In 1954 he was awarded the Grand Cross of Merit of the German Republic and in 1956 a street was named after him in Berlin.

Luise, the woman in chapter 3, who sacrifices her fiancé and her parents for her love of Homunculus, is played by Norwegian actress Aud Egede-Nissen (ilo silmälle). A stage actress turned film star, she arrived in Germany via Denmark in 1914, and appeared in over 80 German films before she returned to Norway with the rise of Nazism in 1931. She worked with many of Germany’s most legendary directors, and appeared in films like Ernst Lubitsch’s Anna Boleyn (1920), Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922) and F.W. Murnau’s Phantom (1922).

Egede-Nissen is noteworthy for being one of the female pioneers of German cinema, as she founded her own film company Egede-Nissen Film Co. in 1917, for which she produced nearly 30 films, often with husband Georg Alexander as director, but sometimes taking on directorial duties herself. Most of these films are lost and forgotten, and production notes suggest them to have been fairly simple melodramas in serial form or detective films. Her company folded in 1920, partly due to the massive centralisation and nationalisation of the German film industry, now dominated by the behemoth UFA. Her later husband Paul Richter became one of Germany’s leading stars thanks to his turn as the male lead in Lang’s Die Nibelungen. Paul Richter remained in Germany and the couple were divorced as Aud moved to Norway in 1931, but she nonetheless kept her adopted name Aud Richter, and dropped her stage name of Egede-Nissen, for which she was known in Germany. Unimpressed with the Norwegian film industry, Richter now returned to the stage, and embarked on a remarkably successful career as a theatre director in the forties, and is especially remembered for her productions at the Norwegian National Theatre between 1955 and 1962.

In another small role we see Maria Carmi, an Italian-Swiss actress born Eleanora “Norina” Gilli in Italy. She rose to fame as a stage actress through Max Reinhardt’s acting school, and soon became an international stage success. Her most notable performance was as the Madonna in the original spectacle-pantomime play The Miracle written by Karl Vollmöller whom she married in 1904. The play was originally produced in Germany, but opened to rave reviews in London in 1911, and was revived on Broadway in 1924. In all she gave over 1 000 performances of the play. Maria Carmi appeared in some 30 films in Germany and Italy between 1912 and 1926, and was a minor star at Deutsche Bioscop during WWI. She is best known for her first movie, a British-Austrian adaptation of The Miracle (1922), one of a handful of early films made in colour and as lavish multimedia spectacles, complete with live music and sound effects, stage sets surrounding the screen, as well as live actors as extras and dancers.

Carmi remarried in 1917, with Georgian diplomat, Prince Georges V. Matchabelli, and in 1922 the couple moved to the United States, where they lived penniless until they started up their own perfume shop. Prince Matchabelli was an amateur chemist and along with his wife, now Princess Norina Matchabelli, he founded the perfume manufacturing company Prince Matchabelli in 1926. The brand, known for its crown-shaped bottles designed by Norina Matchabelli, quickly became hugely successful, and Norina sold it for a nice profit in 1936 after the death of her husband. The brand is still manufactured today.

In the early thirties Norina Matchabelli became a devotee of crackpot Indian mystic Meher Baba, one of the first crackpot Indian mystics to make a huge impact on rich, gullible American media stars. In the forties Matchabelli proved her own pot had cracked by giving a series of talks in prestigious venues throughout the US, where she claimed to channel the conscience of Meher Baba, and delivered “his” speeches through “thought-transmission”. She remained a follower until her death in 1957, and requested her ashes be interred near Baba’s burial site in India.

Homunculus also has small roles by actor-director Lupu Pick and Auschwitz victim Thea Sandten, who both appeared in The Tales of Hoffmann, please read more about them in that review if you are interested.

Some may protest the inclusion of Homunculus in a blog focusing on science fiction films, claiming it is fantasy rather than sci-fi. These protests are not wholly without merit, as Homunculus seems to possess magical powers, and much of the film proceeds without much sci-fi.

However, the homunculus is not in itself a magical or even mystical being, but rather one dreamed up by scientists in the 16th century, at the beginning of the scientific revolution. It was famed toxicologist, alchemist and “prophet” Paracelsus who first described the “scientific” method of creating a homunculus in 1537. Without going into detail, Paracelsus explains that homunculi are created by injecting a human sperm into a cucurbit, a squash of a cucumber are perhaps most proper for the purpose, as the cucurbit is then to be inserted into a horse’s womb, where it should be left to rot for 40 days. After this, one is to feed the still ethereal homunculus with human blood, inserted into the horse’s womb for another forty weeks, after which a fully formed homunculus is ready to be “born”. Other alchemists had other methods of creating homunculi, and due to mistranslations Paracelsus’ “horse womb” became “horse manure” at some point.

Paracelsus may have been inspired by the folklore regarding the mandrake root, which can at times resemble a humanoid figure, and has been the object of much superstition through the ages. But the homunculus theories in turn inspired writer Hanns Heinrich Ewers, who wrote the novel Alraune in 1911, which has been a popular source for German film adaptations through the years.

However, the film Homunculus misrepresents the classic homunculus, which is not a large monster-man in the vein of a golem or a Frankenstein monster. While homunculi are sometimes claimed to have supernatural powers such as foresight, alchemists universally described them as miniature versions of humans, often contained in glass jars. A version of homunculi closer to the original legends can be seen for example in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review).

The film Homunculus doesn’t explain in any detail how the homunculus is made, but makes very clear that it is created with the aid of science. We see Dr. Ortmann and his colleagues fire up a semi-translucent machine with lights inside, that for some reason makes me think of a mix between an art nouveau jukebox and a glass cabinet. One of the scientists takes a glass sphere containing whatever raw materials make the creature, inserts into the machine, and after a moment’s blinking a whirring a child is produced from the contraption.

As stated before, the film series was a huge sensation upon its release, and has drawn positive criticism from modern reviewers. Some complain about the broad acting, but confess to liking the film nonetheless. Nicolas Rapold at the New York Times writes that the film “exerts a special power with its serial suspense and haunting scenario”. Film scholar David Bordwell praises the pictorial ambitions of the filmmakers, and writes that some of the reasons why the series is so compelling are partly that it offers a “fairly original reworking of the Frankenstein premise” and partly that “its central conceit of a mad, misunderstood supervillain in search of love can evoke some empathy. There’s also the effort to convey a world in flames, to suggest a cosmic catastrophe with minimal means.”

It’s been speculated that Homunculus would have influenced Universal’s 1931 film Frankenstein, but if it did, then it probably did so indirectly rather than directly. Frankenstein was mainly influenced by the stage play that it was based upon, which contained all the significant discrepancies between the film and the book, such as the muteness of the creature and the emphasis on electricity rather than chemistry for its awakening. While James Whale’s film was most certainly inspired by German Expressionist movies, one should remember that Homunculus had a very limited distribution outside Germany, and was never screened in the States. None of the central people involved in Frankenstein were German. It is naturally within the range of possibility that British Whale or French Robert Florey could have caught a screening in Europe, but there are many more obvious inspirations, which were shown widely in the US, as well as Britain and France.

Homunculus is, however, the first feature film in which a human is created by the means of science, so credit where credit’s due.

Janne Wass

Homunculus, 1916, Germany. Directed by Otto Rippert. Written by Robert Reinert. Starring: Olaf Fønss, Friedrich Kühne. Ernst Ludwig, Albert Paul, Max Ruhbeck, Theodor Loos, Aud Egede-Nissen, Mechthild Thein, Maria Calmi, Lore Rückert, Lia Borré, Lupu Pick, Gustaf von Wangenheim, Ernst Benzinger, Margarete Ferida, Einar Bruun. Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann. Production design: Robert A. Dietrich. Produced by Hanns Lippmann for Deutsche Bioscop.

Leave a comment