A giant alien machine descends to Earth and proceeds to drain the planet of energy in this 1957 Fox B-movie. The script is creaky, but this is a fairly original and well designed low-budget effort from the mind of Irving Block. 6/10

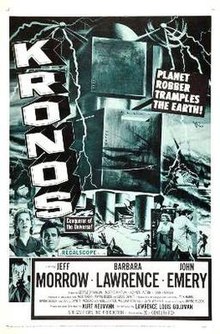

Kronos. 1957, USA. Directed by Kurt Neumann. Written by Lawrence L. Goldman & Irving Block. Starring: Jeff Morrow, Barbara Lawrence, George O’Hanlon, John Emery, Morris Ankrum. Produced by Irving Block, Jack Rabin, Louis DeWitt & Kurt Neumann. IMDb: 5.7/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 5.4/10

Dr. Gaskell (Jeff Morrow), his girlfriend/assistant Vera Hunter (Barbara Lawrence) and Dr. Arnie Culver (George O’Hanlon) are tracking a strange meteor heading for Earth in their high-tech observatory/computer central/nuclear lab. After trying to blast it out of the sky with atomic bombs, it crashes, undharmed into the ocean outside the coast of Mexico. Gaskell has observed the meteor changing its course unnaturally, and is convinced it is some alien intelligence, and there three scientists head down to Mexico to investigate. One day a mighty metal machine appears on the beach and heads towards the nearest power plant, utterly destroying it, while the Mexican air force trying to stop it are completely helpless against its impenetrable hull. If anything, it seems to feed off the energy released by the bombs, growing ever bigger.

This is the setup, or more or less half of the movie, of Kronos, the 1957 brain child of the dynamic duo of Jack Rabin and Irving Block. The two partners ran an independent all-purpose effects shop, mainly specialising in making good-looking effects for films that didn’t necessarily have the budget for good-looking effects. But they were also highly creative artists, designers, idea-men, writers and producers, and many of their most interesting projects were dreamed up by themselves, most famously MGM’s Forbidden Planet (1956, review). Such was also the case with Kronos, which was based on a story treatment by Block. Distributed by 20th Century-Fox, Kronos was a low-budget movie, but not super-low budget, and it is generally considered as one of more original SF movies of the 50’s.

Parallel to the action in Mexico, we follow the research station’s director, Dr. Eliot (John Emery), who is possessed by an alien intelligence, which manifests itself as a separate identity in Eliot, and seems to grow stronger after each time Eliot has been treated with shock therapy, due to which psychiatrist Dr. Stern’s (Morris Ankrum) belief that Eliot is suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. During his sessions with Eliot, Stern learns that Eliot believes that he is possessed by an alien entity from a race that has learned to convert pure energy into matter. This race has now depleted all its energy sources, and is roaming the universe in search of power with which to power up its batteries. After returning to the US, Dr. Gaskell catches Eliot during one of his lucid moments, and realises that the alien machine, which Gaskell has dubbed “Kronos” is actually one of these giant batteries, which grows bigger and stronger the more energy it consumes. Shocked, he learns that the alien entity in Eliot has advised the Pentagon to hit Kronos with a hydrogen bomb – and the bomber is already on its way. Now Gaskell, Hunter and Culver don’t only have to convince the military brass to call off the bombing, but also device a way to stop an impervious monster who seems to feed on the Earth’s strongest weapons.

Background & Analysis

Kronos was produced by Regal Films, which was a subsidy that producer Robert Lippert created for the purpose of making films for 20th Century-Fox to distribute – most of them were horrors or westerns. I haven’t found any precise information about how the project came about, but according to some sources, director Kurt Neumann was the person who brought the film to Regal Pictures. Probably, Block and Rabin, who had worked with Neumann before, pitched the movie to him, and him having a previous relationship with Lippert, brought the movie to him. Block’s story treatment was converted into a script by Lawrence L. Goldman, who had primarily written for TV anthology programs prior to Kronos. Apparently Fox president Spyros Skouras liked the concept of the movie, and encouraged its production. However, shortly before filming commenced, Fox cut the budget to a mere $160,000, which was not a lot for a movie of this caliber. This necessitated a rewrite of the script, cutting most of the character development and some of the more expensive special effects scenes.

The movie was shot in Los Angeles over two weeks in the beginning of 1957. Critic Glenn Erickson recognises several sets from other Fox films, as well as stock footage from Fox movies, leading him to surmise that it was filmed at the Fox lot. He also recognises shots of people fleeing Kronos that is stock footage shot in Hawaii.

The story merges several tropes from science fiction into a surprisingly well-functioning end product. The idea of the THING that keeps feeding and growing exponentially, threatening to consume the Earth, has echoes from H.G. Wells‘ 1904 book The Food of the Gods, but was most famously refined into its definite form by Arch Oboler in a 1937 episode of the hugely popular radio show Lights Out, titled “The Chicken Heart”. The story concerns an experiment with a chicken heart that starts growing out of control. The idea was reused by producer Ivan Tors in the movie The Magnetic Monster (1953, review), starring Richard Carlson, in which a new kind of radioactive material starts gobbling up energy, growing exponentially in the process. Was the story for Kronos not otherwise so different, one might almost accuse Irving Block of plagiarism.

The idea of an alien intelligence possessing or cloning humans has often been compared to either Invaders from Mars (1953, review) or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review). However, beside the alien angle, the way the possession plot plays out in Kronos more closely resembles that of Curt Siodmak’s best-selling novel Donovan’s Brain (1942), which has been adapted for film numerous times. Like the protagonist/antagonist of the novel, Dr. Eliot in the film develops a sort of dual personality, and tries to fight the influence of the invader in his lucid moments.

It’s also impossible not to see references to Gojira (1954, review), which had been released with much success in the US and internationally as Godzilla, King of the Monsters (review) in 1956. Like Godzilla, Kronos is a giant, radioactive monster roaming the countryside, laying waste to cities and threatening to topple civilisation. The scenes of people fleeing Kronos could be directly lifted from the Japanese movie, as could the scenes of a helpless military bouncing their bombs off the metal hull of the alien machine.

There’s also a nod to Irving Block’s previous project, Forbidden Planet, which he also provided the story treatment for. Like the Krell in that movie, Kronos also comes from a planet of brilliant scientists, whose triumphant technology has ultimately sowed the seeds of their own destruction. The impressive design of the majestic Krell cities is mirrored in the design for Kronos.

Several implications can be read into the title Kronos. Kronos, or Cronus, was the leader of the titans in Greek mythology, and became the ruler of the world after castrating and overthrowing his father, Uranus. Later, after a learning of a prophecy according to which one of his children would overthrow him, Kronos proceeded to eat all of his offspring, leading to one of the most famous images of Greek mythology. In his paranoid hunger for power, Kronos ultimately ensures his legacy will dwindle and die, leaving no-one behind to carry on the family line. Kronos’ hunger could be interpreted as an allegory for our society’s rampant consumerism, with the alien robot consuming the Earth’s resources, threatening to leave the planet an empty, barren shell. Of course, this was a potent theme in the 50’s, with the economy bouncing back from the war, fuelling a growing middle-class manifesting its newfound economical security through materialism.

The film could also be interpreted from the point of view of the American debate in the 50’s over nuclear energy and nuclear arms. Kronos the alien may represent nuclear fission as the new king of the Earth, the technology to end all technologies, threatening not only to symbolically castrate its creators and take on a life of its own, but also ultimately devour the children of the nuclear age. Similar warnings about the new radioactive future had certainly been made in numerous films prior to Kronos, but this film still succeeds in presenting the theme with a feeling of originality.

The inclusion of the possession subplot os ingenious inasmuch as it provides a natural way for the filmmakers to explain what is going, having Dr. Eliot act as a source of exposition that doesn’ feel contrived. Exactly what the relationship between Kronos and Eliot is remains vague, though. Eliot is affected with pain and seeming energy surges when Kronos is either consuming energy or being attacked. But it is unclear whether the entity controlling him is also controlling Kronos, or the other way round, or if they have any such connection at all. It’s also somewhat unclear why the alien entity chooses to possess Eliot. The only concrete reason for this seems to be so that he, as the nation’s top nuclear scientist(?) can advise the Pentagon to fire atom bombs at Kronos. But, then, wouldn’t it have been more logical to possess the head of the Pentagon?

Speaking of Eliot, the research station where he and the other protagonists work is also a mighty strange one. It seems be both an observatory and a nuclear research station, as well as having a complete hospital on site, and a ginormous computer. The computer, nicknamed SUSIE, of which Dr. Culver is the guardian, also breaks the principle of “Chekhov’s gun”. While the computer features heavily in the opening of the film, and much fuss is made about it, it never really ties in with the plot, other than the fact that when Culver is explaining some principle of the workings of the computer, it gives Gaskell an idea of how to defeat Kronos. But the computer itself serves no real story purpose.

Unfortunately, Block’s idea is better than Lawrence’s script. Not that the script is terrible. Plot holes don’t abound in the same way as in many similar movies, and it is a rather well-balanced script without cold war histrionics. There is a lot of techno babble, but the techno babble mostly serves a purpose. The dialogue, however, is rather trite, and it is particularly clear that romance wasn’t Lawrence’s forte. Every time Gaskell and Hunter make cute, you want to bury your head in a pillow. Kudos for making the woman part of the research team, but couldn’t they have made her a “Dr.” as the men, rather than an assistant, when they were at it?

However, the main problem with the script is that there is too little of it. This may have been a result of the last-minute budget slashes, but there just isn’t enough story to stretch over the film’s 78-minute running time. Editor Jodie Copeland pads out at least ten minutes of the movie with never-ending shots of the three protagonists flying around Kronos in a helicopter, and every shot of someone walking down a hall or opening a door just seems a little too long. There would have been ample time for some character development, but instead we get a wholly pointless attempt at some sort of romance, probably because the studio insisted there be one. “Will you marry me?”, Hunter blurts out of the blue in a completely unnecessary scene when she and Gaskell are making out on a beach, apparently taking some time off from their UFO search. The Kronos doesn’t show up until past the halfway mark of the movie, and most of the action is crammed into the last third, probably because the budget cuts didn’t allow for more special effects footage. This makes the middle of the film sag considerably.

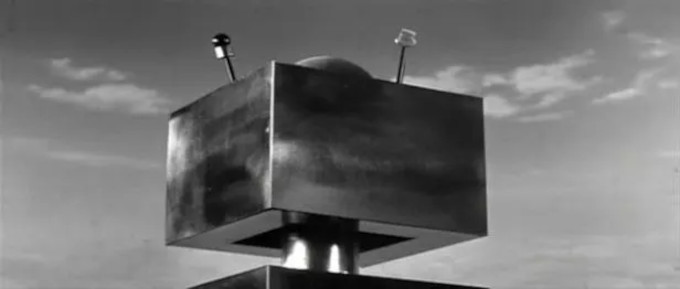

The special effects vary somewhat in quality, but on the whole they are good for what must have been a fairly low budget. The most unique thing about the film is of course the design of Kronos. It’s monolithic appearance looks like nothing seen in science fiction movies previously, and Stanley Kubrick no doubt took some inspiration here. There is a scene in which the three protagonists land on the “roof” of the machine, and the combination of sets, false perspective miniatures and what is probably rear-screen projection is quite good. The model does look somewhat miniaturesque in some shots, but overall Kronos is an impressive design, as long as it is stationary. But when it starts moving on its piston-like, CEL-animated legs (which btw function in a way that defy the laws of physics), the illusion is broken. I wonder if this wasn’t a concession to the slashed budget. There is also some subtle but very good stop-motion work by Wah Chang of Star Trek fame. Block and Rabin tended to excel in making impressive miniature models for low-budget movies, and Kronos is no exception. Especially memorable is the work in which Kronos lays waste to the Mexican power station.

Kurt Neumann was a capable director of B-movies, which he had shown in Rocketship X-M (1951, review), where Block and Rabin worked on the special effects, and his direction is on the whole effective and sometimes quite atmospheric in Kronos – even if he is hampered by the lack of enough script. He is helped, though, by the dramatically bombastic music of Paul Sawtell and Bert Shefter, enhanced also by the original sound design by James Mobley, especially impressive in the scenes with Kronos. Together they create a veritable wall of sound, heightening the menace of the alien machine. Behind the lense was Karl Struss, one of the true giants of Hollywood cinematography. In days past, Struss had been the cinematographer on such films as F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review), Cecil B. DeMille’s The SIgn of the Cross (1932) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940). Of course, Kronos didn’t quite offer the kind of material nor time and budget that these classics did. However, Struss brings to the picture a feeling of class and quality, and even otherwise nondescript shots are made enjoyable through his steady hand at the camera. The feeling that the film is more expensive than its measly $160,000 is enhanced by the wide, so-called “Regalscope” format.

The cast is made up of a better-than-usual B-movie cast, with some of the actors at home in bigger budget fare as well. Jeff Morrow is convincing in the lead — in an interview with Tom Weaver, Morrow says he read up on the technical details and had a grasp of what he was saying — or at least sounded like he did. Barbara Lawrence’s role doesn’t give her much to work with, and she does struggle with the awkward dialogue. George O’Hanlon as the sidekick gives a sprightly performance. John Emery as the possessed scientist is the stand-out performer, and it is nice to see SF stalwart Morris Ankrum in a sizeable role as the psychiatrist — and to see him outside of a military uniform. Unfortunately, the characters are no more than vehicles for the plot, and are written as cardboard cutouts. The film also features, in a small role as a pilot, Richard Harrison, who later became a star of Italian peplums and spaghetti westerns, as well as European and Asian exploitation films, as well as SF staple Robert Shayne, and Marjorie Stapp, who had a large supporting role in The Monster that Challenged the World later in 1957 (review).

Kronos is an SF movie of considerabe originality in a moment in time when much of the genre fair churned out felt like xerox copies of films that had come before. A strong story, good performances, interesting design, fairly well executed special effects and a powerful soundtrack lifts this above the average. However, the script itself is rather weak, and the last-minute budget slashes hurt the film, which should have been cut down to a B-movie running time of 60 minutes, rather than 78. It takes too long to get to the point, and severely treads water in the middle. It was released in many areas as a double bill with She Devil (review), also directed by Kurt Neumann.

Reception & Legacy

Kronos premiered in April, 1957, and, as stated, was often accompanied by Neumann’s own She Devil as a double bill. It grossed around $600,000 at the domestic box office, easily earning back its budget.

Kronos recevied middling to positive reviews upon release. The Los Angeles Times wrote that the special effects were “the best seen in a long time”, and called Kronos “quite well designed”, but lamented the dull characters. Syndicated Daily News called it a “not-too-good, not-too-bad science fiction job”, and gave it 2.5/4 stars. The trade press lauded Kronos’ exploitation potential for movie theatres. The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: “This is a bustling but improbable science fiction meller, made on a small budget, but with a brassy flair”. Harrison’s Reports called it “an acceptable science fiction program thriller”. The Motion Picture Daily was more impressed, writing: “Kurt Neumann […] proves beyond question […] that he is still the champion in this field of melodrama. […] Much realism is to be credited, too [beside the special effects], to the splendid photography by Karl Struss, and sound engineer James Mobley’s work figures vitally in adding to the film’s convincing impact”. And Variety said: “Kronos is a well-made, moderate budget science-fictioner which boasts quality special effects that would do credit to a much higher-budgeted film”.

Today Kronos has a 5.7/10 audience rating on IMDb based on 2000 votes and a 5.4/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes. AllMovie gives it 3/5 stars, with Bruce Eder calling it an “unusually handsome” B-movie “and displaying special effects that, if not always first-rate, were never less than fascinating in their design, detail, and execution”. Eder continues: “the acting […] is uneven and the script could have used another pass or two by a good editor; but despite these flaws […] Kronos never sinks too far into a juvenile level for it to be appreciated by adults”. TV Guide states: “Despite a low budget, this isn’t a bad film. The special effects, though not topnotch, are rather good.”

Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant is a big fan, calling Kronos “the most over-achieving low budget Science Fiction films of the 50s”. Erickson waxes almost poetical about the alien machine’s design: “Kronos is a subversive fantasy and Kronos itself a powerful symbol. The titan’s design is brilliant. Its simple collection of shapes has no style and no personality. It defies analysis. Surely Stanley Kubrick learned his 2001 lesson here; like Arthur Clarke’s Monolith, Kronos doesn’t date. In this movie, kids, Earth is invaded by Abstract Art from outer space. Every view of Kronos remains fascinating. It stands on the horizon, its head in the clouds, an unexplainable manifestation of an unknowable Future.” He does note that the story is pure pulp fiction; “The level of the dramatics in Kronos is strictly 50s-glib, closer to The Giant Claw than Forbidden Planet“.

Mark David Welsh, however, is not a fan: “Kronos himself isn’t very awe inspiring either – just two boxes connected by cylindrical legs and when he goes walkabout the effects are pretty silly”. He concludes: “Even at a scant 78 minutes this feels pretty stretched. Not one to linger long in the memory.” Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV writes: “Kronos is a minor addition to the 50s science fiction boom, but it has its moments. Get past the dull characters and their tendency to jump to conclusions that even the most brilliant of scientists wouldn’t be able to without the aid of a scriptwriter in a hurry to keep the plot moving and there’s still a lot to enjoy here.”

Kronos won’t make anyone’s top lists of science fiction films, and it sits at number 76 on Flickchart’s list of the 100 best SF movies of the 50’s – a spot that is perhaps undeservedly low.

Cast & Crew

Director Kurt Neumann was born in Germany in 1908. He worked briefly in the German film industry in the late twenties, and had only directed one short movie before he was brought to Hollywood to direct German-language versions of Hollywood movies. This was during the short-lived era at the beginning of sound films that studios would make the same movie in different languages, often with different actors and directors. However, Neumann quickly mastered English and established himself as a director in his own right, and made a couple of well-regarded films for Universal in the early 30’s. These included The Big Cage (1932), a circus movie which included several scenes with lions and tigers being handled by lion tamer Clyde Beatty, that were famously re-used in the SF/horror film Captive Wild Woman (1943, review). He freelanced for almost all major studios, before being picked up by RKO to direct a string of Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films in the early 30’s. Neumann worked primarily on B-movies for major studios, but also freelanced for smaller outfits like Monogram and Allied Artists.

In 1950 crafty freelance producer Robert Lippert took advantage of the media hubbub around George Pal’s upcoming Destination Moon (1950, review), and hurried out the low-budget movie Rocketship X-M (review) a few weeks prior to Pal’s humdrum moon adventure. As director, he hired Neumann, and as cinematographer Karl Struss, and the duo was able to make a surprisingly competent space movie on a short schedule and little money. Neumann has since been labelled as a “science fiction specialist”, but in truth he didn’t make that many SF movies – which is a shame, as he clearly had a knack for the genre. Along with Struss as his cameraman, he directed Kronos, She Devil and perhaps most famously, The Fly (1958, review).

According to a persistent legend, Neumann committed suicide after the first screening of The Fly in 1958. This, however, is not true, in fact he died of natural causes in his home. This legend, however, has led the infamously “inventive” movie historian Gary Westfahl to build up an entire biography on Neumann based on the notion of the “depressed artist” – reading numerous made-up biographical notions based on Neumann’s supposed suicidal tendencies into his movies (you can read this atrocity here). However, Westfahl does also raise an interesting “what if?”; “Neumann might have had a better career if, from the start, he had been allowed to specialize in horror films; […] All in all, he probably would have done a little bit better than Curt Siodmak if he had inherited the task of keeping the Universal horror franchises alive during the 1940s. Instead, he was given the chore of overseeing another durable property—Tarzan—during its period of steady decline, and he did so about as well as could be expected.”

Karl Struss was favourite of Neumann’s and they worked together on many films in the 40’s and 50’s. But in his earlier career, the New Yorker was, as mentioned above, one of the hottest cinematographers in Hollywood, with credits F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review), Cecil B. DeMille’s The SIgn of the Cross (1932) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940). He also shot one of the best sci-fi films of the thirties, Island of Lost Souls (1932, review). He also, bizarrely, filmed the turkey Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review) and The Alligator People (1959).

Irving Block and Jack Rabin are unsung heroes of low-budget SF, often working with Louis DeWitt on special effects, writing and producing. Rabin and Block had started their sci-fi collaboration on Rocketship X-M, with Neumann and Struss, and continued on Flight to Mars (1951, review), and would go on to become B movie legends in the fifties. They went on to collaborate on Unknown World (1953, review), Invaders from Mars, World Without End (1954, review), Monster from Green Hell (review), The Invisible Boy, Kronos (both 1957), War of the Satellites (1958, review), The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959) and Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review). Both also worked on a number of other sci-fi films separately. Rabin worked on movies including The Man from Planet X, Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), Robot Monster (1953, review), Deathsport (1978) and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Block did work on films like Captive Women (1952, review), Forbidden Planet (1956, review) and The Atomic Submarine (1959).

Wah Chang, who did stop-motion animation on the Kronos model, deserves an in-depth presentation, but we’ll get to that at a later point. Briefly, though, Chang was a sculptor and artists who entered Hollywood through the theatre, and did early work as a creator of maquettes at Disney for animation reference, and soon became amn all-round master of design, animation and special effects for films big and small, often through his company, which meant that his work often went uncredited. He is best known for his work in Star Trek, for which he designed not only the tricorder and the communicator, but also the Tribbles and Gorn, among much else. Chang’s work earned several Oscars, but because he worked through a company, he was never personally awarded.

Lead actor Jeff Morrow was a veteran of the stage, a Shakespearean actor with experience from radio. He made his screen debut in 1953 with a lead in the spectacular A-picture The Robe, one of the first to be filmed in Cinemascope, and got rave reviews for his performance. However, for one reason or the other, he wasn’t able to follow up on the hype, and spent most of the fifties alternating between A and B movies as a very respected character actor, but never a commercial star. He was picked up by Universal in 1955, as the studio wanted him for This Island Earth (review). Here, Morrow was immortalised as the dome-headed alien leader Exeter. He appeared in The Creature Walks Among Us in 1956 (review), and Kronos in 1957. Later the same year, he had another SF lead, in the infamous turkey The Giant Claw. And much later, in 1971, Morrow did a walk-on part in Harry Essex’ abysmal Creature from the Black Lagoon remake Octaman, filling in for an actor who got sick.

Barbara Lawrence had a short but moderately successfull Hollywood career stretching from 1945 to 1957. She often appeared in large supporting roles both in A and B movies, and made many appearances on TV. Kronos was her only SF role. George O’Hanlon had a long career as a character actor, often in good-natured or comedic roles. He is best known George Jetson. John Emery was a noted stage actor, who commanded romantic leads on Broadway in the 20’s. On film, he is perhaps best known for his supporting roles in the Ingrid Bergman films Spellbound (1945) and Joan of Arc (1948) and as Japanese premier Tanaka in Blood on the Sun (1945). Emery also played the expedition leader, a wooden role if there ever was one, in Rocketship X-M. Then of course, there is Morris Ankrum, a constant presence in science fiction films from the 50’s as military men, scientist and other authority figures. Ankrum was especially memorable as the Martian leader Ikron in Flight to Mars, as the colonel fighting aliens in Invaders from Mars and as the UFO-abducted general in Earth vs. the Flying Saucers. All in all, he appeared in at least 15 SF movies.

Look out for young Richard Harrison in the role of a US air force pilot! This was Harrison’s first movie role in a career that threatened to go down the same way is with many young beefcakes in the industry – doomed to play the topless cameo in a beach scene. He had a featured role in AIP’s Jules Verne adaptation Master of the World (1961), but his career really took off after he relocated to Italy in 1960. His lead in the sword and sandal movie The Invincible Gladiator (1961) led to a three-picture deal with distributor American International Pictures, which cemented him as a peplum hero, and later a star of the spaghetti western. Among his best known films are Gunfight at Red Sands (1963) and Antonio Margheriti’s Vengeance (1968). The former is famous for being the first spaghetti western to feature music by Ennio Morricone. Harrison was offered the lead in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), but turned it down, and instead recommended Clint Eastwood. He later joked that turning down the role was his greatest contribution to cinema.

When the spaghetti western waned in popularity in the 70’s, Harrison branched out into other genres, primarily modern action movies, eurospy films and thrillers, primarily in Italy, but also in countries like Egypt, Turkey and Yugoslavia. In the mid-70’s he started appearing in the increasingly popular Hong Kong kung-fu movies, a genre that would follow him for the rest of his career. By the 80’s, he was primarily making Z-grade films in Hong Kong and the Philippines. While ridiculed at the time, these ultra-low budget movies have since granted Harrison a cult following. Best known of these are probably Godfrey Ho’s infamous Ninja series, which included 24(!) films between 1984 and 1988. In fact, only a handful of movies were filmed, but Ho later reused the same footage and spliced it together to make more films. During this period Harrison also appeared in the American Z-movie Evil Spawn alongside Playboy bunny and scream queen Bobbie Breese and John Carradine. He relocated to the States in 1990, and appeared, primarily in supporting roles, in a string of further Z-grade movies before retiring in 2000. As of September 2023, Harrison is still alive and kicking. Considering Harrison’s long career in Z-movies, he did surprisingly few SF films, but still managed to get half a dozen under his belt. Apart from Kronos (1957) and Master of the World (1961), he starred in the superhero film Fantabulous, Inc. (1968) by Sergio Spina, the short-lived Italian post-apocalyptic TV series Ora zero e dintorni (1980), Evil Spawn (1987) and Steve Barkett’s genre mashup Empire of the Dark (1990).

Robert Shayne had a long and prolific career on stage, in film and TV, without ever becoming neither Broadway nor Hollywood nobility. He had a string of supporting roles in A films in the forties, notably opposite Bette Davis in Mr. Skeffington (1944) and Barbara Stanwyck in Christmas in Connecticut (1945), and is sometimes remembered for his brief turn opposite Cary Grant in North by Northwest (1959). More often, however, he was cast in small, prominent or even leading roles in B movies, such as The Spirit of West Point (1947), sometimes described as the worst sports movie ever made.

Shayne is best known for appearing as Inspector Henderson in the TV-series Adventures of Superman (1952-1958). He appeared in numerous sci-fi films, such as Invaders from Mars (1953, review), The Neanderthal Man (1953, review), in which he actually played the lead, Tobor the Great (1954, review), Indestructible Man (1956, review), the infamous The Giant Claw (1957), Kronos (1957), How to Make a Monster (1958, review), The Lost Missile (1958, review), Teenage Cave Man (1958, review) and Son of Flubber (1963). In the sixties and seventies he was mainly seen on stage and on TV, and he practically retired in 1977 after nearly 50 years in the film business. He made a brief comeback in 1990-1991, then 90 years old, in two episodes of the TV series The Flash, as a newsstand salesman. He was actually blind at the time, and learned his lines by having his wife read them out for him.

Janne Wass

Kronos. 1957, USA. Directed by Kurt Neumann. Written by Lawrence L. Goldman & Irving Block. Starring: Jeff Morrow, Barbara Lawrence, George O’Hanlon, John Emery, Morris Ankrum, Kenneth Alton, Jonn Parrish, Jose Gonzales-Gonzales, Richard Harrison, Marjorie Stapp, Robert Shayne, Don Eitner, Gordon Mills, John Halloran. Music: Paul Sawtell & Bert Shefter. Cinematography: Karl Struss. Editing: Jodie Copelan. Production design: Theobold Holsopple. Makeup: Louis Hippe. Sound: James Mobley. Visual effects: Irving Block, Jack Rabin, Louis DeWitt, William Reinhold, Menrad von Mullendorfer, Gene Warren, Wah Chang. Produced by Irving Block, Jack Rabin, Louis DeWitt & Kurt Neumann for Regal Films & 20th Century-Fox.

Leave a comment