Did you know that the first movie featuring a time machine is Hungarian? Or that in 1918, Denmark released the first feature film about a trip to Mars? Or that prior to the German 1929 film Woman in the Moon, rocket launches usually featured count-ups, rather than countdowns? Much of the heritage in SF movies comes from non-English language films from the first half of the 20th century, many of which are largely unknown to an English-speaking audience today. Here we list the 25 greatest non-English language science fiction movies made prior to 1950. How many have you seen?

25. The Invisible Thief (1909)

We start the list with a French short subject from 1909. Le veleour invisible or The Invisible Thief was created by two of Europe’s cinematic power players, Catalan Segundo de Chomon and Parisian Ferdinand Zecca. It was one of the the first films to be directly based on H.G. Wells’ 1897 novel The Invisible Man – because of its 10-minute running time, it could perhaps be called an homage to the book rather than an adaptation. Picking up a copy of “G.H. Wells”” novel “L’Homme Invisible”, a man is inspired to create his own invisibility serum in a hotel room. He drinks it and turns invisible, then undresses and proceeds downstairs to steal the hotel’s silverware. He hides the loot in his room where he again dresses and puts on a mask to pass as visible, after which he proceeds to the street, where he mugs a rich couple. Spotted by the police, he is chased back to his hotel room, where a fisticuff with the invisible menace ensues. What makes this silly entry a contender is its marvellous special effects. In 1932, Universal’s classic adaptation starring Claude Rains provided jaw-dropping invisibility effects that still awe modern viewers. The Invisible Thief uses much of the same techniques that Universal did, but 15 years earlier. This was the work of Segundo de Chomon, an unsung wizard of early cinema. Full review.

Available for free on Youtube, and as part of an official Chomon collection on DVD.

24. A Trip to Jupiter (1909)

Speaking of Segundo de Chomon, on spot #24 we include one of his solo efforts, and possibly his best SF-themed movie, A Trip to Jupiter. Like much of the SF output in the first decade of the 20th century, Le voyage sur Jupiter or A Trip to Jupiter builds on the stage-inspired tradition of fantastical voyages pioneered by the legendary Georges Méliès. However, Chomon quickly surpassed the French master with his innovative use of the camera, freeing it from the static, horizontal plane favoured by most filmmakers at the time. One of his specialities was mounting the camera in the ceiling, shooting down towards a black floor, an effect he makes brilliant use of in this whimsical short from 1909. Following a king’s journey to Jupiter, leading to a frenzied, electrical battle with the god of thunder, the film contains what must have been the longest continuous tracking shot from the ceiling in this point in film history, as the protagonist “climbs a ladder” from the Earth to the red planet. In fact, the ladder is laid out on the floor. Another superb shot is when the king is thrown off the planet and plummets to the Earth, in a wonderfully psychedelic sequence, again employing the bird’s eye perspective and some beautiful use of scenography. Chomon relies less on the gimmicky stop-shot and replacement shot techniques for effect – they were becoming slightly old hat even by 1909 – and more on his whimsical imagination, camera placement and innovative use of sets. Even while Georges Méliès was “rediscovered” not once but three times by movie buffs between the thirties and the naughties, Chomon’s legacy sadly fell into neglect with the coming of the narrative feature-length film and the new standard of realism in the 1910’s, and it is only recently that this artist has been rediscovered. Full review.

Available for free on Youtube, and as part of an official Chomon collection on DVD.

23. Sziriusz (1942)

Now on to our first feature film, and our first talkie on the list. This Hungarian 1942 production is the first movie to feature a time machine. Directed by Desző Ákos Hamza, the movie is based on a play, which is in turn based on a 1894 short story by Ferenc Herczeg. Sziriusz is a lavish costume drama-cum-political satire, framed as a time travel story. Arrogant aristocrat playboy Count Tibor (László Szilassy) agrees to test fly a dotty scientist’s time machine. But there’s an accident — Count Tibor falls out of the machine in the middle of the 19th century, where he gets embroiled in the political and romantic machinations of the Habsburg nobility, and falls in love with the beautiful Venetian singer Rosina (Katalin Karády). However, he has a rival for Rosina’s hand — his own great-great-grandfather, a wealthy, arrogant playboy whom Tibor immediately takes a disliking to.

This film uses the SF element as a ploy to transport its protagonist to the era the story is set in — much like Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee getting whacked in the head with a crowbar. The rest is all-out costume drama, and a wonderfully staged one it is. With its lavish budget, costumes and choreography it doesn’t pale a bit compared with its Hollywood counterparts. But there’s also a sly, running social commentary aimed at the Nazi influence over Hungary in 1942 — officially Hungary was allied with Nazi Germany at the time. A hundred years earlier, the Hungarians were at the mercy of another “occupying” force, the Austrian Habsburg dynasty. And while poking fun at the Habsburgian royalty, the film wouldn’t have had to twist the audience’s arm at the time in order to get them to draw parallels to the pro-Nazi government of the era. It would be a stretch to call Sziriusz a political film, however, as it is a breezy “man out of time” comedy romp, heightened by the charismatic presence of the immensely popular singer and movie star Katalin Karády. Full review.

Available for free on Youtube without subtitles, and with English subtitles as bootleg DVD.

22. The City Struck by Lightning (1924)

The first film featuring a “death ray” is a French silent production from 1924. La cité foudroyée, or The City Struck by Lightning was written by the critically acclaimed mystery and horror writer Jean-Louise Bouquet, and is almost completely forgotten today. The movie followed on the heals of infamous British inventor Harry Grindell Matthews’ visit to Paris, to shop around his purported “death ray” which his own government had refused to pay for (because he couldn’t prove it worked). This dark and brooding silent film follows a young inventor obsessed with perfecting a death ray which can pull down lightning from the sky, in order to win the hand of his beloved. The somewhat contrived story relies on the plot twist that the girl’s uncle is dying and has promised to give her away to the person who can present the largest dowry. After locking himself in his study for ages, growing ever darker and moodier, the romantic protagonist one day meets a mysterious, up-to-no-good businessman who promises to help him build the huge power plant that the death ray would require. In secrecy they set to work, as the deadline for the bid for the girl’s hand draws near. With only one day left, the Parisian authorities receive a mysterious letter by a man who threatens to burn the city to the ground unless they pay him a fortune … The contrived and melodramatic script is balanced by Luitz-Morat’s atmospheric and dark visuals, good acting and one of the better final plot twists in movie history. Full review.

Available for free on Youtube.

21. The Tales of Hoffmann (1916)

At #21 we present not only our first German SF movie but the first German SF movie, Hoffmanns Erzählungen, or The Tales of Hoffmann, from 1916. A romantic tragedy, this one is based on Jacques Offenbach’s opera with the same name, which is in turn based on three stories by the pioneering Gothic author E.T.A. Hoffmann. A writer of the same era as Mary Shelley and Lord Byron, Hoffmann foreshadowed the existential and psychological horror of Edgar Allan Poe, often writing stories of unattainable love, death and tragedy with some metaphysical or supernatural twist. What puts him square in the field of SF is his story The Sandman, which is one of the very first to include a robot — or at least an automaton. Offenbach wrote the opera from a libretto by Jules Barbier in 1881, and it includes adaptations of the stories The Sandman, The Cremona Violin and The Lost Reflection, all stories dealing with death and lost love. The adaptation takes some of the punch out of the original stories, and in adapting an opera for a silent film, something else naturally gets lost along the way. But the core tales are good enough to keep the film afloat, and they are enhanced by some splendid acting and the moody, Expressionist atmosphere built by director Richard Oswald. Full review.

Available for free on Youtube and with English subtitles as bootleg DVD.

20. The Macabre Trunk (1936)

On to our Top 20 “foreign language” SF films, as the Americans would say. Of course, our #20 isn’t made in a language foreign to the US at all, as it comes from Mexico. El Baul Macabro or The Macabre Trunk, from 1936, is part of a string of so-called “medical horrors” produced in Mexico in the thirties, and it is arguably the best of the lot. Ramón Pereda is a mad scientist trying to save his mortally ill wife through blood transfusions — that is, he needs to drain young women of all their blood. Disguised in a black slouch hat, mask and cape, he steals patients from the local hospital and stacks their bodies in the macabre trunk of the title. His mistake is kidnapping the hospital director’s daughter Esther Fernandez, who so happens to be engaged to a young doctor played by genre cinema favourite René Cardona, who turns out to be quite the amateur sleuth. Highly inspired by the mad scientist films and serials of thirties Hollywood, the movie comes complete with a Dwight Frye-esque assistant, winding staircases and creepy basement laboratories, even a comic relief flatfoot. Stylishly shot by director Miguel Zacarías and Canadian cinematographer Alex Phillips. René Cardona is best known as the director of a whole slew of lucha libre films in the fifties, sixties and seventies. Full review.

Available for free on Youtube and as bootleg DVD, unfortunately only as a severely degraded VHS rip.

19. Skeleton on Horseback (1937)

Based on Karel Capek’s play, this 1937 Czechoslovakian dystopia, originally called Bílá nemoc, is a thinly veiled allegory on Hitler and Nazi Germany. The action takes place in an unnamed, big European country, which is ruled by a despotic leader by the title of Marshal (Zdenek Stepánek), who drums up support for an invasion of a neighbouring smaller country. The Marshal, giving charismatic speeches from the balcony of his Classicist, white mansion, dressed in a military uniform, is pastiche on Hitler and the country likewise a metaphor for Germany, at the time threatening to invade Czechoslovakia. But the country is ravaged by a mysterious, fatal disease, dubbed “the white plague”, because of its early symptoms, which are hardened, white and numb spots on the skin. As long as it only affects the lower classes, nobody takes great notice of it in government, their attention focused on the glory of the coming war. But a pacifist doctor (actor/director Hugo Haas) has found a cure. When the rich, including the Marshal himself, start getting infected, the country is thrown into panic. But the doctor refuses to divulge his formula — or cure the rich — unless parliament signs a peace treaty.

A life-long antifascist and one of history’s greatest satirical writers, Czech Karel Capek was never one for easy solutions and happy endings. But even by his standards, this is a bleak movie. Originally written as a play, it premiered at the Prague National Theatre in 1937, and was swiftly turned into a motion picture using the same director and actors. Star and director Hugo Haas later relocated to Hollywood, where he became best known for directing a number of erotically tinged potboilers. A bit long-winded and slow-paced for its own good, Skeleton on Horseback is nevertheless quite stylishly directed, taking advantage of great location shooting and the impressive architecture of Prague, and well acted. But more than anything, it is carried by Capek’s text. Full review.

I have not found any streaming options for the movie, but a restored version has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by the Czech National Film Archive, as a box set together with Krakatit.

18. Algol (1920)

With all the great silent films pouring out of Germany in the silent era, it is only natural that some of them are somewhat neglected and forgotten. Such a film is Algol from 1920, a sprawling futuristic epic that planted the seeds of later movies like Aelita and Metropolis. The film’s subtitle was “A Tragedy of Power”, which pretty much sums up the somewhat splintered plot of Algol. The movie follows the family Herne, whose patriarch Robert (the great Emil Jannings), a mine worker, is visited by an alien from the star Algol (John Gottowt of Nosferatu fame). The alien, “Algol”, provides Herne with the secret of how to build a machine that will provide endless free energy through “Algol rays”. With this secret, Robert builds up an empire, and as the sole keeper of the secret of eternal energy, his lust for power grows, until he becomes the de facto ruler of the world. But his hunger darkens his mind, and he is abandoned by his family and friends. Embittered and paranoid, he exploits the workers of the world, while his ex-girlfriend joins the socialist resistance and raises a son that stands up to challenge the Master of the World.

With impressive, Expressionist designs and a formidable cast, Algol put its finger on the political pulse of the era. However, director Hans Werckmeister, who’s primary experience was from the stage, isn’t quite big enough for his britches, and the script fumbles with the political content, settling for a somewhat meandering melodrama, which explains why Algol isn’t higher on this list. Worth seeing for the wonderful performances alone, including a magnetic cameo by scandal-prone dancer Sebastian Droste. Full review.

Available with English subtitles for free on Youtube, and as a beautiful 2020 DVD release by Editions Filmmuseum.

17. F.P.1. Does Not Answer (1932)

For #17 we’ll stay in Germany. F.P.1. Doesn’t Answer, or F.P.1. antwortet nicht, is a talkie (and, unfortunately, singie) from 1932, following the building of a floating gas station for airplanes in the Atlantic. In the early thirties, airplanes still didn’t have the range to fly non-stop over the Atlantic, and serious thought was being put into the possibility of building refuelling platforms in the sea. This was the theme of Curt Siodmak’s 1931 script and tie-in-novel, which follow the exploits of an idealistic engineer (Paul Hartmann), a daredevil pilot (Hans Albers), a shipyard co-owner (Sybille Schmitz) and a journalist (Peter Lorre), and their melodramatic machinations and tribulations in getting the impossible project done, amid nay-sayers and saboteurs. The script reads like a mix between a melodrama and a spy yarn, and threatens to sprawl out in too many directions. However, its flaws are patched up by Karl Hartl’s steady direction and the good cast, led by superstar and matinee idol Albers, well backed by later Hollywood villain Lorre. There’s also some very good model photography and an appropriately bombastic score – plus a couple of ill-advised song numbers, that were ubiquitous to the era. This was during the short era during early sound cinema before dubbing and subtitling had become staple, and films were still being made in multiple languages. An English and French version were also filmed simultaneously – with Conrad Veidt and Charles Boyer in the heroic roles. Curt Siodmak, of course, would go on to Hollywood fame as screenwriter, author and less so as director. Full review.

The English language version of the film is available for free on Youtube, and both the German and English versions have just recently been released on a beautifully restored Kino Lorber Blu-ray. The German version is also available on Amazon Prime.

16. The Crazy Ray (1924)

The second French feature film on our list comes in at #16. This silent treatment from 1924 was French avantgardist Rene Clair’s first feature film. Like The City Struck by Lightning, it was probably inspired by the hubbub around “death ray” inventor Harry Grindell Matthews. Here, a small group of people wake up in or arrive to Paris, only to find that the city, along with all its inhabitants, have frozen stiff in in mid-step, as if someone had hit a pause button on time. They soon realise that what they all have in common is that they have spent the night at high altitude. Kings of the city, they spend a few days enjoying themselves, but their existence soon settle into a mellower pace, as they make a home for themselves in the Eiffel tower, contemplating their lives as the sole survivors of some freak incident, examining their newfound relationships, forming bonds of friendship, love and antagonism. But the male squabbles over the last living woman in Paris are interrupted by a radio message from the daughter of a scientist, who announces that her father has created a time-stopping ray. Now the hunt is on.

The dormant Paris is beautifully filmed in Rene Clair’s feature debut, in a style later used ad infinitum by post-apocalypse and zombie film makers. The film is a ode to the cinema’s juxtaposition of action and stasis, a salutation to that dreamland of movies where fantasy and reality meet. Originally an hour in length, Clair himself cut it down to 35 minutes upon is re-release, and only as such was it available for decades. It has been restored later, close to its original running-time. Full review.

The full 50-minute movie is available as a low-quality stream on the Internet Archive and as a Pathé DVD/Blu-ray combo. The 35-minute re-release version can be streamed on the Criterion Channel.

15. The Extraordinary Adventures of Saturnino Farandola (1913)

Le avventure straordinarissime di Saturnino Farandola, directed by Spanish Italian actor-director Marcel Perez in 1913, is a milestone between two cinematic eras, that of the fairy-tale like and stage-inspired short films of Georges Méliès and the long narrative films of the new, realistic era. The film is based on a comical adventure novel by French author and illustrator Albert Robida from 1879, and concerns, well, what is stated in the title. Newborn Saturnino Farandola (Perez) is lost at sea, and like a Tarzan figure before Tarzan, raised by apes on a desert island. He is picked up by a merchant vessel, and is taken under the wings of the captain, who teaches him the ways of the sea and of civilisation. Farandola eventually becomes captain himself, fighting pirates, whales and marine biologists. The first kills his captain, the second eats his wife (whole and unharmed in a diving suit), played by Nilde Baracchi, and the third captures the whale and puts it in his aquarium, and figures that anything that the whale might regurgitate (say, the wife of a sea captain) is part of the bargain. Farandola and his wife have further adventures in Asia, before they arrive at the American civil war. Here Farandola must fight a most fearsome adversary: the ruthless Phileas Fogg of Jules Verne fame. To beat the opposing army Farandola devises of a number of creative weapons like chloroform bombs and a “pneumatic aspirator”, a giant vacuum cleaner built into the wall of his fort, which literally sucks up the enemy soldiers. The films is particularly remembered for its final part, which involves a fantastic war in the air, using hot-air balloons outfitted with cannons. Full review.

Available for free without subtitles on Youtube and with English subtitles as bootleg DVD.

14. Krakatit (1948)

It’s the second Czech film on our list, and the second film based on the works of Karel Capek! In Skeleton on Horseback the plot revolved around the invention of a medicine to save mankind. In this 1948 film we follow another scientist, but this one has created a new explosive, which threatens to annihilate mankind. Based on a novel from 1922, the film’s protagonist Prokop has invented a substance, “Krakatit”, that breaks apart the atoms of everything it comes in contact with, and can be activated through magnetic rays. In Capek’s treatment, it’s not only matter that breaks apart. Written shorty after WWI, it described the thoughts, feelings and the social constructs of the world, reality itself, being pulled apart at the atomic level. That director Otakar Vávra chose to pick up Capek’s book after WWII was hardly a coincidence. It’s a feverish, surreal nightmare, as Prokop, apparently hospitalised, drifts in and out of consciousness, unsure of what are recollections of real actions seen in flashbacks, and what is a fever dream. After creating his explosive, he is haunted by nightmares of what his creation will unleash upon the world. At one point his formula is stolen by a colleague. He is sought out by a secret pacifist society, through a beautiful, mysterious woman whose face melts away. In the end he is led by a demon to a control room and placed with the fate of the world in his hands — at the press of a button all the world’s major cities will go up in flame at the push of a button, and the world will be born anew.

Based on Capek’s perhaps most confusing and confounding work, the film cuts a few corners, simplifies and makes it accessible, without losing the original work’s darkness and hallucinatory style. It is morally less ambiguous, as it latches on to Kapek’s “Krakatit” and makes it into an allegory for the nuclear bomb, while Capek wrote more about ideas and the social fabric. Vávra’s film is perhaps somewhat sluggish in parts and perhaps a bit on the nose in others. But despite this it is still a powerful movie with subtext to spare and interesting twists a-plenty, especially of you haven’t read the book. Full review.

I have not found any streaming options for the movie (it is on and off on Youtube), but a restored version has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by the Czech National Film Archive, as a box set together with Skeleton on Horseback.

13. Gold (1934)

Back to Germany it is, with a second entry from director Karl Hartl, again working with the country’s biggest male movie star of the thirties and forties, Hans Albers. This time Albers is not an aviation ace, but a scientist, a modern day alchemist using what appears to be radioactivity in an effort to create gold out of lead. When his boss and mentor is killed in an apparent sabotage and two goons show up with an offer from a shady Scottish millionaire to continue funding his work, he smells a rat. However, he agrees to be flown out to a huge laboratory inside a mountain below the sea, in order to find out the true fate of his boss. Leaving his wife behind, he befriends the Scottish crime lord’s beautiful daughter, played by Brigitte Helm of Metropolis fame. A game of cat and mouse ensues, as enlists the help of an old acquaintance who also works for the villain to try and find out the fate of his mentor and the true motives of his “beneficiary”. One day, Albers succeeds in creating gold. But the initial triumph quickly turns sour, as the villain’s gold factory sends the global economy into panic, and the workers start worrying for their loved ones at home, who suddenly lose their jobs and are unable to support their families. Now Albers springs into action and the finale is an action-packed sequence equal parts disaster movie and James Bond.

The initial melodrama treads water for a while in this movie, and the slightly tacked-on relationship between Albers and Helm goes nowhere, but the second part, which takes place mainly in the impressive underwater factory/lab is both smart and visually impressive. So impressive, in fact, that Hollywood producer Ivan Tors lifted most of it for the 20-minute finale of his 1953 film The Magnetic Monster. Released in 1934, Gold was one of the last SF movies made in Germany before the genre was deemed unfit by the Nazis. There are a few — in retrospect — uncomfortable Nazi themes raising their heads in the film. One is that of the blood bond. Much is made of the fact that Alber’s wife saved him after the lab explosion with a transfusion, and that blood bond is the reason Albers politely brushes off the invitations by Helm — but the blood bond also takes on a symbolic meaning, as Albers refuses to betray the bond to his home country in order to get rich by helping a foreign crook. However, it would be historically inaccurate to label the movie as “Nazi propaganda”. Full review.

I have not found a streaming option for Gold (it is on and off on Youtube), but Kino Lorber has released a restored version on DVD and Blu-ray.

12. The Inhuman Woman (1924)

At #12 we find another French directorial legend, Marcel L’Herbier. The Inhuman Woman or L’Inhumaine was an expensive and ambitious flop, and is often considered to have been the final nail in the coffin for the short-lived Impressionist movement in French cinema. But this 1924 avantgarde is a vital and fascinating experiment in movie as art. The plot follows Einar Norsen (Jaque Catelain), a passionate and sensitive inventor who is one of many suitors to the rich but cold-hearted opera star Claire Lescot (Georgette Leblanc). Much of the film takes place during one of Lescot’s avantgarde soirees in her peculiar mansion, where she toys and discards fawning men, including Norsen. Norsen, however, sets out to teach this inhuman woman a lesson, and storms off after being insulted, crashing his sports car off a mountainside. Faking his own death, he makes Leblanc believe she made him take his own life. After wallowing in regret, Leblanc is led to a mysterious place, where a “spirit” offers her a second chance: it will resurrect Norsen if she admits the error of her ways. Arise, Norsen, and the two become lovers. The second part of the film then consists of Norsen showcasing his futuristic invetions (like satellite TV) and a jealous suitor out for murder.

Drawing on Soviet symbolism and montage theory, Impressionist art, Cubism and Constructivism, L’Herbier creates a whirlwind of a movie. His idea was that film was the ultimate medium for combining all aspects of art. He commissioned a modernist score to be played live at the premiere, to which he invited the creme de la creme of European nobility and art community. Some of them he hired as live actors, to shout insults at Georgette Leblanc during the movie — connecting her with the evil woman on screen. Neither audiences nor critics got it, and the film severely hurt L’Herbier’s career. But its visual style and themes struck a chord with many young filmmakers, and its influence can clearly be seen in films by Fritz Lang, James Whale and others. Full review.

Restored film available on Amazon Prime, Mubi, Vimeo on Demand and on DVD and Blu-ray by Lobster.

11. The End of the World (1916)

Narrowly edged out of the Top 10, this 1916 silent epic is Denmark’s first SF picture and the world’s first apocalypse movie. Verdens undergang or The End of the World is more inspired by than based on SF pioneer and astronomer Camille Flammarion’s 1894 novel Omega: The Last Days of the Earth (La Fin du Monde). The film follows sisters Dina and Edith West (Ebba Thomsen and Johanne Fritz-Pedersen), who, through their choices in husbands and futures, seal their fates as the sky comes falling down in the shape of a comet brushing past the Earth. The first elopes from her working class fiancé with a handsome and rich mine owner (European superstar Olaf Fønss). Edith marries a poor but morally upstanding sailor. The coming of the meteor sends the world into panic. Manipulating public fear and the press, Dina’s shrewd husband makes a killing on the stock market, while he and other millionaires prepare to sit out the coming disaster in a luxurious bunker. But Dina’s ex-boyfriend now leads the workers, who in a fit of communist rage descend on the bunker, insisting on equality in catastrophe. Meanwhile, hard-working Edith finds her husband away on the seven seas when disaster strikes. Her house and village are drowned in a flood, but as though through divine intervention, she is saved from her rooftop by a passing vicar in a row boat, who takes her to a nearby church, where she dutifully awaits the return of her husband, hoping against hope that they might start a world anew.

It’s an epic of biblical proportions, beautifully directed by August Blom, the father of Danish cinema, in starkly contrasted black and white. For their time, the special effects, complete with the flooding of a house and fire raining from the sky over a superbly crafted miniature village, are hugely impressive. The final panorama showing Edith waiting on the shoreline, the famous “Buried Church” behind her, is breathtaking. Sure, the characters are broad stereotypes, representing ideas rather than people, and the “blessed are the meek” conclusion to the clash of ideologies in Europe at the period feels somewhat simplistic. But as a visual piece of epic storytelling, The End of the World is magnificent. Full review.

A restored version of the film is available for free streaming with English intertitles on stumfilm.dk, and as a box set together with A Trip to Mars on DVD by the Danish Film Institute.

10. A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Of course this had to be in the Top 10. Admittedly, this 120-year-old, 12-minute-long trick film is crude and simple by modern standards. In the early days of cinema, most filmmakers were technicians or documentarists. Then along came Georges Méliès, an illusionist, a showman, an artist, actor and director on stage and director of the legendary Theatre Robert-Houdine. While pioneers like the Lumière brothers dispatched their cameramen around the world for ethnographic documentation, Méliès started creating little stories on film, first on his theatre stage, and then in his purpose-built, glass-roofed Star Film studio, the largest in the world at the time. Drawing on the so-called fairy plays popular in Paris, he started creating elaborate, often mechanical, sets for his movies, started telling short stories, then longer, up to six or eight minutes. In 1899 he gained international fame with his retelling of Cinderella, and later Bluebeard and Jack and the Beanstalk. But the film he would forever be remembered for was A Trip to the Moon or Le Voyage dans la lune. Inspired both by Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and H.G. Wells’ First Men in the Moon, it tells a fairly simple story.

A scientist proposes a trip to the moon, and spends a good time arguing with other scientists. Then a rocket is built, and gets a grand sendoff as it is shot from a great cannon. It lands on the moon, hitting the man in the moon square in the eye. The travellers find an underground civilisation of Selenites, whom they try to fight off with their umbrellas. Upon contact, the insectoid moon-men explode in a puff of coloured smoke. Eventually they are brought before the moon king, whom they insult, escape and return to the Earth with a Selenite that they parade across the streets. Compared to the elaborate effects of Méliès’ later films, A Trip to the Moon is a rather simple exercise, but for 1902 it was revolutionary. At 12 minutes it was longer than most films, it was the most expensive movie ever made, with a cast of several dozen and with numerous meticulously crafted sets. It was the first movie to show another world, and the first real science fiction film. Such was its success that it spread like wildfire over the world, and a small industry of creating pirated copies of the movie sprung up in the US. So many illegal copies were in swing that Méliès sent his brother to New Jersey to open up a Star Film office just to deal with the piracy problem. It is an innocent fairy-tale, imbued with a passion of storytelling, of entertaining, of lifting our spirits by, for a few brief moments, spiriting us away to a world of magic and wonder. Full review.

Just Google it.

9. A Trip to Mars (1918)

Born at the tail end of WWI, this Danish 1918 silent epic came out of four years of devastating war, a war that few ordinary people could see any reason or purpose for. A Trip to Mars, or Himmelskibet (“heaven ship”) was a direct commission by Nordisk Film’s co-founder Ole Olsen as a pacifist plea for humankind. Denmark’s movie industry was not as dominant as it had once been, but still one of the major movie exporters of the world. The script was co-written by Olsen and Danish poet and author Sophus Michaelis and the movie was directed by Holger-Madsen. Although not as well remembered today as August Blom or Benjamin Christensen, Holger-Madsen was, along with these two, one of Denmark’s three most important directors between 1913 and 1920. Scientist and pilot Avanti Planetaros (Gunnar Tolnæs) leads a crew of intrepid explorers on a daring trip in a space dirigible to Mars, where they discover and Ancient Greek-inspired society. After learning the Martians are vegetarians, one of the crewmembers shoot a goose from the sky. This, he finds, is a terrible crime, as all life is sacred on Mars. Trying to avoid capture, the barbaric humans pull out there guns and even a grenade, that fatally harms a young Nils Asther, before the Swedish actor even has had a chance to embark on his career as a Hollywood heart-throb. Planetarios manages to calm his crew, and have them accept their sentence in The House of Judgement. This house turns out to be something resembling a movie theatre, where the Earth crew watch a film on how Martians became pacifists. Enlightened, Planetarios falls in love with a Princess of Mars (Lilly Jacobsson), who seduces him in a wonderfully rendered psychedelic forest.

A Trip to Mars is a film typical of Holger-Madsen, an idealist filmmakers described by his contemporaries as impulsive and “frail”. He made the film Ner med vaapnen in 1914, a pacifist movie based on the writings of Bertha Suttner, but this did not sit well in the early days of the war, and was banned in Germany. Another cry for peace was Pax Aetherna or Peace on Earth (1917), sometimes described as the world’s first anti-war film. A Trip to Mars was a natural conclusion to his peace triptych. The movie is both naive and crude by modern standards, but it is an important movie for SF, inasmuch as it is the first feature film to describe, with some degree of science, a trip to another planet. While the propeller-driven dirigible isn’t particularly convincing, the film’s description of life inside the spaceship is more akin to Alien than any film that came before. It is unusual for showing the boredom of a long trip, personal tensions rising, and it conveys the feeling of claustrophobia besetting the crewmembers well. The Martians in their strange toga-like garments and silly headgear are hard to take seriously, and Mars does seem rather bare of structures and infrastructure considering the race’s high level of civilisation. But there’s a wonderfully poetical feel about many of the sequences on Mars, hightened by Holger-Madsen’s keen eye for lighting and composition. A product of its time, this one is highly entertaining if watched with its context in mind. Full review

A restored version of the film is available for free streaming with English intertitles on stumfilm.dk, and as a box set together with The End of the World on DVD by the Danish Film Institute.

8. Cosmic Voyage (1936)

The best science fiction movie to come out of Europe in the 30’s is the Soviet classic Космический рейс (Kosmicheskiy reis) or Cosmic Voyage, sometimes translated as The Space Voyage, from 1936. The film is nominally inspired the novel Beyond the Planet Earth by the grandfather of space exploration, rocket scientist and author Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. In all actuality, it is an original script loosely inspired by the ideas in the book, written by Tsiolkovsky himself and Aleksandr Filimonov. It follows elderly rogue scientist Sedikh (screen legend Sergei Komarov), modelled on Tsiolkovsky, 10-year-old upstart Andrei (Vassili Gaponenko) and a young female professor called Marina (I never catch her last name), played by Ksenia Moskalenko, eerily resembling of Brigitte Helm. After a canine test cosmonaut returns dead from an orbital flight, the director of Moscow’s space institute grounds professor Sedhik, the designer of the first moon rocket, fearing he is too old and frail to undertake the pioneering first moon voyage. But thanks to the inventiveness of young Andryusha, our heroic trio manage to sneak onto the space rocket “Stalin” (what else?) in the middle of the night — and blast off for the new frontier. They experience the obligatory botched landing, rupturing an oxygen tank, and to make matters worse, Sedikh manages to land on the far side of the moon, out of radio contact. However, after some thrilling adventures in the lunar landscape, the pioneer spirit of these intrepid explorers manage to return home, ushering in a new era, for the betterment of mankind and the glory of the Soviet Republic.

Despite the namedropping of the USSR’s Great Dictator and a bit of flag-waving in the end, this film, directed by Vasili Zhuravlyov, is refreshingly free from stodgy propaganda. At heart it is a fun juvenile adventure movie, aimed directly at the young would-be space pioneers of the future. The edutainment angle is there, but never overbearing. When Hollywood was still avoiding SF like the plague, national movie company Mosfilm splashed out on a costly, impressive space adventure, no doubt inspired by Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon from 1929. The special effects are ambitious, utilising ground-breaking wirework for zero-gravity conditions and long stretches of stop-motion animation for the low-gravity sequences on te moon, even though they are not always entirely convincing. miniatures are all first class, as are the designs for both the moon and the spacecraft. The script is well written: the adventure is exciting and both the flight and the moon scenes carry with them a sense of awe and wonder. There is a good deal of humour, and it is actually funny. Despite being made in 1936, this is a silent films, as were most movies intended for wide distribution in the Soviet union at the time, since most of the country’s movie theatres had not yet been adapted for sound. Full review.

A restored version of the film with English intertitles is available on sovietmoviesonline.com, and for free on Youtube. It has also been released as an Editions Filmmuseum DVD.

7. Our Heavenly Bodies (1925)

Wunder der Schöpfung, or Our Heavenly Bodies, is the most neglected SF masterpiece of the silent era – partly, one suspects, because it is an edutainment movie rather than a straight fictional story. What makes it so astounding is not only its immense scope – in its running time of 90 minutes it not only incorporates the entire history of our planet – from its birth, the formation of life, and its eventual destruction. It also gives us a basic introductory lesson in astronomy, evolution and the natural sciences. In between illustrated lectures it sets out into the speculative void – fictional segments take us out into space in a spaceship, with which we visit the moon and the planets in our solar system. Setting foot on these strange celestial bodies alongside the astronauts of the film, we experience the shifts in gravitation, gaze out over the wondrous, otherworldly landscapes, and even meet the hypothetical inhabitants that might live on these planets. In essence, this is Carl Sagan’s TV show Cosmos, only condensed into an hour and a half. No, what makes this film so extraordinary are the visuals. Drawing from the same art deco influences as the design team on Metropolis, the film shows us impressive futuristic landscapes and director Hanns Walter Kornblum uses nifty practical effects to portray weightlessness in space – effects that were noted by Stanley Kubrick, who re-created them in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film is basically a 90-minute special effects reel, using every trick known to filmmakers at the time: stop-motion animation, claymation, black screen replacement shots, double exposure shots, rod puppets, stop-trick photography, traditional animation and forced perspective photography. Most impressive is the miniature photography showing the entire solar system, each planet and moon, in motion around the sun. These effects were made with the help of six cinematographers and nine animators. Of course, it’s crude by today’s standards, and the science is naturally off a bit since our understanding of space and the universe has broadened. But as a visual journey it is eclipsed by few, if any, films of the silent era. Full review.

Available on Youtube with German intertitles, and as an Editions Filmmuseum DVD with English ditto.

6. Homunculus (1916)

A roaring success in Germany and other parts of Europe upon its release, and all but forgotten today, Homunculus is a classic example of the German ambition when it came to filmmaking in the 1910’s. In the US, a “film serial” generally meant 20-minute western or crime shorts where a daring gal chased a criminal mastermind. In Germany a “film serial” could mean three two-hour films depicting the country’s Medieval legends or, as in this case, six one-hour films following the doomed existence of an artificial man with superhuman powers but without a soul.

Robert Reinert’s multi-layered script draws on Frankenstein and Faust, as well as Freud, Nietzsche and Marx to create both a treatise on the human condition as well as a comment on WWI. While scarcely shown outside Germany before 1920, it turned Danish lead actor Olaf Fønss into a matinée idol and even influenced fashion. Homunculus uses his origin as an artificial creation, in essence a perceived paternal betrayal, as an excuse for his own evilness. He reasons that because he cannot feel love, he must be evil, and as he is evil, he is not morally responsible for the evil that he does. Fønss is magnetic in his portrayal of Homunculus, pulling out all the stops for a wonderfully charismatic and over-the-top performance. Homunculus is larger than life.

For decades only pieces of the film were available, until the 1920 version of the serial was re-edited and restored from various prints by film historian Stefan Drössler in 2014. Apparently, the process of restoring the film is still on-going, and as Drössler has lacked the money for a high-end digital restoration, the film has not been released for home viewing, although it has been screened from time to time. There is an 80-minute condensation of the film with Italian intertitles floating around on Youtube. Actually, I’m not sure that 120 minutes are really missing, as the story is basically all there, with a few minor omissions. My guess is that the Italian print has been digitised at the wrong frame rate, cutting over one third of the running time. Full review

Available as a truncated version with Italian intertitles on Youtube (and with English intertitles as bootleg DVD).

5. Miss Mend (1926)

At spot #5 it’s yet another film serial! Today it is what we would call a mini-series, consisting of three one-hour episodes. And once again, it is one that you might be forgiven for having never heard of. Perhaps the best of all American-styled action serials of the silent era, this international spy-fi yarn is a breezy, action-packed, impeccably filmed and fun tour-de-force. And if you figure Miss Mend (1926) is a bit of an odd title for a US film serial, then you are quite right: it was made in the Soviet Union and is actually spelled Мисс Менд. The film follows the plucky American clerk Miss Mend (a superb Natalya Glan) and her two reporter friends as they travel from the US to the USSR in order to uncover a diabolical terrorist plan involving the release of nerve gas on the entire US population — and blaming the communists for it.

Miss Mend was part of a push during the relatively liberal NEP era during the 20s in the USSR, when part of the communist intelligentsia worried about the lack of exciting escapist literature for Russian children and youths, making many turn to Western, often anti-communist, adventure and detective novels and comics. This gave birth to the so-called “Red Pinkterton”: Western-style detective and action novels with socialist underpinnings. Author Marietta Shaginyan was one of the most prolific writers of Red Pinkertons, including the 1924 story Mess-Mend: Yankees in Petrograd, on which the film is based. Co-directed by two of the Soviet Union’s most interesting director, Fyodor Otsep and Boris Barnet, Miss Mend is a fast-paced, spunky, fun and well-acted spy-fi serial. Full review

A restored version w English subs is available for streaming on Mubi & Kanopy and as a Flicker Alley DVD.

4. Aelita, Queen of Mars (1924)

Just pushed out of the Top 3 is another Soviet production, the satirical classic Aelita. As legendary as it is misunderstood, Aelita is especially well remembered for its beautiful, modernist, constructivist designs by Viktor Simov, Isak Rabinovich and Alexandra Exter. The visuals of Aelita had a huge impact on the look of Metropolis and helped define what an alien society would look like — an influence still visible today. The story sees three reluctant comrades, a love-sick dreamer and inventor, a retired revolutionary soldier and a petty police detective, embark on a mission to Mars, where they plot to overthrow its despotic rulers through a worker revolt. In this they are aided by the princess Aelita (not a queen as the English addendum to the title suggests), who nevertheless reasserts herself as sole ruler after the revolution, thus betraying the cause. It is easy here to draw parallels to the dualistic character of Maria/Maschinenmensch in Metropolis.

The film is loosely based on the 1923 novel with the same name by Alexei Tolstoi, but there is little similarity between book and film, other than the most broad strokes. Tolstoi’s novel is a space adventure in the vein of Edgar Rice Burroughs, with socialist underpinnings. The film, however, is to a large extent Earth-bound, as it follows our three protagonists, and more importantly, their wives, who are left behind to rebuild the country after the revolutionary war. Modern viewers often write off the movie as heavy-handed Soviet propaganda — and it does contain a good amount of communist chest-beating. But it is not the communist revolution on Mars that the film celebrates, but the slow drudge of women at home, making do in the post-revolutionary scarcity and rationing. A surprising amount of the plot is concerned with things like shopping, cooking, cleaning and rationing — ordinary people working together to slowly make a better future for themselves and the people. The “heroes” of the film are juxtaposed against this background as irresponsible action junkies. Neither the dreamer nor the soldier have any patience for the dreary, unromantic work of making a better world, but instead leave their kin behind for a scatter-brained adventure in the name of galactic revolution. Rather than a mindless propaganda film extolling the virtues of international communism, Aelita is a biting satire of revolutionary romanticism. And if you don’t believe me, just ask the Soviet censors who quickly withdrew the movie from cinemas, keeping it banned until the 70’s. Full review

Available on Youtube, archive.com and as several DVD releases, including a 2015 Flicker Alley release.

3. Woman in the Moon (1929)

Our Top 3 begins with a German classic from 1929, Woman in the Moon, or Frau im Mond. Considered one of demon director Fritz Lang’s minor films, it still casts a giant shadow over the genre of science fiction. Frau im Mond was the first movie to envision a scientifically feasible voyage to the moon, and it did so with the help of several of Germany’s top rocket scientists, which also happened to be the world’s top rocket scientists. Germany in the twenties had rocket fever, and several of the experts involved in the film would later become crucial for the founding of NASA and the first moon voyage in 1969. The movie set the technical and artistic standards for all space voyage films to come, and many of the tropes it pioneered are with us to this very day. Let’s check them off. A ridiculed scientist proves everyone wrong by building a rocket to the moon. Check. Personal tensions and sabotage plague the preparations for take-off. Check. Foreign spies try to steal the rocket secrets. Check. A beautiful female scientist, an elderly pioneer and a handsome man take off in space. Check. A kid stows away. Check. Countdown to take-off. Check. G-forces cause problems because no-one thought to put the brake in reach of the bunk. Check. Free-floating alcohol bubbles in zero gravity. Check. (Why is whisky always considered essential on these trips?) A crew member falls ill/is a saboteur/goes wacko. Check. A botched landing leads to a lack of air/fuel for the return trip, so someone has to stay behind on the moon. Check. I could go on, but you get the point.

Much of the film is actually Earth-bound, and deals with the planning and the preparations of the moon voyage, as well as a convoluted spy plot. At over two hours in length, the film is considered by some to be too long for its own good, but for friends of a good spy yarn and for all cineastes, the lead-up to the advertised moon voyage is even better than the climax. The story is immaculately laid out and Lang, clearly in a playful mood, tells so much in just simple images that there is really no need for dialogue. The mis-en-scene, the framing, the reveals, the editing, all tell stories of their own. Lang shows here why he was considered the master of the silent film. The actual moon voyage is less exciting for a modern viewer, as the tropes the movie created are so clichéd today. The ending also careens into all-out comic book territory. Nevertheless, Woman in the Moon is a fantastic movie, even more so considering how hugely influential it has been. Full review.

The film is in the public domain and available at least at archive.org, but has few commercial streaming alternatives. Kino Lorber’s digital restoration is available both as DVD and Blu-ray.

2. The Hands of Orlac (1924)

This pick will no doubt meet with criticism. But at #2 we have the Austrian 1924 silent film Orlacs Hände, or The Hands of Orlac. To a lot of readers, the film’s American 1935 remake Mad Love, starring Peter Lorre and Colin Clive will likely be more familiar. But the original is a rawer, grittier, sweatier danse macabre, directed by Robert Wiene, the mastermind behind the epoch-making The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), and featuring its spellbinding star Conrad Veidt in what may well be his most intense on-screen appearance. Based on French SF and body horror pioneer Maurice Renard’s 1920 novel Les Mains d’Orlac, the film follows famous piano virtuoso Paul Orlac, who loses his hands in a railway accident. In an experimental surgery, he is given a hand transplant — the “donor” is the notorious murderer Vasseur who has just been put to death by hanging. Orlac becomes obsessed by his new hands, believing that the spirit of the murderer lives on in them, slowly taking control of him. He feels alienated from his own hands, unable to caress his wife, as if he would be defiling her with the hands of a murderer. He has violent hallucinations, and at night starts re-enacting Vasseur’s killings with a knife. When a money-lender is killed with the knife used by Vasseur, he is convinced that it is he that has committed a crime, spurred on by a mysterious man fanning his self-doubt and self-loathing. Soon, Orlac in his despair is ready to face execution for a murder he has no recollection of having committed.

Written in an era of great advances in medicine as well as during the period of the birth of psychology as a science, the novel explored themes of identity and of the soul very much in the spotlight of academic debate. This was an era in which experiments were starting to be made in the fields of artificial insemination, begging questions of the actual location location and origin of the soul. Could someone born without natural intercourse have a soul — and more pertinent for the novel: did someone’s soul reside in all of the body, and to which extent did it linger after death. The style of German Expressionism that arose on the early 1920’s was partly born out of an economic necessity: when filmmakers found themselves without resources for realistic sets, they started creating unrealistic sets — symbols of rooms and streets. But it was also an expression (pardon) of the expressionist movement: the make the surface of the art express what is within. And for many Germans directly after WWI, what was within was: horror. Horror, confusion, guilt, a sense of unreality, as a nation was struggling to come to terms with the atrocities of the war. The Hands of Orlac is one of the finest examples of German Expressionism, largely thanks to the magnificent acting feat of Contad Veidt. Veidt is on screen for almost every minute of the two-hour movie, portraying his character spiralling ever deeper into hysteria and insanity. For an audience not used to silent films, Veidt’s performance must be befuddling. It’s not so much traditional acting as it is a “visceral dance”, as critic Alfred Eaker puts it. It is an awesome acting challenge to make something like your own hands seem completely alien to yourself, as if it is some dark menace stalking you, something you would like to hack off and get as far away from as you could. But there they are, every waking moment, and they even haunt you in your dreams. I think enough isn’t said about the deep wells of emotion that Veidt draws on in his roles. In his very best roles, like the Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Orlac and Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs (1928), he inhabits an aching sadness and a touching fragility. His emotions are always there, plainly on his skin for all to see, which makes it possible for him to pull of the feat of acting in a highly exaggerated and expressive manner, without ever seeming to overact.

The film isn’t without its flaws. For one thing, at 112 minutes, it’s at least 20 minutes too long. The commonly available version, restored in 2013, is the original pre-release cut. The German theatrical cut was actually only 93 minutes long, because of cuts demanded by censors. The ending, although true to the novel, is also a bit of a disappointment, sort of pulling the rug from under the feet of the story. It’s a clever twist, and a psychologically interesting one, but one that will upset SF and horror fans. Full review.

The film is in the public domain and available at least at archive.org, but has few commercial streaming alternatives. The theatrical version is available as a Kino International DVD and the restored 112-minute version as an Eureka Blu-ray.

1. Metropolis (1927)

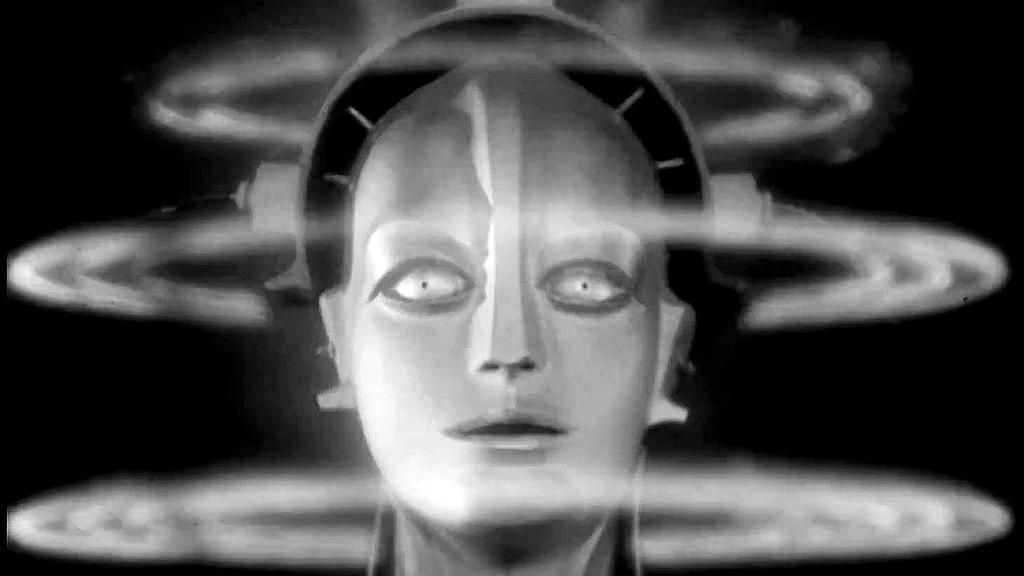

Yes, the film at our #1 spot is so expected that it is a bit of a boring choice. But there really is no alternative. Few films have shaped cinema in the way this 1927 German classic has done. Metropolis’ designs are part of our cultural heritage, and continue to influence movies, theatre, video games, art and architecture to this very day. From the majestic art deco buildings to the nightmarish underground city in which the film’s workers toil, from the frenzied night club scene in which a half-naked Brigitte Helm enchants the upper class men to follow her to their doom, to the image of the mad scientist Rotwang in his proto-Frankenstein laboratory. Not to mention the legendary design of the robot, Maschinenmensch, completely changing the way we seen robots today, its influence still in the designs of C-3PO, Robocop, Iron Man’s mechanical suit and in Ultron, as well as hundreds of copies, homages and ripoffs.

H.G. Wells famously called Metropolis “the silliest of films” after its British premiere, and even its director, the notorious Fritz Lang, disowned it because of his ex-wife Thea von Harbou’s “politically naive” script. In its somewhat clunky ending, the class conflict that nearly tore the city apart is resolved through the notion that the “hands and the brains must be guided by the heart”, or simply put “why can’t we all be friends?” For a film that spends two and a half hours working up an elaborate, operatic plot concerned with the evils of capitalism and the class divide, this does feel like an apologetic sort of wishful thinking, and it’s no surprise that socialists like Wells sighed in frustration (as did apparently Lang himself). In its original 150-minute grandeur (although seldom screened this way after its German premiere) it is also too long and its plot too convoluted, at least for someone sitting down for a casual Saturday morning viewing. But if you’re in the right state of mind, Metropolis is two and a half hours of glorious cinema. The world’s most expensive film by far when it was made, it took full advantage of UFA’s newly built studios at Babelsberg. The sets are magnificent, the artwork stunning and the special effects still hold up seamlessly today. The film contains some of the best matte work done before the advent of computer graphics and the movie’s use of the so-called Schüfftan process, in which live actors were dropped into miniature sets through a mirror technique must have seemed like magic at the time. To this very day, viewers scratch their heads over the effects in the scene where the robot is transformed into Maria — how was it done?! This is a film in which there is not a blink of an eye, not a wayward gesture, that was not approved and planned by the director. Fritz Lang infamously pushed his actors to exhaustion. The actors involved unanimously described the experience as a nightmare. Best known is the scene where Lang had Brigitte Helm and hundreds of poor children standing for days on end in water that he deliberately kept at a low temperature. He insisted on using real fire for the burning of the fake Maria at the stake – causing Helm’s helms to catch fire. A simple shot of male lead Gustav Fröhlig collapsing at Maria’s feet took two days to film. 18-year old debutante Brigitte Helm spent day after day in the extremely uncomfortable robot suit which was hot, chafed and designed so she couldn’t sit down. She pointed out to Lang that she could alternate with a stunt double, as nobody in the audience would know if it was her or somebody else in the suit. Lang replied: “I would know”. We are in no way condoning the mistreatment of actors or crew, but there is no denying the the result, in this case, is magnificent.

As a conventional movie plot, the script has its flaws, but this is not a conventional film: it is a silent opera, using images instead of music to create an all-immersive experience. The stars of the movie, Brigitte Helm, Gustav Fröhlig and Rudolf Klein-Rogge are fine-tuned instruments against the symphonic background of the designs and effects and the thousands of extras are the choir adding to the majesty of the performance. Few attempts were made in the years to come to replicate the vision of Metropolis, and those that did all ultimately failed. Even today, with blockbuster budgets bloated to over ten times the equivalent of 5 million Reichsmark in 1927, few can match the epic scale of Metropolis. Full review.

The film is in the public domain and a restored Kino Lorber version is available for free on archive.org, Youtube and a string of commercial streaming platforms, as well as on DVD and Blu-ray.

Janne Wass

Please note that many of the films on this list may be available for (legal) streaming only in the US. I have heard it rumoured that many hard-to-find movies can be watched at the Russian video streaming service ok.ru, but of course I would never recommend bypassing copyright laws by searching for them there.

Leave a comment